Abstract

Aims: Planning a career in general practice depends on positive attitudes towards primary care. The aim of this study was to compare attitudes of medical students of a Modern Curriculum at Hannover Medical School with those of the Traditional Curriculum before (pre) and after (post) a three-week clerkship in general practice. In parallel, we aimed to analyse several other variables such as age and gender, which could influence the attitudes.

Methods: Prospective survey of n=287 5th-year students. Attitudes (dependent variable, Likert-scale items) as well as socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, rural/urban background), school leaving examination grades, former qualifications, experiences in general practice and career plans were requested. Attitudes were analysed separately according to these characteristics (e.g. career plans: general practitioner (GP)/specialist), curriculum type and pre/post the clerkship in general practice. Bi- and multivariate statistical analysis was used including a factor analysis for grouping of the attitude items.

Results: Most and remarkable differences of attitudes were seen after analysis according to gender. Women appreciated general practice more than men including a greater interest in chronic diseases, communication and psychosocial aspects. The clerkship (a total of n=165 students of the “post” survey could be matched) contributed to positive attitudes of students of both gender, whereas the different curricula did not show such effects.

Conclusions: Affective learning goals such as a positive attitude towards general practice have depended more on characteristics of students (gender) and effects of a clerkship in general practice than on the curriculum type (modern, traditional) so far. For the development of outcomes in medical education research as well as for the evolution of the Modern Curriculum such attitudes and other affective learning goals should be considered more frequently.

Keywords: medical education research, general practice, curriculum, attitudes, questionnaire

Abstract

Zielsetzung: Das Berufsziel „Allgemeinarzt“ ist abhängig von einer positiven Einstellung zum Fach Allgemeinmedizin. Ziel dieser Studie war es, solche Einstellungen von Studierenden des Modellstudiengangs in Hannover mit denen des Regelstudiengangs jeweils vor und nach dem Blockpraktikum Allgemeinmedizin zu vergleichen. Zusätzlich wurde eine Reihe anderer Variablen betrachtet (z.B. Alter, Geschlecht), von denen die Einstellungen abhängig sein könnten.

Methodik: Längsschnittliche Befragung von n=287 Studierenden im 5. Studienjahr. Neben den Einstellungen (abhängige Variable, Likert-Skalenwerte) wurden soziodemographische Merkmale (Alter, Geschlecht, Herkunft), Abiturnote, Berufsabschlüsse, Erfahrungen in der Allgemeinmedizin und Karrierepläne erfragt. Die Auswertung der Einstellungsitems erfolgte getrennt nach allen diesen Merkmalen (z.B. Karrierepläne: Berufsziel Allgemeinarzt/Spezialist) sowie nach Art des Studiengangs (Modell, Regel) und im prä-/post-Vergleich mittels bi- und multivariater statistischer Testverfahren. Zur Gruppierung der Einstellungsitems wurde eine Faktorenanalyse durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse: Die meisten und bemerkenswertesten Einstellungsunterschiede fanden sich bei der Auswertung getrennt nach Geschlecht. Frauen haben das Fach stärker wertgeschätzt und zeigten ein größeres Interesse an chronischen Krankheitsverläufen, Gesprächsführung oder psychosozialen Zusammenhängen. Das Blockpraktikum (n=165 zugeordnete Befragte zum Zeitpunkt „post“) hat zu einer positiven Entwicklung der Einstellung bei Studierenden beider Geschlechter beigetragen, wohingegen sich Studierende des Modell- bzw. Regelstudiengangs in ihren Einstellungen nicht unterschieden.

Schlussfolgerung: Das affektive Ausbildungsziel einer wertschätzenden Haltung gegenüber dem Fach Allgemeinmedizin ist in Hannover bislang weniger vom Gesamtcurriculum (Modell, Regel) als von Eigenschaften der Studierenden (Geschlecht) und Effekten des Blockpraktikums abhängig. Für die Entwicklung von Outcomes in der Ausbildungsforschung und bei der Weiterentwicklung des Modellstudiengangs sollten Einstellungen und andere affektive Lernziele stärker berücksichtigt werden.

