Abstract

Although antibodies can be elicited by HIV-1 infection or immunization, those that are broadly neutralizing (bnAbs) are undetectable in most individuals, and when they do arise in HIV-1 infection, only do so years after transmission. Until recently, the reasons for difficulty in inducing such bnAbs have been obscure. Recent technological advances in isolating bnAbs from rare patients have increased our knowledge of their specificities and features, and along with gene-targeting studies, have also begun uncovering evidence of immunoregulatory roadblocks preventing their induction. One critical avenue towards developing an effective HIV-1 vaccine is to harness this emerging information into the rational design of immunogens and formulation of adjuvants, such that structural and immunological hurdles to routinely eliciting bnAbs can be overcome.

Introduction

One key correlate of protection in most effective FDA-approved vaccines is the generation of antibodies that inactivate or neutralize the infectious agent [1]. It is therefore widely held that the rapid elicitation of potent HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies systemically and at mucosal sites would be an important component of a preventive vaccine [2]. Furthermore, because HIV-1 is unlike many pathogens in that it is an integrating retrovirus and rapidly mutates [3,4] a truly efficacious vaccine would require broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) i.e. those that can protect against a wide array of HIV-1 strains [5,6]. Indeed, passive administration of rare bnAbs (infused as mAbs at physiologically-relevant titers) in non-human primates has demonstrated their ability to completely protect from HIV-1 challenge [7–10]. Thus, defining impediments to their routine induction is critical to successful HIV-1 vaccine development.

Many reasons for the rarity of bnAbs have been proposed, mostly relating to the unusual features of the HIV-1 Envelope (Env) [11]. These include the Env’s predilection for forming an extensive glycan “shield” [3,4,12], rapid neutralizing Ab selection of escape mutants [3,4], transient epitope expression [13], steric hindrance [14,15], and inability to overcome Ab-binding entropic barriers [16]. Another potential reason is that highly immunogenic epitopes present on non-native Env structures may hinder bnAb responses by instead inducing dominant Ab responses that are non-neutralizing or are neutralizing, but strain-specific [11,17]. Recent studies have found that ~20% of infected persons will develop a degree of neutralization breadth, raising hope that induction of these Abs will not be as difficult as originally thought [17,18].

An additional hypothesis for the difficulty in induction of bnAbs has been proposed, based on the observation that certain bnAbs were found to exhibit polyreactivity [19]. This hypothesis postulates that such Abs cannot be made because the B cells from which they originate are sufficiently autoreactive to trigger tolerance mechanisms that eliminate or modify bnAb self-reactivity [20]. In this review, we highlight recent studies that provide evidence for immunoregulation in limiting the expression of certain bnAbs and discuss unusual features common to all bnAbs.

Specificities and traits of bnAbs

Five human bnAbs, 2F5, 4E10, 2G12, b12 and Z13, were initially isolated from HIV-1 infected subjects, and represented the prototypic protective antibodies an HIV-1 vaccine should elicit [21–25]. With the advent of high throughput recombinant Ab technology, many new bnAbs have now been identified, some with higher potency than those of the first generation [26–31]. The rate of bnAb discovery, combined with a body of work over the last decade in characterizing the five original bnAbs, has resulted in two significant advances. First, four distinct Env regions have been identified, each representing a potential Achilles’ heel for HIV-1 that could be targeted by an antibody-based vaccine: the gp41 Membrane Proximal External Region (MPER), the gp120 CD4 binding site, quaternary V2/V3 loop epitopes, and Env carbohydrates (reviewed in [11]). Second, these studies have revealed an interesting pattern in which all bnAbs share at least one of the following three unusual characteristics: a) self-/polyreactivity, b) elongated, and highly hydrophobic (and/or charged) heavy chain complementary determining regions (HCDR3), and c) high numbers of Ig somatic mutations ([11];Table 1). These bnAb traits will be discussed in terms of clues they are providing about potential mechanisms controlling bnAb induction, as well as their relevance to bnAb specificity and neutralization potential.

Table 1.

