Abstract

Sheng, Lavonne, Weilin Zhou, Alison A. Hislop, Basil O. Ibe, Lawrence D. Longo, and J. Usha Raj. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in ovine fetal pulmonary vascular remodeling following exposure to high altitude long-term hypoxia. High Alt. Med. Biol. 10:365–372, 2009.—High altitude long-term hypoxia (LTH) in the fetus may result in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell (PVSMC) proliferation and pulmonary vascular remodeling. Our objective was to determine if epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is involved in hypoxia-induced PVSMC proliferation or in pulmonary vascular remodeling in ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude LTH. Fetuses of pregnant ewes that were held at 3820-m altitude from ∼30 to 140 days (LTH) gestation and sea-level control pregnant ewes were delivered near term. Morphometric analyses and immunohistochemistry were done on fetal lung sections. Pulmonary arteries of LTH fetuses exhibited medial wall thickening and distal muscularization. Western blot analyses done on protein isolated from pulmonary arteries demonstrated an upregulation of EGFR. This upregulation was attributed in part to PVSMC in the medial wall by immunohistochemistry. Proliferation of fetal ovine PVSMC after 24 h of hypoxia (2% O2) was attenuated by inhibition of EGFR with 250 nmol tyrphostin 4-(3-chloroanilino)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline (AG1478), a specific EGFR protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, when measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Our data indicate that EGFR plays a role in fetal ovine pulmonary vascular remodeling following long-term fetal hypoxia and that inhibition of EGFR signaling may ameliorate hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Key Words: EGFR, fetal pulmonary vasculature, smooth muscle, proliferation

Introduction

In utero, the fetus is exposed to an environment of relatively low oxygen tension, which stimulates pulmonary vasoconstriction. This low oxygen tension, along with other modulators of vasoconstriction such as thromboxane A2 (Tod and Cassin, 1985) and endothelin-1 (Ivy et al., 1996), contribute to the maintenance of a high pulmonary vascular resistance (Raj and Shimoda, 2002). At birth, breathing results in increased oxygen tension, lung expansion, and pulmonary vasorelaxation. Along with increased systemic vascular resistance, these stimuli work collectively to allow for effective pulmonary blood flow and gas exchange. Any disruption in the delicate environment can result in a failure of this critical transition, with persistent pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary vascular remodeling, leading to the clinical entity of pulmonary hypertension with systemic hypoxemia.

Although there are various etiologies for persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) with a wide spectrum of clinical severity, there has been consistent evidence of pulmonary vascular remodeling seen in both human infants and animal models of PPHN. Smooth-muscle cell proliferation and extension into normally nonmuscular distal pulmonary arteries are characteristic changes described in PPHN (Murphy et al., 1981).

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and other EGF receptor (EGFR) ligands are potent mitogens and have been shown to trigger proliferation in various cell lines, including vascular smooth-muscle cells (Jin et al., 2002; Roztocil et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2007). Although the roles of EGF and EGFR in lung carcinoma (Singh and Harris, 2005) and in response to vascular injury (Zhang et al., 2004) have been studied, their specific roles in pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension induced by chronic hypoxia have not yet been elucidated.

In this study, we first establish that in ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude long-term hypoxia there is pulmonary vascular remodeling, similar to that of PPHN. Given the previously established role of EGFR in vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation, we hypothesized that EGFR plays a role in pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation and pulmonary vascular remodeling following chronic hypoxia. EGFR expression was determined in lung tissue sections from chronically hypoxic and normoxic control fetal lambs, and the functional role of EGFR in pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation in hypoxia was studied.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibody to smooth-muscle specific α-actin isoform was purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK). Biotin-conjugated sheep antimouse and streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (HRP) complex were purchased from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). Polyclonal rabbit antibody against EGFR and monoclonal mouse antibody against proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were both from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Tryphostin 4-(3-chloroanilino)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline (AG1478) was purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA).

Animals

As previously described, (Longo and Pearce, 2005; Gao et al., 2006; Bixby et al., 2007), fetal lungs were used for preparation of fixed lung tissue sections for morphometry, dissection of pulmonary blood vessels for protein isolation, and culture of pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cells (PVSMC). For the high altitude the long-term hypoxia group, pregnant ewes were kept at Barcroft Laboratory, White Mountain Research Station, Bishop, CA, USA (altitude 3820 m; Pao2 60 ± 2 mmHg) from approximately 30 days gestation to near term (term being 147 days). The ewes were brought down to sea level just before delivery. They were then sacrificed, the fetuses were removed, and their lungs were harvested for study. For the control group, pregnant ewes were kept at sea level for their entire gestation and were sacrificed at a gestational age comparable to the high altitude LTH group. As reported by Kamitomo and colleagues (1993), in this animal model no differences were noted in body or organ weights between sea-level controls and high altitude LTH fetuses; but fetal Pao2 was decreased from 25 to 19 mmHg, and fetal hemoglobin was increased from 10.1 ± 0.7 to 12.6 ± 0.6g/dL. All animals for these studies were obtained during the fall and winter of late 2005 to early 2006. The studies were approved by the IRB and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute, Torrance, California, and the IRB and the Animal Care and Use Committee of Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California.

