Abstract

Purpose: This study's purpose was to advance the process of culture change within long-term care (LTC) and assisted living settings by using participatory action research (PAR) to promote residents’ competence and nourish the culture change process with the active engagement and leadership of residents. Design and Methods: Seven unit-specific PAR groups, each consisting of 4–7 residents, 1–2 family members, and 1–3 staff, met 1 hour per week for 4 months in their nursing home or assisted living units to identify areas in need of improvement and to generate ideas for community change. PAR groups included residents with varied levels of physical and cognitive challenges. Residents were defined as visionaries with expertise based on their 24/7 experience in the facility and prior life experiences. Results: All PAR groups generated novel ideas for creative improvements and reforms in their communities and showed initiative to implement their ideas. Challenges to the process included staff participation and sustainability. Implications: PAR is a viable method to stimulate creative resident-led reform ideas and initiatives in LTC. Residents’ expertise has been overlooked within prominent culture change efforts that have developed and facilitated changes from outside-in and top-down. PAR may be incorporated productively within myriad reform efforts to engage residents’ competence. PAR has indirect positive quality of life benefits as a forum of meaningful social engagement and age integration that may transform routinized and often ageist modes of relationships within LTC.

Keywords: Institutional care, Ageism, QOL, Age integration, Competence, Helplessness

Nursing homes and other long-term care (LTC) institutions have been the subject of extensive and growing attention and criticism from the public at large, popular media and scholars concerned about care and quality of life (QOL) issues of older people. In addition to questionable standards of medical care within nursing homes (Kayser-Jones, Beard, & Sharpp, 2009; Weiner & Hanlon, 2001), critiques have focused on the excessive medicalization of daily regimens that give relatively little attention to the realities of residents’ lives beyond their physical care needs (Foner, 1993; Gubrium, 1976; Kayser-Jones, 1990; Thomas, 1996); systematic dehumanization and infantilization of residents (Kayser-Jones, 1990; Vladeck, 1980); and problematic work conditions, compensation, and lack of benefits for nurses assistants (Diamond, 1986, 1992; Kalleberg, Reskin, & Hudson, 2000). These social dynamics and settings suppress recognition and nurturance of older adults’ potentials for lifelong learning, growth and contribution (Barkan, 2003; Dannefer & Shura, 2008; Dannefer, Stein, Siders, & Shura, 2008; Thomas, 2004), and reify cultural belief systems of ageism and age-related stigmatization that legitimize older adults’ isolation (Butler, 2002/1975; Dannefer & Shura, 2009). Many criticisms of institutionalized LTC for elders have synergy with Erving Goffman's definition of a “total institution” as a social setting of aggregate living and work that is cut off from broader society, which is marked by strictly regimented schedules and minimal opportunities for individuals to deviate from centrally administered routines and expectations (Goffman, 1961). This structure imposes formidable constraints on elders’ experiences within LTC.

Over the past several years, these concerns have fueled a number of significant reform efforts within LTC (for a review, see Rahman & Schnelle, 2008). These include efforts to change the culture within nursing homes by altering immediate nursing home environments to create a more humane habitat replete with pets, plants, and young people (e.g., the “Eden Alternative”—see Thomas, 1996; Thomas & Johansson, 2003); transformations according to a neighborhood concept and inclusion of on-site intergenerational centers (e.g., “Providence Mount St. Vincent”—see Anderson, 2008; Boyd, 2003); and recent Green House ® (Cutler & Kane, 2009; Rabig, Thomas, Kane, Cutler, & McAlilly, 2006) and Small House (Rabig, 2009) projects that entail major structural and architectural changes in order to provide more home-like experiences for elders and family-like relationships between care staff and residents. More general approaches to reforming experiences in later-life and related care issues are advocated by organizations such as the Pioneer Network (Fagan, 2003) and Wellspring (Weiner & Ronch, 2003) and evident in attempts to broaden and reframe discussion of later-life care options to include aging in communities in spite of public policy that currently promotes institutionalization (Thomas & Blanchard, 2009).

Although few formal evaluations of culture change in LTC have been reported (Rahman & Schnelle, 2008), some studies have provided evidence for improvements in older adults’ health and QOL and for organizational processes and relationships in residential LTC settings (Calkins & Marsden, 2000; Cutler & Kane, 2009; Dannefer & Stein, 2000; Dannefer et al., 2008; Thomas, 1996). To date, studies of culture change efforts have documented improvements in medication reduction (Thomas, 1996), in degree of choice about daily activities such as bathing and the time of getting up in the morning (Barrick, Rader, Hoeffer, Sloane, & Biddle, 2008; Dannefer & Stein, 2000; Kane, Lum, Cutler, Degenholtz, & Yu, 2007; Weiner & Ronch, 2003), and in social engagement (Calkins et al., 2001; Dannefer & Stein, 2000). However, little evidence suggests that elders themselves have participated in the identification of areas in need of improvement within their LTC communities and in the development of culture change initiatives. In a noteworthy exception, Calkins, Kator, Wyatt, and Halliday (2009) ascertained nursing home residents’ views on ways to improve use of their immediate physical environment, which resulted in community changes such as giving the “right of way” to residents regarding elevator use. Generally, changes are made “on behalf” of older adult residents to promote their best interests and improve their QOL while leaving elders themselves out of change processes. The tension between reform imperatives and already existing bureaucratic structures and power hierarchies within LTC facilities—structures and hierarchies that position elders in the relatively most powerless and passive roles within the total institution—is not an unrecognized problem by pioneers in LTC reform, yet presents formidable theoretical, methodological, and existential challenges.