Introduction

Determinants of attitudes towards general practice and career plans

In many disciplines the shortage of doctors is increasingly visible, and currently general practice faces a deficit [1]. This trend of an increasing shortage of people interested in the profession of general practice is also being discussed in other countries such as Great Britain, Israel and Canada [2], [3], [4]. Thus, there have been foreign studies on the influences on the career goal of being a general practitioner (GP) and general attitudes of students towards general practice [5]. For career plans and professional impressions of the intrinsic job characteristics, factors such as the belief that it is interesting or work conditions [6], [7] as well as socio-demographic factors such as gender [2], [3], [8] and origin [5] have been identified. In addition, the medical education at Medical Schools is understood to be an important factor in the influence of role models [3] as well as establishing a fundamental appreciation of the discipline of general practice [4], [9], [10]. Consequently, the (extended) duration of general practice clerkships [3]) as well as longitudinally aligned modules [3], [11] could have a positive impact on the attitude towards general practice. The positive attitudes of a clinical instructor or faculty towards the importance of primary care may also contribute to a positive attitude of students.

Learning objectives and curricular strengths in the Modern Study Programme in Hannover

Currently national competency-based learning objectives (NKLM) are developed in Germany [12]. In fact, learning objectives should not only indicate knowledge attainment but also higher levels of competence towards "affective" learning objectives [13]. A positive attitude towards general practice as an (ideal) objective of an overall curriculum or important prerequisite would be to highlight the career of GP. In Germany in accordance with current educational law Modern Study Programmes are increasingly being established [14] and optimal “primary care” educational objectives are to be found; in Hannover [http://www.mh-hannover.de/15564.html] there are to be, for example,

doctors trained in routine medical practice

students learning and thinking across disciplines,

teaching of psycho-social skills,

application of the acquired knowledge in the basic care of patients

health economic aspects taken into account,

students learning to competently recognise and treat general medical illnesses.

Compared to the Traditional Study Programme in Hannover, which has gradually been replaced with the Modern Study Programme since the academic year 2005/2006, there have been logical curricular changes to achieve the objectives listed above. For example in the first year, interdisciplinary patient-oriented learning is achieved in a total of five one-week preparatory courses on clinical topics such as breast cancer or back pain. Communication skills are already taught in the 2nd academic year and more intensely than previously. The proportion of clinical references, such as in the anatomy module, have been increased by example via additional patient screening. It is through the constant repetition of the course content with progressive learning that facilitates the retention of knowledge. Thus, in the eight-week interdisciplinary course "Differential diagnosis and therapy" including the subject of general practice in study year 5, important diseases are repeated once again1.

Study objectives

Taken together, it seems that a positive assessment of the discipline of general practice and ultimately aspirations to be a GP depends on multiple factors such as personal preresquisites as well as the specifics of the training in each facuety. This includes a positive environment for the discipline as well as unique features of the curriculum (length, extent of the clerkship). The differences nationally and internationally concerning this are large, and in Germany studies of high methodological quality are lacking. This is the objective of the present work. Students in both the Traditional and the Modern Study Programmes were surveyed before and after completion of general practice training in the 5th academic year in Hannover. Their impressions of the discipline of general practice and additional possible determinants, such as socio-demographic characteristics, were assessed.

Methods

Study Design, Participants and procedure

The study design consisted of a longitudinal survey of attitudes towards general practice in the form of a written survey at the Medical School of Hannover. Every student in the 5th Academic year was asked to fill out the survey a total of two times, namely, before (the questionnaire time point "pre") and after ("post") the three-week general practice clerkship. The students asked to participate covered five consecutive terms in the academic years 2008/2009 (i.e. from the 2nd term of 3 terms starting February 2009) and 2009/2010 (to the 3rd term of 3 terms, i.e. June 2010) (altogether n=423 training participants). In the first two "survey terms" (academic year 2008/2009) the students were all taught according to the Traditional Study Programme; from the beginning of the academic year 2009/2010 students ware mainly in the Modern Study Programme, but some of the students had completed the Traditional Study Programme as they had entered the 5th Academic year "late".

