Abstract

Objective

To assess whether postmenopausal women with breast cancer have a rapid decline in bone mineral density (BMD) after completion of tamoxifen therapy, similar to that seen after estrogen withdrawal.

Methods

We initiated a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of alendronate (70 mg weekly) in an effort to prevent bone loss associated with discontinuation of tamoxifen therapy. Postmenopausal women with breast cancer were randomly assigned to receive alendronate or placebo for 1 year within 3 months after withdrawal of tamoxifen therapy. Patients treated with aromatase inhibitors were excluded from the study. BMD at the spine, hip, and forearm was measured at baseline and at 12 months. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used for assessment.

Results

Patient accrual was considerably limited by the substantial increase in use of aromatase inhibitors during the enrollment period. The study patients (N = 11) had similar baseline BMD T-scores in the alendronate (n = 6) and placebo (n = 5) subgroups. After 1 year, tamoxifen withdrawal was associated with a significant decline in BMD at the femoral neck, which appeared to be prevented by weekly administration of alendronate (−5.2% versus 0.1%; P = .02). Levels of urinary N-telopeptide, a marker of bone turnover, increased by 48% in study subjects in the placebo group (P < .01), whereas weekly alendronate treatment was associated with a 52% decline (P < .01) in this bone resorption marker.

Conclusion

Differences in BMD and bone turnover were evident despite the small sample size. These data suggest that postmenopausal women with breast cancer completing tamoxifen therapy warrant an evaluation of their skeletal health and that bisphosphonate therapy may be useful in preventing bone loss associated with discontinuation of tamoxifen.

INTRODUCTION

Women with breast cancer are at increased risk for osteoporosis. The incidence of vertebral fractures is increased in this group, even in the absence of bone metastatic lesions (1). The breast cancer itself seems to produce various cytokines and other factors that increase bone resorption (2). In addition, chemotherapy used to treat breast cancer can predispose women to osteoporosis both by increasing bone resorption and by causing premature menopause (3,4).

The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen has a deleterious effect on bone density in healthy pre-menopausal women (5). In contrast, tamoxifen acts as an estrogen agonist in the skeletons of postmenopausal women, despite its antiestrogenic effect in the breast. In postmenopausal women, tamoxifen increases lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) (6–8) and attenuates bone loss associated with chemotherapy-induced premature menopause (9). Use of tamoxifen is associated with decreases in markers of bone turnover (serum osteocalcin and urinary N-telopeptide [NTX]); moreover, the decline in NTX has been correlated with an increase in spine BMD after 12 months of treatment (10).

Because discontinuation of tamoxifen use is recommended after up to 5 years of therapy, we hypothesized that postmenopausal women who stop taking tamoxifen would experience a rapid decline in BMD and increase in bone turnover, similar to that seen after withdrawal of estrogen therapy. Before the current study, data on the skeletal effect of discontinuing tamoxifen treatment were available only from measurements of lumbar spine BMD in 11 patients, in whom spine BMD decreased 4.8% ± 2.5% within 1 year after they had stopped such treatment (11). Therefore, we initiated this investigation of lumbar spine, hip, and forearm BMD and bone turnover after tamoxifen withdrawal, and we undertook a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether administration of alendronate (70 mg weekly) would prevent any bone loss associated with discontinuation of tamoxifen therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Subjects

We recruited postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer who were receiving care at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center (CPMC) or Harlem Hospital Center (HHC) in New York, New York. Eligible patients had completed at least 2 years of tamoxifen therapy and were withdrawn from this treatment as part of their routine clinical care. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pre-menopausal state (because of documented deleterious effects of tamoxifen on bone in premenopausal women) (5); (2) treatment with an aromatase inhibitor; (3) known or suspected metastatic disease; (4) concomitant hyperthyroidism, liver disease, acromegaly, Cushing syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple myeloma, Paget disease of bone, renal osteodystrophy, or osteomalacia; (5) treatment within 3 months before enrollment with androgen, estrogen, calcitonin, systemic corticosteroids, fluoride, bisphosphonates, vitamin D in dosages exceeding 800 IU/day, vitamin D metabolites, thiazide diuretics, or lithium; (6) adjustments in thyroid hormone dosages of more than 25 μg within 6 months before enrollment; (7) impaired renal function (serum creatinine level >2.0 mg/dL); (8) documented gastroesophageal reflux disease or peptic ulcer disease; and (9) allergy or intolerance to bisphosphonates.

Study Procedures

The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. After baseline measurements, the study subjects were randomly assigned, within 3 months after withdrawal of tamoxifen, to receive either orally administered alendronate (70 mg weekly) or an identical-appearing placebo. Supplementation of calcium intake (to a total of 1,200 mg daily) and of vitamin D (400 U daily) was recommended. All participants gave written informed consent for this protocol, which was approved by the institutional review boards of CPMC and HHC.

