Abstract

Purpose:

To quantify gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients’ preferences for reducing treatment toxicities and the likely effect of toxicities on patients’ stated adherence.

Methods:

English-speaking members of the Life Raft Group, a GIST patient advocacy and research organization, aged 18 years and older, completed a web-enabled survey including a series of treatment-choice questions, each presenting a pair of hypothetical GIST medication toxicity profiles. Each profile was defined by common or concerning toxicities verified via pretest interviews including: severity of edema, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, rash, hand-foot syndrome, and heart failure; and risk of serious infection. Each subject answered 13 choice-format questions based on a predetermined experimental design with known statistical properties. Subjects were asked to rate the likelihood that they would miss or skip doses of medications with different toxicity profiles. Random-parameters logit was used to estimate a relative preference weight for each level of toxicity.

Results:

173 subjects completed the survey. Over the ranges of toxicity levels included in the study, heart failure was the most important toxicity. Edema was the least important. For all toxicities, reducing severity from severe to moderate was more important to subjects than reducing severity from moderate to mild. Reducing heart failure from moderate to mild and diarrhea from severe to moderate had the largest effects on subjects’ evaluation of adherence.

Conclusions:

All toxicities included in the study are important to patients. Treating or reducing severe toxicities is much more important to patients than treating or reducing moderate toxicities. Focused reductions of certain toxicities may improve treatment adherence.

Keywords: GIST, toxicities, patient preference, adherence, conjoint analysis, discrete choice experiment

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are a type of cancer that develops in the supportive or connective tissues of the digestive system. About 60% of GISTs occur in the stomach. GISTs are rare, with an annual incidence of 5,000 patients in the United States (US) (approximately 15 per million among adults). GISTs usually occur in people aged 50 years and older. Symptoms may include stomach pain, vomiting, bloody stools, fatigue, fever, and anemia. The exact causes of GISTs remain unknown, but research has indicated that tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib and sunitinib block the tyrosine kinase enzymes that GISTs need in order to grow. While imatinib remains the standard first-line therapy in metastatic GIST, a number of second-generation or broad-spectrum TKIs including nilotinib, sorafenib, and regorafenib are currently being investigated as second-, third-, or fourth-line treatments for those patients who develop imatinib resistance.1 Imatinib, sunitinib, and other targeted agents currently in development for treating GIST are associated with toxicities that are difficult for some patients to tolerate.

For many patients these treatments have changed GIST from a fatal condition to a chronic disease requiring treatment for many years; thus, it is important to understand patients’ perceptions of these toxicities and the extent to which toxicities may affect adherence to treatment. The primary objectives of this research were to identify toxicities that are common and/or concerning for GIST patients and to elicit their preferences for avoiding toxicities associated with GIST treatments. A secondary objective was to estimate the potential impact of treatment-related toxicities on patients’ ratings of likely treatment adherence.

We identified common and concerning toxicities associated with GIST treatments. We then developed a choice-format conjoint-analysis survey to quantify the relative importance of different treatment toxicities to patients with GIST. Over the past decade, choice-format conjoint analysis – also known as discrete-choice experiment – has been used increasingly to quantify preferences for features of health, health care, and health care policy.2 Choice-format conjoint analysis, as applied to health care decision making, is a systematic method of eliciting trade-offs to quantify the relative importance patients assign to various treatment outcomes. It is based on the premise that medical interventions are composed of a set of outcomes and that the attractiveness of a particular intervention to an individual is a function of these outcomes.3,4

In a choice-format conjoint-analysis survey of preferences for pharmaceutical treatments, treatment options are defined by a set of outcomes and each of those outcomes can take on different levels (eg, severity or risk). Outcome levels are combined into treatment profiles and the profiles are assembled into a number of choice pairs. Subjects are then asked to choose their preferred alternative between two treatment profiles in a series of choice questions. The resulting pattern of choices reveals the relative importance of each treatment outcome level and can be used to quantify the relative importance of changes in the level of an outcome.

Methods

Survey sample

Study subjects were required to have a self-reported diagnosis of GIST and be aged 18 years or older. Subjects were recruited through the Life Raft Group (LRG), a GIST patient support and advocacy organization. LRG posted a link to the online survey on its website and sent an invitation to its members. All subjects were required to provide informed consent before completing the survey.

