Abstract

Early language development sets the stage for a lifetime of competence in language and literacy. However, the neural mechanisms associated with the relative advantages of early communication success, or the disadvantages of having delayed language development, are not well explored. In this study, 174 elementary school-age children whose parents reported that they started forming sentences ‘early’, ‘on-time’ or ‘late’ were evaluated with standardized measures of language, reading and spelling. All oral and written language measures revealed consistent patterns for ‘early’ talkers to have the highest level of performance and ‘late’ talkers to have the lowest level of performance. We report functional magnetic resonance imaging data from a subset of early, on-time and late talkers matched for age, gender and performance intelligence quotient that allows evaluation of neural activation patterns produced while listening to and reading real words and pronounceable non-words. Activation in bilateral thalamus and putamen, and left insula and superior temporal gyrus during these tasks was significantly lower in late talkers, demonstrating that residual effects of being a late talker are found not only in behavioural tests of oral and written language, but also in distributed cortical-subcortical neural circuits underlying speech and print processing. Moreover, these findings suggest that the age of functional language acquisition can have long-reaching effects on reading and language behaviour, and on the corresponding neurocircuitry that supports linguistic function into the school-age years.

Keywords: late talkers, language processing, reading, fMRI

Introduction

Early language development provides a foundation for the development of later language and literacy skills. Spoken language milestones in the first few years of life are frequently found to be delayed in children who show language and literacy problems later in life, implying that early spoken language development can play a substantial role in school-age oral and written language performance (Scarborough, 1990; Lyytinen et al., 2001, 2004a, b). Although the cognitive-behavioural outcomes of ’late talkers’ have been previously explored, the associated neurobiological characteristics of children who are early or late talkers, such as the neural circuitry for speech and print processing, are not well characterized. One way to begin to understand the neural underpinnings of children who have relative success or failure with early spoken language is through fMRI, which can now be routinely done successfully in young school-age children.

Children typically speak their first words at around 12 months and begin to put words together prior to 2 years (Zubrick et al., 2007). It has been argued that there are sensitive periods of language development (Locke, 1997) and that children who fail to achieve the appropriate language milestones in the first years of life are at risk for later problems in receptive and expressive language during school age and beyond. For example, cohorts of late talkers followed in several studies (Scarborough and Dobrich, 1990; Paul et al., 1997; Stothard et al., 1998; Rescorla, 2002, 2005, 2009) provide evidence for persisting delays in vocabulary and oral comprehension, reading decoding, spelling and reading comprehension. However, these differences do not always reach statistical significance, nor does the significantly lower performance of late talkers always reflect group means that are in a range suggesting reading or language impairment. For example, Rescorla’s longitudinal studies (2002, 2005, 2009) have shown inconsistent patterns, with late talkers having significant reading problems at some ages but not others, suggesting instability and/or heterogeneity among this group. Paul et al. (1997) reported that a history of late talking was not associated with significant differences in reading or spelling in second graders, but late talkers with persisting language problems did show evidence of weak phonological awareness – a robust predictor of reading skill and dyslexia. However, Scarborough and Dobrich (1990) observed persisting literacy problems in second graders who had a history of being late to form sentences. Similarly, a large-scale Finnish longitudinal study has shown that late onset of word combinations reliably distinguishes children at familial risk for dyslexia from children not at such risk (Lyytinen et al., 2001). Thus, there is support for the notion that late talkers may demonstrate persisting (but sometimes subtle or subclinical) differences in spoken and written language.

Late talkers, as defined here, are delayed in combining words to form early sentences; therefore, mechanisms associated with sentence formation should be considered. Early word combinations require, at least, sufficient word knowledge to be able to relate two or more words and sufficient speech motor control to sequence articulatory gestures to form a multisyllabic utterance. Thus, both adequate word-learning mechanisms and adequate speech motor control must have developed in order to combine words. It is therefore reasonable to assume that neural regions associated with lexical and speech motor learning play a role in early sentence formation.

Ullman and Pierpont (2005) speculated that delayed language development, along with other subtle neurocognitive deficits, can be explained by problems in the procedural memory system. This is a large network involving many cortical and subcortical regions. Ullman and Pierpont (2005) suggest that the striatum (putamen and caudate nucleus), known to be involved in initiating motor movement as well as in procedural memory, is critical in learning new skills (sensory motor as well as cognitive linguistic). Thus, the functioning of these regions should play a pivotal role in spoken language acquisition. If inherent differences in striatum are indeed associated with delays in spoken language, one question is whether there are residual effects in the striatum several years later, when children are of an age where functional neuroimaging can be performed.

A few studies of children with a history of speech-language delay, including children with specific language impairment or developmental verbal dyspraxia, have revealed a variety of structural and functional differences in brain. Structurally, several studies have shown differences in children with language impairments that include smaller pars triangularis in the left hemisphere and atypical asymmetries in perisylvian regions (Jernigan et al., 1991; Plante et al., 1991; Gauger et al., 1997). An fMRI study of adolescents and adults (11–70 years) in a Finnish family with specific language impairment revealed low activation in middle temporal gyrus/superior temporal sulcus when participants were passively listening to words and pseudowords (Hugdahl et al., 2004); however, group differences were not reported due to the small sample size, and neural processing of print was not examined. The current report addresses these limitations by focusing on a larger sample of elementary school-age children with histories of early, on-time and late talking.

Much of the knowledge of the neural differences associated with congenital spoken language problems comes from studies of the KE family, which includes several members with a rare mutation of the FOXP2 gene resulting in deficits in syntax and verbal dyspraxia (see Vargha-Khadem et al., 2005 for a review). Anatomical studies of the brains from KE family members have revealed reduced grey matter bilaterally in the cerebellum, caudate nucleus and inferior frontal gyrus (Vargha-Khadem et al., 1998; Watkins et al., 2002; Belton et al., 2003). Functional imaging of members of this family has shown increased activation in the left caudate nucleus and Broca’s area in the inferior frontal gyrus, as well as reduced activation in oral regions of primary sensorimotor, cingulate and supplementary motor cortices during speech (Liegeois et al., 2003). However, this represents a unique subset of individuals with developmental language differences, as FOXP2 mutation is quite rare among cases of spoken language delay (Meaburn et al., 2002). The present study, therefore, focuses on a sample of children who are late in combining words into sentences but who do not necessarily share a unique genetic anomaly.

