Abstract

Neovascularization is an early and critical step in tumor development and progression. Tumor vessels are distinct from their normal counterparts morphologically as well as at a molecular level. Recent studies on factors involved in tumor vascular development have identified new therapeutic targets for inhibiting tumor neovascularization and thus tumor progression. However, the process of tumor blood vessel formation is complex, and each tumor exhibits unique features in its vasculature. An understanding of the relative contribution of various pathways in the development of tumor vasculature is critical for developing effective and selective therapeutic approaches. Several such agents are currently in clinical trials, and many others are under development. In this review, the mechanisms and factors involved in tumor blood vessel formation are discussed. In addition, selected novel classes of antivascular therapies, including those targeting tumor endothelial cells and other components of the tumor vasculature, are summarized.

Introduction

The continuous growth of tumors and the development of metastases are inherently dependent on the development of an adequate vascular supply: angiogenesis [1]. It is widely thought that most tumors and metastases begin as avascular masses and require the formation of new vessels to grow beyond 1 mm in size [1,2]. The initiation of angiogenesis, the “angiogenic switch,” involves an alteration in the balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic molecules and is an early and essential event in tumor progression (Table 1) [3••]. Angiogenesis occurs when the balance between the activators and inhibitors of angiogenesis tips in favor of pro-angiogenic factors. During normal conditions, the vasculature is usually quiescent, with endothelial cell turnover occurring over years in tissues that do not require ongoing angiogenesis [4]. Even during conditions that do require physiologic angiogenesis, there is tight regulation of pro- and anti-angiogenic signals. In contrast, this balance is lost during carcinogenesis, and tumor blood vessels undergo constant turnover, enabling the continuous growth of new tumor blood vessels.

Table 1. Regulators of angiogenesis: pro- and anti-angiogenic molecules*.

| Activators | Inhibitors |

|---|---|

| VEGF/VEGFR | Thrombospondin-1 |

| FGF/FGFR | Angiostatin |

| PDGF/PDGFR | Endostatin |

| VE-cadherin | Interferon |

| MMPs | IL-12 |

| Ephrins/Eph | TIMPs |

| COX-2 | Dopamine |

| Angiopoietin 1 and 2 | |

| HIF1α |

This list includes some of the factors that are involved in the regulation of angiogenesis and is not meant to be comprehensive.

COX—cyclooxygenase; FGF—fibroblast growth factor; IL—interleukin; MMP—matrix metalloproteinase; PDGF—platelet-derived growth factor; R—receptor; TIMP—tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases; VEGF—vascular endothelial growth factor.

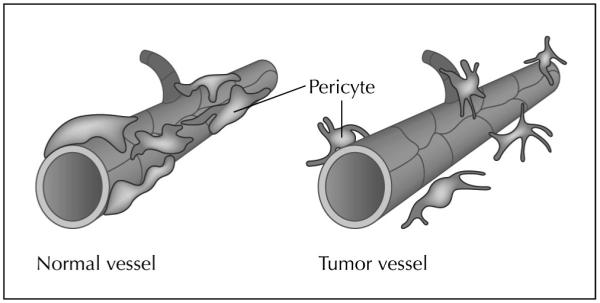

Tumor blood vessels are morphologically distinct from their normal counterparts. They are irregularly shaped, dilated, and tortuous [3••]. The vascular network that develops in tumors is often leaky and hemorrhagic, which is in part due to overproduction of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [5]. In addition, the vessel walls are thin, probably due to abnormalities in pericytes and other supporting cells (Fig. 1) [6]. Anti-angiogenesis therapies are based in part on the premise that tumor-associated endothelial cells are genetically normal and stable despite being phenotypically and functionally abnormal. Recently, this view has been challenged by two provocative papers, which suggest that tumor-associated endothelial cells may also harbor genetic abnormalities at a molecular level [7,8]. The comparison of gene expression patterns of normal and tumor-associated endothelial cells from colorectal tissues shows divergent patterns of expression, highlighting the molecular differences between these cells [7]. These studies demonstrate that tumor and normal endothelium are distinct at the molecular level, a finding that may have significant implications for the development of anti-angiogenic therapies. In addition, mouse endothelial cells from human xenografts of melanoma and liposarcoma display cytogenetic abnormalities with varying degrees of aneuploidy on fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis, which are absent in normal endothelial cells [8]. However, the clinical and biologic significance of these findings is not clearly understood.

