Abstract

Methanolic extracts of 6 wild edible mushrooms isolated from the Western Ghats of Karnataka were used in this study. Among the isolates (Lycoperdon perlatum, Cantharellus cibarius, Clavaria vermiculris, Ramaria formosa, Marasmius oreades, Pleurotus pulmonarius), only 4 showed satisfactory results. Quantitative analysis of bioactive components revealed that total phenols are the major bioactive component found in extracts of isolates expressed as mg of GAE per gram of fruit body, which ranged from 3.20 ± 0.05 mg/mL to 6.25 ± 0.08 mg/mL. Average concentration of flavonoid ranged from 0.40 ± 0.052 mg/mL to 2.54 ± 0.08 mg/mL; followed by very small concentration of ascorbic acid (range, 0.06 ± 0.01 mg/mL to 0.16 ± 0.01 mg/mL) in all the isolates. All the isolates showed high phenol and flavonoid content, but ascorbic acid content was found in traces. Antioxidant efficiency by inhibitory concentration on 1,1-Diphenly-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) was found significant when compared to standard antioxidant like Buthylated hydroxyanisol (BHA). The concentration (IC50) ranged from 0.94 ± 0.27 mg/mL to 7.57 ± 0.21 mg/mL. Determination of antimicrobial activity profile of all the isolates tested against a panel of standard pathogenic bacteria and fungi indicated that the concentrations of bioactive components directly influence the antimicrobial capability of the isolates. Agar diffusion assay showed considerable activity against all bacteria. Minimum inhibitory concentration values of the extracts of 4 isolates showed that they are also active even in least concentrations. These results are discussed in relation to therapeutic value of the studied mushrooms.

Keywords: Agar diffusion assay, antioxidant, bioactive, DPPH mushrooms, in-vitro, Western Ghats

INTRODUCTION

Mushrooms have been shown to produce several biologically active compounds that are usually associated with cell wall, and these have been suggested to contribute to enhancement of immunity and tumor-retarding effects. Among the local communities, mushrooms may represent potential sources of antibacterial drugs, since in the early days, screening for antibiotics started with mushrooms and proved to be successful.[1]

People usually use fruit bodies and sclerotia of edible mushrooms as major food condiments that are served at their important family meals. Edible macro fungi are usually collected from the wild because farms growing them are very few.[2] Multiple-drug resistance in human pathogenic microorganisms has developed due to indiscriminate use of commercial antimicrobial drugs commonly used in the treatment of infectious diseases. This situation has forced scientists to search for new antimicrobial substances from various sources to be used as novel antimicrobial chemotherapeutic agents.[3] The scientific community, while searching for new therapeutic alternatives, has studied many kinds of mushrooms and has found various therapeutic activities such as anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, immuno-suppressor and antibiotic, among others. In recent decades, various extracts of mushrooms and plants have been of great interest as sources of natural products.[4] In recent years, multiple-drug resistance in human pathogenic microorganisms is rampant, due to indiscriminate use of antimicrobial drugs commonly used in the treatment of infectious diseases. In the continuous search for new antimicrobial structures, mushrooms are of interest to investigators. Sixty antimicrobial compounds have been isolated from mushrooms; however, only the compounds from microscopic fungi have been present in the market as antibiotics until now.[5]

Phenolic compounds have attracted much interest recently because in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that they have a variety of beneficial biological properties which may play an important role in the maintenance of human health. Their significance in the human diet and their antimicrobial activity have been recently established. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Laetiporus sulphureus were reported and correlated to the phenols and flavonoids contents.[6]

The aim of the present work was to carry out in vitro experiments to screen for bioactive compounds such as total phenols, flavonoids, ascorbic acid content, 1,1-Diphenly-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging assay; and moreover, their antimicrobial potential when derived from methanolic extract of wild edible mushrooms. Not much literature is available with regard to their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. The present study reveals the biopharmaceutical potential of mushrooms.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Chemicals

1,1-Diphenly-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), butylated hydroxyanisol (BHA), gallic acid, Folinciocalteu's phenol reagent (FCR), sodium carbonate, methanol, chloroform (Merck, Germany). Remaining chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Mushrooms

