Abstract

A retained surgical item is a surgical patient safety problem. Early reports have focused on the epidemiology of retained-item cases and the identification of patient risk factors for retention. We now know that retention has very little to do with patient characteristics and everything to do with operating room culture. It is a perception that minimally invasive procedures are safer with regard to the risk of retention. Minimally invasive surgery is still an operation where an incision is made and surgical tools are placed inside of patients, so these cases are not immune to the problem of inadvertent retention. Retained surgical items occur because of problems with multi-stakeholder operating room practices and problems in communication. The prevention of retained surgical items will therefore require practice change, knowledge, and shared information between all perioperative personnel.

Introduction

Even though small incisions are made and few surgical items are used, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) cases are not immune to the problem of inadvertent surgical item retention. In the US and the UK, unintended retention of a surgical item in a patient after surgery is a reportable event [1, 2]. Retained surgical item (RSI) is now the preferred term (rather than retained foreign body or object) because foreign bodies can be any object found or left in a patient, e.g., bullets, coins, bottles, and shrapnel [3]. RSI refers specifically to the surgical material (tools, supplies, and equipment) that is used by surgical providers to heal, but when inadvertently left in patients, can cause harm [4]. An RSI is a surgical patient safety problem [5].

The minimal requirements for retention are a case in which an incision is made and surgical items are used inside the patient. This is true for all four classes of surgical items, i.e., sponges, needles, instruments, and miscellaneous small objects which must be accounted for before the patient leaves the operating or procedure room [6]. RSI cases have been reported from around the world for decades, and surgical paraphernalia have been left in practically every body cavity after any kind of case [7–9]. While reports in the early 2000s indicated there were patient-specific (obesity) and case-specific characteristics (emergencies) that increased the risk of retention [10–12], we now know that retention has very little to do with specific patients or the time of an operation and everything to do with the operating room culture and environment in which the patient has the operation [13–15]. For example, more retained sponge cases occur in ordinary elective surgery cases. Retention has occurred in cases where only ten sponges were used, the surgical counts were performed, and the final count was called correct. When a sponge or item is recognized as missing (the final count was called incorrect) yet the patient leaves the OR with the item still inside occurs in the minority of cases.

NoThing Left Behind® is a voluntary surgical patient safety initiative started in 2004 to understand why retained surgical items are such a persistent problem and to develop practices to ensure RSI become a “never happen event” [5]. Hospitals have voluntarily participated with data sharing, development, and implementation of safer multidisciplinary practices. In spite of the specific operative practice of counting, which is designed to minimize the chance of retention, RSI cases still occur. Surgeons, nurses, surgical technologists, radiologists, radiology technologists, and anesthesiologists have come to rely on and place trust in the surgical count to the exclusion of additional safety actions and adoption of different perspectives about the problem. Most practitioners minimize the risk that they will be involved in an RSI case and fail to recognize that current manual counting practices are not sufficiently reliable. There is hope that with surgical culture change, implementation of reliable manual practices, and, when needed at least for surgical sponges, new technological adjuncts, the problem will be solved.

It is estimated that there are 1500-2000 retained surgical item cases a year in the US. To some this rate may seem high since they may not have had an event in their facility, but every surgeon either knows someone who has had a retained item event or has personally had to address the problem of miscounts in the OR. There are over 6,000 hospitals with operating and procedure rooms in the US. There are no data, other than individual case reports, on the frequency of retention in hospitals around the world, but every year more than 45 million inpatient procedures are performed in the US and 234 million operations are performed globally [16, 17]. These cases present opportunities for retention. Minimally invasive approaches are used in many operations and events of retention have been reported [18–20]. It is clear that all hospitals do not have the same degree of exposure to this problem as there are facilities that have not had a retained sponge case in over 10 years while others have had one event almost every quarter.

In most reported series, retained sponges are the most common surgical item left in patients and therefore we have the most information about why these cases occur. In over 80% of retained sponge cases the surgical counts were called correct at the conclusion of the case [7, 10]. Then hours, days, months, or years later the patient developed symptoms or the retained item was discovered on an incidental X-ray. These cases are always a surprise [14]. After an event occurs, hospital clinical staff and risk management teams assemble to conduct root cause and focused review analyses. Often the results of these reviews identify that the surgeon did a “sweep,” surgical counts were performed, and even mandatory X-rays were taken but no one is sure when or how retention took place [21]. It has been difficult to identify the specific practice error so remedies for prevention have historically been to review and revise policies or add an additional step to an already complex counting process.

