Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationships between physical, psychological, and social factors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and disability in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

A sample of 106 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) completed measures of self-reported disease activity and psychosocial functioning, including coping, personal mastery, social network, perceived stress, illness beliefs, the SF-36 and Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI). In addition, physician-based assessment of disease activity using the Disease Activity Scale (DAS 28) was obtained. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationships between psychosocial factors and scores on the SF-36 and HAQ-DI.

Results

Lower self-reported disease activity and higher active coping were significantly related to SF-36 physical functioning scores, whereas lower self-reported disease activity, higher personal mastery, and lower perceived stress contributed to higher SF-36 mental health functioning. Higher self-reported disease activity and lower helplessness were associated with greater disability as indexed by the HAQ-DI. The DAS 28 was unrelated to these outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings highlight the importance of targeting psychological factors to enhance HRQOL in the clinical management of RA patients.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, psychological factors, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory disease that can lead to disability and significantly interfere with functional adaptation [1,2]. Symptoms such as joint pain, swelling, and fatigue are disease-specific stressors that tax the adaptive resources of patients and heighten the risk for patient reported declines in function (i.e., difficulties in carrying out activities of daily living) as well as reports of emotional disturbance [3] which together create enormous psychological and financial loss for those afflicted [4].

Given the salience of such subjective reports of declines in patients’ physical, social, and psychological functioning, there is growing interest in using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to assess treatment effectiveness [5]. PROs represent a patient's evaluation of his/her unique health status distinct from the evaluations of physicians and laboratory findings, and have a long history of use in the measurement of outcomes such as psychological distress, pain, and depression in patients with RA. Increasingly, PROs are being adopted as a mechanism for evaluating clinical efficacy in randomized clinical trials [6,7] to allow for an analysis of whether treatments that are designed to reduce disease activity, for example, will also improve clinical functioning from the patient's perspective.

An important measure of PROs is health-related quality of life (HRQOL). While various definitions have been proposed, HRQOL generally refers to the ways in which a given health condition affects a patient's physical ability and capacity to function in a variety of social and emotional roles. HRQOL, which may be generic or disease-specific, is generally divided into measures of physical functioning and emotional well-being [8]. In contrast to disability measures, which assess how health limits a patient's ability to perform specific tasks, HRQOL is a more global construct that indicates how well a patient is doing given the totality of his/her medical condition. Hence, the determinants of disability and HRQOL are likely to differ, as they are distinct constructs tapping different facets of functioning.

A key issue in HRQOL research in RA concerns the identification of variables, along with disease activity, that play prominent roles in explaining physical and mental health functioning. A common observation among rheumatologists is that significant variability in health functioning exists among RA patients who have similar levels of disease activity and joint damage [1,9], raising the question of what factors are responsible for these functional differences. In fact, research has demonstrated that disease activity and inflammation in RA correlate only modestly with HRQOL and other psychosocial measures [10,11]. The same pattern has been found in other rheumatic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus [12].

At this juncture, research has not adequately addressed the variables contributing to HRQOL in RA. Indeed, while studies have demonstrated that variables such as illness beliefs, coping, and social support are correlated with pain and psychosocial adjustment in RA patients [13,14,15], the contribution of such factors to HRQOL has not been adequately determined. This research adopted a biopsychosocial framework [16] to evaluate the role of psychosocial and biomedical factors, in understanding patient variability in functional outcomes. Previous research has not explicitly adopted this approach in conceptualizing the variables affecting HRQOL in RA. This study evaluated this framework for HRQOL and disability in a sample of patients with RA in the greater metropolitan Los Angeles area.

