Abstract

Biomarker discovery and proteomics have become synonymous with mass spectrometry in recent years. Although this conflation is an injustice to the many essential biomolecular techniques widely used in biomarker-discovery platforms, it underscores the power and potential of contemporary mass spectrometry. Numerous novel and powerful technologies have been developed around mass spectrometry, proteomics, and biomarker discovery over the past 20 years to globally study complex proteomes (e.g., plasma). However, very few large-scale longitudinal studies have been carried out using these platforms to establish the analytical variability relative to true biological variability. The purpose of this review is not to cover exhaustively the applications of mass spectrometry to biomarker discovery, but rather to discuss the analytical methods and strategies that have been developed for mass spectrometry–based biomarker-discovery platforms and to place them in the context of the many challenges and opportunities yet to be addressed.

Keywords: biological variability, analytical variability, longitudinal sampling

1. INTRODUCTION

The term biomarker has been broadly defined as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” (1, p. 91). These processes encompass physical symptoms such as fever, weight loss, cough, sore throat, and heart arrhythmia and biological factors such as electrolyte concentration and composition (e.g., Na+, K+, and Ca2+), glucose concentration, cholesterol concentration and composition, mutated DNA and RNA, and protein concentration and composition (e.g., Troponin, B-type natriuretic peptide, CA-125, prostate-specific antigen). Analytical instrumentation, including mass spectrometry (MS), has played an increasingly important role during the latter half of the twentieth century in measuring molecular species for clinical diagnosis (2–5). As the molecular specificity and sensitivity of analytical techniques have increased, so too has our awareness of the magnitude of biological complexity and its implications for discovering new molecular biomarkers of disease. This is especially true with regard to protein biomarker discovery in accessible human fluids such as urine and plasma, the latter of which represents one of the most formidable analytical challenges with regard to sample complexity, preparation, variability, and dynamic range (6). The profound changes in MS over the past 20 years have brought new technology platforms and new technologists (e.g., analytical chemists) into the fields of protein biomarker discovery and clinical chemistry. As these distinct yet interrelated fields continue to merge, new analytical techniques are being used to study well-established biological issues in ways that will require more extensive experimental designs and improved collaboration among classically trained chemists, clinical chemists, biotechnologists, statisticians, and health care providers (7–13).

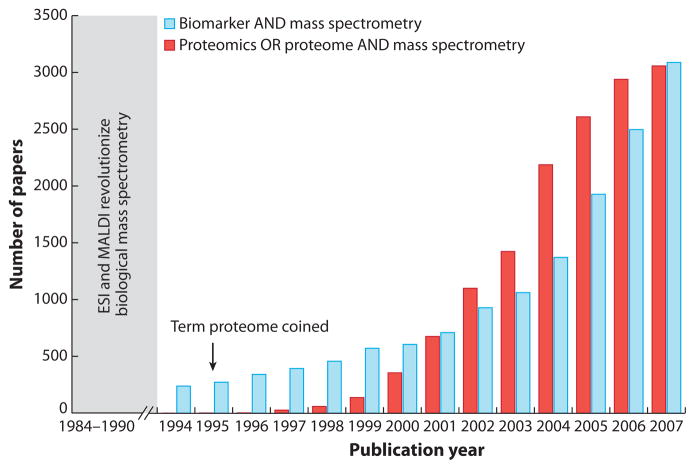

A paradigm shift in protein biomarker–discovery efforts occurred with the introduction of electrospray ionization (ESI) (14) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-MS (15). Until the late 1980s, only ~50 plasma proteins had been identified using a combination of one- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and protein sequencers (6). However, since the completion of the human genome project and the integration of protein-separation techniques with MS (16) just under 20 years ago, the number of unique plasma proteins identified has increased more than tenfold (6). The combination of novel mass spectrometric technologies with the completion of the human genome project spawned the term proteome (17) and the field of proteomics. Proteomics is a broad term based on the concepts described by Anderson and coworkers (18) of the Human Protein Index and is typically defined as the field of study that determines the identities, quantities, structures, and biochemical and cellular functions of all proteins in an organism, organ, or organelle and how these functions vary in space, time, and physiological state. Proteomics involves the study of proteins that are specifically or nonspecifically cleaved, posttranslationally modified (e.g., phosphorylated and glycosylated), and derived from alternatively spliced gene sequences. In the context of protein biomarker discovery, the terms biomarker, proteomics, and MS are often used interchangeably, as shown in Figure 1. The multidisciplinary nature of protein biomarker discovery has created an enormous body of literature, which will continue to expand as bioanalytical technologies are improved and made accessible to increasingly diversified researchers.