This study investigates the impact of language development (early word combinations) on language and literacy in elementary school in order to provide novel insights into the neural systems associated with early and late talking. Specific accounts of the underlying neural features of the language learning systems may help elucidate differences at the behavioural level. Early talkers can be thought of as having a neurolinguistic system that is well suited for early verbal communication, which could prepare them for success in spoken and written language when they reach school age. In general, early language achievement in one domain accompanies success in other domains (although not universally). Thus, children who are early in forming sentences would be predicted to have the most success in later spoken and written language and therefore more efficient neural systems for language processing. In contrast, based on previous studies, we hypothesize that children who are late talkers will be, on average, lower in several areas of oral language (including vocabulary, oral comprehension, phonological processing) and literacy (including reading accuracy, reading fluency, reading comprehension and spelling). fMRI will allow us to examine the role of traditional cortical language areas (e.g. Wernicke’s area in the superior temporal gyrus) and subcortical regions (e.g. the striatum) in processing of speech and print in children who were early and late talkers. Based on previous data and predictions by Ullman and Pierpont (2005), we expect that regions associated with skill consolidation (the striatum), as well as traditional language-related regions, will show less efficient processing in late talkers during language-related tasks.

Materials and methods

Participants

As part of ongoing longitudinal studies of reading development and neurobiology, children were recruited through public notices and contacts with local schools. Recruitment focused on obtaining a broad sample of children with various reading, family and sociodemographic characteristics. Children were seen for behavioural assessment, and on a separate visit, many of these children underwent fMRI. All procedures were approved by the local Institutional Review Board and families participated in exchange for payment. Parents of 174 children [ages 4 years 10 months to 12 years 8 months (mean 8 years 1 month, SD 17 months)] reported on the child’s early language development, and these participants formed the basis for the analysis. All were native English speakers, and five participants (all in the on-time group), were exposed to another language at home. A subsample of 48 children who received fMRI is also described (see below).

Developmental history and group status

As part of study protocol, parents reported on their child’s developmental milestones. Parents were asked to report categorically whether they believed their child spoke two- to three-word sentences early, on-time or late, which formed the bases for the groups in the present study (hereafter early, on-time and late talkers). In addition, parents provided an age estimate of early sentence formation. None of the early talkers were reported to have spoken their first sentences after 24 months, and none of the late talkers was reported to have spoken sentences before 24 months. Parent report is commonly used in studies of early language development and is, on the whole, quite reliable (Rescorla and Alley, 2001; Zubrick et al., 2007). We used this report of early word combinations to provide an estimate of early spoken language development because word combinations (i) require greater articulatory control than single words; (ii) have been found to relate strongly to later language and literacy skills (Scarborough and Dobrich, 1990; Lyytinen et al., 2001); and (iii) have been shown to be a highly reliable estimate for ‘late language emergence’ (cf. Zubrick et al., 2007). Based on these ratings, the sample consisted of 49 early, 89 on-time and 36 late talkers. This proportion of late talkers (20.6%) is similar to a recent epidemiological estimate of the prevalence of late talkers who were also defined as being late in combining words (19.1%; Zubrick et al., 2007).

Because we relied on this retrospective report for determining group classification, converging evidence from parent report was sought to validate the groups. A similar three-category question asking when the child began producing first words was found to be strongly associated with parent report of the child producing two- to three-word sentences (Gamma = 0.639, P < 0.001). Also, Table 1 shows that children who were late talkers were more likely to have received speech therapy, were more likely to have been diagnosed as dyslexic by a school or clinic and were estimated by parents to begin combining sentences at a later age than the other two groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and descriptive information from the three talker groups

| All participants |

fMRI subgroup |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-time | Late | Early | On-time | Late | |

| Male (n) | 23 | 49 | 26 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Female (n) | 26 | 40 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 |

| Mean age tested (years;months) | 8;1 | 8;2 | 7;11 | 8;5 | 8;6 | 8;9 |

| Median reported age speaking 2–3 word sentences (years) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Percent received speech therapy | 9% | 12% | 67% | 18% | 18% | 56% |

| Percent diagnosed dyslexic by school or clinic | 7% | 4% | 30% | 6% | 6% | 25% |

Data based on parent report. Not all parents provided responses to all questions.

Behavioural battery

Children’s verbal and performance intelligence quotient (IQ) was measured using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999). Receptive vocabulary was measured using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (Dunn and Dunn, 1997). Phonological processing skills were measured using the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (Wagner et al., 1999).

Reading skills were measured using several standardized tests. The Gray Oral Reading Test (Wiederholt and Bryant, 2001) requires reading passages of increasing length and difficulty (scored for rate and accuracy) and answering comprehension questions about those passages. The Test of Word Reading Efficiency (Torgesen et al., 1999) measures both time and accuracy for oral reading of words and pseudowords. Several subtests of the Woodcock Johnson-III Tests of Achievement (Woodcock et al., 2001) that address literacy skills were also administered, including Word Attack, Letter-Word Identification, Passage Comprehension, Reading Fluency and Spelling. Subtests administered from the Woodcock Johnson-III Test assessing oral language included Story Recall, Understanding Directions, Picture Vocabulary and Oral Comprehension.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

Most of the children who participated in the behavioural testing also participated in an fMRI language processing task that requires picture/word identification (see Frost et al., 2009 for detailed description of the task, data acquisition and pre-processing procedures). This task involves the presentation of a picture on a screen (e.g. picture of a dress) followed by a series of spoken stimuli or printed stimuli. Print stimuli appear underneath the picture for 2 s. To ensure that the child attended to the stimuli, the child was required to respond by button press to indicate whether the spoken or printed stimuli matched or did not match the picture. Conditions considered in this report are auditory and printed monosyllabic words or non-words (e.g. DREAK). We limit the analysis to the trials (80%) that are mismatches to allow for a common comparison across response conditions. An event-related design was used, presenting trials at jittered intertrial intervals of 4–7 s, with occasional longer trials to facilitate event-related analysis. All conditions were represented in each run, and up to 10 runs were completed per participant.