Immunogenetic and functional characteristics of representative bnAbs

| bnAba | Env epitope specificity |

Neutralizationb | Isotype | V family usage | % VH mutationsd |

HCDR3 featurese | Polyreactivity | Original ref. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breadth | Potency | VH | Vκ/Vλ | length | #pos. charges |

avg. hydrop. |

||||||

| 2F5 | gp41 MPER | 60 | 2.3 | IgG3 | 2–5 | κ1–13 | 15.2 | 24 | 3 | −0.04 | Yes | [22] |

| 4E10 | gp41 MPER | 98 | 3.2 | IgG3 | 1–69 | κ3–20 | 15.6 | 20 | 3 | −0.27 | Yes | [23] |

| M66.6 | gp41 MPER | 25 | 18.0 | IgG1c | 5–51 | κ1–39 | 9.3 | 23 | 2 | −0.89 | Yes | [31] |

| 2G12 | gp120 glycan shield | 32 | 2.4 | IgG1 | 3–21 | κ1–5 | 31.7 | 16 | 3 | −1.5 | Yes | [24] |

| 1b12 | gp120 CD4 binding site | 41 | 1.8 | IgG1c | 1–3 | κ3–20 | 13.1 | 20 | 1 | −1.2 | Yes | [21] |

| VRC01,VRC02 | gp120 CD4 binding site | 91 | 0.34,0.32 | IgG1c | 1–2 | κ3–11 | 32.1 | 14 | 3 | −1.9 | No | [29••] |

| VRC03 | gp120 CD4 binding site | 57 | 0.45 | IgG1c | 1–2 | κ3–20 | 30.2 | 16 | 2 | −0.89 | No | [29••] |

| HJ16 | gp120 CD4 DMR core | 36 | 8.0 | IgG1c | 3–3 | κ4–1 | 14.6 | 21 | NDf | ND | ND | [27] |

| PG9,PG16 | gp120 quaternary V2,V3 | 79,73 | 0.22,0.15 | IgG1c | 3–33 | λ2–14 | 16.7, 20.5 | 30 | 2,3 | −1.4,−1.1 | No | [28••] |

| CH01–CH04 | gp120 quaternary V2,V3 | 35–45 | 0.46–1.1 | IgG1c | 3–20 | κ3–20 | 11.5–14.3 | 24 | 1,1,1,0 | −0.4,.8,.4,.7 | Yes, except CH04 | [26] |

| CH05 | gp120 quaternary V2,V3 | 44 | 0.79 | IgG1c | 3–20 | κ1–6 | 11.5 | 24 | 0 | −0.7 | No | [26] |

bnAbs listed in the same row are somatic variants of the same clone, those shaded represent a likely clonally-related lineage.

breadth is defined as the percent of primary isolates neutralized with an IC50<50 µg/ml; potency is defined as the mean IC50 value (µg/ml) within the group of viruses neutralized with IC50 values <50 µg/ml.

IgG1 vector construct; original isotype not reported/not determined.

estimate based on aa sequence comparisons of original (mutated) and inferred reverted (unmutated) V(D)J rearrangements.

average hydrophobicity (GRAVY) values of HCDR3 aa were determined using the Duke University Laboratory for Computational Immunology’s SoDA program; for reference, mean HCDR3 aa length and number of positive charges in the normal mature naïve human B cell repertoire are 13.5, and 0.67, respectively [34].

ND=not determined

Relationship of bnAb traits to selection checkpoints during normal B cell ontogeny