The survey was always on day 1 of the general practice training before the start of the introductory lecture in the lecture hall. Students were handed a questionnaire on arrival (see Section Design of Questionnaire) and details regarding it were explained when they had all arrived. The questionnaire was then immediately filled out and collected. About two weeks after the end of the three-week training, the “post”-questionnaire was distributed at the end of the rehabilitation medicine exam (attendance n = 385/423 [91%] attendees of the earlier general practice training), was again immediately filled out and collected.

The study project was submitted to the chairman of the ethics committee at the Medical School of Hannover and approved (No. 611).

Design of the questionnaire

The "pre" and "post" questionnaire each had 40 identical attitude assessing attitude items over 2 pages. These reflected the peculiarities of the German education and health system and represented a suitable selection of questionnaire items from the (partially validated) English literature [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. They were translated into German and in discussion with colleagues at the Institute of General Practice (academic staff i.e. doctors, health scientists, psychologists) adapted to accommodate the local culture. The items were then translated back into English in order to detect any inadvertent alterations to the meaning that might have arisen through the initial translation into German. In addition, a few items were generated independently (for example, the statement: "The care of geriatric patients is less interesting to me."), so that an altogether new, modified instrument was developed. The above items showed uniform Likert-scales with level 1 (not true), 2 (disagree somewhat), 3 (sometimes), 4 (agree somewhat), 5 (true).

Along side the above questions, the "pre" questionnaire included a number of socio-demographic determinants for the students such as age, sex, origin (e.g. country, city) as well as details of final secondary school leaving examination results, previous qualifications, career plans (intended field of study), experience in general practice (e.g. clerkship), Traditional or Modern Study Programme, and whether they had transferred from other medical schools. The "post" questionnaire again included the question covering career plans and changes to this connected with the general practice clerkship.

Linking students’ questionnaires from the two survey time points was enabled through use of a code, which contained their mother’s initials as well as her birthday.

Statistical analysis

The socio-demographic characteristics and all other data were presented with descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation [SD], frequency in [%]).

For the purpose of reducing or grouping the attitude items, factor analysis (principal components analysis, varimax rotation) was performed. Only factors with Eigenvalues ≥ 1 (Kaiser criterion) were extracted.

The analysis of baseline data of all participants was achieved by stratification according to the Traditional Study Programme and Modern Study Programme as well as by socio-demographic information and all other data using descriptive statistics (shown from mean values of Likert-scale values ± SD) and by the Mann-Whitney U test (for career plans [division into three groups]: Kruskal-Wallis test).

In addition, the pre-/post- results of all paired student questionnaires were presented descriptively (mean values of Likert-scale values ± SD) and by the Wilcoxon test for statistical evaluation. Using multifactorial variance analysis (ANOVA; target variable: item difference) the nature of the course and other possible factors were also taken into account.

For univariate statistical tests we corrected according to Bonferroni. For n=40 items the level of significance was therefore set to p=0.05/40=0.00125.

Results

Characterisation of the participants

The total survey sample in the 5 terms was n=287 participants (baseline data, representing a response rate of 67.8%), n=171/2852 students (60.0%) completed the Traditional Study Programme, n=89/285 (31.2%) finished the Modern Study Programme (the remainder corresponds to transfers between different Medical Schools). For the second survey time point there were n=165/287 (57.5%) participants that could be matched with the first survey according to the pair code; n=106/165 (64.2%) belonged to the Traditional Study Programme, n=48/165 (29.1%) to the Modern Study Programme.