Prior to the fMRI session, participants were familiarized with the procedure and scanning environment using a mock scanner. A Siemens 1.5 T Sonata scanner was used for all sessions. Activation images were collected with a standard head coil using single shot, gradient echo, echo-planar acquisitions (flip angle 80°; echo time 50 ms; repetition time 2000 ms; field of veiw 20 × 20 cm; 6 mm slice thickness, no gap; 64 × 64 × 1 number of excitations) at 20 slice locations placed oblique to provide whole brain coverage. High-resolution 1 mm isotropic anatomical images were gathered for 3D reconstruction.

Data analysis was performed using software written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Images were corrected for slice acquisition time, corrected for motion with Statistical Parametric Mapping (Friston et al., 1995), and spatially smoothed (5.15 mm full-width at half maximum Gaussian filter). Images were excluded if they exceeded a tolerance of 2 mm displacement or 2o rotation from the first image in the functional series, or if they exceeded an image-to-image change of 1 mm displacement or 1o rotation. For each subject, regression-based estimation was used to obtain the haemodynamic response at each voxel and for each condition, without prior specification of a reference function. These parameters estimated the mean response for each condition from −3 to +15 s relative to stimulus onset, and individual activation maps were created to estimate the mean difference between a baseline (0–3 s before onset) and an activation period (3–8 s post-onset). These regression estimates were used to test for effects of interest. Each participant’s data were transformed to Montreal Neurological Institute space by mapping the high resolution anatomical to the standard ‘Colin’ brain using BioImageSuite (http://www.bioimagesuite.org).

In-scanner task accuracy was taken into consideration, and we chose to exclude data from two participants (both in the on-time group) who failed to respond to at least 40% of the trials or were below 50% accurate. There were no significant group differences in response accuracy, reaction times or percent of trials with null responses (all P > 0.10).

In this study, children were at least 6 years old when they participated in fMRI procedures. Although the data we present include only one fMRI session per participant, our longitudinal design involves repeating the fMRI protocol at the beginning of the study and again two years later. For six participants, the scan at entry to the study was not used (due to non-participation, non-compliance, movement artefact, etc.), but the participants had usable fMRI data on the same task at the end of the study that were included. fMRI data were therefore available for 84 participants (24 early, 44 on-time, 16 late). To balance the groups, we therefore limited the early and on-time groups to 16 participants who were similar to the late group in age, gender and performance IQ (note that highly similar results are observed when all 84 fMRI scans are included in the analysis). We considered it important to match on performance IQ because poorer language and literacy outcomes have been observed in children with early communication delays when there are concomitant nonverbal cognitive delays (Stothard et al., 1998). The fMRI sample consisted of 48 children ages 6 years 6 months to 10 years 10 months.

Results

Behavioural results

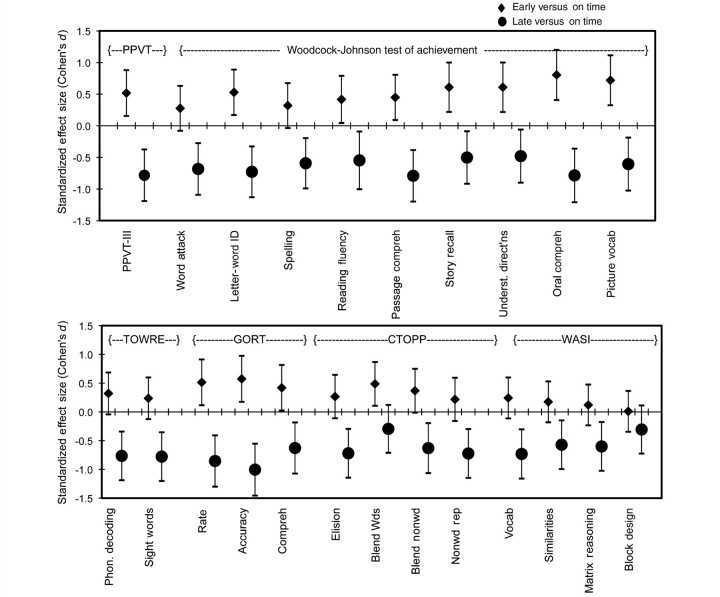

Early talkers showed a significant advantage over the on-time group in many aspects of spoken and written language, whereas late talkers performed lower on virtually all language and literacy-related tasks. Standardized effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (Cohen’s d, using Hedge’s correction) are shown in Fig. 1 using the on-time group as a reference with which the early and late talker groups are compared (essentially, confidence intervals that do not cross zero indicate a significant difference between the on-time group and the two groups shown in the figure). Univariate ANOVAs testing the effect of talker group on each subtest shown in Fig. 1 revealed significant main effects for Group across all Behavioural measures (P < 0.01) except for a nonverbal subtest, the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Block Design.

Figure 1.

Standardized effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (Cohen’s d, using Hedge’s correction) showing group differences between early versus on-time talkers (diamonds) and on-time versus late talkers (circles) on several measures of language, literacy and cognition. Confidence intervals that do not cross 0 reflect significant group differences. PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III; TOWRE = Test of Word Reading Efficiency; GORT = Gray Oral Reading Test; CTOPP = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

For significance testing we present a more conservative approach by examining performance in a variety of school-age language and literacy domains using multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) to evaluate the effects of talker group (in most cases, not all children completed all tasks, resulting in a reduction in the number of subjects included in each analysis). All MANCOVAs evaluate the effects of talker groups while covarying performance IQ (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Matrix Reasoning and Block Design). Results are shown in Table 2. Significant effects of talker group remain for these spoken and written language domains when performance IQ is controlled, although performance IQ is significantly associated with talker groups (P < 0.01 in all MANCOVAs). The main effect of talker group is largest for reading accuracy, followed by oral language, vocabulary, reading fluency, reading comprehension and spelling (all P < 0.01, partial η2 > 0.06). The MANCOVA testing the effect of talker group on phonological processing failed to reach significance (P = 0.103), although the group means follow a similar pattern to other behavioural measures.

Table 2.

