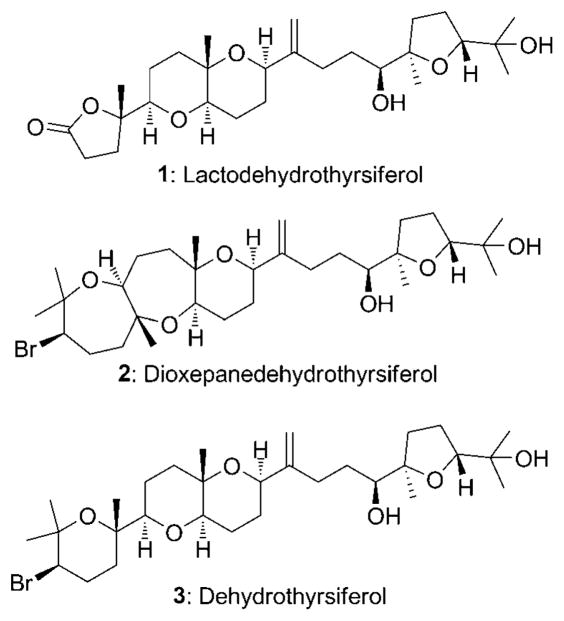

Red algae are a prolific source of squalene-derived poly-ethers[1] that show moderate to high levels of cytotoxicity[2] and very selective protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibition. [3] These unique structures (see Figure 1 for examples) have inspired total syntheses of the family members venus-atriol, [4] thyrsiferol and its esters, [4b,5] pseudodehydrothyrsiferol, [6] and dioxepanedehydrothyrsiferol, [7] in addition to subunit and analogue syntheses. [8] Our interest in this molecule class arose from our work[9] on the construction of cyclic ethers through epoxide-opening cascade reactions. [10] Lactodehydrothyrsiferol (1), isolated from the red seaweed Laurencia viridis found near the Canary Islands, [11] attracted our attention because of its unique butyrolactone group and the challenges associated with applying an epoxide-opening cascade to construct the tetrahydropyran subunits. Herein, we report the first total synthesis of 1. The sequence features an oxidatively initiated cascade reaction, a stereodivergent diene double epoxidation reaction, a diastereoselective fragment coupling through a Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi reaction, and a selective monodeoxygenation of a triol.

Figure 1.

Squalene-derived ethers from red algae.

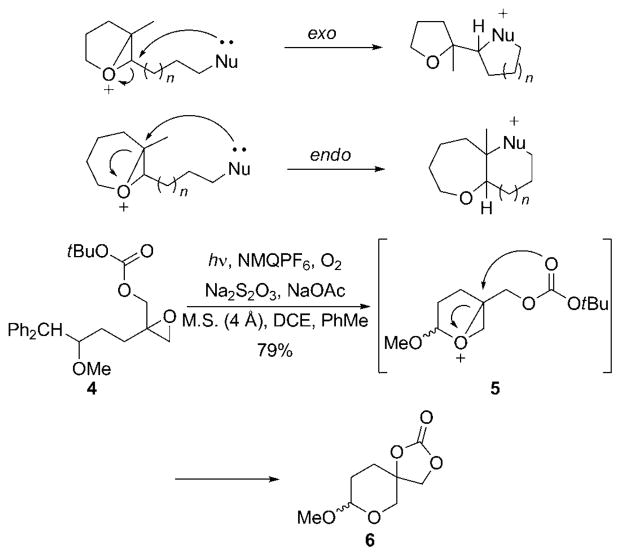

We envisioned the construction of the polycyclic subunit of 1 through a cascade reaction that would be initiated by epoxide alkylation by an oxidatively generated oxocarbenium ion. [12] The resulting epoxonium ion can be opened by an appended nucleophile, such as an epoxide (to continue the cascade) or an alkyl carbonate (to terminate the cascade). Implementation of this strategy is complicated by the kinetic regioselectivity of intramolecular nucleophilic epoxoniumion-opening reactions. We have shown[9c] that intramolecular additions to bicyclo [3.1.0] epoxonium ions proceed preferentially through an exo pathway to provide tetrahydrofurans, while bicyclo [4.1.0] epoxonium ions react through an endo pathway to yield oxepanes (Scheme 1). Our solution to the tetrahydropyran synthesis was based on the work of McDonald and co-workers, in which spirocyclization reactions are used to dictate the regioselectivity of the epoxonium-ion opening. [13] We tested this strategy under oxidative conditions by irradiating (medium pressure mercury lamp, Pyrex filter) homobenzylic ether 4 in the presence of the single-electron oxidant N-methylquinolinium hexafluorophosphate and air. [14] This led to the oxidative cleavage of the benzylic carbon–carbon bond, thus forming an oxocarbenium ion that reacts with the epoxide group to yield epoxonium ion 5. Nucleophilic addition by the carbonate group with subsequent loss of the tert-butyl cation provided spirocycle 6 in 79% yield. [15]