Figure 1.

Number of publications as a function of publication year (1994–2007) found through the Web of Science database using the search terms biomarker AND mass spectrometry and proteomics OR proteome AND mass spectrometry. Geometric growth in this field can be clearly attributed to the introduction of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) and electrospray ionization (ESI).

Several recent reviews have described this expanding landscape from both global and disease-specific perspectives. These reviews have discussed cardiovascular disease (19–21), cancer in general (22, 23), breast cancer (24–26), ovarian cancer (27–30), lung cancer (31), and neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) (32, 33). In this review, we do not focus on biomarker discovery as it relates to specific diseases, given the enormousness of the literature (>16,000 papers available through Web of Science 2008, http://apps.isiknowledge.com). Instead, we cover many of the contemporary MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms that are being utilized to differentiate healthy and diseased individuals, then place these analytical approaches and their inherent variabilities in the context of established issues of biological variability. As the novelty of identifying hundreds of plasma proteins by MS fades, and as proteomics researchers come up short in the search for novel protein biomarkers, it becomes important to revisit many of the challenges that have preoccupied researchers for over 100 years (7–13, 34–37).

2. MASS SPECTROMETRY–BASED BIOMARKER-DISCOVERY PLATFORMS

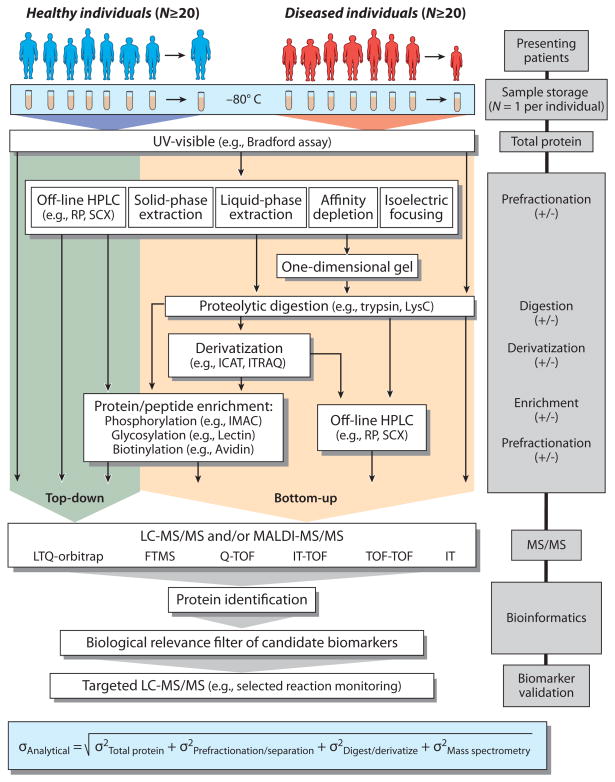

The search for protein biomarkers involves multiple technologies and research disciplines. Figure 2 provides an overview of some common MS-based biomarker-discovery workflows. In general, these workflows involve sample collection, fractionation, mass spectral analysis, data analysis and biological filtering (bioinformatics), and ultimately validation. The samples, including plasma, serum, cerebral spinal fluid, and urine, are collected from a population of presenting individuals defined in varying degrees of detail as either healthy or diseased. Although the workflows shown in Figure 2 are applicable to all of these biological fluids, we restrict our discussion to plasma, given its prominence in biomarker discovery. It is important to note that typically only one sample per individual is collected. Regardless of downstream processing and analysis, the results only reflect a very narrow snapshot of an individual’s proteome over his or her entire lifetime (38). This fact is of critical importance, as is discussed in more detail below.

Figure 2.

Typical workflows for mass spectrometry–based biomarker discovery and validation. Abbreviations: FTMS, Fourier transform mass spectrometry; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; ICAT, isotope-coded affinity tag; IMAC, immobilized metal affinity chromatography; ITRAQ, isotopic tag for relative and absolute quantification; LTQ, linear trap quadrupole; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; RP, reverse-phase liquid chromatography; SCX, strong cation-exchange liquid chromatography; TOF, time of flight.