Effect of talker group on school-age language and literacy performance

| MANOVA model name/construct | Dependent variables | Unadjusted group means (SD) |

Main effect of groupa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-time | Late | F (df) | P | partial η2 | ||

| Vocabulary n = 135 | WJ Picture Vocabulary | 119.1 (11.4) | 110.9 (11.8) | 105.9 (10.6) | 4.16 (6,258) | 0.001 | 0.088 |

| WASI Vocabulary | 59.5 (9.0) | 54.3 (9.8) | 46.4 (12.6) | ||||

| PPVT-III | 121.7 (12.1) | 113.3 (12.2) | 104.7 (12.9) | ||||

| Oral language n = 137 | WJ story recall | 123.2 (10.0) | 114.3 (14.1) | 108.9 (15.7) | 3.81 (8,260) | <0.001 | 0.105 |

| WJ directions | 115.1 (12.2) | 108.9 (10.1) | 104.0 (14.4) | ||||

| WJ oral comp | 125.6 (10.7) | 115.6 (12.0) | 107.0 (13.3) | ||||

| WASI similarities | 61.7 (8.9) | 58.2 (7.4) | 51.5 (14.0) | ||||

| Phonological processing n = 140 | CTOPP elision | 12.0 (3.2) | 11.28 (3.1) | 9.5 (2.8) | 1.68 (8,266) | 0.103 | 0.048 |

| CTOPP blending words | 12.1 (2.9) | 10.8 (2.3) | 10.2 (1.8) | ||||

| CTOPP blending non-words | 12.9 (2.4) | 12.0 (2.7) | 10.7 (1.8) | ||||

| CTOPP non-word repetition | 10.0 (2.6) | 9.5 (2.3) | 9.4 (2.4) | ||||

| Reading accuracy n = 132 | WJ letter-word identification | 120.3 (14.0) | 110.4 (14.5) | 99.5 (11.3) | 3.84 (10,248) | <0.001 | 0.134 |

| WJ word attack | 114.6 (12.3) | 109.4 (12.5) | 102.5 (10.8) | ||||

| GORT accuracy | 10.1 (3.5) | 8.2 (3.4) | 5.1 (2.5) | ||||

| TOWRE phonemic decoding | 111.1 (15.0) | 104.6 (16.4) | 93.0 (12.9) | ||||

| TOWRE sight words | 112.3 (15.0) | 106.9 (15.6) | 93.0 (13.1) | ||||

| Reading fluency n = 127 | WJ reading fluency | 116.3 (16.6) | 107.4 (18.9) | 96.8 (16.4) | 4.88 (4,244) | 0.001 | 0.074 |

| GORT fluency | 11.4 (3.5) | 9.3 (3.9) | 6.0 (3.1) | ||||

| Reading comprehension n = 133 | WJ passage comprehension | 114.2 (13.5) | 105.4 (13.6) | 96.5 (10.9) | 4.51 (4,256) | 0.002 | 0.066 |

| GORT reading comprehension | 12.3 (4.4) | 10.6 (3.9) | 8.6 (3.5) | ||||

| Spellingbn = 157 | WJ spelling | 15.8 (20.0) | 109.7 (18.6) | 98.9 (15.7) | 4.88 (2,153) | 0.009 | 0.06 |

MANOVA = multivariate analysis of variance; WJ = Woodcock Johnson-III Test; PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III; TOWRE = Test of Word Reading Efficiency; GORT = Gray Oral Reading Test; CTOPP = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

a Main effect of group based on Wilks’ Lambda, and include Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Performance IQ as a covariate (P < 0.01 in all models).

b Spelling analysed using univariate ANOVA with Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence Performance IQ as covariate.

Table 3 presents data from the subset of 48 children included in the fMRI analysis on several of our behavioural tasks, demonstrating the same patterns as the larger cohort. In some cases, the effect sizes are smaller than in the larger cohort, presumably because we chose to select conservatively early and on-time talkers who were similar in performance IQ to late talkers. Overall, our results are consistent with prior research indicating that school-age oral and written language skills are lower for children who are late talkers. However, in this sample the late talker group means, while low, are still within the normal range on most of these standardized tests, indicating that not all of our late talkers had clinically significant language and literacy delays; they are, however, on average, worse than early and on-time talkers. These mean differences and data in Table 1—demonstrating that a greater proportion of late talkers had received speech therapy and had been diagnosed as dyslexic—highlight that late talking is a risk factor for clinically significant language and literacy problems.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for 48 children included in fMRI analysis

| Group means (SD) |

Main effect of group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | On-Time | Late | F (df) | P | |

| Age (years;months) | 8;5 (15 mo) | 8;6 (16 mo) | 8;9 (16 mo) | 0.31 (2,45) | 0.731 |

| WASI | |||||

| Performance IQ | 108 (12) | 101 (10) | 102 (15) | 1.7 (2,44) | 0.202 |

| Verbal IQ | 112 (12) | 107 (12) | 103 (19) | 1.4 (2,44) | 0.249 |

| WJ Broad reading | |||||

| Word attack | 112 (11) | 108 (12) | 102 (12) | 3.4 (2,45) | 0.043 |

| Letter-Word identification | 117 (15) | 107 (14) | 100 (11) | 6.0 (2,45) | 0.005 |

| WJ oral language | |||||

| Story recall | 120 (9) | 108 (16) | 107 (16) | 4.4 (2,45) | 0.017 |

| Understanding directions | 112 (12) | 106 (9) | 105 (11) | 2.5 (2,45) | 0.093 |

| Picture vocabulary | 113 (10) | 110 (9) | 108 (11) | 1.1 (2,44) | 0.337 |

| Oral comprehension | 125 (14) | 110 (10) | 110 (12) | 8.5 (2,45) | 0.001 |

| GORT fluency | |||||

| Accuracy | 9.2 (3.4) | 6.9 (3.2) | 5.7 (3.2) | 4.4 (2,42) | 0.018 |

| Rate | 12.2 (3.5) | 9.3 (3.7) | 8.6 (3.0) | 4.7 (2,42) | 0.015 |

| TOWRE total word reading | |||||

| Sight words | 108 (18) | 102 (13) | 97 (11) | 2.6 (2,45) | 0.086 |

| Phonemic decoding | 111 (14) | 103 (14) | 96 (12) | 4.4 (2,45) | 0.018 |

| PPVT-III | 116 (11) | 113 (9) | 107 (10) | 2.7 (2,44) | 0.080 |

| fMRI task | |||||

| Reaction time (ms) | 1609 (231) | 1664 (324) | 1490 (276) | 1.6 (2,45) | 0.209 |

| Sensitivity (A’) | 0.93 (0.050) | 0.87 (0.120) | 0.90 (0.080) | 2.2 (2,45) | 0.127 |

mo = months; WJ = Woodcock Johnson-III Test; PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III; TOWRE = Test of Word Reading Efficiency; GORT = Gray Oral Reading Test; CTOPP = Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging results