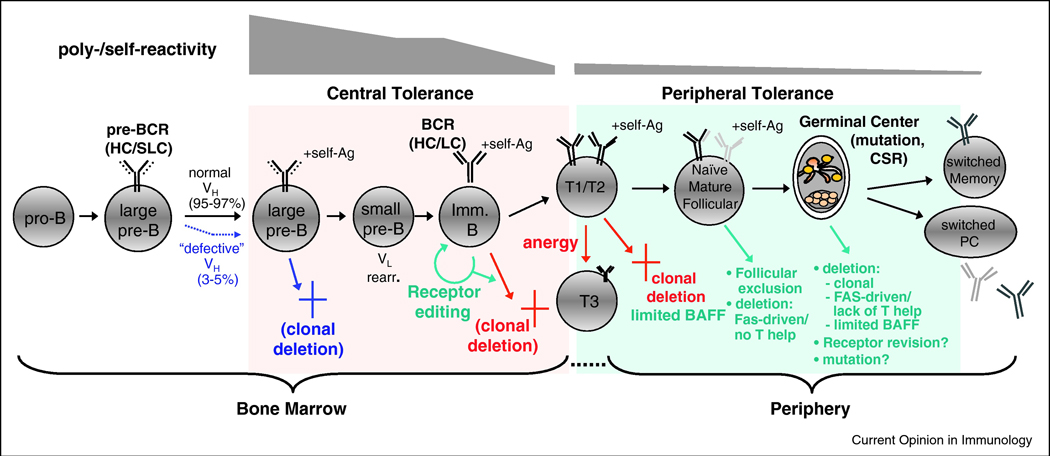

There is compelling evidence that Abs with self-/polyreactivity are closely associated with negative selection of the B cells expressing them [32,33]. Early studies in mice clearly demonstrated that removal of self-reactivity occurs via three major mechanisms: deletion, anergy, and receptor editing, at several distinct developmental checkpoints. Studies measuring polyreactivity of Abs sampled from the normal human B cell repertoire have closely mirrored studies of self-reactivity, demonstrating that analogous tolerance mechanisms are associated with reduction of the pre-selected, immature repertoire’s enriched polyreactivity from ~55–75% to ~5% in the post-selected, mature B cell repertoire [34].

Another set of bnAb traits, i.e. elongated, hydrophobic, and/or charged HCDR3s residues, appear more prevalent in the immature IgM+IgD- B cell repertoire of both mouse and man [34–37], and are thus considered potential predictors of negative selection for B cells bearing them. The role of tolerance in removing B cells bearing positively charged residues in HCDRs is best demonstrated in vivo in the 3H9 HC series of anti-DNA transgenic mice, where arginine residues qualitatively impact tolerance outcome: an increasing number of arginines in CDRs is accompanied by increased affinity for DNA and triggering of central deletion that is largely independent of LC pairing [38–40]. The mechanisms responsible for counterselecting B cells bearing elongated, hydrophobic HCDR3s are less clear, but deletion or editing of immature IgM+IgD- B cells bearing long HCDR3s has been noted [36]. Of note, B cells bearing elongated and/or unusually charged HCDR3s may be subjected to negative selection even earlier in B cell development. The mechanisms for this remain controversial and may involve clonal deletion by pre-BCR-mediated signals and/or defective pairing of HCs with surrogate light chain (SLC) [41–44]. The latter process, however, is critical in allowing B cells bearing particular VH genes i.e. VH81X, to efficiently progress in development [45–47].

Evidence for tolerance mechanisms limiting bnAbs with self-reactive traits

Evidence that B cells expressing bnAbs with self-reactivity are under tolerance controls comes from a series of 2F5 knock-in (KI) mouse lines, made by targeted insertion of the original VL and/or VH rearrangements of 2F5, an MPER-specific bnAb with a long, charged, hydrophobic HCDR3, and reactive with HEp-2 cells and several self-antigens including cardiolipin, PS, and histones [19]. In 2F5 VH KI mice, expression of the 2F5 HC alone is sufficient to trigger profound central tolerance [48], reminiscent of prior KI/tg models expressing HCs with “dominant” self-reactivities, such as those specific for DNA, MHC-I, or red blood cells [49]. While the main developmental blockade in these mice is associated with deletion at the pre-B to immature transition, characteristics of residual 2F5 HC-expressing B cells and serum Ig suggest they are under additional tolerance controls, including anergy [48]. Importantly, in 2F5 VH×VL KI mice, B cells expressing the original 2F5 VH/VL pair are even more efficiently deleted, demonstrating that the 2F5 LC contributes to this tolerization [50].

A distinct VH KI line, made from another MPER-specific bnAb, 4E10, has identified a developmental blockade similar to that seen in 2F5 VH KI mice, indicating that self-reactivity of 4E10 is also sufficient to induce central deletion of most 4E10 VH-bearing B cells [51]. Additionally, a study using B-cell tetramers to track the frequencies of developing B cell subsets from the normal C57BL/6 repertoire, also showed a developmentally regulated reduction in B cells specifically recognizing the same nominal epitope recognized by 2F5 [52]. Taken together, these data suggest that many MPER-specific bnAbs are subjected to tolerance controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A corollary to the hypothesis that poly-/self-reactive bnAbs are not routinely made due to tolerization of their B cells, is that they can be made in situations where tolerization is either mitigated or absent. Indeed, a possible clinical correlate supporting this is a lower-than-expected reporting rate of coincident HIV-1 and SLE disease [53–55]. Also, studies of the 2F5 bnAb and its specific nominal MPER epitope support the notion that self-reactive bnAb-specific B cells are enriched when tolerance controls are removed. This is seen in the case of autoimmune-prone mice [56], and in mice reconstituted with B cells developed in vitro under conditions permissive for self-reactivity, wherein an enrichment for MPER-specific B cells is accompanied by robust anti-MPER responses to immunization with MPER peptides [52,57]. Finally, B cells from 2F5 VH×VL KI bone marrow that are normally deleted in vivo, can be rescued by in vitro culture and immortalized as hybridomas which display the same reactivity and neutralizing properties of 2F5 [51].