Once the samples have been procured, they are typically processed to remove abundant proteins, to isolate certain protein classes (according to, e.g., molecular weight, pI, hydrophobicity, posttranslational modifications), or to fractionate the sample into more manageable sizes. Most workflows fall into the “bottom-up” (39–41) category, where the plasma proteins are proteolytically digested into peptides that are more amenable to contemporary separation and MS technologies. The “top-down” (42–44) approach analyzes intact plasma proteins, which is far more challenging due to the difficulty of separating and mass spectrally analyzing intact proteins. Thus, the latter approach has not yet become routine. Although some workflows are more commonly used than others (e.g., bottom-up versus top-down), no single approach has proved to be better than the others, as is evident from the dearth of validated MS-discovered biomarkers.

Following processing, the plasma samples are directed to one or more MS systems for protein identification and relative quantification. Discovery-based proteomics requires instruments that can provide both accurate intact masses and their subsequent fragment masses for confident identification. The proteins that are differentially expressed in the diseased samples versus the healthy samples can then be evaluated on the basis of their relevance to the particular disease. Ultimately, the proteins that fit these criteria are further studied via targeted assays across large numbers of patient samples using either enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or selected reaction monitoring (SRM). This overview is intended to illustrate the importance of analytical chemistry in several aspects of MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms (i.e., from discovery-based global proteomics to target-based validation).

The analytical instrumentation used in these multistep workflows includes ultraviolet–visible absorption (e.g., total protein), fluorescence spectroscopy (e.g., gel imaging), liquid chromatography, and MS. Thus, if the ultimate goal is to identify a protein (or set of proteins) that are up- or downregulated in diseased versus healthy patients, then one must attempt to determine the overall analytical variability of the measurement. Given the multitude of workflows and instruments that are used in biomarker discovery, one can expect the analytical variability to be large (much larger than in single-analyte assays) when considering hundreds of proteins measured from a single sample. The box at the bottom of Figure 2 is a small sampling of individual contributions to analytical variability. As discussed below, estimating analytical variability is important when determining biological variability. MS-based biomarker-discovery workflows, as delineated in Figure 2, have yet to separate these two forms of variability such that true candidate biomarkers can be identified within patient populations.

3. THE INDEX OF INDIVIDUALITY AND GLOBAL PROTEOMICS

3.1. Healthy Versus Diseased

The unqualified use of the terms normal and healthy in describing one set of plasma samples relative to a diseased set of samples is widespread in MS-based protein biomarker–discovery efforts. Samples are generally collected at the point of presentation, and they constitute single time points in each individual’s life (Figure 2). Misuse of the terms normal and healthy can be attributed to many factors including (a) an unawareness of the issues of normality (e.g., index of individuality), (b) a need to define the analytical limits of measuring multiple proteins (>100) at once, and (c) an inability to define a normal plasma proteome by MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms due to a lack of resources such as skilled personnel, sample access, and instrument time (see sidebar, Time-Demands on MS-Based Biomarker-Discovery Efforts).

These points echo many of the issues described by Anderson and colleagues (6, 45) and R.L. Lundblad, who writes: “Somewhat remarkable is that the above studies, including references 49, 53, and 58 [index of individuality], are not cited or considered to a greater extent in the burgeoning literature on clinical proteomics” (12, p. 268). Although it is easy to find fault with many of the approaches used in contemporary biomarker-discovery efforts (our laboratory included), new technologies always involve growing pains as technologists skilled in developing instrumentation are thrust into the realm of biological uncertainty. The limits of these technologies must be explored and defined before meaningfully applying them to large-scale biomarker-discovery efforts. Nonetheless, as the technology matures and as a critical mass of skilled personnel emerges, we should revisit the immense clinical chemistry literature regarding biological normality in the context of contemporary MS and how experimental designs must change.

The variation of biochemical constituents in blood both within and between healthy individuals has been recognized for more than 50 years (46–61). Several books on this topic cover the immense body of literature in great detail (4, 5, 46–49). R.J. Williams was one of the first scientists to discuss in great detail the “need in human biology and medicine for more attention to variability and individuality at the physiological and biochemical levels” (49, p. ix). Subsequent research brought more analytical and statistical rigor to defining biochemically what constitutes a normal or healthy individual.

An important series of papers published in the early 1970s studied the levels of biochemical constituents from 68 normal subjects, whose blood was collected every day for 12 weeks (52–56). The biochemical constituents included Na, Ca, K, Cl, CO2, glucose, total protein, and albumin. By making measurements of longitudinally procured samples over a period where the subjects were assumed to remain in a state of homeostasis, the authors determined intraindividual variability for each of these biochemical constituents. They then compared these intraindividual variabilities to the interindividual variability from the group for each constituent. These studies culminated in the formulation of the index of individuality (see sidebar, Index of Individuality) (58), which is the ratio of intraindividual to interindividual variability (CVW/CVB) that allows one to set cutoff values for the importance of analyte levels in classifying an individual as normal or diseased.