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of oxygen-containing heterocycles through epoxonium-ion opening. DCE =1,2-dichloroethane, M.S. =molecular sieves, NMQPF6 = N-methylquinolinium hexafluorophosphate.

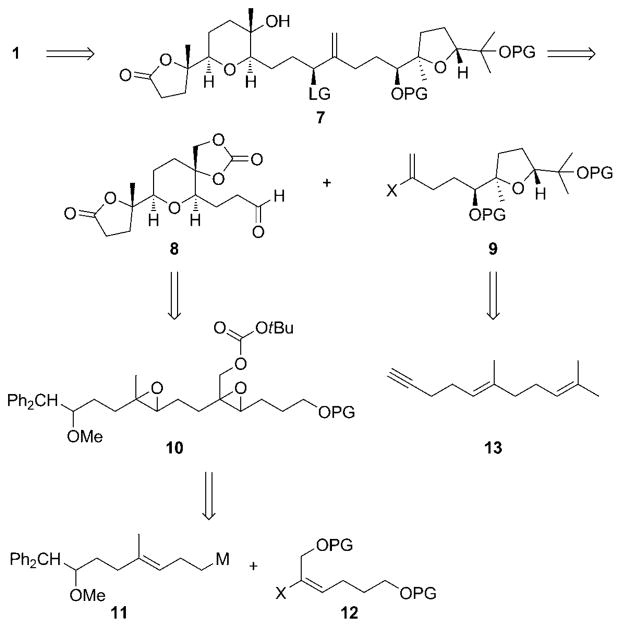

This result allowed us to propose that the synthesis of 1 could proceed through 7 (Scheme 2). This precursor will be derived from fragments 8 and 9. Fragment 8 can be accessed through a cascade of epoxide-opening reactions involving diepoxide 10, which can be prepared from a metal-mediated coupling of alkenes 11 and 12. Subunit 9 can be prepared through oxidative transformations on geranylpropyne 13.

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthesis of 1. LG =leaving group, M =metal, PG =protecting group.