Functional relevance of bnAb traits to HIV-1 binding and neutralization

Polyreactivity in bnAbs appears to be functionally relevant in at least two regards. First, a bnAbs’s given spectrum of polyreactivity may be required for its functional specificity, for example the lipid polyreactivity of the MPER-specific bnAbs 2F5 and 4E10 is critical for their mechanism of neutralization [58–60]. Second, general polyreactivity has been proposed to increase the probability of bivalent binding by anti-Env antibodies to HIV virions [61]. Extensive HIV-induced polyreactivity (70% of mAbs isolated) was shown to enhance the avidity of anti-Env antibodies by facilitating heteroligation, i.e., bivalent antibody binding involving distinct Env-specific and non-Env (virion/host) components [62]. An analogous mechanism was reported for a polyreactive CD4-inducible antibody, 21c, in which an adjacent bound CD4 receptor is used as part of the CD4i epitope [63].

With respect to the unusual length, hydrophobicity, and charge of bnAb HCDR3s, hydrophobic HCDR3 residues in MPER-specific bnAbs are thought to be critical for lipid reactivity that permits subsequent binding with the exposed MPER epitope and both events are critical for neutralization [58,64]. Positively charged HCDR3 residues are critical for 2F5’s interactions with the MPER epitope [65,66], but not necessarily 4E10’s [67].

Finally, it is not known why most bnAbs have an unusually high frequency of somatic mutations, although two related possibilities in the context of HIV-1 hyperactivation/GC dysregulation is either aberrant regulation of the somatic mutation machinery or defective selection of B cells undergoing affinity maturation. Understanding these mechanisms during the course of HIV-1 infection, as well as performing Env immunization studies in KI models of reverted (unmutated) bnAbs, will be critical in ascertaining how affinity maturation impacts acquisition of broad neutralizing function.

Challenges faced and lessons to be learned

In designing strategies to elicit self-reactive bnAbs, three questions emerge from the above studies: 1) are all bnAbs with self-/polyreactive traits (including those that don’t target the MPER), also subjected to tolerance controls? 2) what percentage of bnAbs have or had such traits at some point of their maturational pathway; and, 3) in terms of bnAb structure-function correlates, does bnAb tolerizing self-reactivity overlap with binding required for neutralization?

The existence of non-autoreactive bnAbs such as VRC01, with an unremarkable HCDR3, but with an extremely high rate of somatic mutations suggests that a valid vaccination strategy would need to focus drive a prolonged maturation process to elicit these kinds of bnAbs. Certainly, not all polyreactive B cells are subjected to tolerance controls and not all B-cell clones normally subjected to tolerance controls produce pathogenic antibodies. In the case of the gp41 MPER-specific bnAbs 2F5 and 4E10, their passive infusion in humans has not been associated with pathogenicity [68], although in neonatal infant macaques, a possible bleeding event was seen [69]. Assuming pathogenicity is not a general problem of MPER-specific bnAbs, M66 and 4E10 could be two attractive self-/polyreactive bnAb candidates to elicit, because they have relatively low frequencies of Ig somatic mutations (Table 1) and may recognize less complex and restrictive Env epitopes [70]. Related to this issue, bnAbs like 4E10 may have the additional advantage of using functionally conserved VH genes i.e. used in multiple viral responses and well represented in the nascent B cell repertoire; indeed, the VH1–69 gene used by 4E10 is common to many Abs against hepatitis C and influenza [71].

In understanding the relative importance for immunization approaches to induce epitope specificity and polyreactivity for the neutralizing function of MPER-targeted Abs, recent studies have provided interesting, initial clues. Dennison et al. have shown that many gp41-specific mAbs are lipid reactive but do not neutralize HIV-1 because they bind to non-neutralizing gp41 epitopes [72]. Thus, for these types of Abs, lipid reactivity is necessary but not sufficient for neutralization. Moreover, Guenaga et al. [73] and Dennison and colleagues [74] have used immunization strategies with scaffolds as well as heterologous prime-boosts to focus the Ab response on the nominal gp41 MPER neutralizing epitope (664DKW) that is recognized by 2F5 [59,65]. However, in both instances, Abs did not neutralize HIV-1, and in the Dennison et al. study [74], the induced 664DKW Abs were not polyreactive with lipids. Thus, for eliciting 2F5-like bnAbs, i.e. directed at the nominal 2F5 neutralizing epitope, it appears that induction of polyreactive Abs that bind this epitope and virion lipids is critical for efficient HIV-1 neutralization, and it is these types of Abs that are regulated most stringently.