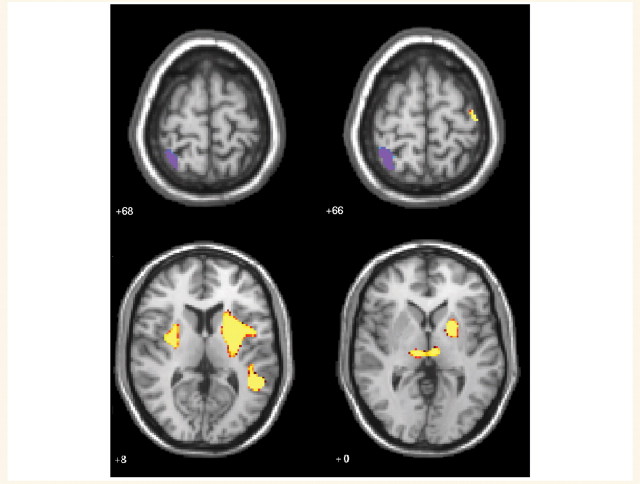

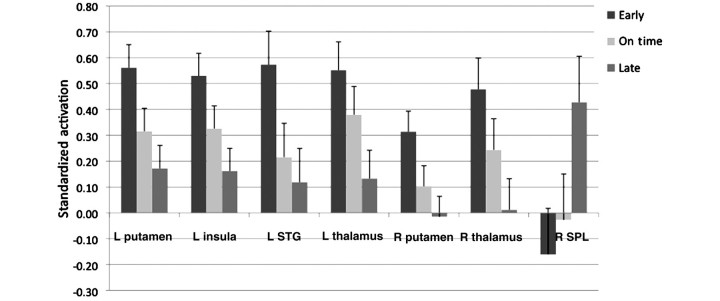

Our fMRI analyses focus on talker group differences in processing of speech and print. Whole-brain analyses were run to examine functional activation differences between the early and late talkers on auditory and visual words and non-words. In-scanner performance was significantly above chance performance for all participants (P < 0.05 based on binomial tests compared with chance performance; accuracy greater than 59% for print and above 61% for speech for all children in these groups). The groups did not differ in sensitivity (Table 3) or percent accuracy for speech [medians: early 91%, on-time 88%, late 91%, χ2 (2) = 3.2, P = 0.19] or print [medians: early 92%, on-time 85%, late 91%, χ2 (2) = 1.6, P = 0.45). Because none of the effects reported here was qualified by modality, group analyses collapsed spoken and printed stimuli. [A single region in right superior frontal gyrus (Brodmann’s area 11) showed a print-speech modality interaction that met the threshold of P < 0.01 false discovery rate corrected with a cluster of 10 contiguous voxels. The form of the interaction was such that print was greater than speech for the early talkers, and speech was marginally greater than print for the late talkers.] Regions associated with differences between early and late talkers are shown in Table 4. At a threshold of P < 0.0001 (false discovery rate corrected), there were strong group differences in activation in several regions, including left superior temporal gyrus, left putamen/globus pallidus (extending into the head of caudate), right putamen, left insula and bilateral thalamus. In each of these areas, late talkers demonstrated significantly less activation than early talkers in both speech and print conditions (Fig. 2). In order to illustrate this difference, we extracted activation values for functionally defined 3D regions of interest from this omnibus ANOVA contrast (one large functional region of activation of putamen/globus pallidus extending into insula was separated into two regions using anatomical landmarks). Although individual activation levels showed within-group variability (for illustration see plots of left putamen and left thalamus, Supplementary Fig. 1), each region showed a monotonic decreasing function in activation from early to on-time to late talkers (Fig. 3). In contrast, right superior parietal lobule showed the opposite pattern (Fig. 3), with the late talkers activating this region and early talkers showing deactivation.

Table 4.

Regions associated with differences between early and late talkers (P < 0.0001, false discovery rate corrected)

| Volume (mm3) | t-Value | Peak P-value | MNI coordinates (peak voxel) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Early > late | ||||||

| Left globus pallidus/putamen | 5960 | 5.79 | <0.00000000 | −25 | 8 | −4 |

| Left insula | 3384 | 5.61 | 0.00000006 | −30 | 22 | 16 |

| Left superior temporal extending to middle temporal | 3056 | 5.68 | <0.00000000 | −48 | −42 | 10 |

| Right globus pallidus/putamen | 2768 | 5.68 | <0.00000000 | 30 | −1 | 10 |

| Left cingulate/superior frontal | 1256 | 5.74 | <0.00000000 | −12 | −12 | 52 |

| Right inferior occipital | 728 | 4.94 | 0.00000119 | 36 | −84 | −8 |

| Right superior frontal/precentral | 576 | 5.03 | 0.00000077 | 24 | −16 | 50 |

| Right precuneus | 568 | 5.13 | 0.00000048 | 14 | −62 | 48 |

| Right inferior superior frontal | 512 | 7.18 | <0.00000000 | 14 | 68 | −16 |

| Left thalamus | 504 | 4.94 | 0.00000113 | −6 | −18 | 0 |

| Right thalamus | 488 | 4.96 | 0.00000107 | 14 | −20 | 0 |

| Right middle occipital | 408 | 5.18 | 0.00000036 | 28 | −88 | 4 |

| Left precentral | 376 | 6.10 | <0.00000000 | −44 | −14 | 62 |

| Right posterior putamen/claustrum/insula | 368 | 4.27 | 0.00002456 | 36 | −6 | −4 |