Materials and methods

Patient Recruitment

Patients were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers and flyers posted in clinic offices in the Departments of Rheumatology at UCLA and Cedars Sinai Medical Center (CSMS), Los Angeles. After a brief telephone screening conducted by the project coordinator at UCLA, patients were referred to CSMS to determine medical eligibility. The study rheumatologist (MW) conducted a diagnostic evaluation that included assessments of tender and swollen joints and disease activity using the DAS 28 to confirm a diagnosis of RA. Eligible participants were required to: (1) be 18 years of age or older, (2) meet American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised criteria for RA, (3) be on a stable disease-modifying drug regimen for three months prior to study entry, with no change in drug dosage for at least three months prior to study entry, (4) have a stable disease course for three months (no major changes requiring medication changes or administration of injected or pulse corticosteroids), (5) be free of serious co-morbid medical conditions such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, renal failure, or cancer that would confound interpretations of health status, and (6) not pregnant. Patients meeting these eligibility criteria were referred to UCLA for an evaluation of psychiatric status, physical functioning, and psychosocial adjustment. The project coordinator administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) [17]. SCID diagnoses were made in a consensus meeting with the principal investigator (PN), co-investigator (JP), and project psychiatrist (MI) with attention to criterion validity. Patients who had a serious psychiatric condition such as bipolar disorder, psychosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder or who were at risk for suicide were ineligible to participate in the study.

Data Collection

The psychosocial component of the evaluation consisted of paper and pencil assessments of: illness beliefs, pain coping, perceived stress, personal mastery, and social network/support. Participants also completed self-report measures of disease activity, health-related quality of life, and disability.

Medication Use

Reports of current medication use were collected for each of the following categories: analgesics/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, biologic agents, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and “other” (drugs for other medical conditions, including psychotropics).

Psychosocial Measures

Illness Beliefs

The 5-item Helplessness and 7-item Internality Subscales of the Arthritis Helplessness Index (AHI) [14,18] were used to measure patients’ beliefs about ability to manage RA.. The Helplessness subscale reflects a perceived inability to control RA symptomatology (e.g., pain) and disease course (e.g., “arthritis is controlling my life”) while the Internality measures perceived control over RA (“managing arthritis is my own responsibility”).

Pain Coping

The Pain Management Inventory (PMI), developed by Brown and Nicassio [15], was used to measure the degree to which patients reported either active (e.g., functioning in spite of pain) or passive (e.g., lying down) coping strategies when pain from RA reached a moderate or greater level of intensity.

Perceived Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) is a 10-item scale [19] that measures the degree to which participants find their lives to be unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming. The PSS assesses the cognitive and emotional burden of feeling stressed rather than events that may lead to stress.

Personal Mastery

The Personal Mastery Scale (PMS), a 7-item scale developed by Pearlin [20], was used to assess the construct of personal mastery - the degree to which individuals believe they can exercise control over important forces affecting their lives.

Social Network

The Berkman & Syme Social Network Index (SNI) [20] was used to assess patients’ social networks. The SNI calculates network size based on the interaction one has with a spouse, relatives, close friends, group activities, and participation in religious meetings or services. The method described in Loucks et al. [21] was adopted in which the following categories were scored; married (no=0; yes=1); close friends and relatives (0-2 friends and 0-2 relatives=0; all other scores=1); group participation (no=0;yes=1); participation in religious meetings or services (<every few months=0; once or twice a month=1). Scores in the sample ranged from 0 to 4, indicating increasing network size.

Disease Activity

Disease activity was evaluated using two measures, the DAS28 [22] and the Rapid Assessment of Disease Activity in Rheumatology (RADAR) [23]. The DAS28 is a physician-based measure comprised of the following indices that are aggregated to form a summary score: tender and swollen joint counts (0 to 28), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and patient global score (0 to 100). The RADAR was used to measure self-reported measure disease activity. The RADAR consists of questions about past and current disease activity, pain, morning stiffness, and the degree of pain/tenderness in 10 joints on the right and left sides of the body. In previous research, the RADAR has been shown to be an efficient, valid proxy for physician assessments of disease activity and joint pain [24,25].