The purpose of this study is to advance the process of culture change within a LTC community by engaging residents as experts directly in the change process. Resident engagement and leadership in reforms can benefit the goals of culture change and can offer a means of addressing some of the fundamental problems of nursing home life that initially motivated reform efforts and that are central to the mission and vision of reform organizations, particularly what Eden Alternative founder Bill Thomas termed the “plague of helplessness” of nursing home residents (Thomas, 1996). Resident engagement in reform offers a means of addressing residents’ lack of structural opportunities to overcome helplessness and to demonstrate competence within their LTC communities.

We use the method of participatory action research (PAR) to engage the expertise and promote the competence of residents. Our study, entitled “Learning from Those Who Know,” consists of a model—including theoretical framework, method, and demonstration of this method's potential and utility in LTC settings—that incorporates residents’ experience and expertise into culture change by facilitating elders’ involvement, centrality, and leadership within community reform efforts. Others have recognized the abilities and skills of older adults through active involvement in the evaluation of community change as well as in research (Baker & Wang, 2006; Blair & Minkler, 2009; Doyle and Timonen, 2010; Israel et al., 2008; Jones, Auton, Burton, & Watkins, 2008; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Ray, 2007), although elders’ involvement in participatory research is still relatively uncommon (Blair & Minkler, 2009). The primary goals of PAR in this study are twofold: to address institutionalized elders’ helplessness by promoting their competence and simultaneously to facilitate positive organizational change in LTC. We assert that this model has the potential to help to flatten hierarchies within LTC, to transform the power structure by promoting cross-age relationships with elders that are not based on their roles as care recipients, and to promote more creativity regarding community change than opportunities afforded in prominent reform imperatives.

Background: Culture Change, Resident Engagement, and Human Needs

Culture change efforts start with the needs and life circumstances of residents. This emphasis is evident in the introduction of terms such as “person-centered or resident-centered care” (Kitwood, 1997; Koren, 2010), “person-directed care” (Anderson, 2008; White, Newton-Curtis, & Lyons, 2008), “individualized care” (Casper, O’Rourke, & Gutman, 2009), and “consumer-driven health promotion” (White-Chu, Graves, Godfrey, Bonner, & Sloane, 2009). Despite this, culture change reform efforts have placed little emphasis on the direct involvement of elders. This omission is significant because the provision of care and service to residents, who are arguably the key constituents of the institution, is the entire raison d’etre of LTC facilities and because core principles of culture change include knowing, understanding and listening to residents, and honoring their experiences and perspectives (Fagan, Williams, & Burger, 1997; Thomas, 1996). Thomas (1996) articulated the broad concerns of many reformers when he identified boredom, loneliness, and helplessness as the “three plagues” of nursing home life. The official vision statement and founding principles of the Eden Alternative call for their elimination (http://www.edenalt.org). “Boredom” in LTC contexts relates to a lack of opportunity to control the content of one's experience and a paucity of options for activity that an individual evaluates as desirable or deserving her attention. “Loneliness” indicates a lack of relatedness and social integration. “Helplessness” implies incompetence in matters of everyday life—loss of ability or lack of opportunities to demonstrate one's abilities. These three plagues correlate closely with three basic human needs articulated in self-determination theory in psychology—“autonomy,”“relatedness,” and “competence” (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2008). Nowhere in self-determination theory is it suggested that these needs atrophy with age; rather, they are understood as basic and universal components of health and vitality for all human beings. Self-determination theory thus offers a solid theoretical basis for Thomas's three-dimensional formulation.

This theoretical perspective is a useful analytic tool for evaluating culture change efforts, as prominent reform programs have not addressed these three human needs equally. Residents’ competence is relatively underdeveloped within reform agendas, whereas reforms have given more comprehensive attention to relatedness and autonomy. To recast this point in terms of Thomas's claims, reform efforts have done more to address the plagues of loneliness and boredom than they have the plague of helplessness of residents.

For example, some studies suggest increases in social engagement in communities in which culture change has flourished (Calkins et al., 2001; Dannefer & Stein, 2000), which can be considered an indicator of relatedness. Some research shows that an increase in individual choice making and control over one's routine has been advanced through culture change reforms (Dannefer et al., 2008; Kane, et al., 2007), which relates to the need of autonomy. Largely these changes are not resident directed because they do not offer residents meaningful opportunities to demonstrate their competence and take on roles as experienced, capable members of their community, including within reform processes. Even in Green Houses ®, a currently celebrated pinnacle of decentralized LTC reform (Cutler & Kane, 2009), no evidence suggests that the residents’ need for competence is incorporated into the program of reform. This poses existential and practical challenges for residents and reformers, and in part may be understood as based on pervasive cultural assumptions that question old people's abilities to engage meaningfully in research and community building (Blair & Minkler, 2009; Ray, 2007).

Thus, within logics of prominent culture change initiatives, elders in LTC are still constructed as largely passive, incompetent and dependent, and are chiefly characterized as care recipients rather than recognized as dynamic and capable experts in the areas of life, routines, and interpersonal relationships within LTC. This study's design and PAR methodology address this problem. This project's orientation to residents regarding their political and cultural location within LTC institutions is to define them as experts.

