The widespread adoption of electronic health records within the oncology community is creating rich databases that contain details of the cancer care continuum. Large portions of this information are locked up in free text, but several efforts are underway to address this.

Abstract

Purpose:

The widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) is creating rich databases documenting the cancer patient's care continuum. However, much of this data, especially narrative “oncologic histories,” are “locked” within free text (unstructured) portions of notes. Nationwide incentives, ranging from certification (Quality Oncology Practice Initiative) to monetary reimbursement (the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act), increasingly require the translation of these histories into treatment summaries for patient use and into tools to assist in transitions of care. Unfortunately, formulation of treatment summaries from these data is difficult and time-consuming. The rapidly developing field of automated natural language processing may offer a solution to this communication problem.

Methods:

We surveyed a cross section of providers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center regarding the importance of treatment summaries and whether these were being formulated on a regular basis. We also developed a program for the Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside challenge, which was designed to extract meaningful information from EHRs. The program was then applied to a sample of narrative oncologic histories.

Results:

The majority of providers (86%) felt that treatment summaries were important, but only 11% actually implemented them. The most common obstacles identified were lack of time and lack of EHR tools. We demonstrated that relevant medical concepts can be automatically extracted from oncologic histories with reasonable accuracy and precision.

Conclusion:

Natural language processing technology offers a promising method for structuring a free-text oncologic history into a compact treatment summary, creating a robust and accurate means of communication between providers and between provider and patient.

Introduction

The treatment of cancer is a multidisciplinary undertaking that typically involves a large team of providers who represent disparate clinical and associated disciplines. Team coordination is often through documentation and, specifically, through the textual entity commonly entitled the “oncologic history.” This portion of a clinical progress note usually summarizes key elements of symptoms leading to a cancer diagnosis, initial treatments, responses to such treatments, and so on. The oncologic history evolves over time and is usually recapitulated in many subsequent progress notes. Unlike heavily structured portions of progress notes, such as medication lists, the oncologic history tends to be an unstructured element that is highly individualized. These entries are almost always in narrative format, which allows providers to freely express thoughts via dictation or free text without the onus of negotiating with an awkward or distracting structured entry system. However, such freedom of expression creates pragmatic issues with respect to the effective and accurate communication of information between providers. Ideally, an oncologic history as a stand-alone document would function as a treatment summary by including details of the cancer stage at presentation, the treatments used, the toxicities of such treatments, and the response to treatment. In reality, a narrative history can lead to problems of comprehension between providers (resulting from grammatical idiosyncrasies and the use of jargon); of accuracy as the oncologic history/treatment summary evolves over time; of transmissibility between institutions that do not have electronic health record (EHR) intercompatibility; and of comprehension between provider and patient (resulting from the use of technical language).

There is a clear need for a robust and consistent communication method between providers and between provider and patient. As we enter the era of ubiquitous EHRs, the challenge of extracting relevant data from large databases will replace the challenge of data paucity that has been faced by earlier generations. Several national efforts underway at the society, certification, and policy levels have direct relevance to this problem of effective communication. We examine each briefly.

Society: Chemotherapy Treatment Summaries

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) considers a treatment summary (a patient-oriented version of the oncologic history) highly important.1 Although this is laudable, it is difficult for busy clinicians to develop de novo summaries, especially when much of the relevant information is contained within unstructured text or must be recalled. There are several detailed templates available through ASCO's Web site (http://www.asco.org/treatmentsummary); for the most part, these must be filled out manually.

Certification: The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative

The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI), under the auspices of ASCO, is a voluntary quality improvement program that can ultimately lead to QOPI certification.2 As of January 2011, 55 practices were QOPI certified. Although this certification carries no legal or reimbursement implications, it is believed to indicate high quality care. To be considered for certification, a practice must collectively review patient charts and determine whether certain measures are documented.

Of 25 core measures, no fewer than four specifically address the need for accurate oncologic histories/treatment summaries. In the most recently published iteration of QOPI certification,3 these measures were not used directly in the scoring process, but they are expected to be included eventually. These measures are: chemotherapy treatment summary completed within three months of chemotherapy end; summary provided to patient within three months of chemotherapy end; summary provided or communicated to practitioner(s) within three months of chemotherapy end; and summary process completed within 3 months of chemotherapy end.