HRQOL

The SF-36 [8] evaluated generic HRQOL. The measure consists of 36 items tapping eight components of well-being: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and emotional well-being. A scoring algorithm was used to aggregate the eight components into physical and mental health summary scores.

Disability

The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) [26] was used to evaluate RA disability. The HAQ-DI is a validated self-report instrument that assesses the difficulty of completing tasks in 8 categories — dressing, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and usual activities. Extensive research on the validity of the HAQ-DI and its use in clinical and research settings has been accumulated over the last 30 years [27].

Statistical Approach: Tests of the Model

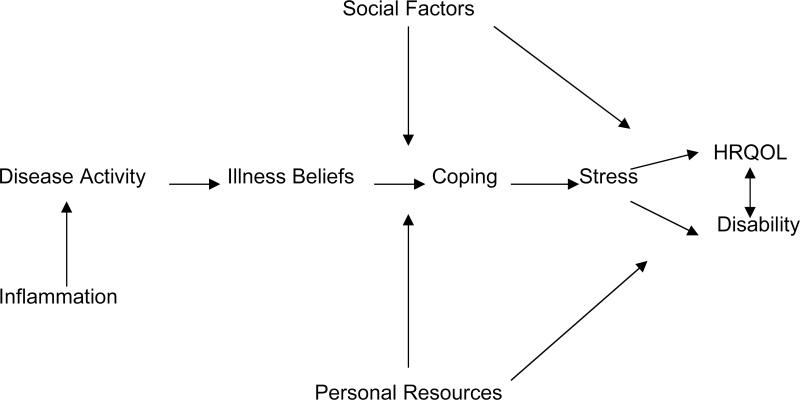

We used the model depicted in Figure 1 to test the contribution of disease activity, psychological, and social factors to HRQOL and disability in RA. Key assumptions of the model are the following: (1) disease activity, social factors (e.g., social network), and personal resources (e.g., personal mastery) have independent, additive effects on HRQOL and disability; (2) the coping process, comprised of variables such as helplessness, pain coping, and perceived stress, affects outcomes directly and serves as a mediator of the effects of disease activity on HRQOL and disability; (3) social factors and personal resources affect HRQOL and disability directly or indirectly by affecting elements of the coping process; (4) the model is dynamic over time in that the coping process, HRQOL, and disability may potentially affect changes in disease activity over time, although this hypothesis was not evaluated in the present cross-sectional analysis. Hence, the contributions of the first three components of the model were primarily tested. Using hierarchical multiple regression analysis, independent variables were entered sequentially into the regression equation, allowing for a test of each block of variables while controlling for the presence of all other variables entered on preceding steps. For HRQOL physical and mental health summary scores and HAQ-DI, variables were entered sequentially into the regression equation in the following order: (1) medication use, (2) disease activity (RADAR, DAS 28), (3) social network size and personal mastery, and (4) coping process variables - helplessness, internality, active coping, passive coping, and perceived stress. This process depicts the manner in which patients’ perceptions of control over disease (helplessness/internality) can affect mode of coping (active/passive) which, in turn, can result in perceptions of stress. Mean substitution was used to estimate missing data for some variables.

Figure I.

Model Describing the Contribution of Biological, Psychological, and Social Factors to HRQOL and Disability in RA

Results

Sample Characteristics

There were 106 predominantly female (83%) participants with an average age of 56.2 years and an average of 16.0 years of education. The majority of participants (52.8%) were Caucasian, with 10.4% African-American, 14.1% Hispanic, and 22.6% of “other” ethnic descent. Average disease duration was 12.00 years (sd=11.4). DAS28 scores reflected moderate disease activity (m=4.3, sd=0.1). SF-36 summary scores indicated substantial difficulty with physical functioning (m=33.2, sd=7.9). Levels of helplessness, passive coping, and active coping approximated findings from other RA samples [14.15]. Scores on internality and personal mastery reflected considerable perceived control over RA and other life skills, respectively (see Table 1). Participants reported social networks of modest size (m=1.8, sd=1.1).