Among the isolated mushrooms, 6 edible species were selected from non-gilled fungal group of Aphyllophorales Viz: Lycoperdon perlatum (Pers.), Cantharellus cibarius (Fries), Clavaria vermiculris (Fries), Ramaria Formosa (Fr.) Quel, Marasmius oreades (Bolt. ex Fr), Pleurotus pulmonarius (Fr.) Quel Fr. were used in this study. Both young and old basidiocarps were collected from Dandeli, Sambrani and Karlakatta forests of Western Ghats of Karnataka. Identification was done by comparing their morphological, anatomical and physiological characteristics and monographs with descriptions given in the manual[7] and also through the electronic data on identification keys of mushrooms.[8] All the specimens were deposited at the herbarium of mycology laboratory, Department of Botany, Karnatak University, Dharwad. Karnataka.

Preparation of methanolic extracts

Preparation of methanolic extracts of mushrooms was done based on procedures described by Barros et al[9] with some modifications. A fine-dried mushroom powder sample (100 g) was extracted by stirring with 100 mL of methanol at 25°C at 150 rpm for 24 hours and filtered through Whatman no. 4 paper. The residue was then extracted with two additional 100-mL portions of methanol. The combined methanolic extracts were evaporated at 40°C to dryness. The organic solvent in the extracts was removed by a rotary evaporator. For the entire analysis, compounds of extract were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and filter-sterilization was done through a 0.22-μm membrane filter. Extracts were kept in the dark at 4°C for not more than 1 week prior to use.

Determination of bioactive components

Phenolic compounds in the mushroom methanolic extracts were estimated by a colorimetric assay, wherein 1 mL of sample was mixed with 1 mL of Folin and Ciocalteu's phenol reagent. After 3 minutes, 1 mL of saturated sodium carbonate solution was added to the mixture and adjusted to 10 mL with distilled water.[9] The reaction was kept in the dark for 90 minutes, after which the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically (Model - UV-1601 SHIMADZU) at 765 nm. Gallic acid was used to calculate the standard curve (0.01-0.4 mM). The mean values of results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAEs) per gram of extract.

Flavonoid concentrations were determined,[1] where in methanolic extract solution (1 mL) was diluted with 4.3 mL of 80% aqueous ethanol, and 0.1 mL of 10% aluminum nitrate and 0.1 mL of 1 M aqueous potassium acetate were added. After 40 minutes at room temperature, the solution was mixed well, and the intensity of the pink color was measured spectrophotometrically (Model - UV-1601 SHIMADZU) at 415 nm. Quercetin was used to calculate the standard curve of total flavonoid concentration absorbance = 0.002108 μg quercetin – 0.01089 (R2: 0.9999).

Ascorbic acid was determined,[9] where in methanolic extract (100 mg) was extracted with 10 mL of 1% metaphosphoric acid for 45 minutes at room temperature and filtered through Whatman no, 4 filter paper. The filtrate (1 mL) was mixed with 9 mL of 2, 6-dichloroindophenol, and the absorbance was measured within 30 minutes at 515 nm against a blank. Content of ascorbic acid was calculated on the basis of the calibration curve of authentic L-ascorbic acid (0.020-0.12 mg/mL). The results were expressed as milligrams of ascorbic acid per milliliter of extract. All the above estimations of bioactive compounds were carried out in triplicate and means were plotted.

Scavenging activity on DPPH for antioxidant assay

DPPH scavenging assay was determined[10] with slight modification. Mushroom extracts (0.3 mL) were mixed with methanolic solution containing DPPH radicals (6 × 10-5 mM, 2.7 mL). The mixture was shaken vigorously and left to stand for 60 minutes in the dark (until stable absorption values were obtained). The reduction of the DPPH radical was determined by measuring the bleaching of the purple-colored methanol solution of DPPH at 517 nm. The radical scavenging activity (RSA) was calculated as a percentage of DPPH discoloration using the following equation:

