Abstract

In kinetoplastid mitochondrial mRNA editing, post-transcriptional insertion or deletion of uridines is templated by guide RNAs (gRNAs). Pre-mRNAs are encoded by maxicircles, while gRNAs are encoded by both maxicircles and minicircles. We have investigated minicircle transcription and the processing of gRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. We find that minicircles are transcribed polycistronically and that transcripts are accurately processed by an ∼19S complex. This gRNA processing activity co-purifies with RNA editing complexes, and both remain associated in 19S complexes. Furthermore, we show that RNA editing complexes associate preferentially with a polycistronic gRNA over non-processed RNAs. We propose that the ∼19S complexes initially described as RNA editing complex I are gRNA processing complexes that cleave polycistronic gRNA transcripts into monocistrons.

Keywords: guide RNA/minicircle transcription/RNA editing/RNA processing/Trypanosoma brucei

Introduction

The mitochondrial DNA of Trypanosoma brucei is organized as a network of catenated maxicircles and minicircles, termed the kinetoplast (Englund et al., 1982; Stuart, 1983; Simpson, 1986). Maxicircles represent the typical mitochondrial genome, coding for rRNAs and several proteins involved in mitochondrial respiration. Numerous polycistronic transcripts have been detected, indicating that maxicircles are transcribed polycistronically (Feagin et al., 1985; Read et al., 1992; Koslowsky and Yahampath, 1997), and that transcripts require processing to generate mature rRNAs and mRNAs. These processing activities include cleavage to generate monocistrons, polyuridylation of rRNAs (Adler et al., 1991) and polyadenylation of mRNAs (Bhat et al., 1992; Read et al., 1994). Neither the sequence nor structural signals required for processing have been identified.

Some maxicircle genes encode cryptic transcripts that require post-transcriptional insertion or deletion of uridines to produce a functional mRNA, a process known as RNA editing (Benne et al., 1986; for recent reviews see Alfonzo et al., 1997; Stuart et al., 1997; Hajduk and Sabatini, 1998). In vitro evidence supports an enzymic cascade mechanism of RNA editing involving an editing site-specific endonuclease, TUTase, 3′ U-specific exonuclease and RNA ligase (Seiwert and Stuart, 1994; Cruz-Reyes and Sollner-Webb, 1996; Kable et al., 1996; Seiwert et al., 1996). In T.brucei, these activities sediment on glycerol gradients as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of ∼19S and ∼35–40S, complex I and complex II, respectively (Pollard et al., 1992; Corell et al., 1996; Kable et al., 1996; Seiwert et al., 1996; Adler and Hajduk, 1997; Rusche et al., 1997). Both complexes contain the editing site-specific endonuclease, TUTase, RNA ligase and guide RNAs (gRNAs). Complex II also contains pre-edited mRNA and likely represents the active editing complex (Pollard et al., 1992).

Information for editing maxicircle transcripts is provided by gRNAs. Mature gRNAs contain a 5′ anchor sequence of 10–15 nucleotides (nt), a guide sequence of ∼35 nt and a poly(U) tail of 5–15 nt that is post-transcriptionally added to the 3′ end. The gRNAs of T.brucei are encoded by minicircles, with the exception of gCOII, gMurfII-1 and gMurfII-2, which are found on maxicircles (Pollard et al., 1990; Sturm and Simpson, 1990; van der Spek et al., 1991). Minicircles are ∼1 kb circular DNA molecules, and there are ∼10 000 per kinetoplast network. Despite some conserved features, they are heterogeneous in sequence, representing the 250–300 sequence classes necessary to edit maxicircle transcripts (Steinert and van Assel, 1980; Jasmer and Stuart, 1986a,b). Each minicircle of T.brucei contains three or four potential gRNA transcription units, each flanked by 18 bp inverted repeats. The 18 bp inverted repeats have been proposed to function in minicircle gRNA expression, since transcription initiates 31–32 bp downstream of the 5′ inverted repeat at the conserved sequence 5′-RYAYA-3′ in the gRNA gene (Pollard et al., 1990). Since gRNAs have 5′ triphosphate ends, it has been thought that each gRNA gene contains its own transcriptional start and termination site.

Here, we report the detection of polycistronic transcripts from minicircles. We describe an assay using partially purified mitochondrial extract that accurately processes polycistronic gRNA substrates into monocistrons. This gRNA processing activity co-purifies with ∼19S RNA editing complexes, and we further demonstrate that RNA editing complexes associate preferentially with a polycistronic gRNA over non-processed RNAs. We believe that the 19S complexes initially described as RNA editing complex I represent gRNA processing complexes that associate with nascent gRNA transcripts to cleave them into monocistronic gRNAs. Complex I subsequently associates with additional components, such as the pre-edited mRNA and other proteins, to form mature ∼35–40S RNA editing complexes.