Figure 1.

Structural alterations in tumor vasculature are depicted. Mature blood vessels have endothelial cells with tight gap junctions and uniform pericyte coverage (left). Tumor blood vessels are leaky (right). Although pericytes are present, they are poorly attached to the endothelial cells and have processes projecting toward the abluminal surface or into the tumor stroma.

Despite the progress in understanding neovascularization of tumors over the past 35 years, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Recent studies demonstrate the complexity of blood vessels in tumors. Formation of tumor vasculature is likely to involve multiple pathways. Angiogenesis can occur either by sprouting or by nonsprouting processes [9]. Sprouting angiogenesis occurs by branching (true sprouting) of new capillaries from preexisting vessels. Nonsprouting angiogenesis results from enlargement, splitting, and fusion of preexisting vessels produced by proliferation of endothelial cells within the wall of a vessel. Circulating endothelial precursors, shed from the vessel wall or mobilized from the bone marrow, can also contribute to tumor vascularization by a process known as vasculogenesis [10]. An additional mechanism involved in generation of tumor vasculature involves vasculogenic mimicry, which reflects the ability of aggressive tumor cells to express vascular-associated genes and form vasculogenic-like networks [11,12]. Finally, Holash et al. [13] have described the process of vessel cooption whereby malignant cells integrate existing host vessels to form a tumor mass that is well-vascularized even at an early stage. Thus, in order to develop antivascular therapeutic approaches, it is crucial to understand the relative contribution of each of these pathways to the development of tumor vasculature in specific tumor types.

This review focuses on selected antivascular strategies that are being developed for the treatment of gynecologic malignancies. The evaluation of these antivascular molecules poses new challenges in clinical trial design and assessment of response, which are also discussed in this paper.

VEGF and VEGF Receptors As Therapeutic Targets

Vascular endothelial growth factor, also known as vascular permeability factor, plays a critical role in vasculogenesis, in both physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis, and in lymphangiogenesis [14,15]. VEGF promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration, profoundly alters their pattern of gene expression, and protects them from apoptosis and senescence [16]. VEGF is a 35- to 45-kD dimeric polypeptide that is expressed in several isoforms and functions as a survival factor for endothelial cells via the phosphatidylinositol (PI)-3 kinase-Akt pathway in both in vitro and in vivo studies [15-17]. VEGF is widely overexpressed by various human cancer cells. We and others have shown that elevated tumor VEGF expression and serum VEGF levels in ovarian cancer patients are associated with poor clinical outcome [18]. Moreover, overexpression of VEGF in tumor cells enhances tumor growth and metastases in several animal models by stimulating neovascularization [19,20].

VEGF-A mediates its effects by interacting with two high-affinity transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2), which are mostly expressed on endothelial cells [16,21]. On binding to its receptors, VEGF initiates a cascade of signaling events that begins with autophosphorylation of both receptor tyrosine kinases, followed by activation of numerous downstream proteins, including PI3-K, GAP, MAPK, and others [22]. Although the specific biologic functions mediated by each receptor are not established with certainty, it is thought that VEGFR-2 is primarily responsible for mediating tumor microvascular permeability and subsequent endothelial cell proliferation and migration [23]. Studies from our and other groups suggest that VEGF receptors may also be expressed by cancer cells [12,24,25•]. Although the functional significance of the VEGF receptors on cancer cells is not fully known, it may be an additional therapeutic target.

Several novel approaches have been developed recently for targeting the ligand or VEGF-R for therapeutic applications. A recent study comparing multiple anti-angiogenesis approaches concluded that anti-VEGF strategies appear to be the most promising [26]. Bevacizumab is a humanized VEGF-A neutralizing monoclonal antibody and is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in combination with chemotherapy for patients with advanced colorectal cancer. This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival [27]. As a single agent, bevacizumab gave promising results in renal cancer [28] but failed to show benefit in a phase III clinical trial in metastatic breast cancer patients [29]. In preclinical studies in ovarian cancer, bevacizumab in combination with paclitaxel significantly decreased tumor burden and formation of ascites [30]. Remarkably, preliminary data from a phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab conducted by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer have shown objective responses, with some patients having a PFS of at least 6 months [31]. Thus, anti-angiogenic approaches show great promise for patients with ovarian cancer and will likely be studied in the next front-line trial in the GOG.