Design and Methods

PAR begins with recognition of social and institutional problems and need for change and enlists relevant parties to examine and improve current modes of social action (Israel et al., 2008; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Wadsworth, 1998; Whyte, 1989). In this project's research design, residents volunteer to participate in research groups (RGs) as experts who are uniquely qualified to offer distinct and sage perspectives on the LTC facility in which they live. PAR provides an opportunity for elders to take an active role, to contribute to the process of culture change directly, to demonstrate their competence (Doyle & Timonen, 2010), and to transcend largely imposed strictures of helplessness. This is achieved in collaboration with staff and family members and with the facilitation and support of researchers. Residents were invited to be visionaries focused on the tasks of identifying strengths and problems in their community and to develop ways to improve community life. Residents’ lived experiences of LTC, as well as their former life experiences (including a diverse array of trades; management and supervisory skills; parenting, grandparenting and caregiving skills; and medical and nursing expertise), are all considered assets to be recognized and engaged within this method. The method of PAR is distinct from focus groups because rather than serving as a forum through which a researcher extracts experiential and descriptive information from research participants according to predetermined questions, PAR engages participants as co-researchers who participate in the formulation of questions and research goals (Chenoweth & Kilstoff, 2002). This is integral to the broader PAR intent to foster collective stakeholders’ processes of identifying areas of interest and importance to them, to empower them to envision collectively alternate and improved community processes, and to support their collective action to communicate and implement their ideas.

Setting and Sample

This project was conducted at Judson at University Circle in Cleveland, Ohio, a continuing care retirement community (CCRC) that is designated as an Eden facility. The study was not designed to produce generalizable findings, but rather serves as an exploratory demonstration of what is possible through engaging elders in participatory research (Doyle & Timonen, 2010). Four units within the CCRC (including assisted living and nursing home units, and two specialized memory support units) were identified collaboratively by researchers and LTC administrators as in need of further improvements and at diverse points in the culture change process, and thus appropriate for this project. On each of these four units, solicitation of volunteer research participants was done through a process of informational meetings. These meetings were announced by fliers and mailings distributed to residents, staff, and next of kin. Researchers gave presentations to residents, staff, and family members to describe the project and invite participation. Afterwards, researchers spoke one-on-one with attendees to answer questions and generate lists of people interested in participating. Written informed consent was sought from all potential participants and, when required, from next of kin of residents.

Those for whom written consent was obtained were organized into seven unit-specific RGs, each consisting of a regular set of four to seven residents, one to two family members, and one to three staff. Two of these groups were in assisted living units, and the other five were in nursing home units. Each RG had two regular facilitators whose role was to encourage and mediate collective conversations about participants’ evaluations of aspects of their communities in need of improvement and their ideas for positive change; the facilitators’ role was neither to make specific suggestions nor to lead the RGs in specific directions, but to support the experts’ collective process of critique and vision. Each RG met on their unit for 1 hour per week continuously for four months. RGs included residents with varied levels of physical and cognitive challenges; no one was excluded from participation due to such challenges, including dementia. Efforts were made to create diverse groups with respect to gender, ethnicity, health status, and cognitive status. Although family members and staff of the community were invited to participate regularly, their attendance was far less than residents’ attendance in terms of number and regularity. The total PAR sample included 74 residents, staff, and family/friend participants (see Table 1). Of these, 53 were from the nursing home units and 21 were from assisted living units. More females than males participated in all categories, reflecting the gendered patterns of nursing home occupancy and of care work.

Table 1.

Research Group Sample Description (N = 74)

| Nursing home |

Assisted living |

Total |

||||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Residents | 28 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 37 | 12 |

| Staff | 12 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Family/friends | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Sub-total | 43 | 10 | 17 | 4 | ||

| Total | 60 | 14 | ||||

Note: Total PAR participants across 7 RGs.

Although attempts were made to include all people interested in participating for whom written consent was obtained, overall, more residents became interested in participating in RGs than our project had the resources to include. In addition to written consent, facilitators were diligent in seeking verbal consent for participation from each resident at the beginning of each RG meeting, honoring anyone's request to opt out of participation. This ongoing verbal consent process was not explicitly required by the human subjects’ protocol, yet it was enacted to ensure the voluntary nature of participation and to protect participants’ rights to not participate at any time, for any reason. Institutional Review Board review maintained that this procedure went above and beyond human subject protocol.

Although the structure of each RG was fairly consistent (comprised of the same set of 8–10 participants and 2 facilitators each week), the process in each group was emergent and depended greatly on its constituents. From the onset of participant recruitment through the denouement of all RGs, the premise that residents were the central members of the RGs due to their lived experience and expertise regarding LTC was reiterated by research facilitators within RGs, and residents were engaged as key stakeholders within their LTC communities regarding visions of what is done well and visions of positive change. Staff and family members were also engaged as key stakeholders in these communities with their own valid experience and expertise regarding LTC that is qualitatively distinct from residents’ views. Whereas residents held central roles in the PAR processes, staff and family participants held supportive and collaborative roles by adding their perspectives to emergent topics of interest and concern. Within the RGs’ collective processes, research facilitators consistently encouraged and mediated these diverse stakeholders’ discussions, reminded participants that their experiences and views are unique and important, and oriented them beyond complaints and toward generating ideas for positive change or collective action.

It is important to note that the goal of the use of PAR in this project was to encourage critical and collective reflection about ideas for community improvements within LTC through a structured process that engaged residents as leaders and visionaries along with staff and family members. Unlike formal PAR research designs, this project did not include highly formalized processes of goal setting, identification of data formats, and processes of collecting and reviewing specific forms of data. Rather, each RG's process was emergent and based on the interests and group dynamics among the participants. Thus, the project's method and design created a vehicle through which residents themselves could identify, discuss, and analyze areas in need of improvement in a collective forum, supported by staff and family members, and from these develop ideas for positive community change.