Table I.

Participant and Variable Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Total N=106 | (Min-Max) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||

| Age | 56.22±12.45 | (22-79) |

| Years of Education | 15.96±2.39 | (12-21) |

| Yearly Median income ($) by zip | 51,142±18,631 | (17,644-121,527) |

| Years with RA | 11.97±11.40 | (<1-53) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 56(52.8%) | |

| African American | 11(10.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 15(14.1%) | |

| Other | 24(22.6%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 88 (83%) | |

| Male | 18 (17%) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 47 (44.3%) | |

| Not Married | 47 (44.3%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 12 (11.4%) | |

| Model Variables | ||

| SF-36 Physical Functioning Composite | 33.19±7.92 | (15-47) |

| SF-36 Mental Health Composite | 55.21±10.51 | (21-70) |

| Disability (HAQ-DI) | .84±.60 | (0-2.38) |

| Disease Activity (RADAR) | 11.45±9.34 | (0-36) |

| Disease Activity (DAS-28) | 4.32±.95 | (1.68-7.32) |

| Personal Mastery (PMS) | 23.58±3.46 | (13-28) |

| Social Network (SNI) | 1.75±1.13 | (0-4) |

| Active coping (VPMI) | 22.77±4.73 | (12-35) |

| Passive coping (VPMI) | 24.84±6.99 | (12-43) |

| Helplessness (AHI) | 14.75±3.93 | (7-28) |

| Internality (AHI) | 30.25±5.93 | (7-42) |

| Perceived Stress (PSS) | 11.35±6.90 | (0-36) |

Multiple Regression Results

Physical Functioning. Medication use at step 1 did not contribute to physical functioning; however, at step 2, the entry of disease activity was significant, accounting for 10% of the variance in physical functioning. Higher RADAR scores, reflecting greater disease activity, were associated with poorer physical functioning (be=-.29, p<.01), while the relationship between physical functioning and DAS 28 scores was not significant. At step 3, social network and personal mastery did not contribute variance to physical functioning, but at the final step, coping process variables were highly significant, uniquely explaining 17% of the variance. Active coping was associated with better physical functioning (p<.05), whereas worse physical functioning tended to be associated with higher passive coping (p<.10) and higher helplessness (p<.10), although these relationships did not reach statistical significance. Internality and perceived stress were not related to physical functioning scores. The model as a whole accounted for 29% of the variance in physical functioning (see Table 2).

Table II.

Hierarchical Regression Mode: Physical Functioning

| Model | Variable | R | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | df1,2 | F Change p | β * | t | p | sr2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||

| Biologics | .11 | .01 | .01 | .29 | 4,98 | .88 | .05 | .48 | .63 | .00 | |

| DMARDs | -.10 | -.92 | .36 | .01 | |||||||

| NSAIDs | -.02 | -.16 | .87 | .00 | |||||||

| Other | .05 | .50 | .62 | .00 | |||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| Disease activity | .33 | .11 | .10 | 5.28 | 2,96 | <.01 | -.29 | -2.97 | .00 | .08 | |

| (RADAR) DAS-28 | -.09 | -.84 | .40 | .01 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| Personal mastery | .34 | .12 | .01 | .42 | 2,94 | .660 | .04 | .43 | .67 | .00 | |

| Social network | -.08 | -.84 | .40 | .01 | |||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| Active coping | .54 | .29 | .17 | 4.20 | 5,89 | <.01 | .21 | 2.06 | .04 | .03 | |