Recently, a novel approach to interfere with VEGF signaling using soluble decoy receptors, VEGF-trap, has been developed [32]. This construct incorporates domains of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 and binds VEGF with significantly higher affinity than previously reported VEGF antagonists [32]. VEGF-trap has a prolonged in vivo half-life and is able to abolish mature, preexisting vasculature followed by tumor regression in established xenografts. In ovarian carcinoma, systemic administration of the VEGF-trap prevented ascites accumulation and inhibited the growth of disseminated cancer [33]. Side effects of anti-VEGF therapies include hypertension, proteinuria, thrombosis, and transient grade 3 leukopenia. However, other than hypertension, no dose-related pattern of adverse effects was observed [34].

Investigators have demonstrated that inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR signaling, using either a function-blocking antibody or small molecule inhibitors such as PTK787 (blocks VEGFR phosphorylation), leads to inhibition of vascular permeability, and hence, to treatment of peritoneal ascites produced by ovarian cancer [35]. The advantage of using small molecule inhibitors is that they are orally active. The caveat however, is that treatment with these agents hits several different targets and thus may have increased side effects. These findings demonstrate the various pathways available for targeting VEGF signaling as viable anti-angiogenic strategies in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies.

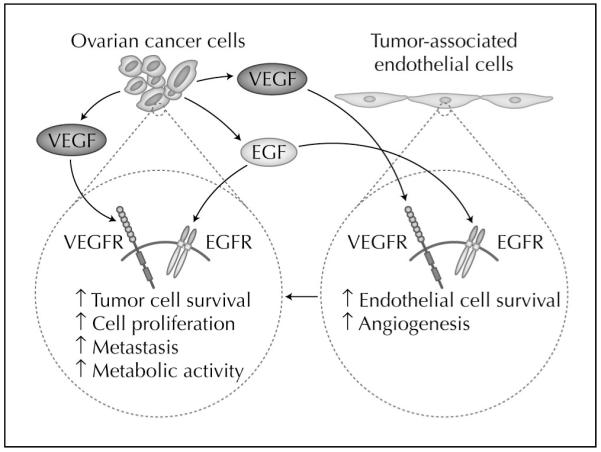

Another exciting antivascular approach is the dual targeting of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Agents such as AEE788 (Novartis Pharma, East Hanover, NJ) and ZD6474 (Astra-Zeneca, Alderley Park, Macclesfield, UK) are small molecule kinase–inhibitors that inhibit both VEGF-R and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Fig. 2) [36]. We recently demonstrated that ovarian cancer cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells express VEGFR, EGFR, and the phosphorylated forms of these receptors [25•]. Blockade of VEGFR and EGFR signaling pathways by oral administration of AEE788 combined with paclitaxel significantly reduced the growth of ovarian cancer xenografts in nude mice [25•]. Interestingly, treatment with AEE788 and paclitaxel produced apoptosis in both tumor-associated endothelial cells and in tumor cells regardless of their sensitivity to taxanes. These data as well as previous reports [37] suggest that the inhibition of RTKs in combination with cytotoxic agents has an antivascular effect by affecting tumor-associated endothelial cells. These agents are currently being evaluated in phase I clinical trials.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical model of dual targeting of tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells. Tumor cells and endothelial cells express some of the same genes that contribute to tumor neo-vascularization. For example, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular growth factor receptor (VEGFR) are expressed by tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells. Antivascular approaches that target both tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells may have the greatest therapeutic benefit.

