Abstract

Objective: The Ulm pilot study aimed to explore factors for a successful combination of medical education and starting a family. The empirical data derived from this study constitutes the foundation for an evidence-based reform of the medical curriculum in Ulm.

Methods: In 2009, qualitative interviews with 37 of the 79 medical students with children at University of Ulm were conducted and analyzed using content analysis. The detected problem areas were used to develop a quantitative questionnaire for studying parents and academic teaching members in medical education in Ulm.

Results: The parents were older, more often married and more likely to already have obtained a first training. One third of the students thought there was no ideal time to start a family during the years of medical education or specialist training. However, the majority of the students (61%) were convinced that parenthood is more compatible with medical studies than with specialist training. The interview data suggests that the end of medical school (4th to 6th year of studies), preferably during semester break, is especially suitable for child birth since it allows students to continue their studies without ‘losing time’.

Conclusion: The biography and career of studying parents in medicine have specific characteristics. Universities and teaching hospitals are required to no longer leave the compatibility of family and study responsibilities to the students themselves. Rather, flexible structures need to be implemented that enable students to start a family while continuing their education. This means providing more childcare and greater support regarding academic counselling and career development.

Keywords: Career planning, family research, career-family balance, medical education

Abstract

Zielsetzung: Die Ulmer Studie zur Familienfreundlichkeit des Medizinstudiums ermittelte Faktoren für eine erfolgreiche Kombination von Medizinstudium und Familie. Sie zeigt, inwieweit das Studium als richtiger Zeitpunkt für eine Familiengründung geeignet ist. Die Ergebnisse der Studie dienen als Grundlage einer evidenzbasierten Curriculumreform nach familienfreundlichen Kriterien.

Methodik: Im Jahr 2009 wurde eine qualitative Interviewstudie mit 37 der 79 Medizinstudierende mit Kindern der Universität Ulm durchgeführt und inhaltsanalytisch ausgewertet. Auf Grundlage der festgestellten Problem- und Lösungsfaktoren wurde eine quantitative Fragebogenerhebung durchgeführt, an der 45 studierende Eltern und 53 Lehrende in der Medizin teilnahmen.

Ergebnisse: Studierende Eltern der Ulmer Humanmedizin sind durchschnittlich älter, häufiger verheiratet und haben bereits häufiger als andere Studierende eine Erstausbildung absolviert. Knapp ein Drittel der befragten Studierenden und Lehrenden sehen keinen idealen Zeitpunkt für die Familiengründung im Arztberuf. Allerdings wird die Vereinbarkeit von Familie und Studium mehrheitlich leichter eingeschätzt (61% der befragten Studierenden) als die Vereinbarkeit im Arztberuf, insbesondere während der Facharztausbildung. Die Ulmer Interviewdaten zeigen, dass sich vor allem das Ende des Studiums – idealerweise mit Geburtstermin in den Semesterferien – zur Familiengründung ohne größeren Zeitverlust eignet.

Schlussfolgerung: Sowohl die Lebensbiographien als auch die Ausbildungs- und Berufsprofile von studierenden Eltern weisen Besonderheiten auf. Die Universitäten und Kliniken sind gefordert, Vereinbarkeitsfragen nicht mehr nur der Verantwortung der jungen Nachwuchskräfte in der Medizin zu überlassen, sondern verlässliche Strukturen zu schaffen, die es ermöglichen die Familienphase parallel zur Ausbildungsphase zu beginnen. Hierzu gehören neben dem Ausbau von Kinderbetreuungsmöglichkeiten auch die stärkere Unterstützung der Universitäten im Bereich Studienberatung und Karriereförderung.

Introduction

For well-educated women academics in particular it would appear to be difficult to combine family and job. Thus around a quarter of women academics in West Germany remain childless; considerably more than is the case with women who have not studied [1], [2], [3], [4]. Above all, this also affects the compatibility of family and professional life for both women and men in medicine throughout the whole of their training and professional life. As a result the federal government has now established that the attractiveness of jobs in health care with regard to the compatibility of family and professional life must be improved [5].