Results

Detection of polycistronic transcripts from minicircles

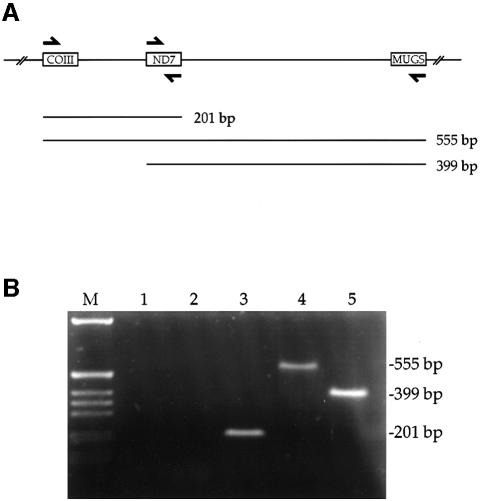

To determine whether minicircles are polycistronically transcribed, we isolated total mitochondrial RNA and analyzed the RNA by RT–PCR using primers that would detect polycistronic transcripts from a specific minicircle (Figure 1A). This minicircle encodes gRNAs for cytochrome oxidase subunit III (COIII), NADH dehydrogenase subunit 7 (ND7) and a minicircle unidentified gRNA sequence (MUGS). Using primers complementary to the 3′ end of ND7 and the 5′ end of the COIII gRNAs resulted in an RT–PCR product of 201 bp. This is the predicted size of a polycistronic transcript comprising the COIII and ND7 gRNAs and intergenic sequence (Figure 1B, lane 3). Similarly, RT–PCR with primers complementary to the 3′ end of MUGS and the 5′ end of either COIII or ND7 resulted in products of 555 and 399 bp, respectively. Again, this is consistent with the predicted size of polycistronic gRNA transcripts (Figure 1B, lanes 4 and 5). All products were dependent on the synthesis of cDNA (Figure 1B, lanes 1 and 2). The 555 bp product indicates that a single polycistronic transcript may contain all three gRNAs.

Fig. 1. Detection of polycistronic minicircle transcripts. (A) Diagram showing oligonucleotides (half arrows) used in RT–PCR and the expected products if minicircles are transcribed polycistronically. Boxes, gRNA genes for COIII, ND7 and MUGS. (B) Products were generated by RT–PCR from isolated mitochondrial RNA (lanes 3–5). Lane M, DNA ladder; lane 1, no RNA; lane 2, no reverse transcriptase.

We also examined whether transcription could span the minicircle. Using a primer that abuts the bent helical region with the 5′ COIII primer in RT–PCR, we were able to detect a polycistronic gRNA transcript of ∼670 bp. However, no products were detected using a primer complementary to a region flanking the origin of replication with the 5′ COIII primer (data not shown). Thus, a 3′ end boundary of transcription may reside within the bent helical and origin of replication regions of the minicircle.

Polycistronic gRNAs are processed by a 19S complex

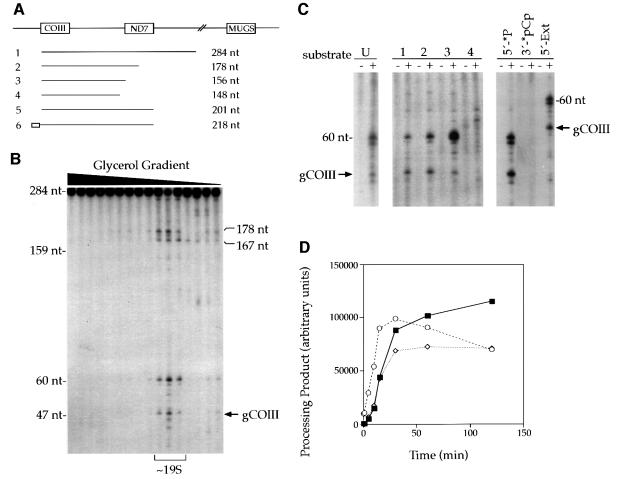

Since transcription of minicircles is polycistronic, mitochondria should contain an activity capable of processing polycistronic gRNA substrates. To assay for this activity, a dicistronic substrate containing the COIII and ND7 gRNAs was transcribed in vitro (Figure 2A, substrate 1). The substrate was radiolabeled at the 5′ end and used in processing reactions with mitochondrial extract that had been sedimented on a glycerol gradient. We detected gRNA processing activity at ∼19S that produced defined cleavages in the substrate (Figure 2B). One of the products is a gCOIII monocistron of ∼50 nt. A previous report indicated the activities of two mitochondrial endonucleases from T.brucei are affected by dithiothreitol (DTT) (Piller et al., 1997). However, no change in activity was observed in our assay over a range of 0–5 mM DTT (data not shown). We also tested processing at temperatures ranging from 4 to 42°C. We see a decrease in activity at temperatures >26°C and complete inactivation at >42°C (data not shown). The assays shown here were carried out with 5′ end radiolabeled substrates, but similar cleavages were seen with a uniformly radiolabeled substrate (Figure 2C, substrate U).

Fig. 2. In vitro processing of a polycistronic gRNA substrate. (A) Diagram of the minicircle and gRNA substrates assayed. (B) Polycistronic gRNA processing sediments as an ∼19S complex (see Materials and methods). Substrate 1 (A) was radiolabeled at the 5′ end and incubated with mitochondrial extract that had been sedimented on a glycerol gradient. Fractions containing the processing activity are bracketed. Arrow, gCOIII monocistron. (C) Characterization of the in vitro assay. Left panel, lane U, uniformly radiolabeled substrate 1. Middle panel, 3′ end deletions indicate that downstream sequence is required for 3′ end processing of gCOIII. Lanes 1–4, substrates 1–4 (A). Right panel, the in vitro assay shows no evidence for 5′ end processing. Substrate 5 was 5′ end (lane 5′-*P) or 3′ end (lane 3′-*pCp) radiolabeled to monitor production of either gCOIII or gND7, respectively. Substrate 6 (lane 5′-Ext) is a 5′ end 17 nt extension of substrate 5 to test for 5′ end processing of gCOIII. No 5′ end processing is detected, but 3′ end processing remains intact as demonstrated by the shift in products by 17 nt. (D) Time course. Reactions were incubated at 26°C and aliquots were removed at the indicated times. Products were quantitated using phosphoimagery. Closed squares, gCOIII; open diamonds, 60 nt product; open circles, products >160 nt. Similar results were found in duplicate experiments.

