Abstract

We performed a retrospective observational study of thirty-four persons with late onset of Huntington Disease (HD) (onset range 60-79 yrs). CAG trinucleotide expansion size ranged from 38 – 44 repeats. Even at this late age a significant negative correlation (r= -0.421, p< 0.05) was found between the length of repeat and age of onset. Important characteristics of these older subjects were: (1) Most (68%) were the first in the family to have a diagnosis of HD, (2) Motor problems were the initial symptoms at onset, (3) Disability increased and varied from mild to severe (4) Disease duration was somewhat shorter (12 yrs) than that reported for mid-life onset, (5) Death was often related to diseases of old age, such as cancer and cerebrovascular disease, (6) Serious falls were a major risk and (7) Global dementia may be associated with coincident Alzheimer disease. Recognizing these characteristics will help physicians and other health care providers better identify and follow the late onset presentation of this disease.

Keywords: Huntington Disease, late onset, Neurogenetics, CAG repeat expansion

Introduction

Huntington disease (HD) is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disorder with considerable variability in clinical manifestations and age at which symptoms first appear. Typical age at onset of symptoms is in the 40s1. The cause is a gene mutation in chromosome 4 with a CAG trinucleotide repeat of 35 or greater2. Repeat size can expand or contract with the next generation. The duration from symptom onset until death is typically 15 to 20 years3,4. There is no cure or treatment to postpone progression of the disease. Symptom management is currently the mainstay of treatment.

Our HD Center and Neurogenetics clinics have evaluated more than 500 families with this disease. Since the availability of direct DNA testing 15 years ago, we have observed an increasing number of patients diagnosed at a later age. HD with late onset has several characteristics worthy of emphasis.

Here we report a retrospective observational study of 34 cases with onset of HD symptoms at the age of 60 years and older and review the clinical characteristics and natural history of their disease.

Methods

Subjects attended the University of Washington and Seattle VA Medical Centers' Neurogenetics and HDSA Center of Excellence clinics. Thirty-four persons were found to have onset age of 60 years or later. The following information was extracted from subject's medical records: age of symptom onset (based upon a best estimate of when family, friends and the patient first noticed motor, behavior or psychiatric symptoms), nature of symptoms at onset, course of illness (most patients were seen annually), duration of symptoms (until death or current), family history of HD or related disorders, DNA test result, clinical and social issues and the cause of death. Fourteen subjects have been evaluated one or more times with the Unified HD Rating Scale ′995. We reviewed the results of the Motor, Independence and Functional Capacity Scales. The Motor scale evaluates chorea, dystonia, gait, coordination and eye movements with the score ranging from no findings (0) to maximum findings (124). The Independence scale rates overall abilities from total bed care (10) to full independence with no special needs (100) with increments of 5 points. The Functional Capacity scale measures abilities for occupation, finances, domestic chores, care level and activities of daily living and ranges from no functional capacity (0) to fully functional (13). This record review study was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Results

Thirty-four persons were identified with age at onset of HD symptoms between 60 and 79 (mean age 66). (see Table 1) All were diagnosed with symptomatic HD by an experienced neurologist. There were 20 males and 14 females. All were Caucasian (one Hispanic). Nine patients have died, and seven have been lost to follow up. The range of disease duration was between 2 and 17 years, the oldest living to age 91. The 34 cases were from thirty-one different pedigrees. Eleven of the cases had a family history of HD, with average age of onset in the family being 60 years. Twenty-three persons (68%) were the first case of HD identified in the family. Suggestive but non-specific past family history sometimes included psychiatric institutionalization, Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease (AD), multi-infarct dementia, multiple sclerosis, movement disorder of unknown type, nervousness, or early death in a parent from suicide or trauma.