| Passive coping | -.21 | -1.85 | .07 | .03 | |||||||

| Helplessness | -.19 | -1.69 | .10 | .02 | |||||||

| Internality | .04 | .40 | .69 | .00 | |||||||

| Perceived stress | .15 | 1.14 | .26 | .01 | |||||||

β:Standardized regression coefficient

sr2: Unique variance

Mental Health Functioning. At step 1, medication use did not contribute to mental health functioning scores, but at step 2, disease activity for 6% unique variance in mental health functioning (p<.05). Greater self-reported disease activity (be=. -25) was associated with poorer mental health scores; however, the DAS 28, as in the preceding analysis, was not significant. The entry of personal mastery and social network scores at step 3 proved highly significant, accounting for 22% unique variance; however, personal mastery, itself, accounted for 21% of the variance (be=.49), while social network was not related to mental health functioning. Coping process variables at step 4 contributed an additional 27% unique variance to mental health functioning scores. Perceived stress alone accounted for 23% of the variance in this step (be=-.69), while other variables were unrelated to mental health functioning. Overall, the model accounted for 60% of the variance in mental health functioning scores (see Table 3).

Table III.

Hierarchical Regression Model: Mental Health Functioning

| Model | Variable | R | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | df1,2 | F Change p | β * | t | p | sr2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||

| Biologics | .19 | .04 | .04 | .96 | 4,98 | .43 | -.01 | -.11 | .92 | .00 | |

| DMARDs | .08 | .74 | .46 | .01 | |||||||

| NSAIDs | -.09 | -.84 | .41 | .01 | |||||||

| Other | .14 | 1.34 | .18 | .01 | |||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| Disease activity | .32 | .10 | .06 | 3.28 | 2,96 | .04 | -.25 | -2.55 | .01 | .06 | |

| (RADAR) DAS-28 | .02 | .19 | .85 | .00 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| Personal mastery | .57 | .32 | .22 | 15.39 | 2,94 | <.001 | .49 | 5.42 | <.001 | .21 | |

| Social network | .06 | .72 | .47 | .00 | |||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| Active coping | .77 | .60 | .27 | 12.08 | 5,89 | <.001 | .03 | .36 | .72 | .00 | |

| Passive coping | -.02 | -.17 | .86 | .00 | |||||||

| Helplessness | -.07 | -.87 | .39 | .00 | |||||||

| Internality | -.02 | -.19 | .85 | .00 | |||||||

| Perceived stress | -.69 | -7.10 | <.001 | .23 | |||||||

β: Standardized regression coefficient

sr2: Unique variance

Disability (HAQ-DI). Medication use contributed 10% of the variance at step 1 to disability (p=. 053). Use of DMARDs (be=.28) and non-use of other medications (be=-.23) were associated with greater disability. Disease activity at step 2 added 26% unique variance to disability. Higher RADAR scores (be=.51) were associated with greater disability while DAS scores were not. Personal mastery and social network were not significant at step 3, but coping process variables added 16% unique variance at the final step. Higher helplessness was associated with greater disability (be=.26), while internality, passive coping, active coping and perceived stress did not contribute to disability. The model explained 50% of the variance in HAQ-DI scores (see Table 4).

Table IV.

Hierarchical Regression Model: Disability

| Model | Variable | R | R2 | R2 Change | F Change | df1,2 | F Change p | β * | t | p | sr2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||

| Biologics | .31 | .10 | .10 | 2.43 | 4,98 | .05 | -.05 | -.47 | .64 | .00 | |

| DMARDs | .28 | 2.66 | .01 | .07 | |||||||

| NSAIDs | .03 | .26 | .80 | .00 | |||||||

| Other | -.23 | -2.22 | .03 | .05 | |||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| Disease activity | .60 | .36 | .26 | 18.55 | 2,96 | <.001 | .51 | 5.98 | <.001 | .25 | |

| (RADAR) DAS-28 | .02 | .21 | .83 | .00 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| Personal mastery | .60 | .36 | .01 | .46 | 2,94 | .63 | -.06 | -.72 | .48 | .00 | |

| Social network | .06 | .70 | .49 | .00 | |||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| Active coping | .71 | .50 | .13 | 4.49 | 5,89 | <.001 | -.03 | -.32 | .75 | .00 | |