Results: Resident-Directed Culture Change Through PAR

Overall PAR processes fostered strengthened relationships among participants in all seven groups and resulted in various ideas and initiatives for community improvement. All groups generated ideas for positive change, several of which were implemented during the study. Themes that emerged across RGs included improving organizational practices; honoring accomplishments, capabilities and talents; strengthening relationships among residents, staff, and family within units; and providing new opportunities for meaningful social engagement. For example, one assisted living RG identified lack of personal knowledge of and sense of connectedness to staff as a problem. In their discussion, one resident suggested, and others quickly supported, the idea of soliciting and conducting informal personal interviews with all direct care staff in their unit to get to know more about them and their lives and to use this information to develop a “Staff Face Book” with biographical information and photos that would be shared with their unit and expanded over time. Their goal was to demonstrate that staff are valued community members. Within another RG, the paucity of civic engagement opportunities for residents, particularly residents with considerable mobility limitations and care needs, was identified as a problem. Members of this RG developed on-site volunteer service opportunities for assisted living residents to help local cultural and arts organizations with mailings. Within specialized memory support units, the challenges of empathy and communication between residents and staff were identified by two RGs as areas in need of consistent energy and improvement. Members of one RG brainstormed and tested together from week-to-week ways for staff to improve interpersonal communication with residents with severe dementia, including through sustained eye contact, smiles, and touch. One memory support unit RG shared informal “daily diaries” between residents, staff, and family participants in order to learn more about each other and to prompt discussion about differences in experiences within LTC. Another memory support unit RG discussed the idea of developing a theatrical play to improve understanding and empathy between residents and staff.

In the following sections, we present more detailed descriptions of four additional RG initiatives to illustrate the potentials of the RG model to nurture the diverse and proactive expression of creativity and resourcefulness on the part of residents and to enable them to contribute to positive community change. They are not intended to be representative of the rich and varied ideas and processes of the RGs. They are selected because each illustrates the central role of competence and contributions of residents in the PAR process and because they illustrate the diversity of PAR group processes in this project.

Improving Organizational Practices and Honoring Accomplishments: Residents’ Perspectives Inspire Practical Changes in Bulletin Boards

In a nursing home RG, residents noted that bulletin boards were placed too high on the wall for residents who use wheelchairs to see clearly and that the print of posted materials was too small to read for those with visual impairments. Regular postings included activities calendars, the Resident Bill of Rights, and birthday and memorial service announcements. They shared concerns that this limited residents’ access to information and sense of participation in the everyday life of the unit and needed to be changed. This concern has direct synergy with the Eden principle of culture change that emphasizes promotion of resident participation in daily activities within their LTC community (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, principle #4). The group invited the nurse manager to attend one of their meetings and discuss their concerns. The manager attended and agreed to pursue some of the issues raised. As a result, several postings were printed in larger font, and several bulletin boards were physically lowered. This RG also noted that positive news and artifacts representing residents’ accomplishments were rarely shared on bulletin boards. This concern was triggered by one resident sharing her artwork with others in the RG, and it relates to Eden principles of culture change that emphasize variety and spontaneity in daily life within LTC and that encourage decentralized and resident-led authority over decision making (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, #5 and #8). In response, the RG posted enlarged prints of her artwork on the bulletin boards throughout the unit. This resident had learned to paint while participating in the facility's arts program, and the group wanted to honor her new talent and share it with their community.

Improving Organizational Practices: Residents’ Practical Suggestions for Changes in Dining Experiences

In at least two RGs, the dining experience was identified as in need of improvement. In an assisted living RG, a resident noted that dinnertime was “loud and clangy” and that this environment made dining a very unpleasant experience three times a day. The group was then challenged to come up with ideas of how the dining experience could be more pleasant and home like. One resident noted that ambiance is key, and she mentioned how she always had a tablecloth and placemats (in contrast to paper ones) on her table at home, with flowers as the centerpiece. Others suggested that lighting could be dimmer so that residents and staff entering the dining room could feel as if they are eating in a nice restaurant and that couples who ate together should be able to have their own table lit with candlelight if they wanted. The group thought that changes in lighting may limit the noise that occurs in the brightly lit dining area. In addition, one resident suggested that residents assist staff in setting the tables, like the chores they had when they were younger. This idea resonates with the culture change principle that encourages residents’ participation in the daily activities that are necessary to maintain the home or community (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, #4). Because the Unit Manager was a member of this RG, she noted that these were practical suggestions that could be easily implemented to improve the dining experience on the unit, as soon as the next meal.

In a nursing home RG, the dining experience was described in different ways. One of the problems identified was that there was not enough space for residents who use wheelchairs to get around other residents sitting beside them. One resident stated, “The guy who designed this place has obviously never been in a wheelchair … we get all tangled up and can’t move around each other easily. I’ve said something to management about it, but no one took me seriously. Of course, the easy thing to do is to spread the dining room out into the hall during mealtime so we have room to move around.”

Ideas suggested by residents were not always consistent with the de-regimenting and deinstitutionalizing ethos of culture change. For example, a second problem related to dining concerned organizational information about the timing of meals. Although the schedule lists a dinnertime, residents in a nursing home RG noted the reality of when residents are escorted and served dinner is not consistent with the schedule. One resident noted that he had former experience in the Navy and that a clear whistle alerted the entire group when it was mealtime. He stressed that this minimized confusion, and he stated clearly that this method could work in the nursing home, noting that current practices indicated that “We’re sloppy in our operation here, let's put it that way.” Other residents agreed that this suggestion was a clever idea. This is interesting from the broad perspective of the culture change agenda because it seems to advocate an increase in institutional regimentation.

That point notwithstanding, such collectively generated ideas for improvement in the nursing home dining experience illustrate the culture change principle of de-emphasizing top-down bureaucratic authority in LTC and, instead, promoting the competence and, indeed, helpfulness of residents (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, #8). Although these were practical ideas generated by the RGs to address dining room experiences, neither RG viewed this topic as a project to pursue further. It is important to note that although these outcomes may or may not have produced direct community change, the process of PAR through the RGs illustrates the competence of LTC residents to contribute directly and proactively to ongoing culture change within their communities and to generate meaningful interaction and nurture relationships among themselves in the process.