Truncations at the 3′ end of the substrate suggest that processing is dependent upon downstream sequence. A substrate with only half of gND7 results in 3′ end processing similar to that of the full-length substrate (Figure 2A and C, substrates 1 and 2). Deletion of all of gND7 results in significantly more 60 nt product (Figure 2A and C, substrate 3), and further removal of 8 nt completely abolishes 3′ end processing into the 60 nt and gCOIII products (Figure 2A and C, substrate 4). A new product of ∼110 nt is produced with this substrate (data not shown).

Next, we wanted to determine whether the in vitro assay resulted in 5′ end processing. A substrate that contains both the COIII and ND7 gRNAs (Figure 2A, substrate 5) was either 5′ or 3′ end radiolabeled to monitor processing of either gCOIII or gND7, respectively. The substrate radiolabeled at the 5′ end resulted in the expected 3′ end cleavage products of gCOIII and 60 nt (Figure 2C, lane 5′-*P), whereas the 3′ end radiolabeled substrate showed no evidence of 5′ end processing to produce the gND7 monocistron (Figure 2C, lane 3′-*pCp). We also tested a substrate that simply included an extension of 17 nt of minicircle sequence at the 5′ end of gCOIII (Figure 2C, lane 5′-Ext). Again, there is no evidence of 5′ end processing. However, 3′ end processing remains intact as demonstrated by the shift in sizes of the products by 17 nt.

Additional products of 60 nt and >160 nt were produced in these reactions. We investigated whether these might be processing intermediates in a time course and in processing assays using synthesized 60 nt and >160 nt RNAs as substrates. Quantitation of products over time suggests that the 60 nt product is not an intermediate as this product is generated coincidentally with that of the 47 nt gCOIII monocistron (Figure 2D). Additionally, when used as a substrate, the 60 nt product does not convert to the expected gCOIII monocistron (data not shown). Therefore, the 60 nt product may either represent an in vitro processing artifact or longer versions of this gRNA that may be found in vivo (Arts et al., 1993).

The products >160 nt, however, are generated earlier than the gCOIII monocistron, suggesting that they may be intermediates (Figure 2D). Since the >160 nt products are heterogeneous, we tested two substrates of 167 and 178 nt to determine whether they could be processed to gRNA-sized products (data not shown). The 167 nt substrate was not processed into a monocistron and may be an artifact of the assay. The 178 nt substrate, however, produced both the 60 nt product and the gCOIII, consistent with it being a processing intermediate. Thus, the data suggest that the dicistronic gRNA substrate is converted into the gCOIII monocistron by either single or dual 3′ end endonucleolytic cleavage(s).

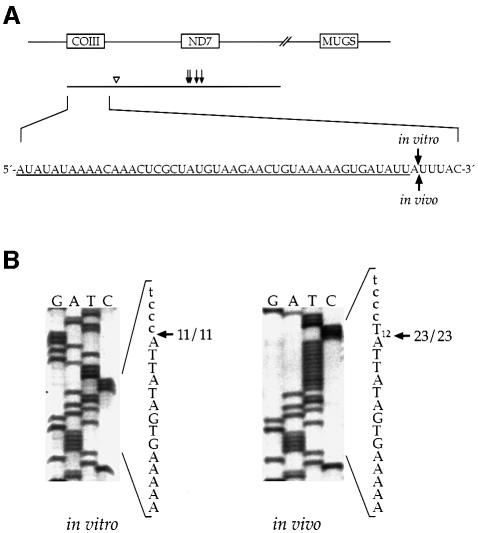

To map the precise 3′ ends generated by the in vitro cleavage of the COIII/ND7 substrate, we gel purified and sequenced the cleavage products (Figure 3A). The 3′ ends of the >160 nt products were found to be heterogeneous: five separate clones each had different 3′ ends. These products represented cleavages in the ND7 gRNA. Two 3′ ends, separated by 4 nt, were observed in the six clones obtained for the 60 nt products. The 3′ end of the processed gCOIII monocistron mapped to one site in 11 separate clones.

Fig. 3. The 3′ end of gCOIII produced in vitro is identical to the 3′ end found in vivo. (A) Diagram of the substrate assayed and products formed. The 3′ ends of the products >160 nt are heterogeneous and occur within gND7 (arrows), and the 3′ ends of the 60 nt product map to two sites near the 3′ end of gCOIII (open arrowhead). The 3′ end of gCOIII produced in vitro is identical to the 3′ end of gCOIII found in vivo (labeled arrows in sequence). (B) Sequences of the 3′ end of gCOIII produced in vitro and the 3′ end found in vivo. The 3′ end for both the in vitro generated and in vivo gCOIII is homogeneous in 11 and 23 clones, respectively. Poly(T) tract in the in vivo sequence represents the post-transcriptionally added poly(U) tail on mature gRNAs. Upper-case letters, gCOIII sequence; lower-case letters, vector sequence.

As another approach to determine whether gND7 is produced in the processing assay, we mapped the 3′ ends of gRNA-sized products from the uniformly radiolabeled substrate. These products map to the identical 3′ end of the gCOIII monocistron described above for the 5′ end radiolabeled substrate. We again find no evidence that downstream gND7 is processed to a monocistron.

To compare the gCOIII 3′ end produced in vitro and the 3′ end found in vivo, we cloned and sequenced endogenous gCOIII from total mitochondrial RNA. Only gRNAs with poly(U) tails were considered, since these likely represent functional gRNAs. The 3′ end of gCOIII found in vivo is homogeneous in 23 separate clones, and it is identical to that produced by the processing assay (Figure 3). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that in vivo cleavage occurs 1–3 nt after the 3′ A, since the DNA sequence around this 3′ end is 5′-ATTATTTAC-3′ and, thus, encoded uridines cannot be distinguished from the post-transcriptionally added poly(U) tail. gRNAs corresponding to the 60 nt in vitro product were not found in these studies, suggesting that the 60 nt product does not represent an abundant transcript in the steady state mitochondrial RNA pool.