Sample-size calculations represent a challenge in conjoint analysis. Minimum sample size depends on a number of criteria, including the question format, the complexity of the choice task, the desired precision of the results, and the need to conduct subgroup analyses.5 Researchers commonly apply a rule of thumb such as the algorithm proposed by Orme6 that suggests a minimum sample size as a function of the number of choice tasks, the number of alternatives per choice task, and the highest number of levels of any attribute in the study.6 Most published conjoint analysis studies have a sample size between 100 and 300 respondents.7 One recent conjoint-analysis study that used a choice-question format similar to the one used in this study included 153 subjects.8 Therefore, the target minimum sample size for this study was 150 subjects.

Survey instrument

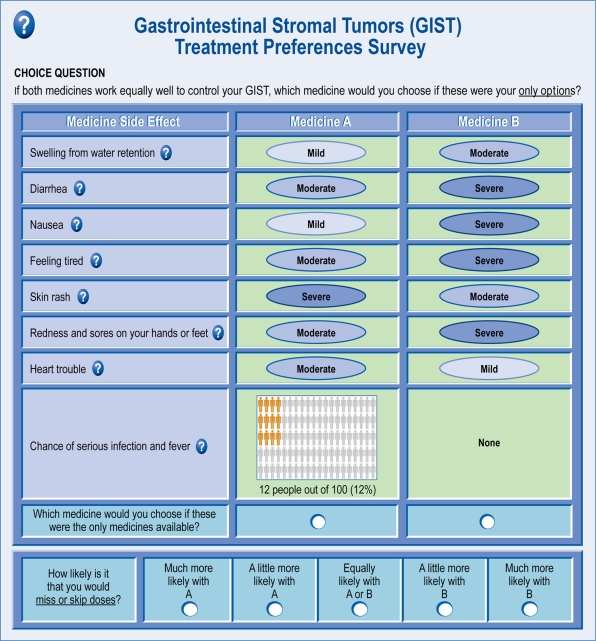

Each subject was presented with a series of 13 treatment-choice questions (Figure 1). In each treatment-choice question, subjects were asked to choose between two hypothetical GIST treatment profiles, each of which was defined by varying levels of eight treatment toxicities. Subjects were asked to assume that treatment efficacy was the same for all hypothetical treatment profiles included in the choice tasks. In addition, subjects were asked to assume that all medical bills, including the cost of medicines, were covered by health insurance. The survey instrument also elicited standard demographic information as well as a number of items about the patients’ experiences with GIST and GIST treatments.

Figure 1.

Example of a trade-off question with adherence rating follow-up question.

The eight treatment toxicities were intended to represent toxicities that are common among GIST treatments and of concern to patients. These toxicities were identified based on a review of the published literature describing toxicities associated with current GIST treatments and consultation with clinical experts. Toxicities included edema, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, skin rash, hand-foot syndrome, congestive heart failure, and serious infection with fever. For seven of the eight toxicities, toxicity levels were described as mild, moderate, or severe. For the eighth toxicity, serious infection with fever, the possible levels included 0% (None), 6%, 12%, and 25% chance of occurrence.

To estimate the potential impact of toxicities on adherence, the survey also included adherence-rating questions. After each choice question, patients who indicated that they miss or skip doses of their GIST medication at least occasionally were asked to rate the relative likelihood that they would miss or skip doses of the hypothetical treatments in the choice question (Figure 1). This likelihood was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Much more likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A” to “Much more likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine B”. The middle level on the Likert scale was “Equally likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A and Medicine B”.9,10

We conducted face-to-face, semistructured pretest interviews with a convenience sample of 5 subjects with a self-reported diagnosis of GIST who were referred by a practicing, board-certified oncologist. The pretest subjects confirmed that the toxicities included in the survey instrument were both common and concerning and that no important toxicity was excluded. These pretest interviews also were used to test subjects’ comprehension of the survey instrument and the treatment-choice and adherence-rating questions. All 5 subjects provided consistent feedback regarding the toxicities of interest and the understandability of the survey instrument.