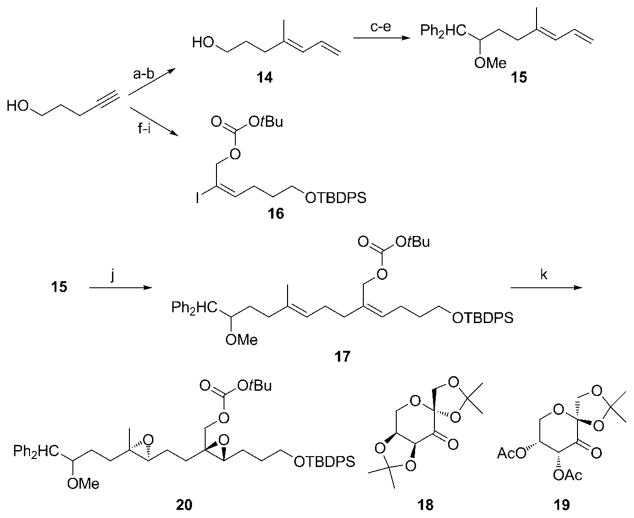

The synthesis of the diepoxide precursor 20 for the cyclization reaction is shown in Scheme 3. Methylalumination and iodination of 4-pentyn-1-ol according to the Wipf variant[16] of Negishi3s protocol[17] with subsequent palladium-mediated coupling using vinylmagnesium bromide[18] provided diene 14. While 14 could be prepared in a single operation by coupling the vinylalane intermediate directly with vinyl bromide, the two-step protocol proved to be substantially more efficient. Oxidation, diphenylmethyl-lithium addition, and methylation provided fragment 15. The diphenylmethyl group was selected because of its accessibility and high reactivity[19] in oxidative cleavage reactions. Fragment 16 was prepared through a straightforward sequence from 4-pentyn-1-ol, and a palladium-mediated hydrostannylation/iodination[20] served as the key step. Coupling the fragments through a Suzuki reaction[21] proved to be quite challenging. Hydroboration of 15 required the use of the 9-BBN dimer to form an alkylborane that showed reproducible reactivity. Catalyzing the coupling reaction with [Pd-(PPh3)4] at room temperature resulted in a slow reaction, in which 16 decomposed by the loss of the carbonate, and 15 was regenerated, presumably through a β-hydride elimination. Elevating the temperature caused alkene isomerization. Success was finally achieved by using [Pd(PtBu3)2], a catalyst that was shown by Fu and co-workers to be effective for Suzuki reactions with aryl boronic acids, [22] to yield 17 in 74% yield with no carbonate loss or β-hydride elimination. The double epoxidation reaction of 17 was complicated by the need to oxidize each alkene with opposite stereochemical control. We solved this problem by exploiting the differential reactivity of the two alkenes that arises from the inductive deactivation by the allylic carbonate group. This allowed us to use the less-reactive, first-generation, sorbose-derived Shi catalyst 18[23] to effect the epoxidation of the more reactive alkene. Upon completion of this reaction the more-reactive pseudoenantiomeric fructose-derived second-generation Shi catalyst 19[24] was added to promote the oxidation of the allylic carbonate. This sequence resulted in the isolation of diepoxide 20 in 82% yield. Although we were unable to determine the diastereoselectivity of this reaction precisely, we saw only two diastereomers by 13C NMR spectroscopy (no attempt was made to control the stereochemical orientation at the homobenzylic site). Through the synthesis of a derivative[25] we showed that the product was a single enantiomer, within the limits of NMR detection.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the cascade cyclization substrate. Reagents and conditions: a) Me3Al, Cp2ZrCl2, H2O, DCE, then I2, 94%; b) CH2=CHMgBr, [Pd(PPh3)4], PhMe, 91%; c) Oxalyl chloride, DMSO, CH2Cl2, Et3N, −78 °C; d) Ph2CH2, nBuLi, THF, 82% (two steps); e) NaH, DMF, then MeI, 96%; f) TBDPSCl, imidazole, DMF, 100%; g) nBuLi, THF, then (CH2O)n, 94%; h) Bu3SnH, [Pd(PPh3)4], C6H6, then I2, CH2Cl2,83%; i) (Boc)2O, N-methylimidazole, PhMe, 99%; j) 9-BBN dimer, THF, then 16, [Pd(PtBu3)2], K3PO4, H2O, PhMe, 74%; k) Oxone, 18, K2CO3, Bu4NHSO4, CH3CN, H2O, then 19, 82 %. 9-BBN = 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1] nonane, Boc =tert-butyloxycarbonyl, DMF =N,N′-dimethylformamide, DMSO=dimethyl sulfoxide, TBDPS =tert-butyldiphenylsilyl, THF =tetrahydrofuran.

The key cascade cyclization of 20 (Scheme 4) proceeded under the standard reaction conditions that were described in Scheme 1 to provide 21 in 45% yield upon isolation (75% yield based on recovered starting material). This reaction stalled prior to the complete consumption of the starting material and did not proceed further even after the addition of more catalyst. The reason for this is not clear, but control reactions show that benzophenone, a triplet-sensitizing product that is formed in the oxidative cleavage reaction, does not inhibit the reaction. However, the unreacted diepoxide can be resubjected to the reaction conditions to access gram quantities of 21. The synthesis of 8 was completed by a one-pot lactone formation/silyl ether cleavage using mCPBA and Sc(OTf)3, [26] with subsequent alcohol oxidation using IBX. [27] No diastereomers were isolated in this sequence, thus indicating that diastereocontrol in the diepoxidation reaction was high.

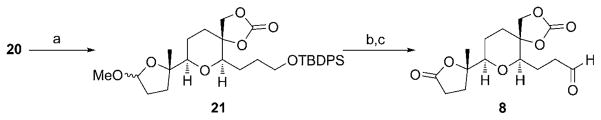

Scheme 4.