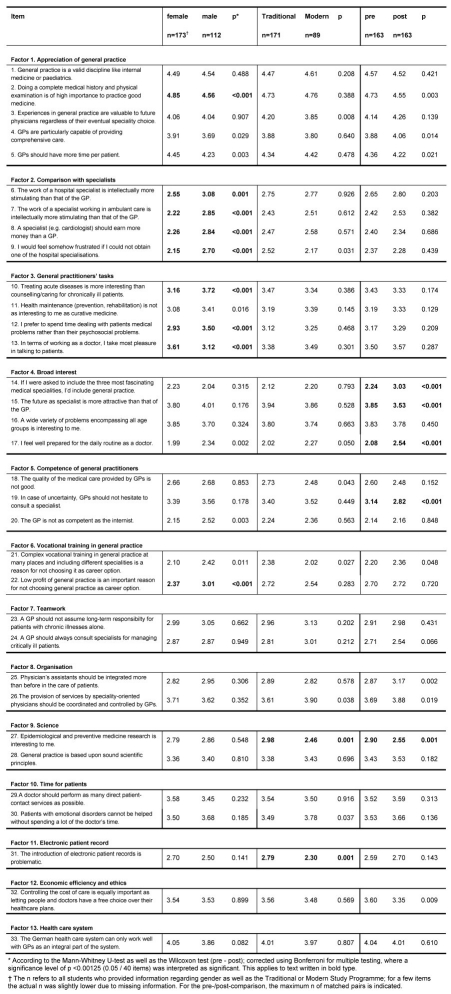

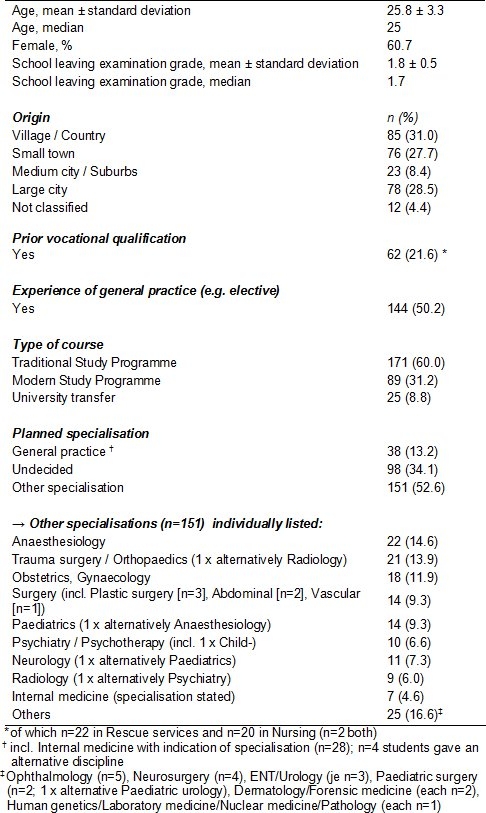

The socio-demographic characteristics and other details such as previous experience of general practice or career plans are summarised in Table 1 (Tab. 1) (baseline data).

Table 1. Socio-demographic data and planned specialisation (total n = 287; in case of missing values, 100% refers to the valid total).