To create treatment profiles for the choice questions, we employed a commonly used algorithm to construct an experimental design resulting in 48 choice pairs.11–15 The final experimental design consisted of four survey versions or blocks, each containing 12 choice pairs. Each subject was randomly assigned to one of the four blocks. All questions in a block were randomized for each subject. The survey was approved by RTI International’s Office of Research Protection and Ethics (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Statistical analysis

We used multivariate, random-parameters regression to estimate a relative preference weight for each treatment toxicity level. In random-parameters logit, the independent variable is treatment choice and a regression equation is used to estimate the effect of each toxicity level on the probability of choosing a given treatment alternative. Each toxicity attribute was effects coded (eg, for a 3-level attribute: 0 1, 1 0, −1 −1, such that the parameter for the omitted category is the negative sum of the included categories), rather than dummy coded (eg, 0 1, 1 0, 0 0) so that the mean effect for each outcome is normalized at zero instead of setting all the omitted categories to zero.16 Thus, the parameter estimate for each outcome level (toxicity severity or risk) is the log odds for that level. The log odds for each outcome level can be interpreted as the preference weight indicating the relative strength of preference for avoiding that toxicity level. For each toxicity, the difference between the highest and lowest preference weights represents the relative importance of avoiding that toxicity over the range of toxicity levels included in the survey.

Random-parameters logit avoids potential estimation bias from unobserved preference heterogeneity in discrete-choice models by estimating a distribution of preferences across patients for each preference parameter.17,18 In addition, because each subject provided responses to more than one choice question, we estimated a random-effects panel model to account for within-subject correlation. Statistical analyses for the choice models were conducted using NLOGIT 4.0 (Econometric Software, Inc, Plainview, NY).

The adherence-rating questions included in the survey asked patients to indicate how much more likely they would be to miss or skip doses of one treatment compared to another. One possible response to this question is “Equally likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A and Medicine B”. Choosing this response indicates that either the patient believes that he or she will not miss or skip doses with either treatment or that the outcomes of the two treatment profiles do not differ enough to induce a person to be less adherent with one treatment than with the other. In either case, choosing this response provides no information about the extent to which treatment attributes might affect adherence. Therefore, we used a Heckman two-stage model to estimate first the effect of patient characteristics on the likelihood of choosing the response, “Equally likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A and Medicine B” and then the effect of treatment toxicities on subjects’ assessment of the likelihood that he or she would miss or skip doses.9,10 In the first stage, the dependent variable indicated whether a patient chose a response other than “Equally likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A and Medicine B” and patient-specific characteristics were used as explanatory variables. In the second stage of the adherence rating model, patients’ ratings of the likelihood of missing or skipping doses was modeled as a function of treatment toxicities. Specifically, we estimated an ordered-probit model in which the levels of the treatment attributes were used to predict the likelihood of choosing an adherence rating incorporating the results of the first stage by controlling for those who indicated that treatment attributes would likely not affect treatment adherence. Statistical analyses for the adherence models were conducted using STATA 8.2 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Survey sample

One hundred and seventy-three members of LRG consented to participate and completed the survey during March 2010. The gender of the sample was distributed evenly between males and females (51% female). The majority of patients (93%) were white, and approximately 75% of patients were married. The mean age was 57 years (SD ± 12.8). Of the 173 patients, 80% indicated that they currently take an oral medication to treat their GIST. The majority of subjects (66%) rated their GIST as currently under control with treatment. Nearly all subjects in the sample (99.4%) indicated that they had previously experienced one or more of the toxicities described in the survey. The most common toxicities reported were fatigue (81.5%), edema (68.2%), and diarrhea (64.7%). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample. GIST and GIST treatment experience is summarized in Table 2. Patients’ self-reported assessment of adherence is presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Statistic or category | Subjects N = 173 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 84 (48.6%) |

| Female | 89 (51.4%) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 56.6 (12.8) |

| Marital status | Married | 129 (74.6%) |

| Widowed | 7 (4.0%) | |

| Divorced or separated | 14 (8.1%) | |

| Single | 18 (10.4%) | |

| Other | 5 (2.9%) | |

| Racial or ethnic group | White/caucasian | 160 (92.5%) |

| Asian | 9 (5.2%) | |

| Hispanic/latino | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Native American | 3 (1.7%) | |

| Country of residence | United States | 138 (79.8%) |

| Canada | 9 (5.2%) | |

| United Kingdom | 9 (5.2%) | |

| Australia | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Other | 16 (9.2%) | |

| Education | High school or secondary school certificate or equivalent | 15 (8.7%) |

| 4-year college or university degree (eg, BA, BS, BSc) or less, but more than high school or secondary school certificate or equivalent | 87 (50.3%) | |

| More than a 4-year college or university degree | 71 (41.0%) | |

| Employment status | Employed | 83 (48.0%) |

| Homemaker | 7 (4.0%) | |

| Student | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Retired | 60 (34.7%) | |

| Other | 22 (12.7%) |

Table 2.

