Abstract

The intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) that reside within the epithelium of the intestine form one of the main branches of the immune system. As IELs are located at this critical interface between the core of the body and the outside environment, they must balance protective immunity with an ability to safeguard the integrity of the epithelial barrier: failure to do so would compromise homeostasis of the organism. In this Review, we address how the unique development and functions of intestinal IELs allow them to achieve this balance.

The epithelium of the intestine digests and absorbs nutrients and fluids, and in adult humans it spans an area of about 200–400 m2 (REF. 1). This huge surface is made up of a single cell layer of epithelial cells, which lines the lumen of the intestine to form a physical barrier between the core of the body and the environment and forms the largest entry port for pathogens. Probably as a consequence of this, sophisticated and complex innate and adaptive immune networks intensely communicate and synergize to tightly control the integrity of this critical interface. Although a major task of the mucosal immune system is to provide protection against intestinal pathogens, it is important that excessive or unnecessary immune responses are avoided.

In this Review, we focus on the intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), which, by their direct contact with the enterocytes and by their immediate proximity to antigens in the gut lumen, form the front line of immune defence against invading pathogens. IELs essentially comprise antigen-experienced T cells belonging to both the T cell receptor-γδ (TCRγδ)+ and TCRαβ+ lineages. We discuss the thymic (natural) and peripheral (induced) differentiation of various IEL subpopulations, as well as their beneficial roles (that is, their ‘light side’) in preserving the integrity of the mucosal barrier and in preventing pathogen entry and spreading. Conversely, we also expose the ‘dark side’ of IELs and discuss how these cells can contribute to immune pathology and inflammatory diseases.

Mucosal IELs are unique and heterogeneous

IELs are extremely heterogeneous, and the various IEL subsets are distributed differently in the epithelium of the small and large intestine (TABLE 1). This pattern of distribution is probably influenced by the distinct digestive functions and the physiological conditions that allow these two compartments to cope with infections while simultaneously maintaining tolerance to innocuous antigens from the diet or from resident non-invasive commensals. Nevertheless, these IELs also share characteristics that distinguish them from the conventional T cell pools in the periphery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the different intestinal T cells subsets in mice

| Cell type | Characteristics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen dependency | IEL phenotype | Frequency of TCRγδ and TCRαβ IELs | Kinetics of accumulation | Development and TCR repertoire | Potential beneficial functions | Potential pathogenic functions | |

| Small intestinal epithelium | |||||||

| Natural IELs | Self and non-self | CD2− CD5− CD28−; CTLA4− THY1−/low; B220+/− CD69hi; NK receptors (+++++) |

TCRγδ+ (+++): − CD4−CD8− (++) − CD8αα+ (+++) TCRαβ+ (+++): − CD4−CD8− (+) − CD8αα+ (+++) |

Present at birth; decrease with age | ‘Alternative’ positive selection for CD8αα+TCRα β+ IELs in the thymus; oligoclonal TCR repertoire; unknown MHC restriction | Anti-inflammatory responses; antimicrobial responses; tolerance to intestinal antigens; immune regulation; homeostasis of the epithelium | Promote epithelial damage during intestinal inflammation |

| Induced IELs | Non-self | CD2+CD5+CD28+/−; CTLA4+/− THY1hi; B220− CD69hi; NK receptors (++++) |

TCRαβ+ (+++): − CD8αβ+ (+) − CD8αβ+ CD8αα+ (+++) − CD4+ (+) − CD4+ CD8αα+ (++) |

Absent at birth; increase with age | ‘Conventional’ positive selection in the thymus; oligoclonal TCR repertoire; restricted on MHC class I or MHC class II | Oral tolerance; protective antimicrobial responses | Excessive inflammation and cytotoxicity in response to luminal antigens; exacerbate coeliac disease |

| Small intestinal lamina propria | |||||||

| T cells | Non-self | Not applicable | TCRαβ (+++): − CD8αβ+ (++) − CD8αβ+ CD8αα+ (+) − CD4+ (+++) − CD4+ CD8αα+ (+) |

Absent at birth; increase with age | ‘Conventional’ positive selection in the thymus; polyclonal TCR repertoire; restricted on MHC class I or MHC class II | Oral tolerance; protective antimicrobial responses | Ileitis; inflammation |

| Large intestinal epithelium | |||||||

| Natural IELs | Self and non-self | CD2− CD5− CD28−; CTLA4−THY1−/low; B220+/−CD69hi; NK receptors (+++) |

TCRγδ+ (+): − CD4−CD8− (++) − CD8αα+ (+) TCRαβ (++): − CD4−CD8− (++) − CD8αα+ (+) |

Present at birth; decrease with age | ‘Alternative’ positive selection for CD8αα+TCR αβ+ IELs in the thymus; TCR repertoire and MHC restriction unknown | Anti-inflammatory responses; antimicrobial responses; tolerance to intestinal antigens | Promote epithelial damage during intestinal inflammation |

| Induced IELs | Non-self | CD2+CD5+CD28+; CTLA4+THY1hi; B220− CD69hi; NK receptors (++) |

TCRαβ+ (++): −CD8αβ+ (+) −CD8αβ+ CD8αα+ (+) −CD4+ (++) −CD4+ CD8αα+ (+) |

Absent at birth; increase with age | ‘Conventional’ positive selection in the thymus; TCR repertoire not defined; restricted on MHC class I or MHC class II | Protective antimicrobial responses | Drive excessive inflammation and cytotoxicity in response to microbiota-derived antigens; exacerbate IBD |

| Large intestinal lamina propria | |||||||

| T cells | Non-self | Not applicable | TCRαβ+ (+++): −CD8αβ+ (++) − CD8αβ+ CD8αα+ (+) − CD4+ (+++) − CD4+ CD8αα+ (+) |

Absent at birth; increase with age | ‘Conventional’ positive selection in the thymus; polyclonal TCR repertoire; restricted on MHC class I or MHC class II | Protective antimicrobial responses | Drive excessive inflammation and cytotoxicity in response to microbiota-derived antigens; exacerbate IBD |

Plus symbols represent frequency of expression, from low (+) to high (+++++). CTLA4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte A4; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease;

IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte; NK, natural killer; TCR, T cell receptor.

Gut IELs are almost exclusively T cells, and estimates based on histological sections indicate that there are more T cells in the intestinal epithelium than in the spleen2. IELs include a significant proportion of TCRγδ+ cells, which can constitute up to 60% of small intestinal IELs3–5. These IELs are antigen-experienced cells that typically express activation markers, such as CD44 and CD69 (REF. 6). Furthermore, studies using parabiotic mice and intestinal grafting indicate that these antigen-experienced T cells do not recirculate7,8. The majority of IELs contain abundant cytoplasmic granules for cyto-toxic activity, and they can express effector cytokines, such as interferon-γ (IFNγ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4 or IL-17 (REFS 9–16). Furthermore, they characteristically express both activating and inhibitory types of innate natural killer (NK) cell receptors, which typify them as stress-sensing (activated) yet highly regulated (resting) immune cells9,11,17–20.

IELs constitutively express CD103 (also known as the αE integrin), which interacts with E-cadherin on intestinal epithelial cells21,22, and most of them, especially in the small intestine, express CD8αα homodimers, which is a hallmark of their activated phenotype18,23–25 (BOX 1). A ligand for CD8αα, the thymus leukaemia antigen (TLA), which is a non-classical MHC class I molecule, is abundantly expressed on mouse small intestinal epithelial cells26,27. Many TCRαβ IELs express CD8αα together with CD4 or CD8αβ; however, a large fraction expresses CD8αα alone16. Finally, under normal conditions, and in contrast to systemic and lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs), CD4+ cells are greatly under-represented in the IEL compartment, especially in the small intestine28,29.

Box 1. CD8αα as a repressor.

