Abstract

The role of angiogenesis in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis (TB) is not clear. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of sera from TB patients on angiogenesis induced by different subsets of normal human mononuclear cells (MNC) in relation to IL-12p40 and TNFα serum levels. Serum samples from 36 pulmonary TB patients and from 22 healthy volunteers were evaluated. To assess angiogenic reaction the leukocytes-induced angiogenesis test according to Sidky and Auerbach was performed. IL-12p40 and TNFα serum levels were evaluated by ELISA. Sera from TB patients significantly stimulated angiogenic activity of MNC compared to sera from healthy donors and PBS (p < 0.001). The number of microvessels formed after injection of lymphocytes preincubated with sera from TB patients was significantly lower compared to the number of microvessels created after injection of MNC preincubated with the same sera (p < 0.016). However, the number of microvessels created after the injection of lymphocytes preincubated with sera from healthy donors or with PBS alone was significantly higher (p < 0.017). The mean levels of IL-12p40 and TNFα were significantly elevated in sera from TB patients compared to healthy donors. We observed a correlation between angiogenic activity of sera from TB patients and IL-12p40 and TNFα serum levels (p < 0.01). Sera from TB patients constitute a source of mediators that participate in angiogenesis and prime monocytes for production of proangiogenic factors. The main proangiogenic effect of TB patients’ sera is mediated by macrophages/monocytes. TNFα and IL-12p40 may indirectly stimulate angiogenesis in TB.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Tuberculosis, Pathogenesis, Interleukin-12p40, Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Introduction

Angiogenesis from preexisting vasculature occurs in many pathological conditions such as tumors [1], cardiovascular diseases [2], chronic inflammation [2, 3], rheumatoid arthritis [4], diabetic retinopathy [5], endometriosis [6], and obesity [7]. In pulmonary nonmalignant diseases angiogenesis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia [8], lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin [9], and sarcoidosis [10]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a fundamental regulator of normal and pathological angiogenesis [11]. Ischemia induces both VEGF production and angiogenesis [12]. Although there have been reports concerning angiogenesis in infectious diseases, its role in the pathogenesis of TB has not been determined [13, 14]. Serum VEGF might be a useful marker as a prognostic indicator in sarcoidosis [15] and other granulomatous diseases, including TB. Increased VEGF levels in serum [16–18], pleural fluid [19, 20] and cerebrospinal fluid [21] have been found in patients with active TB. VEGF therefore may be associated with the pathogenesis of pulmonary TB in the development of the chronic inflammatory reaction [18]. M. tuberculosis antigens are considered an important factor participating in the pathogenesis of Eales’ disease—an idiopathic retinal periphlebitis characterized by capillary nonperfusion and angiogenesis [22]. In one study, an intense angiogenesis was shown ultrastructurally in active pulmonary tuberculosis lesions [23], but the meaning of this phenomenon is not completely understood yet. An important role in the pathogenesis of TB and also in the modulation of angiogenesis is played by some cytokines, especially IL-12 and TNFα [24–26]. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of sera from TB patients on angiogenesis induced by different subsets of normal human mononuclear cells (MNC) in relation to IL-12p40 and TNFα serum levels.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study was approved by the local ethics committee. Serum samples were obtained from 36 patients with active pulmonary TB and from 22 healthy volunteers. The TB group consisted of 26 male and 10 female patients aged 49.8 ± 14.9 years (range = 23-75 years). All were HIV-negative and 23 were smokers. The diagnosis of pulmonary TB was confirmed by a conventional sputum culture. No systemic or extrapulmonary TB was observed. Blood samples were taken from patients before antituberculosis treatment was started. As a control, sera from 22 healthy nonsmoking volunteers were used (12 women and 10 men, mean age = 38.7 ± 11.4, range = 20-58 years). None of the control volunteers had any past medical history of tuberculosis, other pulmonary diseases, or cancer.

Preparation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

Blood from healthy donors attending the Warsaw Central Blood Bank was collected in a heparinized syringe, then diluted 1:1 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and layered over Lymphoprep separation medium (Sigma). After spinning the tubes for 20 min at 500 g, the mononuclear fraction was aspirated from the interface. MNC viability estimated by trypan blue stain was ≥ 98%. This method yielded MNC preparation containing 10-15% monocytes and 85-90% lymphocytes based on morphologic criteria and myeloperoxidase staining. MNC were depleted of monocytes by glass adherence and phagocytosis of iron particles using 15 mg for 10 × 106 cells.

