Abstract

The present study reports protective activity of ethyl acetate fraction of methanol extract of stem bark of Ceiba pentandra against paracetamol-induced liver damage in rats. The ethyl acetate fraction (400 mg/kg) was administered orally to the rats with hepatotoxicity induced by paracetamol (3 gm/kg). Silymarin (100 mg/kg) was used as positive control. High performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) fingerprinting of ethyl acetate fraction revealed presence of its major chemical constituents. A significant (P < 0.05) reduction in serum enzymes GOT (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), GPT alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin content and histopathological screening in the rats treated gave indication that ethyl acetate fraction of methanolic extract of Ceiba pentandra possesses hepatoprotective potential against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

Keywords: Ceiba pentandra, hepatoprotective, hepatotoxicity, paracetamol

INTRODUCTION

Liver regulates many important metabolic functions, and any injury causes distortion of these metabolic functions. As per an estimate, about 20,000 deaths occur every year due to liver disorders. Hepatocellular carcinoma is 1 of the 10 most common tumors in the world, with over 250,000 new cases registered each year.[1] It has been reported that 160 phytoconstituents from 101 plants possess hepatoprotective activity.[2] Liver-protective herbal drugs contain a variety of chemical constituents like phenols, coumarins, lignans, essential oil, monoterpenes, carotinoids, glycosides, flavanoids, organic acids, lipids, alkaloids and xanthones derivatives. Extracts of about 25 different plants have been reported to cure liver disorders.[3] In spite of tremendous efforts made in the field of modern medicine, there are hardly any drugs yet designated that stimulate liver function, offer protection to the liver from damage or help regeneration of hepatic cell.[4] Many Indian ethno botanic traditions propose a rich repertory of medicinal plants used by the population for treatment of liver diseases. However, there were not enough scientific investigations on the hepatoprotective activities conferred to these plants.[5] In India, about 40 polyherbal commercial formulations are available and prescribed by physicians to treat hepatic disorders, but search for simple and precise herbal drug still poses an intriguing problem. Some of these plant drugs have also been reported to possess strong antioxidant activity.[6–8]

Ceiba pentandra (Bombacaceae) is an indigenous medicine, traditionally known by the name of Sweta Salmali in Ayurveda. The bark is acrid, bitter, thermogenic, diuretic, emetic, purgative and tonic; and useful in hepatopathy and vitiated condition of vata and kapha. The roots are diuretic, aphrodisiac, antipyretic. The leaves are used as an emollient; and the decoction of the flowers, as a laxative. The tree yields a dark, almost opaque, gum; it is astringent, tonic and laxative.[9–10] Alcohol extract of this plant has shown antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial activity. Isoflavonoid, sesquiterpene, naphthoquinone and water-soluble acidic polysaccharides were isolated from Ceiba pentandra.[11–17] The present study was undertaken to establish the traditional use of Ceiba pentandra as hepatoprotective against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The stem bark of Ceiba pentandra was collected in the month of September 2008 from the herbal garden of The M. S. University of Baroda, Gujarat, India, and identified at Botany Department, The M. S. University of Baroda. A voucher specimen (PG/NB/HDT-3-2009) was retained in our laboratory for further reference.

Drugs and chemicals

Silymarin was purchased from Micro Labs, Hosur, Tamil Nadu, India. The solvents and other chemicals were procured from SD Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India.

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing between 150 and 200 g were used for this study. The animals were procured from Zydus Laboratory, Ahmedabad, India. The animals were kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, at a room temperature of 22°C, with free access to food (Kisan Feed India Ltd., Mumbai, India) and water. The animals were acclimatized for a minimum period of 7 days. Experiments were conducted in the period between 0900 and 1400. The animals were used according to the guidelines of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, New Delhi. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee.

Preparation of extract

Defatted dried powdered stem bark was extracted with methanol in soxhlet apparatus (for 6 hours at 60°C), and volume was reduced to get dried powder with rotary vacuum evaporator. Total methanolic extract (10 gm) was dissolved in distilled water (100. ml) and partitioned with ethyl acetate (100 mL). Ethyl acetate was evaporated under vacuum to get the dried ethyl acetate fraction (5.33%). Silymarin was used as positive control at an oral dose of 100 mg/kg.[18] All the test substances were suspended in vehicle, i.e., 5% acacia mucilage. The extracts were tested for activity at doses of 400 mg/kg p.o.