Completion of the left-hand fragment. Reagents and conditions: a) hv, NMQPF6, O2, Na2S2O3, NaOAc, DCE, PhMe, 45% yield of isolated product (75% based on recovered starting material); b) mCPBA, Sc(OTf)3, CH2Cl2, 68%; c) IBX, DMSO, 93%. IBX = 2-iodoxybenzoic acid, mCPBA=meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, Tf =tri-fluoromethanesulfonyl.

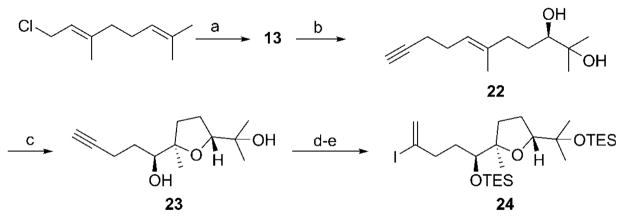

The right-hand fragment of 1 was prepared (Scheme 5) through the addition of lithiated trimethylsilylpropyne[28] to geranyl chloride with a subsequent desilylative work-up to yield 13. Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation[29] of the dimethyl-substituted alkene was highly enantioselective[25] and moderately regioselective, and provided 22 in 53% yield. A Shi epoxidation using catalyst 18 and subsequent treatment with pyridinium camphorsulfonate provided tetrahydrofuran 23 as a 13:1 mixture of diastereomers. [25] The diastereomers were readily separated by MPLC methods and the minor stereoisomer was shown to arise from imperfect stereocontrol in the epoxidation step. [25] Silyl ether formation proceeded under standard reaction conditions, and then hydrosilylation under Trost3s protocol[30] with subsequent iodination resulted in the formation of vinyl iodide 24 in 82% yield for the one-pot process.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of the right-hand fragment. Reagents and conditions: a) 1-Trimethylsilylpropyne, nBuLi, THF, −78°C, then Bu4NF, 88%; b) AD-Mix β, CH3SO2NH2, tBuOH, H2O, 53 %; c) 18, Oxone, K2CO3, Bu4NHSO4, CH3CN, H2O, then Py·CSA, 83%, d. r. = 13:1; d) TESCl, imidazole, DMAP, DMF, 89%; e) Et3SiH, [CpRu-(NCCH3)3]PF6, CH2Cl2, then I2, 2,6-lutidine, 82%. Cp = cyclopentadienyl, DMAP =4-dimethylaminopyridine, Py·CSA=pyridinium camphorsulfonate, TES =triethylsilyl.

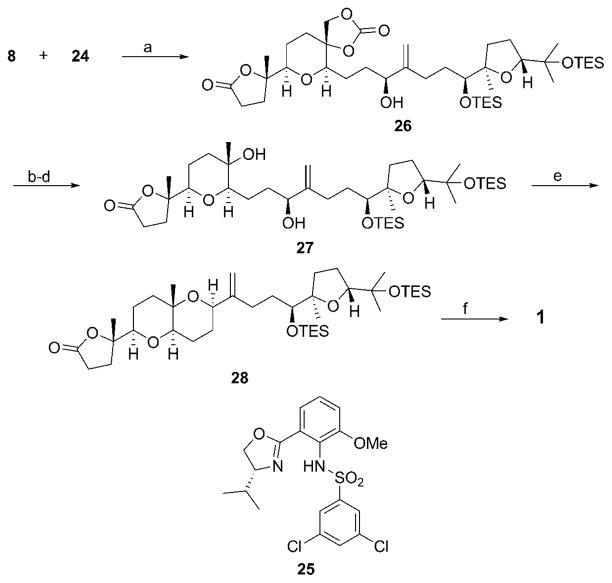

The completion of the synthesis (Scheme 6) commenced with the union of 8 and 24 through a reagent-controlled diastereoselective Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi coupling[31] using ligand 25, to form allylic alcohol 26 in 84% yield as an 8:1 mixture of diastereomers. [25] The cyclic carbonate was converted into diol 27 through methanolysis, selective tosylation of the primary alcohol of the resulting triol by the Lilly protocol[32] (at which point a single diastereomer could be isolated), and reduction with NaBH4 in warm HMPA. [33] The final ring closure was conducted by exposing 27 to the Tsunoda dehydration reagent (Me3P=C(H)CN), [34] a step that is analogous to the endgame of the synthesis of pseudodehydrothyrsiferol reported by Hioki et al. [6] This led to the formation of 28 in 40% yield. Silyl ether cleavage by Bu4NF resulted in the isolation of 1. All spectral data for synthetic 1 matched the values that were reported for the natural product. [11]

Scheme 6.