Leukocyte-induced Angiogenesis Assay (LIA)

To assess the effect of sera from TB patients on angiogenesis induced by different fractions of MNC, a leukocyte-induced angiogenesis test described by Sidky and Auerbach in an animal model [27] with modification [10, 28] was used. The local ethical commission for experimenting on animals approved all procedures involved in this study. Female inbred 8-week-old BALB/c mice served as recipients of MNC or lymphocytes preincubated in PBS supplemented with 25% of serum from TB patients or from healthy volunteers for 1 h at 37°C. As a control, other mice were given MNC or lymphocytes that were preincubated only in PBS. Mice were anesthetized with 3.6% chloral hydrate (POCH, Poland) and injected intradermally with 5 × 105 cells in Parker liquid (6 injections per mice and 3 mice for each tested patient). The mice were killed after 3 days. The newly formed blood vessels were identified and counted on the inner surface of the skin of each mouse using a microscope (Nikon, Japan) at 6 × magnification. In all cases identification was performed by one expert (UD) based on the previously described criteria [27].

Cytokines

IL-12p40 and TNFα in sera were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercially available kits (BIOSOURCE Europe S.A.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Recombinant TNFα (NIBSC, Hertfordshire, UK, EN6 3 QG) was used as a standard. Concentrations of IL-12p40 in sera were determined by sandwich ELISA using specific IL-12p40 MoAb. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using spectrophotometric reader Elx800 (Biotek Instruments, Inc., USA).

Statistical Analysis

The value of the angiogenesis test was expressed as an angiogenesis index (AI):

|

where A ex is the mean number of micro blood vessels created after the injection of MNC or lymphocytes preincubated in PBS with the serum of a patient or healthy donor, and A contr is the mean number of micro blood vessels created after the injection of MNC or lymphocytes preincubated with PBS alone

All results are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical evaluation of the results was performed using Pearson’s test, Student’s t-test, and Mann-Whitney test (Statistica 6 for Windows, Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). A p value < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

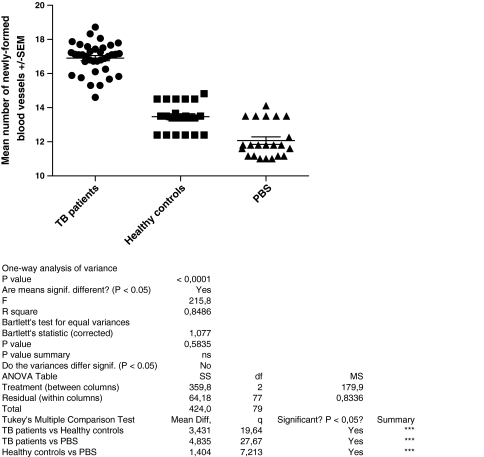

Angiogenic activity of MNC was measured by the mean number of newly formed vessels after injection of MNC preincubated with sera and PBS or with PBS alone. Sera from TB patients significantly indirectly stimulated angiogenesis to a greater extent than sera from healthy donors or PBS alone (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Proangiogenic activity of sera from TB patients (mean number of microvessels = 16.9 ± 0.9) was significantly higher than that of sera from healthy donors (13.99 ± 0.73 vessels; p < 0.001). However, sera from healthy donors also significantly (p < 0.001) stimulated angiogenic activity of normal MNC compared to MNC preincubated only with PBS (12.7 ± 1.16 vessels).

Fig. 1.

Mean number of new vessels after injection of MNC preincubated with sera from TB patients (n = 36), sera from healthy controls (n = 22), and PBS (n = 22). The means are indicated by horizontal bars