Other polycistronic transcripts are accurately processed

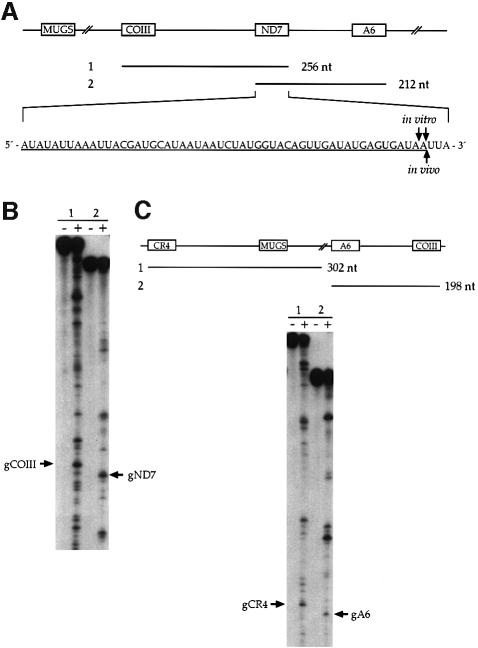

To determine whether other polycistronic transcripts are processed to mature size gRNAs, we tested transcripts generated from a minicircle containing MUGS, COIII, ND7 and ATPase subunit 6 (A6) gRNAs (Figure 4A). Two dicistronic substrates of COIII/ND7 and ND7/A6 were assayed. The in vitro activity processed the substrates into monocistronic COIII and ND7 gRNAs (Figure 4B). Similar to results seen in Figure 2, accurate 3′ end processing also required downstream sequence (data not shown). Processing of substrate 1 consistently produces an unusually high background. We have not attempted to optimize processing of this substrate, since all other substrates tested thus far are processed into well-defined cleavage products (see Figures 2 and 4). Additionally, two polycistronic gRNA substrates from another minicircle were also processed into well-defined cleavage products, including the monocistronic gRNAs (Figure 4C).

Fig. 4. Other polycistronic gRNAs are accurately processed. (A) Diagram of two substrates assayed. The precise 3′ end of gND7 generated in vitro and in vivo was determined (labeled arrows). (B) In vitro processing of substrates 1 and 2, incubated without (–) and with (+) ∼19S complexes purified by glycerol gradient sedimentation. Arrows, monocistronic gRNAs. (C) Two additional substrates are processed into monocistronic gRNAs, as indicated by arrows.

The 3′ ends of gND7 generated in vitro from the ND7/A6 substrate were compared with the 3′ end found in vivo (Figure 4A). Two 3′ cleavage sites out of four clones were mapped for the in vitro gND7. One of these sites is identical to the 3′ end of the gND7 found in vivo, while the other is 1 nt upstream. The 3′ end of the gND7 found in vivo was homogeneous in 20 clones. Again, we cannot exclude the possibility that in vivo cleavage occurs 1 or 2 nt after the 3′ A, since the DNA sequence flanking this 3′ end is 5′-GATAATTA-3′. The 3′ ends of gCR4 and gA6 produced in vitro were also determined. Each is precise, mapping to a single 3′ end.

gRNA processing co-purifies with 19S RNA editing complexes

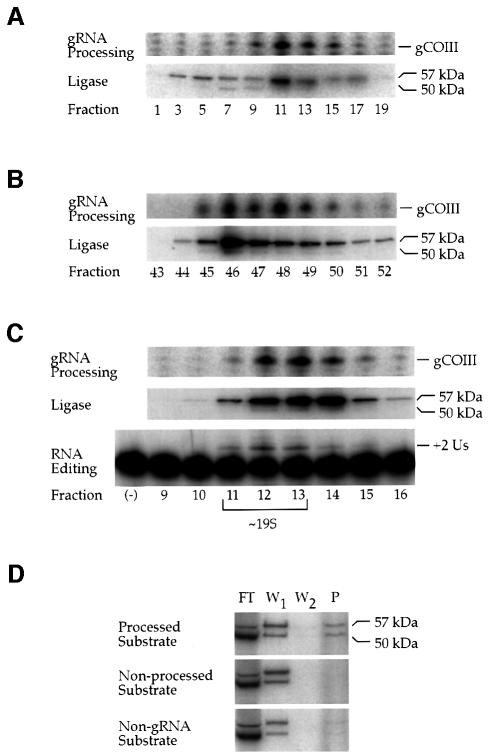

Polycistronic gRNA cleavage activity sediments at ∼19S on a glycerol gradient, corresponding to the same sedimentation value for RNA editing complex I (Pollard et al., 1992). The similarity in complex size suggested that there could be a physical association of the proteins involved in 3′ end cleavage of polycistronic gRNAs with those involved in RNA editing. To address this, we purified RNA editing complexes from mitochondrial extract by heparin and Q-Sepharose chromatography, followed by glycerol gradient sedimentation (McManus et al., 2000). Fractions containing RNA editing complexes were pooled based on both TUTase activity and the presence of the RNA editing complex-associated 50 and 57 kDa RNA ligases (Sabatini and Hajduk, 1995). All fractions were assayed for cleavage of a COIII/ND7 dicistronic gRNA substrate (Figure 2A, substrate 1). We find that polycistronic gRNA cleavage and RNA editing complexes co-purify through both heparin and Q-Sepharose chromatography (Figure 5A and B, respectively). After further purification of RNA editing complexes by glycerol gradient sedimentation, again, both gRNA processing and RNA editing complexes remain associated in ∼19S complexes (Figure 5C). Glycerol gradient fractions from the purification were assayed for in vitro insertional RNA editing. RNA editing sedimented with gRNA processing as ∼19S complexes (Figure 5C). Thus, our data support the view that polycistronic gRNA processing occurs within 19S RNA editing complexes.