Conclusions

The pace at which novel HIV bnAbs have been identified and characterized has provided new insight into the traits of HIV-1 bnAbs, and has now positioned the field to determine the critical requirements for broad and potent HIV-1 antibody induction. Ongoing studies will establish what bnAb traits are relevant for bnAb regulation and function, and secondly, will provide a much deeper understanding of the basic B cell biology regarding how bnAbs are generated, the B cell subsets they originated from, the relevant checkpoints during their ontogeny, and how somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation impact Ab function. This information should provide guidance for immunogen/adjuvant based strategies aimed at targeting relevant B cell populations and stimulating B cell diversification processes, thus optimizing the possibility that relevant bnAb functional specificities can be safely induced.

The main hurdle in developing a protective Ab-based HIV-1 vaccine continues to be the inability of current vaccination strategies to induce effective bnAb responses (i.e. those that are high titered and long lasting). The key remaining gaps in knowledge that future studies need to address include comprehensively establishing which traits in bnAbs are most relevant for their functions and in vivo regulation, developing a much deeper understanding of the ontogeny of bnAbs, including defining the precursor B cell subsets from which bnAbs originate, defining the relevant checkpoints bNabs are under, and understanding how somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation impact acquisition of bnAb functional properties. Another perhaps equally important consideration is defining the mechanisms that drive existing/current Env immunogens to elicit dominant non-neutralizing responses that may hinder the induction of bnAb responses. Thus, future studies should be aimed at defining the specific Env structures and/or residues required for naïve B cell activation, the host genetic factors that regulate bnAb induction, and the B cell maturation pathways that lead to bnAb responses.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by a Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation and National Institutes of Health grants AI0678501, AI081579, and AI087202.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(7):1055–1065. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMichael AJ, Borrow S, Tomaras GD, Goonetilleke N, Haynes BF. The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: Clues for vaccine development. Nature Rev Immunol. 2010;10:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to hiv type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422(6929):307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG, Sun C, Grayson T, Wang S, Li H, Wei X, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(21):7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. The role of antibodies in HIV vaccines. Annual Rev Immunol. 2010;28:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal shiv challenge in macaques. Nature Medicine. 2009;15(8):951–954. doi: 10.1038/nm.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Poignard P, Hangartner L, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Watkins DI, Burton DR. Broadly neutralizing human anti-hiv antibody 2G12 is effective in protection against mucosal SHIV challenge even at low serum neutralizing titers. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433. e1000433. Key paper showing that the broadly neutralizing antibody 2G12 can protect rhesus macaques at much lower levels of serum antibody that previously thought.

- 9.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Tehrani DM, Huber M, Weisgrau KL, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Poignard P, Watkins DI, Burton DR. Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 directed against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region protect against mucosal challenge by simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV ba-L. J Virol. 2010;84(3):1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel SS, Birx DL, Lewis MG. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2000;6(2):207–210. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McElrath MJ, Haynes BF. Induction of immunity to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 by vaccination. Immunity. 2010;33:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.011. Recent review that discusses all aspects of HIV-1 vaccine development but in particular covers many aspects of the search for methods to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 Env.

- 12.Binley JM, Ban YE, Crooks ET, Eggink D, Osawa K, Schief WR, Sanders RW. Role of complex carbohydrates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and resistance to antibody neutralization. J Virol. 2010;84(11):5637–5655. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00105-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey G, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Morelli M, Cheng Y, Chen B. A fusion-intermediate state of HIV-1 gp41 targeted by broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800255105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labrijn AF, Poignard P, Raja A, Zwick MB, Delgado K, Franti M, Binley JM, Vivona V, Grundner C, Huang CC, Venturi M, et al. Access of antibody molecules to the conserved coreceptor binding site on glycoprotein gp120 is sterically restricted on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2003;77(19):10557–10565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10557-10565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schief WR, Ban YE, Stamatatos L. Challenges for structure-based HIV vaccine design. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(5):431–440. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832e6184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, Katinger H, et al. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature. 2002;420(6916):678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. Neutralizing antibodies generated during natural HIV-1 infection: Good news for an HIV-1 vaccine? Nat Medicine. 2009;15(8):866–870. doi: 10.1038/nm.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mikell I, Sather DN, Kalams SA, Altfeld M, Alter G, Stamatatos L. Characteristics of the earliest cross-neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001251. e1001251. This study comprehensively profiles neutralization breadth and Env-specificity of Ab responses in early and late stages of HIV infection. Surprisingly, a high percentage (~25%) of infected subjects can make delayed neutralizing Ab responses that reach significant breadth (>50%) and are predominantly focused to the CD4 binding site. In contrast, subjects only capable of eliciting non-neutralizing responses show specificity for non-native (monomeric) Env structures.