CD8 αα, which is composed of two CD8α subunits, can be induced on activation through the T cell receptor (TCR)–CD3 complex, with the level of its expression being proportional with the signal strength. Therefore, CD8αα can be used as an activation marker for T cells43. CD8αα has the ability to recruit TCR–CD3 signalling components, including LCK (also known as p56LCK) and linker for activation of T cells (LAT)165. However, owing to its physical separation from the TCR-activation complex166, CD8αα neither functions as a TCR co-receptor nor can it substitute for the CD4 or CD8αβ co-receptors (see the figure, part a). Consistent with this, CD8αα is unable to support positive selection of MHC class I-restricted thymocytes or promote activation of mature MHC class I-restricted T cells167. Instead, co-expression of CD8αα on CD8αβ+ (or CD4+) T cells downmodulates, rather than enhances, the functional avidity of the MHC–TCR activation complex113. The ability of CD8αα to function as a negative regulator is partly due to its exclusion from the TCR activation complex (see the figure, part b). Consequently, CD8αα can sequester signalling components outside the immunological synapse, thereby interfering with their recruitment to the CD8αβ or the CD4 co-receptor–TCR–CD3 activation complex. Thus, CD8αα serves as a TCR repressor (see the figure, part b) rather than as a TCR co-receptor (see the figure, part a). See REF. 43 for further details.

Ag, antigen; APC, antigen-presenting cell; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif.

Although all IELs have an antigen-experienced phenotype, they can be divided into two major subsets based on the mechanisms by which they become activated and on the cognate antigens that they recognize. The ‘natural’ IELs (which were previously known as ‘type b’ IELs)5 acquire their activated phenotype during development in the thymus in the presence of self antigens, whereas the ‘induced’ IELs (which were previously known as ‘type a’ IELs)5 are the progeny of conventional T cells that are activated post-thymically in response to peripheral antigens (FIG. 1; TABLE 1).

Figure 1. Thymic and peripheral differentiation of natural and induced IELs.

In the thymus, immature CD4+CD8αβ+CD8αα+ (triple positive) thymocytes undergo agonist (‘alternative’) selection and differentiate into double-negative T cell receptor-αβ (TCRαβ)+ cells that are the precursors of natural TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). The TCRαβ+ natural IEL precursor cells partly acquire their antigen-experienced phenotype ‘naturally’ during selection with self antigens. In addition, the precursor cells for TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ natural IELs upregulate intestinal homing receptors during their maturation in the thymus, which allows these cells to directly seed the intestinal epithelium after they leave the thymus. CD4+CD8αβ+ (double positive) thymocytes undergo ‘conventional’ thymic selection and differentiate into naive CD4+ and CD8αβ+ TCRαβ+ T cells that migrate to the periphery. These naive T cells can differentiate into effector T cells in response to peripheral antigens and subsequently migrate to the gut and become incorporated into the induced IEL compartment. APC, antigen-presenting cell; MLNs, mesenteric lymph nodes.

Natural IELs

Natural IELs are either CD8αα+ or CD8αα− T cells that express TCRγδ or TCRαβ but do not express either CD4 or CD8αβ. Typically, they are also negative for expression of CD2, CD5, CD28, lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA1; also known as αLβ2 integrin) and THY1 (REFS 9,28,30,31). In addition, the majority of TCRαβ+ natural IELs are B220+CD44low/midCD69+, a phenotype that is rarely found among peripheral T cells32,33. Many of the natural IELs also share molecules expressed by NK cells, such as CD16, CD122, DNAX-activation protein 12 (DAP12; also known as TYROBP), lymphocyte antigen 49A (Ly49A), Ly49E, Ly49G2, and NK1.1 (REFS 9,18,34,35). Lastly, they frequently express a CD3 complex that is composed of either CD3ζ–FcεRIγ heterodimers or FcεRIγ–FcεRIγ homodimers instead of the CD3ζ–CD3ζ homodimers that are expressed by conventional T cells9,36–38.

Induced IELs

Induced IELs arise from conventional CD4+ or CD8αβ+ TCRαβ+ T cells, which are MHC class II-restricted and MHC class I-restricted, respectively. In contrast to the natural IELs, induced IELs acquire an activated phenotype in response to cognate antigens encountered in the periphery33,39–42. Consistent with this, they typically express a ‘memory-like phenotype’ (CD2+CD5+CD44+LFA1+THY1+)9,28,30, together with the activation marker CD8αα43 (BOX 1). Contrary to the polyclonal nature of the conventional T cells in the periphery, the TCR repertoire of induced IELs is oligoclonal and does not significantly overlap with the limited TCR repertoire of the natural TCRαβ+ IEL compartment44.

Thymic development of IEL precursor cells

Similarly to peripheral T cells, all IEL subsets are progeny of bone marrow precursor cells that initially develop in the thymus45. However, thymocyte maturation is not uniform, and multiple pathways exist that ultimately determine the diversity of mature T cells, including IELs.

Development of natural IELs

The origin and development of TCRγδ and TCRαβ natural IELs are the subjects of long-standing debates24,46–49 (BOX 2). For an overview of recent advances on this topic, we refer the reader to previously published reviews6,45,50,51. Briefly, the term ‘natural’ refers to the ontogeny of the precursor cells. For the natural IELs, these precursors go through an ‘alternative’ self-antigen-based thymic maturation process that results in the functional differentiation of mature CD4 and CD8αβ double-negative, TCRγδ-expressing or TCRαβ-expressing T cells that directly migrate to the intestinal epithelium23,24,52 (FIG. 1).

Box 2. The distinct pathways of CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IEL differentiation.

This Review does not aim to discuss the debates surrounding the importance of the thymic versus the extrathymic differentiation pathway for CD8αα+ T cell receptor-αβ (TCRαβ+) intestinal epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), as this has been extensively reviewed elsewhere47,48,168. Here, we give a brief overview of the data that have challenged or supported the thymic differentiation pathway. CD8αα+ IELs were originally thought to differentiate locally in the gut. This attractive idea was fuelled, in part, by the presence of self-reactive TCRs in their TCR repertoire, by supporting data derived from studies using athymic mouse models, and by the presence of haematopoietic immature cells in the small intestine that display characteristics of T cell precursor cells169,171. Nevertheless, ample data indicate that the absolute numbers of CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IELs in athymic mice are extremely reduced compared with euthymic mice16,172–174. These data therefore support the notion that the vast majority of CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IELs are the progeny of cells with a thymic origin. Other data suggest that, under certain experimental conditions, immature T cell-committed precursors may leave the thymus prematurely, before TCR rearrangements have occurred, and complete their maturation locally in the gut175. In conclusion, if indeed the gut contains precursors of bone marrow and thymic origin that have the potential under physiological conditions to further differentiate locally, multiple crucial questions remain unanswered. For example, under what circumstances is this local pathway functional? And how can the gut environment support selection? However, there is currently no evidence available to answer these questions.

Development of induced IELs

Induced IELs are the progeny of conventional CD4+ or CD8αβ+ TCRαβ+ T cells that are selected in the thymus. The development of conventional TCRαβ+ thymocytes, including selection and lineage commitment has been extensively reviewed elsewhere53–55. Following positive selection, mature thymocytes exit the thymus and reach the periphery as conventional naive CD4+ or CD8αβ+ TCRαβ+ T cells. In response to cognate antigens, they can further mature into antigen-experienced cells, including induced IELs (FIG. 1).