A large number of studies show the effects of the responsibilities of a family on the academic career of women in terms of a downturn in their career when it comes to higher positions, and thus the difficulty in achieving a balance between working as a doctor and family life [6]. The family responsibilities of medical students represent a little investigated fringe phenomenon. The quota of parents studying in medicine throughout Germany is approximately 7% [7]. Cujec et al., who dealt with the situation of parents studying medicine in Canada, indicate the need to investigate this specific subject in other regional contexts, too [8].

International comparison shows that the decision to start a family is dependant upon the family image in society, the financial independence of students and upon financial assistance from the government [9].

Ochel tells us that students in Scandinavian countries are already solely responsible for their livelihood during their studies. They receive extensive funding from the state. Students in Southern and Western Europe and in Ireland on the other hand, mostly remain financially dependent upon their parents right up until they finish their studies.

The possibility of combining study with family life in Germany is already the subject of many studies [2], [7], however in this connection there is a lack of focus on the particular nature of medical training. In particular the complex framework conditions of medical studies, which usually take 6 years to complete with their high compulsory proportion of practical training, make it difficult to bring up a child.

The present study bridges the gap between the general literature on parents who study and the necessity of the compatibility of career and family during the whole period of medical training, not only after study has been completed [10].

In view of the topicality of issues relating to family policy in current political debate, the present original study investigates whether medical studies are the right point in time to start a family in the medical profession. The empirical study determines factors for a successful combination of medical studies and family, and moreover serves as a basis for an evidence-based curriculum reform according to family-friendly criteria.

Methodology

In a two stage procedure (qualitative and quantitative), a study carried out at the University of Ulm in the academic year 2008/2009 surveyed the living and study situations of student parents in medicine. Problem-focussed interviews were used as a survey instrument. The guide included the categories “biography and life situation”, “environment and attitudes”, and “course of studies and problems”. The research project was supported by the ethics commission of the university, the aims of the study were explained to the participants and they gave their written agreement before the qualitative interviews were conducted. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and finally paraphrased following the qualitative content analysis of Mayring and grounded theory methodology, and categorised into a three-stage procedure (open, theoretical, and selective coding) using the software ATLAS.ti 5.2 [11], [12].

In the written interview, one questionnaire for students and one for teachers was used. The qualitative data analysis took place using the standard software SPSS Version. 18.

Both the interview guide and the questionnaire underwent a pre-test with student parents from other related study programmes. In order to ensure the quality of the survey, a data and method triangulation was carried out [13], as well as at the same time ensuring a research triangulation through the participation of a number of people (the authors of this article) in data evaluation. The results were also critically re-examined by a selected panel of experts from the University of Ulm and checked for plausibility.

Sample

From the complete random sample of 79 students of medicine at the University of Ulm who were chosen on the basis of exemption from tuition fees (overall 4% of medical students in the academic year 2008/2009), 37 took part in problem-centred interviews and 45 in the survey using questionnaires (overall participation rate of 72%, double participation only counted once). In addition 53 teachers (29% response rate for the 184 faculty teachers questioned) took part in the questionnaire.

The results of the questionnaire survey show that the average age of student parents is 31•4 years, and is thus considerably above the overall average age (24•2 years) of medical students in Ulm. 69% of those asked are women and 31% men. 58% of students are married, 33% live in a non-married partnership and 9%, exclusively women, are single parents. On average there are 1•3 children per student parent. 67% have one child, 22% have two children. 79% of the total of 57 children are under the age of six, with about a third under the age of two, one fifth between two and three and one third between three and six years of age.

Results

The results presented here focus on the right moment for starting a family during medical studies which will be illustrated by summaries from the interviews. Results from other specific topic areas asked about in the questionnaires and concrete structural conclusions will be dealt with separately in following publications.

Clinical part of studies as an ideal time to give birth

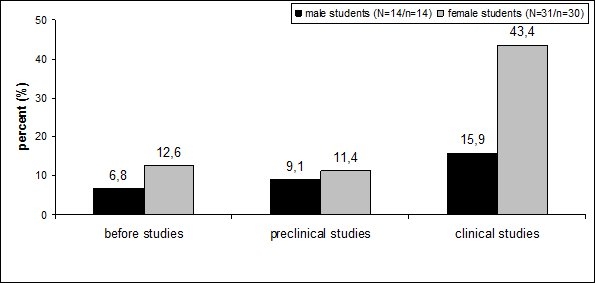

According to the questionnaire, 59% of students questioned have children in the clinical part of their training (see figure 1 (Fig. 1)), with 35% having intentionally planned a child and another 35% not having planned it. A further 30% gave no conclusive answer on their child planning.