It is thought that because few sponges are used intracorporeally during an MIS procedure the risk of retention will be lower in MIS cases. This is not true, however, because there is no relationship between the number of items used during a case and the risk of retention. Hundreds of instruments are frequently used during cases yet retained instruments are exceedingly rare and the instrument most commonly retained is a malleable or ribbon-type retractor. To some it seems unbelievable that in a case in which only ten sponges are used one could be retained, but this fact illustrates well that it is not that the nurses and surgical technologists have not counted but that they have not employed a reliable practice of counting and that surgeons have not explored operative sites carefully to do their best to remove all items. If intraoperative X-rays have been obtained, the radiology technologists have taken incomplete or inadequate films that have not been read by radiologists who are the content experts on image interpretation. Multiple stakeholders have usually contributed to the errors.

It has been suggested that the incidence of RSI will fall with increasing numbers of laparoscopic and MIS procedures being performed [22]. However, if one understands why RSI cases occur, it is not certain that this should be true. RSI cases occur because of problems with knowledge and communication among all perioperative personnel and the failures of their specific intraoperative practices. Unless there are changes in surgeon and nursing practices and behaviors in the OR there will be retained surgical items during laparoscopic or minimally invasive procedures.

Case examples

Incident reports, focused reviews, and root cause analyses from October 2004 to the present from hospitals that have voluntarily shared data elements of their cases of RSI have been reviewed. Four selected cases of retained sponges after MIS substantiate some of the above points.

Case 1

A patient underwent a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication during which ten raytex (acronym for 4-in. × 4-in. radiopaque textile) sponges were counted in, some of which were used inside the patient during the case primarily as an aid to dissection. At the end of the case the final sponge count was documented as correct. The patient had no subsequent operations. Four years later at another facility the patient underwent a CT of the abdomen because of abdominal pain. This revealed a raytex sponge in the midabdomen interspersed between loops of small bowel. A laparotomy was performed to remove the raytex sponge which was walled off and densely adherent to the surrounding bowel.

Case 2

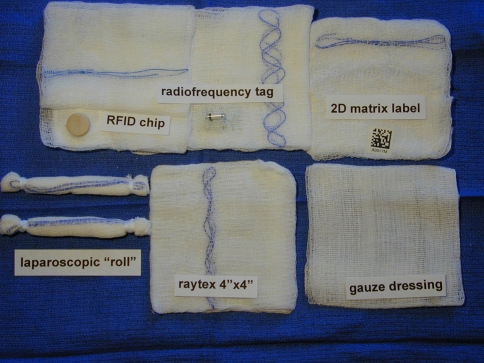

A patient underwent a thoracoscopic Heller myotomy. Laparoscopic roll sponges were used during the case (Fig. 1). At the end of the case the final sponge count was documented as correct. Postoperatively, the patient developed respiratory distress and required reintubation. A routine postintubation chest X-ray revealed a laparoscopic roll in the apex of the left chest. The patient went back to the OR and the roll sponge was removed thoracoscopically.

Fig. 1.

MIS sponges: Gauze dressing sponge without radiopaque marker, radiopaque 4-in. × 4-in. gauze sponge (“raytex”), laparoscopic 0.5-in. × 4-in. roll, and the three types of new technology gauze sponges

Case 3

A patient underwent a laparoscopy-assisted sigmoid colectomy. Twenty lap pads were used during the open part of the case. At the end of the case the final sponge count was documented as correct. On the fifth postoperative day the patient developed fever and persistent ileus. An abdominal CT showed a retained lap pad with a large abscess in the right lower quadrant. A laparotomy was performed to remove the lap, irrigate the area, and place a closed suction drain.