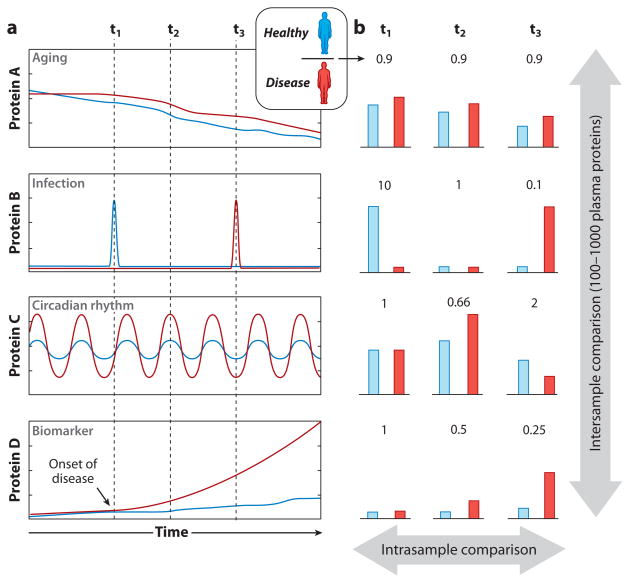

Figure 3a shows the hypothetical levels of four proteins (A, B, C, and D) for both a healthy individual and a diseased individual as a function of time. If we assume that the biological function(s) of the protein is unknown (at least with respect to the disease being studied), any of these proteins could be considered a potential biomarker, depending on the time of sample collection. A typical experiment that employs a workflow from Figure 2 involves collecting plasma from two individuals at a single time point, as illustrated in Figure 3a. Figure 3b illustrates the hypothetical data output (assuming the analytical variability is small or constant) for all four proteins at each of three time points (t1, t2, and t3). Analysis of the data at t1 shows that protein B is downregulated in the diseased individual relative to the healthy individual, suggesting that it may be a potential biomarker. However, if the plasma samples were collected at t2, proteins C and D could be interpreted as potential biomarkers. At time point t3, proteins B and D are upregulated, and protein C is downregulated in the diseased individual relative to the healthy individual.

Figure 3.

(a) Hypothetical changes in the concentration of four different proteins (labeled A through D) in one healthy individual and one diseased individual as a function of time. Each protein is either up- or downregulated in relation to aging (protein A), infection (protein B), circadian rhythm (protein C), and biomarker/onset of disease (protein D). (b) The ratio of the protein concentration of the healthy individual to that of the diseased individual as a function of when the sample was collected. Typical biomarker-discovery experimental designs commonly utilize interindividual comparisons; however, intraindividual comparisons should also be an integral part of biomarker-discovery experimental designs.

The scenarios described above clearly underscore the inherent variability of plasma proteins that occurs in both healthy and diseased individuals. However, much of this variability is unrelated to the disease being studied. This becomes increasingly acute when one considers that contemporary MS-based biomarker-discovery workflows can identify between 100 and 1000 plasma proteins. The likelihood that 100 proteins for a given individual at any time point fall within a 95% reference range is less than 1% (0.95100 × 100%), and for 1000 proteins, the likelihood is less than 1 × 10−20%. One can increase the number of patients studied such that outlier protein levels can be statistically tested and removed from consideration. However, this would not address the issue of intraindividual variability for a particular protein (even proteins that bioinformatically do not register with a given disease), which in some disease states could be extremely valuable. If the intraindividual variation is very small for a given protein in an individual, an increase or decrease of that protein outside of the intraindividual variation yet still inside of interindividual variation may prove significant. In MS-based biomarker discovery, we often assume that we can accurately measure the plasma proteome for individuals in a given state, when in fact we cannot even quantify the analytical and intraindividual variability contributing to the protein levels we are measuring. Establishing these fundamental figures of merit for a given workflow (Figure 2) should be a priority in biomarker-discovery efforts so that MS-based platforms can attain the analytic robustness necessary for identifying clinical biomarkers.