- 19.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, Ortel TL, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308(5730):1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes BF, Moody MA, Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Alam SM. Antibody polyspecificity and neutralization of HIV-1: A hypothesis. Hum Antibodies. 2005;14(3–4):59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton DR, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp SJ, Thornton GB, Parren PW, Sawyer LS, Hendry RM, Dunlop N, Nara PL, et al. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266(5187):1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67(11):6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stiegler G, Kunert R, Purtscher M, Wolbank S, Voglauer R, Steindl F, Katinger H. A potent cross-clade neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against a novel epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17(18):1757–1765. doi: 10.1089/08892220152741450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore JP, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70(2):1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwick MB, Labrijn AF, Wang M, Spenlehauer C, Saphire EO, Binley JM, Moore JP, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Burton DR, Parren PW. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J Virol. 2001;75(22):10892–10905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10892-10905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonsignori M, Hwang K-K, Chen X, Tsao C-Y, Bilska M, Fang W, Marshall D, Whitesides JF, Crump JA, Noel S, Kapiga S, et al. Immunoregulation of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody responses: Deciphering maturation paths for antibody induction. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26:A-4.52. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corti D, Langedijk JP, Hinz A, Seaman MS, Vanzetta F, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Silacci C, Pinna D, Jarrossay D, Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh S, Willems B, et al. Analysis of memory B cell responses and isolation of novel monoclonal antibodies with neutralizing breadth from HIV-1-infected individuals. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an african donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326(5950):285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. This recent paper describes the quaternary broad neutralizing antibodies PG9 and PG16 that bnd to conformational V2,V3 epitope on gp120 and constitute a new target for HIV-1 vaccine development.

- 29. Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, et al. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329(5993):856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. A recent key study reporting the broadest neutralizing antibody to date (VRC01) isolated by single memory B cell sorting.

- 30.Zhou T, Georgiev I, Wu X, Z.Y. Y, Dai K, A. F, Kwon YD, Scheid JF, Shi W, Xu L, Yang Y, et al. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329(5993):811–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Z, Qin H, Chen W, Zhao Q, Fouda G, Schutte R, Shen X, Liao L, Ofek G, Owens J, Streaker E, et al. New broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies targeting the 2F5 epitope. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(10):A-5.4. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basten A, Silveira PA. B-cell tolerance: Mechanisms and implications. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(5):566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meffre E, Wardemann H. B-cell tolerance checkpoints in health and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(6):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301(5638):1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanov II, Schelonka RL, Zhuang Y, Gartland GL, Zemlin M, Schroeder HW., Jr Development of the expressed Ig CDR-H3 repertoire is marked by focusing of constraints in length, amino acid use, and charge that re first established in early B cell progenitors. J Immunol. 2005;174:7773–7780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meffre E, Milili M, Blanco-Betancourt C, Antunes H, Nussenzweig MC, Schiff C. Immunoglobulin heavy chain expression shapes the B cell receptor repertoire in human B cell development. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(6):879–886. doi: 10.1172/JCI13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiokawa S, Mortari F, Lima J, Nuñez C, Bertrand Fr, Kirkham PM, Zhu S, Dasanayake AP, Schroeder HJ. IgM heavy chain complementarity-determining region 3 diversity is constrained by genetic and somatic mechanisms until two months after birth. J Immunol. 1999;162(10):6060–6070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Jiang Y, Prak EL, Radic M, Weigert M. Editors and editing of anti-DNA receptors. Immunity. 2001;15:947–957. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Nagy Z, Radic MZ, Hardy RR, Huszar D, Camper SA, Weigert M. The site and stage of anti-DNA B-cell deletion. Nature. 1995;373(6511):252–255. doi: 10.1038/373252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C, Prak EL, Weigert M. Editing disease-associated autoantibodies. Immunity. 1997;6:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardy RR. B-1 B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177(5):2749–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keenan RA, De Riva A, Corleis B, Hepburn L, Licence S, Winkler TH, Mårtensson IL. Censoring of autoreactive b cell development by the pre-B cell receptor. Science. 2008;321(5889):696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.1157533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vettermann C, Jäck HM. The pre-B cell receptor: Turning autoreactivity into self-defense. Trends Immunol. 2010;31(5):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Boehmer H, Melchers F. Checkpoints in lymphocyte development and autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(1):14–20. doi: 10.1038/ni.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Decker DJ, Kline GH, Hayden TA, Zaharevitz SN, Klinman NR. Heavy chain V gene-specific elimination of B cells during the pre-B cell to B cell transition. J Immunol. 1995;154(10):4924–4935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kline GH, Hartwell L, Beck-Engeser GB, Keyna U, Zaharevitz S, Klinman NR, Jäck HM. Pre-B cell receptor-mediated selection of pre-B cells synthesizing functional mu heavy chains. J Immunol. 1998;161(4):1608–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(5):323–335. doi: 10.1038/nri799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verkoczy L, Diaz M, Holl TM, Ouyang YB, Bouton-Verville H, Alam SM, Liao HX, Kelsoe G, Haynes BF. Autoreactivity in an HIV-1 broadly reactive neutralizing antibody variable region heavy chain induces immunologic tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(1):181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912914107. The first paper to report a knock-in mouse model for a HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody. This study demonstrates that most B cells from a targeted transgenic line carrying the original 2F5 HC V(D)J rearrangement undergo central deletion in vivo and suggests that additional tolerance controls regulate 2F5 VH-expressing B cells in the periphery.