Table 1. Characteristics of Late Onset HD Cases (n = 34).

| Gender | Family history of HD | Onset age (years) | Avg age at onset in family | Symptoms at Onset | Assist. Living/NH | Driving | Age at Death (n=9) | Duration (yrs) | CAG repeat size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 males (59%) 14 females |

Yes (11) No (23: 68%) |

Mean 66 (Range 60–79) | 60 yr | Motor (34) (Chorea (29)) Cognitive (10) Psychiatric (11) |

10 (29%) | 11 (32%) | Mean 81yrs (range 71–91) | To death (n=9): Mean 12 Range 7- 20 Living (n=18): Mean 9.4 yrs Range 2 – 17 (7 subjects lost to follow up) |

Mean 41.0 (Range 38 – 44) |

NH: Nursing Home

All cases had mild motor symptoms at onset (Table 1). The most common motor disturbance was mild chorea (n=29, 85%). Other types of motor problems included coordination difficulty (6), deterioration in handwriting (3), and voice change (1). Ten cases (30%) also had cognitive problems at onset, and seven had mild memory loss. Eleven cases (33%) reported early psychiatric problems such as anger (2), paranoia (1), depression (3), psychosis (1), apathy (3), and panic attacks (1). Some patients came to the HD clinic with initial diagnoses of Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, or schizophrenia. Fifteen subjects were initially evaluated with the UHDRS scale one to five years after symptom onset (Table 2). Mean Motor score was 34, mean Independence score was 84, and mean Functional Capacity score was 9. These scores are indicative of mild to moderate disease.

Table 2. Summary of selected UHDRS parameters at onset (n=15).

| UHDRS Assessment | Score | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Motor | Mean: 34 Range: 13-64 |

Best: 0 Worst: 124 |

| Independence | Mean: 84 Range: 55-90 |

Best: 100 Worst: 10 |

| Functional Capacity | Mean: 9 Range: 6-13 |

Best: 13 Worst: 0 |

Thirty subjects (88%) have been seen more than once and symptom progression was slow but always occurred and included worsening of chorea, tendency for falls (postural instability), cognitive decline with memory loss, and further psychiatric difficulties such as irritability, impulsivity, anxiety, insomnia and psychosis (delusions and hallucinations). This progression often required assisted living arrangements or nursing home placement which occurred in 10 subjects (29%). Eleven subjects (32%) were still driving at the time of their most recent evaluation.

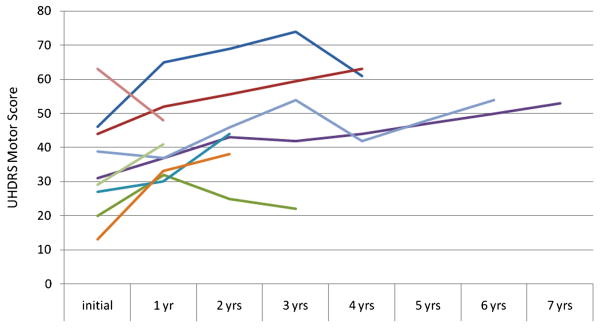

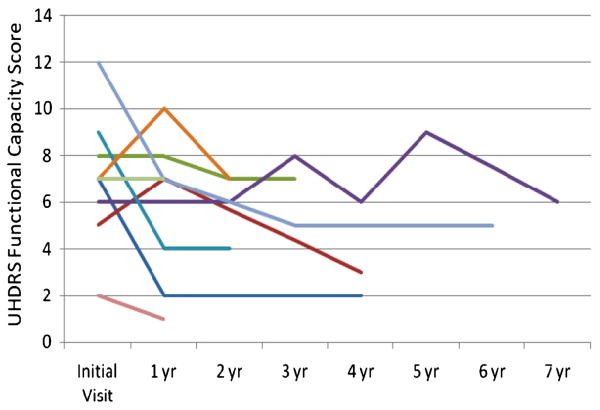

Nine subjects had one or more additional evaluations with the UHDRS (see Figures 1 and 2). Eight of the nine had worsening of the Motor score over time. One subject's score improved from 63 to 48 after one year. This was largely a result of a decrease in chorea on medication. However, she had muscle rigidity, had to use a wheelchair and had low overall Functional Capacity. Three subjects had some improvement in scores after one or more years of worsening. This correlated with some improvement in chorea. However, their Independence and Functional Capacity scores continued to decline.

Figure Legend 1.

Longitudinal UHDRS Motor scores in nine late onset subjects. Individual subjects indicated by colored lines are the same in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure Legend 2.

