Abstract

Background

Finnmark County is the northernmost county in Norway. For several decades, the rate of mortality after injury in this sparsely inhabited region has remained above the national average. Following documentation of this discrepancy for the period 1991–1995, improvements to the trauma system were implemented. The present study aims to assess whether trauma-related mortality rates have subsequently improved.

Methods

All injury-associated fatalities in Finnmark from 1995–2004 were identified retrospectively from the National Registry of Death and reviewed. Low-energy trauma in elderly individuals and poisonings were excluded.

Results

A total of 453 cases of trauma-related death occurred during the study period, and 327 of those met the inclusion criteria. Information was retrievable for 266 cases. The majority of deaths (86%) occurred in the prehospital phase. The main causes of death were suicide (33%) and road traffic accidents (21%). Drowning and snowmobile injuries accounted for an unexpectedly high proportion (12 and 8%, respectively). The time of death did not show trimodal distribution. Compared to the previous study period, there was a significant overall decline in injury-related mortality, yet there was no change in place of death, mechanism of injury, or time from injury until death.

Conclusions

Changes in injury-related mortality cannot be linked to improvements in the trauma system. There was no change in the epidemiological patterns of injury. The high rate of on-scene mortality indicates that any major improvement in the number of injury-related deaths lies in targeted prevention.

Introduction

Trauma is a major cause of death worldwide [1]. Analysis of the time and place of deaths due to injury is a useful tool in the planning of a trauma system, as well as in identifying areas that might benefit from additional research.

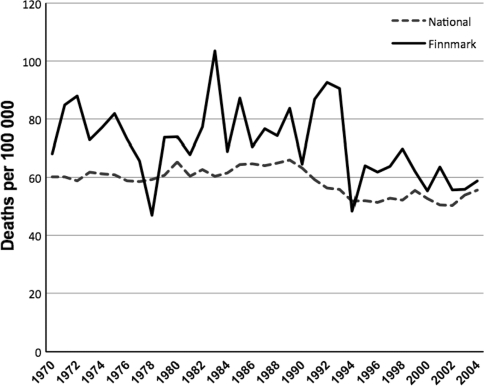

Finnmark County is the northernmost county in Norway. This rural county (48,000 km2) is comparable in size to Belgium but with a population of 72,500 [2]. Rural areas have a higher rate of injury-related deaths than urban areas [3–6], which has been attributed to longer travel distances, delayed surgical care, fewer personnel trained in advanced life support techniques, and behavioral patterns among the populace [7–11]. Finnmark has had an injury-related death rate well above the national average for decades (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Annual mortality rate from injury and poisonings in the Norwegian county of Finnmark compared to the national Norwegian average (ICD-10 V01-Y89)

We previously reported the mechanism of injury, place of death, and duration of time from injury to death in Finnmark for the time period 1991–1995 [12]. Since then, trauma care has improved in the region. Ambulance services are now tied to the hospitals rather than to local owners, and their equipment has been expanded and standardized. For prehospital personnel, educational requirements have been heightened and standard operating procedures developed. A training program in trauma care (The BEST Foundation: better and systematic trauma care), comprising both in-hospital and out-of-hospital services has been implemented [13]. Additionally, a national suicide prevention program was launched in the autumn of 1994, which aimed to increase knowledge about suicide and suicide prevention among both health care personnel and the public through information and training. The regional center encompassing Finnmark County was established in 1996 [14, 15]. Psychiatric health care in the region was further strengthened through the national development of community psychiatry services in all counties beginning in 1999 [16].

Despite these steps, injury-related mortality seems to remain above the national average in Finnmark County. A recent study from Stavanger, a city on the western coast of Norway, described the contemporary patterns of trauma epidemiology in an urban area [17]. This study showed an increase in in-hospital deaths and in older victims compared to previous data. The aims of the present study was therefore to describe fatal injuries in a well-defined rural region and to assess possible changes after developments in trauma care.