Fig. 5. Polycistronic gRNA processing is associated with 19S RNA editing complexes. (A–C) Co-purification of polycistronic gRNA processing with RNA editing (see Materials and methods). Fractions from the purification were assayed for polycistronic gRNA processing and for the 57 and 50 kDa RNA ligases as markers of RNA editing complexes. gRNA processing and RNA editing complexes co-purify over heparin (A), Q-Sepharose (B) and glycerol gradient sedimentation (C). In vitro insertional RNA editing co-purifies with gRNA processing as an ∼19S complex (C), and is gRNA dependent [lane (–), pre-edited A6 mRNA incubated in a standard in vitro editing reaction without gRNA]. (D) RNA editing complexes are preferentially captured by a polycistronic gRNA that is processed versus a non-processed gRNA or non-gRNA substrate. Lane FT, flow through; W1, first wash; W2, second wash; P, pellet.

To examine further the association of gRNA processing with RNA editing, biotinylated RNAs were pre-incubated with crude mitochondrial extract. RNAs with their associated proteins were then captured with streptavidin paramagnetic particles. RNA editing complexes were detected by the presence of both the 50 and 57 kDa RNA ligases. To determine whether any association was due to the gRNA moiety over the polycistronic nature of the substrate, we assayed both a substrate that is accurately processed into a gCOIII monocistron (Figure 2A, substrate 1) and a substrate that is not accurately processed (Figure 2A, substrate 4). RNA editing complexes were captured by the polycistronic gRNA 4- to 6-fold more than a non-processed gRNA substrate (Figure 5D, lane P). Capture of RNA editing complexes was dependent on the presence of biotinylated RNAs. To exclude the possibility that the preferential association was due to the size difference of the substrates, we tested a 240 nt non-gRNA substrate. This non-gRNA substrate captured RNA editing complexes at levels similar to the non-processed gRNA substrate (Figure 5D). These results indicate that RNA editing complexes associate preferentially with a polycistronic gRNA.

Discussion

Polycistronic minicircle transcripts

Our results indicate that minicircles are transcribed polycistronically. We show that trypanosome mitochondria contain an activity that accurately cleaves polycistronic transcripts into monocistronic gRNAs, and that accurate 3′ end processing requires a downstream sequence. Previous studies have shown that transcription of gRNAs in T.brucei initiates at the conserved sequence 5′-RYAYA-3′ (Pollard et al., 1992). Similar to the related organism Trypanosoma equiperdum (Pollard and Hajduk, 1991), it is likely that each gRNA gene on the minicircles of T.brucei serves as an independent transcriptional initiation site. Thus, it was thought that transcription of gRNAs was discrete, i.e. each gRNA had its own transcriptional initiation and termination sites. Based on our data, we suggest that there is either a lack of termination signals or leaky termination signals, and that minicircle transcription is polycistronic. Our inability to detect a polycistronic transcript that spans the origin of replication may suggest that there is a termination signal in the region of bent helical DNA and origin of replication.

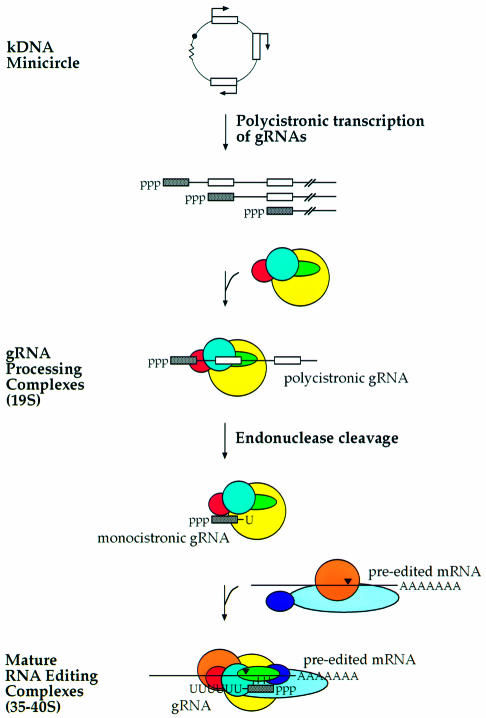

Polycistronic gRNAs could be processed into a single gRNA or multiple gRNAs. We demonstrate that mitochondrial extract accurately processes the 5′-most gRNA in the polycistronic transcript through 3′ end cleavage. However, we have no evidence for 5′ end processing, which would be required in processing downstream gRNAs to mature gRNAs. Thus, in our model of minicircle transcription, (i) each gRNA transcription unit initiates transcription at its 5′ end, (ii) a polycistronic gRNA is transcribed, (iii) an ∼19S complex accurately processes the 3′ end of the 5′-most gRNA to produce a monocistron and (iv) downstream sequence is degraded (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Model of the 19S and 35–40S RNA editing complexes revisited. Polycistronic minicircle transcripts assemble into 19S gRNA processing complexes, which process the 5′ most gRNAs into monocistrons (gray boxes). These complexes further associate with pre-edited mRNA and other proteins to form 35–40S RNA editing complexes that produce edited mRNAs. Red, endonuclease; yellow, TUTase; green, RNA ligase; closed arrowhead, editing site.