Policy: The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act

One of the primary themes behind the nationwide adoption of EHRs is that conversion from a paper to electronic format should not be done solely as a means of data warehousing. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH),4 which took effect in January 2011, authorizes incentive payments for EHRs that are used in a way that meets specific objectives. These have come to be known as the “meaningful use” criteria. These were formulated by the US Department of Health and Human Services and then revised after more than 2,000 comments were submitted. The final regulation was issued on July 28, 2010.

To qualify for the incentives associated with HITECH, eligible professionals and/or eligible hospitals must meet a set of core objectives and an additional objective from a “menu set.” One core objective and one of the menu items have direct relevance to the problem at hand; both fall under the “policy priority” of improved care coordination. The core objective is the “capability to exchange key clinical information . . . among providers of care and patient authorized entities electronically.”4(p44632) The menu item is the eligible professional or eligible hospital “who transitions their patient to another setting of care or provider of care or refers their patient to another provider of care should provide summary of care record for each transition of care or referral.”4(p44632)

Challenges of Implementation

We must meet and exceed these recommendations and requirements for accurate and complete oncologic histories/treatment summaries if we are to provide quality care for patients. One possible approach to the problem of maintaining a useable and accurate oncologic history (which can more easily be adapted into a treatment summary) is to use natural language processing (NLP) to interpret free text.

NLP is a subdiscipline of computer science that is dedicated to the analysis of unstructured natural language text and speech. Although true understanding of natural language by computers remains an elusive goal, there have been great advances recently in the application of automated methods to extract structured information from unstructured text.5 Medically relevant examples include adverse event detection in discharge summaries,6 disease case discovery in radiology notes,7 and colonoscopy test status detection from EHRs.8 Such applications require that key concepts in the text (such as symptoms, treatments, and tests) be identified and classified, that assertions regarding those concepts (such as presence or absence of a symptom) be detected, and that relationships among concepts (such as temporal or causal) be recognized.

Given that the time and effort spent constructing chemotherapy treatment summaries are known to be large disincentives, we believe that this may be an appropriate application for an NLP-assisted approach. Behind the scenes, such an application would need to scan the EHR to identify progress notes, text sections, and sentences relevant to cancer and related treatment; extract relevant concepts, dates, temporal extents, key relations, and assertions; distinguish between new information and restatements of old information; and organize the findings into a structured summary template, with links to the source sections/sentences that provide evidence for each finding.

Given the breadth of medical vocabulary and the variety of ways of expressing assertions and relationships, automating the extraction of medical information from EHRs is no mean feat. Until recently, even narrowly focused systems required the manual construction of hundreds of specialized linguistic rules.9 However, statistical machine learning techniques are beginning to show promise as an alternative methodology to manual rule construction. In a machine learning approach, a large set of sample medical records is annotated with labels reflecting the concepts to be extracted. These documents serve as a “training set” for an automated learning algorithm, which uses features of the text associated with the training examples to learn classification rules automatically. The accuracy of such a system can be evaluated by measuring its performance on a separate set of annotated test data.

Methods

An electronic survey of the faculty and clinical fellows of the Division of Hematology and Oncology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) was conducted to evaluate attitudes toward the need for treatment summaries and the degree to which treatment summaries have been implemented. This survey consisted of several yes/no questions and scales of importance using standard Likert scale methodology.10

We also conducted a feasibility study to investigate the degree to which an automated concept identification and classification model might transfer to the analysis of concepts within a sample oncologic history. An NLP algorithm was developed by using annotated discharge summaries provided by the Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside Challenge.11 These hospital discharge summaries came from several institutions and were not specific to oncologic diseases. The algorithm was then applied to the portion of an oncologic medical record that was manually identified as the oncologic history. The system identified concepts as belonging to one of three categories: 1) problems; 2) tests; and 3) treatments. These results were compared with those extracted by a human annotator.

Partially identified phrases were considered correct (true positives). Phrases that were correctly identified but assigned to an incorrect category (eg, a problem was identified as a test) were considered false positives. Five candidate oncologic histories were evaluated from a cohort of deceased patients at BIDMC, and overall precision and recall were determined for each. Precision is defined as the number of true positives divided by the number of all positives, and recall is defined as the number of true positives divided by the number of all concepts, as determined by the human annotator. Institutional review board approval was granted at both participating institutions.