Figure 1. Point at which parenthood is entered depending upon gender.

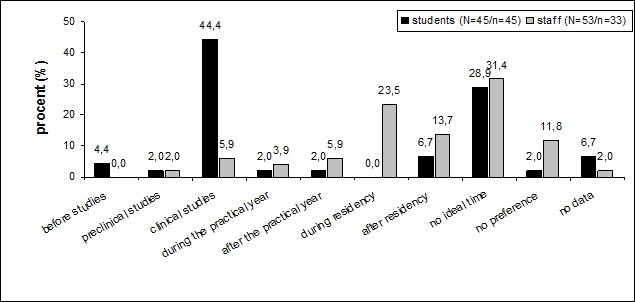

On the evaluation of at what point it is the right time to start a family in the medical profession, the questionnaire indicates a heterogeneous opinion (see figure 2 (Fig. 2)). Approximately one third of students and teaching staff asked see no ideal time for starting a family at present in the medical profession. 44% of students affected would favour the clinical part of their studies, in other words starting a family between the 3rd and the 6th year of study.

Figure 2. The ideal time for starting a family in the medical profession.

37% of teaching staff questioned, on the other hand, would see the period of residency training or later as the ideal time.

The interviews confirm the conscious planning of pregnancy at a well-planned and intended point of time which proved to be ideal for those concerned:

27 year old mother, married, 1 child, 10th semester (lines 22:24): “Yes, the child was properly planned. I mean, I worked out that it would come just at the end of the block semester (8th or 9th semester).”

29 year old mother, married, 1 child, 11th semester (lines 11:38): „…so I just fell pregnant in the block semester (8th or 9th semester) …it actually turned out perfectly.”

Delivery date ideal during the semester break

If the block semester of the 2nd clinical year of study would appear to be the ideal window for starting a family, then the semester break would seem to be the most suitable period for giving birth:

29 year old mother, single, 1 child, 9th semester (lines 14:38): „…well we did a little … I mean we did sort of plan the birth according to the semester break, as far as it can be planned, it could of course all have happed differently. And if the child had arrived in the middle of the semester, I really don’t know whether I would have coped.”

Reasons for this might be that the strain at the end of pregnancy in an ongoing semester would be too great, and the risk of having to break off studies as a result too high. If the modular block semester precedes it, then if there are any problems with pregnancy it is easier to interrupt studies. A later repetition of modules is possible without loss of time. What also speaks in favour of the idea of “delivery date in the semester break” is that following the birth there is a sufficient period for recovery without being compelled to lose study time.

The responsibilities of a family are more compatible with the study of medicine than with working as a doctor

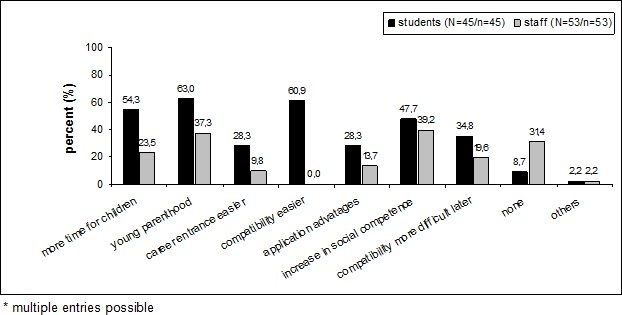

61% of those students questioned see a more easy compatibility with the responsibilities of a family during their studies than when working as a physician (see figure 3 (Fig. 3)). The growth in social competency during studies is also positively assessed.

Figure 3. Advantages of starting a family during studies.

The interviews support the hypothesis that the point of “study” is entirely advantageous, particularly in relation to starting a family later during professional activity.

29 year old mother, married, 1 child, 9th semester (lines 26:31): “[In my studies] I can stay at home if I want and learn and revise by myself. And when I have a job, especially at the beginning I think, when it’s time for children, when you’re still relatively young, it’s more difficult.”

Starting a family during medical studies, the interviews indicate, allows for more simple and flexible time management for studying and childcare. In care emergency situations, time resources are easier and less complicated to arrange, as obligations during study are not as high as in professional life.