Local differentiation of IELs

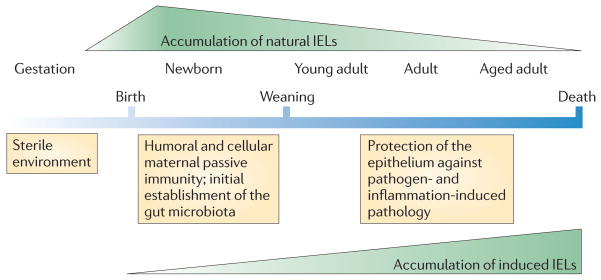

Because of the antigen-experienced phenotype that they acquire in the thymus, one can assume that the repertoire of the natural IELs is predominantly tuned to self antigens, whereas induced IELs are mainly shaped by non-self antigens encountered in the periphery. Consequently, induced IELs are sparse early in life, but the population steadily increases with age in response to exposure to exogenous antigens56–59 (FIG. 2; TABLE 1). The gradual accumulation of induced IELs allows the mucosal immune system to adapt and develop an almost ‘personalized’ mucosal immune repertoire that is directed against those environmental antigens that are most likely to be re-encountered by a particular individual. The development of these antigen-specific immune cells not only provides focused protective immunity at this mucosal interface but, at the same time, also reduces the risk of unwanted immune responses directed against innocuous antigens. By contrast, natural IELs do not depend on exogenous antigen-driven differentiation and so they are the first type of antigen-experienced T cells to populate the gut, even before birth60 (FIG. 2). Although direct evidence is still lacking, it is likely that the early accumulation of natural IELs provides a self-antigen-based, stress-sensing surveillance mechanism that is tolerant to dietary antigens and colonizing microbiota but provides protective immunity against stress-inducing invasive pathogens. With time, the population of induced IELs gradually becomes larger than the natural IEL population, which remains steady in actual numbers but represents a minor IEL population at later stages in life (FIG. 2).

Figure 2. Kinetics of the accumulation of natural and induced IELs.

Natural intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) gain their antigen-experienced phenotype and gut-homing capacity in the thymus during their initial agonist-based selection in response to self antigens. They populate the gut compartment early, before environmental antigens have been encountered. Conventional naive T cells differentiate into effector cells in response to peripherally encountered antigens and gradually accumulate over time as antigen-experienced induced IELs in the gut.

Nevertheless, regardless of the nature of the cognate antigens or the location of the initial differentiation, all IELs are directly influenced by the intestinal environment61. This was demonstrated with elegant studies in ‘germ-free’ and ‘antigen-free’ mice (the germ-free mice were fed an elementary diet), which showed that both the microbiota and dietary proteins have a crucial role in the establishment of a normal IEL repertoire, as virtually all IEL populations, with the exception of TCRγδ-expressing T cells, were markedly reduced in such an antigen-deprived environment62–64. Interestingly, although more than 95% of the commensal bacteria in the body normally reside in the large intestine, the small intestine contains at least ten times more IELs than the colon6. Furthermore, mice fed an amino-acid-based, protein-free diet, displayed a poorly developed intestinal immune system, similar to that of germ-free mice, with a strong decrease in most IEL populations65. These effects could be due to direct effects of the diet on the immune system or could result from diet-induced shaping of the intestinal microbiota. This highlights the importance of the diet, in addition to the microbiota, as a major driving factor in establishing and shaping this mucosal immune branch.

Migration of natural IELs

In addition to their antigen-experienced phenotype, natural IEL precursors may also acquire expression of gut-homing receptors (including αEβ7 integrin and CC-chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9)) in the thymus21,22,66–68. The expression of the ligands for αEβ7 integrin and CCR9, E-cadherin and CC-chemokine ligand 25 (CCL25), respectively, by small intestinal epithelial cells results in the direct recruitment of mature natural IEL precursors to the small intestinal epithelium24,66. Consistent with this, the seeding of mucosal tissues with these cells is independent of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1, also known as S1PR1), which is required for the migration of conventionally-selected T cells69. The direct and early population of the mucosal barrier with these stress-sensing self-reactive effector cells provides a layer of pre-existing immunity before the development of antigen-specific immune cells in response to exogenous antigens (FIG. 2). Additional local endogenous and exogenous factors, such as the cytokine IL-15 and vitamins A and D, further expand and adapt the natural IEL compartment. In light of this, a recent study showed that vitamin D receptor (VDR)-deficient mice had reduced numbers of CD8αα+ IELs and that this coincided with low levels of IL-10 in the small intestine and increased inflammation in the steady state70.

Migration of induced IELs

One study showed that, similarly to natural IELs, CD8αβ+ recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) can directly migrate to the small intestinal compartment66. However, in general, conventionally selected T cells do not express mucosal homing receptors and naive T cells are normally not detected within the intestinal epithelium. Instead, naive T cells acquire gut-homing capacity following priming in gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALTs), such as Peyer’s patches, and in mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs)71. Specialized intestinal epithelial cells or microfold cells (M cells), resident CX3C-chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1)+ macrophages and migratory CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs) all have the capacity to sample antigens in the gut and promote appropriate T cell responses42,72–75. On priming in mucosal sites, naive T cells upregulate homing receptors that allow them to enter intestinal tissues in response to specific ligands expressed by the tissues76. These receptor–ligand pairs include: LFA1 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1); very late antigen 1 (VLA1; also known as α1β1 integrin) and collagen; and α4β7 integrin and mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MADCAM1). α4β7 integrin can also be induced on T cells primed in other sites, allowing peripherally activated cells to migrate to the intestine71. Upregulation of CCR9 expression further directs T cells to the small intestine compartment in response to its ligand, CCL25, which is constitutively expressed by intestinal epithelial cells.

Induction of the receptors that promote migration of antigen-experienced T cells to the intestine can be promoted by environmental factors that are unique to the gut. It was shown that a diet-derived factor, the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid, is an important inducer of gut-homing molecules. Retinoic acid promotes upregulation of α4β7 integrin and CCR9, thereby directing activated T cells mainly to the small intestine77. Although migration to the colon is also dependent on α4β7 integrin78, retinoic acid seems to be neither necessary nor sufficient to induce migration to this site78,79. The ability to produce retinoic acid and to imprint gut-homing receptors during T cell priming is characteristic of the CCR7+CD103+ migratory DC subset77, which have been programmed previously by retinoic acid from intestinal epithelial cells and stromal cells80,81. It is important to note that mucosal imprinting is not absolutely required for entering the intestinal tissues, and T cells primed in the periphery also readily migrate to the gut as effector cells. However, in response to gut-derived antigens, the imprinting process might greatly focus the immune response to the mucosal effector site.

The main adhesion molecule that is involved in the specific localization of IELs in the epithelial layer is composed of CD103 and β7 integrin and interacts with E-cadherin on the basolateral surface of enterocytes. Expression of this integrin is induced by transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) and promoted by signalling through CCR9 (REFS 67,82–84). Nearly all activated cells that migrate to the intestinal epithelium gradually upregulate αEβ7 integrin, which coincides with the reciprocal downregulation of α4β7 integrin85. Upregulation of CD69 also occurs on entry into the intestinal mucosa; however, although CD69 has a role in inhibiting S1P1-mediated egress from the thymus and lymphoid tissues, its function on intestinal IELs remains elusive69.

The light side of IELs

The location of IELs at the intersection between the external environment and the core of the body prompts teleological predictions about their functions. These cells are geared to provide immediate and heightened immune protection to avoid initial entry and spreading of pathogens. However, because of their proximity to the fragile single cell layer of the intestinal epithelium, IELs also need to display regulatory functions and avoid excessive or unnecessary inflammatory immune responses that could jeopardize the integrity of the barrier (FIG. 3; TABLE 1).

Figure 3. The ‘light’ and ‘dark’ sides of intestinal IELs.

a | The ‘light side’ shows the beneficial roles of natural and induced intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) in preserving the epithelium and restoring tissue integrity after injury. b | The ‘dark side’ depicts the pathogenic roles of natural and induced IELs. IELs can exert uncontrolled and/or excessive cytotoxicity and promote inflammatory responses, which may initiate and/or exacerbate inflammatory bowel diseases and coeliac disease.