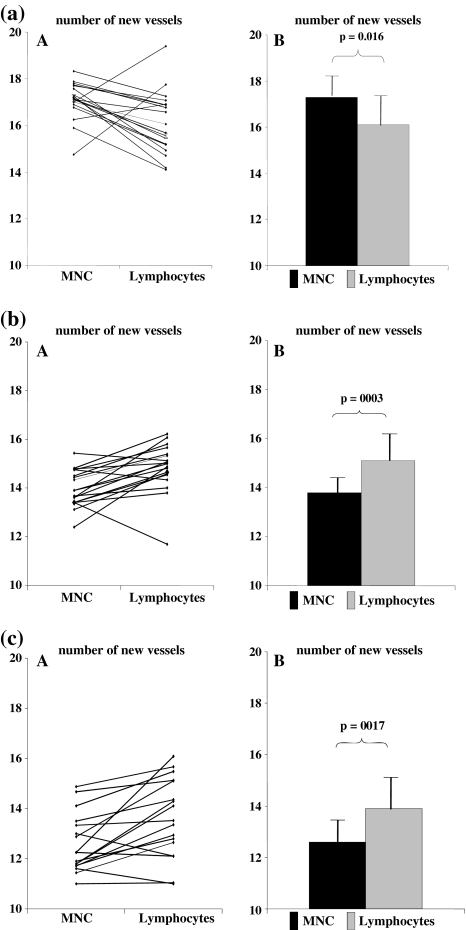

Following the injection of lymphocytes preincubated with sera from 20 TB patients, the mean number of microvessels significantly decreased (16 ± 1.33; p < 0.05) compared to the number of microvessels after the injection of a full suspension of MNC preincubated with the same sera (17 ± 0.79) (Fig. 2a). However, the mean number of microvessels after injection of lymphocytes preincubated with sera from healthy donors significantly increased (from 13.99 ± 0.73 to 14.8 ± 1.0; p < 0.01) compared to the number of microvessels after the injection of a full suspension of MNC preincubated with the same sera (Fig. 2b). A similar effect was observed in the control group when MNC or lymphocytes were preincubated with PBS alone (increase from 12.7 ± 1.16 to 13.8 ± 1.63; p < 0.05) (Fig. 2c). The results were expressed as an angiogenic index and the following relationships were observed: After injection of MNC preincubated with sera from TB patients, AI was 1.29 ± 0.03 but it significantly decreased (1.12 ± 0.09; p < 0.001) following preincubation of lymphocytes with sera from TB patients. However, following the injection of lymphocytes preincubated with sera from healthy volunteers, AI remained the same as after the injection of MNC preincubated with sera from healthy volunteers (1.06 ± 0.04 vs. 1.07 ± 0.06).

Fig. 2.

Mean number of new vessels after injection of MNC and lymphocytes preincubated in the same time (A, individual results; B, mean result). a With sera from TB patients (n = 20). b With sera from healthy donors (n = 22). c Without sera (only in PBS as a control) (n = 22)