28 year old mother, married, 2 children, 9th semester (lines 27:124) “Ok, so when I finish my studies I’ll be 30 and have 2 children. And if I apply for a job somewhere, they can reckon with me not taking time off work in the next 2-3 years because of a child.”

The temporal autonomy and independence during studies also has an advantage compared to that of professional life where in the years spent as an assistant doctor, in particular, a great deal of time is taken up. In this way starting a family during studies might possibly have job application advantages.

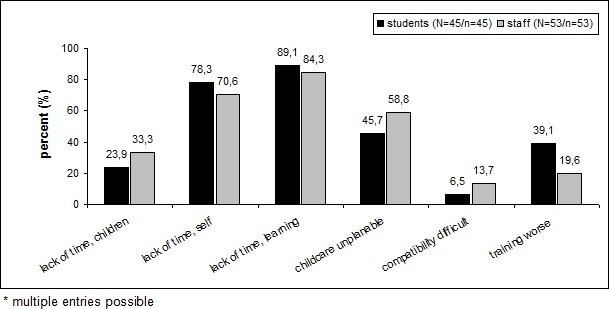

What does prove to be a great disadvantage of parenthood during studies is the lack of time for learning and for oneself (see figure 4 (Fig. 4)). Unplanable childcare also has negative consequences.

Figure 4. Disadvantages of starting a family during studies.

However, the interviews also show that the temporal multiple burden during studies is seen as large, and that there is rather a lack of time for all areas of life.

Discussion

The question as to whether study is the right point for starting a family introduces a number of structural, curricular and social challenges which have to be seen from the point of view of both social science and economics. At the same time training and career must be regarded more strongly as a unit and finally be jointly addressed by health policy and education and family policy. Training of medical students in particular is an integral part of life in the university clinic, and thus unique in comparison to other courses of study. The present study shows peculiarities both in biographies and training and career profiles in the medical profession of studying parents which must be taken into consideration when striving for more family friendliness.

Parents studying medicine: older, married, usually financially secure and with first training

What was characteristic of the medical students interviewed is often their high intrinsic motivation to become doctors, even if the admission requirement (numerus clausus) cannot at first be fulfilled. The career choice of “physician” encourages the use of elaborate roundabout routes until a study place can be allocated ultimately due to other admissions criteria (waiting time, second admissions quota, quota for non-German students, etc.). The waiting period is compensated by training followed by job experience in medical professions. In this way, most student parents in Ulm have already had some first medical training (73%) [14]. Of these 67% have received training in the healthcare service and already have up to three years working experience. Another interpretation of a career change within the healthcare system is that the initial training was decisive in arousing interest in working as a doctor.

Parents studying medicine in Ulm thus exhibit a specific profile in as far as they have an average age of 31•4 years significantly above the average for degree students (7 years difference). For all students in West Germany, Isserstedt describes an age differences of only two years between those with and those without children [15].

The majority of those parents studying are married or live in a non-marital partnership, thus ensuring a stable social and financial environment for starting a family. Married students tend to have an income one and a half times higher than that of unmarried students [16]. If we consider the living situation of parents studying medicine, then we can see that studying with one or more children is not the norm. The life histories of parents studying medicine are usually an exception, as leave the mainstream and start a family, either planned or unplanned, during their training.

Flexible and individual profile of medical training curricula

If medical studies are to be presented in future as an attractive and reasonable point at which to start a family, then measures must be taken at different levels in medical faculties which allow for a flexible and individual course of study, and which counteract the regimentation of medical studies. According to Cujec et al., students with family responsibilities in particular express a great need for flexibility in education [8].

In view of the overall curriculum in the context of family and career planning, the present survey indicates that it would be suitable to first check the family friendliness of the weekly schedules of the clinical training stage, which appears to be a suitable point for starting a family. In particular, modular flexibility of the weekly schedules is required in this respect so that within the core hour period (9am – 4pm) individual course groups are offered at different times of the day, thus making the participation of students with children more easily reconcilable with childcare. In the same way, the day-care times of university childcare institutions must take more consideration of the all-day training structure in medicine, since the study of medicine is exclusively integrated into everyday clinical life and is based upon the shift times of doctors in training. Idle time throughout the day should be avoided, scheduling plans should be dependable and published in good time before the start of each semester (e.g. at the end of previous semester). The interviews made it clear that application procedures must be organised centrally so that no unnecessary organisational effort results. Advice should be systematically tailored to meet student parents’ needs which could be realised, for example, by monitoring study courses [17]. The extension of e-learning offers, particularly as alternatives for theoretical, non-compulsory courses such as lectures, should be promoted.