GIST treatment experience

| Characteristic | Statistic or category | Subjects N = 173 |

|---|---|---|

| Current Health Rating (0 = worst, 100 = best) | Mean (SD) | 74.3 (20.6) |

| Time since diagnosis | Less than 6 months ago | 5 (2.9%) |

| At least 6 months ago, but less than 1 year ago | 14 (8.1%) | |

| At least 1 year, but less than 2 years ago | 19 (11.0%) | |

| At least 2 years, but less than 5 years ago | 49 (28.3%) | |

| At least 5 years ago | 86 (49.7%) | |

| Had surgery to treat GIST | Yes | 151 (87.3%) |

| No | 22 (12.7%) | |

| Currently taking medicine to treat GIST | Yes | 139 (80.3%) |

| How do you receive your GIST medicine? | Pills | 138 (99.3%) |

| Both pills and IV medicine | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Experienced Toxicities | Water retention and swelling | 118 (68.2%) |

| Diarrhea | 112 (64.7%) | |

| Nausea | 83 (48.0%) | |

| Feeling tired | 141 (81.5%) | |

| Skin rash | 76 (43.9%) | |

| Redness and sores on hands and feet | 39 (22.5%) | |

| Heart trouble | 27 (15.6%) | |

| Hospitalized from serious infection | 15 (8.7%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.06%) | |

| Who do you turn to when you have toxicities from your GIST medicine? (Multiple responses were possible.) | My GIST doctor (a specialist) | 150 (86.7%) |

| My regular doctor (primary care physician) | 42 (24.3%) | |

| A nurse | 15 (8.7%) | |

| A pharmacist | 6 (3.5%) | |

| Another specialist (such as a dermatologist) | 12 (6.9%) | |

| Other people with GIST | 52 (30.1%) | |

| Other | 24 (13.9%) | |

| None of the above | 3 (1.7%) |

Abbreviations: GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumors; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

GIST treatment adherence experience

| Characteristic | Statistic or category | Subjects N = 173 |

|---|---|---|

| About how often would you say you miss or skip a dose of your GIST medicine? | Never | 92 (53.2%) |

| Less than once per month | 51 (29.5%) | |

| Between 2 and 5 times per month | 21 (12.1%) | |

| More than 5 times per month | 6 (3.5%) | |

| Missing | 3 (1.7%) | |

| Which of the following statements describes the reasons you might miss or skip doses of your GIST medicines? (Check all that apply.) | N | 78 |

| I sometimes stop taking my GIST medicine when I am sick with another illness such as a stomach illness or the flu. | 24 (30.8%) | |

| I take a lot of medicines every day, and it can be difficult to keep track of them. | 6 (7.7%) | |

| I sometimes forget to take my medicines because I am busy working, taking care of children, or participating in other activities. | 36 (46.2%) | |

| I do not take my GIST medicine when I have things to do (such as traveling or working) so that the toxicities will not interfere with these activities. | 15 (19.2%) | |

| I sometimes don’t think the medicine is working well, so it isn’t worth taking. | 3 (3.8%) | |

| I sometimes don’t like the toxicities of my medicine and take it less often to avoid or reduce these toxicities. | 14 (17.9%) | |

| I stop taking the medicine sometimes because I am having toxicities and my doctor tells me to stop the medicine until the toxicities go away. | 17 (21.8%) | |

| I sometimes find it difficult to pay for my medicines and wait to refill my prescriptions until I have the money. | 2 (2.6%) |

Abbreviation: GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

Twelve patients did not answer all of the choice questions. Only complete data was included in the analysis.