Case 4

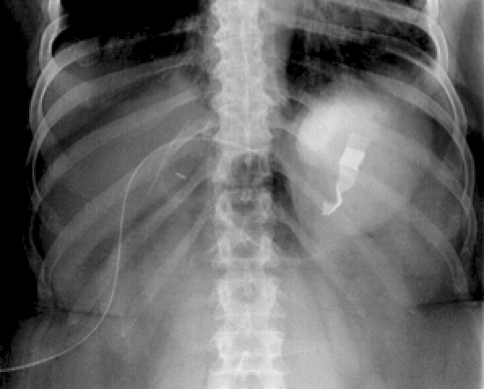

A patient underwent laparoscopic lysis of adhesions for a small-bowel obstruction. Ten raytex sponges were opened during the case. Hanging sponge counters were used. At the end of the case the final sponge count was documented as correct. The patient also had ureteral stents in place and in the postoperative period underwent at least two abdominal X-rays related to stent placement. On a third abdominal film, coincidentally read by a cross-covering radiologist, a raytex sponge was found in the pelvis (Fig. 2). The raytex was present on review of the previous films. The patient was in hospice care for underlying disease. The retained raytex sponge was disclosed to the family but they decided not to have it removed.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal X-ray of retained raytex 4-in. × 4-in. sponge in pelvis after laparoscopic lysis of adhesions for small-bowel obstruction

Discussion

Practice change and action plans

These cases illustrate the requirement for multi-stakeholder participation in any effort to prevent RSI. In all four of these cases the final sponge count was correct yet a retained sponge was subsequently found. The perioperative staff counted the sponges and most likely, based on current AORN-recommended practices, they counted the sponges multiple times during the case; however, they had no reliable system in place to verify where all the sponges were at the end of the case and to properly account for them. That is, they counted them but they were not accounted for. This is a problem with the practice of how nurses and surgical technologists count sponges [23–26].

To address this concern we have been working with hospitals on the implementation of a reliable manual sponge management practice called Sponge ACCOUNTing that was designed using information from studies about where existing sponge-counting practices went wrong. The system requires a wall-mounted dry erase board in every OR and blue-backed hanging plastic sponge holders with standard-issue radiopaque surgical sponges. Current practices that use plastic hanging “counters” (as mentioned in the fourth case) use them as another place to deposit the sponges; they also usually have two systems in place: one for counting raytex and one for counting laps. Sponge ACCOUNTing includes standardized methods for nurses and surgical technologists to use when counting the sponges (“see, separate, and say”), requires all sponges be managed in groups of ten, has a standardized format for recording the counts, and requires that all sponges are in the pockets of the sponge holders at the final count (“no empty pockets”). This steps are taken so that at the final count all sponges (used and unused) will be in one place, available for everyone in the OR to easily view, and, therefore, it will be highly unlikely that one can remain in the patient. There are associated surgeon, radiologist, and anesthesiologist safe practices to complete the multi-stakeholder effort [5]. At the current time, 97% of hospital operating rooms evaluating this system have had no retained sponges for at least 1 year.

During the operative procedure surgeons will ask for and insert various objects intracorporeally. If sponges are required during the MIS part of the procedure, raytex sponges are rolled up and inserted down trocars. Laparoscopic roll sponges (1/2-in. × 4-in. gauze rolls), which have been designed to go easily through trocars, are also used (Fig. 1). During the open portion of an MIS operation, the surgeon uses lap pads for packing away viscera to facilitate exposure through the smaller incision. If the surgeon puts these items in the patient there must be a practice in place to perform a methodical wound exam to find and remove the items before wound closure begins [27]. In an MIS case, this process should be performed before the camera is removed in conjunction with the closing item counts. In the cases presented above, there was no information given about surgeon-specific practices. A wound exam should be performed not only of the exact operative site but also in areas where sponges could have been placed. In the third case, the operative site was in the left lower quadrant but the errant sponge was found in the right lower quadrant and was likely a sponge used for retraction or packing.

During MIS, surgeons also insert and use devices that can have multiple parts, some of which are not radiopaque. Manufacturers cannot always place a radiopaque marker on plastic or rubber items, so when these multipart devices are removed it is the job of the surgical technologist to recognize that a part may be missing and speak up so a search can be undertaken. It is important for the surgical team to have a transparent system in place to help track items since memory alone is a weak forcing function. The method of just trying to remember when something was placed or where it was placed is doomed to failure. Writing it down on the back table or on the dry erase board is a stronger practice. We have some practice recommendations for prevention of RSI in MIS cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