% RSA = [(ADPPH - AS)/ADPPH] × 100,

where AS is the absorbance of the solution when the sample extract has been added at a particular level, and ADPPH is the absorbance of the DPPH solution. The extract concentration providing 50% of radicals scavenging activity (IC50) was calculated from the graph of RSA percentage against extract concentration. BHA was used as standard. Extract concentration providing 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated from the plotted graph of inhibition percentage against extract concentration. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

Determination of antimicrobial efficacy

Microbial test organisms

Test organisms and culture media: The bacterial test organisms used were two gram-positive species Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633); gram-negative species Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) grown in Mueller Hinton agar at 37°C for 24 hours (Merck). Fungal species was unicellular Candida albicans (ATCC 60192) grown in potato dextrose agar (Hi Media) at ambient temperature for 72 hours.

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity of methanolic extract of mushrooms was determined by the agar well diffusion method,[11] with slight modification to suit the conditions of this experiment. Briefly, the methanol extracts were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL, and filter sterilized through 0.45-μm membrane filter. Small wells (6 mm in diameter) were made in the agar plates by sterile cork borer. One hundred microliters of the extract of each isolate of mushrooms was loaded into the different wells. Concentration of target microbial cells suspensions was adjusted to 104 cfu/mL. In order to determine the antimicrobial efficacy of the fractions, aliquot of test culture (100 μL) was evenly spread over the surface of the solidified agar. Bacteria were cultured on Mueller Hinton agar; and fungi on potato dextrose agar. Ampicillin (10 μg/mL) for bacteria, nystatin (100 U) for fungi were used as positive control and DMSO was used as negative control for test microorganisms. All the preloaded plates with respective extract and test organism were incubated at 37° C, for 24 hours for bacteria and at 27° C. 48 hours for fungi. After incubation period, zone of inhibition was measured in millimeters. All the tests were carried out in triplicate and their means recorded.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay

The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the compounds to inhibit the growth of microorganisms. The MIC values were studied for the microbial strains, being sensitive to the extracts in the agar well diffusion method. From the stock solutions of the extracts initially prepared a concentration of 10mg/mL of extract was added into the first wells. Then, dilutions were made so as to decrease the concentration of extract by 1 mg at each dilution. Positive and negative controls and incubation conditions were the same as in the zone of inhibition assay. Visible growth (turbidity) in the dilution tubes was the criterion to determine MIC values for the tested microorganisms at the given concentration of each extract. The extract in this study was tested in triplicate against each test organism.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate. Data obtained were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, and means were compared by Duncan's tests (SPSS 9 Student version). Differences were considered significant at P< 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In the present experiment, 6 species of wild edible mushroom isolated from the Western Ghat forests of Karnataka were evaluated for their content of total phenols, flavonoid and ascorbic acid. Obtained methanolic extracts were screened for their DPPH scavenging assay and antimicrobial efficacy. These assays were carried out using the DMSO solvent. In this study, only 4 species (L. perlatum, C. vermiculris, M. oreades and P. pulmonarius) showed significant and satisfactory results when compared to the other 2 isolates and the isolates in the research work found in recent literatures.