Materials and methods

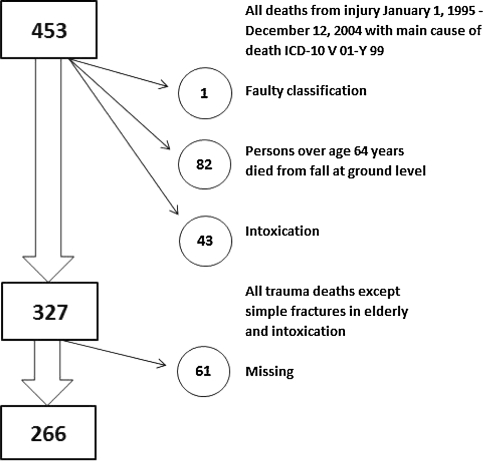

The Norwegian National Registry of Death routinely records all deaths in Norway based on death certificates. We obtained information for all deaths from injury and poisoning (ICD-10 V01-Y89) occurring in Finnmark County in the period January 1, 1995, through December 31, 2004. We also included those cases of injuries occurring in Finnmark in which death occurred after transfer to an out-of-county hospital. We excluded from the study deaths from isolated, simple fractures after a fall at ground level occurring in persons over age 64 years, and all poisonings (Fig. 2). The criteria used were the same as those of the previous study [12]. For each case, we reviewed ambulance and hospital records and police and autopsy reports (where available). Information on cause of injury, time and place of death, and demographic data were recorded in a standard form. To investigate changes over time, we divided our material into two periods, 1996–1999 and 2000–2004, and used the material from our previous study to compare the period 1991–1995.

Fig. 2.

Process of inclusion and exclusion of data

The county studied covers 48,000 km and has 72,500 inhabitants. The population mostly consists of Norwegians, Sami (an indigenous people of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula), and Kvens (an ethnic minority descending from Finish immigrants). As ethnicity is not recorded during censuses, the exact composition of the population is not known. In 1972 an estimated 15,000 Sami lived in Finnmark, representing 20% of the population. The Sami have a history of oppression and assimilation from Norwegian authorities, but as of today are entitled to special protection and rights [18, 19].

Life expectancy in Sami areas is somewhat shorter than that of the country in general. The Sami alcohol consumption does not exceed that of the non-Sami populace, and Sami use psychiatric health care at a comparable rate to Norwegians. Finnmark County has a lower level of education than the country in general; 55% have a high school education as the highest degree and 21% have education from college or university [18–21]. In 1995, Finnmark had the second highest alcohol consumption among Norwegian counties, surpassed only by the county of Oslo; each inhabitant consumed an average of 6.44 l of alcohol per year [22].

SPSS version 17.0 was used for statistical analysis. Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical data. The Norwegian Directorate for Health and Social Affairs (07/4817), the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (07/01595-3/clu), the Privacy Ombudsman for Research (17430/2/LT), the Norwegian Director of Public Prosecutions (Ra 07-526 IFO/mw 639.2), and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (200702984-3/IAY/400) approved this study.

Results

During the 10-year period, 453 deaths from injury and poisoning were recorded in Finnmark County, yielding an annual mortality rate of 61 per 100,000 inhabitants. This rate is significantly higher (p < 0.001) than that of the country as a whole, at 54 injury- and poisoning deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. A total of 327 cases met the inclusion criteria, and hospital, autopsy, or police records we identified for 266 of these. Not all cases had complete information.

Median age was 41.5 years, and 49% of those who died were under the age of 40. Eighty-three percent were male. Autopsy was performed in 144 of the cases (44%). Forty-two percent of deaths occurred on Saturdays and Sundays (chi-square for difference, p < 0.001), with the remaining deaths distributed evenly throughout the week (chi-square for difference, p = 0.920). There was no variation according to season (p = 0.892) or month (p = 0.377). None of the major cause-of-death subgroups displayed seasonal variation, with the exception of suicide, which varied according to month (p = 0.007). Most suicides occurred in the months of May (17%), December (16%), and September (13%).

The leading cause of death was suicide, which accounted for 33%. Among these, two-thirds were hangings and one-third were shootings. Road traffic accidents were the second most common cause of death, accounting for 21%. Drowning accounted for 12%, and injuries caused by snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles (ATV) for 8%. The remaining deaths were due to fires (7%), falls (6%), homicide (5%), and machinery (3%). Five percent of the cases did not fall into any of these categories.

