Abstract

Biliary strictures are one of the most common complications following liver transplantation, representing an important cause of morbidity and mortality in transplant recipients. The reported incidence of biliary stricture is 5% to 15% following deceased donor liver transplantations and 28% to 32% following living donor liver transplantations. Bile duct strictures following liver transplantation are easily and conveniently classified as anastomotic strictures (AS) or non-anastomotic strictures (NAS). NAS are characterized by a far less favorable response to endoscopic management, higher recurrence rates, graft loss and the need for retransplantation. Current endoscopic strategies to correct biliary strictures following liver transplantation include repeated balloon dilatations and the placement of multiple side-by-side plastic stents. Endoscopic balloon dilatation with stent placement is successful in the majority of AS patients. In patients for whom gaining biliary access is technically difficult, a combined endoscopic and percutaneous/surgical approach proves quite useful. Future directions, including novel endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography techniques, advanced endoscopy, and improved stents could allow for a decreased number of interventions, increased intervals before retreatment, and decreased reliance on percutaneous and surgical modalities. The aim of this review is to detail the present status of endoscopy in the diagnosis, treatment, outcome, and future directions of biliary strictures related to orthotopic liver transplantation from the viewpoint of a clinical gastroenterologists.

Keywords: Liver transplantation, Anastomotic strictures, Bile duct diseases, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation is a life saving procedure for patients with chronic end-stage liver disease and acute liver failure when there are no available medical and surgical treatment.1-3 Since Thomas Starzl performed the first liver transplantation in 1963, there have been significant advances in all aspects of organ selection, retrieval, preservation, and implantation techniques. Therefore, the overall 1-year survival for adult and pediatric deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) is now expected to be in excess of 85%, with 5- and 10-year survival in excess of 70% and 60%, respectively.4-7 However, complications of the biliary tract remains a common source of morbidity and mortality. Some authors call it "Achilles heel of orthotopic liver transplantation."8

Biliary leaks and strictures are the most common biliary complications, but sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, hemobilia, and biliary obstruction from cystic duct mucocele, stones, sludges or casts have also been observed.9-11 The rate of bile leaks or strictures at the anastomotic site or cut edge of the transected liver, were reported in 15% to 60% of recipients in early, single center reports.12 These high rates of post-transplant biliary complications, may point to an inherently sensitive nature of the biliary epithelium to ischemic damage in comparison to hepatocytes and vascular endothelium.13

Improving survival of liver transplants, biliary complications also increased in long-term survival patients. These complications not only affect graft survival but also have a major impact on the quality of life for a liver allograft recipient, as they lead to frequent readmission, reoperation, hospital stays, and escalate costs and add to the emotional trauma that patients suffer.

Surgical repair traditionally has been the preferred approach in biliary complication of orthotopic liver transplantation. With advances in therapeutic and diagnostic endoscopy, the nonoperative management of biliary complications has become standard techniques as the preferred diagnostic and therapeutic modalities.

The aim of this review is to overview a present status of endoscopic role in the diagnosis, treatment, outcome, and future directions of biliary stricture related to orthotopic liver transplantation, from the viewpoints on clinical gastroenterologist.

INCIDENCE OF BILIARY STRICTURES

Studies regarding long-term outcomes after liver transplantation indicate that approximately 5% to 30% of recipients will develop biliary complications after transplantation. The most common biliary complications are bile leaks, anastomotic and intrahepatic strictures, stones, and ampullary dysfunction. Leaks predominate in the early posttransplant period (<3 months). Stricture formation typically develops gradually over time. Biliary strictures are the most frequent type of late biliary complication (>3 months) and are typically due to ischemia/reperfusion injury, vascular insufficiency, or fibrotic healing caused by improper technique.14-17

Although the strictures can present at any time after the surgery, the mean interval at the time of presentation is 5 to 8 months after orthotopic liver transplantation and the majority present within 1 year,17-22 but recent studies suggest that their prevalence continue to increase with the time after transplantation.23

CLASSIFICATION OF BILIARY STRICTURES

Bile duct strictures after liver transplantation are easily and conveniently classified as anastomotic strictures (AS) and non-anastomotic strictures (NAS). The clinical outcomes of the 2 types are markedly different, rendering their distinction clinically relevant.

NAS account for 10% to 25% of all stricture complications after orthotopic liver transplantation, with an incidence of 1% to 19%; these are often multiple, longer and occur earlier than anastomotic strictures. AS, on the other hand, are isolated, are localized to the site of the anastomosis, and are short in length. Their reported incidence in the modern literature is 4% to 9%.