Densitometry was performed at baseline and at 12 months. BMD was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (QDR-4500 densitometer; Hologic Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts). The short-term in vivo precision error (root-mean-square standard deviation) was 0.010 g/cm2 for the L1-L4 vertebrae, 0.016 g/cm2 for the total hip, 0.018 g/cm2 for the femoral neck, and 0.013 g/cm2 for the forearm. Two dedicated full-time x-ray technicians (certified by the International Society of Clinical Densitometry) performed all scans. Scans of phantoms were used to assess the machines for detector drift on a daily basis.

Serum (morning collection) and 24-hour urine samples were collected at baseline and at 12 months. Serum calcium, albumin, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase were measured by autoanalyzer (Olympus AU2700; Olympus Ltd, London, England). Urine samples were quantified and stored at −70°C for batch analysis of NTX by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Wampole Laboratories, Inc., Princeton, New Jersey).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses employed repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with treatment groups as categories and pretreatment/posttreatment as times. Our initial power calculations, based on a hypothesized between-group difference in lumbar spine BMD of 5% with a within-population SD of 5%, showed that we would need 17 evaluable study subjects per group to achieve 80% power (α = .05) in an unpaired t test analysis. SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) or Microsoft Excel was used for all analyses. All results are reported as mean values ± SEM.

RESULTS

Patient accrual was substantially limited by the introduction of aromatase inhibitors (12), which are now routinely used in patients discontinuing tamoxifen therapy at our medical center.

The study group consisted of 11 patients, who were randomly assigned to receive alendronate (n = 6) or placebo (n = 5) for 1 year. At baseline, the study subjects had a mean age of 58 ± 2 years old and were 11 ± 2 years past menopause. Of the 11 patients, 10 were recruited from CPMC and 1 was from HHC. Five participants were Hispanic, 4 were white, 1 was African American, and 1 was of East Asian descent. No patient withdrew from the study. There were no differences in age or baseline BMD at any measured anatomic site between the 2 groups. Baseline T-scores were as follows: lumbar spine, −1.1 ± 0.4; total hip, −0.4 ± 0.3; femoral neck, −0.7 ± 0.3; and distal radius, −0.3 ± 0.4. Despite the small sample size, differences in BMD and bone turnover were evident.

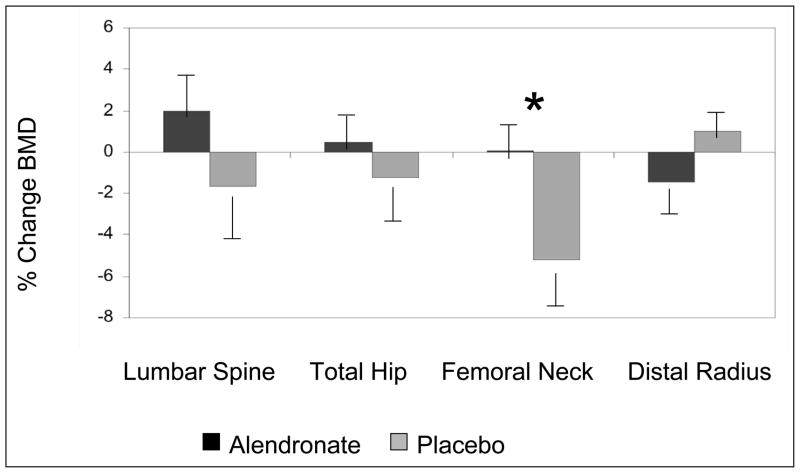

To protect against inflation of type I error attributable to the multiplicity of comparisons conducted on the same subjects, we used an omnibus initial multivariate ANOVA model that included all 4 BMD sites as dependent variables. Because this model showed an overall significant effect of treatment group (P < .05), further general linear models with least squares means for individual BMD sites were pursued. The treatment group had a significant effect on change in femoral neck BMD from baseline (P = .02). Withdrawal of tamoxifen was associated with a significant 5.2% (0.040 g/cm2) decline in BMD from baseline at the femoral neck (P < .01), which appeared to be prevented by weekly administration of alendronate (Fig. 1 and 2). Changes seen at other anatomic sites did not reach statistical significance in further ANOVA models. Adjustment for baseline BMD did not affect results at any BMD site.

Fig. 1.

Change in bone mineral density (BMD) 1 year after withdrawal of tamoxifen in the alendronate- and placebo-treated study groups. *The treatment group had a significant effect only on change in femoral neck BMD from baseline (P = .02). Results are shown as mean values ± SEM.