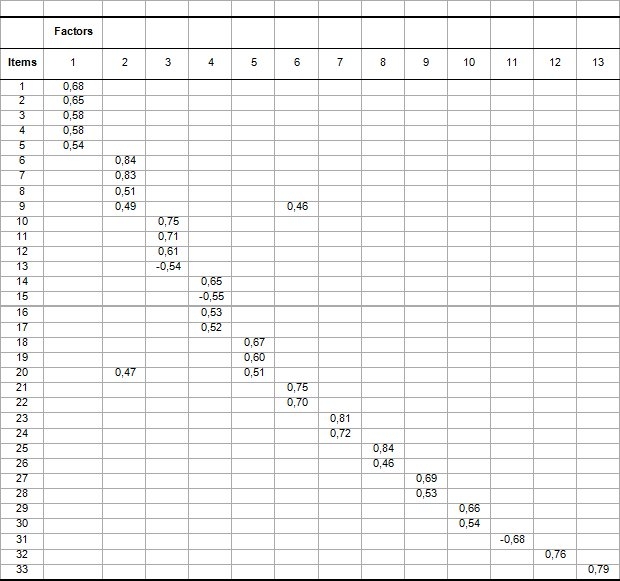

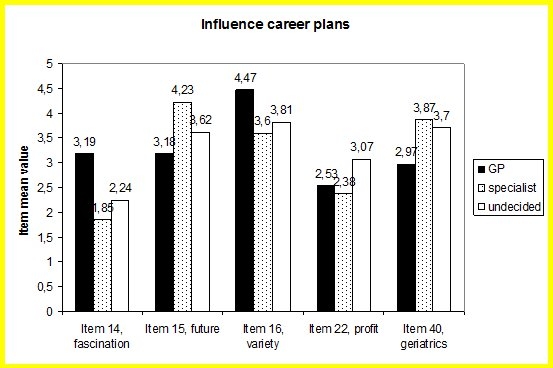

Factor Analysis

To better present the study results (see Table 2 (Tab. 2)), the attitude items were grouped by factor analysis (themes) and renumbered accordingly. The results of the factor analysis with the "loadings" (correlation coefficients) of each variable (item) on a specific factor is shown in Table 3 (Tab. 3). The factor descriptions in Table 2 (Tab. 2) have been generated by interpretation using those questions with scores > 0.5 (convention). Some questions did not show sufficiently high correlation with one of the themes and these are shown separately in Table 4 (Tab. 4).

Table 2. Representation of the mean Likert scale scores (1 [not true] to 5 [true]) of the questions after extraction of the 13 themes (factor analysis) pre and post general practice training according to gender and Traditional or Modern Study Programme. For space reasons, the items have partially been shortened.

Table 3. Representation of the component matrix after extraction of the 13 themes (factor analysis). The values correspond to the factor loadings (Pearson r correlation coefficient), correlations <0.45 are not displayed. For the description of the items (rows) and the interpretation of the factors (columns) see Table 2.

Table 4. Representation of the mean Likert scale scores (1 [not true] to 5 [true]) of the questions (not grouped according to factors/themes). Same comments and legend as Table 2.

The sample proved to be very well suited to factor analysis (MAS [Measure of Sampling Adequacy]=0.80). Factor analysis yielded n=13 mostly well-interpretable questionnaire themes, which explained 59.6% of the total variance.

Evaluation of the Baseline Data

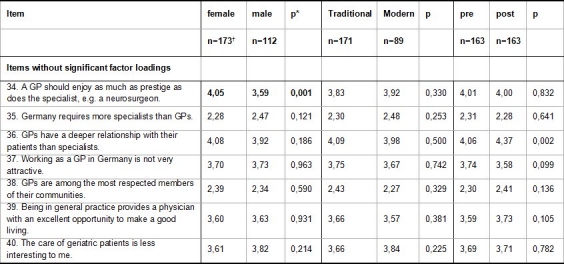

The analysis of baseline data by gender showed a remarkable, statistically significant difference in a large number of the attitude questions (see Table 2 (Tab. 2) and Table 4 (Tab. 4)). The analysis separated by the Traditional and Modern Study Programmes (without medical school transfers) resulted in significantly fewer questions with statistically significant differences. Different career plans were significantly associated with particular attitudes (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1), presentation of the statistically significant results).

Figure 1. Graph showing statistically significant attitude differences in the baseline data examined according to the planned specialisation (AM = general practice or internal medicine with no details provided of specialization); Representation of all items with p<0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis test). For a more detailed explanation of the items see Table 2.

All other analyses for the initial survey (separated by age [dichotomised by the mean value], secondary school leaving exam grade [dichotomised by the mean value], origin [country, city], former professional qualifications [yes, no], prior experience in general practice [yes, no]) showed virtually no differences, as based on a significance level adjusted according to Bonferroni. However, question 24 ("A GP should always consult specialists for managing critically ill patients.") was described by students originally from the city as more accurate (Likert mean value: 3.31) than by students coming from the country (2.50, p<0.001); question 18 ("The quality of medical care provided by GPs is not good.", see Table 2 (Tab. 2)) was judged more accurate by students with a vocational qualification (3.18) as opposed to students not vocationally trained (2.53, p<0.001).

Changes after the general practice clerkship

The general practice clerkship itself (pre-/post-analysis) had an influence on some items, but as measured by the number of significantly modified items it was less apparent than gender; the corresponding results are integrated into Table 2 (Tab. 2) and Table 4 (Tab. 4).

In addition to bivariate analysis, multivariate analysis was used to investigate whether pre-/post-differences were dependent on items representing other themes such as socio-demographics. Regarding this there were only a few isolated instances. For example of the statistically significant items with changes over time, only question 14 ("If I were asked to include the three most fascinating medical specialities, I'd include general practice.", an increase in agreement over the time period) was additionally dependent on gender (p=0.006) and the type of the course (p=0.043). With respect to gender, the pre-/post-difference was larger for men than for women (Δ=1.15 versus Δ=0.60), with regard to the type of course the difference was larger for the Traditional Study Programme than the Modern Study Programme (Δ=0.83 versus Δ=0.52).