Preference weights

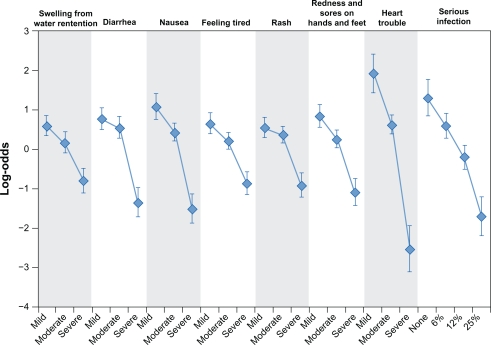

Figure 2 presents the preference weights for all toxicity levels. More-preferred outcomes have higher preference weights than less-preferred outcomes. The estimated preference weights for all eight toxicities were consistent with the natural ordering of the categories where better clinical outcomes were preferred to worse clinical outcomes. The vertical bars around each mean parameter estimate represent the 95% confidence interval. If the confidence intervals do not overlap for adjacent levels within a particular attribute, the mean estimates are significantly different from each other at the 5% level. For example, the preference weights for the levels of nausea severity are all significantly different indicating that mild nausea is significantly preferred to moderate nausea which, in turn, is significantly preferred to severe nausea. In contrast, the mean preference-weight estimates were ordered correctly for skin rash, but the statistical significance of the difference between the preference weight for mild and moderate levels cannot be readily assessed by looking at the figure. In this case, preferences for avoiding mild and moderate skin rash are not statistically different at the 95% confidence level (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Preference weights.

The vertical distance between adjacent preference weights represents the relative importance of moving from one level of an attribute to an adjacent level of that toxicity. For example, the relative importance of an improvement in moderate nausea to mild nausea is approximately 0.7 (approximately 0.4–1.1). Likewise, an improvement from severe skin rash to moderate skin rash has a relative importance of approximately 1.3 (approximately −0.9–0.4). Therefore, an improvement from severe skin rash to moderate skin rash was approximately 1.9 (1.3/0.7) times as important to subjects as an improvement from moderate nausea to mild nausea. Over the range of levels of each toxicity in the study, congestive heart failure was the most important toxicity. The remaining toxicities were ranked in order of importance as follows: serious infection, nausea, diarrhea, hand-foot syndrome, fatigue, skin rash, and edema.

Adherence ratings

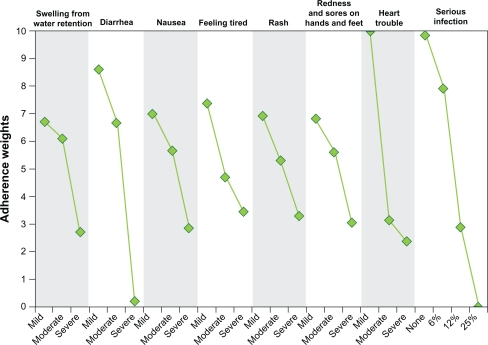

The first stage of the adherence rating model indicated that patients who discuss treatment toxicities with other GIST patients and patients who had had prior surgery to treat GIST were more likely to choose something other than “Equally likely to miss or skip doses with Medicine A and Medicine B”. In contrast, married patients and patients who discussed treatment toxicities with a pharmacist or specialist were less likely to indicate that treatment toxicities will affect the likelihood of missing or skipping doses than patients without prior treatment experience. We found no effect of employment on the likelihood that a patient would miss or skip doses. In the second stage of the model, all toxicities had an impact on the likelihood of missing or skipping doses. The effect of each toxicity level on likely adherence is presented in Figure 3. Reducing the severity of congestive heart failure from moderate to mild and reducing the severity of diarrhea from severe to moderate had the largest effect on likely adherence. Reducing the likelihood of serious infection from 12% to 6% had the third largest effect on likely adherence. In contrast, reducing the severity of edema from moderate to mild had the smallest effect on likely adherence.

Figure 3.

Adherence weights.

Discussion

The primary objectives of this research were to identify toxicities that are common and/or of concern to people with GIST and to elicit patient preferences for avoiding toxicities associated with GIST treatments. All toxicities included in the survey are important to patients with GIST. Treating or reducing the severity of toxicities from severe to moderate generally was more important to subjects than reducing severity from moderate to mild. This preference implies that treating or reducing severe toxicities was much more important to subjects than treating or reducing moderate toxicities.

A secondary objective was to estimate the potential impact of treatment-related toxicities on patients’ ratings of likely treatment adherence. For subjects who reported missing or skipping treatment doses in the past, toxicities included in the survey were rated as being likely to affect adherence. Congestive heart failure, serious infection and fever, and diarrhea were the toxicities rated as being most likely to affect adherence. Because the sample size in this study was chosen to estimate preference weights and not adherence weights and because a large majority of subjects reported not being willing to miss or skip treatment doses under any circumstance, the adherence weights presented in this study have very large confidence intervals. Therefore, the adherence results presented in this study should be viewed with caution. Further study will be required to determine whether toxicities are likely to have a statistically significant effect on subjects’ rating of likely adherence.