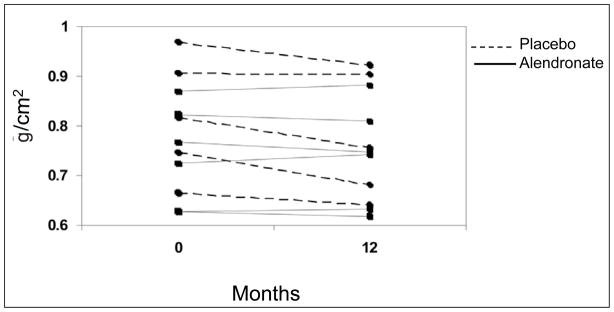

Fig. 2.

Change in bone mineral density at the femoral neck during the 12-month study period, shown for each patient in the alendronate- and placebo-treated study groups.

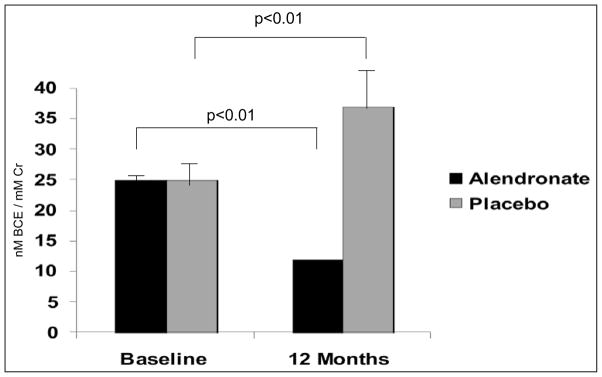

In similar analyses, the treatment group also had a significant effect on change in urinary NTX from baseline (P < .001). Despite identical baseline urinary NTX levels in the 2 study groups (Fig. 3), 12 months after discontinuation of tamoxifen therapy, NTX levels increased by 48% in study subjects in the placebo group (25 ± 4 to 37 ± 6 nmol bone collagen equivalents/mmol creatinine; P < .01), whereas weekly alendronate treatment was associated with a significant 52% decline (25 ± 2 versus 12 ± 1 nmol bone collagen equivalents/mmol creatinine; P < .01) in this bone resorption marker (Fig. 3). Adjustment for baseline urinary NTX did not affect these results.

Fig. 3.

Urinary N-telopeptide at baseline and 1 year after withdrawal of tamoxifen in the alendronate-and placebo-treated study groups. The treatment group had a significant effect on change in urinary N-telopeptide from baseline (P < .001). Bracket lines and P values describe within-group change from baseline. Results are shown as mean values ± SEM. BCE = bone collagen equivalents; Cr = creatinine.

Serum calcium levels were unchanged during the course of the study. Serum albumin concentrations remained at 4.0 g/dL or more in all study subjects. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels increased slightly within the reference range in the placebo group (71 ± 12 to 82 ± 10 U/L; P = .05). Changes in these serum measurements were unaffected by adjustment for baseline values.

DISCUSSION

We undertook this study of bone mass and bone turnover after withdrawal of tamoxifen treatment at a time when the standard of care dictated no further therapeutic intervention after tamoxifen for many patients with breast cancer. After initiation of the study, the introduction of aromatase inhibitors altered treatment patterns at our institution, making continued enrollment of patients in this study impossible. Nonetheless, and in an admittedly statistically underpowered study, we found significant differences between the treatment and control groups.

Withdrawal of tamoxifen led to a significant decrease in femoral neck BMD in a small group of patients. These results extend those of Resch et al (11), who found a significant decrease in spine BMD after discontinuation of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. We also found that urinary NTX, a marker of bone resorption, increases after withdrawal of tamoxifen, a finding that supports our hypothesis that the decline in BMD seen after withdrawal of tamoxifen is similar in character to that associated with withdrawal of estrogen. Consistent with the increase in bone turnover implied by these results, total alkaline phosphatase levels tended to increase in the placebo group. In addition, this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial provides the first data supporting possible benefits of bisphosphonate therapy after withdrawal of tamoxifen treatment in post-menopausal women with a history of breast cancer.

As a result of our study design, patients receiving aromatase inhibitors after tamoxifen therapy could not be included in the current trial. The nonsteroidal (anastrozole and letrozole) and steroidal (exemestane) aromatase inhibitors reduce the production of estrogen (12). Thus, their use could have been predicted to have a negative effect on bone health. In a large study (N = 8,010) that compared letrozole versus tamoxifen for adjuvant treatment of breast cancer in postmenopausal women, after a median of 26 months, the frequency of fractures was higher in the letrozole-treated group (5.7% versus 4.0%; P < .001) (13). Another study compared the results with use of anastrozole versus tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. After a median of 47 months, anastrozole therapy was also associated with increased fracture risk (7.1% versus 4.4%; P < .001) (14). Although use of tamoxifen was associated with small gains in BMD, a 2-year period of anastrozole treatment was associated with a 4.0% decrease (P < .001) in spine BMD and a 3.2% decrease (P < .001) in total hip BMD (15). Markers of bone turnover were increased with anastrozole use and decreased with tamoxifen therapy (15). Femoral neck bone loss was also documented when exemestane treatment was compared with placebo (16). Significantly increased rates of fractures were not found in studies that compared exemestane versus placebo (16) or tamoxifen (17) or in a study that compared letrozole with placebo used after tamoxifen therapy (18). A shorter follow-up time (≤30 months) may have limited the ability of these studies to discern a significant difference in fracture rates. A recent study has shown that lumbar spine bone loss could be prevented when biannual zoledronic acid infusion was initiated together with letrozole therapy (19). Further data from other clinical trials of zoledronic acid in these patients are becoming available. Overall, these data from studies of aromatase inhibitors, used as initial therapy or after withdrawal of tamoxifen, raise further concern for the skeletal integrity of women receiving adjuvant treatment for breast cancer and support consideration of intervention to prevent bone loss in this setting.