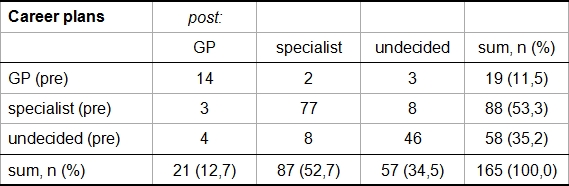

A proportion of the participants (40%) at the second survey time point affirmed that the general practice training had contributed to a change in their further education and training plans. This was expressed predominantly in positive free text entries (e.g. general practice "more interesting than thought" or "is now an alternative"). However, in comparison to the pre-training questionnaire, there were no decisive effects on definite career plans (see Table 5 (Tab. 5)).

Table 5. Pivot table showing the career plans before (pre) and after (post) the general practice training (GP = general practice or internal medicine with no details provided of specialization), n = 165 (paired sample).

Description of a single notable observation

Question 17 ("I feel well prepared for the daily routine as a doctor.") does not belong to the specific attitude items. It was incorporated as a free item in order to monitor the Modern Study Programme and the general practice training with regard to perceptions of self-efficacy. The value of this item in comparison to almost all other items was notably low (i.e. the students felt less prepared for routine medical practice). Although the nature of the course did not influence this, the general practice clerkship had the effect that the students felt better prepared (see Table 2 (Tab. 2)).

Discussion

Summary

Our analysis of a large number of parameters relating to the attitudes of medical students towards general practice has shown that the most, and noteworthy differences were gender specific. Women valued the subject more highly and showed more interest in chronic disease processes, communication skills or psychosocial conditions. Opinions were less frequently influenced by the curriculum of the Modern Study Programme or the general practice training. In contrast to a positive effect of the training on self-efficacy (the feeling of good preparation for medical practice), no effect for the Modern Study Programme could be found. While the training led to a greater interest in general practice, it didn’t really affect decisions to become a GP.

Comparison with the literature

The career choice of "general practice/internal medicine (without specialisation)” was given by 13.2% of the respondents to our survey; only 3.5% of the respondents explicitly stated “GP”. This choice was made to the same question in a previous study [20] of first year students by 4.9% (women) and 6.7% (men). In a recent multi-centre, longitudinal study 9,7% of respondents at the end of the final so-called “practical year” planned to work as GP [21]. Thus, our own results show that Germany is clearly comparable.

As discussed above, a range of curricular-related factors were identified in some older studies from abroad that have an influence on whether to become a GP. Specifically, a six-week medical clerkship [15] in the third year was found to influence undecided students towards a career in general practice. Recent studies from Germany (including this one) show a similar trend of a positive attitude towards general practice after completion of a general practice practical training course [22], [23]; these studies, however, used broader and less specific survey instruments (similar to, for example a standard evaluation [23]).

Some discrepancies were found when comparing the results of individual items from our own survey with those obtained from the United States [15], [16]. The change (after general practice training) was however generally similar. For example, question 11 ("curative medicine more interesting") was denoted abroad prior to the training more strongly as "not true", and afterwards - comparable to our own data - as true. Similarly, question 12 ("Organ medicine preferred to psychosocial issues") was initially marked as “not true”, whereas after the practical it was evaluated as “true” similarly or even more so than in our own findings. These and other examples (related to the different health systems and curricula) suggest that abroad there is an initial greater "openness" and appreciation of general practice. Since the estimates after the training approached our own, they seem to be unstable in everyday experience. As our own survey was conducted later (i.e. in the 5th study year), it is plausible that the results of the initial survey have been influenced by experiences gained earlier.

A greater "motivation" for men for the discipline of general practice during the training [22] was noticeable in our investigation as an increased “fascination” for the discipline (question 14). In other words, their negative "prejudices" were greater, but so was the simultaneous change over time. Some studies from other countries [2], [3], [8] also associated the female sex with a generally positive attitude towards general practice and similar professional options.