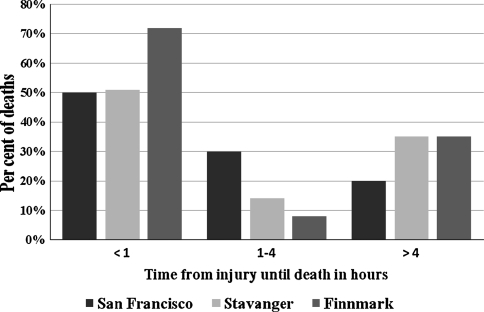

Table 1 gives the places of death. Death occurred in the prehospital phase for 86% (228/266), and 72% (191/266) died prior to the arrival of medical personnel. We determined the time from injury to death in 181 of the 266 cases (Table 2). For the remaining 85 cases (32%), information was not sufficient to determine time from injury until death, but most (n = 82) of these occurred in the prehospital phase and are likely to have died within an hour of injury. Figure 3 illustrates mortality after injury in relation to time.

Table 1.

Place of death for 266 patients according to mechanism of injury

| Mechanism of injury | Number | Place of death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At site of injury priora | At site of injury aftera | In transfer | Emergency room | During admission | Later | Missing | ||

| Suicide | 87 (33%) | 80 (92%) | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| RTA | 56 (21%) | 29 (52%) | 9 (16%) | 4 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 12 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Drowning | 32 (12%) | 30 (94%) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| ATV/snowmobile | 20 (8%) | 16 (80%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Fire | 19 (7%) | 12 (63%) | 3 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fall | 16 (6%) | 6 (38%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (31%) | 3 (19%) | 0 (0%) |

| Homicide | 14 (5%) | 6 (43%) | 3 (21%) | 2 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Machinery | 7 (3%) | 3 (43%) | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hypothermia | 6 (2%) | 4 (67%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 9 (3%) | 5 (56%) | 1 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) |

| Total | 266 (100%) | 191 (72%) | 29 (11%) | 9 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 28 (11%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) |

ATV all terrain vehicle, RTA road traffic accident

aSite of Injury has been divided into deaths prior to and after the arrival of health personnel

Table 2.

Distribution of time from injury until death for 266 patients according to mechanism of injury

| Mechanism of injury | Number | Time from injury until death | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 h | 1–4 h | >4 h | Unknown | ||

| Suicide | 87 (33%) | 59 (68%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 27 (31%) |

| RTA | 56 (21%) | 31 (55%) | 5 (9%) | 11 (20%) | 9 (16%) |

| Drowning | 32 (12%) | 10 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (66%) |

| ATV/snowmobile | 20 (8%) | 9 (45%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (15%) | 8 (40%) |

| Fire | 19 (7%) | 13 (68%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (16%) | 2 (11%) |

| Fall | 16 (6%) | 2 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (50%) | 5 (31%) |

| Homicide | 14 (5%) | 6 (43%) | 1 (7%) | 3 (21%) | 4 (29%) |

| Machinery | 7 (3%) | 5 (71%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14%) | 1 (14%) |

| Hypothermia | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (83%) |

| Other | 9 (3%) | 4 (44%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (33%) |

| Total | 266 (100%) | 139 (52%) | 11 (4%) | 31 (12%) | 85 (32%) |

Fig. 3.

Comparison of time from injury until death in three data sets after adjusting our data to fit the inclusion criteria for the Stavanger [20] and San Francisco [2] studies (i.e., excluding deaths from hanging, drowning, burns, and hypothermia)

In Fig. 3, we compare our time distribution to Trunkey’s original findings, the trimodal distribution taught by textbooks [23], as well as to results from a recent Norwegian study [17], after our data were made compatible by exclusion of deaths from hanging, drowning, and burns. Finnmark is shown to have a higher share of deaths occurring within an hour from injury than its urban counterparts. No other stratification of data yielded a trimodal distribution. When excluding all those who died prior to arrival of healthcare personnel, 32% died within 1 h, 12% within the next hour, and thereafter 1–3% continuously each hour until the seventh hour from injury, whereafter deaths occurred more sporadically.

In 40% of the cases the deceased was under the influence of an intoxicating substance, most commonly alcohol (71%). For the subgroups homicide and ATV/snowmobile this share was higher at 79% and 65%, respectively. The rate of intoxicating substance was lower for machinery (0%) and road traffic accidents (30%).