| Passive coping | .17 | 1.72 | .09 | .02 | |||||||

| Helplessness | .26 | 2.73 | <.01 | .04 | |||||||

| Internality | -.08 | -.81 | .42 | .00 | |||||||

| Perceived stress | .06 | .57 | .57 | .00 | |||||||

β: Standardized regression coefficient

sr2: Unique variance

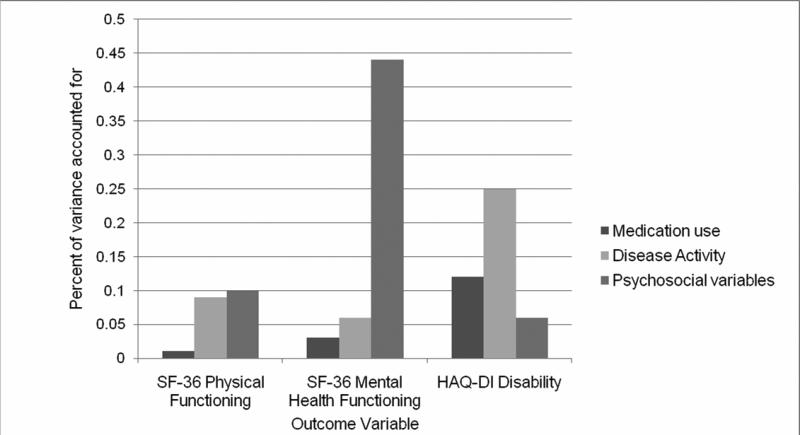

Figure 2 displays the results by each outcome variable, reflecting the respective contribution of medication use, disease activity (DAS28; RADAR), and psychosocial variables (social network, personal mastery, helplessness, internality, active coping, passive coping, and perceived stress). The pattern is quite different for mental health functioning compared to the other two outcomes. In particular, psychosocial variables played a greater role, and disease activity played a more limited role, in mental health functioning than in physical functioning and disability.

Figure II.

Variance Explained by Variable Domains

Discussion

Despite significant improvements in the medical management, treatment, and prognosis of RA, it is common for patients to experience deficits in physical and mental health functioning. This research adopted an integrated, biopsychosocial framework [16] to evaluate the relative contribution of disease activity and psychosocial factors to physical and mental health functioning outcomes in a sample of RA patients living in greater metropolitan Los Angeles. Hierarchical multiple regression isolated the sequential contribution of variables to physical functioning, mental health functioning, and disability, according to this framework. A major objective of these analyses was to determine the impact of psychosocial factors on physical and mental health and disability after controlling for medication use and disease activity. Analyses provided important, new information on the contribution of psychosocial factors and the overall relevance of this framework to functional outcomes in RA.

In general, psychosocial factors and self-reported disease activity proved very influential in explaining variability in all three outcomes. While self-reported RADAR scores were significantly correlated with physical functioning, mental health functioning, and disability scores, physician-assessed DAS28 scores were not correlated with any outcome, a finding that is consistent with previous research showing that physician-based assessments of RA disease activity may not be associated with functional outcomes or psychological variables [10,11]. Together, these findings underscore the importance of using patient-reported outcomes such as HRQOL and evaluating the clinical status of patients based on their subjective appraisal of their illness experience.

It is noteworthy that the contribution of psychosocial variables in this research varied across HRQOL domains and disability. Higher active coping was associated with better physical functioning, while passive coping and helplessness were correlated, although not significantly, with poorer physical functioning. Active coping has been shown to correlate modestly with less pain and psychological distress in RA patients [15] and more strongly with better psychosocial functioning in elderly populations with health problems [28]. Active coping refers to the ability of patients to function in spite of their pain and to actively manage their medical condition, and may be central to achieving enhanced quality of life and mechanisms of positive psychological adaptation. Active coping has proven to be a stronger determinant of positive adaptation than passive coping and helplessness, which have been shown to predict negative physical and psychological outcomes in arthritis [29], whiplash [30], and fibromyalgia [31].