PATHOGENESIS AND RISK FACTORS

1. AS

The underlying basis for AS includes ischemia or fibrosis following a suboptimal surgical technique or a bile leak in the postoperative period.21,23,24 Early in the postoperative period, technical issues appear to be the most important: improper surgical techniques, small caliber of the bile ducts, a mismatch in size between the donor and recipient bile ducts, inappropriate suture material, tension at the anastomosis, excessive use of electrocauterization for control of bile duct bleeding, and infection.8

Later onset anastomotic strictures most likely indicate fibrotic healing arising from ischemia at the end of the donor or recipient bile duct.14-16,21,23-25

According to some series of whole organ orthotopic liver transplantation, they are reported to be more common after hepaticojejunostomy than after direct duct-to-duct anastomosis,9,11,26 as well as following duct-to-duct anastomosis in non-T-tube recipients, as compared to the anastomosis over a T-tube.27-30 In right lobe living-donor transplants, the incidence of duct to duct anastomotic strictures has been consistently higher, as compared to recipients of whole liver grafts.31-35 This is considered to be related to the blood supply of the anastomosis and often the presence of multiple and small caliber donor ducts.

2. NAS

NAS are heterogeneous entities, and on the basis of the etiology, Moench et al.36 proposed a classification dividing them into NAS secondary to macroangiopathy and NAS secondary to microangiopathy (preservation injury, prolonged cold and warm ischemia times, donation after cardiac death, and prolonged use of vasopressors in the donor) and immunogenicity (chronic rejection, ABO incompatibility, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less important and inconsistent are the reported associations with hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus.11,37,38

NAS present earlier than AS, with the mean time to stricture development being 3.3 to 5.9 months.20,37 Verdonk et al.39 further reported that NAS secondary to ischemic causes presented within 1 year of the transplant, whereas the occurrence after 1 year was more often related to immunological causes as the risk factors.

PRESENTATION

Patients may be asymptomatic at presentation, with elevations of serum aminotransferases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase levels. A high index of suspicion must be maintained, as pain may be absent in the transplant setting because of immunosuppression and hepatic denervation.40-42

A recent report of 15 patients highlighted the use of serum bilirubin >1.5 mg/dL as a better indirect marker of biliary stasis in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) than alkaline phosphatase, which is overly sensitive.43

DIAGNOSIS

Initial evaluation should include liver ultrasound (US) with Doppler evaluation of the hepatic vessels. If hepatic artery stenosis or occlusion is suspected on Doppler US, hepatic angiography is usually indicated. Unfortunately, in liver transplant patients, abdominal US may not be sufficiently sensitive (sensitivity of 38% to 66%) to detect biliary obstruction.44

In addition, the size of the duct has not been found to be a reliable indicator in following up these patients or in accessing the response to the treatment. Furthermore, there is a significant lack of correlation between the ducal dilatation on the ultrasound and the cholangiographic and clinical feature. It is not clear why the donor bile ducts do not respond to distal obstruction by displaying the same degree of proportional dilation as non transplanted livers.43 However, It is possible that the presence of variable degrees of fibrosis subsequent to the injury sustained at the time of the perioperative period results in less pliable ducts.45

Scintigraphy of the hepatobiliary tract with 99-technetium labeled iminodiacetic acid identifies strictures with 75% sensitivity and 100% specificity but a lack of therapeutic benefit limits its clinical use.46,47

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which has a sensitivity and specificity close to 90% in establishing the diagnosis of biliary strictures.48-50 MRCP is currently considered an optimal noninvasive diagnostic tool for the assessment of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation.8 Once MRCP expertise becomes more widely available, it should have an even more prominent role in limiting the role of invasive cholangiography for therapeutic purposes. The chief disadvantage is the lack of its therapeutic ability. It can be used as the second step after ultrasound in patients for whom the use of diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) carries a higher operational risk. Cholangiography is considered by all to be the gold standard not only in establishing the diagnosis but also in allowing therapeutic intervention in the same setting.51,52 ERCP has the advantage over PTC and is the first modality of choice as it is not only more physiological but also less invasive. PTC is most often reserved for patients in whom ERCP is unsuccessful and in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy or choledochojejunostomy. However, newer approaches using the variable stiffness colonoscope, double balloon enteroscope, single balloon enteroscope, and spiral overtube have been made it possible to reach this difficult area.19,53-56 The characteristic ERCP findings in NAS consist of mucosal abnormalities, narrowing, and prestenotic dilatation, whereas the findings in AS include a thin, short, localized, isolated narrowing in the area of the biliary anastomosis (Fig. 1).