MIS-specific team-based activities to prevent RSI

| Place only surgical items that have radiopaque markers intracorporally |

| Nurses should “see, SEPARATE and say” sponges during the counting-in practice |

| Perform a methodical wound exam using graspers and thoughtful exploration BEFORE camera removal while nurses perform closing sponge, sharps and small-item counts |

| Use a transparent and verifiable practice at the final count to see that all items have been accounted for |

| Empower surgical technologists to be the content experts on surgical instruments and devices |

| Ensure that anyone can speak up immediately if something is missing or is of concern |

| Help the radiology technologist obtain complete high-quality views of the wound |

| Tell the radiologist specifically what item is missing |

X-rays obtained intraoperatively or postoperatively should be reviewed by radiologists, but they also make errors when it comes to recognizing RSI. Radiologists need to know what the surgical items look like on a radiographic image, need to communicate to radiology technologists about the adequacy of the images taken, and need to communicate with surgeons about their findings [28–30]. Radiologists need to use caution in assuming that an obvious radiopaque density seen on a film is a known piece of surgical equipment (e.g., mistaking the radiopaque laparotomy pad marker for a Penrose drain; Fig. 3). Radiologists can miss what appear to be obvious findings that often a “new set of eyes” will make the discovery, as happened in the fourth case. Good communication between radiologists and surgeons is important. These examples should make it clear that an RSI occurs not because of the mistake of one person but as a result of a concatenation of errors that are usually a product of poor surgical practices and inadequate knowledge and communication.

Fig. 3.

Abdominal X-ray of retained laparotomy pad in left upper quadrant. This film was mistakenly read as “Penrose drain present in left upper quadrant” by radiologist

To complete the discussion, mention needs to be made of surgical needles of various sizes that are used routinely during MIS cases and can be dropped or lost. Small needles (<15 mm) can be difficult to find and have not been reported to cause injury in large body cavities. Larger lost or broken needles have been reported to cause pain and psychological discomfort and various methods have been explored to aid in their identification and removal [20, 31, 32].

Instruments are usually counted before the operation begins using the standardized count sheets sent with the instrument trays [6]. Frequently, multiple instruments are opened during surgery and counting and tracking them all is time consuming and probably error prone, so hospitals have developed exceptions to the general requirement of counting all instruments. Exceptions have been made based on the size of the instrument in relation to the wound or the size of the patient. These exceptions have often excluded the counting of MIS instruments that are too large to be left in the wound and would be removed from the field if the case progressed to open. Final counts of sponges, needles, instruments, and small miscellaneous items should be documented separately in the operative record since a case can have an incorrect needle final count (missing a small needle) but correct counts for the other classes of items. Sponges, needles, and small miscellaneous objects can be retained inside the patient and their chance of retention is not based upon the size of the wound; thus, they should be accounted for in all cases.

Removal of a retained surgical item

Retained surgical instruments, i.e., whole complete surgical instruments such as a pair of scissors or a clamp, are extremely rare in open surgical cases. The most frequently reported retained instrument is a malleable or ribbon retractor. Because a small incision is used in MIS cases, a large instrument could not fit into the surgical wound so retention of the large instruments does not occur. What is a more common is the use of an MIS approach to remove retained surgical items that were left in the patient after an open operative procedure.

There have been about ten publicly reported cases of a retained malleable retractor, most of which were reported in the newspaper or lay press [7]. These cases attract great public interest and general consternation as to how such an event can occur. A retained malleable retractor usually results from two process errors on the part of the surgical team. The first is a loss of focus on the whereabouts of the retractor and the second is a failure in the instrument count. These retractors have been left in patients for days to years, and because they are stainless steel they undergo very little degeneration. They do induce a fibrotic or mild inflammatory response such that the omentum has been found wrapped around the retractor.

There have been two reports of laparoscopic removal of a retained ribbon retractor [33, 34] that was left after an open intra-abdominal procedure. In one case the retractor was discovered 14 years after the initial operation. In both cases the retractor was easily removed. From this limited experience it is reasonable to conclude that instruments may be removed laparoscopically because they do not induce much of an inflammatory reaction. It is not unreasonable to try a minimally invasive approach first.