Cell culture

As in previously reported studies (Zhou et al., 2007), pulmonary vascular PVSMCs were cultured from near-term ovine fetal pulmonary arteries, fourth through sixth generation, and prepared. Briefly, adventitia was removed by forceps dissection and by collagenase I digestion. PVSMCs were isolated by incubation with collagenase II and followed by filtration to removed tissue debris. Morphology of the freshly prepared SMC was confirmed by a hill-and-valley appearance and by α-smooth-muscle actin immunofluorescent staining. All cell culture studies were conducted at 37°C in incubators aerated with 5% CO2 in air. Culture media were Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 25 μg/mL amphotericin B. Cells were passaged every 4 to 7 days using 0.05% trypsin-0.53 mmol EDTA. All experiments were done at cell passage 4 to 6. We have previously reported that passaged cells continue to express α- smooth-muscle actin and myosin light-chain kinase proteins (Bixby et al., 2007; Ibe et al., 2008).

Tissue and slide preparation, immunohistochemistry for morphometric analyses, and morphometric measurement of pulmonary arteries and veins

Lungs were distended and fixed in formalin, and subsequently embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-μm sections. Similar to previously published protocols (Bixby et al., 2007), 4-μm paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with antibody to smooth-muscle specific α- \actin isoform (1:3000). Heat antigen retrieval was performed, and endogenous peroxidase activity and nonspecific antibody binding were blocked. Sections were incubated with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody was biotin-conjugated sheep antimouse. After incubation with streptavidin biotinylated HRP complex and 3, 3′-diaminobenzinine (DAB, Sigma, UK), sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Color images from α-actin stained slides of 4 hypoxic and 4 control animals of each gender were obtained with a digital camera (Zeiss Axiocam, Imaging Associates, Thame, UK). Analysis was made using Openlab v3.15 software (Improvision Ltd., Coventry, UK). Investigators were blinded as to whether samples were hypoxic or normoxic. Muscular arteries accompanying specific airways (small bronchioli, terminal bronchioli, respiratory bronchioli, and alveolar ducts) were studied in each group, using at least 10 vessels at each level for each animal. Twice the medial wall thickness was calculated and expressed as a percentage of external diameters. A mean value for each airway level in each group was calculated for percentage of medial wall thickness, since there was no statistical difference between animals in the same group. This method has been used and described in depth in previous publications (Hislop and Reid, 1972).

Western blot for expression of EGFR and proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)

Pulmonary arteries (fourth generation and beyond) of LTH ovine fetuses and sea-level controls (n = 4 for each group) were dissected, cleaned of parenchyma, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein was isolated from the frozen pulmonary arteries by mortar and pestle and homogenization with RIPA buffer containing 1 mmol PMSF (Sigma) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentration was determined with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Five-μg samples were subjected to Bis-Tris (NuPAGE Novex, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. Nonspecific binding of antibody was blocked by washing with TBST containing 5% milk and incubating overnight with primary antibody at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated for 2 h with secondary antibody. Antibody complexes were detected using the chemiluminescence method with SuperSignal West Pico substrate solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL,USA). Analysis by densitometry was done with Un-Scan-It software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT, USA). Values were normalized to actin blot density.

Immunohistochemistry for EGFR, PCNA, and α-smooth-muscle actin

Four-μm tissue sections were double-stained with antibodies to α-smooth-muscle actin (SMA) (1:1000 or 1:2000) and PCNA (1:1000) with the EnVision Doublestain System (Dako-Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Heat antigen retrieval was performed with sodium citrate buffer. Protocol 2 of the kit was used, which requires 30-min incubation time rather than 10 min with each of the following: primary antibody peroxidase-labeled polymer and alkaline phosphatase-labeled polymer. This protocol is designed to allow for increased sensitivity and staining intensity. Sections were then lightly counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were taken with Zeiss Axiocam (Imaging Associates, Oxfordshire, UK). Sections from both hypoxic fetuses and sea-level controls were examined with n = 3 for each group.