Parallel phases of education, acquisition and starting a family in the medical profession

The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs’ 7th family report demands a systematic look at the “rush hour” of life, as from the point at which a career and a family are started up to one’s middle years, life becomes increasingly more condensed and alternatives to traditional life plans must to be found [18]. In the medical profession in particular, the long training period (6 years standard period of study and 4-6 years residency) narrows the window of time for starting a family. The timing of starting a family usually follows the life phase model [19]. According to an Allensbach survey in 2005, only 6% of all students in Germany came out in favour of early parenthood, which is a clear indication for the phase model [20]. The number of those who break the phase model and who enter into a parallelisation model, i.e. the simultaneousness of education or employment and family [21], [22], is accordingly comparatively low. What speaks out in favour of the parallelisation model in the medical profession is the easier organisational compatibility of study and family in contrast to the compatibility problems involved in the work-intensive entry into professional life, in particular in the residency phase. The changing conditions in medicine, and the increasingly noticeable scarcity of the “time” resource, demand other life planning models. Life models which are based upon a parallelisation of life phases could then become progressively more part of normality, and in the long term better ensure the compatibility of family and profession.

In view of the promotion of young doctors for medicine, in particular, with a constant increase in the number of women, the lack of opportunities for women in leading positions connected with the existing phase model can also no longer be accepted [6]]. A parallelisation model makes it more easy to penetrate the so-called “glass ceiling”, which is substantially a consequence of the parental leave phases during residency as career-relevant phases. According to this study, having a family during medical studies offers benefits in as far as children can be provided for with childcare, and that by the time their parents start their careers they have grown out of the care-intensive very young age. Employment is then accordingly easier to organise [23]. Furthermore, on entering employment their qualifications correspond to the latest professional developments in medicine, which for the medical profession in particular has great significance in view of ever increasing advancements [24].

Childless Physicians?

When thinking about having children, young doctors are often forced to choose between children or profession. Professional development on the one hand and the desire for a family on the other seem at present to be mutually exclusive. The danger of a career setback is too large and the conflicting relationship between the desire for children and the job is often resolved in favour of the job. Results of the 14th Shell study show that the balance between family and job is, however, the central concept of life for young men and women [25]. According to Kemkes-Grottenthaler, 74•5 % of students want children [26], [27]. A recent 2009 study in North Rhine-Westphalia examined the childless state of academic personnel and came to the conclusion that young academics (78% of women, 72% of men) believe in a fulfilled life with an academic career and a life with children [5]. However, 23% of female academics remain childless [3]. Too long a training period is seen as being jointly responsible for the childlessness of academics. An initially deferred desire for children is thus later no longer realised.

Conclusion: Inferences for Practice

In view of the changing face of the medical profession (lack of doctors, higher proportion of women, trend toward emigration, increasing work load, etc.), structural conditions should be improved for all periods of medical training, so that the desire to start a family can be realised independently of a professional career.

Opportunities should be created to break through the "life phase model" by offering relief, for example through flexible and individualised organisation of curriculum, part time options, childcare or contact and return to study programmes, during studies.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Presidential Council of the University of Ulm, which authorised the funding for this study from tuition fees. Our special thanks go to all those students of medicine in Ulm with children who took part in this study.