Results

There were 28 respondents to the survey—approximately 50% of the faculty and clinical fellows in the Division of Hematology and Oncology at BIDMC. Only three of 28 responding providers (11%) reported that they consistently provided treatment summaries at the conclusion of a course of treatment. However, the majority of respondents felt that summaries were important (86%; average score on Likert scale, 3.96 [0 = “not important”; 3 = “somewhat important”; 5 = “very important”]). Various barriers to implementation were identified, including lack of time, lack of awareness of the initiatives described, and lack of a tool within the EHR to create treatment summaries. The majority of respondents reported that they would always create treatment summaries if an assistive EHR tool were available (54%; average score on Likert scale, 4.18 [0 = “never”; 3 = “sometimes”; 5 = “always”]).

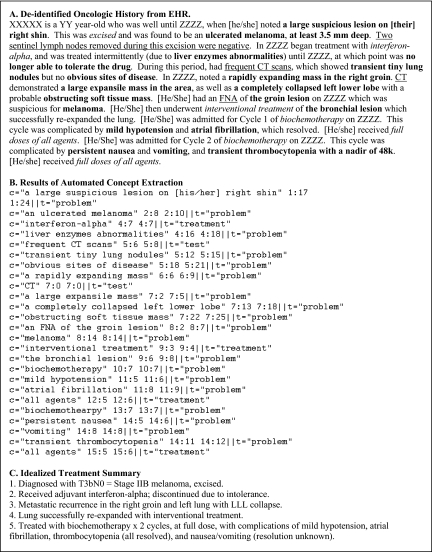

Figure 1 provides an example of one of the oncologic histories, along with the actual output of the NLP system. An idealized treatment summary using this oncologic history text is also shown. Sixteen of 18 problems were correctly identified (three of these were partial identifications); two of four tests were correctly identified; and four of seven treatments were correctly identified. Table 1 shows the results for the five oncologic histories. The mean overall precision for the five cases was 93% (standard deviation, 6%). The mean overall recall was 72% (standard deviation, 8%). All false positives were instances of incorrect categorization.

Figure 1.

Example of data extraction. (A) The actual de-identified text from a progress note, representing the writer's oncologic treatment history. The text has been annotated: bold phrases are problems, italicized phrases are treatments, and underlined phrases are tests. (B) Natural language processing output. Phrases were identified and assigned concept type (problem/treatment/test). Overall precision for this case was 88%, and overall recall was 76%. Three problems that were partially identified were scored as positive identifications. (C) A manually constructed example of a possible reformulation of the text from (A) into a structured element sufficient for succinct communication between providers. EHR, electronic health record; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine needle aspiration.

Table 1.

Precision and Recall of Concept Extraction From Five Oncologic Histories

| Extracted Concept | Physician Annotation | True Positive* (No.) | True Positive (partial;† No.) | False Positive (No.) | False Negative (No.) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncologic history 1‡ | |||||||

| Problem | 18 | 13 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 84 | 89 |

| Test | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 50 |

| Treatment | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 57 |

| Overall | 29 | 19 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 88 | 76 |

| Oncologic history 2 | |||||||

| Problem | 27 | 18 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 80 | 74 |

| Test | 9 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 56 |

| Treatment | 14 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 89 | 57 |

| Overall | 50 | 29 | 4 | 6 | 13 | 85 | 66 |

| Oncologic history 3 | |||||||

| Problem | 14 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 79 |

| Test | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Treatment | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 75 |

| Overall | 27 | 18 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 81 |

| Oncologic history 4 | |||||||

| Problem | 9 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 89 |

| Test | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 50 |

| Treatment | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 50 |

| Overall | 13 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 77 |

| Oncologic history 5 | |||||||

| Problem | 21 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 62 |

| Test | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 75 | 50 |

| Treatment | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 50 |

| Overall | 29 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 94 | 59 |

Full true positive was defined as a fully identified concept.

Partial true positive was defined as a partially identified concept.