Cell proliferation quantitation by [3H]-thymidine incorporation

Fetal ovine PVSMC were grown to subconfluence and starved overnight in DMEM with 0.5% FBS. Cells were then treated with 250 nmol AG1478 (Biomol), a specific EGFR inhibitor or vehicle, and exposed to a hypoxia gas mixture containing 2% O2, 10% CO2, and balance nitrogen, as in previous work from our lab (Ibe et al., 2002; Ibe et al., 2008), for 24 h. Immediately prior to exposure to hypoxia, the cells were labeled with 0.5 μCi/mL of [3H]-thymidine (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA). After 24 h of hypoxia, the cells were then harvested and the quantity of [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured by scintillation spectrometer (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Three experiments were done. Values are expressed as a percent of control.

Statistical Analysis

All numerical data, morphometric analyses, and cell proliferation studies are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-tailed the Student t test. For multiple comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni's post hoc-test was done with JMPIN software version 4.0 (SAS Institute, Cary NC, USA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

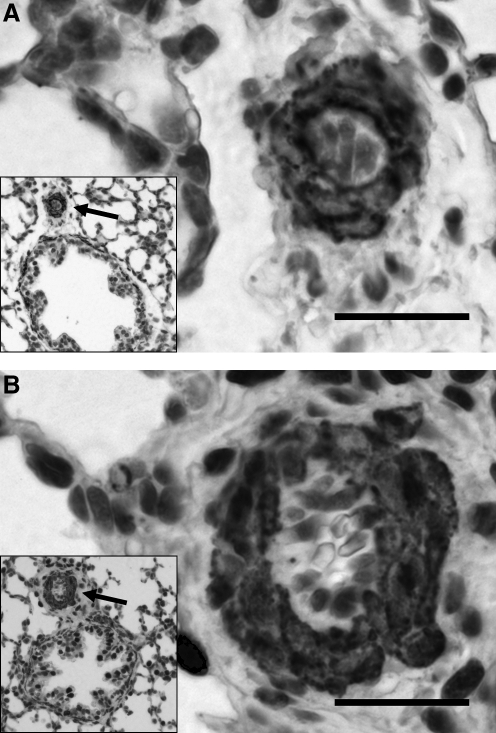

Increased muscularization of pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude long-term hypoxia

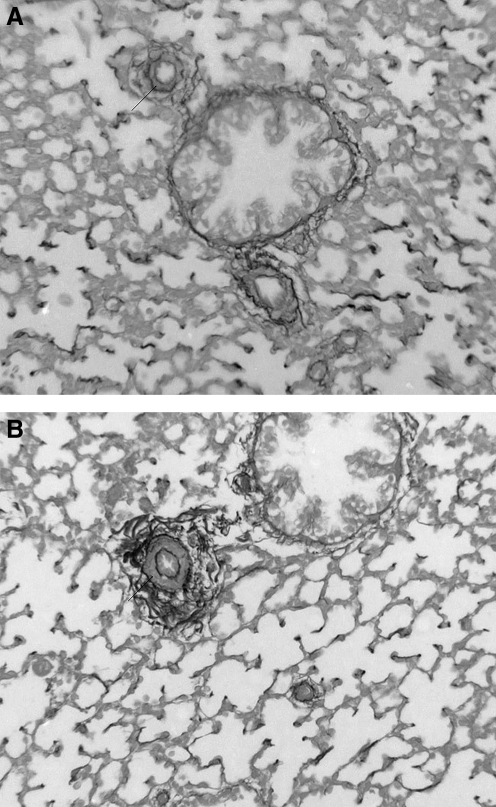

As reported in previous work by our group (Bixby et al., 2007), compared to sea-level controls, pulmonary arteries of fetal sheep exposed to high altitude LTH did not have significantly different overall external diameters; yet they demonstrated increased muscularization at all levels, contributing to an increase in the percent of wall thickness. Further analysis by gender revealed no significant differences (data not shown). With both genders, the enhanced muscularization was most pronounced at the level of the alveolar ducts, that is, the more distal segments of the pulmonary arteries. The increased muscularization of the pulmonary arteries after exposure to high altitude LTH can be appreciated in representative images with elastin staining (Fig. 1). Additional analysis showed no significant remodeling in the pulmonary veins (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Ovine fetal pulmonary arteries and their accompanying airways. Representative photomicrographs of pulmonary arteries from sea-level controls (A) and ovine fetuses in high altitude long-term hypoxia (B). Four-μm tissue sections stained for elastin. There is increased muscularity in the hypoxic vessel.