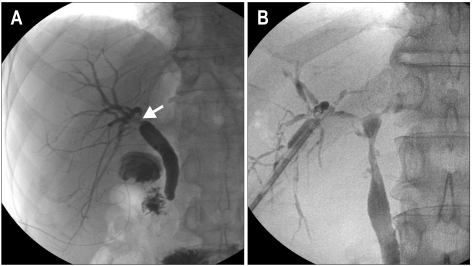

Fig. 1.

Cholangiogram of an anastomotic stricture and a non-anastomotic stricture. (A) Short localized anastomotic stricture (arrow). (B) A long nonanastomotic stricture extending proximally from the anastomosis site.

MANAGEMENT

Historically, the management of post-orthotopic liver transplantation biliary strictures consisted of surgical reconstruction in the form of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. However, the past 2 decades have seen tremendous growth in the evolution of endoscopic techniques that they are now considered the treatment of choice for biliary strictures.57-60

Percutaneous therapy, although it has a success rate of 40% to 85% is still considered a second-line option because of the invasive nature of procedure and the associated complications of hemorrhage, bile leaks and significant morbidity.61 Surgical revision is now reserved for patients who have failed the preceding measures, and retransplantation is the final option when all else fails.

1. NAS

Management of patients with NAS is difficult, and any generalized treatment recommendations are difficult to make. Accumulation of biliary sludge and casts renders therapy particularly difficult because of rapid stent occlusion. Treatment of NAS did not result in significant long-term improvement of liver chemistries. It does not appear that the poor response of non-anastomotic treatment to treatment varies with etiology.37 Most importantly, NAS resulted in significantly increased graft loss.

NAS are more resistant to endoscopic treatment, the results of endoscopic approaches have been particularly disappointing in the context of NAS in LDLT. The average success rate varies from 25% to 33%,32,62,63 which is way below the 60% success rate seen with NAS in DDLT.

Endoscopic therapy of non-anastomotic strictures typically consists of extraction of the biliary sludge and casts and balloon dilation of all accessible strictures followed by placement of plastic stents with replacement every 3 month.37 However, balloon dilation of all stricture is not feasible and rapid stent clogging is frequently occurred when managing NAS. Therefore, patients with NAS may required early retransplantation, endoscopic therapy appears to play a more prominent role as a bridge to liver retransplantation.14,64

2. AS

The conventional method of endoscopic treatment consists of identification of the opening of the stricture followed by cannulation by the guidewire, balloon dilatation of the stricture, and subsequent placement of plastic stents.

Balloon dilation alone without stent placement is only successful in approximately 40% of cases.60 However, Balloon dilation with additional stent placement appears to be more successful with a durable outcome in 75% of patients with anastomotic strictures.60,65 The stents are generally replaced by larger stents every 3 month to prevent the complication of clogging, cholangitis, or stone formation.59,60,66 Dual or multiple stents, by providing greater dilatation, have shown better results than single stents.20,60 Placement of not one, but multiple side-by-side plastic stents further increases successful outcomes in 80% to 90% of patients.59,67,68 In some patients, a transient narrowing at a duct to duct connection appear within the first 30 to 60 days after transplantation, due to postoperative edema and inflammation. This type of stricture responds well to balloon dilatation and temporary stent placement.42 Most patients with anastomotic strictures require ongoing ERCP sessions every 3 month with balloon dilation of 6 to 10 mm and multiple stents of 7 Fr to 10 Fr repeated for 12 to 24 months.42,59,68 An increasing number of stents can be used at each session to achieve a maximum diameter. The treatment is usually completed in 1 year with an average of 3 to 4 stent exchange sessions.18,21,59,66,69 Figs 2 and 3 illustrate the cholangiographic appearances of AS before and after endoscopic treatment in living and DDLT.

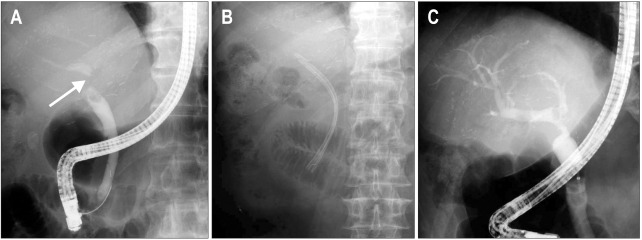

Fig. 2.

A case of anastomotic stricture in a living donor liver transplantation. (A) Retrograde cholangiogram showing a biliary stricture at the anastomotic site (arrow). (B) Insertion of two straight plastic stents across the anterior duct. (C) Six-month follow-up cholangiogram showing resolution of the stricture.