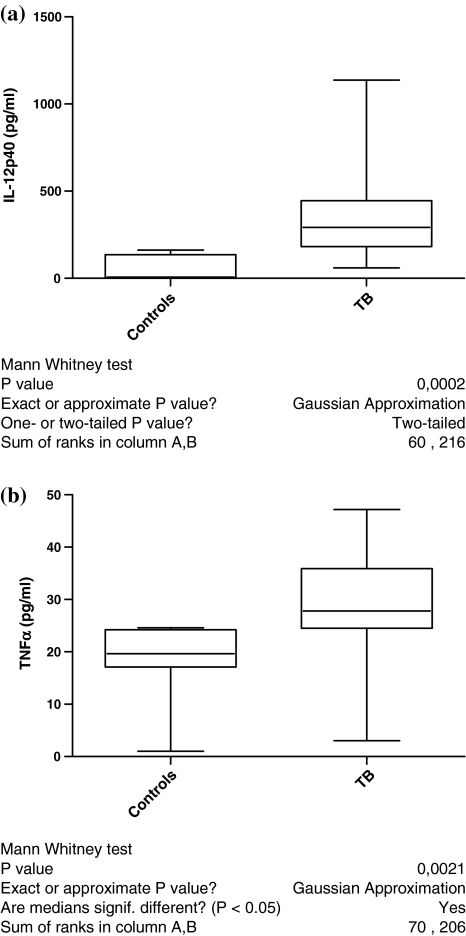

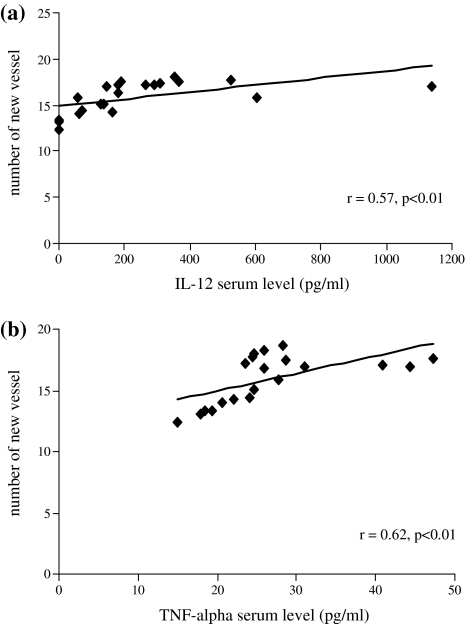

The IL-12p40 serum level was significantly elevated in TB patients (355 ± 279 pg/ml; p < 0.01) compared to that of healthy controls (64 ± 70 pg/ml) (Fig. 3a). A significant correlation was found between the IL-12p40 serum level and angiogenic properties of sera of the examined patients and healthy donors (r = 0.57, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4a). TNFα serum level from TB patients (31 ± 8 pg/ml; p < 0.002) was significantly elevated compared to that of healthy controls (21 ± 3.4 pg/ml) (Fig. 3b). A significant correlation (r = 0.62, p < 0.01) between TNFα serum level and angiogenic activity of sera was found (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

a IL-12p40 serum level from patients with TB (n = 13) and from healthy controls (n = 10). b TNFα serum level from patients with TB (n = 12) and from healthy controls (n = 9)

Fig. 4.

a Correlation between angiogenic activity of sera from TB patients (n = 13) or from healthy controls (n = 10) and IL-12p40 serum level. b Correlation between angiogenic activity of sera from TB patients (n = 12) or from healthy controls (n = 9) and TNFα serum level (r = Pearson’s coefficient)

Discussion

These results confirm suggestions [16, 17] of the involvement of angiogenesis in TB. The positive correlation between angiogenic activity measured by the number of newly created vessels after the injection of MNC preincubated with sera of TB patients and IL-12p40 and TNFα serum concentration levels seems to suggest that these cytokines play an important role in the pathogenesis of the neovascularization [29, 30]. Our previous studies carried out on the same model did not confirm any correlation between angiogenic activity of sarcoidosis patients’ sera and IL-6 and IL-8 serum levels [10]. However, TNFα, an important proinflammatory factor, may stimulate angiogenesis in interstitial lung diseases, and a weak correlation was observed between the serum level of IL-12 and the number of new vessels created after intradermal injection of MNC preincubated with sera from interstitial lung diseases patients [31, 32]. Our results support the hypothesis about the possible link between angiogenic activity of TB patients’ sera and IL-12 and TNFα. These cytokines, which play an important role in the pathogenesis of TB, also modulate angiogenesis [25, 26, 29, 30]. Significant correlations between the concentration of these cytokines and radiological findings in TB patients were found [24]. Some reports point to neovascularization in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Thus, Abe et al. [16] suggest that the increased blood vessel formation and oxygen supply caused by the overexpression of VEGF inhibits cavity formation in TB. However, studies of Alatas et al. [17] did not confirm these findings. These authors observed a significant increase of VEGF serum level in active TB, and a decrease with effective antituberculosis treatment [17]. Matsuyama et al. [18] reported higher VEGF levels in the sera of patients with active pulmonary TB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected monocytes develop a matrix-degrading phenotype [33]. Matrix degradation is the essential first step in the process of creating new vessels from the preexisting vasculature. In TB meningitis, monocytes secrete matrix metalloproteinase-9, which facilitates leukocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier [34]. TNFα plays an important role in this process as well [33]. Lipoarabinomannan, one of the main M tuberculosis antigens, stimulates macrophages to release metalloproteinase-9, which, by breaking down proteins, not only causes formation of cavities but also induces angiogenesis [35]. A correlation between VEGF and TNFα was also observed in the pathogenesis of exudate in tuberculous pleuritis [20]. TNFα is produced by various cells in the inflammatory site and induces angiogenic cytokines, including IL-8, VEGF, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), all of which are involved in neovascularization [36]. Saita et al. [37] demonstrated that intracorneal challenge with trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate derived from M tuberculosis induces an inflammatory response, including granuloma formation and neovascularization. The angiogenic reaction was inhibited by neutralizing antibodies targeting VEGF and IL-8, partially by anti-TNFα antibodies, but not by anti-IL-1β [37]. Macrophages stimulated with cord factor produce proinflammatory type-1 helper-T-cell-inducing cytokines, including TNFα, IL-1, chemotactic factors, and IL-12 [38]. In time it leads to the increase of VEGF concentration [38].