3.2. Toward a Global Proteome Index of Individuality

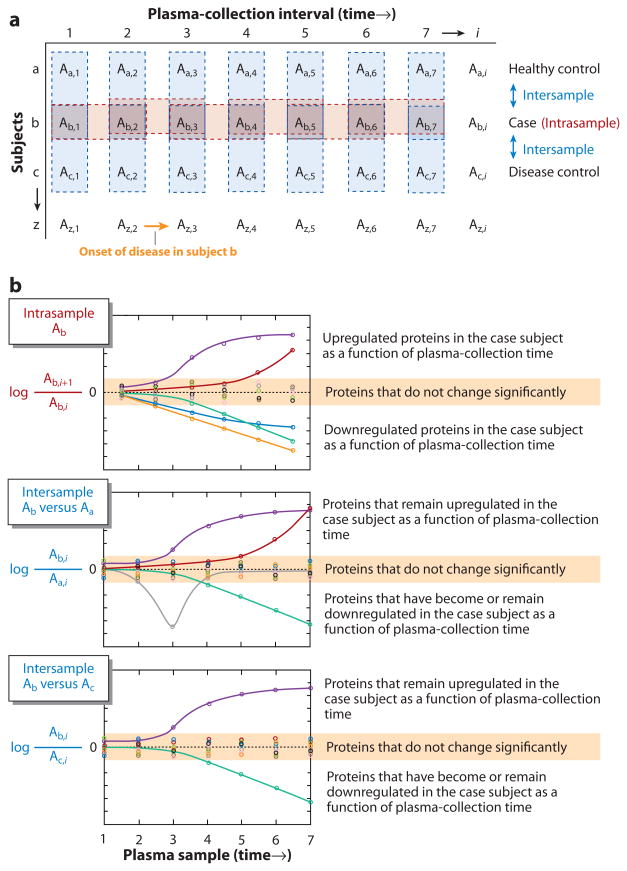

Levels of biochemical constituents, including proteins, can fluctuate dramatically within individuals regardless of their state of health. Factors that can impact fluctuations in blood constituents include posture, stress, diet, exercise, circadian rhythm, menstrual cycle, drug use, ambient temperature, and altitude (5, 46). Posture, for example, can increase or decrease the total volume of blood in the body by as much as 10% (62). There is a genuine need to procure longitudinal samples from subjects to establish the analytical and global proteome intraindividual variability for contemporary MS-based proteomics platforms. This would provide a means to calculate, using quantitative MS methods, a global proteome index of individuality (GPII). Figure 4 shows a hypothetical longitudinal experiment in which plasma is collected from multiple subjects over several time points. We believe that longitudinal studies that include diseased patients, disease controls, and healthy controls from well-defined biospecimen-collection protocols, along with technical replicates, will be critical to making global biomarker discovery a highly fruitful endeavor.

Figure 4.

Hypothetical data illustrating the power of longitudinal studies with both intra- and interindividual comparisons. (a) The blue shaded boxes represent the intersample-comparison plasma sets, and the red boxes represent the intrasample-comparison plasma sets. Subject a is the healthy control, subject b is the “case” (i.e., has the disease of interest), and subject c is the disease control (i.e., has a disease other than the one of interest). (b) In the first plot (top), the ratios of the ith +1 to the ith protein levels (Ab, i + 1/Ab,i ) for subject b are plotted as a function of sample-collection time points. The data show two upregulated proteins (upper trendlines) and three downregulated proteins (lower trendlines) relative to five proteins (center; no trendlines) that do not change significantly (highlighted in orange). Thus, there are five candidate markers for the case. (Center plot) The ratios of protein levels between subject b and a healthy patient (subject a) plotted as a function of sample-collection time points. The same two proteins remain upregulated, but two of the previously downregulated proteins cancel one another, thus falling into the insignificant region (highlighted in orange). One protein spikes downward during the time range of the study, suggesting a temporary environmental condition (e.g., infection, stress, diet, etc.). There are now three candidate biomarkers. (Bottom plot) The ratios of protein levels between subjects b and c plotted as a function of sample-collection time points. One of the upregulated proteins cancels, and the spike protein also cancels. There are now only two protein biomarker candidates that appear to track the onset and progression of the disease of interest.

4. SUMMARY

Analytical chemists continue to work with clinical chemists, biotechnologists, clinicians, and statisticians to identify predictive biomarkers for diseases of all types. The past 10 to 15 years of MS-based biomarker-discovery efforts have witnessed the development of robust technologies that have allowed researchers to measure hundreds of plasma proteins per patient sample. However, scientists have neglected to develop experimental designs that would allow for the determination of baseline parameters such as analytical, intraindividual, and interindividual variability of these hundreds of proteins in the context of MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms. As a consequence, the proteomics community has been unable to determine what constitutes normal versus disease-specific regulation of these hundreds of proteins. Current technology will allow us to engage in research on defining a GPII, which in turn should serve the scientific community for years to come in biomarker-discovery research. Williams stated more than five decades ago (49, p. 6) that “[t]he development of the area of biochemical individuality is made urgent by the foregoing considerations. It is made possible because of the introduction of new techniques and tools. Many of the facts related to biochemical individuality which are present in the later chapters of this book could not have been brought to light if it were not for some of the newer tools: chromatography, isotopic techniques, and physical methods of analysis and separation. The collection of data in the area of individuality is in its infancy, and newer techniques will make possible the collection of vastly more pertinent and satisfactory information than is available at present. Many of the data which are now available have been collected by investigators who appear to have no particular interest in variation as such or concern with its possible significance.”