The Role of Pericytes in Tumor Neovascularization

Although endothelial cells have attracted the most attention, other cell types likely play a significant role in tumor vascular development. Pericytes are stromal (mesenchymal) in origin and are required for normal microvascular stability and function [38]. These mural cells stabilize nascent blood vessels, provide hemostatic control, and protect endothelial-lined vessels against rupture or regression. Thus, by providing support to the newly formed blood vessels, pericytes play a critical role in the process of blood vessel maturation [39]. Unlike normal blood vessels, the amount of pericyte coverage on vessels in different tumors ranges from extensive to very sparse [40]. Previous studies have suggested that up to 90% reduction in pericyte coverage in mice is compatible with postnatal survival, whereas a loss of more than 95% is lethal [41]. This suggests that even small numbers of pericytes in tumor vessels are critical for blood vessel integrity and function. Pericytes produce VEGF, a known survival factor for endothelial cells [42,43]. Tumor vessels that lack pericyte coverage appear to be more dependent on VEGF for survival than vessels that are encased by pericytes [42], suggesting that pericytes provide a local survival advantage for endothelial cells. For example, in experimental models of gastric cancer, anti-angiogenic therapy effectively reduced the overall vessel density and stimulated endothelial cell apoptosis, but the fraction of pericyte-covered vessels increased following such therapy [44]. These results suggest that, in order to achieve the best therapeutic effect, it may be necessary to target more than one signaling pathway. Pericyte homeostasis is regulated largely by signaling through the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) ligand/receptor system [43]. PDGF is a major mitogen and chemoattractant for mesenchymal cells. PDGF exists as a disulfide-linked homodimer or heterodimer of A and B chains, resulting in three isoforms, each of which has different binding affinities for the two receptors, PDGFR-α and β [45]. Apte et al. [46] previously demonstrated that PDGF-AA and BB ligands are expressed in most ovarian cancer samples. PDGF-BB produced by tumor endothelium is required for adequate pericyte recruitment and proper integration of pericytes in the vascular wall [47]. Blockade of PDGFR-β using tyrosine kinase inhibitors has pointed to a functional role for PDGF in recruitment of pericytes in mouse insulinomas [48]. Interestingly, pericytes on developing immature blood vessels appear to be more dependent on PDGF compared with those found in mature vasculature [48]. However, PDGF targeting alone may not be effective in causing tumor regression. Jayson et al. [49] treated advanced colorectal and ovarian cancer patients with a humanized antibody to PDGFR-β. Inhibition of PDGF signaling causes an increase in the ratio of vascular volume to tumor volume. However, almost 30% of patients developed significant ascites after treatment with the drug [49]. Thus, it is apparent that the maintenance of tumor vasculature is dependent on several factors. Treatment strategies that target endothelial cells as well as supporting pericytes may produce improved therapeutic responses. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors that affect multiple RTKs, or combinations of inhibitors that block both VEGFR and PDGFR signaling pathways, may be used to achieve this goal. Thus, by reducing pericyte coverage in tumor blood vessels, it may be possible to sensitize endothelial cells to anti-angiogenic therapy [50].

Anti-angiogenic Scheduling of Chemotherapy

Proliferation of endothelial cells is an important component of tumor angiogenesis. In contrast to the endothelium of quiescent mature blood vessels, vascular endothelial cells proliferate rapidly in the tumor microenvironment [1,2,3••] and are highly sensitive to most chemotherapeutic agents in vitro. Currently, most chemotherapeutic agents are administered at their “maximum tolerated dose” (MTD) [51]. In an effort to balance toxicity with efficacy, conventional regimens are designed for episodic administration of cytotoxic agents at or near the MTD, followed by periods of rest, which allows recovery of normal tissues. Whereas chemotherapy at MTD likely also targets proliferating tumor endothelial cells, the obligatory rest periods allow endothelial cells to recover by using their intact p53-based DNA damage sensor and effecting G1 arrest. This allows repair of the damaged genome and diminishes the anti-angiogenic effects of this treatment [52••]. Hence, the main targets of dose-dense chemotherapy are the proliferating tumor cells, and these strategies have a limited effect on angiogenesis.

Metronomic chemotherapy is defined as the frequent administration of chemotherapeutic agents at doses substantially lower than the MTD without prolonged drug-free breaks [52••]. By increasing the frequency of administration of cytotoxic drugs at doses that are low enough to avoid myelosuppression and other side effects, it is possible to administer chemotherapy over prolonged periods without any intervening rest periods. This allows the slowly proliferating tumor endothelial cells to be continuously exposed to the damaging effects of chemotherapy and limits the opportunity for repair and recovery. Thus, the main targets of frequent or continuous metronomic chemotherapy are proliferating endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature [52••,53].