| Left superior frontal | 264 | 4.89 | 0.00000149 | −8 | 4 | 56 |

| Left inferior temporal | 248 | 5.13 | 0.00000048 | −46 | −10 | −38 |

| Left anterior precentral | 240 | 4.71 | 0.00000352 | −36 | 4 | 44 |

| Left precuneus | 232 | 4.39 | 0.00001490 | −12 | −50 | 52 |

| Left fusiform/lateral occipitotemporal sulcus | 232 | 4.67 | 0.00000411 | −42 | −46 | −7 |

| Late > early | ||||||

| Right superior parietal lobule | 1336 | 5.68 | <0.00000000 | 36 | −50 | 66 |

| Left middle temporal | 1016 | 5.67 | <0.00000000 | −72 | −26 | −4 |

| Right posterior inferior parietal sulcus | 840 | 5.71 | <0.00000000 | 38 | −74 | 46 |

| Right cerebellum | 640 | 5.02 | 0.00000089 | 30 | −56 | −46 |

| Left superior parietal lobule | 488 | 4.99 | 0.00000089 | −32 | −54 | 62 |

| Left middle frontal | 400 | 5.05 | 0.00000066 | −36 | 30 | 40 |

| Left posterior inferior temporal | 320 | 5.70 | <0.00000000 | −60 | −60 | −20 |

| Right lingual | 256 | 5.44 | 0.00000012 | 14 | −90 | −10 |

| Left inferior frontal | 192 | 4.86 | 0.00000173 | −48 | 44 | 6 |

MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute.

Figure 2.

Axial view of brain regions with significant group differences when processing print and speech. Late talkers show greater activation than early talkers in superior parietal lobe (top z = +68, +66). Early talkers show greater activation in left and right thalamus, left superior temporal gyrus, right putamen and left putamen/globus pallidus/insula (bottom, z = +8, +0). Images are presented in radiological convention with the left hemisphere on the right side of the images. A univariate threshold of P < 0.0001 was applied, corrected for mapwise false discovery rate with a cluster threshold of ten contiguous significant voxels.

Figure 3.

Mean activations by group in response to speech and print during fMRI task in selected functionally defined brain regions. Error bars represent 1 SEM. STG = superior temporal gyrus; SPL = superior parietal lobule.

Although our primary focus for the fMRI analyses was on differences in activation patterns for the matched talker groups, we conducted a number of correlational analyses to explore activation patterns further. Analysis indicated that the activations in the regions of interest were not qualified by participant age (r < 0.21, P > 0.09 for all). Additional correlational analyses indicated that activation patterns in subcortical regions were weakly-to-moderately correlated with behavioural scores on reading and oral language (Supplementary Table 1). Activations in the left putamen were correlated with performance on several tasks; for example, activations in response to print showed positive correlations with the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing–Blending Words subtest (r = 0.43) and the Woodcock Johnson-III Spelling subtest (r = 0.36), among others. Activation in left thalamus in response to print correlated with behavioural scores from reading rate on the Gray Oral Reading Test (r = 0.40) and Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing–Blending Non-words subtest (r = 0.49), among others. Among the strongest brain-behaviour correlations were the left superior temporal gyrus in response to print and scores on the Woodcock Johnson-III Spelling subtest (r = 0.51) and Woodcock Johnson-III Letter-Word Identification subtest (r = 0.51). These analyses indicate that the regions that separate early and late talkers are also regions associated with individual performance on language and literacy tasks at school age.

Discussion

Behavioural findings

The current study replicates previous behavioural findings for the impact on language and literacy of being a late talker (Scarborough and Dobrich, 1990; Paul et al., 1997; Stothard et al., 1998), and also shows reliable advantages for early talkers, who perform better than children who began forming sentences on-time. The consistent effect of talker group across language and literacy domains supports much prior work indicating that early spoken language skills support future successes. As indicated by the effect sizes (Fig. 1), group differences are moderate but consistent across most language and literacy measures. The large sample size allowed us to investigate the effect of talker group while controlling for performance IQ, which is often ignored due to statistical power limitations. Results indicated that although performance IQ was significantly related to language and literacy outcomes, group differences remained for measures of vocabulary, oral language, reading comprehension and word reading after controlling for performance IQ. The fact that the talker groups were not significantly different in phonological processing (once performance IQ is taken into account) is perhaps surprising given that prior work has pointed to phonological awareness deficits in late talkers (Paul et al., 1997) and that word reading skills (which rely on phonological awareness) were found to differ among the groups. In addition to these group mean differences, individual patterns based on our inspection of the data suggest that a greater proportion of late talkers were at risk for reading problems (i.e. below 90 on at least one measure of reading). Given the increased risk, understanding of these neurobiological markers is critical.

Functional neuroimaging findings

Talker group status was strongly related to neural activation patterns during relatively simple linguistic tasks, including listening to and reading monosyllabic words and non-words. These differences in activation exist despite the fact that the groups did not differ in response accuracy and reaction time during the task; this suggests that the lower signal is not an artefact of reduced skills or performance but is likely to reflect atypical organization of these components when processing print or speech. Cortical differences in activation, including differences in superior temporal gyrus in response to speech and print, are consistent with studies that demonstrate the role of this region in understanding speech (Hugdahl et al., 2004) and processing print (Pugh et al., 2000, 2001). Additionally, differences in the insula, which has been associated with the formation of speech motor plans (Wise et al., 1999), provide a plausible account of the neural bases of late onset of spoken language.

A particularly robust finding was that two subcortical regions, putamen and thalamus, distinguish the groups in terms of processing linguistic stimuli. To some degree, this finding is consistent with predictions made by Ullman and Pierpont (2005), who hypothesized that regions implicated as part of the procedural memory system, including striatum, might be at the root of language learning difficulties. In their view, the ability to learn new cognitive-linguistic skills, and to maintain control over those skills, should rely heavily on the integrity of the striatum and its projections to the thalamus and frontal cortex. The present study cannot determine whether these regions are causally related to language skill, or whether congenital differences in these regions existed, but the fMRI results are generally in accord with findings from previous studies of functional differences in adults with congenital spoken language problems due to a genetic anomaly (Vargha-Khadem et al., 2005).