Establishing the key role of the monocytes in inducing angiogenic activity when affected by sera of TB patients is an important result of this study. The angiogenic effect of TB patients’ sera was different than that of sera from healthy donors. Healthy human sera stimulated stronger lymphocytes than monocytes. In the case of TB patients, depletion of monocytes from MNC decreased the proangiogenic effect of the sera; therefore, the proangiogenic factors present in the patients’ sera stimulated mainly monocytes and had no such strong effect on lymphocytes. From this observation we may conclude that the main proangiogenic effect of TB patients’ sera is mediated by macrophages/monocytes. Matsuyama et al. [18] showed by immunohistochemistry that the expression of VEGF occurred in the alveolar macrophages around active TB lesions. It has been demonstrated that VEGF plays a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary M avium complex infection [39]. Therefore, it can be assumed that activated macrophages are the main cells that secrete VEGF in TB lesions when affected by factors such as IL-12 and TNFα. Pulmonary TB and sarcoidosis are granulomatous diseases and their pathogenesis has been linked to monocytes and alveolar macrophages [40, 41]. Meyer et al. [42] pointed out the key role of monocytes from sarcoidosis patients in stimulating neovascularization. In an earlier study we also demonstrated that sera from sarcoidosis patients prime monocytes for production of proangiogenic factors [10]. Sakaguchi et al. [43] indicated that trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate augments VEGF production by neutrophils and macrophages and induces neovascularization in granulomatous tissue. Chronic inflammation in TB is characterized by a localized accumulation of mononuclear cells, i.e., the formation of a granuloma that is surrounded by neovascularization [41]. Angiogenesis is required for the progression of chronic inflammation [3].

IL-12 is a multifunctional cytokine produced by macrophages and dendritic cells. As a factor promoting the commitment of naïve lymphocytes to a Th1-type profile of cytokine expression, IL-12 may be pivotal in the cascade of proinflammatory events in the lungs [44]. The number of cells expressing Th1-type cytokines such as INFγ and IL-12 is increased within the lungs of patients with granulomatous disease such as TB and sarcoidosis [29]. IL-12 not only stimulates the growth of T and NK cells but also inhibits angiogenesis in solid tumors [45]. IL-12 is a heterodimeric cytokine composed of p40 and p34 chains. The subunit of IL-12p40 is in a free form, which blocks specific receptors to stimulate angiogenesis; this determined the selection of this cytokine for this study. Heterodimeric IL-12 and free p40 were present in tuberculous pleural effusions but not in malignant pleural effusions, suggesting that IL-12 is produced in the local immune response to infection [46]. Cooper et al. [47] have demonstrated that IL-12p40 knockout mice are defective in their ability to induce INFγ production and to generate a protective Th1-type of immunologic response in TB. IL-12 proved to be an effective and successful adjuvant to a standard treatment in patients suffering from progressive clinical TB [48].

It is difficult to determine whether neovascularization plays a beneficial or a harmful role in the course of TB. It can only be assumed that the growth of a localized inflammatory mass requires neovascularization. Insufficient angiogenesis resulting in hypoxia creates favorable conditions for tissue necrosis and cavity formation. Therefore, further research on neovascularization and its role in the pathogenesis of TB is necessary.