Strengthening Relationships Among Residents, Staff, and Family: Community Teamwork and “General Policy”

In another nursing home RG, participants identified what they regarded as a lack of teamwork in their community and noted that this is problematic for residents’ experiences as well as the experiences of care staff. They claimed that improving teamwork could improve the QOL of residents and staff alike. Based on this concern, the group brainstormed together about what teamwork means and how to promote and enhance it in their community. These concerns and their resultant RG activities relate to culture change goals of de-emphasizing top-down bureaucratic authority within LTC communities and recognizing that culture change is an ongoing process rather than a formalized, pre-set program (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, #8 and #10). Over several weeks, the group identified and discussed four aspects of teamwork that they thought were important to strengthen in their community: respect, good attitude, having regular staff on shift, and good support from management. This discussion of teamwork generated two spin-off projects, each with the goal of initiating community dialogue about teamwork with the hope of improving everyone's experiences.

The first project was drafting a “General Policy” for all community members in their unit and sharing it with their community for feedback. The General Policy draft (see Figure 1) was aimed at both staff and residents and presented the groups’ ideas of what they considered principles and practices that should be followed by those living and working in their community. The group drafted a letter explaining their efforts and asking for input and distributed it with the General Policy to all nursing staff and residents in their unit and mailed it to all residents’ next of kin. They made an anonymous drop box for reactions, critiques, and suggestions about this draft policy. The General Policy included promoting a good attitude, giving compliments and praise, and taking time to share “little extras” with each other including good conversations.

Figure 1.

General policies.

Low staff participation and little community feedback overall in this RG extended the group's concern about staff experiences, so the group developed a second, related project to learn more about whether and how their unit's staff experience teamwork and to show their interest in staff experiences. They created four brief lists of questions for direct care staff, each focused on one of the four themes of respect, attitudes, support of co-workers, and management. Examples of questions included: how respected do you feel by residents? How supported by management do you feel when on the unit? Generally, what is the attitude of management toward nursing staff? They distributed these four lists of questions one at a time, anonymously, to all 50 direct care staff's mailboxes on their unit, hoping to encourage more staff participation in their efforts and to garner additional comments or specific experiences related to teamwork in their community. Between 7 and 10 staff participated in each questionnaire. Although the response rate was not impressive by standards of survey research, RG members were nevertheless very interested in their results. Some staff reported that they felt very respected and supported, whereas others indicated no sense of support from management, residents or other nurses, suggesting vast diversity of experiences of teamwork in this nursing home unit.

Based on the results of their projects, this RG continued dialogue about troubling aspects of the culture in their unit, specifically their sense that the morale of care staff was low. Although these projects did not result in immediate or discernible changes in teamwork on their unit, these processes of PAR were based on residents’ sophisticated ideas about teamwork and their concerns to improve their community. The development of these initiatives to understand the experiences of others, especially staff, is one example of the resident-led PAR process and its potential as a forum to transform relationships and reform communities.

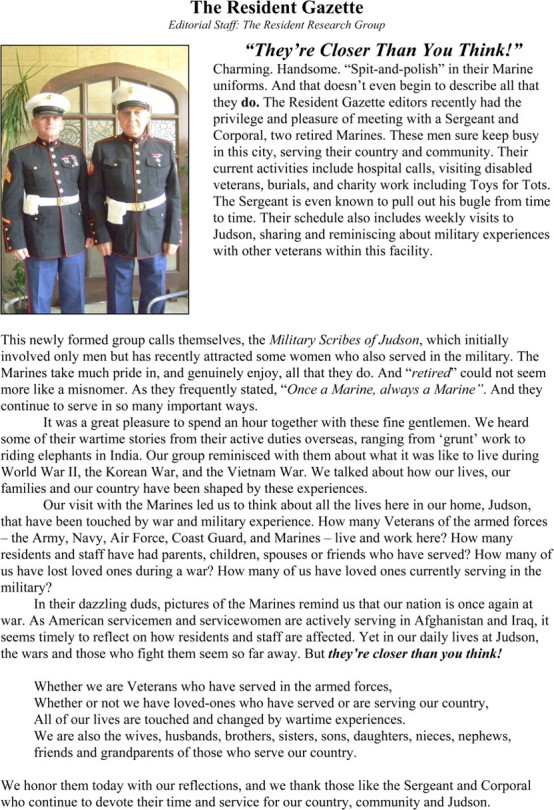

Providing Opportunities for Meaningful Social Engagement: Veteran Recognition Projects

In another RG, residents reminisced about work and hobbies, including journalism and photography, which they had not had the opportunity to pursue since entering the facility. They also noted concern that not all residents in their unit had equal ability and opportunity to participate in events held in other areas of the CCRC. In the course of this discussion, RG members decided to pursue a journalism project, reporting on events in their community from their unique perspectives to share information that may not be accessible to all of their neighbors, especially residents with considerable limitations. The group aimed to participate in a specific event together, discuss it and then write their own newsletter for their unit. This RG's concerns and resultant activities reflect the culture change principles of imbuing daily life with spontaneity in which unexpected events can take place and de-emphasizing the programmed activities approach to life in LTC (Pioneer Network, 2010; Thomas, 1996, p. 66, #5 and #6).

Armed with disposable cameras and audio recorders, the RG decided to focus their efforts on a small group of Marines who came to the facility each week to visit with other veterans. The group interviewed the Marines and listened to them share stories of their lives and military experiences. In subsequent meetings, the RG discussed what they considered highlights from this interview and connected these highlights to how each of their lives, their families, and the country have been shaped by war experiences, including contemporary armed conflicts. They outlined and drafted the first edition of their newsletter and named it the “Resident Gazette” (see Figure 2). The final version was distributed to all the residents and staff in their unit.