Association of polycistronic gRNA processing with RNA editing

We show that gRNA processing and RNA editing co-purify on heparin and Q-Sepharose chromatography, and that they remain associated in an ∼19S complex as determined by glycerol gradient sedimentation. We also demonstrate that RNA editing complexes associate preferentially with a polycistronic gRNA substrate over non-processed substrates. Thus, our results indicate a physical association of functionally related processing events, the generation of monocistronic gRNAs and RNA editing. We cannot exclude the possibility that the two activities exist in separate 19S complexes that coincidentally co-purify through three sequential purification steps. However, we believe this is unlikely. Similar purification schemes in our laboratory (Madison-Antenucci et al., 1998) and immunopurification of RNA editing complexes (Allen et al., 1998) have resulted in similar protein profiles of ∼13–15 polypeptides. Both of these purifications result in RNA editing complexes containing the requisite enzymic activities in addition to gRNAs (Allen et al., 1998; Madison-Antenucci et al., 1998) and mRNAs (Allen et al., 1998). Another laboratory has reported the purification of a minimal RNA editing complex containing eight major polypeptides but lacking associated gRNAs or mRNAs (Rusche et al., 1997). This may be the result of purification conditions that may strip away the requisite RNAs and associated polypeptides of native RNA editing complexes. Thus, we feel that the purification shown here represents highly purified native RNA editing complexes (McManus et al., 2000).

It is possible that gRNA processing and RNA editing have at least three components in common: an endonuclease, TUTase and gRNA. In gRNA processing, an endonuclease cleaves the polycistron into a monocistronic gRNA and TUTase adds the poly(U) tail. In RNA editing, an endonuclease cleaves the pre-edited mRNA and TUTase adds uridines to the 5′ cleavage fragment. The mature gRNA directs both the site of cleavage and the number of uridines added in the edited product. Thus, gRNA processing and RNA editing are functionally and physically linked. We propose a model whereby initial ∼19S complexes, containing shared components of gRNA processing and RNA editing, assemble with polycistronic gRNAs to process them into monocistronic gRNAs to be used in RNA editing (Figure 6). Subsequent association of pre-edited mRNAs and other proteins would form 35–40S RNA editing complexes that result in gRNAs with poly(U) tails and produce edited mRNAs. Further understanding of the functional and physical relationships awaits identification of the endonuclease(s) and other components of the gRNA processing and RNA editing complexes.

Materials and methods

Preparation of mitochondrial extract and mitochondrial RNA

Procyclic T.brucei TREU 667 cells were grown at 26°C in Cunningham medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cunningham, 1977). Mitochondria were isolated as previously described (Rohrer et al., 1987). Mitochondrial extract was prepared and sedimented on a 10–30% glycerol gradient as previously described (Pollard et al., 1992). For mitochondrial RNA isolation, mitochondrial extract was treated with proteinase K at 200 µg/ml for 30 min at 37°C, followed by extraction with phenol, phenol–chloroform and chloroform. After precipitation with ethanol, RNA was treated at 37°C for 15 min with 10 U of RNase-free DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim) in 200 µl of 50 mM Tris pH 7.9, 10 mM MgCl2 and 50 µg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA).

RT–PCR analysis

Reactions contained 0.3 µg of mitochondrial RNA, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.9, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml BSA, 1 mM dNTPs and 20 U RNasin (Promega) in a total volume of 20 µl. First strand cDNA was synthesized using 200 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc.) with 20 pmol of either 3′ND7 (5′-TATATCATA ATCATCA-3′) or 3′ MUGS (5′-TCTCTATCTTCTATGA-3′) primers. The entire reaction was added to PCR mix (80 µl) containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 pmol of 5′ primer, 30 pmol of 3′ primer and 1–2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer). PCR amplification [92°C for 30 s, 38°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min (30 cycles), with an initial step of 92°C for 1 min and a final step of 72°C for 5 min] was performed with primer combinations of 5′COIII (5′-ATATAT AAAACAAACTCG-3′)/3′ND7, 5′COIII/3′MUGS and 5′ND7 (5′-ATA TATAAAACATGGAAG-3′)/3′MUGS. Control reactions with no RNA and no reverse transcriptase were performed with both 3′ND7 and 3′MUGS primers present in the first strand cDNA synthesis step and all primer combinations in the PCR amplification. The same results were seen in control reactions using pair combinations of primers (data not shown). RT–PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels and detected by staining with ethidium bromide.

Processing assay

The minicircle clone (minicircle Taq5) used in this study has been described previously (Pollard et al., 1990). 5′T7-Taq5-COIII (5′-TAA TACGACTCACTATAGGGATATATAAAACAAACTCGCTATGT AAG-3′) with either 3′Taq5-ND7 (5′-TAGCACTATTTCTGC ATACAAACGACTCC-3′), 3′halfND7 (5′-TTAGCTTCCATGTTT TATATATC-3′), 3′noND7 (5′-CATATTAATATCTTATATTT ACC-3′), 3′148 (5′-TATCTTATATTTACCTAATTCTTATCTAT TATATC-3′) or 3′ND7 primers were used to generate PCR templates from which substrate RNAs for processing reactions were made with T7 RNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Inc.). The 5′ extension substrate was made with 5′Ext (5′-TAATACGACTCACTA TAGGGTTATAATTAGATATTGTA-3′) and 3′ND7. The other substrates were generated from minicircle clones Taq4 or Taq6 described here. 5′T7-Taq4-COIII (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATA TATTACCAAACAATAGACGAG-3′) with 3′Taq4-ND7 (5′-TTA TCACTCATATCAACTGTACCATAG-3′) and 5′T7-Taq4-ND7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATATATTAAATTACGATGC ATA-3′) with 3′Taq4-A6 (5′-TATTAAATCACTTTACTTATTC TCG-3′) were used for the Taq4 substrates, while 5′T7-Taq6-TU1 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATATATAAAATTATAAC GTC-3′) with 3′Taq6-TU2 (5′-GTCTTTATCTACTCTAATTAC-3′) and 5′T7-Taq6-TU3 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATATAACAA TAAAACATAATC-3′) with 3′Taq6-TU4 (5′-ATATCATCACTTTCT TATATTCTC-3′) were used for the Taq6 substrates. Substrates were purified from a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel in RNA elution buffer (0.5 M sodium acetate and 0.1% SDS). For 5′ end radiolabeled substrates, RNAs were treated with alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) followed by 5′ end radiolabeling using [γ-32P]ATP (DuPont New England Nuclear) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Substrates were 3′ end radiolabeled with T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs) using [5′-32P]pCp. Reaction conditions were as specified by the manufacturer. Substrates were gel purified again and resuspended in water.