Strengths and Weaknesses

After completing a clerkship, disciplines are often rated better so, at least in the short term, positive effects can be measured, but the sustainability of such effects is less well known. A study from Canada showed greater interest in general practice at the beginning of the study, which was quickly reduced in the 2nd academic year and only slightly increased toward the end of the degree; another study in Great Britain (a cross-sectional study similar to [24]) showed that impressions were more positive than at the start [2]. This is one of the weaknesses of our investigation - we tracked students only for a relatively short period of time. This though was still over a longer period of time than for previous similar studies in Germany. As students at the end of their 5th year begin the practical year, they would be impossible to follow without the provision of (email) addresses and this would have removed the anonymity.

The responder rates of 68% (pre) and 58% (post, linked after matching to the pre) are relatively low, but higher than most email-conducted evaluations or surveys in the Hannover Medical School (MHH) [personal communication from the Dean]. It is conceivable that students with negative experiences in the general practice clerkship would not participate in the post-survey, with the effect that the pre-/post- effects would be even lower. Ultimately, this may generate the possibility of bias. With respect to the transferability of our results, knowledge of the general attitude of the faculty towards general practice ("hidden curriculum") would be important, something which was not included in our study within the modelling of covariates of the attitudes of students.

In retrospect, some items were not optimally designed. Some questions for example contain more than one statement ("Research on epidemiological and preventive aspects"), and the questionnaire was ultimately not sufficiently validated. The scope of the questionnaire in its present form renders it an impractical instrument for continued use in education research. The further development of the questionnaire is thus an important task. This applies equally to the development of new instruments (quality indicators) that represent an affective learning objective such as a "positive attitude towards general practice”. The approach to detect such an outcome measure by comparing two curricula, however represents the real strength of our work.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it should be emphasised that the affective educational objective of a positive attitude towards the general practice has been more dependent on the characteristics of students (gender) and (possible short-term) effects of the general practice training. This is in spite of the introduction of the Modern Study Programme in Hannover with more courses in general practice core competencies. The extent to which particular changes in the overall curriculum could actually influence and have beneficial effects on the outcome of a positive attitude towards general practice cannot be answered by this current study. Nevertheless, affective learning objectives should be considered during further development of various teaching formats of the Modern Study Programme. With regard to this, the extensive course in the 2nd year covering communication skills could again be adopted and strengthened in further study courses (currently only in the general practice training) [25]. Against the background of the literature described above and our own results with regard to the effects of the training, earlier general practice experience in particular or a longitudinal general practice track could be beneficial [26]; this could positively influence the perception of general practice, as opposed to being shaped by the image of students "already greatly influenced by highly specialised care" [27].

The results of this study should inform clinical lecturers in education of the different positions of men and women and thereby aim to promote certain characteristics or attitudes in particular cases. In general, the development of outcomes in education research should consider attitudes and other affective learning objectives more seriously in the future.

Notes

1 For the current study, only the differences of the first two years (previously: pre-clinical phase) are relevant, as the change in the curriculum later in the second study phase also affected students in the traditional study programme.