Figure 2.

Resident Gazette.

The interview with the Marines and resultant Resident Gazette generated yet other activities, in the form of two spin-off projects. First, the group discussed different symbols during wartime over the years, including the symbolism of the blue and gold stars that were hung in homes to signify having a loved one who is actively serving in the armed forces or who has died in service, respectively. This discussion led one resident to ask, “What do we have now? Why don’t we have something like that here?” The RG discussed how the blue and gold star concept could be implemented throughout the facility as a way to generate community solidarity, social support, and perhaps, they believed, healing among those residents and staff who had family who had served or were serving in the armed forces. Although the four months of formally planned RG meetings had concluded by this time, group members relayed their idea to department leaders in the social work and activities departments. As a result, at least two resident members participated, along with the visiting Marines, in planning and implementing the facility's Veteran's Day celebration. A table at this event was set up for all residents, family, and staff to honor a soldier or veteran they knew by writing their name on a blue or gold star. The stars were displayed on a “remembrance tree” in a public area decorated with other Veteran memorabilia, with the intention that the stars would eventually be returned to those residents so they may display it in their room.

Discussion

These RG projects offer examples of collective ideas for reform and community improvement within LTC that emerged through PAR, with small groups of residents acting as leaders in the identification of areas in need of improvement and the development of positive initiatives for community engagement and change. This project addressed a centrally important yet neglected aspect of culture change movements’ concern with the quality of residents’ experience within LTC by providing opportunities for them to exercise competence, thereby addressing directly the experience of helplessness. These results demonstrate that PAR is a viable method to engage residents and mobilize their expertise to stimulate creative reform ideas and initiatives within nursing home and assisted living settings, including memory support units. Our results suggest that PAR may be incorporated productively within various culture change efforts to engage residents as leaders and visionaries in reform processes.

This project also suggests that PAR has indirect positive benefits for residents’ QOL because it can provide fora for rich and meaningful social engagement, in contrast to institutionalized roles and routines that constrain them as predominantly passive and incompetent recipients of medical care. This is evidenced by remarks by some residents who praised this forum as distinct from and with more impact than participation in Resident Council meetings. One resident emphatically stated that PAR is “Better than Bingo!” and some residents negotiated with staff to prevent other appointments (physical therapy, baths, haircuts) from interfering with their RG participation.

When asked how the RG differs or compares to other activities in her community, one resident responded, “This is more formal … in other activities, like when someone is reading from the newspaper, staff and family don’t attend and none of us participate … same with sing-a-longs, bingo, arts and crafts.” This response highlights what this resident experienced as a qualitative difference in participation in an RG compared with many other LTC activities. Finally, after one RG meeting on a nursing home unit, one resident participant with cognitive challenges spontaneously expressed the positive value of participation in the RG in this way: “It's difficult sometimes for me. They say it's confusion, they say it may be early Alzheimer’s. I don’t know what I can do for you, but I want to keep busy. It's so nice to be involved in this. I don’t always keep up, but I hope you will continue to invite me.” Although these comments do not comprise a systematic evaluation of participants’ experiences in RGs, they suggest the distinct value of PAR RGs in a LTC setting for residents’ quality of lived experience as well as how RGs are experienced as distinct from preexisting social forums and activities.

By definition, PAR respects elders’ experience, wisdom, and insights. Our experience with RGs demonstrates their potential to reengage residents who have little opportunity to experience or demonstrate competence, to create more substantively significant and meaningful modes of connectedness, and to transform routinized, often ageist modes of relationships between residents, staff, and administrators. This potential is directly related to transformation of power differences within LTC structures, as PAR offers elders potentially respected and valued roles within LTC institutions, which may address helplessness and its kindred spirit, powerlessness. The lack of attention within culture change efforts to the role that residents can play in reform agendas must be understood as related to the cultural ageism that is a pervasive feature of society and several structural mechanisms that reinforce age segregation, including residential LTC settings (Dannefer & Shura, 2009). Age-based discrimination and social segregation render elders socially peripheral in terms of their place, meaning, and value in society. LTC settings are extreme examples of social segregation that is related to age. Often, prevailing beliefs about old age, old people, aging, and human development more generally—in lay public as well as among researchers and clinicians—underestimate or suppress recognition of elders’ capacities for generative community engagement, and more generally for growth, contribution, and learning in later life. When residents work together with staff and family members as teams with common interests of community improvement, the resulting social process has valuable potential for LTC reform.

This study took place within nursing home and assisted living areas within one CCRC. Although the results are promising, further research using PAR in LTC is needed to test whether these positive results would be replicated in other settings, and to examine how participation in PAR may be related to measures of lived experience within LTC, including but not limited to measures of residents’ life satisfaction, QOL, and health; staff job satisfaction and retention; and measures of social activity and community participation. The PAR model illustrated in this project requires further testing within myriad reform movements and diverse LTC settings.

In addition to its promise, our experiences with PAR in LTC suggest some challenges and limitations that warrant serious consideration but should not impede use of PAR in additional studies. These include facility support, staff participation, and sustainability. These three challenges suggest that empowerment via PAR may be qualified in specific ways within total institution settings. First, the support and strong rapport of administrators is necessary to use PAR effectively in LTC. Consistent investments in relationships between the PAR facilitators and administrators and other staff go a long way to smooth any unfamiliarity between staff and the PAR process, to inhibit related reluctance to participate in PAR, and to prevent scheduling conflicts regarding RGs’ meetings.