Competing interests

The authores declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Schmitt C, Wagner G. Kinderlosigkeit von Akademikerinnen überbewertet. Wochenbericht des Deutschen Instituts für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW) 2006;21:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelißen W, Fox K. Studieren mit Kind. Die Vereinbarkeit von Studium und Elternschaft: Lebenssituationen, Maßnahmen und Handlungsperspektiven. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistisches Bundesamt. Mikrozensus 2008. Neue Daten zur Kinderlosigkeit in Deutschland. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2009. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metz-Göckel S. Wissenschaft als Lebensform - Eltern unerwünscht? Kinderlosigkeit und Beschäftigungsverhältnisse des wissenschaftlichen Personals aller nordrhein-westfälischer Universitäten. Opladen: Budrich; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDU; CSU; FDP. Wachstum. Bildung. Zusammenhalt. Der Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und FDP. Berlin: CDU; 2009. Available from: http://www.cdu.de/doc/pdfc/091026-koalitionsvertrag-cducsu-fdp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ. 2001;35(2):139–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middendorff E. Studieren mit Kind. Ergebnisse der 18. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerks durchgeführt durch HIS. Bonn, Berlin: HIS Hochschul-Informations-System; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cujec B, Oancia T, Bohm C, Johnson D. Career and parenting satisfaction among medical students, residents and physician teachers at a Canadian medical school. Can Med Ass J. 2000;126(5):637–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochel W. Familiengründung trotz Studiums. Ifo schnelldienst. 2006;59:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebhardt H, Fegert JM. Medizinstudium mit Kind: Familienfreundliche Studienorganisation in der medizinischen Ausbildung. Lengerich: Pabst Sciences Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. 10. Auflage. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser BG, Strauss AL, Paul AT. Grounded theory: Strategien qualitativer Forschung. 2. korrigierte Aufl. Bern: Huber; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamnek S. Qualitative Sozialforschung Lehrbuch. 4., vollst. überarb. Aufl. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebhardt H, Fegert JM, Dittrich W, Nürnberger F. Medizin studieren mit Kind. Ein Trend der Zukunft? Dtsch Ärztebl. 2010;34-35:1613–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isserstedt W, Middendorff E, Fabian G, Wolter A. Die wirtschaftliche und soziale Lage der Studierenden in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2006. 18. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerks durchgeführt durch HIS Hochschul-Informations-System; ausgewählte Ergebnisse. Bonn: Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Middendorff E. Kinder geplant? Lebensentwürfe Studierender und ihre Einstellung zum Studium mit Kind. Befunde einer Befragung des HISBUS-Online-Panels im November/Dezember 2002. Hannover: HIS Hochschul-Informations-System GmbH; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebhardt H, Stolz K, Mörtl K, Prospero K, Niehues J, Fegert JM. Evidenzbasierte Beratung und Studienverlaufsmonitoring für studierende Eltern in der Medizin. Z Berat Stud. 2010;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Familie zwischen Flexibilität und Verlässlichkeit. Siebter Familienberich. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Familie, Frauen, Senioren und Jugend; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myrdal A, Klein V, Schroth-Pritzel U. Die Doppelrolle der Frau in Familie und Beruf. 2. Aufl. Köln [u.a.]: Kiepenheuer & Witsch; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach. Einflussfaktoren auf die Geburtenrate. Ergebnisse einer Repräsentativbefragung der 18- bis 44jährigen Bevölkerung. Einflussfaktoren auf die Geburtenrate. Allensbach/Bodensee: Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurscheid C. Das Problem der Vereinbarkeit von Studium und Familie. Eine empirische Studie zur Lebenslage Kölner Studierender. Münster: LIT; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amend-Wegmann C. Vereinbarkeitspolitik in Deutschland: aus der Sicht der Frauenforschung. Hamburg: Kovac; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helfferich C, Hendel-Kramer A, Wehner N. fast - Familiengründung im Studium. Eine Studie in Baden-Württemberg; Abschlußbericht zum Projekt. Stuttgart: Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allmendinger J. Familien auf der Suche nach der gewonnenen Zeit. In: Aus Politik und Zeigeschichte. Parlament. 2005;23-24:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutsche Shell-Aktiengesellschaft Jugendwerk. Jugend 2002 zwischen pragmatischem Idealismus und robustem Materialismus. 4. Aufl. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemkes-Grottenthaler A. Determinanten des Kinderwunsches bei jungen Studierenden: Ein Pilotstudie mit explorativem Charakter. Z Bevölkerungswiss. 2004;29(2):193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirth H, Dümmler K. Der Einfluss der Qualifikation auf die Kinderlosigkeit von Frauen zwischen 1970 und 2001 in Westdeutschland: Analysen mit dem deutschen Mikrozensus. Z Bevölkerungswiss. 2005;30(2/3):313–336. [Google Scholar]