Chemical analysis

Preliminary qualitative analysis of the ethyl acetate fraction showed the presence of tannin, C-glycoside, phenolic compounds, flavonoid, reducing sugar and triterpenes.

Chromatographic studies of extracts

HPTLC studies

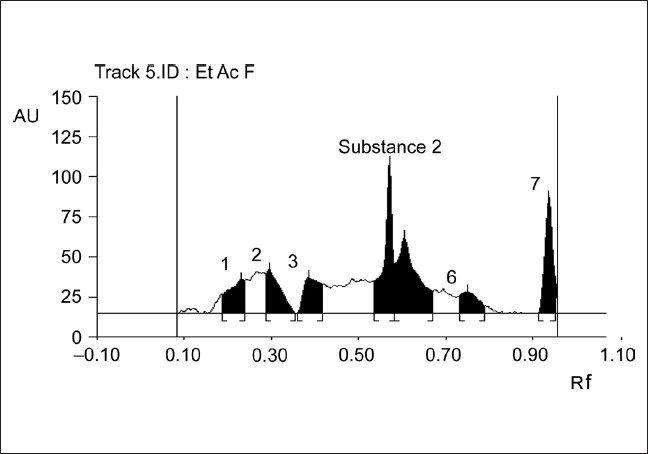

After optimization of mobile phase, a solvent system consisting of chloroform:ethyl acetate:methanol:formic acid (9:1:2:0.1) was selected to give the best resolution of seven spots. The detecting reagent was anisaldehyde in sulfuric acid followed by heating at 1108C for 5 minutes.

Pre-coated and pre-activated TLC plates (E. Merck No. 5548) of silica gel 60 F254 with the support of aluminum sheets having thickness of 0.1 mm were used.

Sample preparation

Two grams of ethyl acetate fraction of CP was weighed accurately and dissolved in 20 mL of methanol. Solution was then refluxed for 30 min on water bath at 60–70°C. The extract was cooled, filtered and finally the volume was made up to 20 mL with methanol.

Sample application

The sample was applied on TLC plate in the form of band using an automatic sample application device (LINOMAT V, CAMAG) with band width of 9 mm. The quantity of sample applied was 10 µL.

Development

The plate was developed by placing in pre-saturated chamber up to a height of 8 cm. It was developed in the optimized mobile phase, chloroform:ethyl acetate: methanol:formic acid (9:1:2:0.1). The plate was dried using an air dryer. Thereafter, it was derivatized with FeCl3 and scanned at 540 nm. The HPTLC densitogram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

HPTLC densitogram of ethyl acetate fraction of methanolic extract of CP

Toxicity studies

Acute toxicity study was performed for ethyl acetate fraction of methanolic extract according to the acute toxic classic method as per OECD guidelines.[19] Female albino rats were used for acute toxicity study. The animals were kept fasting overnight providing only water, after which the fractions were administered orally at a dose of 300 mg/kg and the animals were observed for 14 days. If mortality was observed in 2 out of 3 animals, then the dose administered was assigned as toxic dose. If the mortality was observed in 1 animal, then the same dose was repeated again to confirm the toxic dose. If mortality was not observed, the procedure was repeated for further higher dose, i.e., up to 2000 mg/kg.

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

Rats were divided into four groups of six each: Control, paracetamol-treated, silymarin-treated and test groups. The rats of control group received three doses of 5% acacia mucilage (1 ml/kg, p.o.) at 0 h, 12 h and 24 h. The rats of paracetamol group received three doses of vehicle at 12-hour intervals and a single dose of paracetamol (3 g/kg.) diluted in 0.5% carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) solution 30 minutes after the administration of first dose of vehicle. The animals in silymarin group received three doses of silymarin (100 mg/kg) at 0 h, 12 h and 24 h; paracetamol (3 g/ kg) was administered 30 minutes after the first dose of silymarin. The test groups were given the first dose of fraction in 0.5% carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) solution at 0 h, which was followed by a dose of paracetamol (3 g/kg.) after 30 minutes; while at 12 h and 24 h, the second and third dose of respective fraction (400 mg/ kg) was given.[20] After 36 hours of administration of paracetamol, blood was collected and serum was separated and used for determination of biochemical parameters.