Case history 1 is shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

The widespread adoption of EHRs within the oncology community is creating rich databases that contain details of the cancer care continuum. Large portions of this information are locked up in free text, and several efforts are underway to address this. ASCO encourages the deliberate unlocking of this information by the manual creation of a chemotherapy treatment summary. QOPI is a quality assurance tool that provides certification to oncology practices that verify that pertinent information is contained within the record. HITECH offers financial incentives for practices and individual physicians that use EHRs to achieve “meaningful use.” The universal presence of a robust, accurate oncologic history/treatment summary could lead to easy and practical physician buy-in to these three programs. Our survey clearly demonstrated that, despite the existence of these incentives, few practitioners at BIDMC are currently developing treatment summaries. Although these results are not necessarily generalizable to other institutions, the barriers of time constraints and a lack of technological infrastructure are likely to be shared by most practicing oncologists.

We have demonstrated that it is possible to extract concepts from an unstructured oncologic history with reasonable accuracy and precision. Given that the model was trained by using clinical records that were largely from other institutions and that the set contained few oncologic records, this degree of transfer is promising and would be expected to improve with additional training on more relevant medical records. Although anything short of 100% accuracy might not be sufficient for a fully automated application, this level of performance may be more than adequate for computer-assisted solutions to tasks that are currently time-consuming or tedious to perform by hand.

For example, once a natural language processing system constructs a candidate summary, it could be presented to a clinician for review. The clinician would then verify that the summary information presented is accurate and complete. To assist in verifying accuracy, the system could allow a clinician to choose any fact in the summary and see the primary textual evidence (sentences/sections of the patient record) that support it. Manual corrections could then be entered by the clinician. To assist in verifying completeness, the system should make it easy to examine text in the neighborhood of specified concepts or assertions. This would allow a clinician to hone in, for example, on sections that mention a drug or condition whose relevance the automated system may have missed.

Our feasibility study was not designed to evaluate assertions and relationships between concepts. Future work will focus on improving the precision and recall performance of concept extraction, as well as on incorporating assertion, relationship, and temporal data. The system will also support interaction with the human user. This does not only ensure correctness; by retaining all manually validated summary facts as well as any manual corrections, institutions' system performance can improve over time. Such incremental improvement will further reduce the time and effort required by a clinician to verify and correct a machine-generated summary.

Ultimately, a “living document” with its own place in the EHR might be semiautomatically updated as a patient proceeds through treatment; this document could capture adverse effects, regimen changes, and responses to treatment in a real-time fashion. Such a document would be expected to vastly improve interprovider communication and could also be provided to patients upon request. The development of software to enable creation of such documents should be vigorously pursued.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Jeremy L. Warner, Peter Anick, Pengyu Hong, Nianwen Xue

Collection and assembly of data: Jeremy L. Warner

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeremy L. Warner, Nianwen Xue

Manuscript writing: Jeremy L. Warner, Peter Anick

Final approval of manuscript: Jeremy L. Warner, Peter Anick, Pengyu Hong, Nianwen Xue

References

- 1.Ensuring continuity of care through electronic health records. Recommendations from the ASCO electronic health record roundtable. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:137–142. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0733501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNiff KK, Bonelli KR, Jacobson JO. Quality oncology practice initiative certification program: Overview, measure scoring methodology, and site assessment standards. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:270–276. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Society of Clinical Oncology. QOPI Summary of Measures, Fall. 2010. http://qopi.asco.org/Documents/QOPIFall2010MeasuresSummary.pdf.

- 4.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC); Department of Health and Human Services. Health information technology: Initial set of standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology—Final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75:44589–44654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demner-Fushman D, Chapman WW, McDonald CJ. What can natural language processing do for clinical decision support? J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:760–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melton GB, Hripcsak G. Automated detection of adverse events using natural language processing of discharge summaries. JAMIA. 2005;12:448–457. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savova GK, Fan J, Ye Z, et al. Discovering peripheral arterial disease cases from radiology notes using natural language processing. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:722–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denny JC, Peterson JF, Choma NN, et al. Development of a natural language processing system to identify timing and status of colonoscopy testing in electronic medical records. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sponsler JL. HPARSER: Extracting formal patient data from free text history and physical reports using natural language processing software. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001;2001:637–641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch of Psychology. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anick P, Hong P, Xue N, et al. I2B2 2010 challenge: Machine learning for information extraction from patient records. Presented at the Fourth i2b2/VA Workshop on Challenges in Natural Language Processing for Clinical Data; November 12-13, 2010; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]