2 n=2 missing information about the type of the study programme

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the students for participating and completing the questionnaire, and Daniela Antic (Dean's Office, Supervisor 5th year) for organisational support. The study was carried out as part of the Master of Medical Education (MME-D); participation has been supported through the Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft and the Medical School of Hannover.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Joos S, Szecsenyi J. Bessere Vernetzung soll den Hausärztemangel bekämpfen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2009;106(14):A652–A653. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson E, Berlin A, Fuller J. Attitude of medical students towards general practice and general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(478):359–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tandeter H, Granek-Catarivas M. Choosing primary care? Influences of medical school curricula on career pathways. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(12):969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott I, Wright B, Brenneis F, Brett-MacLean P, McCaffrey L. Why would I choose a career in family medicine? Reflections of medical students at 3 universities. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(11):1956–1957. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(6):502–512. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiorova T, Stevens F, Scherpbier A, van der Zee J. The impact of clerkships on students' specialty preferences: what do undergraduates learn for their profession? Med Educ. 2008;42(6):554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03008.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolhurst H, Stewart M. Becoming a GP - a qualitative study of the career interests of medical students. Aus Fam Physician. 2005;34(3):204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson SR, Hoban JD, Mazmanian PE. Understanding primary care residency choices: a test of selected variables in the Bland-Meurer model. Acad Med. 2004;79(10 Suppl):36–39. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00011. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200410001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furmedge DS. General practice stigma at medical school and beyond - do we need to take action? Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(553):581. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X319774. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X319774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J, Kutob R. Comments heard by US medical students about family practice. Fam Med. 2003;35(8):573–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howe A, Ives G. Does community-based experience alter career preference? New evidence from a prospective longitudinal cohort study of undergraduate medical students. Med Educ. 2001;35(4):391–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00866.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn EG, Fischer MR. Nationaler Kompetenzbasierter Lernzielkatalog Medizin (NKLM) für Deutschland: Zusammenarbeit der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA) und des Medizinischen Fakultätentages (MFT) GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2009;26(3):Doc35. doi: 10.3205/zma000627. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press; 1998. pp. 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Approbationsordnung für Ärzte vom 27.06.2002. Bundesgesetzbl. 2002;1(44):2405–2435. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duerson MC, Crandall LA, Dwyer JW. Impact of a required family medicine clerkship on medical students’ attitudes about primary care. Acad Med. 1989;64(9):546–548. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198909000-00014. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-198909000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erney S, Biddle B, Siska K, Riesenberg LA. Change in medical students’ attitudes about primary care during the third year of medical school. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):927–929. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199411000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieman LZ, Revicki DA, Baughan DM. The development of an instrument to measure medical students' beliefs about family medicine. Fam Med. 1985;17(6):276–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skootsky AS, Slavin S, Wilkes MS. Attitudes toward managed care and cost containment among primary care trainees at 3 training sites. Am J Manag Care. 1999;5(11):1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ochoa-Diaz Lopez H. Medical curricula and students’ attitudes toward general and family practice in Mexico. Med Educ. 1987;21(3):189–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1987.tb00690.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1987.tb00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sönnichsen AC, Donner-Banzhoff N, Baum E. Motive, Berufsziele und Hoffnungen von Studienanfängern im Fach Medizin. Z Allg Med. 2005;81(5):222–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-836501. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-836501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kromark K, Gedrose B, van den Bussche H, Jünger J, Köhl-Hackert N, Robra B-P, Rothe K, Schmidt A, Stosch C, Alfermann D. Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Medizinische Ausbildung (GMA). Bochum, 23.-25.09.2010. Düsseldorf: German Medical Science GMS Publishing House; 2010. Übergang zwischen PJ und fachärztlicher Weiterbildung: Studienergebnisse einer Befragung am Ende des PJ; p. Doc10gma112. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/10gma112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäfer HM, Sennekamp M, Güthlin C, Krentz H, Gerlach FM. Kann das Blockpraktikum Allgemeinmedizin zum Beruf des Hausarztes motivieren? Z Allg Med. 2009;85(5):206–209. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunker-Schmidt C, Breetholt A, Gesenhues S. Blockpraktikum in der Allgemeinmedizin: 15 Jahre Erfahrung an der Universität Duisburg-Essen. Z Allg Med. 2009;85(4):170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bethune C, Hansen PA, Deacon D, Hurley K, Kirby A, Godwin M. Family medicine as a career option: how students' attitudes changed during medical school. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):881–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmann C, Hölzer H, Dieterich A, Fabry G, Langewitz W, Lauber H, Ortwein H, Pruskil S, Schubert S, Sennekamp M, Simmenroth-Nayda A, Silbernagel W, Scheffer S, Kiessling C. Longitudinales bologna-kompatibles Modell-Curriculum „kommunikative und Soziale Kompetenzen“: Ergebnisse eines interdisziplinären Workshops deutschsprachiger medizinscher Fakultäten. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2009;26(4):Doc38. doi: 10.3205/zma000631. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thistlethwaite J, Kidd MR, Leeder S, Shaw T, Corcoran K. Enhancing the choice of general practice as a career. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(11):964–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmacke N. Das Ansehen der Allgemeinmedizin. Z Allg Med. 2010;86(3):113–115. [Google Scholar]