Longitudinal UHDRS Functional Capacity scores in nine late onset subjects. Individual subjects indicated by colored lines are the same in Figures 1 and 2.

Nine subjects have died thus far with a mean disease duration of 12 years. The causes of death included aspiration pneumonia (2), cancer (2), fall with head trauma (2), stroke (1), GI bleed (1) and perforated bowel (1). Three cases with progressive memory loss resulting in global dementia had brain autopsy, two at age 85, and one at age 91. All three showed Alzheimer disease changes in addition to HD. One also showed bilateral infarcts.

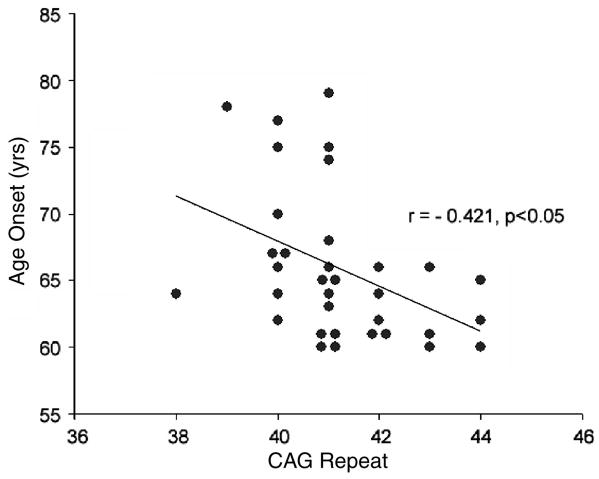

DNA testing was completed in all 34 cases with CAG repeat sizes ranging from 38 – 44 with a mean of 41.0 (Figure 3). A significant negative correlation (r=-0.421, p< 0.05) was found between age of onset and CAG repeat size. The two subjects with latest onset (79 and 78 years) had 41 and 39 CAG repeats respectively. The subject with the lowest repeat expansion of 38 had onset at age 64 years.

Figure Legend 3.

Age at Onset vs. CAG expansion size scatterplot with linear regression line for 34 subjects.

Typical Case Vignettes

Mild Disease

Subject 1 was a 89 year old retired male World War II Veteran who had the onset of mild chorea at the age of 78 years. He had no family history of neurologic disease. His father, who died at the age of 80 years, was described as “fidgety”. DNA testing for HD showed 39 CAG repeats. The subject was evaluated yearly, using UHDRS, over a period of 7 years. Initial motor score at age 80 was 31. Symptoms were primarily motor and gradually declined to the most recent motor score of 53 at age 89. Behavioral and cognitive function showed mild irritability only. He lived at home, was independent in all activities of daily living, could walk without assistance and still drive (after passing a formal driving test). He and his wife considered his most serious disability to be deafness.

Moderate Disease

Subject 2 was a 74 year old male college educated professional with the onset of mild chorea, a change in his voice, balance problems, restlessness, and personality change at the age of 61. He had no family history of neurologic disease. His father was said to be “fidgety” and cognitively normal until his death at age 61. DNA testing for the HD gene showed 41 CAG repeats. He was evaluated yearly using the UHDRS, over a period of 4 years. Initial motor score at age 68 was 39. Symptoms were motor, including mild chorea and dysphagia, slight gait disturbance, mood changes such as irritability and verbal aggression, and declined to the most recent motor score of 54 at age 73. Cognitive function declined until he was no longer able to work at age 70. Chorea, impaired balance, restlessness, irritability and physical/verbal aggression worsened and required medication. Independence scale score of the UHDRS declined from 95 at first evaluation to 65 five years later. He continues to live at home with his wife. Although he has a similar UHDRS Motor Score compared to Subject 1 (with mild disease), this subject is more impaired overall because of his behavioral and psychiatric symptoms.