Psychological factors were particularly important in explaining mental health functioning. High personal mastery and low perceived stress accounted for a major proportion of the variance in mental health functioning, although these factors did not predict physical functioning. Other research [11] has shown depression to be a major determinant of SF-36 mental health scores in RA patients. Personal mastery, unlike arthritis internality, is a global measure of perceived control that reflects a general disposition of competence that may serve as a mechanism through which better mental health functioning is achieved. Perceived stress, on the other hand, is a general indicator of burden that may be the result of numerous life stressors, including those connected with having a chronic disease. Acting influentially but in opposite directions, these factors were far more important in explaining mental health functioning than self-reported disease activity.

The findings on disability illustrated the contribution of helplessness. Helplessness independently accounted for variability in disability, over and above the effects of disease activity. Similar results have been reported elsewhere [18] and indicate that perceptions of helplessness are key to understanding deficits in functioning, but not quality of life. Specific functional problems in RA reflect idiosyncratic beliefs about the uncontrollability of pain and other aspects of the disease course but, as this research has shown, are independent of both general beliefs of mastery or specific expectancies of control over RA. That different psychological processes may be involved in quality of life and disability is not surprising in view of the disparate nature of these outcomes, including their level of specificity or generality, and their differential sensitivity to the disease process.

This study has demonstrated the applicability of a comprehensive framework for understanding HRQOL and disability in RA. A significant limitation of the study, however, was its cross-sectional design, which precluded interpretations of directionality among model variables. Future research evaluating this model longitudinally would shed light on whether psychosocial factors predict functional outcomes over time while controlling for prior levels of disease activity. Longitudinal research could also address the potential mediating roles of variables such as coping and perceived stress to these outcomes. Another limitation of the study was that participants were volunteers recruited from the community. Volunteers tend to be more mobile and possess fewer of the medical comorbidities associated with more advanced RA. A larger sample of patients with varying stages of disease progression would enable tests of the generalizability of the model, including the importance of the specific variables that were identified in this research as critical to understanding functional outcomes

In spite of these limitations, the data suggest that the evaluation of patients with RA in clinical settings should address psychosocial functioning using PROs and psychological measurements. The identification of psychosocial factors that interfere with HRQOL and lead to disability would set the stage for behavioral interventions that could facilitate management and contribute to more positive functional adaptations [32,33].

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant AR R01-049840 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institute of Health to Perry M. Nicassio. The authors have no financial gain related to the outcome of this research, and there are no potential conflicts of interest. This work was also supported in part by grants T32-MH19925, HL 079955, AG034588, AG 026364, CA119159, DA 027558, RR00827, P30-AG028748, General Clinical Research Centers Program, the UCLA Cousins Center at the Semel Institute for Neurosciences, and the UCLA Older Americans Independence Center Inflammatory Biology Core.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Department where research conducted: Department of Psychiatry, UCLA