Conclusions

Sera from TB patients constitute a source of mediators participating in angiogenesis. Sera from TB patients prime monocytes for production of proangiogenic factors. TNFα and IL-12p40 as important proinflammatory factors may stimulate angiogenesis in TB.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffioen AW, Molema G. Angiogenesis: potentials for pharmacologic intervention in the treatment of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic inflammation. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:237–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JR, Seed MP, Kircher CH, Willoughby DA, Winkler JD. The codependence of angiogenesis and chronic inflammation. FASEB J. 1997;11:457–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firestein GS. Starving the synovium: angiogenesis and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:3–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith LE, Shen W, Perruzzi C, Soker S, Kinose F, Xu X, Robinson G, Driver S, Bischoff J, Zhang B, Schaeffer JM, Senger DR. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent retinal neovascularisation by insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Nat Med. 1999;5:1390–1395. doi: 10.1038/70963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers PA, Gargett CE. Endometrial angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 1998;2:287–294. doi: 10.1023/A:1009222030539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crandall DL, Hausman GJ, Kral JG. A review of the microcirculation of adipose tissue: anatomic, metabolic, and angiogenic perspectives. Microcirculation. 1997;4:211–232. doi: 10.3109/10739689709146786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simler NR, Brenchley PE, Horrocks AW, Greaves SM, Hasleton PS, Egan JJ. Angiogenic cytokines in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Thorax. 2004;59:581–585. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.009860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burdick MD, Murray LA, Keane MP, Xue YY, Zisman DA, Belperio JA, Strieter RM. CXCL11 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via inhibition of vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:261–268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1164OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zielonka TM, Demkow U, Białas B, Filewska M, Zycinska K, Radzikowska E, Szopiński J, Skopińska-Rózewska E. Modulatory effect of sera from sarcoidosis patients on mononuclear cells-induced angiogenesis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58(Suppl 5):753–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibuya M. Structure and function of VEGF/VEGF-receptor system involved in angiogenesis. Cell Struct Funct. 2001;26:25–35. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keane MP, Strieter RM. The importance of balanced pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in diffuse lung disease. Respir Res. 2002;3:5–11. doi: 10.1186/rr177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraft A, Weindel K, Ochs A, Marth C, Zmija J, Schumacher P, Unger C, Marmé D, Gastl G. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the sera and effusions of patients with malignant and nonmalignant disease. Cancer. 1999;85:178–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990101)85:1<178::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittermayer F, Pleiner J, Schaller G, Weltermann A, Kapiotis S, Jilma B, Wolzt M. Marked increase in vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations during Escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute inflammation in humans. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:758–761. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sekiya M, Ohwada A, Miura K, Takahashi S, Fukuchi Y. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor as a possible prognostic indicator in sarcoidosis. Lung. 2003;181:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s00408-003-1028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abe Y, Nakamura M, Oshika Y, Hatanaka H, Tokunaga T, Ohkubo Y, Hashizume T, Suzuki K, Fujino T. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and cavity formation in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Respiration. 2001;68:496–500. doi: 10.1159/000050557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alatas F, Alatas O, Metintas M, Ozarslan A, Erginel S, Yildirim H. Vascular endothelial growth factor levels in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest. 2004;125:2156–2159. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.6.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuyama W, Hashiguchi T, Matsumuro K, Iwami F, Hirotsu Y, Kawabata M, Arimura K, Osame M. Increased serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1120–1122. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiropoulos TS, Kostikas K, Gourgoulianis KI. Vascular endothelial growth factor levels in pleural fluid and serum of patients with tuberculous pleural effusions. Chest. 2005;128:468–469. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamed EA, El-Noweihi AM, Mohamed AZ, Mahmoud A. Vasoactive mediators (VEGF and TNF-alpha) in patients with malignant and tuberculous pleural effusions. Respirology. 2004;9:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2003.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuyama W, Hashiguchi T, Umehara F, Matsuura E, Kawabata M, Arimura K, Maruyama I, Osame M. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;186:75–79. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(01)00515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramakrishnan S, Rajesh M, Sulochana KN. Eales’ disease: oxidant stress and weak antioxidant defence. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:95–102. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridley MJ, Heather CJ, Brown I, Willoughby DA. Experimental epithelioid cell granulomas, tubercle formation and immunological competence: an ultrastructural analysis. J Pathol. 1983;141:97–112. doi: 10.1002/path.1711410202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casarini M, Ameglio F, Alemanno L, Zangrilli P, Mattia P, Paone G, Bisetti A, Giosuè S. Cytokine levels correlate with a radiologic score in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:143–148. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brion ChA, Gazzinelli RT. Effect of IL-12 on immune responses to microbial infections: a key mediator in regulating diseases outcome. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:485–496. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80093-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergron A, Bonay M, Kambouchner M, Lecossier D, Riquet M, Soler P, Hance A, Tazi A. Cytokine patterns in tuberculous and sarcoid granulomas. J Immunol. 1997;159:3034–3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidky YA, Auerbach R. Lymphocyte-induced angiogenesis: a quantitative and sensitive assay for the graft-versus-host reaction. J Exp Med. 1975;141:1084–1100. doi: 10.1084/jem.141.5.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zielonka TM, Demkow U, Filewska M, Bialas B, Zycinska K, Radzikowska E, Wardyn AK, Skopinska-Rozewska E. Angiogenic activity of sera from extrinsic allergic alveolitis patients in relation to clinical, radiological, and functional pulmonary changes. Lung. 2010;188:375–380. doi: 10.1007/s00408-010-9228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taha RA, Minshall EM, Olivenstein R, Ihaku D, Wallaert B, Tsicopoulos A, Tonnel AB, Damia R, Menzies D, Hamid QA. Increased expression of Il-12 receptor mRNA in active pulmonary tuberculosis and sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1119–1123. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9807120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvaraj P, Sriram U, Mathan Kurian S, Reetha AM, Narayanan PR. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (−238 and −308) and beta gene polymorphisms in pulmonary tuberculosis: haplotype analysis with HLA-A, B and DR genes. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:335–341. doi: 10.1054/tube.2001.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zielonka TM, Demkow U, Filewska M, Bialas B, Korczynski P, Szopinski J, Soszka A, Skopinska-Rozewska E. Angiogenic activity of sera from interstitial lung diseases patients to IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 and TNFα serum level. Centr Eur J Immunol. 2007;32:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zielonka TM, Demkow U, Puscinska E, Golian-Geremek A, Filewska M, Zycinska K, Bialas-Chromiec B, Wardyn KA, Skopinska-Rozewska E. TNFalpha and INFgamma inducing capacity of sera from patients with interstitial lung disease in relation to its angiogenesis activity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58(Suppl 5):767–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duan L, Gan H, Arm J, Remold HG. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 participates with TNFα in the induction of human macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. J Immunol. 2001;166:7469–7476. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price NM, Farrar J, Tran TT, Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Friedland JS. Identification of a matrix-degrading phenotype in human tuberculosis in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;166:4223–4230. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JC, Wysocki A, Tchou-Wang KM, Moskowitz N, Zhang Y, Rom WN. Effect of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its components on macrophages and the release of matrix metalloproteinases. Thorax. 1996;51:306–311. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida S, Ono M, Shono T, Izumi H, Ishibashi T, Suzuki H, Kuwano M. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4015–4023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saita N, Fujiwara N, Yano I, Soejima K, Kobayashi K. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces corneal angiogenesis in rats. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5991–5997. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.10.5991-5997.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oswald IP, Dozois CM, Petit JF, Lemaire G. Interleukin-12 synthesis is a required step in trehalose dimycolate-induced activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1364–1369. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1364-1369.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishigaki Y, Fujiuchi S, Fujita Y, Yamazaki Y, Sato M, Yamamoto Y, Takeda A, Fujikane T, Shimizu T, Kikuchi K. Increased serum level of vascular endothelial growth factor in Mycobacterium avium complex infection. Respirology. 2006;11:407–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis: immunopathogenic concepts and their clinical application. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:716–738. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12030716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi K, Yoshida T. The immunopathogenesis of granulomatous inflammation induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods. 1996;9:204–214. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer KC, Kaminski MJ, Calhoun WJ, Auerbach R. Studies of bronchoalveolar lavage cells and fluids in pulmonary sarcoidosis. I. Enhanced capacity of bronchoalveolar lavage cells from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis to induce angiogenesis in vivo. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1446–1449. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaguchi I, Ikeda N, Nakayama M, Kato Y, Yano I, Kaneda K. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate (cord factor) enhances neovascularization through vascular endothelial growth factor production by neutrophils and macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2043–2052. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.4.2043-2052.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manetti R, Parronchi P, Giudizi MG, Piccinni MP, Maggi E, Trinchieri G, Romagnani S. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (IL-12) induces T helper type (Th1) specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4 producing Th cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1199–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duda DG, Sunamura M, Lozonschi L, Kodama T, Egawa S, Matsumoto G, Shimamura H, Shibuya K, Takeda K, Matsuno S. Direct in vitro evidence and in vivo analysis of the antiangiogenesis effects of interleukin 12. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1111–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang M, Gately MK, Wang E, Gong J, Wolf SF, Lu S, Modlin RL, Barnes PF. Interleukin 12 at the site of disease in tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1733–1739. doi: 10.1172/JCI117157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper AM, Magram J, Ferrante J, Orme IM. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:39–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greinert U, Ernst M, Schlaak M, Entzian P. Interleukin-12 as successful adjuvant in tuberculosis treatment. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1049–1051. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17510490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]