Metronomic dosing of chemotherapeutic agents has been effective in controlling the growth of tumors that were resistant to conventional scheduling. Low-dose cyclophosphamide administered every 6 days had better therapeutic effects than higher doses given every 21 days [53]. Similarly, in clinical trials, weekly taxane chemotherapy has been shown to result in a high rate of objective responses even in individuals with chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancers [54]. Certain cytotoxic agents, such as vinblastine, cyclophosphamide, and taxanes, have anti-angiogenic properties when administered at 10% to 20% of the MTD in combination with an anti-VEGFR-2 antibody [55]. It is known that high concentrations of VEGF in the tumor microenvironment can promote multidrug resistance in the tumor endothelial cells [55]. Thus, metronomic dosing of standard chemotherapeutic agents in combination with other antivascular agents may maximize the growth-limiting effects on the tumor vasculature and provide a means of overcoming resistance to therapy encountered with cytotoxic agents administered alone.

Among patients with ovarian carcinoma, metronomic chemotherapy may be useful for consolidation therapy after treatment with cytotoxic agents at MTD. Although minimal toxicity has been noted with metronomic chemotherapy in preclinical studies, possible disadvantages include the need for frequent dosing and the potential for cumulative toxicity with long-term use of cytotoxic agents.

Other Novel Antivascular Approaches in Clinical Development

Our growing understanding of the complex biology involved in tumor neovascularization has led to the development of several classes of drugs that target various aspects of the angiogenic process. Table 2 lists some of the antivascular drugs that are currently being evaluated in pre-clinical and clinical trials.

Table 2. Examples of novel classes of anti-angiogenic drugs.

| Class of drug | Examples | Mode of action |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors |

Marimastat, Bay 12-9566 | Inhibit MMPs, especially MMP-2 and MMP-9 |

| Anti-integrin antibodies | Vitaxin (humanized αvβ3 integrin antibody) |

Blocks αvβ3 integrin and causes endothelial cell apoptosis |

| Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors | EA5 (monoclonal antibody to EphA2) | Blocks EphA2 and blocks angiogenesis |

| Endogenous protein inhibitors | Angiostatin, endostatin | Unknown |

| Vascular targeting agents | Combretastatin, AVE 8062 | Tubulin binding agents, induce vascular-mediated tumor necrosis |

An alternative strategy to inhibition of tumor blood supply is the use of vascular targeting agents (VTAs). These are novel agents that cause a rapid and extensive shutdown of established tumor vasculature, leading to secondary tumor cell death characterized by an early and extensive tumor cell necrosis [56]. Preclinical studies have shown VTA-induced enhancement of the effects of conventional chemotherapy and radiation as well as anti-angiogenic agents [57]. Thus, VTAs may have the greatest therapeutic benefit as part of combined-modality regimens.

Although angiogenesis is a feature of most primary and metastatic tumors, it is now known that vasculogenic mimicry contributes to tumor vascularity in many malignancies. Recent data suggest that anti-angiogenic agents have differential effects on the growth and differentiation of endothelial and tumor cells. van der Schaft et al. [58•] demonstrated that anti-angiogenic inhibitors such as anginex, TNP-470, and endostatin were able to markedly inhibit growth and differentiation of endothelial cells in vitro but had no effect on melanoma cell vasculogenic mimicry. Similar cell-specific effects on growth and cord formation by endothelial cells and tumor cells have been reported by Rybak et al. [59]. These findings may contribute to the development of new antivascular therapeutic strategies that target both angiogenesis and tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry [58•,59].

Conclusions

Tumor neovascularization is a complex process that involves interaction between endothelial cells and host stromal cells within the tumor microenvironment. Several classes of antivascular agents have emerged as promising therapeutic options and are being evaluated for clinical efficacy. In addition, the anti-angiogenic or metronomic scheduling of current cytotoxic drugs alone or in conjunction with other anti-angiogenic drugs provides valuable options for patients with gynecologic malignancies. A better understanding of the biology of tumor neovascularization and characterization of vascular markers within various tumors will allow us to develop antivascular strategies that are effective and well tolerated.