References

- 1.Escalante A, Del Rincón I. The disablement process in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:333–42. doi: 10.1002/art.10418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verbrugge LM, Juarez L. Profile of arthritis disability: II. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:102–13. doi: 10.1002/art.21694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicassio PM. Arthritis and psychiatric disorders: disentangling the relationship. J Psychosom Res. 2009;68:183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonen A, Mau W. The economic burden of disease: comparison between rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;(4Suppl55):27, S112–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Bergman MJ. Patient questionnaires in rheumatoid arthritis: advantages and limitations as a quantitative, standardized scientific medical history. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:735–43. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichler HG, Mavros P, Geling O, Hunsche E, Kong S. Association between health-related quality of life and clinical efficacy endpoints in rheumatoid arthritis patients after four weeks treatment with anti-inflammatory agents. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:209–216. doi: 10.5414/cpp43209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tugwell P, Wells G, Strand V, Maetzel A, Bombardier C, Crawford B, et al. Clinical improvement as reflected in measures of function and health-related quality of life following treatment with leflunomide compared with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: sensitivity and relative efficiency to detect a treatment effect in a twelve-month, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:506–14. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<506::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yelin EH, Katz PP. Focusing interventions for disability among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:231–3. doi: 10.1002/art.10452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kojima M, Kojima T, Ishiguro N, Oguchi T, Oba M, Tsuchiya H, et al. Psychosocial factors, disease status, and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rupp I, Boshuizen HC, Dinant HJ, Jacobi CE, van den Bos GA. Disability and health-related quality of life among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with radiographic joint damage, disease activity, pain, and depressive symptoms. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:175–81. doi: 10.1080/03009740500343260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seawell AH, Danoff-Burg S. Psychosocial research on systemic lupus erythematosus: a literature review. Lupus. 2004;13(12):891–9. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu1083rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coty MB, Wallston KA. Problematic social support, family functioning, and subjective well-being in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Women Health. 2010 Jan;50(1):53–70. doi: 10.1080/03630241003601079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicassio PM, Wallston KA, Callahan LF, Herbert M, Pincus T. The measurement of helplessness in rheumatoid arthritis: the development of the Arthritis Helplessness Index. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:462–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown G, Nicassio P. Development of a questionnaire for assessing active and passive pain coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1987;31:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;13:535–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IIR (SCID) Biometrics Research; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein MJ, Wallston KA, Nicassio PM, Castner NM. Correlates of a clinical classification schema for the arthritis helplessness subscale. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:876–81. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen AS, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Scapacan S, Oskamp S, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. 4th ed. Sage Publications; Newbury Park(CA): 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearlin LI. The sociological study of stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1989;30:241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Larson MG, Berkman LF, Benjamin EJ. Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham Heart Study. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38:835–42. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Heijde DM, van ‘t Hof MA, van Riel PL, van Leeuwen MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB. Validity of single variables and composite indices for measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:177–181. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF, Haralson KM, Lewis-Stevens D, Kaine JL. The rapid assessment of disease activity in rheumatology (radar) questionnaire. Validity and sensitivity to change of a patient self-report measure of joint count and clinical status. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:156–62. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong AL, Wong WK, Harker J, Sterz M, Bulpitt K, Park G, Ramos B, Clements P, Paulus H. Patient self-report tender and swollen joint counts in early rheumatoid arthritis. Western Consortium of Practicing Rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2551–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvo FA, Calvo A, Berrocal A, Pevez C, Romero F, Vega E, Cusi R, Visage M, De La Cruz RA, Alarcon GS. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:536–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:167–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schanowitz JY, Nicassio PM. Predictors of positive psychosocial functioning of older adults in residential care facilities. J Behav Med. 2006 Feb 2;29(2):191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicassio PM, Greenberg MA. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral and psychoeducational interventions in the management of arthritis. In: Weisman MH, Weinblatt M, Louie J, editors. Treatment of rheumatic diseases. 2nd ed. William Saunders; Orlando(FL): 2001. pp. 147–61. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Côté P. The role of pain coping strategies in prognosis after whiplash injury: passive coping predicts slowed recovery. Pain. 2006;124(1-2):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicassio P, Schoenfeld-Smith K, Radojevic V, Schuman C. Pain coping mechanisms in fibromyalgia: relationship to pain and functional outcomes. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1552–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon K, Keefe F, Scipio C, Perri L, Abernethy A. Psychological interventions for arthritis pain management in adults. Health Psychol. 2007;26:241–50. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicassio PM. The significance of behavioral interventions for arthritis. In: Weisman MH, Weinblatt ME, Louie JS, Van Vollenhoven RF, editors. Targeted treatment of the rheumatic diseases. 1st ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 397–407. [Google Scholar]