Assessment of liver function

Blood was collected from all the groups by puncturing the retro-orbital plexus and was allowed to clot at room temperature, and serum was separated by centrifuging at 2500 rpm for 10 minutes. The serum was used for estimation of biochemical parameters to determine the functional state of the liver. Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) were estimated by a UV kinetic method based on the reference method of International Federation of Clinical Chemistry.[21] Alkaline phosphatase (ALKP) was estimated by the method described by Mac Comb and Bowers.[22] Total bilirubin (TBL) was estimated by Jendrassik and Grof method.[23] Total cholesterol (CHL) was determined by CHOD-PAP method of Richmond.[24] Total protein (TPTN) was estimated by Biuret method,[25] while albumin (ALB) was estimated by BCG.[26] All the estimations were carried out using standard kits on auto-analyzer of Merck make (300 TX, E. Merck-Micro Labs, Mumbai).

Histopathological studies

Livers of animals from the control and treated groups were used for this purpose. The animals were sacrificed and the abdomen was cut open to remove the liver. The liver was fixed in Bouin's solution (mixture of 75 mL of saturated picric acid, 25 mL of 40% formaldehyde and 5 mL of glacial acetic acid) for 12 hours and then embedded in paraffin using conventional methods.[27] Thereafter, it was cut into 5-µm thick sections and stained using hematoxylin-eosin dye and finally mounted in di-phenyl xylene. The sections were then observed under microscope for histopathological changes in liver architecture, and their photomicrographs were taken.

Statistical analysis

The mean values ± SEM were calculated for each parameter. For determining the significant inter-group differences, each parameter was analyzed separately, and one-way analysis of variance[28] was carried out. Individual comparisons of the group mean values were done using Dunnet's test.[29] P value less than 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

RESULTS

Acute toxicity studies

The ethyl acetate fraction of methanolic extract did not cause any mortality up to 2000 mg/kg and was considered as safe.

Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity

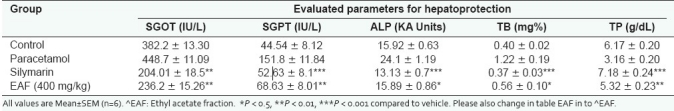

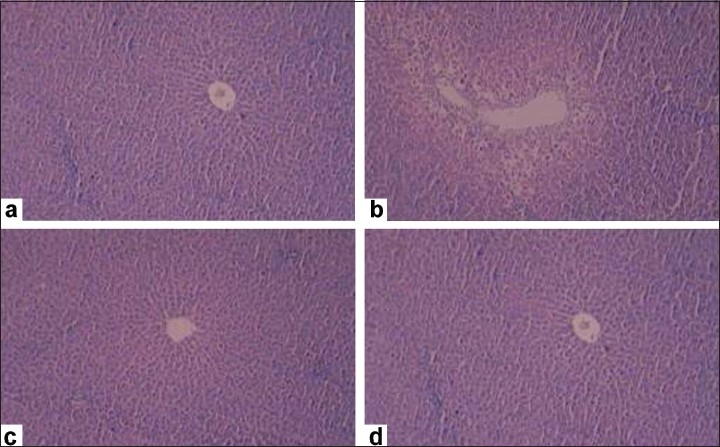

The results with regard to paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity are represented in Table 1. Paracetamol intoxication in normal rats elevated the levels of SGOT, SGPT, ALKP and TBL; whereas significant decrease in the levels of TPTN was observed, indicating acute hepatocellular damage and biliary obstruction. The rats that had received 400 mg/kg of EAFME (ethyl acetate fraction of methanolic extract) showed a significant decrease in all the elevated SGOT, SGPT, ALKP and TBL levels and significant increase in the reduced TPTN levels as compared to vehicle-treated group. Histopathological examination of liver sections of control group showed normal cellular architecture with distinct hepatic cells, sinusoidal spaces and central vein [Figure 2a]. Disarrangement of normal hepatic cells with necrosis and vacuolization were observed in paracetamol-intoxicated liver [Figure 2b]. Rat treated with 400 mg/kg ethyl acetate fraction and Silymarin followed by paracetamol intoxication [Figure 2c and d), significantly reduced the increase in the Liver weight and liver volume, seen after CCl4 intoxication.

Table 1.

Effect of EAF of stem bark of Ceiba pentandra on serum ALT, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin and total protein in paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs of histopathological changes showing effect of the test material on the rats intoxicated with carbon tetrachloride. a: Control; b: Carbon tetrachloride, 1.25 ml/kg i.p; c: Silymarin, 100 mg/kg p.o.; d: EAFME, 400 mg/kg p.o.