The clinical development of antivascular agents poses new challenges for oncologists. Although traditional dosing of cytotoxic and other agents is based on MTD, such dosing schema may not be appropriate for biologic therapies. For targeted therapies, effect on the relevant target should be assessed to determine optimal biologic dosing. In human clinical trials, biologic response can be difficult to determine because it is not possible to perform repeated tissue biopsies. However, many surrogate markers are being developed, ranging from molecular imaging, measurement of circulating cytokines, circulating endothelial precursors [60], and nucleic acids [61], that may allow noninvasive monitoring of biologic response. These exciting developments hold promise for individualized therapeutic strategies in the future with lower overall toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported through the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center SPORE in ovarian cancer (1P50CA83639), Department of the Army (W81 XWH-04-0227), and the National Cancer Institute (CA 11079301 and CA 10929801).

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Bergers G, Banjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev, Cancer. 2003;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. This article provides a review of the process of angiogenesis.

- 4.Hobson B, Denekamp J. Endothelial proliferation in tumors and normal tissues: continuous labeling studies. Br J Cancer. 1984;49:405–413. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, et al. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:543–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.St. Croix B, Rago C, Velculescu V, et al. Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science. 2000;289:1197–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hida K, Hida Y, Amin DN, et al. Tumor-associated endothelial cells with cytogenetic abnormalities. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8249–8255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rafii S. Circulating endothelial precursors: mystery, reality and promise. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:17–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI8774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sood AK, Fletcher MS, Zahn CM, et al. The clinical significance of tumor cell-lined vasculature in ovarian carcinoma: implications for anti-vasculogenic therapy. Cancer Biol Therapy. 2002;1:661–664. doi: 10.4161/cbt.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sood AK, Seftor EA, Fletcher M, et al. Molecular determinants of ovarian cancer plasticity. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holash J, Wiegand SJ, Yancopoulos GD. New model of tumor angiogenesis: dynamic balance between vessel regression and growth mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Oncogene. 1999;18:5356–5362. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber HP, McMurtry A, Kowalski J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway: requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30336–30343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper BC, Ritchie JM, Broghammer CL, et al. Preoperative serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels: significance in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3193–3197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claffey KP, Brown LF, del Aguila LF, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by melanoma cells increases tumor growth, angiogenesis, and experimental metastases. Cancer Res. 1996;56:172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oku T, Tjuvajev JG, Migyagawa T, et al. Tumor growth modulation by sense and antisense vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression: effects on angiogenesis, vascular permeability, blood volume, blood flow, fluorodeoxglucose uptake, and proliferation of human melanoma intracerebral xenografts. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4185–4192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Detmar M, Dvorak AM. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular hyperpermeability, and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1029–1039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng H, Dvorak HF, Mukhopadhyay D. Vascular permeability factor (VPF)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 down-modulates VPF/VEGF receptor-2-mediated endothelial cell proliferation, but not migration, through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26969–26979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gille H, Kowalski J, Li B, et al. Analysis of biological effects and signaling properties of Flt-1 (VEGFR-1) and KDR (VEGFR-2): a reassessment using novel receptor-specific vascular endothelial growth factor mutants. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3222–3230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan F, Wey JS, McCarty MF, et al. Expression and function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 on human colorectal cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:2647–2653. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Thaker PH, Yazici S, Nilsson MB, et al. Antivascular therapy for orthotopic human ovarian carcinoma through blockade of the vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4923–4933. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2060. This article highlights the importance of dual targeting of VEGFR and EGFR for antivascular therapy.