Severe Disease

Subject 3 was a 74 year old retired male who had the onset of mild chorea, memory problems and anxiety at age 61. He had no known family history of Huntington disease. His father died from a gunshot wound at age 50. His paternal uncle was said to have dementia and his paternal grandfather had a staggering gait. His mother died in her 60s from emphysema, and his maternal grandmother was said to have Parkinson disease. DNA testing for the HD gene showed 43 CAG repeats. He was evaluated yearly for four years, using the UHDRS, until he developed psychosis with paranoid features and refused to continue testing. Initial motor score at age 66 was 45. Symptoms were motor with chorea and some mild dystonia, cognitive problems, and mild depression. He lived independently with regular visits from his daughter. Over the next several years, his self care and psychiatric function declined, he moved in with his daughter, then moved to assisted living, and finally full nursing home care. His behavior became a serious problem. He had three psychiatric hospitalizations, the first for depression and suicidal thoughts. The next two hospitalizations were for psychosis, including delusions and hallucinations. Independence scale score (UHDRS) went from 80 at initial evaluation to 65 four years later and Functional Capacity declined from 7 to 2. Motor score was 61 at the four year evaluation, largely due to Parkinsonian features and dystonia. Chorea had nearly disappeared. His last UHDRS exam was at age 70 years. Now at age 75 he has deteriorated further but has refused additional testing.

Discussion

This study represents the largest collection of persons with late onset HD (≥60 years) who have had clinical evaluation, longitudinal follow-up and DNA genotyping. Our series of 34 cases of late onset demonstrated several features that deserve emphasis (Table 3). This group always presented with mild motor disturbance, often chorea, sometimes accompanied by changes in behavior. None of these symptoms were initially disabling. James et al reported common early mild motor disturbance in a review of persons with HD onset over age 60 listed in the HD register from New South Wales6. They noted that early disability from cognitive problems might have been masked by retirement from work.

Table 3. Important Features of Late Onset HD.

|

The cognitive abnormality usually associated with HD typically consists of poor attention span, impaired judgment, reduced verbal fluency and poor executive function. Memory, orientation, recognition and conversational ability are usually intact. Three subjects in the present study eventually developed a more global dementia that was seriously debilitating. It is of interest that at autopsy all three had AD in addition to HD, emphasizing the importance of coincident medical and neurological disorders in this population. On the other hand, Burger reported a patient with an initial diagnosis of AD who was subsequently found to have HD7.

The CAG repeat sizes in this study were larger than anticipated with a mean of 41.0. Only two persons had repeat sizes below 40 and 6 had scores of 43 or 44. James et al described CAG repeats all below 40 in ten cases of late onset HD4. Kremer et al noted that in persons beyond the age of 60, the effect of the CAG repeat length on age of onset seemed to diminish8. However in our study, even in this older population, the CAG repeat length showed a negative correlation with age of onset, consistent with the literature showing length of CAG repeat as an important factor influencing onset9,10. The 2 subjects with latest onset had different repeat sizes of 39 and 41. The smallest reported (and generally accepted) repeat size associated with symptoms is 34 with onset age of 60 years11.

The overall presentation of HD was considered to be initially mild by most families in this study, but progression in motor and/or behavior symptoms eventually occurred in all 30 subjects evaluated more than once. Disability varied from mild to severe as highlighted by the case vignettes. 10 subjects (29%) required assisted living or nursing home placement. Duration of disease (12 yrs) in the nine deceased subjects was shorter than that of persons with typical onset in mid-life which is usually reported to be 15-20 years. This is a small number of subjects, but is consistent with Foroud et al and Roos et al who reported HD duration was shorter in those with late onset of symptoms3,4. The disease was especially challenging to caregivers when dementia or behavioral problems were present.

Eleven subjects (32%) in this study were still driving at the time of the most recent evaluation. Patients with HD in this age group should be advised against driving and carefully monitored if they continue to drive. The issues in our society concerning driving and neurological diseases have been extensively discussed in the literature12, 13.

Five of nine subjects died from other diseases associated with aging such as cancer and vascular disease rather than from complications of HD. Two deaths from falls revealed the value of fall prevention to reduce traumatic brain injury and further disability. Grimbergen completed a detailed analysis of falls in persons with HD and suggested a relation to cognitive decline14. Coincident Alzheimer disease may exacerbate this phenomenon.