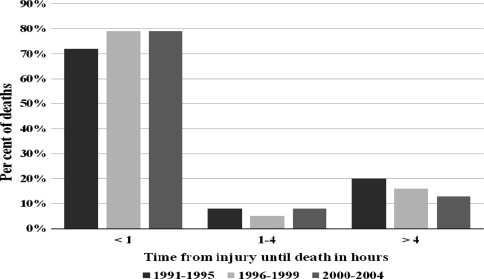

We found no significant difference between the three defined time periods with respect to mechanism of injury, place of death, and time from injury until death (p = 0.326, p = 0.95, and p = 0.661, respectively; Fig. 4), nor did we find any difference in age (p = 0.789). There were no differences between time periods after exclusion of drowning, suicide, and fire, all of which represent causes of death that are usually beyond the aid of any trauma system. When looking for changes over time in the major subgroups, deaths from drowning showed a declining rate, but this change was not significant (p = 0.054). Still, as Fig. 1 shows, there has been a significant (p = 0.02) decline in the mortality rate from external causes from the beginning of the 1990s, and Finnmark is now approaching the national mean.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the distribution of time from injury until death among three time periods

Discussion

This study shows that the northernmost and most deprived county in Norway still has a high rate of injury-related death. We found no apparent change in the epidemiological pattern of injury, contrary to a recent study from urban Norway [17]. Thus we were unable to detect any effects of strengthened ambulance services, training of trauma teams, increased awareness against suicide, or other attempts to reduce injury-related mortality.

The majority of deaths (86%) still occur in the prehospital phase. Likewise the distribution of time from injury to death, in which first-hour deaths comprise 77%, remains unchanged. The proportion of prehospital and first-hour category death is high compared to urban studies [17, 24, 25], and in that context the proportion of suicide in the present study seems striking. The suicide rate appears high in comparison to the Stavanger study [17], which in turn could explain the high share of early deaths. This is however only true if one does not take into account that hangings and drowning were omitted from that study; if the same omission is made in our material, the suicide rates are congruous, and the first-hour death category remains comparatively high in Finnmark, as can be seen from Fig. 3. However, this is in line with contemporary rural and mixed urban/rural studies [10, 26–28]. The Stavanger study reported an increasing proportion of in-hospital deaths, as well as a simultaneous increase in age of trauma patients. Fatal injury in older patients is associated with decreased injury severity [17, 29], and as we do not see the same increase in age in the trauma population of Finnmark, this might explain that difference. The Stavanger study does not report a decrease in Injury Severity Score as would be expected.

For the years 2002–2004 the mean length of an ambulance assignment in the region was 96 km [2]. The high rate of prehospital deaths and deaths within one hour are likely the result from long travel distances and hence prolonged response and transport times. Late discovery may play a role in typically unwitnessed accidents such as drownings and snowmobile injuries. The high rate of prehospital death in Finnmark may explain why we do not see a shift toward an increase in-hospital deaths, as there are fewer patients likely to benefit from changes to the trauma care system. The lack of increase in age could be attributed to more work-related deaths (drowning and machinery), a lower share of falls (associated with increased age [6, 30, 31]), and a higher share of road traffic injuries (associated with young age [6, 32]) in Finnmark.

Our analysis did not yield the trimodal distribution reported by Trunkey and taught in textbooks, even when excluding suicide, drownings, and fire, which represent incidents that in most cases will be beyond any help the trauma system can provide. The applicability of this model both for rural settings and urban areas with a modern trauma system has been questioned in several other studies [12, 17, 25–28, 33–35].

In an assessment of changes over time, the mortality rate for Finnmark dropped significantly during the early 1990s (Fig. 1), a finding that coincides with developments in trauma care. Yet, if these developments were the cause of the reduced mortality rate, one would expect some changes in the pattern of time and place of death, such as a relative rise in the share of prehospital deaths, as the in-hospital deaths are more likely to be reduced by developments of trauma care. Also, one would expect changes in the patterns of injury, with a larger share of deaths being caused by suicide and drowning, as these groups are often not aided by trauma care. Because such changes are not seen, it is unlikely that the reduction in trauma-related death rate is attributable to trauma care developments alone. The aforementioned steps in suicide prevention were not implemented in the county until the late 1990s, and the drop in mortality occurs too early for these developments to be the root cause. In fact, it is reasonable to expect several years to pass before an effect is seen; thus it is not surprising that we found no difference in suicide rate between the time periods. The decline in deaths from drowning, though not quite significant, does coincide with a notable and continuous reduction in persons employed in fishing during the last 30 years [36].