- 26.Kuo CJ, Farnebo F, Yu EY, et al. Comparative evaluation of the antitumor activity of antiangiogenic proteins delivered by gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4605–4610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081615298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Case history: Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramaswamy B, Shapiro CL. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in combination with docetaxel in women with advanced breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2003;4:292–294. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2003.n.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu L, Hofmann J, Zaloudek C, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor immunoneutralization plus Paclitaxel markedly reduces tumor burden and ascites in athymic mouse model of ovarian cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1917–1924. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burger RA, Sill M, Monk BJ, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) or primary peritoneal cancer (PPC): a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study [abstract] Proc ASCO. 2005;23(16S):457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holash J, Davis S, Papadopoulos N, et al. VEGF-Trap: A VEGF blocker with potent anti-tumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11393–11398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byrne AT, Ross L, Holash J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-trap decreases tumor burden, inhibits ascites, and causes dramatic vascular remodeling in an ovarian cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5721–5728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupont J, et al. Phase 1 and pharmacokinetic study of VEGF Trap administered subcutaneously (sc) to patients with advanced solid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:14S. July 15 supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Yoneda J, Herrara C, et al. Inhibition of malignant ascites and growth of human ovarian carcinoma by oral administration of a potent inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:445–454. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Traxler P, Allegrini PR, Brandt R, et al. AEE787: a dual family epidermal growth factor receptor/ErbB2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4931–4941. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apte SM, Fan D, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Targeting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor in antivascular therapy for human ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:897–908. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nehls V, Drenckhahn D. The versatility of microvascular pericytes: from mesenchyme to smooth muscle? Histochemistry. 1993;99:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00268014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allt G, Lawrenson JG. Pericytes: cell biology and pathology. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000047855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wesseling P, Schlingemann RO, Rietveld FJ, et al. Early and extensive contribution of pericytes/vascular smooth muscle cells to microvascular proliferation in glioblastoma multiforme: an immuno-light and immuno-electron microscopic study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:304–310. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneursym formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukumura D, Xavier R, Sugiura T, et al. Tumor induction of VEGF promoter activity in stromal cells. Cell. 1998;94:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindblom P, Gerhardt H, Liebner S, et al. Endothelial PDGF-B retention is required for proper investment of pericytes in the microvessel wall. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1835–1840. doi: 10.1101/gad.266803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCarty MF, Wey J, Stoeltzing O, et al. ZD6474, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with additional activity against epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, inhibits orthotopic growth and angiogenesis of gastric cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1041–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly JD, Haldeman BA, Grant FJ, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates PDGF receptor subunit dimerization and intersubunit trans-phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8987–8992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apte SM, Bucana CD, Killion JJ, et al. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor and activated receptor in clinical specimens of epithelial ovarian cancer and ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrammsson A, Lindblom P, Betsholtz Endothelial and non-endothelial sources of PDGFB regulate pericyte recruitment ad influence vascular pattern formation in tumors. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI18549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, et al. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jayson GC, Parker GJ, Mullamitha S, et al. Blockade of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta by CDP860, a humanized, PEGylated di-Fab’, leads to fluid accumulation and is associated with increased tumor vascularized volume. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:973–981. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaheen RM, Tseng WW, Davis DW, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibition of multiple angiogenic growth factor receptors improves survival in mice bearing colon cancer liver metastases by inhibition of endothelial cell survival mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1464–1468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanahan D, Bergers G, Bergsland E. Less is more, regularly: metronomic dosing of cytotoxic agents can target tumor angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1045–1047. doi: 10.1172/JCI9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Kerbel RS, Kamen BA. The anti-angiogenic basis of metronomic chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:423–436. doi: 10.1038/nrc1369. This articles provides a review of the anti-angiogenic basis of metronomic chemotherapy.

- 53.Browder T, Butterfield CE, Kraling BM, et al. Anti-angiogenic scheduling of chemotherapy improves efficacy against experimental drug-resistant cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markman M, Hall J, Spitz D, et al. Phase II trial of weekly single-agent paclitaxel in platinum/paclitaxel-refractory ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2365–2369. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tran J, Master Z, Yu JL, et al. A role for survivin in chemo-resistance of endothelial cells mediated by VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4349–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072586399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denekamp J. Review article: Angiogenesis, neovascular proliferation and vascular pathophysiology as targets for cancer therapy. Br J Radiol. 1993;66:181–196. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-66-783-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorpe PE. Vascular targeting agents as cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:415–427. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0642-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.van der Schaft DWJ, Seftor REB, Seftor EA, et al. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors in vascular network formation by human endothelial and melanoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1473–1477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh267. This article provides evidence for therapeutic targeting of vasculogenic mimicry.

- 59.Rybak SM, Sanovich E, Hollingshead MG, et al. Vasocrine formation of tumor cell-lined vascular spaces: implications for rational design of antiangiogenic therapies. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2812–2819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaked Y, Bertolini F, Man S, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of the vasculogenic phenotype parallels angiogenesis: Implications for cellular surrogate marker analysis of angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamat AA, Sood AK, Simpson JL, et al. Elevated levels of plasma cell-free DNA in patients with ovarian cancer [abstract] Proceedings of the 96th annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;46:845. [Google Scholar]