It is less clear what to do in the case of a retained surgical sponge. Retained surgical sponges usually present in one of two ways. First, if the sponge has become infected or induces a robust inflammatory response that leads to abscess formation, the patient is usually symptomatic and a CT scan is obtained. These cases often present within days to weeks after the initial operation. It has been a common practice to perform a laparotomy to remove the retained sponge in the setting of infection because of the possible need to perform a bowel resection and dissection of the sponge from the intertwined bowel loops. There have been a number of published reports on the laparoscopic removal of an offending sponge and successful management of the abscess, although these cases did not involve any resection [35–38]. These successful cases have all occurred when the retained sponge was discovered within 2 weeks of the operation. Another indication for MIS success in retained sponge removal is in those cases in which an incidental X-ray in the early postoperative period has revealed the RSI, e.g., the second case mentioned above. Since there has been little time for adherence or inflammation to set in, these sponges have been able to be removed.

The second way in which a retained sponge can present is months to years after the initial operation and the sponge often presents as a mass. These sponges have induced a fibrous reaction, much like a grain of sand in an oyster, and the body has walled off the sponge. These masses have been worked up as a suspicious neoplasm and CT and MRI scans have been instrumental in establishing the correct diagnosis. In these cases, the retained sponge was removed successfully with an MIS approach [4]. There is an extensive literature on the successful use of laparoscopic and thoracoscopic approaches for the retrieval of post-traumatic and self-induced retained foreign bodies [39–42]. Within these series there have been reports of retrieval of small miscellaneous surgical items such as a ureteral stent and drain fragments. Experience with the removal of these foreign bodies can be applied to the decision on how to approach a retained surgical item. It is not unreasonable to attempt an MIS approach if the necessary expertise is available.

Technological adjuncts for sponge counts

There are three commercial systems currently available worldwide as adjuncts to a manual sponge count [43–45]. All three are in use in hospitals throughout the US. The systems are not interchangeable and once a hospital commits to one system, all the sponges used in that facility are switched to the specific new technology sponge management system. There is not much data on the success of implementation of these systems, and more importantly on the failures of these systems, but as experience is gained more reports will be forthcoming [46–49]. All three use different and distinct technological approaches and have different applications in MIS cases. The essential components of each device are a distinct type of detection element attached to a surgical sponge (Fig. 1) and a distinct compatible electronic readout system. The devices can be separated into one that can count sponges, one that can detect sponges, and one that can count and detect sponges.

Computer-assisted sponge count

This system consists of two-dimensional-matrix-labeled sponges and a scanning device that can read the labels [43]. The matrix label is scanned in with a handheld or table-mounted scanner as the sponge is put on the sterile field and then each sponge is scanned out when it removed from the table. The matrix label is embedded in each of the variable-sized surgical sponges, and each sponge has a unique identifier that enables the scanner to count different types of sponges. The sponges are counted, maintaining “line of sight” for each sponge. The placement and presence of the matrix label does not interfere with the usability of the sponges. These sponges can be rolled up and put down MIS trocars with ease. In order to account for all sponges at the final count, the sponges must be removed from the patient and individually passed under the scanner. The scanner cannot “read through” the patient and detect the presence of a matrix-labeled sponge. In the event of a missing sponge, an X-ray is used to determine if it is in the patient.

Radiofrequency detection system

This system consists of sponges that have a small passive radiofrequency tag sewn into a pocket on each sponge and a handheld wand or mat that contains the antennae and detection system [44]. The tag is 4 mm × 12 mm and is recognized as only a yes or no signal. The tag is detected when the handheld wand or mat is activated and the computer console presents a visual and audible signal that a sponge has been detected. The system does not distinguish between sponge types or number of sponges. The signal readout will be the same intensity if there are one or five sponges. The tag is small and is present on many different sponge types and does not interfere with the usability of the sponge. Sponges with these tags can be rolled up and put down 10-mm trocars. In the event of a missing sponge, the mat can be activated to determine if the sponge is in the patient or the wand can be used to wand the patient or scan the trash to find the sponge. This system does not count sponges.

Radiofrequency identification system

This system has a unique radiofrequency identification chip sewn into each sponge and a separate computer console with a scanning bucket into which used sponges are placed [45]. This passive chip is about the size of a dime, and when present on small raytex sponges, it is noticeable and too large to fit down MIS trocars. A smaller 7-mm chip has recently been made available which should fit down 10-mm trocars. There is not much experience with this new chip to know if it functions like the larger version. Each sponge has a specific identifying chip so sponges of different types pooled together can be distinguished and counted. Unopened packages of sponges are placed on a front panel of the console to be electronically counted. Then the sponges are opened and placed on the sterile field. Used sponges can be put directly into the bucket. Alternatively, they can be placed into plastic bag-lined kick buckets and the entire plastic bag full of sponges can then be placed into the scanning bucket. The sponges will all be individually counted. If there is a missing sponge it can be detected with a wand that is attached to the bucket by a long cord. When the missing sponge is found it must be added to the sponges in the bucket to reconcile the count. This device offers a complete sponge counting and detection system.