Increased expression of EGFR in the medial walls of pulmonary arteries of chronically hypoxic ovine fetuses

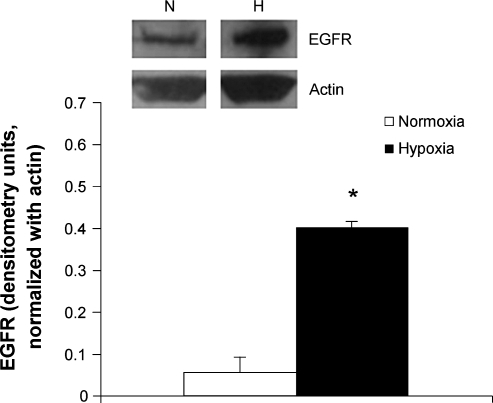

By Western blot analysis, protein isolates from the pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude LTH showed a significant increase in the expression of EGFR when compared with those of sea-level controls (Fig. 2). By immunohistochemistry staining for the receptor, this increase in EGFR could be partly localized to the medial wall of the pulmonary arteries (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

EGFR protein in pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses. Western blot analysis was done of protein isolates from pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude long-term hypoxia and sea-level controls, n = 3. Top panel is representative blots, bottom panel is densitometry, expressed in arbitrary units and normalized with actin. *p < 0.01.

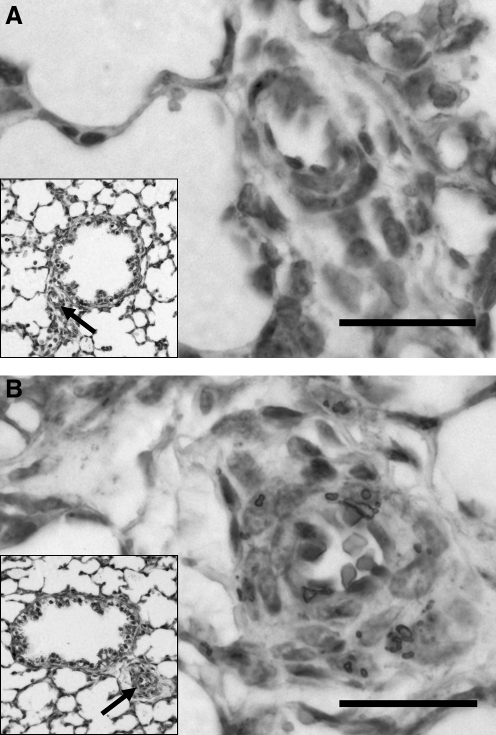

FIG. 3.

EGFR expression in fetal ovine pulmonary arteries. Compared with sea-level control (A), there is upregulation of EGFR in the pulmonary artery exposed to high altitude longterm hypoxia (B) at 400 ×. Bar = 20 μm. Immunohistochemistry of 4-mm sections stained with EGFR antibody and then counterstained with hematoxylin.

Increased smooth-muscle cell proliferation in medial wall of pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to chronic hypoxia

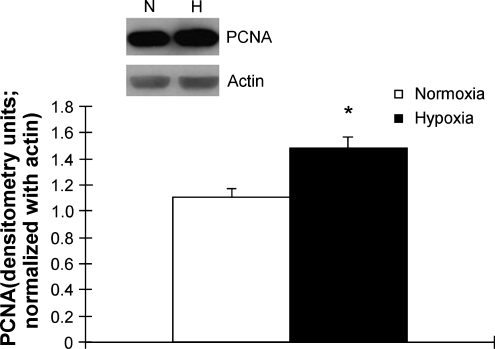

Protein isolates from these vessels were probed with a monoclonal antibody for PCNA and normalized with actin. Levels of PCNA were elevated by approximately 25% in hypoxic ovine fetal pulmonary arteries when compared with sea-level controls (Fig. 4). By co-localization with α-smooth-muscle actin, part of the increase in PCNA could be pinpointed to the smooth muscle cells in the medial wall of the pulmonary arteries from hypoxic ovine fetuses by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 5). There was increased staining of the smooth-muscle cell nuclei in the hypoxic pulmonary arteries, within the thickened medial wall layer. This was consistent with the findings of the morphometric analyses.

FIG. 4.

Proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in ovine fetal pulmonary arteries. Western blot analysis of PCNA, a nuclear marker of cell proliferation, in protein isolates from pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude long-term hypoxia and sea-level controls, *p = 30.05. Top panel is representative blots and bottom panel is densitometry, expressed in arbitrary units, and normalized with actin.

FIG. 5.

Proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and α-smooth muscle actin in fetal ovine pulmonary arteries. PCNA (brown) and alpha-smooth-muscle actin (red) by immunohistochemistry using DakoCytomation Envision Doublestain Kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) at 400× in ovine fetuses from sea-level control (A) and high altitude long-term hypoxia (B). Bar = 20 μm.

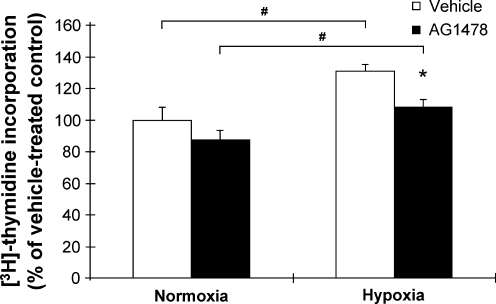

Hypoxia-induced PVSMC proliferation blunted by EGFR inhibition

Ovine fetal PVSMC were treated with AG1478, an EGFR specific inhibitor, and then cultured in hypoxia (2% O2). AG1478 is a competitive inhibitor of the ATP binding site in the kinase domain of the EGFR tyrosine kinase. In normoxia, 250 nmol AG1478 did not have a significant effect on baseline PVSMC proliferation. When the PVSMC were exposed to hypoxia, the inhibition of EGFR by AG1478 ameliorated hypoxia-induced cell proliferation as measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation (Fig. 6). This supported our hypothesis that EGFR activation is important for PVSMC proliferation, and hypoxia-induced cell proliferation may be due in part to activation of EGFR.

FIG. 6.

Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell (PVSMC) proliferation and the effect of a specific EGFR inhibitor (AG1478). PVSMC exposed to 2% O2 for 24 h. Cell proliferation measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation and expressed as percent of vehicle-treated control in normoxia. #,*p < 0.05 for hypoxia-induced proliferation in both vehicle and AG1478 treatment groups, as well as for diminished hypoxia-induced cell proliferation in the AG1478 treatment group compared with the vehicle group. The difference in proliferation between the two normoxia groups was not significant.

Discussion

In this study, as well as in previously published data from our laboratory (Bixby et al., 2007), we provide further evidence of pulmonary vascular remodeling following exposure to high altitude LTH in both male and female fetal lambs. There was a minimal increase in the external diameter of pulmonary arteries at the level of the proximal small bronchioles, but there was significant muscularization throughout the vascular tree that was examined. This was most notable distally, at the level of the alveolar ducts. Similar remodeling has been seen in human neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), as well as in animal models of the same pathologic condition (Haworth and Reid, 1976; Stenmark et al., 1987; Wild et al., 1989; Belik et al., 1994), suggesting that this particular ovine model is suitable for further study of the etiology and pathology of PPHN. Previously, various models of PPHN have been created with both acute and chronic hypoxia. Attempts to simulate PPHN after acute hypoxia include hypoxic vasoconstriction of the growing pig and meconium aspiration in newborn baboons after intermittent umbilical cord compression (Rendas et al., 1982; Cornish et al., 1994). There have also been models with a longer duration of umbilical cord compression, for up to 14 days (Soifer et al., 1987). Another animal model of chronic hypoxia involved exposing newborn calves to high altitude hypoxia (Stenmark et al., 1987).

In utero hypoxia secondary to maternal hypoxia has also been shown to result in pulmonary hypertension. Thirty minutes of breathing 10% to12% O2 by pregnant ewes can result in a significant reduction in fetal Pao2 along with increases in pulmonary artery pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance (Abman et al., 1987). A longer duration of hypoxia has been attempted with pregnant rats, resulting in morphometric changes in the pulmonary vasculature of the newborn rats (Goldberg et al., 1971). Our group is the first to document similar morphometric changes in an in utero high altitude LTH sheep model. Future investigation to further validate this in utero high altitude LTH sheep model of persistent pulmonary hypertension will require physiologic evaluations, such as measurements of right ventricular pressure or right ventricular hypertrophy (change in right to left ventricular + septal weight; RV/[LV+S]).

Neonatal and adult sheep have been shown previously to be hyporesponders to high altitude hypoxia in terms of developing pulmonary hypertension (Tucker and Rhodes, 2001). This lack of response is thought to be because of a paucity of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle in the species. Our studies indicate that, unlike their newborn and adult counterparts, fetal sheep are sensitive to in utero high altitude LTH, with morphometric analyses showing pulmonary vascular remodeling. These findings differ from those of a recent study conducted independently on the same animal model (Xue et al., 2008). Although both studies examined the same number of animals with n = 4 and came to similar conclusions regarding the lack of vascular remodeling in the pulmonary veins, the study by Xue et al. did not find any difference in pulmonary artery medial wall thickness between LTH and sea-level control groups. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in methods, as our analysis was done at multiple levels of pulmonary arteries, after examination of 10 different vessels at each level for each animal. This allowed us to not only demonstrate increased medial wall thickness, but distal muscularization as well. In addition, our data are presented as a percentage of the overall wall thickness made up by the medial wall layer, rather than by a straight measurement of the medial wall thickness, accounting for potential variation in the overall external diameter of each vessel.