Each processing reaction contained 1 mM pyrophosphate, 1 U/µl RNasin (Promega), 50 mM Tris pH 7.9, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 30 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 fmol of substrate (∼1000 c.p.m.) and 5 µl of the indicated glycerol gradient fraction in a total reaction volume of 20 µl. The reactions were incubated for 1 h at 26°C. Reactions were stopped with 0.1% SDS, 0.3 M sodium acetate and 10 µg of glycogen. Following extraction with phenol–chloroform and precipitation with ethanol, reactions were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel and visualized by autoradiography. Quantitation was carried out using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager (Model #STORM-860).

Mapping 3′ ends

The 3′ ends of in vitro processing products and in vivo gRNAs were sequenced by the method of Liu and Gorovsky (1993) essentially as previously described (Adler and Hajduk, 1997). To sequence the 3′ ends of in vitro processing products, a larger scale processing reaction was performed with 20 pmol of unlabeled substrate and 7 µl of glycerol gradient fraction alongside a standard radiolabeled reaction. The products were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gel in adjacent lanes. Using the radiolabeled lane as a marker, the appropriate regions of the gel were excised and extracted as described above. The products were resuspended in T4 RNA ligase buffer (New England Biolabs) containing 2 pmol of kinase-treated NE-4 (5′-CCCTTTAGTGAGGGTTAA TTGCGCGC-3′) oligonucleotide, and 10 U of T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs) in a total volume of 20 µl and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Following incubation, the samples were extracted and precipitated. RT–PCR was performed as described above with the 5′COIII and HT (5′-GCGCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAG-3′) oligonucleotides for gCOIII, with 5′ND7 and HT oligonucleotides for gND7, and with Taq4-ND7-L (5′-ATATATTAAATTACGATGCATAATAATCTATGGTAC AGTTG-3′) and HT oligonucleotides for gND7. The PCR products were gel purified and cloned into TA vector (Invitrogen). Sequencing was performed with [α-35S]dATP (DuPont New England Nuclear) and Sequenase (Amersham Life Science).

The in vivo gRNAs were sequenced similarly using 10 µg of mitochondrial RNA. The PCR was carried out with the HT oligonucleotide and either 5′COIII-L (5′-ATATATAAAACAAACTCG CTATGTAAGAACTGTAAAAAG-3′) for gCOIII or with Taq4-ND7-L for gND7.

Co-purification of gRNA processing and RNA editing activity

Purification of the editing complexes has been described (McManus et al., 2000). Protein adenylylation was carried out as described (Sabatini and Hajduk, 1995). The in vitro RNA editing assays were performed as described by Kable et al. (1996). All RNAs were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems 392 DNA/RNA synthesizer. The gA6[14] gRNA sequence has been described (Kable et al., 1996). The A6 mRNA substrate sequence is 5′-GGAAAGGUUAGGGGGAGGAGAGAAGA AAGGGAAAGUUGUGAUUGGAGUUAUAG-3′.

Biotinylated RNAs were transcribed in vitro according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, biotin-21-UTP (Clontech) was included in the in vitro reactions at ratios of 0:0 and 5:95, biotin-21-UTP to UTP. Incorporation of biotin-21-UTP was monitored according to manufacturer’s instructions. Substrate (50 fmol) was pre-incubated at 4°C for 15 min with 5 µl of crude mitochondrial extract in PB [1 U/ml RNasin (Promega), 50 mM Tris pH 7.9, 15 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT] for a 25 µl total volume. All subsequent steps were also carried out at 4°C. The reaction was added to 10 µl of Streptavidin MagneSphere Paramagnetic Particles (Promega), and biotinylated RNAs with their associated proteins were captured with a MagneSphere Technology Magnetic Separation Stand (Promega). The supernatant was removed (flowthrough, FT) and the particles were washed twice in 200 µl of PB (W1 and W2). Particles were resuspended in 10 µl of PB, and all fractions were adenylylated as described (Sabatini and Hajduk, 1995). Proteins in FT, W1 and W2 were acetone precipitated and all samples were analyzed by 10% SDS–PAGE.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Elliot Lefkowitz for helping with computer analysis of the Taq minicircle clones, and Karen Bertrand, Susan Madison-Antenucci and Robert Sabatini for useful discussion and criticism of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant AI21401 to S.L.H. and Medical Scientist Training Program grant 5T32GM08361 to J.G.