Conclusions

Ten years ago in a World Journal of Surgery review on intraperitoneal retained sponges, the authors brought attention to this unique surgical problem by pulling together the world’s literature of cases and showed readers that these events were not rare and that they were preventable [50]. They offered straightforward advice which ten years later we would consider individual vigilance actions: perform repeated sponge counts before and after each part of the operative procedure and use large radiopaque sponges one by one. These recommendations are not wrong but they reflect a predominant view of that time that through individual vigilance and individual effort retained sponges could be prevented. We now know that retained surgical items are system problems and cannot be prevented with just the effort of a single individual. System problems require system solutions, and while we still need our nursing colleagues to count sponges, we need even more for them to have in place a safe and reliable system that can account for the sponges. We need surgical technologists to know about the multiple parts of the equipment and devices we use and speak up if something is missing. We need radiology technologists to take high-quality and complete intraoperative films, and we need radiologists to interpret the images and share their findings expeditiously. We need anesthesiologists to monitor the use of the nonradiopaque sponges they use and keep the patient sedated if we need to prolong the operation a bit to find something that is missing. Most importantly we need surgeons to do their best to perform a methodical wound exam in every case before they ask for closing suture, and to create an operating room environment that promotes the exchange of knowledge and information. To ensure the safety of our surgical patients, together we must make sure there is “NoThing Left Behind.”

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.National Quality Forum website (2010) http://www.qualityforum.org. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 2.National Patient Safety Agency website (2010) http://www.npsa.nhs.uk. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 3.Flores-Suarez R, Reyes-del Valle J. A foreign body. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm0707656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Possover M. Gossypiboma in the pouch of Douglas. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:e9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm075197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NoThing Left Behind website (2010) http://www.nothingleftbehind.org. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 6.Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses (2010) Recommended practices for prevention of retained surgical items. In: Perioperative standards and recommended practices. AORN, Denver, CO. http://www.aorn.org/psrp. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 7.Gibbs VC, Coakley FD, Reines HD. Preventable errors in the operating room: retained foreign bodies after surgery–—part 1. Curr Probl Surg. 2007;44:281–337. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zantvoord Y, van der Weiden RF, van Hooff MH. Transmural migration of retained surgical sponges: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;633:465–471. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e318173538e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stawicki SP, Evans DC, Cipolla J, et al. Retained surgical foreign bodies: a comprehensive review of risks and preventive strategies. Scand J Surg. 2009;98:8–17. doi: 10.1177/145749690909800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser CW, Friedman S, Spurling KP, et al. The retained surgical sponge. Ann Surg. 1996;224:79–84. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199607000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gawande AA, Studdert DM, Orav EJ, et al. Risk factors for retained instruments and sponges after surgery. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:229–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lincourt AE, Harrell A, Cristiano J, et al. Retained foreign bodies after surgery. J Surg Res. 2007;138:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan W, Le T, Riskin L, Macario A. Improving safety in the operating room: a systematic literature review of retained surgical sponges. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:207–214. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328324f82d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McIntyre LK, Jurkovich GJ, Gunn MD, Maier RV. Gossypiboma: tales of lost sponges and lessons learned. Arch Surg. 2010;145:770–775. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cima RR, Kollengode A, Storsveen AA, et al. A multidisciplinary team approach to retained foreign objects. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN et al (2010) National hospital discharge survey: 2007 summary. No. 29, 10/26/10. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds/nhds_products.htm. Accessed 7 Nov 2010 [PubMed]