DISCUSSION

The paradigms used in the present study have been subjected to thorough critical appraisal and validated as animal models of hepatoprotective activity of CP in rats against paracetamol as hepatotoxin to prove its claims in folklore practice against liver disorders. Paracetamol hepatotoxicity is caused by the reaction metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzo quinoneimine (NAPQI), which causes oxidative stress and glutathione depletion. It is a well-known antipyretic and analgesic agent that produces hepatic necrosis at higher doses.[30] Paracetamol toxicity is due to the formation of toxic metabolites when a part of it is metabolized by cytochrome P-450. Introduction of cytochrome[31] or depletion of hepatic glutathione is a prerequisite for paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity.[32,33] Normally, AST and ALP are present in high concentrations in liver. Due to hepatocyte necrosis or abnormal membrane permeability, these enzymes are released from the cells and their levels in the blood increase. ALT is a sensitive indicator of acute liver damage, and elevation of this enzyme in non-hepatic diseases is unusual. ALT is more selectively a liver parenchymal enzyme than AST.[34] Assessment of liver function can be made by estimating the activities of serum ALT, AST, ALP and bilirubin, which are enzymes originally present in higher concentrations in cytoplasm. When there is hepatopathy, these enzymes leak into the bloodstream in conformity with the extent of liver damage.[35] The elevated levels of all these marker enzymes observed in group II, paracetamol-treated rats, in this present study corresponded to the extensive liver damage induced by toxin. The reduced concentrations of ALT, AST and ALP as a result of plant extract administration observed during the present study might probably be due in part to the presence of flavanoids. Bilirubin is one of the most useful clinical clues to the severity of necrosis, and its accumulation is a measure of binding, conjugation and excretory capacity of hepatocyte. Decrease in serum bilirubin after treatment with the extract in liver damage induced by paracetamol indicated the effectiveness of the extract in normalized functional status of the liver. Herbal drugs contain a variety of chemical constituents like phenols, coumarins, lignans, essential oil, monoterpenes, carotinoids, glycosides, flavanoids, organic acids, lipids, alkaloids and xanthones, which seem to be important for protection of liver.[36] In the present study, the ethyl acetate fraction of stem bark of Ceiba pentandra was found to contain tannin, C-glycoside, phenolic compounds, flavonoid, reducing sugar and triterpenes, thus confirming the ability of ethyl acetate fraction of stem bark of Ceiba pentandra to maintain normal functional status of the liver, which makes an addition in the list of safer herbal remedies for liver and its related disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Zydus Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, India, for generously providing the animals for the study. One of the authors, Nirmal Kumar Bairwa, is thankful to AICTE, New Delhi, for providing QIP fellowship.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolf PL. Biochemical diagnosis of liver diseases. Ind J Clin Biochem. 1999;14:59–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02869152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handa SS, Sharma A, Chakraborti KK. Natural products and plants as liver protecting drugs. Fitoterapia. 1986;57:307–51. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma SK, Ali M, Gupta J. Recent Progress in Medicinal Plants (Phytochemistry and Pharmacology) II. Houston, Texas (USA): Research Periodicals and Book Publishing House; 2002. Evaluation of Indian Herbal Hepatoprotective Drugs, Vol II, Research Periodicals and Book Publishing House, Houston, Texas (USA), ISBN No; pp. 253–70. ISBN No. 0-9656038-7-3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee TK. Herbal options. 3rd ed. Calcutta: Books and Allied (P) Ltd; 2000. Medicinal plants with hepatoprotective properties; pp. 135–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay RR. Possible mechanism of hepatoprotective activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract: Part II. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89:217–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achuthan CR, Babu BH, Padikkala J. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of rosa damascena. Pharma Biol. 2003;41:357–61. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aniya Y, Miyagi C, Nakandakari A, Kamiya S, Imaizumi N, Ichiba T. Free radical scavenging action of the medicinal herb Limonium wrightii from the Okinawa islands. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:239–44. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta K, Chitme H, Dass SK, Misra N. Antioxidant activity of Chamomile recutita capitula methanolic extracts against CCl4-induced liver injury in rats. J Pharma Toxicol. 2006;1:101–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants. second edition. III. 49-Leader Road, Allahabad: Lalit Mohan Basu; 1993. pp. 358–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phondke GP. The wealth of India, Raw material. Ca-Ci. 1992;III:408–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desire P, Djomeni D, Acha E. Hypoglycaemic and antidiabetic effect of root extracts of Ceiba pentandra in normal and diabetic rats. Afr J Trad CAM. 2006;3:129–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noreen Y, el-Seedi H, Perera P, Bohlin L. Two new isoflavones from Ceiba pentandra and their effect on cyclooxygenase-catalyzed-prostaglandin biosynthesis. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:8–12. doi: 10.1021/np970198+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngounou FN, Meli AL, Lontsi D, Sondengam BL, Atta-Ur-Rahman, Choudhary MI, et al. New isoflavones from Ceiba pentandra. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:107–10. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda H, Kaneda N, Kawanishi K, Alves SM, Moriyasu M. A New isoflavone glycoside from Ceiba Pentandra. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2002;50:403–4. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao KV, Sreeramulu K, Gunasekar D, Ramesh D. Two new sesquiterpene lactones from Ceiba pentandra. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:2041–5. doi: 10.1021/np50102a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kishore PH, Reddy MV, Gunasekar D, Caux C, Bodo B. A new naphthoquinone from Ceiba Pentandra. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2003;5:227–9. doi: 10.1080/1028602031000105812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shantha T, Raju D, Gowda C, Anjaneyalu YV. Structure of water-soluble acidic polysaccharides isolated from the bark of Ceiba Pentandra. Carbohydrate Res. 1989;191:321–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao KS, Mishra SH. Antihepatotoxic activity of monomethyl fumarate isolated from Fumaria indica. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;60:207–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.“Guidance document on acute oral toxicity testing” Series on testing and assessment No. 24, 1996 Organisation for economic co-operation and development, OECD Environment, health and safety publications, Paris. Available from: www.oecd.org/ehs .