Bioactivecomponents

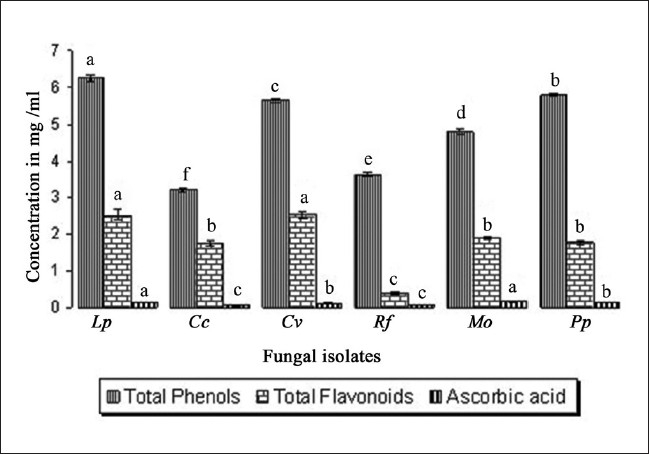

Figure 1 shows phenol, flavonoid and ascorbic acid concentrations of the isolates; total phenols are the major bioactive component found in extracts of isolates expressed as mg of GAE per gram of fruit body, which ranged from 3.20 ± 0.05 mg/mL to 6.25 ± 0.08 mg/mL. Average concentration of flavonoid ranged from 0.40 ± 0.052 mg/mL to 2.54 ± 0.08 mg/mL; followed by very small concentration of ascorbic acid (range, 0.06 ± 0.01 mg/mL to 0.16 ± 0.01 mg/mL) in all the isolates. The total phenolic compound amount was calculated to be quite high in M. conica ethanol extracts (41.93 ± 0.29 μg mg-1 pyrocatechol equivalent).[3] The total phenolic compound amount was calculated to be quite high for R. flava ethanol extracts (39.83 ± 0.32 μg mg-1 pyrocatechol equivalent). In contrast to this, the total flavonoid compound concentration was measured to be 8.27 ± 0.28 μg mg-1 quercetin equivalent.[12] Free radical scavenging (FRS) activity was compared with the standard phenolic, BHA, which gave an IC50 of >1.5 μg of equivalent phenol. T. heimii, T. mummiformis and B. edulis expressed very high activity; and Cantharellus cibarius with an IC50 of 0.23 mg/mL showed 10-fold lower activity compared to the collected sample Termitomyces heimii.[13] The total phenolic compound amount was calculated to be quite high for RD ethanol extract (47.01 ± 0.29 μg mg-1 pyrocatechol equivalent). According to Kim et al,[4] it is possible that the high inhibition value of RD extract is due to the high concentration of phenolic compounds. Total phenols were the major bioactive components found in the extracts, while ascorbic acid was found in small amounts (0.08-0.16 mg/g).[9] S. crispa, a medicinal mushroom, contained the largest total concentration of phenolic compounds (764 μg/g), while Agaricus bisporus was the edible species with the most phenolics (543 μg/g). Inonotus obliquus contained the largest total concentration of flavonoids (143 μg/g), while Phellinus linteus had no flavonoids.[14] The amount of total phenolic compounds of mycelium was the highest (P< 0.05) at 31.20 mg of GAE per g of mycelium, followed by oven-dried, freeze-dried and fresh fruit body. Total phenolic content of BHA was 417.84 ± 28.97 mg of GAE per g of BHA.[5] Bioactive components of all the six mushrooms were listed in Table 1 where total phenols ranged from 3.20 ± 0.05 mg/mL to 6.25 ± 0.08 mg/mL, total flavonoid ranged 0.40 ± 0.052mg/mL to 2.54 ± 0.08 mg/mL followed by ascorbic acid ranged 0.06 ± 0.01 mg/mL to0.16 ± 0.01 mg/mL. Higher contents of bioactive compounds were found in stage I (immature fruiting bodies) for L. deliciosus while for L. piperatus stage II (mature with immature spores) presented the highest content.[9]

Figure 1.

Bioactive components of methanolic extract of mushrooms Lp - Lycoperdon perlatum; Cc - Cantharellus cibarius; Cv - Clavaria vermiculris; Rf- Ramaria formosa; Mo - Marasmius oreades; Pp- Pleurotus pulmonarius; Vertical bars indicate standard error followed by alphabetic letters denotes significantly (P> 0.05) different

Table 1.

Bioactive compound contents of the wild edible mushrooms (Mean ± Standard Deviation; n=3)