Much has also been studied in terms of gender differences in response to chronic hypoxia, and for this reason our morphometric analysis was also done in a gender-specific manner, although we did not discover any gender difference in remodeling (data not shown). In an earlier report, Burton and colleagues (1968) noted some gender differences in the effect of hypoxia in chickens. They demonstrated that male chickens living in relative hypoxia at high altitude for 1 year had higher mean pulmonary arterial blood pressures and larger right ventricles than did female chickens. Similar gender disparity has been reported in pig and sheep models (McMurtry et al., 1973; Rabinovitch et al., 1981). Studies have suggested that this difference may be attributed to a less prominent pulmonary vasomotor response to hypoxia in females (Wetzel and Sylvester, 1983), perhaps related to the protective effects of estrogen (Rendas et al., 1982; Resta et al., 2001; Lahm et al., 2007). Younger animals seem to have increased pulmonary vascular sensitivity to hypoxia, with infants displaying higher pulmonary artery pressures, more significant RV hypertrophy, and fewer gender differences (Rabinovitch et al., 1981). Our findings also support this, showing that both male and female ovine fetuses display significant pulmonary vascular remodeling in response to chronic in utero hypoxia. Thus both male and female fetuses were used in our experiments and data were pooled.

Along with vascular remodeling in the lung, we also found increased EGFR expression in the pulmonary arteries of these hypoxic fetal sheep. EGFR, a 170 kD glycoprotein transmembrane receptor, is a member of the erbC family of receptor tyrosine kinases with various ligands, including EGF and TGF-α. It plays many important roles in cell functions, such as differentiation, motility, growth, proliferation, and survival (Singh and Harris, 2005). EGFR has been shown to specifically affect smoothmuscle cells. For example, EGFR induces growth and proliferation of bladder smoothmuscle cells exposed to hypoxia (Sabha et al., 2006). In vascular smooth-muscle cells, EGFR mediates catecholamine-induced growth and has been found to play a role in intimal thickening preceding atheromas in coronary arteries (Chan et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). EGF, one of the ligands of EGFR, stimulates the proliferation of human pulmonary artery smooth-muscle cells, and this proliferation can be enhanced by hypoxia (Schultz et al., 2006). EGFR has also been directly associated with pulmonary vascular remodeling during postnatal development, although studied in epithelial cells (Le Cras et al., 2004).

In this study, the increase in EGFR in pulmonary arteries of chronically hypoxic fetuses was in part localized to the medial layer of vascular smooth-muscle cells. In fact, along with the increase in EGFR, there was an associated increase in cell proliferation, as indicated by PCNA overexpression in the smooth-muscle cell layer of the pulmonary arteries of high altitude LTH ovine fetuses. PCNA is synthesized in early G1 and S phases of the cell cycle and is localized to the nucleus. It plays a role in cell-cycle progression, DNA replication, and DNA repair. This co-localization supports an association between EGFR upregulation and pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation. Thus activation of EGFR may play a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary vascular remodeling.

Previously published data from other groups have shown that EGFR is up-regulated by hypoxia in other pulmonary vascular cell types as well. Hypoxia-induced proliferation of pulmonary artery adventitial fibroblasts is in part owing to the transcription factor early growth response-1 (Egr-1), by upregulation of downstream EGFR (Banks et al., 2005). This increased expression of EGFR in other pulmonary vascular cell types can explain the relatively greater signal difference on the western blot analysis of whole, intact pulmonary artery (PA) when compared with the immunohistochemistry.

If EGFR has a role in pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation, inhibiting its function should dampen the proliferative effects of hypoxia. Previous work from our lab has demonstrated that platelet-activating factor (PAF), a phospholipid present in high circulating levels in the near-term fetal lamb (Ibe et al., 1998), induces fetal pulmonary vascular smooth-muscle cell proliferation in vitro (Ibe et al., 2008). PAF has been shown to induce pulmonary venous smooth-muscle cell proliferation by EGFR transactivation in vitro (Zhou et al., 2007). Also, as previously reported, PAF synthesis and PAF receptor protein expression are up-regulated in pulmonary arteries of ovine fetuses exposed to high altitude LTH (Bixby et al., 2007). In the present study, while there was attenuation of hypoxia-induced PVSMC proliferation by EGFR inhibition with AG1478, no significant change in the muscularization of the pulmonary veins was observed by morphometric analysis. This suggests that, in vivo, significant transactivation of EGFR by PAF may not be taking place to induce pulmonary venous remodeling.