Protective functions of TCRγδ+ natural IELs

Although the exact functions and behaviour of natural IELs remain elusive, their primary role seems to be to ensure the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and to maintain local immune quiescence86–89.

TCRγδ+ natural IELs display dual roles: first, they condition and repair the epithelial barrier and control intestinal epithelial cell growth and turnover90,91, and second, they provide front-line defence against enteric pathogens89. TCRγδ+ natural IELs have been implicated in various regulatory roles, including in antibody class switching and immunoglobulin A (IgA) production, in IL-10-dependent oral tolerance, and in clearing necrotic epithelium and repairing damaged epithelium90,92–94. Furthermore, TCRγδ-deficient mice show abnormalities in gut epithelial morphology, reduced MHC class II expression by enterocytes and impaired mucosal IgA production89,94.

TCRγδ+ natural IELs also secrete several factors, including TGFβ1, TGFβ3 and prothymosin β4, that have direct or indirect roles in protecting the integrity of the epithelium9. In addition, their ability to secrete keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) is crucial for restoring the integrity of the epithelium in response to physical and inflammatory damage92,95–97. Exaggerated tissue damage is observed in TCRγδ-deficient mice following Listeria monocytogenes infection98–100 or during chemically induced colitis87,95,101; similarly, KGF-deficient mice are also more susceptible to dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. This suggests that, at least in mice, TCRγδ+ cells control intestinal homeostasis partly through the production of KGF95. TCRγδ+ natural IELs also express the co-stimulatory molecule junctional adhesion molecule-like (JAML), which is known to upregulate KGF expression following ligation by coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR), thereby linking this co-stimulatory pathway to the repair and maintenance functions of TCRγδ+ natural IELs102.

Many TCRγδ+ natural IELs express the inhibitory NK receptor NK group 2, member A (NKG2A), which, when triggered in conjunction with TCR activation, increases the production of intracellular and secreted TGFβ19, suggesting that these cells may also have suppressive roles. Consistent with this, TCRγδ+ natural IELs were shown to control the number and activation of cytotoxic CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs and to reduce the expression of the activating NK receptor NKG2D19. Furthermore, levels of IFNγ were greatly increased in TCRγδ-deficient mice infected with the protozoan parasite Eimeria vermiformis and in various models of chemically induced colitis89, whereas depletion of TCRγδ+ cells in IFNγ-deficient mice did not affect disease development during DSS-induced colitis87.

In addition to their maintenance and regulatory roles, TCRγδ+ natural IELs are also cytotoxic and they can contribute to protective immunity. This was shown in a model of Toxoplasma gondii infection, in which the presence of TCRγδ+ natural IELs greatly synergized with the resistance mediated by pathogen-specific CD8αβ+ T cells103,104. Furthermore, TCRγδ+ natural IELs also produce protective cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IFNγ105. Similarly to other TCRγδ+ T cells, TCRγδ+ natural IELs have a highly restricted TCR repertoire; however, substantial junctional and combinatorial diversity indicates that they have the potential to recognize a large variety of antigens, although these are still poorly defined106,107. Triggering of their TCRs does not seem to require antigen processing and presentation by MHC molecules, and they may recognize molecular patterns generated by bacterial non-peptide antigens108 or conserved unprocessed protein antigens (such as heat-shock proteins) produced by bacteria or stressed epithelial cells109.

The ability of TCRγδ+ natural IELs to, on the one hand, produce IFNγ in response to infections and, on the other hand, to control the production of IFNγ by other inflammatory cells, suggests that TCRγδ+ natural IELs are capable of protecting the mucosal barrier against exogenous insults as well as from self-induced damage during excessive immune responses.

Protective functions of CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs

Although self-reactive CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs are normally immunologically quiescent, they have a potent antigen-experienced cytotoxic effector phenotype, which is characterized by high levels of gran-zyme, CD95 ligand (CD95L; also known as FASL) and CD69 expression, but low levels of IFNγ production9,18. A specific function for these cells has not been described yet. However, as they differentiate in response to self antigens, possess a cytotoxic phenotype and show early localization to the gut epithelium, they might have important functions in maintaining and protecting the mucosal barrier at the time of gut colonization and before protective immunity towards exogenous antigens has been established in the intestine (FIG. 2). Furthermore, their proximity to the rapidly renewing intestinal epithelium suggests potential roles for CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs in sensing and eliminating cancerous or injured epithelial cells.

Nevertheless, although self reactive, these natural IELs are not self destructive, and evidence indicates that self tolerance and regulatory features are pre-programmed during agonist selection of their precursors in the thymus17,18,24. This notion is supported by the finding that when exposed in vitro to their cognate agonist antigens, surviving immature thymocytes induce an almost identical transcriptional signature as that described for CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs, including the expression of NK receptors, Ly49 members, CD94, SLAM-related receptor 2B4 (also known as CD244), DAP12 and FcεRIγ, together with the intestinal homing receptors CD103 and CCR9 (REFS 17,110). These observations underscore the importance of the thymic agonist selection process as a central mechanism to drive the antigen-experienced effector yet regulatory differentiation of these self-specific natural IELs.

We identified TCRαβ+ double-negative (CD4−CD8−) thymocytes that express co-receptor-independent high-affinity TCRs33,111 as the agonist-selected mature thymocytes, suggesting that agonist selection preserves and functionally imprints precursor cells with high-affinity TCRs. Agonist-selected CD4−CD8− cells that migrate to the intestine re-induce and maintain CD8αα expression. The re-induction of CD8αα expression on agonist-selected natural IELs is in part driven by IL-15 and does not require additional activation24. Furthermore, local interaction with TLA may further stabilize the constitutive expression of CD8αα and control the responsiveness of these cells23,25. In contrast to the conventional TCR co-receptors, CD4 and CD8αβ, CD8αα does not enhance, but instead suppresses TCR activation43 (BOX 1). Therefore, CD8αα expression by these high-affinity self-reactive natural IELs probably sets a new threshold for activation, which prevents or reduces the potential for unnecessary or auto-aggressive immune responses43. However, inhibition by CD8αα is not definite and can be overcome by high levels of antigen stimulation112,113.

CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs also express other molecules associated with immune regulation, including lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3), TGFβ, fibrinogen-like 2 (FGL2), prothymosin β4, 2B4, and several killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), such as Ly49A, Ly49E and Ly49G18. However, some of these receptors, such as 2B4, can also function as activating receptors and trigger cytotoxic responses114. The concomitant expression of effector and regulatory molecules implies that these ‘activated yet resting’ natural IELs may gain a full activation status to serve self-antigen-directed protective and/or regulatory functions9. Indeed, it was shown in a cell-transfer model of induced colitis that, when transferred in high numbers, self-reactive CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs could prevent inflammation induced by non-self-reactive naive CD4+CD45RBhi T cells86.

Protective functions of CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs

The intestinal tissue is particularly enriched for antigen-experienced cytotoxic CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ T cells115. Consistent with a protective role for these induced IELs, a recent study demonstrated that rhesus macaques inoculated with rhesus cytomegalovirus vectors containing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) epitopes were protected from progressive SIV infection following repeated low-dose intrarectal challenge116. The protected animals showed no evidence of systemic infection months later, suggesting that the infection was contained locally, preventing extensive viral replication or systemic spreading of the virus. Also, in mouse systems, experiments involving transfer of antigen-specific CD8αβ+ induced IELs to infected hosts demonstrated a protective role for these cells against various infectious agents, including lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)13, rotavirus117, T. gondii103 and Giardia lamblia118.

CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IEL effector memory cells are distinct from memory T cells in other tissues. For example, compared to splenocytes, CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs show limited homeostatic proliferation, but they are functionally more mature and show stronger and longer effector responses119. Furthermore, whereas a contraction phase is normally observed during T cell responses, induced IELs appear to maintain a long-term effector phase, and repeated challenges result in an enhanced and sustained cytotoxic effector phenotype120. Also, in the case of L. monocytogenes infection, oral infections seem to induce larger numbers of L. monocytogenes-specific CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs than do intravenous infections120,121. Moreover, L. monocytogenes-specific CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs display a distinct oligoclonal Vβ TCR repertoire, indicating that there is either selective migration or differential expansion and/or maintenance of primary and secondary CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ effector IELs122. The co-stimulatory requirements for induced IELs are also distinct. CD40L triggering is required for the CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IEL response, but the absence of CD40–CD40L interactions has little or no effect on splenic memory T cells120. These observations indicate that a second level of regulation dictated by intestine-specific cues controls the nature, magnitude, efficacy and specificity of these mucosal T cells. Furthermore, they imply that the unique functions of primary and memory CD8αβ+ induced IELs is greatly influenced by multiple factors, including the route of infection, the origin and nature of the antigen and other poorly defined cues that are present in the gut environment itself.

Protective functions of CD4+TCRαβ+ induced IELs

Although most induced IELs are CD8αβ+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), CD4+ T cells are also present within the epithelium, especially in the large intestine. The preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells from both the lamina propria and epithelial compartments during SIV or HIV infections123–127 impairs the integrity of the mucosal barrier and leads to translocation of enteric bacteria and increased local and systemic infections125. This highlights the importance of these T cells for protective immunity in the mucosa. Furthermore, recent data indicate that the HIV-mediated depletion of CD4+ T cells is initially preceded by an enhanced infiltration of systemic cytolytic effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that directly target the epithelium. These observations might indicate an important role for local IELs to not only protect against pathogen-induced damage of the epithelium but also prevent tissue destruction mediated by infiltrating peripheral effector T cells127. Furthermore, the suppressive functions of induced CD4+ Treg cells and the observation that most CD4+ T helper (TH) cell subsets (including TH1 and TH17 cells) display strong plasticity and can produce IL-10 under certain conditions, especially during chronic stimulation128,129, also support the notion that CD4+ IELs may contribute to regulatory mechanisms that prevent immunopathology in the intestine.

In the steady state, the gut environment is thought to favour anti-inflammatory immune responses, and migratory DCs, which produce TGFβ and retinoic acid, promote the induction of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+ Treg cells130–133. Nevertheless, under inflammatory conditions, TH-type induced IELs participate in protective immunity, especially in host defence against extracellular bacterial and fungal pathogens134. Finally, recent data have highlighted the intriguing phenomena of plasticity of CD4+ effector and regulatory T cells135,136, although protective and/or maintenance roles for such plastic CD4+ induced IELs remain to be investigated.

In this context, we recently generated data indicating that CD4+ effector T cells can upregulate CD8α and adopt a cytotoxic yet regulatory induced IEL phenotype in vivo (D.M., F. van Wijk, S. Muroi, R. Shinnakasu, Y. Naoe, J.-W. Shui, Y. Huang, M. Docherty, A. Attinger, G. Kim, C. J. Lena, O. Turovskaya, F.L., S. Sakaguchi, K. Atarashi, C. Miyamoto, W. Ellmeier, K. Honda, M. Kronenberg, I. Taniuchi and H.C., unpublished observations). This lineage-differentiation mechanism represents a new form of immune regulation that diverts effector CD4+ T cells away from becoming pro-inflammatory TH-type IELs. Therefore, we have defined a new subtype of CD4+ T cells that lose TH-like functions but gain adaptive and innate-like effector and regulatory functions. This restraint of the TH effector functions of CD4+ IELs but preservation of their protective and regulatory functions makes teleological sense at this mucosal interface, where effective protective immunity has to coincide with the least inflammatory damage. As the TCRs of these adapted cytotoxic CD4+ IELs remain MHC class II-restricted, they are capable of detecting infected intestinal epithelial cells that have upregulated expression of MHC class II molecules137 and they may also provide immediate protection against viruses that have developed mechanisms to evade detection by the MHC class I-restricted CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs138,139. Furthermore, under steady-state conditions, these CD4+ cytotoxic IELs may also contribute to tolerance by eliminating MHC class II-expressing migratory DCs, thereby preventing these DCs from priming T cell responses against innocuous antigens derived from the diet or commensal bacteria.

The dark side of IELs

As noted above, the differentiation, activation and functional specialization of all IEL subsets are regulated by interactions with other cell types and soluble factors, and are highly influenced by dietary and microbial products in the gut. The dynamic interactions between environmental cues and the mucosal adaptive immune system help maintain a stable equilibrium and sustain barrier function. Nevertheless, the heightened activation status of IELs and their close proximity to the intestinal epithelium suggest that these cells may contribute to immunopathological responses and initiate and/or exacerbate inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and coeliac disease, or promote cancer development and progression (FIG. 3; TABLE 1).

Pathological functions of natural IELs

Although TCRγδ+ natural IELs have important regulatory and protective roles, other evidence exposes a rather dark side of these IELs as well. Several reports indicate that there is a direct correlation between the numbers of TCRγδ+ cells in the intestinal mucosa and disease severity in patients with IBD140–142. Also, direct evidence showing that γδ+ cells promote immunopathology in various mouse models of IBD suggests a pro-inflammatory role for γδ+ natural IELs105,143,144. However, as some of these studies used TCRα-deficient mice or TCRβ-deficient mice, both of which contain aberrant γδ+ T cell populations, it is possible that the pro-inflammatory nature of γδ+ natural IELs in those particular studies was an experimental artefact. In another model of spontaneous colitis induced by deletion of phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) in T cells, γδ+ IELs were shown to be responsible for the colitis induction, presumably through the secretion of IL-17 (REF. 145).

Unlike conventionally selected T cells, CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs tend to express self-reactive TCRs. Despite this, in the steady state, CD8αα+TCRαβ+ natural IELs do not promote autoimmune tissue damage but instead show self-antigen-driven regulatory functions86. However, it remains possible, under inflammatory conditions or on recognition of foreign antigens with high similarity to self, that these auto-reactive T cells may drive autoimmune pathology. Furthermore, although normally these IELs show a higher threshold for TCR activation compared with conventional T cells146, increased or uncontrolled inflammatory conditions, or excessive production of IL-15, may trigger their autoreactive cytotoxicity, thereby jeopardizing the integrity of the mucosal barrier.

Pathological functions of CD8αβ+ induced IELs

Although recent data indicate important roles for cytotoxic CD8αβ+ induced IELs in protecting against invading pathogens, these cells have also been implicated in the progression147, or even initiation, of IBD. For example, in a transfer model of induced colitis, naive CD8αβ+ T cells were shown to induce colitis in an IL-17-dependent fashion148. Furthermore, in a hapten-induced model of colitis, previously sensitized hapten-specific CD8+ effector CTLs were found to initiate the inflammatory response149. Interestingly, in this study, the pathology induced by the CD8+ CTLs did not induce a chronic inflammation and the colitic mice gradually recovered149. Hapten-specific CD8+ effector T cells were not all deleted and some differentiated into long-lived IELs, which caused relapse of disease on secondary challenge of recovered animals. Despite their destructive cytotoxic attacks on the intestinal epithelium, these IELs had differentiated post-thymically and were not self-reactive natural IELs149.

Induced IELs have also been shown to exacerbate coeliac disease. In this setting, TCR-activated CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ induced IELs cause severe villous atrophy by targeting intestinal epithelial cells that express stress-induced MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence (MIC) antigens, in an NKG2D-dependent fashion150,151. Furthermore, IL-15, a cytokine that is over-expressed by enterocytes from individuals with Crohn’s disease, is known to trigger potent cytotoxic responses by CD8αβ+ induced IELs through the NKG2D–DAP10 signalling pathway150.