It is important that many of these subjects were the first in the family to receive an HD diagnosis. In a study of HD prevalence in New South Wales, McCusker found 8% of the entire HD population with no family history15. In the present study 68% (23/34) of the subjects had no known family history of HD. The frequent lack of a clear family history of HD in this series is undoubtedly related to the small CAG repeat size occurring in other family members16, 17. Although the expansion tends to remain about the same size in affected persons in such families there is always the possibility of further expansion and concomitant earlier onset. Each child of the subjects in the present study are at 50% risk to inherit the HD mutation.

Kremer has summarized the general assessment of late onset HD as a condition in which the manifestations “are often surprisingly mild---and in these patients the disease will follow a slower progression than usual.”1 Our review of 34 late onset HD subjects suggests that although the initial manifestations are usually mild, the disease does progress and some cases develop severe disability requiring assisted living or full nursing home care. This substantial variability in clinical course must be kept in mind when evaluating and counseling these patients and their families.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs research funds and the Huntington's Disease Society of America. Our appreciation to our colleagues and the staff of the Medical Genetics clinic at the University of Washington for identifying late onset cases. Thanks to DG Cook and S Elmore for assistance with the figures.

References

- 1.Kremer B. Clinical neurology of Huntington's disease. In: Bates G, Harper P, Jones L, editors. Huntington's Disease, Third Edition Oxford Monographs on Medical Genetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huntington Disease Collaborative Research Group. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable in Huntington disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roos R, Hermans J, Vegter-van der Vlis M, van Ommen G, Bruyn G. Duration of illness in Huntington's disease is not related to age at onset. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:98–100. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foroud T, Gray J, Ivashina J, Conneally M. Differences in duration of Huntington's disease based on age at onset. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:52–56. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahant N, McCusker EA, Byth K, Graham S The Huntington Study Group. Huntington's Disease: Clinical correlates of disability and progression. Neurol. 2003;61:1085–1092. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000086373.32347.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James CM, Houlihan GD, Snell RG, Cheadle JP, Harper PS. Late-onset Huntington's disease: a clinical and molecular study. Age and Ageing. 1994;23:445–448. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger K. Late onset Huntington disease – a differential diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Nervenartz. 2002;73:870–873. doi: 10.1007/s00115-002-1361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kremer B, Squitieri F, Telenius H, Andrew SE, Thielmann J, Spence N, Goldgerg YP, Hayden MR. Molecular analysis of late onset Huntington disease. J Med Genet. 1993;30:991–995. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.12.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkman RR, Mezei MM, Theilmann J, Almquist E, Hayden MR. The likelihood of being affected with Huntington disease by a particular age, for a specific CAG size. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1202–1210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenblatt A, Liang KY, Zhou H, Abbott MH, Gourley LM, Margolis RL, Brandt J, Ross CA. The association of CAG repeat length with clinical progression in Huntington disease. Neurology. 2006;66:1016–1020. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000204230.16619.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrich J, Arning L, Wieczorek S, Kraus PH, Gold R, Saft C. Huntington's disease as caused by 34 CAG repeats. Mov Disord. 2008;23:879–881. doi: 10.1002/mds.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott BR, Heindel WC, Papandonatos, Festa EK, Davis JD, Daiello LA, Morris JC. A longitudinal study of drivers with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1171–1178. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000294469.27156.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uc EY, Rizzo M. Driving and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cuur Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8:377–83. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimbergen Y, Knol M, Bloem B, Kremer B, Roos R, Munneke M. Falls and gait disturbances in Huntington Disease. Mov Dis. 2008;23:970–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCusker E, Casse R, Graham S, Williams D, Lazarus R. Prevalence of Huntington disease in New South Wales in 1996. Med J Austr. 2000;173:187–190. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb125598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kartsaki E, Spanaki C, Tzagournissakis M, Petsakou A, Moschonas N, MacDonald M, Plaitakis A. Late Onset and typical Huntington disease families from Crete have distinct genetic origins. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird TD, Lipe HP, Steinbart EJ. Geriatric neurogenetics: oxymoron or reality? Arch Neurol. 2008;65(4):537–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]