- 49.Shlomchik MJ. Sites and stages of autoreactive B cell activation and regulation. Immunity. 2008;28(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verkoczy L, Bouton-Verville H, Hutchinson J, Scearce RM, Liao H-X, Hwang K-K, Haynes BF. Role of immunoglobulin light chain usage and MPER specificity in counterselecting B cells expressing the broadly neutralizing antibody 2F5. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(10):A-4.55. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verkoczy L, Chen Y, Bouton-Verville H, Hutchinson J, Scearce RM, Holl TM, Hwang K-K, Kelsoe G, Haynes BF. Clonal deletion of MPER antibodies: Implications for vaccine design. 18th CROI: Anti-HIV symposium. 2011:A-63. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holl TM, Kuraoka M, Liao D, Verkoczy L, Moody MA, Alam M, Liao HX, Haynes BF, G.H. K. Generation of antibody responses to HIV-1 membrane proximal external region (MPER) antigen. Retrovirology. 2009;6(3):A-4.26. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaye BR. Rheumatologic manifestations of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(2):158–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-2-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palacios R, Santos J. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(4):277–278. doi: 10.1258/095646204773557857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palacios R, Santos J, Valdivielso P, Márquez M. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and systemic lupus erythematosus. An unusual case and a review of the literature. Lupus. 2002;11(1):60–63. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu141cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verkoczy L, Moody MA, Holl TM, Bouton-Verville H, Scearce R, Hutchinson J, Alam SM, Kelsoe G, Haynes B. Functional, non-clonal IgMa-restricted B cell receptor interactions with the HIV-1 envelope gp41 membrane proximal external region. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holl TM, Haynes BF, Kelsoe G. Stromal cell independent B cell development in vitro: Generation and recovery of autoreactive clones. J Immunol Methods. 2010;354(1–2):53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alam SM, Morelli M, Dennison SM, Liao HX, Zhang R, Xia SM, Rits-Volloch S, Sun L, Harrison SC, Haynes BF, Chen B. Role of HIV membrane in neutralization by two broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(48):20234–20239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908713106. The first in a series of recent papers demonstrating that the hydrophobic HCDR3 loop of the MPER-specific bnAbs 2F5 and 4E10 is a critical feature for their initial attachment to the viral membrane and thus their ability to neutralize, but not for contacting the MPER pre-hairpin intermediate. These results also further support the “two-step” binding model of HIV-1 neutralization by MPER-specific bnAbs.