CD4+ induced IELs and intestinal disease

Aberrant differentiation and/or functions of mucosal CD4+ TH cell subsets are major contributing factors to immunopathology at mucosal sites. Perhaps the most significant detrimental effect of CD4+ induced IELs is their ability, in conjunction with CD4+ T cells in the lamina propria, to promote the development of small intestinal inflammation in patients with coeliac disease (reviewed in REF. 152). Contrary to other common inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, which mostly affect the large intestine, coeliac disease primarily affects the small intestine. The disease develops in genetically susceptible individuals that express HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8. These MHC class II molecules bind gluten peptides with strong affinity and, under inflammatory conditions, are greatly induced on enterocytes, which then become targets for gluten-specific CD4+ effector T cells152.

The exact role of CD4+ T cells in coeliac disease is still not clear, but the excessive production of IFNγ, which may enhance HLA-E expression by intestinal epithelial cells and promote bystander cytotoxic responses by CD8αβ+ and/or CD4+ TCRαβ+ induced IELs through the innate CD94–NKG2D pathway, is likely to be a key mechanism involved in the disease development153. IFNγ and IL-21 double-producing CD4+ T cells154, and more recently TH17 cells 155, have been implicated in coeliac disease as well. The differentiation of pathogenic CD4+ T cells is thought to be fuelled by high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-15 and IFN-α, that are present in the intestinal mucosa from patients with coeliac disease152. IL-15 may also interfere with immune regulation by disrupting TGFβ-mediated signalling through SMAD3 (REF. 156). In this context, a recent study reported that IL-15 may also synergize with retinoic acid to enhance inflammatory responses157. This is in sharp contrast to the anti-inflammatory effects of retinoic acid in conjunction with TGFβ, which in the absence of IL-15 promotes Treg cell differentiation and suppresses inflammatory TH17 cell differentiation130.

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are also generally thought to be driven by aberrant CD4+ IEL and LPL responses, in this case directed against the intestinal microbiota (for extensive reviews on this topic, see REFS 158,159). Although both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis share some important end-stage pathways of tissue damage, they represent immunologically different diseases with distinct effector CD4+ T cell types involved. Crohn’s disease is considered to be a classical TH1-cell-mediated inflammatory disorder that is characterized by elevated levels of IFNγ and IL-12. However, the more recent findings that inflamed colons from both mouse models and patients with Crohn’s disease show considerable TH17 cell infiltrates, suggests a more complex disorder. In addition, IL-23, which promotes TH17 cell responses, seems to be a major player in IBD pathogenesis160,161, and genome-wide association studies in humans defined IL-23R as one of the major IBD-susceptibility genes162. By contrast, ulcerative colitis has been associated with TH2 cell responses and is connected to elevated levels of IL-5 and IL-13 (REF. 163). Recent studies have also pointed to roles for thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and the IL-17 family member IL-25 in the induction of CD4+ T cell-driven intestinal inflammation164; this warrants further exploration in the context of ulcerative colitis. Further studies are also needed to distinguish the exact contribution made by IELs in the inflamed intestine from that made by infiltrating systemic and lamina propria T cells.

Overall, although all effector T cells, including the various IEL subsets, have the potential to initiate or propagate gut inflammation, aberrant or uncontrolled TH-type induced IELs are almost always involved and play a big part in the destructive immune pathology that jeopardizes the barrier function of the mucosal epithelium.

Conclusions and perspective

IELs are engaged in a constant, complex, multidirectional dialogue with epithelial cells and other cells in the gut environment. Their uniqueness, in terms of their location, their development pathways, their diverse self and non-self antigen specificity and their innate and adaptive functional specialization, allows these extraordinary effector T cells to provide the first line of defence at the most vulnerable entry port for pathogens. At the same time, they also protect the integrity of the mucosal border by preventing uncontrolled immune cell infiltration and excessive or unnecessary immune responses mediated by the systemic conventional T cells (FIG. 3; TABLE 1). Although IELs have many beneficial roles geared toward maintaining a stable equilibrium and sustained barrier function, they also have a dark side, and the combination of potent effector cells that are in direct contact with the epithelial target cells provides the IELs with the opportunity to mediate pathological responses that drive and exacerbate detrimental inflammatory diseases (FIG. 3; TABLE 1).

Understanding the differentiation pathways and communication networks that programme, wire and control these immune cells may provide new insights for the design of new and effective mucosal vaccines to prevent and combat infections and for the development of therapies to prevent and/or treat inflammatory diseases, food allergies and cancers.

Acknowledgments

This is the manuscript number 1364 of the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, California, USA. We thank F. van Wijk for helpful discussions and M. Cheroutre for her contribution. Work in the H.C. laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI050265-06) and the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology. Work in the D.M. laboratory is supported by The Rockefeller University, New York, USA, and by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Glossary

- Pathogens

Opportunistic organisms that cause acute or chronic disease following host infection. Derived from the Greek word ‘pathos’, which means ‘suffering’

- Intraepithelial lymphocytes

(IELs). These lymphocyte populations consist mostly of T cells and are found within the epithelial layer of mammalian mucosal linings, such as the gastrointestinal tract and reproductive tract. However, unlike conventional naive T cells, IELs are antigen-experienced T cells and, on encountering antigens, they immediately release cytokines or mediate killing of infected target cells

- Thymus leukaemia antigen

(TLA). A non-polymorphic, non-classical MHC class I molecule (MHC class I-b family) with a restricted expression pattern. It is constitutively expressed on intestinal epithelial cells and can be induced on antigen-presenting cells. TLA is structurally incapable of binding or presenting peptide antigens and it does not engage with T cell receptors. However, the α3 extracellular domain of TLA interacts with CD8α. TLA displays stronger affinity for CD8αα homodimers compared with CD8αβ heterodimers, and CD8αα expression can be detected with TLA-specific tetramers

- Lamina propria

Connective tissue that underlies the epithelium of the mucosa and contains various myeloid and lymphoid cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, T cells and B cells

- Microbiota

The microorganisms present in normal, healthy individuals. These microorganisms live mostly in the digestive tract but are also found in some other tissues

- Germ-free mice

Mice born and raised in sterile isolators. They are devoid of colonizing microorganisms, but after they have been experimentally colonized by known bacteria, they are said to be gnotobiotic

- Gut-associated lymphoid tissues

Lymphoid structures and aggregates associated with the intestinal mucosa, specifically the tonsils, Peyer’s patches, lymphoid follicles, appendix and caecal patch. Enriched in lymphocytes and specialized dendritic cell and macrophage subsets

- Peyer’s patches

Groups of lymphoid nodules present in the small intestine (usually the ileum). They occur in the intestinal wall, opposite the line of attachment of the mesentery. They consist of a dome area, B cell follicles and interfollicular T cell areas. High endothelial venules are present mainly in the interfollicular areas

- Mesenteric lymph nodes

Lymph nodes, located at the base of the mesentery, that collect lymph (including cells and antigens) draining from the intestinal mucosa

- Microfold cells

(M cells). Specialized antigen-sampling cells that are located in the follicle-associated epithelium of the organized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues. M cells deliver antigens by transepithelial vesicular transport from the aero-digestive lumen directly to subepithelial lymphoid tissues of nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue and Peyer’s patches

- NKG2D

(Natural killer group 2, member D). A lectin-type activating receptor that is encoded by the NK complex and is expressed at the surface of NK cells, NKT cells, natural and induced intraepithelial lymphocytes and conventional T cell receptor-γδ (TCRγδ) T cells, as well as some conventional cytolytic CD8αβ+TCRαβ+ T cells. The ligands for NKG2D are MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA) and MICB in humans, and retinoic acid early transcript 1 (RAE1) and H60 in mice. Such ligands are generally expressed at the surface of infected, stressed or transformed cells

- Inflammatory bowel disease

A chronic condition of the intestine that is characterized by severe inflammation and mucosal tissue destruction. The most common forms in humans are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

- Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is a condition that damages the lining of the small intestine and interferes with nutrient absorption. The damage is due to an aberrant immune response to gluten-derived antigens, which are found in wheat, barley, rye and possibly oats

- Crohn’s disease

A form of chronic inflammatory bowel disease that can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract but is most common in the colon and terminal ileum. It is characterized by transmural inflammation, strictures and granuloma formation, and it is thought to result from an abnormal T cell-mediated immune response to commensal bacteria

- Ulcerative colitis

A chronic disease that is characterized by inflammation of the mucosa and sub-mucosa tissues, mainly of the large intestine

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nature Rev Immunol. 2010;10:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darlington D, Rogers AW. Epithelial lymphocytes in the small intestine of the mouse. J Anat. 1966;100:813–830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonneville M, et al. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes are a distinct set of γδ T cells. Nature. 1988;336:479–481. doi: 10.1038/336479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman T, Lefrancois L. Expression of the γ-δ T-cell receptor on intestinal CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nature. 1988;333:855–858. doi: 10.1038/333855a0. References 3 and 4 describe the high frequency of TCR γδ-expressing T cells among IELs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guy-Grand D, et al. Two gut intraepithelial CD8+ lymphocyte populations with different T cell receptors: a role for the gut epithelium in T cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:471–481. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheroutre H. Starting at the beginning: new perspectives on the biology of mucosal T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugahara S, et al. Extrathymic derivation of gut lymphocytes in parabiotic mice. Immunology. 1999;96:57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki S, et al. Low level of mixing of partner cells seen in extrathymic T cells in the liver and intestine of parabiotic mice: its biological implication. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3719–3729. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3719::AID-IMMU3719>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC. Biological insights into γδ+ and TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes provided by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Immunity. 2001;15:419–434. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00192-3. One of the first studies to describe the cytotoxic function of IELs against virus-infected intestinal epithelial cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Offit PA, Dudzik KI. Rotavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes appear at the intestinal mucosal surface after rotavirus infection. J Virol. 1989;63:3507–3512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.8.3507-3512.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang F, et al. Cytosolic PLA2 is required for CTL-mediated immunopathology of celiac disease via NKG2D and IL-15. J Exp Med. 2009;206:707–719. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chardes T, Buzoni-Gatel D, Lepage A, Bernard F, Bout D. Toxoplasma gondii oral infection induces specific cytotoxic CD8α/β+ Thy-1+ gut intraepithelial lymphocytes, lytic for parasite-infected enterocytes. J Immunol. 1994;153:4596–4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller S, Buhler-Jungo M, Mueller C. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes exert potent protective cytotoxic activity during an acute virus infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1986–1994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts AI, O’Connell SM, Biancone L, Brolin RE, Ebert EC. Spontaneous cytotoxicity of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: clues to the mechanism. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:527–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb08229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebert EC, Roberts AI. Lymphokine-activated killing by human intestinal lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1993;146:107–116. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy-Grand D, Malassis-Seris M, Briottet C, Vassalli P. Cytotoxic differentiation of mouse gut thymodependent and independent intraepithelial T lymphocytes is induced locally. Correlation between functional assays, presence of perforin and granzyme transcripts, and cytoplasmic granules. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1549–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamagata T, Mathis D, Benoist C. Self-reactivity in thymic double-positive cells commits cells to a CD8αα lineage with characteristics of innate immune cells. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:597–605. doi: 10.1038/ni1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denning TL, et al. Mouse TCRαβ+ CD8αα intraepithelial lymphocytes express genes that down-regulate their antigen reactivity and suppress immune responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:4230–4239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4230. References 17 and 18 suggest that CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IEL precursor cells acquire functional specialization during their differentiation in the thymus. Their unique functional and phenotypic differentiation is reflected in the gene signature that they display at the mature stage as CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IELs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhagat G, et al. Small intestinal CD8+γδ+NKG2A+ intraepithelial lymphocytes have attributes of regulatory cells in patients with celiac disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:281–293. doi: 10.1172/JCI30989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou R, Wei H, Sun R, Zhang J, Tian Z. NKG2D recognition mediates Toll-like receptor 3 signaling-induced breakdown of epithelial homeostasis in the small intestines of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7512–7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700822104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cepek KL, et al. Adhesion between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes mediated by E-cadherin and the αEβ7 integrin. Nature. 1994;372:190–193. doi: 10.1038/372190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilshaw PJ, Murant SJ. A new surface antigen on intraepithelial lymphocytes in the intestine. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2201–2207. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leishman AJ, et al. Precursors of functional MHC class I- or class II-restricted CD8αα+ T cells are positively selected in the thymus by agonist self-peptides. Immunity. 2002;16:355–364. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00284-4. The first report to describe the thymic agonist selection pathway for MHC class-I- and MHC class-II-restricted IELs using TCR transgenic models. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gangadharan D, et al. Identification of pre- and postselection TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocyte precursors in the thymus. Immunity. 2006;25:631–641. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madakamutil LT, et al. CD8αα-mediated survival and differentiation of CD8 memory T cell precursors. Science. 2004;304:590–593. doi: 10.1126/science.1092316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hershberg R, et al. Expression of the thymus leukemia antigen in mouse intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9727–9731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leishman AJ, et al. T cell responses modulated through interaction between CD8αα and the nonclassical MHC class I molecule, TL. Science. 2001;294:1936–1939. doi: 10.1126/science.1063564. Identified TLA as a high-affinity ligand for CD8αα and showed functional effects of the interaction between TLA and CD8αα homodimers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefrancois L. Phenotypic complexity of intraepithelial lymphocytes of the small intestine. J Immunol. 1991;147:1746–1751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosley RL, Styre D, Klein JR. CD4+CD8+ murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1990;2:361–365. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohteki T, MacDonald HR. Expression of the CD28 costimulatory molecule on subsets of murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes correlates with lineage and responsiveness. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1251–1255. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Houten N, Mixter PF, Wolfe J, Budd RC. CD2 expression on murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes is bimodal and defines proliferative capacity. Int Immunol. 1993;5:665–672. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin T, et al. CD3−CD8+ intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) and the extrathymic development of IEL. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1080–1087. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang R, Wang-Zhu Y, Grey H. Interactions between double positive thymocytes and high affinity ligands presented by cortical epithelial cells generate double negative thymocytes with T cell regulatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2181–2186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042692799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guy-Grand D, Cuenod-Jabri B, Malassis-Seris M, Selz F, Vassalli P. Complexity of the mouse gut T cell immune system: identification of two distinct natural killer T cell intraepithelial lineages. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2248–2256. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huleatt JW, Lefrancois L. Antigen-driven induction of CD11c on intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:5684–5693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guy-Grand D, et al. Different use of T cell receptor transducing modules in two populations of gut intraepithelial lymphocytes are related to distinct pathways of T cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1994;180:673–679. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohno H, Ono S, Hirayama N, Shimada S, Saito T. Preferential usage of the Fc receptor γ chain in the T cell antigen receptor complex by γ/δ T cells localized in epithelia. J Exp Med. 1994;179:365–369. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park SY, et al. Differential contribution of the FcR γ chain to the surface expression of the T cell receptor among T cells localized in epithelia: analysis of FcR γ-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2107–2110. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arstila T, et al. Identical T cell clones are located within the mouse gut epithelium and lamina propia and circulate in the thoracic duct lymph. J Exp Med. 2000;191:823–834. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lefrancois L, Masopust D. T cell immunity in lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:503–508. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mowat AM. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nature Rev Immunol. 2003;3:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nri1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neutra MR, Mantis NJ, Kraehenbuhl JP. Collaboration of epithelial cells with organized mucosal lymphoid tissues. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni1101-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheroutre H, Lambolez F. Doubting the TCR coreceptor function of CD8αα. Immunity. 