CONCLUSION

This study, despite its limited sample size, documents a decline in BMD after withdrawal of tamoxifen. The data suggest that all postmenopausal women with breast cancer completing tamoxifen therapy should undergo an evaluation of their skeletal health. The data also provide proof of principle supporting the consideration of bisphosphonate therapy to prevent bone loss in these patients. Other clinical factors, such as age, risk of falling, and baseline BMD, will obviously be important to consider in treatment decisions. Intervention to prevent bone loss may be even more critical in the future, as more patients are given aromatase inhibitor therapy after withdrawal of tamoxifen treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the Avon Foundation and by grant K24 DK074457 from the National Institutes of Health. Merck & Co. supplied drug and placebo pills under the Medical School Grant Program.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BMD

bone mineral density

- CPMC

Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center

- HHC

Harlem Hospital Center

- NTX

N-telopeptide

Footnotes

Part of this work was presented in abstract form and as a poster presentation at the 27th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; September 23-27, 2005; Nashville, Tennessee.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Powles T, Paterson AH, Ashley S, Spector T. A high incidence of vertebral fracture in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1179–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delmas PD, Fontana A. Bone loss induced by cancer treatment and its management. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:260–262. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valagussa P, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Bonadonna G. Long-term sequelae from adjuvant chemotherapy. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1993;127:247–255. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-84745-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minton SE, Munster PN. Chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea and fertility in women undergoing adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Cancer Control. 2002;9:466–472. doi: 10.1177/107327480200900603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powles TJ, Hickish T, Kanis JA, Tidy A, Ashley S. Effect of tamoxifen on bone mineral density measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in healthy pre-menopausal and postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:78–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Love RR, Mazess RB, Barden HS, et al. Effects of tamoxifen on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:852–856. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199203263261302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turken S, Siris E, Seldin D, Flaster E, Hyman G, Lindsay R. Effects of tamoxifen on spinal bone density in women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1086–1088. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.14.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen B, Ejlertsen B, Dalgaard P, et al. Tamoxifen and bone metabolism in postmenopausal low-risk breast cancer patients: a randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:992–997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headley JA, Theriault RL, LeBlanc AD, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Hortobagyi GN. Pilot study of bone mineral density in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Invest. 1998;16:6–11. doi: 10.3109/07357909809039747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marttunen MB, Hietanen P, Tiitinen A, Ylikorkala O. Comparison of effects of tamoxifen and toremifene on bone biochemistry and bone mineral density in post-menopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1158–1162. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.4.4688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resch A, Biber E, Seifert M, Resch H. Evidence that tamoxifen preserves bone density in late postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1998;37(7–8):661–664. doi: 10.1080/028418698430007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for post-menopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:619–629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thürlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, et al. (Breast International Group [BIG] 1–98 Collaborative Group) A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in post-menopausal women with early breast cancer [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2200] N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2747–2757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, et al. (ATAC [Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination] Trialists’ Group. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer: results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) trial efficacy and safety update analyses. Cancer. 2003;98:1802–1810. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eastell R, Hannon RA, Cuzick J, Dowsett M, Clack G, Adams JE (ATAC Trialists’ Group) Effect of an aromatase inhibitor on BMD and bone turnover markers: 2-year results of the Anastrozole, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial (18233230) J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1215–1223. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lonning PE, Geisler J, Krag LE, et al. Effects of exemestane administered for 2 years versus placebo on bone mineral density, bone biomarkers, and plasma lipids in patients with surgically resected early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5126–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. (Intergroup Exemestane Study) A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in post-menopausal women with primary breast cancer [published corrections appears in N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2461 and N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1746] N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. Randomized trial of letrozole following tamoxifen as extended adjuvant therapy in receptor-positive breast cancer: updated findings from NCIC CTG MA.17. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1262–1271. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brufsky A, Harker WG, Beck JT, et al. Zoledronic acid inhibits adjuvant letrozole-induced bone loss in post-menopausal women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:829–836. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]