Thalamus and putamen have been implicated in adult language function—for example, in lesion studies (Alexander et al., 1987). However, their prominent role in early language proficiency, suggested by these data, is a new discovery. With regard to adult studies, the links are strong. For example, a positron emission tomography study of healthy adults detecting linguistic anomalies revealed relationships between phonological skills and the left striatum (Tettamanti et al., 2005). A case study of a patient with bilateral damage involving the putamen and head of the caudate revealed deficits in sequencing of articulatory gestures and in syntactic comprehension (Pickett et al., 1998). Additionally, a study of adults with Huntington’s disease (associated with striatal degeneration) has implicated the striatum in learning rules from artificial languages (De Diego-Balaguer et al., 2008). The subcortical links between putamen and cortical regions associated with mouth movements and speech production have been identified (Henry et al., 2004), and it has been argued that the putamen has direct, unidirectional influences on superior temporal gyrus activation when participants process phonological information (Booth et al., 2007), suggesting that the putamen might function as a gateway to language proficiency. Seghier and Price (2009) reported that the putamen is an important region connecting the circuits that are engaged in oral reading. High-level language skills in adults (i.e. detecting semantic relations with distracters) have also been shown to rely heavily on subcortical structures, especially putamen, caudate and thalamus (Ketteler et al., 2008). Additionally, the thalamus has been implicated in several studies of dyslexia, with clear cellular anomalies in this region (Galaburda et al., 1985, 2006); the functional differences we observe in the thalamus among children at-risk for literacy problems supports those histological findings. The extant literature therefore supports the supposition that if articulatory proficiency, language learning, phonological skills and reading rely on the integrity of these subcortical structures (striatum, thalamus) in young children, and these structures are underengaged during simple language processing tasks, early language development would be likely to suffer. The putamen has long been recognized for being involved in initiation of motor movements, and deficits therein could be associated with delayed speech motor control. Overall, the present study provides initial evidence consistent with the notion that these regions may play a critical role in early spoken language acquisition and subsequent risk for later reading and listening difficulties.

Given the observed differences in subcortical motor regions as well as cerebellum, we speculate that these children with delayed onset of forming sentences might also show subtle differences in motor control (perhaps both speech and non-speech), which has been observed in prior studies of late talkers (Viholainen et al., 2002), children with reading disabilities (Wolff et al., 1984) and those with language learning difficulties (Crary and Anderson, 1990; Powell and Bishop, 1992).

The right superior parietal lobule, which has been associated with shifting attention, was activated to a greater extent in late talkers than in early talkers. Superior parietal lobule activation has been found to relate to visually shifting attention in space (e.g. shifting attention from a picture to a printed word in our fMRI task) and shifting attention between modalities (e.g. shifting from a picture to a spoken word in our fMRI task) (Coull and Frith, 1998; Behrmann et al., 2004; Fan et al., 2005). This might suggest either a compensatory mechanism to perform the task, or it might indicate that the task was more attentionally demanding for the late talkers.

Although we have identified neural differences in young school-age children with histories of being early and late talkers, it remains to be determined why these differences exist. That is, a combination of biological, genetic, social and environmental/experiential influences may be related to early spoken language milestones, neural development and the subsequent behavioural outcomes and neural characteristics observed (Dennis, 2000). Also, whether similar brain differences exist in response to speech at much younger ages is yet to be determined. Techniques other than fMRI will be needed to evaluate whether the regions identified here show differences at much younger ages when early or late talker status can be directly observed. For example, structural differences in the regions identified might be evident early in life, or functional differences might be observed with techniques such as near infrared spectroscopy. Such data might serve to identify risk factors or predictors of poorer language and literacy outcomes.

One limitation of this investigation is the reliance on retrospective parent report. Although parent report of language development has been found to be quite reliable (Rescorla and Alley, 2001; Zubrick et al., 2007), the current study requires replication with a prospective cohort evaluated longitudinally from the onset of spoken language acquisition. Nonetheless, the persisting school-age differences in language and literacy in children with a history of late talking are consistent with prior research, and the neuroimaging findings offer a new description of underlying neural differences.

In summary, the current study provides behavioural evidence of consistently lower performance on language and literacy tasks of late talkers who are now in early elementary school, and consistently higher performance on these tasks for early talkers. Moreover, early spoken language development is related to processing of speech and print in several regions, including the striatum, thalamus, insula and superior temporal gyrus, providing an avenue for understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of the acquisition of oral language. These findings underscore the importance of early language development on the formation of critical language and reading circuits, and point to the need for early identification of delays in linguistic development.

Funding

National Institutes of Health grants awarded to Haskins Laboratories (T32HD7548 and 5P01HD001994) and to Yale University (5R01HD048830).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

References

- Alexander MP, Naeser MA, Palumbo CL. Correlations of subcortical CT lesion sites and aphasia profiles. Brain. 1987;110:961–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M, Geng JJ, Shomstein S. Parietal cortex and attention. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:212–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton E, Salmond CH, Watkins KE, Vargha-Khadem F, Gadian DG. Bilateral brain abnormalities associated with dominantly inherited verbal and orofacial dyspraxia. Human Brain Mapp. 2003;18:194–200. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JR, Wood L, Lu D, Houk JC, Bitan T. The role of the basal ganglia and cerebellum in language processing. Brain Res. 2007;1133:136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Frith CD. Differential activation of right superior parietal cortex and intraparietal sulcus by spatial and nonspatial attention. NeuroImage. 1998;82:176–87. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary MA, Anderson P. Speech and nonspeech motor performance in children with suspected dyspraxia of speech. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1990;12:63. [Google Scholar]