Antioxidant assay

DPPH scavenging assay was measured at 517 nm. Positive DPPH test suggests that methanolic extracts of all the samples were scavengers of free radicals. The 50% of inhibition values (IC50) ranged from 0.94 ± 0.27 to 7.57 ± 0.21 mg/mL). The RSAs of BHA and isolates on DPPH radical are compared and shown in Figure 2. Among the studied concentrations, RSA was significant in L. perlatum (0.94 ± 0.27 mg/mL), followed by P. pulmonarius (1.62 ± 0.2 mg/mL). Other isolates showed satisfactory RSA in C. vermiculris (2.63 ± 0.14 mg/mL) and M. oreades (3.54 ± 0.18 mg/mL), and the remaining 2 isolates showed vestigial RSA when compared with commonly used synthetic antioxidant BHA (0.80 ± 0.00 mg/mL). According to Barros et al,[10] A. silvaticus was the most efficient species, showing higher value (5.37 ± 0.06 mg/mL), while A. arvensis presented lower antioxidant properties, with lower (15.85 ± 0.27 mg/mL) concentration, which is compatible to its lower phenols content. EC50 values of the extracts in DPPH radical scavenging of the fresh fruit body, oven-dried fruit body, freeze-dried fruit body and mycelium extracts were approximately 3.75, 5.81, 8.67 and 13.67 mg/mL, respectively, whereas that of BHA was 0.0126 mg/mL.[5] When the reaction time was kept at 1 minute, DPPH activity ranged between 15% (Pleurotus eryngii) and 70% (Ganoderma lucidum); while with a reaction time of 30 minutes, DPPH activity ranged between 5% (Pleurotus eryngii) and 78% (Agaricus bisporus). Overall, medicinal mushrooms had a higher DPPH activity than edible mushrooms.[14] Scavenging activities of D. indusiata were well pronounced at concentrations of 0.5 to 2 mg/mL. The free radical scavenging effect of WE was slightly higher than that of BHA at concentrations of 0.5 to 2 mg/mL.[11]

Figure 2.

Activity (IC50 in mg/mL) concentration of mushroom extracts Lp - Lycoperdon perlatum; Cc - Cantharellus cibarius; Cv - Clavaria vermiculris; Rf - Ramaria Formosa; M o - Marasmius oreades; Pp - Pleurotus pulmonarius; BHA - butylated hydroxytoluene (synthetic antioxidant). Error bars are standard error values of the mean denotes significantly (P> 0.05) different