Second, staff participation in this study was low and irregular. Despite having many staff initially volunteer to participate, and despite efforts to schedule group meetings in ways that took into account staff availability, few staff participated regularly. It is interesting that higher rates of staff participation—both in numbers and regularity—were experienced in the two memory support unit RGs (in one case, all care staff working the same shift as the meeting wanted to participate and thus arranged a rotating schedule to maintain staff coverage on the unit). Work demands and time constraints were informally cited as contributing factors for low staff participation; in some units, residents speculated that staff seemed suspicious of the PAR process. In future PAR projects, strategies and incentives to motivate staff to be regular participants with the residents ought to be developed in order to improve the collective PAR processes.

Finally, as in other meaningful efforts at organizational change, sustainability is a significant issue and challenge, in part due to the resource-intensive nature of PAR. As researchers withdrew from their active presence as PAR facilitators after the four months of planned fieldwork, residents and other participants expressed a desire to continue the RGs. We sought ways to integrate the RGs into each unit so that they could be sustained after we were gone by discussing possibilities for sustainability with residents, social work and activities departments, unit managers, and other administrators. One administrator-in-training agreed to continue to facilitate one RG after our fieldwork ended. Despite these efforts, in most cases, the RGs waned and expired shortly after facilitators withdrew. Advances can be made in developing strategies to sustain PAR as a collective, community building process within LTC communities, and in gaining commitments to develop structural solutions from within the community. For example, if departments or Resident Councils within LTC communities were to accept responsibility for organizing and facilitating RGs, this would provide RG's with significantly higher levels of institutional support. Yet such support would have to be balanced with the potential that RGs have demonstrated to operate with a sense of independence from the overall organizational regime.

Conclusions

In rapidly aging societies, elders are a growing and undervalued natural resource (Experience Corps, 2010). William Thomas defines eldertopia as follows:

Eldertopia (noun) A community that improves the quality of life for people of all ages by strengthening and improving the means by which (1) the community protects, sustains, and nurtures its elders, and (2) the elders contribute to the well-being and foresight of the community. An Eldertopia that is blessed with a large number of older people is acknowledged to be “elder-rich” and uses this human capital to the advantage of all. (Thomas, 2004, p. 302)

LTC facilities, however characterized, comprise potential eldertopias with rich, untapped resources within their populations of elders. The culture change movement in LTC has prompted great improvements in some nursing homes and has made strides to address the plagues of boredom and loneliness (Thomas, 1996) and the corresponding human needs of autonomy and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2008). However, culture change has failed to address adequately the plague of helplessness, which reflects the lack of opportunities for residents to experience competence. It is no small task to restructure and otherwise reform institutionalized care settings in ways that offer elders improved nurturance and protection while simultaneously fostering their capacities to contribute to and be visionaries within their communities.

Our study suggests that PAR is a viable method of engaging elders as competent and agentic individuals—indeed, as experts who can generate and contribute positive collective ideas and initiatives for facility improvement. At the same time, such engagement contributes to the universal psychological need to experience competence (Deci & Ryan, 2008), and thereby addresses the nursing home plague of helplessness, which has remained rampant even under most conditions of culture change.

When elders are integrated into reform movements within LTC settings, age integration is achieved to a larger degree that in LTC communities that do not promote elders’ competence. Literature suggests that all people of all ages benefit from age integration, particularly marginalized older people (Hagestad & Uhlehberg, 2006; Riley & Riley, 1994). PAR is a method uniquely suited for enhanced culture change in LTC, primarily because it positions elders as competent leaders and visionaries in identifying key aspects of the community in need of improvement and developing creative reforms to address these challenges and to improve community life. PAR, as used in this study, also serves as a vehicle for increased age integration for LTC residents, as it fosters opportunities for cross-age connection inside and outside of LTC communities.

In sum, the results of this project suggest methods that can be used to engage and nurture the competence of residents in ways that can benefit them as individuals, the communities in which they live, and the processes of culture change within LTC. The culture change movement emerged to improve the culture and practices in institutions that provide support to elders who need it. One major premise of culture change is that “all elders are entitled to self-determination wherever they live” (Pioneer Network, 2010). This premise is deceptively radical, for it implicitly requires a shift in the definition of the role of the resident, and a shift in the balance of power between the resident role and the roles of others. It not only seeks to afford elders more choice in their lives and opportunities to express how they want to live but also expects from them more agentic and engaged participation in the daily construction of the reality of everyday life in the settings in which they live.

PAR is a method uniquely suited to enhance culture change in LTC by fostering such a shift in the balance of power through the RGs, primarily because it positions elders as competent leaders and visionaries in identifying key aspects of the community in need of improvement and in developing creative ideas for reforms. Thus, PAR provides the dual benefit of exploring ways to promote culture change at the organizational level while nurturing and affirming elders’ competence.

Funding

Reinberger Foundation.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the research participants and the leadership of Judson at University Circle, Cleveland, Ohio, where this research was conducted, for their investments in this project; Paul Stein for his support and mentorship as the consultant for use of the PAR method in LTC; Carolyn Lechner, Judith Harris, and Antje Daub for research assistance; and Paul Stein and Peter Uhlenberg for helpful comments on prior drafts of the manuscript.