Completion of the synthesis. Reagents and conditions: a) CrCl2, NiCl2·DMP, 25, Proton Sponge, Mn, Cp2ZrCl2, LiCl, CH3CN, 84%, d. r. =8:1; b) K2CO3, MeOH, 91%; c) TsCl, Et3N, Bu2SnO, CH2Cl2, 92%; d) NaBH4, HMPA, 50 °C, 76 %; e) Me3P=C(H)CN, C6H6, 80 °C, 40%; f) Bu4NF, THF, 77 %. DMP = 2,9-dimethylphenanthroline, HMPA =hexamethylphosphoramide.

We have reported the first total synthesis of lactodehydrothyrsiferol, the longest linear sequence of which is a 16 step route. This is the shortest route that has yet been reported for any member of this molecule class. The route featured an epoxide-opening cascade cyclization to prepare the tetrahydrofuran subunit and one tetrahydropyran ring. Other notable transformations include a Suzuki coupling that employed an iodinated allylic carbonate, a diepoxidation reaction that exploited the differential reactivities of the alkenes and two pseudoenantiomeric catalysts to achieve the desired stereochemical outcome, an efficient and mild one-pot transformation of an alkyne to a vinyl iodide through hydrosilylation chemistry, a diastereoselective Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi reaction for complex fragment coupling, and a selective sequence for the deoxygenation of a single hydroxy group from a triol. The modular nature of the synthesis and the reliance upon reagent control to establish the stereocenters makes this sequence well suited for the construction of analogues that can be used to test hypotheses regarding the structure–activity relationships of this interesting class of PP2A inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank the National Institutes of Health, Institute of General Medicine (GM062924) for generous support of this work. We thank Prof. José Fernández (Universidad de La Laguna) for copies of the spectra for lactodehydrothyrsiferol.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201007757.

References

- 1.Fernández JJ, Souto ML, Norte M. Nat Prod Rep. 2000;17:235. doi: 10.1039/a909496b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Fernández JJ, Souto ML, Norte M. Bioorg Med Chem. 1998;6:2237. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pec MK, Aguirre A, Moser-Their K, Fernández JJ, Souto ML, Dorta J, Diáz-González F, Villar J. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1451. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Matsuzawa S, Suzuki T, Suzuki M, Matsuda A, Kawamura T, Mizuno Y, Kikuchi K. FEBS Lett. 1994;356:272. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Souto ML, Manríquez CP, Norte M, Leira F, Fernández JJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1261. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Corey EJ, Ha DC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:3171. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(88)85122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hashimoto M, Kan T, Nozaki K, Yanagiya M, Shirahama H, Matsumoto T. J Org Chem. 1990;55:5088. [Google Scholar]

- 5.González IC, Forsyth CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9099. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hioki H, Motosue M, Mizutani Y, Noda A, Shimoda T, Kubo M, Harada K, Fukuyama Y, Kodama M. Org Lett. 2009;11:579. doi: 10.1021/ol802600n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanuwidjaja J, Ng S-S, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12084. doi: 10.1021/ja9052366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) McDonald FE, Wei X. Org Lett. 2002;4:593. doi: 10.1021/ol0171968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nishiguchi GA, Graham J, Bouraoui A, Jacobs RS, Little RD. J Org Chem. 2006;71:5936. doi: 10.1021/jo060519z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Kumar VS, Aubele DL, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2002;4:2489. doi: 10.1021/ol0261074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kumar VS, Wan S, Aubele DL, Floreancig PE. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3570. [Google Scholar]; c) Wan S, Gunaydin H, Houk KN, Floreancig PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7915. doi: 10.1021/ja0709674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For reviews and recent examples from other research groups, see: Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:763. doi: 10.3390/md8030763.Morten CJ, Byers JA, Van Dyke AR, Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3175. doi: 10.1039/b816697h.Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Angew Chem. 2009;121:5352. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900600.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5250.Boone MA, Tong R, McDonald FE, Lense S, Cao R, Hardcastle KI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5300. doi: 10.1021/ja1006806.Van Dyke AR, Jamison TF. Angew Chem. 2009;121:4494. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900924.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4430.Tong R, McDonald FE. Angew Chem. 2008;120:4449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800749.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4377.Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Science. 2007;317:1189. doi: 10.1126/science.1146421.Morimoto Y, Yata H, Nishikawa Y. Angew Chem. 2007;119:6601. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701737.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:6481.Simpson GL, Heffron TP, Merino E, Jamison TF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1056. doi: 10.1021/ja057973p.Marshall JA, Mikowski AM. Org Lett. 2006;8:4375. doi: 10.1021/ol061826u.Valentine JC, McDonald FE, Neiwart WA, Hardcastle KI. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4586. doi: 10.1021/ja050013i.Zakarian A, Batch A, Holton RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7822. doi: 10.1021/ja029225v.Xiong Z, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9328.