TIME DEMANDS ON MS-BASED BIOMARKER-DISCOVERY EFFORTS.

For a study involving 100 individuals (50 healthy and 50 diseased):

Plasma-collection time is 1 to 3 years, depending on disease prevalence.

Plasma fractionation (pre-MS) takes longer than 1 month.

LC-MS/MS analysis time (90 min) per plasma sample (assuming 10 fractions per plasma sample) with three technical replicates is 45 h.

Total LC-MS/MS time for 100 samples with three technical replicates is 187.5 days, or approximately half a year (45 h × 100 individuals = 187.5 days).

Total LC-MS/MS time for five time points from 100 individuals with three technical replicates is 937.5 days, or roughly 2.5 years.

The time required for protein identification and bioinformatics is unlimited.

INDEX OF INDIVIDUALITY.

The importance of the intraindividual and interindividual variability of biological analytes has long been appreciated in the field of clinical chemistry. In 1974, Eugene K. Harris (58) defined the index of individuality as

where CVA, CVw, and CVB are the analytical, within-subject (intraindividual), and between-subject (interindividual) coefficients of variation, respectively. In some cases, CVA ≪ CVW and is therefore omitted. The magnitude of CVA versus CVW for a given protein measured by MS from multiple samples collected over a period of time is unknown.

SUMMARY POINTS.

MS has revolutionized biomarker discovery with its ability to globally identify and comparatively quantify proteins from accessible complex mixtures such as plasma.

The multitude of MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms has made differentiating analytical from biological variability between laboratories very difficult, if not impossible.

Quantitative MS strategies including label and label-free methods for comparative proteomic investigations of plasma are still in their infancy, but they offer great promise and opportunity for further advances.

More detailed annotated protein databases that include alternative splicing, point mutations, and polymorphisms are needed to improve the effectiveness of MS to globally identify biomarkers.

Careful use and systematic development of prefractionation methods for plasma have been and will continue to be essential for MS-based biomarker-discovery efforts.

The significant variability of analytes in healthy individuals, observed both within and between subjects, has been acknowledged for more than 50 years, yet contemporary MS-based biomarker-discovery efforts have largely failed to address this critical issue in experimental designs.

Longitudinal comparative studies of statistically significant numbers of humans or animals performed using MS-based proteomics technology will be critical in defining the relationship among analytical, within-subject, and between-subject variability in the context of global proteomics technology (i.e., the GPII).

FUTURE ISSUES.

It is necessary to perform a comprehensive assessment of the analytical figures of merit and implications in biomarker discovery for multiple MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms.

We must address the chromatographic issue of sample-to-sample carry over of peptides and proteins.

Synthesizing stable isotope–labeled internal standards at the protein level with site- and structure-specific posttranslational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) will be critical for quantitative SRM/multiple reaction monitoring analysis and validation.

Acknowledgments

A.M.H. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant number K25CA128666). D.C.M. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant number R33CA105295) and the W.M. Keck Foundation.

Glossary

- Biomarker

a quantifiable characteristic associated with an expressed trait such as a normal biological state, a pathological process, or a pharmacological response to disease treatment

- MS

mass spectrometry

- Plasma

55% v/v liquid component of blood. Differs from serum in that clotting is arrested by the addition of an anticoagulant

- MS-based biomarker-discovery platforms

a complement of bioanalytical technologies (e.g., gel electrophoresis, liquid chromatography, chemical derivatization, and bioinformatics) that are adapted and directed toward plasma protein identification and quantification by MS

- Analytical variability

the total variance (sum of the variances associated with each analytical technique) of a measurement

- Index of individuality

the ratio of the intraindividual coefficient of variation for an analyte (including the analytical coefficient of variation) to the interindividual concentration coefficient of variation for an analyte

- Intraindividual biological variability

the variance (square of the standard deviation) of a specific constituent that is measured over a period of time in the same person

- Interindividual biological variability

the variance of a specific constituent that is measured in a defined population

- GPII

global proteome index of individuality

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Adam M. Hawkridge, Email: adam_hawkridge@ncsu.edu.