References

- Anderson KL. Roles and job descriptions of nursing staff in a nursing home adhering to a resident-directed care philosophy. 2008 Policy/position paper by the Director of Clinical Services, Providence Mount St. Vincent, published online through Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. Retrieved January 6, 2010, from http://hartfordign.org/policy/position_papers_briefs. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, Wang CC. Photovoice: Use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience of older adults. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:1405–1413. doi: 10.1177/1049732306294118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan B. Live oak regenerative community: Championing a culture of hope and meaning. Journal of Social Work in Long-term Care. 2003;2:197–221. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick AL, Rader J, Hoeffer B, Sloane PD, Biddle S. Bathing without a battle: Person-directed care of individuals with dementia. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company, LLC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blair T, Minkler M. Participatory action research with older adults: Key principles in practice. Gerontologist. 2009;49:651–662. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CK. Providence Mount St. Vincent experience. Journal of Social Work in Long-term Care. 2003;2:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Butler R. Why survive? Being old in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins; 2002/1975. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins M, Kator MJ, Wyatt A, Halliday L. Culture change in action: Changing the experiential environment. Long-term Living. 2009;58(11):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MP, Marsden JP. Home is where the heart is: Designing to recreate home. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly. 2000;1(1):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MP, Marsden JB, Briller SH. Creating successful dementia care settings. New York: Health Sciences; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Casper S, O’Rourke N, Gutman GM. The differential influence of culture change models on long-term care staff empowerment and provision of individualized care. Canadian Journal of Aging. 2009;28:165–175. doi: 10.1017/S0714980809090138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth L, Kilstoff K. Organizational and structural reform in aged care organizations: Empowerment towards a change process. Journal of Nursing Management. 2002;10:235–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2002.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler LJ, Kane RA. Post-occupancy evaluation of the transformed nursing home: The first four Green House ® Settings. Journal of Housing for the Elderly. 2009;23:304–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Shura PR. The missing person: Some limitations in the contemporary study of cognitive aging. In: Alwin D, Hofer S, editors. International handbook of cognitive aging. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Shura PR. Experience, social structure and later life: Meaning and old age in an aging society. In: Uhlenberg P, editor. International handbook of population aging. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. pp. 747–755. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Stein P. From the top to the bottom, from the bottom to the top: Systemically changing the culture of nursing homes. 2000 Unpublished Final Report, Van Amerigen Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Stein P, Siders R, Shura R. Is that all there is? The concept of care and the dialectic of critique. Journal of Aging Studies. 2008;22:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology. 2008;49:182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond T. Social policy and everyday life in nursing homes: A critical ethnography. Social Science and Medicine. 1986;23:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond T. Making gray gold: Narratives of nursing home care. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M, Timonen V. Lessons from a community-based participatory research project: Older people's and researchers’ reflections. Research on Aging. 2010;32:244–263. [Google Scholar]

- Eden Alternative. Our 10 Principles. 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2010, from www.edenalt.org. [Google Scholar]

- Experience Corps. Experience after school: Engaging older adults in after-school programs. 2010. Retrieved January 07, 2010, from www.experiencecorps.org/news/afterschoolreport/intro.html. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan RM. Pioneer network: Changing the culture of aging in America. Journal of Social Work in Long-term Care. 2003;2(1–2):125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan RM, Williams CC, Burger SG. Meeting of pioneers in nursing home culture change. Rochester, NY: Lifespan of Greater Rochester; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Foner N. The caregiving dilemma: Work in an American nursing home. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Anchor; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J. Living and dying at Murray Manor. New York: St. Martins; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hagestad GO, Uhlehberg P. Should we be concerned about age segregation? Some theoretical and empirical explorations. Research on Aging. 2006;28:638–653. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen JJ, III, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 46–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SP, Auton MF, Burton CR, Watkins CL. Engaging service users in the development of stroke services: An action research study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17:1270–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg A, Reskin BF, Hudson K. Bad jobs in America: Standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA, Lum TY, Cutler LJ, Degenholtz HB, Yu T. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: A longitudinal evaluation of the initial Green House program. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones JS. Old, alone, and neglected: Care of the aged in the United States and Scotland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones JS, Beard RL, Sharpp TJ. Dying with a stage IV pressure ulcer: An analysis of a nursing home's gross failure to provide competent care. American Journal of Nursing. 2009;109:40–48. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000344036.26898.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: The culture-change movement. Health Affairs. 2010;29:1–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pioneer Network. Values, Vision, Mission. 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2010, from www.pioneernetwork.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rabig J. Home again: Small houses for individuals with cognitive impairment. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2009;35:10–15. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20090706-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabig J, Thomas W, Kane RA, Cutler LJ, McAlilly S. Radical redesign of nursing homes: Applying the green house concept to Tupelo, Mississippi. Gerontologist. 2006;46:533–539. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman AN, Schnelle JF. The nursing home culture-change movement: Recent past, present, and future directions for research. Gerontologist. 2008;48:142–148. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray M. Redressing the balance? The participation of older people in research. In: Bernard M, Scharf T, editors. Critical perspectives on aging societies. Bristol, UK: Polity Press; 2007. pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Riley MW, Riley JW., Jr Age integration and the lives of older people. Gerontologist. 1994;3–4:110–115. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WH. Life worth living: How someone you love can still enjoy life in a nursing home. Acton, MA: Vanderwyk & Burnham; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WH. What are old people for? How elders will save the world. Acton, MA: VanderWyk & Burnham; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WH, Blanchard JM. Moving beyond place: Aging in community. Generations. 2009;33:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WH, Johansson C. Elderhood in Eden. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2003;19:282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck B. Unloving care: The nursing home tragedy. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth Y. What is participatory action research? 1998 Action Research International, Paper 2. Retrieved October 10, 2006, from http://www.scu.edu.au/p-ywadsworth98.html. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner D, Hanlon JT. Pain in nursing home residents: Management strategies. Drugs and Aging. 2001;18:13–29. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner AS, Ronch JL. Culture change in long-term care. New York: Haworth Social Work Practice Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- White DL, Newton-Curtis L, Lyons KS. Development and initial testing of a measure of person -directed care. Gerontologist. 2008;48:114–123. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Chu EF, Graves WJ, Godfrey SM, Bonner A, Sloane P. Beyond the medical model: The culture change revolution in long-term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WF. Advancing scientific knowledge through participatory action research. Sociological Forum. 1989;4:367–385. [Google Scholar]