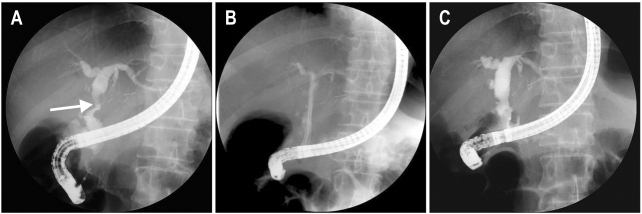

Fig. 3.

Case of anastomotic stricture in a deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT). (A) A biliary stricture is shown in the anastomosis site following the DDLT (arrow). (B) Two straight plastic stents were inserted through an anastomosis stricture. (C) The biliary stricture was resolved after 3 months.

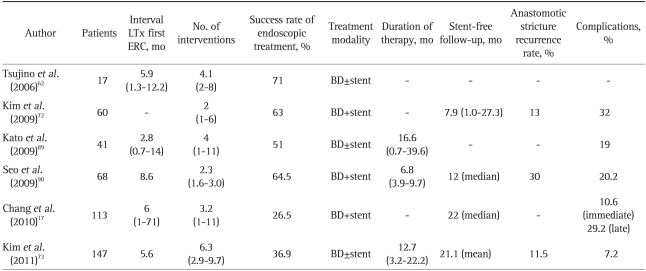

The overall long-term success rate of endoscopic treatment for AS associated with DDLT is in the range of 70% to 100%.18,20,21,57,59,66,69-71 However, endoscopic treatment success rates in AS after LDLT appears significantly less than AS for DDLT at 37% to 71% (Tables 1 and 2).62,72,73 When AS are treated appropriately, the long-term results in terms of patient and graft survival are equivalent to those for matched controls without AS.18,57,66,74 A protocol of accelerated dilation every 2 week, and a shortened stenting period of an average of 3.6 months, showed some encouraging results with a high 87% success rate.68

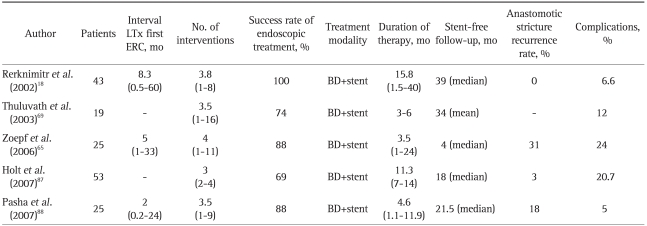

Table 1.

Results of Endoscopic Therapy of Post-Transplant Biliary Anastomotic Stricture in Transplants from a Deceased Donor: A Review of the Literature

LTx, liver transplantation; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; BD, balloon dilatation.

Table 2.

Results of Endoscopic Therapy of Post-Transplant Biliary Anastomic Stricture in Transplants from a Living Donor: A Review of the Literature

LTx, liver transplantation; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; BD, balloon dilatation.

In patients with duct to duct anastomosis, endoscopic management is hence first line, and it appears that while repeat endoscopic treatment is needed, shorter intervals in between treatments may ultimately reduce the time needed for successful long term outcomes. Despite of limited data, there is some experience in temporary placement of covered self-expanding metal stents to reduce the need for repeated stent exchanges but long term results not identified. In the few situations when endoscopic access to the AS is not obtainable, as in Roux-en-Y reconstructions, another option could be considered. A combined approach where access to the biliary tree is obtained via a percutaneous transhepatic route followed by "rendezvous" endoscopy.54,75 The use of percutaneous transhepatic drainage achieves success rates of 50% to 75%.76-79 Surgical revision and biliary reconstruction with the formation of a hepaticojejunostomy is indicated when endoscopic or percutaneous treatment fails.

ENDOSCOPY PROTOCOL

Endoscopic interventions were performed with duodenoscope after overnight fasting. After selective bile duct cannulation, anastomotic stricture could be detected as a dominant narrowing at the anastomotic site, without effective passage of contrast material, as identified by cholangiography. If the guidewire (0.025 or 0.035 inch) pass into the intrahepatic duct proximal to the site of the stricture, endoscopic sphincterotomy or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation was performed to allow placement of stent.