David C. Muddiman, Email: david_muddiman@ncsu.edu.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Atkinson AJ, Colburn WA, DeGruttola VG, Demets DL, Downing GJ, et al. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elin RJ. Instrumentation in clinical chemistry. Science. 1980;210:286–89. doi: 10.1126/science.7423189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chace DH. Mass spectrometry in the clinical laboratory. Chem Rev. 2001;101:445–77. doi: 10.1021/cr990077+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 21 Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p. 1450. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, editors. Tietz Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry. 4 W.B. Saunders; 1996. p. 881. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson NL, Anderson NG. The human plasma proteome—history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:845–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.r200007-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ransohoff DF. Opinion—bias as a threat to the validity of cancer molecular-marker research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:142–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Master SR. Diagnostic proteomics: back to basics? Clin Chem. 2005;51:1333–34. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Check E. Proteomics and cancer—running before we can walk? Nature. 2004;429:496–97. doi: 10.1038/429496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamandis EP. Mass spectrometry as a diagnostic and a cancer biomarker discovery tool: opportunities and potential limitations. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:367–78. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hortin GL. Can mass spectrometric protein profiling meet desired standards of clinical laboratory practice? Clin Chem. 2005;51:3–5. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.043281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundblad RL. The Evolution from Protein Chemistry to Proteomics: Basic Science to Clinical Application. Boca Raton: CRC; 2006. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ransohoff DF. Opinion—rules of evidence for cancer molecular-marker discovery and validation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:309–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Electrospray ionization for mass-spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2675315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karas M, Hillenkamp F. Laser desorption ionization of proteins with molecular masses exceeding 10,000 daltons. Anal Chem. 1988;60:2299–301. doi: 10.1021/ac00171a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomer KB. Separations combined with mass spectrometry. Chem Rev. 2001;101:297–328. doi: 10.1021/cr990091m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasinger VC, Cordwell SJ, Cerpa-Poljak A, Yan JX, Gooley AA, et al. Progress with gene-product mapping of the mollicutes—Mycoplasma genitalium. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:1090–94. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501601185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor J, Anderson NL, Scandora AE, Jr, Willard KE, Anderson NG. Design and implementation of a prototype Human Protein Index. Clin Chem. 1982;28:861–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson L. Candidate-based proteomics in the search for biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2005;563:23–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maisel AS, Bhalla V, Braunwald E. Cardiac biomarkers: a contemporary status report. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:24–34. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berhane BT, Zong CG, Liem DA, et al. Cardiovascular-related proteins identified in human plasma by the HUPO Plasma Proteome Project pilot phase. Proteomics. 2005;5:3520–30. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Proteomic applications for the early detection of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:267–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keesee SK. Molecular diagnostics: impact upon cancer detection. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2002;2:91–92. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hondermarck H. Breast cancer: when proteomics challenges biological complexity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:281–91. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R300003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hondermarck H, Vercoutter-Edouart AS, Révillion F, Lemoine J, el-Yazidi-Belkoura I, et al. Proteomics of breast cancer for marker discovery and signal pathway profiling. Proteomics. 2001;1:1216–32. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200110)1:10<1216::AID-PROT1216>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wulfkuhle JD, McLean KC, Paweletz CP, Sgroi DC, Trock BJ, et al. New approaches to proteomic analysis of breast cancer. Proteomics. 2001;1:1205–15. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200110)1:10<1205::AID-PROT1205>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ardekani AM, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF., 3rd Clinical potential of proteomics in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2002;2:312–20. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CJ, Ariztia EV, Fishman DA. Conventional and proteomic technologies for the detection of early stage malignancies: markers for ovarian cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2007;44:87–114. doi: 10.1080/10408360600778885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posadas EM, Davidson B, Kohn EC. Proteomics and ovarian cancer: implications for diagnosis and treatment: a critical review of the recent literature. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:478–84. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams TI, Toups KL, Saggese DA, Kalli KR, Cliby WA, Muddiman DC. Epithelial ovarian cancer: disease etiology, treatment, detection, and investigational gene, metabolite, and protein biomarkers. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2936–62. doi: 10.1021/pr070041v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valle RP, Chavany C, Zhukov TA, Jendoubi M. New approaches for biomarker discovery in lung cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2003;3:55–67. doi: 10.1586/14737159.3.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidsson P, Sjogren M. The use of proteomics in biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases. Dis Markers. 