While choice-format conjoint analysis methods are widely used in health economics to elicit preferences for treatment features and outcomes, they have limitations. One inherent limitation is that subjects evaluate hypothetical treatments. These constructed choice questions are intended to simulate possible clinical decisions but do not have the same clinical, financial, and emotional consequences as actual decisions. Thus, differences can arise between stated and actual choices. We have attempted to minimize such potential differences by offering alternatives that mimic real-world trade-offs as closely as possible. In addition, some health professionals are skeptical that people have sufficient understanding of treatment information to competently evaluate treatment alternatives. Diagnosis among subjects in this study was self-reported and not confirmed by physician consultation or chart review. However, we believe it unlikely that people without GIST would complete this type of study because the study is cognitively challenging and requires an investment in time, in exchange for little personal gain.

Subjects in this study were recruited through a patient support and advocacy organization. These subjects appear more highly educated than the general population and the majority were diagnosed with GIST at least 5 years prior to completing the survey. Therefore, the results of this study likely are not generalizable to all GIST patients, but reflect the preference of patients who are experienced and active in the treatment of the disease.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that people with GIST have clear and measurable preferences for reducing toxicities associated with GIST treatments. Discussing treatment toxicities with patients and treating those toxicities that are most important to patients may enable physicians and other health care professionals to reduce the effect that treatment toxicities have on patients’ quality of life. The adherence results presented in this study suggest that treatment toxicities may affect treatment adherence. Understanding the extent to which toxicities may affect adherence can help health care professionals manage GIST treatments and improve treatment adherence.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, NJ, USA.

References

- 1.Montemurro M, Bauer S. Treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor after imatinib and sunitinib. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011. Apr 23, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bridges JFP, Kinter ET, Kidane L, Heinzen RR, McCormick C. Things are looking up since we started listening to patients: trends in the application of conjoint analysis in health 1982–2007. Patient. 2008;1(4):273–282. doi: 10.2165/01312067-200801040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan M, McIntosh E, Shackley P. Methodological issues in the application of conjoint analysis in health care. Health Econ. 1998;7(4):373–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199806)7:4<373::aid-hec348>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments. In: Fayers P, Hays R, editors. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 431–445. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louviere J, Hensher D, Swait J. Stated Choice Methods: Analysis and Application. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univeristy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orme BK. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Madison (WI): Research Publishers LLC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall D, Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health – how are studies being designed and reported? An update on current practice in the published literature between 2005 and 2008. Patient. 2010;3(4):249–256. doi: 10.2165/11539650-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Watson ME, Johnson FR, Hernandez JE. Benefits, risk, and uncertainty: preferences of antiretroviral-naïve African Americans for HIV treatments. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(1):29–34. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Johnson FR, Falvey H. Treatment preferences and medication adherence of people with type 2 diabetes using oral glucose-lowering agents. Diabet Med. 2009;26(4):416–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauber AB, Mohamed AF, Beam C, Medjedovic J, Mauskopf J. Patient preferences and assessment of likely adherence for hepatitis C virus treatments. J Viral Hepat. 2010. Jun 22, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Huber J, Zwerina K. The importance of utility balance in efficient choice designs. J Market Res. 1996;33:307–317. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanninen B. Optimal design for multinomial choice experiments. J Market Res. 2002;39:214–227. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zwerina K, Huber J, Kuhfeld W. A general method for constructing efficient choice designs Durham (NC): Fuqua School of Business, Duke University, 1996. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.31.9438&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed March 9, 2009.

- 14.Dey A. Orthogonal Fractional Factorial Designs. New York: Halstead Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhfeld W, Tobias F, Garratt M. Efficient experimental design with marketing research applications. J Market Res. 1994;31:545–557. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Train K. Discrete Choice Methods with Simulation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. Mixed logit; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Train K, Sonnier G. Mixed logit with bounded distributions of correlated partworths. In: Scarpa R, Alberini A, editors. Applications of Simulation Methods in Environmental and Resource Economics. Dordrecht: Springer Publisher; 2005. pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]