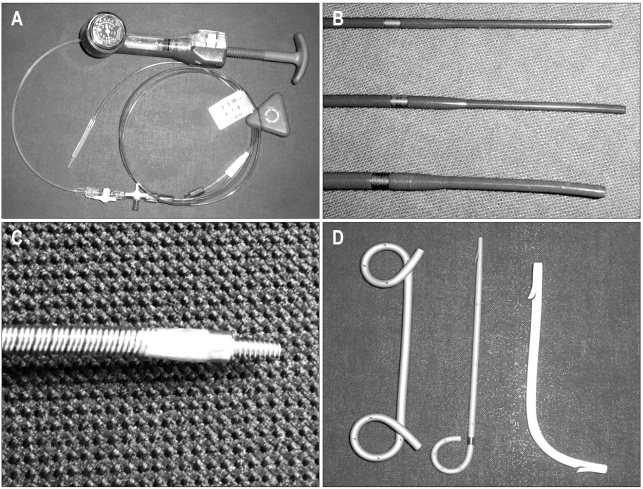

The anastomotic stricture was then dilated by using high pressure pneumatic balloons that ranged in size from 4 to 10 mm for 30 to 60 seconds. The Soehendra biliary dilation catheter or Soehendra stent retriever (Wilson-Cook Medical GI Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) was sometimes used to dilate the stricture site. A 7 to 10 Fr straight or pigtail plastic stent was inserted after balloon dilatation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Instruments used for biliary dilatation and stenting. (A) Controlled Radial Expansion (CRE) wire-guided balloon dilatation catheter (Boston Scientific Microvasive). (B) The tips of the Soehendra® biliary dilatation catheter and (C) a Soehendra® stent retriever. (D) From left to right, a double pig-tail stent (Solus double pigtail stent), a single pig-tail stent (Zimmon® pancreatic stent) and a straight plastic (Cotton-Leung® Amsterdam style biliary stent) stent (all produced by Wilson-Cook Medical GI endoscopy).

According to the characteristics of the stricture, including its location, severity of tightness, and angulation, we decided the number, size and form of the stents. For example, if an angulation was present near the stricture site and straightening and migration of the stent was anticipated, a double pig-tail stent was regarded as adequate. If the guidewire could not be passed through the stricture site or minimal narrowing at the anastomosis site that did not impede the flow of contrast material, the percutaneous transhepatic approach was used after the nasobiliary tube was placed distal to the stricture site.

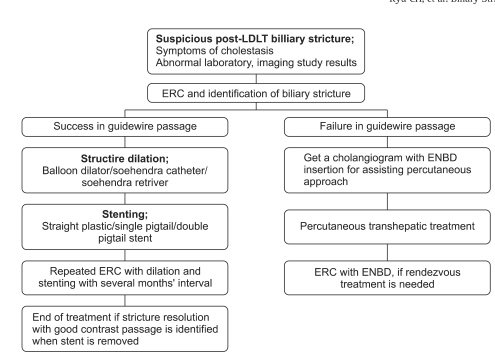

After the initial endoscopic session, ERCP was scheduled electively at intervals of 2 to 3 months for evaluation of the stricture and for stent change. ERCP was performed earlier in cases of cholangitis or worsening liver function. At follow-up ERCP, the stents were removed by using the polypectomy snare or rat tooth forceps. A cholangiogram by occluding the distal common bile duct with a distended retrieval balloon (8.5 to 15 mm) showed a patent anastomotic stricture, then treatment discontinued. If not, balloon dilatation and stent placement were repeated at intervals of 2 to 3 months until the stricture were resolved. Fig. 5 summarized the schematic diagram of therapeutic approach for post-LDLT with duct to duct biliary stricture.73

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the therapeutic approach for the treatment of post LDLT biliary stricture.

LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; ENBD, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage catheter.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Use of new intraductal endoscopy technologies such as the SpyGlass direct visualization system (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), which allows visualization of the inner wall of the biliary tree and can act as the guidance system for passage of the guidewire through a tight stricture, has shown some early promise in this area.61,80-82

New types of balloons and stents will have significant role in improvement of management of biliary stricture. Preliminary evidence shows that peripheral cutting balloons may be more effective in benign biliary stricture not responsive to standard measures.83 Metal stents have been employed in an effort to reduce stricture recurrence and maintain duct patency. Traditional open-mesh metal stents are associated with occlusion, stone formation, and lack of permanency, epithelial hyperplasia.84 These disadvantages of metal stents have traditionally limited their use in benign biliary strictures. The drawbacks of uncovered metal stents have led to the use of covered metal stents, with the potential benefit that these stents can be removed. However, the use of covered metal stents needs further evaluation to determine their therapeutic effectiveness. Self-expanding stents made of bioabsorbable material may offer several advantages compared to the plastic and self-expanding metal stents.85,86 Studies in porcine models show that these stents offer improved patency because of their large diameter, lower biofilm accumulation and reduced incidence of bile duct proliferative changes. Furthermore, patients do not have to undergo additional procedures to remove the stents. Bioabsorbable stents can be impregnated with pharmaceutical compounds, such as antimicrobial and antineoplastic agents. However, these stents remains investigational at the present time.