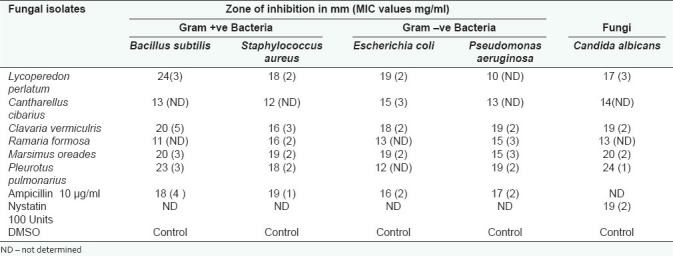

Antimicrobial assay

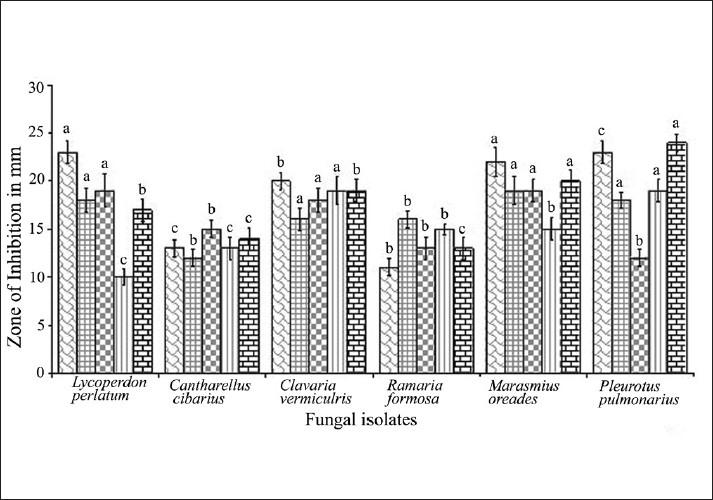

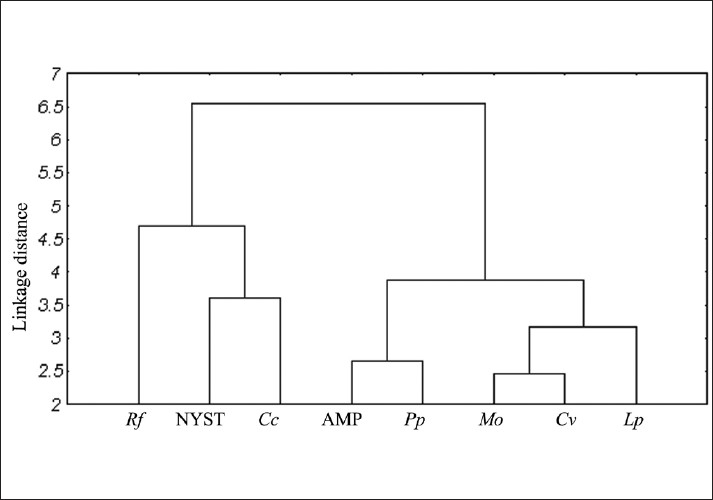

All the mushrooms used in this study were found to exhibit various degrees of antimicrobial effects against the tested microorganisms. The zone of inhibition exhibited more than 15 millimeter was considered as highly active for extracts. The best in-vitro antibacterial activity was by L. perlatum (24.0mm) followed by P. pulmonarius, M. oreades and C. vermiculris against E. coli. Antimicrobial concentrations exhibited by the mushroom extracts against the tested bacteria and fungi were listed in Table 2. Candida albicans was found to be very susceptible only to extract of P. pulmonarius and M. oreades when compared to positive controls. Antibacterial activity (22.0 mm) was exhibited by D. elegans against E. coli. This was followed in order by T. lobayensis, C. occidentalis and A. polytricha with values 20.0, 19.0 and 18.0 mm, respectively.[9,15] Pure extract of Polyporus giganteus produced the widest zone of inhibition (24.0 mm) against E. coli, followed by P. atroumbonata (18 mm) against the same bacteria. Pure extract of both Fomes lignosus and T. microcarpus produced inhibitory zones of 16.0 mm each against E. coli.[2] Figure 3 shows the comparative study of antimicrobial efficacy of methanolic extract and significant (P> 0.05) relationship among all the wild isolates. The MIC values indicate that among the selected microorganisms studied, extract of C. vermiculris and M. oreades inhibited the growth of gram-negative bacteria better than gram-positive bacteria and yeast. According to Ishikaw et al,[16] the antibacterial activities of aqueous extract of both edible Pleurotus sajarcaju and Agaricus were significant up to10% dilution against all the tested pathogens. B. cereus, B. subtilis, S. aureus and S. epidermidis presented high sensitivity to metabolic compounds of L. edodes, B. cereus and S. aureus are widely recognized as important food-borne pathogens, and the potential of its inhibition presented by L. edodes may receive more attention.[17] A high percentage of activity was also shown by extracts obtained from isolates belonging to the genus Ganoderma (62.5%), followed by extracts from species of Rigidoporus (27.2%). A low percentage of antimicrobial activity was shown by extracts of Phellinus species (7.8%).[18] Figure 4 summarizes the similarity of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations between the mushrooms extracts and Positive control in relation to their susceptibility to the tested microorganisms. These results reveal that M. oreades, P. pulmonarius, L. perlatum and C. vermiculris had comparatively similar concentrations of standard antimicrobials, which confirms the presence of bioactive components of edible mushrooms.

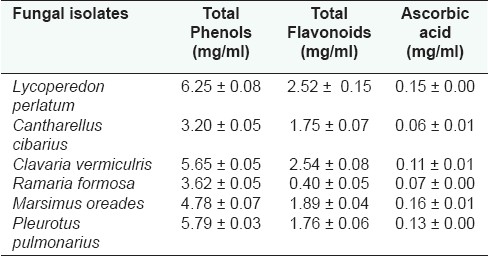

Table 2.

Antimicrobial efficacy of methanolic extract of wild edible mushrooms

Figure 3.

Antimicrobial efficacy of methanolic extract of wild edible mushrooms. Error bars are standard error values followed by letter denotes significantly (P> 0.05) different

Figure 4.