- De Diego-Balaguer R, Couette M, Dolbeau G, Durr A, Youssov K, Bachoud-Levi A-C. Striatal degeneration impairs language learning: evidence from Huntington's disease. Brain. 2008;131:2870–81. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M. Developmental plasticity in children: the role of biological risk, development, time, and reserve. J Commun Disord. 2000;33:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(00)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3rd. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Fossella J, Flombaum JI, Posner MI. The activation of attentional networks. NeuroImage. 2005;26:471–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Ashburner J, Frith CD, Poline JB, Heather JD, Frackowiak RSJ. Spatialregistration and normalization of images. Human Brain Mapp. 1995;2:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Frost SJ, Landi N, Mencl WE, Sandak R, Fulbright RK, Tejada ET, et al. Phonological awareness predicts activation patterns for print and speech. Ann Dyslexia. 2009;59:78–97. doi: 10.1007/s11881-009-0024-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauger LM, Lombardino LJ, Leonard CM. Brain morphology in children with specific language impairment. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40:1272. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4006.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda A, LoTurco J, Ramus F, Fitch R, Rosen G. From genes to behavior in developmental dyslexia. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1213–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda A, Sherman G, Rosen G. Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:222–33. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry RG, Berman JI, Nagarajan SS, Mukherjee P, Berger MS. Subcortical pathways serving cortical language sites: initial experience with diffusion tensor imaging fiber tracking combined with intraoperative language mapping. NeuroImage. 2004;21:616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugdahl K, Gundersen H, Brekke C, Thomsen T, Rimol LM, Ersland L, et al. fMRI Brain activation in a Finnish gamily with specific language impairment compared with a normal control group. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2004;47:162–72. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Hesselink JR, Sowell E, Tallal PA. Cerebral structure on magnetic resonance imaging in language- and learning-impaired children. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:539–45. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530170103028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketteler D, Kastrau F, Vohn R, Huber W. The subcortical role of language processing. High level linguistic features such as ambiguity-resolution and the human brain; an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2008;39:2002–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liegeois F, Baldeweg T, Connelly A, Gadian DG, Mishkin M, Vargha-Khadem F. Language fMRI abnormalities associated with FOXP2 gene mutation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JL. A theory of neurolinguistic development. Brain Lang. 1997;58:265–326. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen H, Ahonen T, Eklund K, Guttorm T, Kulju P, Laakso ML, et al. Early development of children at familial risk for dyslexia: follow-up from birth to school age. Dyslexia. 2004a;10:146–78. doi: 10.1002/dys.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen H, Aro M, Eklund K, Erskine J, Guttorm T, Laakso M-L, et al. The development of children at familial risk for dyslexia: birth to early school age. Ann Dyslexia. 2004b;54:184–220. doi: 10.1007/s11881-004-0010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen P, Poikkeus A-M, Laakso M-L, Eklund K, Lyytinen H. Language development and symbolic play in children with and without familial risk for dyslexia. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:873–85. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/070). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaburn E, Dale PS, Craig IW, Plomin R. Language-impaired children: No sign of the FOXP2 mutation. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1075–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200206120-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Murray C, Clancy K, Andrews D. Reading and metaphonological outcomes in late talkers. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40:1037–47. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4005.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett ER, Kuniholm E, Protopapas A, Friedman J, Lieberman P. Selective speech motor, syntax and cognitive deficits associated with bilateral damage to the putamen and the head of the caudate nucleus: a case study. Neuropsychologia. 1998;36:173–88. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(97)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante E, Swisher L, Vance R, Rapcsak S. MRI findings in boys with specific language impairment. Brain Lang. 1991;41:52–66. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(91)90110-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell RP, Bishop DVM. Clumsiness and perceptual problems in children with specific language impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:755–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Jenner AR, Katz L, Frost SJ, Lee JR, et al. Functional neuroimaging studies of reading and reading disability (developmental dyslexia) Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:207–13. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:3<207::AID-MRDD8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Jenner AR, Katz L, Frost SJ, Lee JR, et al. Neurobiological studies of reading and reading disability. J Commun Disord. 2001;34:479–92. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(01)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:360–71. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/028). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Age 13 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48:459–72. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Age 17 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers: Support for a dimensional perspective on language delay. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52:16–30. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0171). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L, Alley A. Validation of the language development survey (LDS): a parent report tool for identifying language delay in toddlers. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:434–45. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/035). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS. Very early language deficits in dyslexic children. Child Dev. 1990;61:1728–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS, Dobrich W. Development of children with early language delay. J Speech Hear Res. 1990;33:70–83. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3301.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML, Price CJ. Reading aloud boosts connectivity through the putamen. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:570–82. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard SE, Snowling MJ, Bishop DVM, Chipchase BB, Kaplan CA. Language-impaired preschoolers: a follow-up into adolescence. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1998;41:407–18. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4102.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettamanti MCA, Moro A, Messa C, Moresco RM, Rizzo G, Carpinelli A, et al. Basal ganglia and language: phonology modulates dopaminergic release. Neuroreport. 2005;16:397–401. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200503150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Test of word reading efficiency. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman MT, Pierpont EI. Specific language impairment is not specific to language: the procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex. 2005;41:399–433. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargha-Khadem F, Gadian DG, Copp A, Mishkin M. FOXP2 and the neuroanatomy of speech and language. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:131–8. doi: 10.1038/nrn1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargha-Khadem F, Watkins KE, Price CJ, Ashburner J, Alcock KJ, Connelly A, et al. Neural basis of an inherited speech and language disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12695–700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viholainen H, Ahonen T, Cantell M, Lyytinen P, Lyytinen H. Development of early motor skills and language in children at risk for familial dyslexia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:761–9. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RK, Torgesen JK, Rashotte CA. Comprehensive test of phonological processing. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Vargha-Khadem F, Ashburner J, Passingham RE, Connelly A, Friston KJ, et al. MRI analysis of an inherited speech and language disorder: structural brain abnormalities. Brain. 2002;125:465–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederholt JL, Bryant BR. Gray Oral Reading Test. 4. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wise RJ, Greene J, Buchel C, Scott SK. Brain regions involved in articulation. Lancet. 1999;353:1057–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff PH, Cohen C, Drake C. Impaired motor timing control in specific reading retardation. Neuropsychologia. 1984;22:587–600. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(84)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson Test of Achievement. III. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zubrick SR, Taylor CL, Rice ML, Slegers DW. Late language emergence at 24 months: An epidemiological study of prevalence, predictors, and covariates. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2007;50:1562–92. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2007/106). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.