CONCLUSIONS

The landscape related to biliary complications after liver transplantation has changed rather rapidly in the past 2 decades. The conventional management of these conditions in the past was mainly surgical. However, therapeutic endoscopy plays an important role in the treatment of post-liver transplant anastomotic strictures. At present, the preferred endoscopic approach is repeated aggressive dilation of the stricture and insertion of multiple plastic stents, particularly anastomotic stricture. Percutaneous and surgical modalities are now reserved for patients in whom endoscopic treatment fails and for those with multiple inaccessible intrahepatic strictures or Roux-en-Y anastomoses. With advances of small bowel endoscopy, Roux-en-Y anastomosis site is accessible to endoscopic treatments. Fully covered metal stents or bioabsorbable stents may provide superior results and deserve further investigation. The area of therapeutic endoscopy will continue to evolve and offer opportunities for innovative new techniques in orthotopic liver transplantation patient related to biliary stricture.

References

- 1.Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Current indications and contraindications for liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:227–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray KF, Carithers RL, Jr AASLD. AASLD practice guidelines: evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1407–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consensus Conference: Indications for Liver Transplantation, January 19 and 20, 2005, Lyon-Palais Des Congrès: text of recommendations (long version) Liver Transpl. 2006;12:998–1011. doi: 10.1002/lt.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain A, Reyes J, Kashyap R, et al. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in 4,000 consecutive patients at a single center. Ann Surg. 2000;232:490–500. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbasoglu O, Levy MF, Brkic BB, et al. Ten years of liver transplantation: an evolving understanding of late graft loss. Transplantation. 1997;64:1801–1807. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asfar S, Metrakos P, Fryer J, et al. An analysis of late deaths after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:1377–1381. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon RD, Fung J, Tzakis AG, et al. Liver transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh, 1984 to 1990. Clin Transpl. 1991:105–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koneru B, Sterling MJ, Bahramipour PF. Bile duct strictures after liver transplantation: a changing landscape of the Achilles' heel. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:702–704. doi: 10.1002/lt.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greif F, Bronsther OL, Van Thiel DH, et al. The incidence, timing, and management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1994;219:40–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stratta RJ, Wood RP, Langnas AN, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Surgery. 1989;106:675–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colonna JO, 2nd, Shaked A, Gomes AS, et al. Biliary strictures complicating liver transplantation. Incidence, pathogenesis, management, and outcome. Ann Surg. 1992;216:344–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199209000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown RS., Jr Live donors in liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1802–1813. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noack K, Bronk SF, Kato A, Gores GJ. The greater vulnerability of bile duct cells to reoxygenation injury than to anoxia. Implications for the pathogenesis of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1993;56:495–500. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tung BY, Kimmey MB. Biliary complications of orthotopic liver transplantation. Dig Dis. 1999;17:133–144. doi: 10.1159/000016918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porayko MK, Kondo M, Steers JL. Liver transplantation: late complications of the biliary tract and their management. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:139–155. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Testa G, Malagò M, Broelseh CE. Complications of biliary tract in liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2001;25:1296–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang JH, Lee IS, Choi JY, et al. Biliary stricture after adult right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct anastomosis: long-term outcome and its related factors after endoscopic treatment. Gut Liver. 2010;4:226–233. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with choledochocholedochostomy anastomosis: endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:224–231. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.120813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thethy S, Thomson BN, Pleass H, et al. Management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718–725. doi: 10.1002/lt.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bourgeois N, Deviére J, Yeaton P, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JS, Kim MH, Lee SK, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments for biliary complications after cadaveric and living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:78–85. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, et al. Anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: causes and consequences. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:726–735. doi: 10.1002/lt.20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostroff JW. Post-transplant biliary problems. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:163–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagannath S, Kalloo AN. Biliary complications after liver transplantation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2002;5:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s11938-002-0057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor TP, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL. Biliary tract complications after liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 1995;130:312–317. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430030082017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouch DA, Emond JC, Thistlethwaite JR, Jr, Mayes JT, Broelsch CE. Choledochocholedochostomy without a T tube or internal stent in transplantation of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolles K, Dawson K, Novell R, Hayter B, Davidson B, Burroughs A. Biliary anastomosis after liver transplantation does not benefit from T tube splintage. Transplantation. 1994;57:402–404. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199402150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vougas V, Rela M, Gane E, et al. A prospective randomised trial of bile duct reconstruction at liver transplantation: T tube or no T tube? Transpl Int. 1996;9:392–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00335701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nuño J, Vicente E, Turrión VS, et al. Biliary tract reconstruction after liver transplantation: with or without T-tube? Transplant Proc. 1997;29:564–565. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sampietro R, Goffette P, Danse E, et al. Extension of the adult hepatic allograft pool using split liver transplantation. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2005;68:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yazumi S, Yoshimoto T, Hisatsune H, et al. Endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:502–510. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stapleton GN, Hickman R, Terblanche J. Blood supply of the right and left hepatic ducts. Br J Surg. 1998;85:202–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shokouh-Amiri MH, Grewal HP, Vera SR, Stratta RJ, Bagous W, Gaber AO. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in right lobe adult living donor liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:798–803. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spada M, Cescon M, Aluffi A, et al. Use of extended right grafts from in situ split livers in adult liver transplantation: a comparison with whole-liver transplants. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1164–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moench C, Moench K, Lohse AW, Thies J, Otto G. Prevention of ischemic-type biliary lesions by arterial back-table pressure perfusion. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:285–289. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guichelaar MM, Benson JT, Malinchoc M, Krom RA, Wiesner RH, Charlton MR. Risk factors for and clinical course of non-anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:885–890. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sankary HN, Rypins EB, Waxman K, et al. Effects of portacaval shunt and hepatic artery ligation on liver surface oxygen tension and effective hepatic blood flow. J Surg Res. 1987;42:7–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(87)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdonk RC, Buis CI, van der Jagt EJ, et al. Nonanastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation, part 2: management, outcome, and risk factors for disease progression. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:725–732. doi: 10.1002/lt.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, Haagsma EB. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: a review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;(243):89–101. doi: 10.1080/00365520600664375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Biliary complications after deceased-donor orthotopic liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:487–496. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thuluvath PJ, Pfau PR, Kimmey MB, Ginsberg GG. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: the role of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:857–863. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venu M, Brown RD, Lepe R, et al. Laboratory diagnosis and nonoperative management of biliary complications in living donor liver transplant patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:501–506. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000247986.95053.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma S, Gurakar A, Camci C, Jabbour N. Avoiding pitfalls: what an endoscopist should know in liver transplantation--part II. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1386–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St Peter S, Rodriquez-Davalos MI, Rodriguez-Luna HM, Harrison EM, Moss AA, Mulligan DC. Significance of proximal biliary dilatation in patients with anastomotic strictures after liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1207–1211. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000037814.96308.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macfarlane B, Davidson B, Dooley JS, et al. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in the diagnosis and endoscopic management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:1003–1006. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199610000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwarzenberg SJ, Sharp HL, Payne WD, et al. Biliary stricture in living-related donor liver transplantation: management with balloon dilation. Pediatr Transplant. 2002;6:132–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2002.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fulcher AS, Turner MA. Orthotopic liver transplantation: evaluation with MR cholangiography. Radiology. 1999;211:715–722. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99jn17715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linhares MM, Gonzalez AM, Goldman SM, et al. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in the diagnosis of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:947–948. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meersschaut V, Mortelé KJ, Troisi R, et al. Value of MR cholangiography in the evaluation of postoperative biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1576–1581. doi: 10.1007/s003300000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hussaini SH, Sheridan MB, Davies M. The predictive value of transabdominal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Gut. 1999;45:900–903. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurzawinski TR, Selves L, Farouk M, et al. Prospective study of hepatobiliary scintigraphy and endoscopic cholangiography for the detection of early biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 1997;84:620–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chahal P, Baron TH, Poterucha JJ, Rosen CB. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in post-orthotopic liver transplant population with Roux-en-Y biliary reconstruction. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1168–1173. doi: 10.1002/lt.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawano Y, Mizuta K, Hishikawa S, et al. Rendezvous penetration method using double-balloon endoscopy for complete anastomosis obstruction of hepaticojejunostomy after pediatric living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:385–387. doi: 10.1002/lt.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koornstra JJ, Fry L, Mönkemüller K. ERCP with the balloon-assisted enteroscopy technique: a systematic review. Dig Dis. 2008;26:324–329. doi: 10.1159/000177017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP using single-balloon instead of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2008;40(Suppl 2):E19–E20. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahajani RV, Cotler SJ, Uzer MF. Efficacy of endoscopic management of anastomotic biliary strictures after hepatic transplantation. Endoscopy. 2000;32:943–949. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rossi AF, Grosso C, Zanasi G, et al. Long-term efficacy of endoscopic stenting in patients with stricture of the biliary anastomosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 1998;30:360–366. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morelli J, Mulcahy HE, Willner IR, Cunningham JT, Draganov P. Long-term outcomes for patients with post-liver transplant anastomotic biliary strictures treated by endoscopic stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:374–379. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwartz DA, Petersen BT, Poterucha JJ, Gostout CJ. Endoscopic therapy of anastomotic bile duct strictures occurring after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759–769. doi: 10.1002/lt.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsujino T, Isayama H, Sugawara Y, et al. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2230–2236. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tada S, Yazumi S, Chiba T. Endoscopic management is an accepted first-line therapy for biliary complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1331. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zajko AB, Campbell WL, Logsdon GA, et al. Cholangiographic findings in hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:485–489. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, et al. Balloon dilatation vs. balloon dilatation plus bile duct endoprostheses for treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:88–94. doi: 10.1002/lt.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rizk RS, McVicar JP, Emond MJ, et al. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures in liver transplant recipients: effect on patient and graft survival. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:128–135. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Costamagna G, Pandolfi M, Mutignani M, Spada C, Perri V. Long-term results of endoscopic management of postoperative bile duct strictures with increasing numbers of stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:162–168. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.116876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morelli G, Fazel A, Judah J, Pan JJ, Forsmark C, Draganov P. Rapid-sequence endoscopic management of posttransplant anastomotic biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thuluvath PJ, Atassi T, Lee J. An endoscopic approach to biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2003;23:156–162. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2003.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chahin NJ, De Carlis L, Slim AO, et al. Long-term efficacy of endoscopic stenting in patients with stricture of the biliary anastomosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2738–2740. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alazmi WM, Fogel EL, Watkins JL, et al. Recurrence rate of anastomotic biliary strictures in patients who have had previous successful endoscopic therapy for anastomotic narrowing after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2006;38:571–574. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim ES, Lee BJ, Won JY, Choi JY, Lee DK. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage may serve as a successful rescue procedure in failed cases of endoscopic therapy for a post-living donor liver transplantation biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.03.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim TH, Lee SK, Han JH, et al. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for biliary stricture after adult living donor liver transplantation: technical aspect and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:188–196. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.522722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pfau PR, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, et al. Endoscopic management of postoperative biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:55–63. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matlock J, Freeman ML. Endoscopic therapy of benign biliary strictures. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2005;5:206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Civelli EM, Meroni R, Cozzi G, et al. The role of interventional radiology in biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation: a single-center experience. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:579–582. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roumilhac D, Poyet G, Sergent G, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous management for anastomotic biliary stricture after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:394–400. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sung RS, Campbell DA, Jr, Rudich SM, et al. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous transhepatic balloon cholangioplasty in the management of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:110–115. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000101518.19849.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zajko AB, Sheng R, Zetti GM, Madariaga JR, Bron KM. Transhepatic balloon dilation of biliary strictures in liver transplant patients: a 10-year experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bileduct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Judah JR, Draganov PV. Intraductal biliary and pancreatic endoscopy: an expanding scope of possibility. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3129–3136. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wright H, Sharma S, Gurakar A, Sebastian A, Kohli V, Jabbour N. Management of biliary stricture guided by the Spyglass Direct Visualization System in a liver transplant recipient: an innovative approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1201–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Atar E, Bachar GN, Bartal G, et al. Use of peripheral cutting balloon in the management of resistant benign ureteral and biliary strictures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(2 Pt 1):241–245. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000143767.87399.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Silvis SE, Sievert CE, Jr, Vennes JA, Abeyta BK, Brennecke LH. Comparison of covered versus uncovered wire mesh stents in the canine biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ginsberg G, Cope C, Shah J, et al. In vivo evaluation of a new bioabsorbable self-expanding biliary stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:777–784. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meng B, Wang J, Zhu N, Meng QY, Cui FZ, Xu YX. Study of biodegradable and self-expandable PLLA helical biliary stent in vivo and in vitro. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:611–617. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-9223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holt AP, Thorburn D, Mirza D, Gunson B, Wong T, Haydon G. A prospective study of standardized nonsurgical therapy in the management of biliary anastomotic strictures complicating liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:857–863. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000282805.33658.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pasha SF, Harrison ME, Das A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after deceased donor liver transplantation: outcomes after maximal stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kato H, Kawamoto H, Tsutsumi K, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic management for biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct reconstruction. Transpl Int. 2009;22:914–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seo JK, Ryu JK, Lee SH, et al. Endoscopic treatment for biliary stricture after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:369–380. doi: 10.1002/lt.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]