Similarity of minimum inhibitory concentration values of mushrooms when compared to control drugs in relation to their susceptibility to the test microorganisms

CONCLUSIONS

The present investigation can be concluded that the methanolic extract of 6 isolated wild edible mushrooms 4 species (Lycoperdon perlatum, Clavaria vermiculris, Marasmius oreades and Pleurotus pulmonarius) showed biopharmaceutical potentiality. Where antimicrobial efficacy is directly influenced by the phenolic contents and DPPH scavenging activity shows antioxidant nature of isolates is influenced by ascorbic acid content. However whether such extracts will act as effective therapeutic agents remain to be investigated, the identification of the bioactive compounds and study of mechanisms of actions are necessary prior to application.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to The Chairman Department of Botany, Karnatak University for providing laboratory facilities and Mo E. F. New Delhi for their financial assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The Chairman Department of Botany, Karnatak University for providing laboratory facilities and Mo. E. F New Delhi

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Opige M, Kateyo E, Kabasa JD, Olila D. Antibacterial activity of extracts of selected indigenous edible and medical mushrooms of eastern Uganda. Int J of trop med. 2006;1:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonathan G, Loveth K, Elijah O. Antagonistic Effect of Extracts of Some Nigerian Higher Fungi Against Selected Pathogenic Microorganisms American-Eurasian J. Agric and Environ. 2007;4:364–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turkoglu A, Kivrak I, Mercan N, Duru ME, Gezer K, Turkoglu H. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Morchella conica Pers. Afr J of Biot. 2006;5:1146–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz T, Mehmet ED, Nazime AM. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Russula delica Fr: An Edi Wild Mus Eur J of Ana Chem. 2007;2:64–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KH, Vikineswary S, Noorlidah A, Umah RK, Murali N. Effects of Cultivation Techniques and Processing on Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Hericium erinaceus (Bull. :Fr.) Pers. Ext Food Tech Biot. 2009;47:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barros L, Baptista P, Estevinho LM, Ferreira IC. Effect of fruiting body maturity stage on chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Lactarius sp. mushrooms. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:8766–71. doi: 10.1021/jf071435+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purkyastha RP, Aindrila C. Manual of Indian Edible Mushrooms. New Delhi: Today's and Tomorrow's Printers and Publication; 1978. p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo M. Contributors, Retreived from the MushroomExpert.Com. 2004. Available from: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/contributors .

- 9.Barros L, Calhelha RC, Vaz JA, Ferreira ICFR, Baptista P, Estevinho LM. Antimicrobial activity and bioactive compounds of Portuguese wild edible mushrooms methanolic extracts. Euro Food Res Technol. 2007;225:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barros L, Falcao S, Baptista P, Freire C, Vilas-Boas M, Ferreira ICFR. Antioxidant activity of Agaricus sp. mushrooms by chemical, biochemical and electrochemical assays. Food Chem. 2008;111:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyetayo VO, Dong CH, Yao YJ. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Aqueous Extract from Dictyophora indusiata. The Open Myco J. 2009;3:20–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gezer K, Duru ME, Kivrak I, Turkoglu A, Mercan N, Turkoglu H, et al. Free radical scavenging capacity and antimicrobial activity of wild edible mushroom from Turkey African. Journal of Biotechnology. 2006;5:1924–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puttaraju NG, Venkateshaiah SU, Dharmesh SM, Urs SM, Somasundaram R. Antioxidant activity of indigenous edible mushrooms. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9764–72. doi: 10.1021/jf0615707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim MY, Seguin P, Ahn JK, Kim JJ, Chun SC, Kim EH, et al. Phenolic compound concentration and antioxidant activities of edible and medicinal mushrooms from Korea. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:7265–70. doi: 10.1021/jf8008553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gbolagade S, Fasidi IO. Antimicrobial Activities of Some Selected Nigerian Mushrooms. Afr J of Biomed Res. 2005;8:83–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa NK, Kasuya MCM, Vanetti MCD. Antibacterial activity of Lentinula edodes grown in liquid medium Brazilian. J of Micro. 2001;32:206–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Getha K, Hatsu M, Wong HJ, Lee SS. Submerged cultivation of basidiomycete fungi associated with root diseases for production of valuable bioactive metabolites. J of trop forest sci. 2009;21:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tambekar DH, Sonar TP, Khodje MV, Khante BS. The novel antibacterial from two edible mushrooms Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus sajopr caju. Int J of Pharm. 2006;2:584–7. [Google Scholar]