In summary, results from this study demonstrate that in a sheep model of in utero high altitude LTH, pulmonary vascular remodeling similar to that seen in other animal models of pulmonary hypertension occurs. There is evidence of increased expression of EGFR, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor associated with the growth and proliferation of vascular smooth-muscle cells within the medial walls of these remodeled vessels. In addition, EGFR also plays a role in hypoxia-induced PVSMC proliferation when studied in vitro. Evidence for direct causation is still needed, along with elucidation of potential pathways and downstream mechanisms. However, the present report suggests that EGFR inhibition may modulate the pulmonary vascular remodeling found in PPHN.

Ackowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants NIH 5RO1 HL077819 and 5RO1 HL075187 to J. Usha Raj and PO1 HD 031226 to Lawrence D. Longo.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- Abman S.H. Accurso F.J. Wilkening R.B. Meschia G. Persistent fetal pulmonary hypoperfusion after acute hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253(4 Pt 2):H941–H948. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.4.H941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks M.F. Gerasimovskaya E.V. Tucker D.A. Frid M.G. Carpenter T.C. Stenmark K.R. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;98:732–738. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00821.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belik J. Keeley F.W. Baldwin F. Rabinovitch M. Pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in fetal sheep. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266(6 Pt 2):H2303–H2309. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixby C.E. Ibe B.O. Abdallah M.F. Zhou W. Hislop A.A. Longo L.D. Raj J.U. Role of platelet activating factor in pulmonary vascular remodeling associated with chronic high-altitude hypoxia in ovine fetal lambs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;293(6):L1475–L1482. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00089.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton R.R. Besch E.L. Smith A.H. Effect of chronic hypoxia on the pulmonary arterial blood pressure of the chicken. Am. J. Physiol. 1968;214(6):1438–1442. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1968.214.6.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.K. Kalmes A. Hawkins S. Daum G. Clowes A.W. Blockade of the epidermal growth factor receptor decreases intimal hyperplasia in balloon-injured rat carotid artery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003;37(3):644–649. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish J.D. Dreyer G.L. Snyder G.E. Kuehl T.J. Gerstmann D.R. Null D.M., Jr. Coalson J.J. deLemos R.A. Failure of acute perinatal asphyxia or meconium aspiration to produce persistent pulmonary hypertension in a neonatal baboon model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;171(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Portugal A.D. Negash S. Zhou W. Longo L.D. Raj J.U. Role of Rho kinases in PKG-mediated relaxation of pulmonary arteries of fetal lambs exposed to chronic high altitude hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006;292(3):L678–L684. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00178.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S.J. Levy R.A. Siassi B. Betten J. The effects of maternal hypoxia and hyperoxia upon the neonatal pulmonary vasculature. Pediatrics. 1971;48(4):528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth S.G. Reid L. Persistent fetal circulation: newly recognized structural features. J. Pediatr. 1976;88(4 Pt. 1):614–620. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop A. Reid L. Intra-pulmonary arterial development during fetal life-branching pattern and structure. J. Anat. 1972;113(1):35–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibe B.O. Abdallah M.F. Portugal A.M. Raj J.U. Platelet-activating factor stimulates ovine foetal pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation: role of nuclear factor-kappa B and cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell Proliferation. 2008;41(2):208–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibe B.O. Hibler S. Raj J.U. Platelet-activating factor modulates pulmonary vasomotor tone in the perinatal lamb. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;85(3):1079–1085. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibe B.O. Portugal A.M. Raj J.U. Metabolism of platelet activating factor by intrapulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells: effect of oxygen on phospholipase A2 protein expression and activities of acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase and cholinephosphotransferase. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2002;77(3):237–248. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy D.D. Kinsella J.P. Abman S.H. Endothelin blockade augments pulmonary vasodilation in the ovine fetus. J Appl. Physiol. 1996;81(6):2481–2487. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K. Mao X.O. Sun Y. Xie L. Jin L. Nishi E. Klagsbrun M. Greenberg D.A. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor: hypoxia-inducible expression in vitro and stimulation of neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2002;22(13):5365–5373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05365.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitomo M. Alonso J.G. Okai T. Longo L.D. Gilbert R.D. Effects of long-term, high-altitude hypoxemia on ovine fetal cardiac output and blood flow distribution. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993;169(3):701–707. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90646-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahm T. Patel K.M. Crisostomo P.R. Markel T.A. Wang M. Herring C. Meldrum D.R. Endogenous estrogen attenuates pulmonary artery vasoreactivity and acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the effects of sex and menstrual cycle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;293(3):E865–E871. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00201.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cras T.D. Hardie W.D. Deutsch G.H. Albertine K.H. Ikegami M. Whitsett J.A. Korfhagen T.R. Transient induction of TGF-alpha disrupts lung morphogenesis, causing pulmonary disease in adulthood. Am. J. Physiol Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2004;287(4):L718–L729. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00084.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo L.D. Pearce W.J. Fetal cerebrovascular acclimatization responses to high-altitude, long-term hypoxia: a model for prenatal programming of adult disease? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005;288(1):R16–R24. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00462.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry I.F. Frith C.H. Will D.H. Cardiopulmonary responses of male and female swine to simulated high altitude. J. Appl. Physiol. 1973;35(4):459–462. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J.D. Rabinovitch M. Goldstein J.D. Reid L.M. The structural basis of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn infant. J. Pediatr. 1981;98(6):962–967. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80605-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch M. Gamble W.J. Miettinen O.S. Reid L. Age and sex influence on pulmonary hypertension of chronic hypoxia and on recovery. Am. J. Physiol. 1981;240(1):H62–H72. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.1.H62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj U. Shimoda L. Oxygen-dependent signaling in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2002;283(4):L671–L677. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00177.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendas A. Branthwaite M. Lennox S. Reid L. Response of the pulmonary circulation to acute hypoxia in the growing pig. J. Appl. Physiol. 1982;52(4):811–814. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta T.C. Kanagy N.L. Walker B.R. Estradiol-induced attenuation of pulmonary hypertension is not associated with altered eNOS expression. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2001;280(1):L88–L97. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.1.L88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roztocil E. Nicholl S.M. Galaria I.I. Davies M.G. Plasmin-induced smooth muscle cell proliferation requires epidermal growth factor activation through an extracellular pathway. Surgery. 2005;138(2):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabha N. Aitken K. Lorenzo A.J. Szybowska M. Jairath A. Bagli D.J. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and epidermal growth factor receptor mediate hypoxia-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and subsequent proliferation in bladder smooth muscle cells. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2006;42(5-6):124–133. doi: 10.1290/0510070.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz K. Fanburg B.L. Beasley D. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha promote growth factor-induced proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;290(6):H2528–H2534. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01077.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.B. Harris R.C. Autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine signaling by EGFR ligands. Cell Signal. 2005;17(10):1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soifer S.J. Kaslow D. Roman C. Heymann M.A. Umbilical cord compression produces pulmonary hypertension in newborn lambs: a model to study the pathophysiology of persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn. J. Dev. Physiol. 1987;9(3):239–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark K.R. Fasules J. Hyde D.M. Voelkel N.F. Henson J. Tucker A. Wilson H. Reeves J.T. Severe pulmonary hypertension and arterial adventitial changes in newborn calves at 4,300 m. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987;62(2):821–830. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.2.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tod M.L. Cassin S. Thromboxane synthase inhibition and perinatal pulmonary response to arachidonic acid. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985;58(3):710–716. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A. Rhodes J. Role of vascular smooth muscle in the development of high altitude pulmonary hypertension: an interspecies evaluation. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2001;2(2):173–189. doi: 10.1089/152702901750265288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel R.C. Sylvester J.T. Gender differences in hypoxic vascular response of isolated sheep lungs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1983;55(1 Pt 1):100–104. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild L.M. Nickerson P.A. Morin F.C., III Ligating the ductus arteriosus before birth remodels the pulmonary vasculature of the lamb. Pediatr. Res. 1989;25(3):251–257. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Q. Ducsay C.A. Longo L.D. Zhang L. Effect of long-term high-altitude hypoxia on fetal pulmonary vascular contractility. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1786–1792. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01314.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Chalothorn D. Jackson L.F. Lee D.C. Faber J.E. Transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor mediates catecholamine-induced growth of vascular smooth muscle. Circ. Res. 2004;95(10):989–997. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147962.01036.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W. Ibe B.O. Raj J.U. Platelet-activating factor induces ovine fetal pulmonary venous smooth muscle cell proliferation: role of epidermal growth factor receptor trans-activation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292(6):H2773–H2781. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01018.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]