- 59.Ofek G, McKee K, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Skinner J, Guenaga FJ, Wyatt R, Zwick MB, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Relationship between antibody 2F5 neutralization of HIV-1 and hydrophobicity of its heavy chain third complementarity-determining region. J Virol. 2010;84(6):2955–2962. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02257-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scherer EM, Leaman DP, Zwick MB, McMichael AJ, Burton DR. Aromatic residues at the edge of the antibody combining site facilitate viral glycoprotein recognition through membrane interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(4):1529–1534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909680107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein JS, Bjorkman PJ. Few and far between: How HIV may be evading antibody avidity. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000908. e1000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mouquet H, Scheid JF, Zoller MJ, Krogsgaard M, Ott RG, Shukair S, Artyomov MN, Pietzsch J, Connors M, Pereyra F, Walker BD, et al. Polyreactivity increases the apparent affinity of anti-HIV antibodies by heteroligation. Nature. 2010;467(7315):591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature09385. These authors tested both HIV-1 and non-HIV-1 reactivities of recombinant Abs derived from Env-specific naïve and memory B cells of rare infected patients (i.e. having bnAb serum responses), and surprisingly, found that the majority (75%) were polyreactive. As shown by surface plasmon resonance analysis, such Abs are capable of "heteroligation" between Env-specific and non- Env components, and their polyreactivity has been proposed as an important, general feature which enables Ab recognition of the low density of trimer spikes found on HIV-1 virions.

- 63. Diskin R, Marcovecchio PM, Bjorkman PJ. Structure of a Clade C HIV-1 gp120 bound to CD4 and CD4-induced antibody reveals anti-CD4 polyreactivity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(5):608–613. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1796. In this elegant study, the authors present a crystal structure of HIV-1 Clade C envelope with a CD4-induced Ab called 21c, and demonstrate that it not only binds to gp120, its expected (non-self) antigenic target, but surprisingly also contacts CD4 itself. Based on this unusual, polyreactive interaction of 21c, and again considering HIV spike structure, these investigators propose a model for facilitating 21c recognition of HIV-1, analogous to that for the previous reference.

- 64.Sun Z-Y, Oh KG, Kim M, Yu J, Brusic V, Song L, Qiao X, Wang JH, Wagner G, Reinherz EL. HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody extracts its epitope from a kinked mper segment on the viral membrane. Immunity. 2008;28(1):52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10724–10737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zwick MB, Komori HK, Stanfield RL, Church S, Wang M, Parren PW, Kunert R, Katinger H, Wilson IA, Burton DR. The long third complementarity-determining region of the heavy chain is important in the activity of the broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5. J Virol. 2004;78(6):3155–3161. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3155-3161.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cardoso RM, Zwick MB, Stanfield RL, Kunert R, Binley JM, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody 4E10 recognizes a helical conformation of a highly conserved fusion-associated motif in gp41. Immunity. 2005;22(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trkola A, Kuster H, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Leemann C, Manrique A, Huber M, Rehr M, Oxenius A, Weber R, et al. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2005;11(6):615–622. doi: 10.1038/nm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferrantelli F, Buckley KA, Rasmussen RA, Chalmers A, Wang T, Li PL, Williams AL, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Montefiori DC, Cavacini LA, Katinger H, et al. Time dependence of protective post-exposure prophylaxis with human monoclonal antibodies against pathogenic SHIV challenge in newborn macaques. Virology. 2007;358(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montero M, van Houten NE, Wang X, Scott JK. The membrane-proximal external region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: Dominant site of antibody neutralization and target for vaccine design. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2008;72(1):54–84. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lerner RA. Rare antibodies from combinatorial libraries suggests an S.O.S. Component of the human immunological repertoire. Mol Biosyst. 2011 Feb 4; doi: 10.1039/c0mb00310g. [Epub ahead of print]( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dennison SM, Anasti K, Scearce RM, Sutherland L, Parks R, Xia SM, Liao HX, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Haynes BF, Alam SM. Nonneutralizing HIV-1 gp41 envelope cluster II human monoclonal antibodies show polyreactivity for binding to phospholipids and protein autoantigens. J Virol. 2011;85(3):1340–1347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01680-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guenaga J, Dosenovic P, Ofek G, Baker D, Schief WR, Kwong PD, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Wyatt RT. Heterologous epitope-scaffold prime: boosting immuno-focuses B cell responses to the HIV-1 gp41 2F5 neutralization determinant. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dennison SM, Jaeger F, Anasti K, Sutherland L, Bowman C, Parks R, Santra S, Shen S, Tomaras G, Montefiori D, Letvin N, et al. Induction of antibodies with specificity for gp41 neutralizing epitopes by membrane anchored gp41 immunogens. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(10):A-5.10. [Google Scholar]