- 11.Souto ML, Manríquez CP, Norte M, Fernández JJ. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:8119. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Kumar VS, Floreancig PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3842. doi: 10.1021/ja015526d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Floreancig PE. Synlett. 2007:191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) McDonald FE, Bravo F, Wang X, Wei X, Toganoh M, Rodríguez JR, Do B, Neiwert WA, Hardcastle KI. J Org Chem. 2002;67:2515. doi: 10.1021/jo0110092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tong R, McDonald FE, Fang X, Hardcastle KI. Synthesis. 2007:2337. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar VS, Aubele DL, Floreancig PE. Org Lett. 2001;3:4123. doi: 10.1021/ol016996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For alternative methods of tetrahydropyran formation through epoxonium-ion opening, see: Bravo F, McDonald FE, Neiwert WA, Do B, Hardcastle KI. Org Lett. 2003;5:2123. doi: 10.1021/ol034539o.Morimoto Y, Nishikawa Y, Ueba C, Tanaka T. Angew Chem. 2006;118:824. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503143.Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:810.

- 16.Wipf P, Lim S. Angew Chem. 1993;105:1095. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:1068. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Horne DE, Ei Negishi jt. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2252. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamao K, Sumitani K, Kumada M. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:4374. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Seiders JR, II, Wang L, Floreancig PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:2406. doi: 10.1021/ja029139v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang L, SeidersII JR, Floreancig PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12596. doi: 10.1021/ja046125b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang HX, Guib3 F, Balavoine G. J Org Chem. 1990;55:1857. [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Miyaura N, Ishiyama T, Sasaki H, Ishikawa M, Satoh M, Suzuki A. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:314. [Google Scholar]; b) Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem. 2001;113:4676. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4544::aid-anie4544>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4544. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Littke AF, Fu GC. Angew Chem. 1998;110:3586. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:3387. [Google Scholar]; b) Littke AF, Dai C, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Wang Z, Tu Y, Frohn M, Zhang J, Shi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11224. [Google Scholar]; b) Xiao MX, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2006;71:5377. doi: 10.1021/jo060335k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Wang B, Wu XY, Wong OA, Nettles B, Zhao MX, Chen D, Shi Y. J Org Chem. 2009;74:3986. doi: 10.1021/jo900330n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nieto N, Molas P, Benet-Buchholz J, Vidal-Ferran A. J Org Chem. 2005;70:10143. doi: 10.1021/jo051682h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Please see the Supporting Information for detailed schemes related to stereochemical analysis.

- 26.Grieco PA, Oguri T, Yokoyama Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:419. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frigerio M, Santagostino M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:8019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipshutz BH, Bulow G, Fernandez-Lazaro F, Kim S, Lowe R, Mollard P, Stevens KL. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:11664. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolb HC, Van Nieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2483. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trost BM, Ball ZT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17644. doi: 10.1021/ja0528580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo H, Dong C, Kim D, Urabe D, Wang J, Kim JT, Liu X, Sasaki T, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15387. doi: 10.1021/ja905843e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinelli MJ, Nayyar NK, Moher ED, Dhokte UP, Pawlak JM, Vaidyanathan R. Org Lett. 1999;1:447. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutchins RO, Kandasamy D, Dux F, III, Maryanoff CA, Rotstein D, Goldsmith B, Burgoyne W, Cistone F, Dalessandro J, Pulgis J. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2259. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto I, Kaku H, Tsunoda T. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:474. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.