2008;28:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regnault A, Cumano A, Vassalli P, Guy-Grand D, Kourilsky P. Oligoclonal repertoire of the CD8αα and the CD8αβ TCR-α/β murine intestinal intraepithelial T lymphocytes: evidence for the random emergence of T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1345–1358. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1345. This study describes the oligoclonal repertoire of TCRαβ+ IELs in mice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheroutre H, Lambolez F. The thymus chapter in the life of gut-specific intra epithelial lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishikawa H, et al. Curriculum vitae of intestinal intraepithelial T cells: their developmental and behavioral characteristics. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:154–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambolez F, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Thymic differentiation of TCRαβ+ CD8αα+ IELs. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:178–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha B. The extrathymic T-cell differentiation in the murine gut. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:166–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberl G, Littman DR. Thymic origin of intestinal αβ T cells revealed by fate mapping of RORγt+ cells. Science. 2004;305:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1096472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheroutre H, Mucida D, Lambolez F. The importance of being earnestly selfish. Nature Immunol. 2009;10:1047–1049. doi: 10.1038/ni1009-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogquist KA, Baldwin TA, Jameson SC. Central tolerance: learning self-control in the thymus. Nature Rev Immunol. 2005;5:772–782. doi: 10.1038/nri1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen KD, et al. Thymic selection determines γδ T cell effector fate: antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon γ. Immunity. 2008;29:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carpenter AC, Bosselut R. Decision checkpoints in the thymus. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:666–673. doi: 10.1038/ni.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins A, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. Nature Rev Immunol. 2009;9:106–115. doi: 10.1038/nri2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4-versus CD8-lineage choice. Nature Rev Immunol. 2008;8:788–801. doi: 10.1038/nri2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manzano M, Abadia-Molina AC, Garcia-Olivares E, Gil A, Rueda R. Absolute counts and distribution of lymphocyte subsets in small intestine of BALB/c mice change during weaning. J Nutr. 2002;132:2757–2762. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helgeland L, Brandtzaeg P, Rolstad B, Vaage JT. Sequential development of intraepithelial γδ and αβ T lymphocytes expressing CD8αβ in neonatal rat intestine: requirement for the thymus. Immunology. 1997;92:447–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steege JC, Buurman WA, Forget PP. The neonatal development of intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes in the murine small intestine. Dev Immunol. 1997;5:121–128. doi: 10.1155/1997/34891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Umesaki Y, Setoyama H, Matsumoto S, Okada Y. Expansion of αβ T-cell receptor-bearing intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes after microbial colonization in germ-free mice and its independence from thymus. Immunology. 1993;79:32–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Latthe M, Terry L, MacDonald TT. High frequency of CD8αα homodimer-bearing T cells in human fetal intestine. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1703–1705. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaz NM, Faria AMC. Guia Incompleto de Imunobiologia: Imunologia como se o Organismo Importasse. COPMED; Belo Horizonte: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mota-Santos T, et al. Divergency in the specificity of the induction and maintenance of neonatal suppression. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:1717–1721. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200814. References 59 and 62 describe the relevance of microbial colonization for the development of different IEL populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira P, et al. Autonomous activation of B and T cells in antigen-free mice. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:685–688. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hashimoto K, Handa H, Umehara K, Sasaki S. Germfree mice reared on an “antigen-free” diet. Lab Anim Sci. 1978;28:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menezes JS, et al. Stimulation by food proteins plays a critical role in the maturation of the immune system. Int Immunol. 2003;15:447–455. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Staton TL, et al. CD8+ recent thymic emigrants home to and efficiently repopulate the small intestine epithelium. Nature Immunol. 2006;7:482–488. doi: 10.1038/ni1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grueter B, et al. Runx3 regulates integrin αE/CD103 and CD4 expression during development of CD4−/CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1694–1705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Staton TL, Johnston B, Butcher EC, Campbell DJ. Murine CD8+ recent thymic emigrants are integrin-positive and CC chemokine ligand 25 αE responsive. J Immunol. 2004;172:7282–7288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kunisawa J, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate dependence in the regulation of lymphocyte trafficking to the gut epithelium. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2335–2348. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu S, Bruce D, Froicu M, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. Failure of T cell homing, reduced CD4/CD8αα intraepithelial lymphocytes, and inflammation in the gut of vitamin D receptor KO mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20834–20839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Campbell DJ, Butcher EC. Rapid acquisition of tissue-specific homing phenotypes by CD4+ T cells activated in cutaneous or mucosal lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 2002;195:135–141. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz O, et al. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3101–3114. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bogunovic M, et al. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ginhoux F, et al. The origin and development of nonlymphoid tissue CD103+ DCs. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3115–3130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niess JH, et al. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agace WW. T-cell recruitment to the intestinal mucosa. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iwata M, et al. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mora JR, et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;424:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01726. References 77 and 78 identified a role for retinoic acid-producing DCs in promoting T cell homing to the intestine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McDermott MR, et al. Impaired intestinal localization of mesenteric lymphoblasts associated with vitamin A deficiency and protein-calorie malnutrition. Immunology. 1982;45:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hammerschmidt SI, et al. Stromal mesenteric lymph node cells are essential for the generation of gut-homing T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2483–2490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Edele F, et al. Cutting edge: instructive role of peripheral tissue cells in the imprinting of T cell homing receptor patterns. J Immunol. 2008;181:3745–3749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johansson-Lindbom B, Agace WW. Generation of gut-homing T cells and their localization to the small intestinal mucosa. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:226–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.El-Asady R, et al. TGF-β-dependent CD103 expression by CD8+ T cells promotes selective destruction of the host intestinal epithelium during graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1647–1657. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ericsson A, Svensson M, Arya A, Agace WW. CCL25/CCR9 promotes the induction and function of CD103 on intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2720–2729. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andrew DP, Rott LS, Kilshaw PJ, Butcher EC. Distribution of and integrins on thymocytes, α4β7 αEβ7 intestinal epithelial lymphocytes and peripheral lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:897–905. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Poussier P, Ning T, Banerjee D, Julius M. A unique subset of self-specific intraintestinal T cells maintains gut integrity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1491–1497. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011793. Details a protective role for CD8αα+TCRαβ+ IELs in preventing inflammation induced by conventional CD4+ T cells in a model of induced colitis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuhl AA, et al. Aggravation of intestinal inflammation by depletion/deficiency of γδ T cells in different types of IBD animal models. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:168–175. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mucida D, Cheroutre H. The many face-lifts of CD4 T helper cells. Adv Immunol. 2010;107:139–152. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381300-8.00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roberts SJ, et al. T-cell αβ+ and γδ+ deficient mice display abnormal but distinct phenotypes toward a natural, widespread infection of the intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11774–11779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Komano H, et al. Homeostatic regulation of intestinal epithelia by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6147–6151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guy-Grand D, DiSanto JP, Henchoz P, Malassis-Seris M, Vassalli P. Small bowel enteropathy: role of intraepithelial lymphocytes and of cytokines (IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF) in the induction of epithelial cell death and renewal. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:730–744. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<730::AID-IMMU730>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Boismenu R, Havran WL. Modulation of epithelial cell growth by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Science. 1994;266:1253–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.7973709. References 90–92 describe protective roles for γδ+ IELs in intestinal epithelial cell growth and turnover and epithelium homeostasis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mengel J, et al. Anti-γδ T cell antibody blocks the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance to ovalbumin in mice. Immunol Lett. 1995;48:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)02451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujihashi K, et al. γδ T cells regulate mucosally induced tolerance in a dose-dependent fashion. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1907–1916. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.12.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial γδ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14338–14343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212290499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Inagaki-Ohara K, et al. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes sustain the epithelial barrier function against Eimeria vermiformis infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5292–5301. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02024-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]