- 20.Rao KS, Mishra SH. Screening of antiinflammatory and hepatoprotective activities of alantolactone isolated from the roots of Inula racemosa. Indian Drugs. 1997;34:571–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz MK, de Cediel N, Curnow DH, Fraser CG, Porter CJ, Worth HG, et al. International federation of clinical chemistry, education committee and international union of pure and applied chemistry, division of clinical chemistry: Definition of the terms certification, licensure and accreditation in clinical chemistry. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1985;23:899–01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McComb RB, Bowers GN., Jr Study of optimum buffer conditions for measuring alkaline phosphatase activity in human serum. Clin Chem. 1972;18:97–04. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jendrassik L, Grof P. Quantitative determination of total and direct bilirubin in serum and plasma. Biochem Z. 1938;297:81–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richmond W. Preparation and properties of a cholesterol oxidase from Nocardia species and its application to the enzymatic assay of total cholesterol in serum. Clin Chem. 1973;19:1350–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters T., Jr Proposals for standardization of total protein assays. Clin Chem. 1968;14:1147–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster D. A study of the interaction of bromocresol green with isolated serum globulin fractions. Clin Chim Acta. 1974;53:109–15. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(74)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galighor AE, Kozloff EN. Essentials of practical micro technique. 2nd ed. New York: Lea and Febiger; 1976. p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gennaro AR. The Science and Practice of Pharmacy. 19th ed. I. Easton PA: Mack publishing company; 1995. p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunnet CW. New tables for multiple comparisons with a control. Biometrics. 1964;20:482–91. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyd EM, Bereczky GM. Liver necrosis from paracetamol. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1966;26:606–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1966.tb01841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahlin DC, Miwa GT, Lu AY, Nelson SD. N-acetyl- p-benzoquinone imine: A cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:1327–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glulathione reductase and glutathione-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta AK, Chitme H, Dass SK, Misra N. Hepatoprotective activity of Rauwolfia serpentina rhizome in paracetamol intoxicated rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;1:82–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah M, Patel P, Phadke M, Menon S, Francis M, Sane RT. Evaluation of the effect of aqueous extract from powders of root, stem, leaves and whole plant of Phyllanthus debilis against CCL4 induced rat liver dysfunction. Indian Drugs. 2002;39:333–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nkosi CZ, Opoku AR, Terblanche SE. Effect of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo) protein isolate on the activity levels of certain plasma enzymes in CCl4-induced liver injury in low protein fed rats. Phytother Res. 2005;19:341–5. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta AK, Misra N. Hepatoprotective Activity of Aqueous Ethanolic Extract of Chamomile capitula in Paracetamol Intoxicated Albino Rats. Am J Pharm Toxicol. 2006;1:17–20. [Google Scholar]