2005;21:81–92. doi: 10.1155/2005/848676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunckley T, Coon KD, Stephan DA. Discovery and development of biomarkers of neurological disease. Drug Dis Today. 2005;10:326–34. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hortin GL, Jortani SA, Ritchie JC, Valdes R, Jr, Chan DW. Proteomics: a new diagnostic frontier. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1218–22. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobs IJ, Menon U. Progress and challenges in screening for early detection of ovarian cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:355–66. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400006-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molloy MP, Brzezinski EE, Hang JQ, McDowell MT, VanBogelen RA. Overcoming technical variation and biological variation in quantitative proteomics. Proteomics. 2003;3:1912–19. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semmes OJ. The “omics” haystack: defining sources of sample bias in expression profiling. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1571–72. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.053405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muddiman DC. “Lewis and Clark” proteomics. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:221–22. doi: 10.1021/pr0626886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Czernik AJ, Yungwirth T, Aebersold R, Chait BT. Matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometric peptide mapping of proteins separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis: determination of phosphorylation in synapsin I. Protein Sci. 1994;3:677–86. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilm M, Shevchenko A, Houthaeve T, Breit S, Schweigerer L, et al. Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature. 1996;379:466–69. doi: 10.1038/379466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–47. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Smith RD. Primary sequence information from intact proteins by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Science. 1990;248:201–4. doi: 10.1126/science.2326633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry KD, Williams ER, Wang BH, McLafferty FW, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Fourier-transform mass spectrometry of large molecules by electrospray ionization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9075–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelleher NL. Top-down proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:197–203A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitzthum F, Behrens F, Anderson NL, Shaw JH. Proteomics: from basic research to diagnostic application. A review of requirements and needs. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:1086–97. doi: 10.1021/pr050080b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson RW. Handbook of Nonpathologic Variations in Human Blood Constituents. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1994. p. 343. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin HF, Guzinowicz BJ, Fanger H. Normal Values in Clinical Chemistry: A Guide to Statistical Analysis of Laboratory Data. Vol. 1. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1975. p. 503. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris EK, Boyd JC. Statistical Bases of Reference Values in Laboratory Medicine. Vol. 146. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams RJ. Biochemical Individuality: The Basis for the Genetotrophic Concept. New York: Wiley; 1956. p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider AJ. Some thoughts on normal, or standard, values in clinical medicine. Pediatrics. 1960;26:973–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keating FR, Jones JD, Elveback LR, Randall RV. Relation of age and sex to distribution of values in healthy adults of serum calcium, inorganic phosphorus, magnesium, alkaline phosphatase, total proteins, albumin and blood urea. J Lab Clin Med. 1969;73:825–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cotlove E, Harris EK, Williams GZ. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects. 3 Physiological and medical implications. Clin Chem. 1970;16:1028–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris EK, Kanofsky P, Shakarji G, Cotlove E. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects.2 Estimating biological components of variation. Clin Chem. 1970;16:1022–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams GZ, Young DS, Stein MR, Cotlove E. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects. 1 Objectives, subject selection, laboratory procedures, and estimation of analytic deviation. Clin Chem. 1970;16:1016–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris EK, Demets DL. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects. 5 Estimated biological variations in ionized calcium. Clin Chem. 1971;17:983–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young DS, Harris EK, Cotlove E. Biological and analytic components of variation in long-term studies of serum constituents in normal subjects. 4 Results of a study design to eliminate long-term analytic deviations. Clin Chem. 1971;17:403–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris EK, Demets DL. Effects of intra-individual and inter-individual variation on distributions of single measurements. Clin Chem. 1972;18:244–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris EK. Effects of intraindividual and interindividual variation on appropriate use of normal ranges. Clin Chem. 1974;20:1535–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harris EK. Some theory of reference values. 1 Stratified (categorized) normal ranges and a method for following an individual’s clinical laboratory values. Clin Chem. 1975;21:1457–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris EK. Some theory of reference values. 2 Comparison of some statistical models of intraindividual variation in blood constituents. Clin Chem. 1976;22:1343–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris EK, Cooil BK, Shakarji G, Williams GZ. On the use of statistical models of within-person variation in long-term studies of healthy individuals. Clin Chem. 1980;26:383–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fawcett JK, Wynn V. Effects of posture on plasma volume and some blood constituents. J Clin Pathol. 1960;13:304–10. doi: 10.1136/jcp.13.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]