- 18.Huntington TR, Klomp GR. Retained staples as a cause of mechanical small-bowel obstruction. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:353–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00187786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendez LE, Medina C. Late complication of laparoscopic salpingoophorectomy: retained foreign body presenting as an acute abdomen. JSLS. 1997;1:79–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soyer P, Valleur P. Retained surgical needle after laparoscopic sacrocolporectopexy. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:688–690. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cima RR, Kollengode A, Garnatz J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of potential and actual retained foreign object events in surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiernan F, Joyce M, Byrnes CK, et al. Gossypiboma: a case report and review of the literature. Ir J Med Sci. 2008;177:389–391. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riley R, Manias E, Polglase A. Governing the surgical count through communication interactions: implications for patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:369–374. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Lipsitz SR, et al. The frequency and significance of discrepancies in the surgical count. Ann Surg. 2008;248:337–341. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318181c9a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson S, Brady S. Counting difficulties: retained instruments, sponges and needles. AORN J. 2008;87:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowlands A, Steeves R. Incorrect surgical counts: a qualitative analysis. AORN J. 2010;92:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs VC. Patient safety practices in the operating room: correct site surgery and nothing left behind. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:1307–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whang G, Mogel GT, Tsai J, Palmer SL. Left behind:unintentionally retained surgically placed foreign bodies and how to reduce their incidence—pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:S79–S89. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.7153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor AR, Coakley FV, Meng MV, Eberhardt S. Imaging of retained surgical sponges in the abdomen and pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:481–489. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.2.1800481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edel EM. Increasing patient safety and surgical team communication by using a count/time out board. AORN J. 2010;92:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinpeter SJ, Kline RC, Finan MA. Retained surgical needle in the perineum. Report of a case with a novel method of search and rescue. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:303–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozgun MT, Batukan C, Basbug M, Atakul T. Management of a broken needle: retained in the first caesarean section, removed during the second abdominal delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:653–655. doi: 10.1080/01443610802378355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karahasanoglu T, Unal E, Memisoglu K, et al. Laparoscopic removal of a retained surgical instrument. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2004;14:241–243. doi: 10.1089/lap.2004.14.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodrigues D, Perez NE, Hammer PM, Webber JD. Laparoscopic removal of a retained intra-abdominal ribbon malleable retractor after 14 years. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2006;16:369–371. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh R, Mathur RK, Patidar S, Tapkire R. Gossypiboma: its laparoscopic diagnosis and removal. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14:304–305. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200410000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ibrahim IM. Retained surgical sponge. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:709–710. doi: 10.1007/BF00187946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuen PM, Rogers MS, Chang AM. Laparoscopic removal of retained surgical gauze after vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;57:209–210. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Childers JM, Caplinger P. Laparoscopic retrieval of a retained surgical sponge: a case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chin EH, Hazzan D, Herron DM, Salky B. Laparoscopic retrieval of intraabdominal foreign bodies. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1457. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhansali M, Patankar S, Dobhada S. Laparoscopic management of a retained heavily encrusted ureteral stent. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1141–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bharathan R, Dexter S, Hanson M. Laparoscopic retrieval of retained Redivac drain fragment. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:263–264. doi: 10.1080/01443610902754000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutta R, Kumar A, Das CJ, Jindal T. Emergency video-assisted thoracoscopic foreign body removal and decortication of lung after chest trauma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:155–158. doi: 10.1007/s11748-009-0490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surgicount Medical website. http://www.surgicountmedical.com. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 44.RF Surgical website. http://www.RFsurg.com. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 45.Clearcount Medical website. http://www.clearcount.com. Accessed 7 Nov 2010

- 46.Macario A, Morris D, Morris S. Initial clinical evaluation of a handheld device for detecting retained surgical gauze sponges using radiofrequency identification technology. Arch Surg. 2006;141:659–662. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenberg CC, Diaz-Flores R, Lipsitz SR, et al. Bar-coding surgical sponges to improve safety: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2008;247:612–616. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656cd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cima RR, Kollengode A, Clark J, Pool S et al. (2010) Evaluation and implementation of a bar-coded sponge counting system: impact on retained sponges after one year. Presented at American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress, Washington DC, October 3–7, 2010

- 49.Rupp CC, Kim HJ, Kagarise MJ (2010) Effectiveness of radio-frequency surgical detection system to promote patient patient safety during an operative procedure by improving the process by which doctors and nurses track sponges prior to wound closure. Presented at American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress, Washington DC, October 3–7, 2010

- 50.Lauwers PR, Van Hee RH. Intraperitoneal gossypibomas: the need to count sponges. World J Surg. 2000;24:521–527. doi: 10.1007/s002689910084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]