References

- Adler B.K. and Hajduk,S.L. (1997) Guide RNA requirement for editing-site-specific endonucleolytic cleavage of preedited mRNA by mitochondrial ribonucleoprotein particles in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5377–5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler B.K., Harris,M.E., Bertrand,K.I. and Hajduk,S.L. (1991) Modification of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondrial rRNA by posttranscriptional 3′polyuridine tail formation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 5878–5884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonzo J.D., Thiemann,O. and Simpson,L. (1997) The mechanism of U insertion/deletion RNA editing in kinetoplastid mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3751–3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen T.E., Heidmann,S., Reed,R., Myler,P., Goringer,H.U. and Stuart,K. (1998) Association of guide RNA binding protein gBP21 with active RNA editing complexes in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 6014–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts G.J., van der Spek,H., Speijer,D., van den Burg,J., van Steeg,H., Sloof,P. and Benne,R. (1993) Implications of novel guide RNA features for the mechanism of RNA editing in Crithidia fasciculata. EMBO J., 12, 1523–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benne R., van den Burg,J., Brakenhoff,J.P., Sloof,P., van Boom,J.H. and Tromp,M.C. (1986) Major transcript of the frameshifted coxII gene from trypanosome mitochondria contains four nucleotides that are not encoded in the DNA. Cell, 46, 819–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat G.J., Souza,A.E., Feagin,J.E. and Stuart,K. (1992) Transcript-specific developmental regulation of polyadenylation in Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 52, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corell R.A. et al. (1996) Complexes from Trypanosoma brucei that exhibit deletion editing and other editing-associated properties. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 1410–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Reyes J. and Sollner-Webb,B. (1996) Trypanosome U-deletional RNA editing involves guide RNA-directed endonuclease cleavage, terminal U exonuclease, and RNA ligase activities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8901–8906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham I. (1977) New culture medium for maintenance of tsetse tissues and growth of trypanosomatids. J. Protozool., 24, 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund P.T., Hajduk,S.L. and Marini,J.C. (1982) The molecular biology of trypanosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 51, 695–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J.E., Jasmer,D.P. and Stuart,K. (1985) Apocytochrome b and other mitochondrial DNA sequences are differentially expressed during the life cycle of Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 4577–4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduk S.L. and Sabatini,R.S. (1998) Mitochondrial mRNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. In Grosjean,H. and Benne,R. (eds), Modification and Editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Jasmer D.P. and Stuart,K. (1986a) Conservation of kinetoplastid minicircle characteristics without nucleotide sequence conservation. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 18, 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmer D.P. and Stuart,K. (1986b) Sequence organization in African trypanosome minicircles is defined by 18 base pair inverted repeats. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 18, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable M.L., Seiwert,S.D., Heidmann,S. and Stuart,K. (1996) RNA editing: a mechanism for gRNA-specified uridylate insertion into precursor mRNA. Science, 273, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koslowsky D.J. and Yahampath,G. (1997) Mitochondrial mRNA 3′ cleavage/polyadenylation and RNA editing in Trypanosoma brucei are independent events. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 90, 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. and Gorovsky,M.A. (1993) Mapping the 5′ and 3′ ends of Tetrahymena thermophila mRNAs using RNA ligase mediated amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE). Nucleic Acids Res., 21, 4954–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison-Antenucci S., Sabatini,R.S., Pollard,V.W. and Hajduk,S.L. (1998) Kinetoplastid RNA-editing-associated protein 1 (REAP-1): a novel editing complex protein with repetitive domains. EMBO J., 17, 6368–6376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus M.T., Adler,B.K., Pollard,V.W. and Hajduk,S.L. (2000) Trypanosoma brucei guide RNA poly(U) tail formation is stabilized by cognate mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piller K.J., Rusche,L.N., Cruz-Reyes,J. and Sollner-Webb,B. (1997) Resolution of the RNA editing gRNA-directed endonuclease from two other endonucleases of Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. RNA, 3, 279–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard V.W. and Hajduk,S.L. (1991) Trypanosoma equiperdum minicircles encode three distinct primary transcripts which exhibit guide RNA characteristics. Mol. Cell. Biol., 11, 1668–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard V.W., Rohrer,S.P., Michelotti,E.F., Hancock,K. and Hajduk,S.L. (1990) Organization of minicircle genes for guide RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. Cell, 63, 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard V.W., Harris,M.E. and Hajduk,S.L. (1992) Native mRNA editing complexes from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J., 11, 4429–4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read L.K., Myler,P.J. and Stuart,K. (1992) Extensive editing of both processed and preprocessed maxicircle CR6 transcripts in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 1123–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read L.K., Stankey,K.A., Fish,W.R., Muthiani,A.M. and Stuart,K. (1994) Developmental regulation of RNA editing and poly adenylation in four life cycle stages of Trypanosoma congolense. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol., 68, 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer S.P., Michelotti,E.F., Torri,A.F. and Hajduk,S.L. (1987) Transcription of kinetoplast DNA minicircles. Cell, 49, 625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusche L.N., Cruz-Reyes,J., Piller,K.J. and Sollner-Webb,B. (1997) Purification of a functional enzymatic editing complex from Trypanosoma brucei mitochondria. EMBO J., 16, 4069–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini R. and Hajduk,S.L. (1995) RNA ligase and its involvement in guide RNA/mRNA chimera formation. Evidence for a cleavage–ligation mechanism of Trypanosoma brucei mRNA editing. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 7233–7240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert S.D. and Stuart,K. (1994) RNA editing: transfer of genetic information from gRNA to precursor mRNA in vitro. Science, 266, 114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiwert S.D., Heidmann,S. and Stuart,K. (1996) Direct visualization of uridylate deletion in vitro suggests a mechanism for kinetoplastid RNA editing. Cell, 84, 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson L. (1986) Kinetoplast DNA in trypanosomid flagellates. Int. Rev. Cytol., 99, 119–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert M. and van Assel,S. (1980) Sequence heterogeneity in kinetoplast DNA: reassociation kinetics. Plasmid, 3, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart K. (1983) Mitochondrial DNA of an African trypanosome. J. Cell. Biochem., 23, 13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart K., Allen,T.E., Heidmann,S. and Seiwert,S.D. (1997) RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 61, 105–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm N.R. and Simpson,L. (1990) Kinetoplast DNA minicircles encode guide RNAs for editing of cytochrome oxidase subunit III mRNA. Cell, 61, 879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Spek H., Arts,G.J., Zwaal,R.R., van den Burg,J., Sloof,P. and Benne,R. (1991) Conserved genes encode guide RNAs in mitochondria of Crithidia fasciculata. EMBO J., 10, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]