It is probable that the decline is the result of several cumulative factors, such as those mentioned above, and that the population at risk is too small for statistical detection of the effects independently. In Fig. 1 we might find a different explanation for the lack of change in the epidemiological pattern compared to urban Norway. As can be seen from Fig. 1, there was a drop in nationwide mortality rates approximately 10 years prior to the decline in the rate for Finnmark. It is plausible that there is a corresponding delay in epidemiological distribution and that the change in age and place of death will be seen in Finnmark in future years.

This study has several limitations. In this part of Norway, autopsies are not routinely performed due to lack of funding for the police. This is in contrast to the study from urban Western Norway [17] in which more than 95% of victims underwent autopsy. The low autopsy rate in our study rendered Injury Severity Scoring and assessment of injury survivability impossible. For 61 cases, we found no records either in the hospital or police archives. This lack is attributable to the retrospective nature of the study, with cases dating back as far as 13 years at the time of data collection, with the restructuring of organizations and archive procedures. Some deaths may have occurred in nursing homes, with no subsequent hospitalization or police investigation.

As shown, the identified time and cause of death in Finnmark seem to be mostly in line with what can be expected for a rural area, with a high prehospital death rate, no trimodal distribution, and a high rate of motor vehicle accidents and suicide. We do not see the change in epidemiological pattern described for urban Norway. Whether this is attributable to fundamental differences between urban and rural trauma, or if similar changes in distribution can be expected to occur in rural areas in the future remains to be determined. Another question that remains is why Finnmark has a higher injury-related death rate than the rest of Norway. This may be explained by the high rate of drowning and ATV-related deaths. To determine this unequivocally, however, a thorough comparison to other Norwegian counties would be necessary. Although the death rate now approaches the national average, we nevertheless should continue searching for methods to further reduce the injury-related death rate. The high rate of on-scene mortality indicates that any major impact on the number of injury-related deaths will come from directing efforts at prevention.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.WHO Fact sheet No. 310 (2008) Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html. Accessed April 2011

- 2.Statistisk sentralbyrå (Statistics Norway) Available at: http://statbank.ssb.no//statistikkbanken/default_fr.asp?PLanguage=1. Accessed April 2011

- 3.Coben JH, Tiesman HM, Bossarte RM, et al. Rural-urban differences in injury hospitalizations in the U.S., 2004. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esposito TJ, Sanddal ND, Hansen JD, et al. Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and inappropriate trauma care in a rural state. J Trauma. 1995;39:955–962. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199511000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann C. Mortality among seriously injured patients treated in remote rural trauma centers before and after implementation of a statewide trauma system. Med Care. 2001;39:643–653. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200107000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatovich DM, Jacobs IG. The relationship between remoteness and trauma deaths in Western Australia. J Trauma. 2009;67:910–914. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181815a26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossman DC, Kim A, Macdonald SC, et al. Urban-rural differences in prehospital care of major trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:723–729. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199704000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr BG, Caplan JM, Pryor JP, et al. A meta-analysis of prehospital care times for trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10:198–206. doi: 10.1080/10903120500541324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwerling C, Merchant JA, Nordstrom DL, et al. Risk factors for injury in rural Iowa: round one of the Keokuk County Rural Health Study. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:230–233. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Hoyt DB, et al. Trauma deaths in a mature urban vs rural trauma system. A comparison. Arch Surg. 1997;132:376–381. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW, Brenneman FD. Noncompliance with seat-belt use in patients involved in motor vehicle collisions. Can J Surg. 2005;48:367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisborg T, Hoylo T, Siem G. Death after injury in rural Norway: high rate of mortality and prehospital death. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:153–156. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisborg T, Brattebo G, Brinchmann-Hansen A, et al. Effects of nationwide training of multiprofessional trauma teams in Norwegian hospitals. J Trauma. 2008;64:1613–1618. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31812eed68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sørås I. The Norwegian plan for suicide prevention 1994–1999 evaluation findings. Nor J Suicidol. 2000;5:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehlum L, Reinholdt NP. The Norwegian plan for suicide prevention follow-up project 2000–2002: building on positive experiences. Nor J Suicidol. 2001;6:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norwegian Board of Health Supervision (2001) Distriktspsykiatriske sentre - organisering og arbeidsområder 1:3

- 17.Soreide K, Kruger AJ, Vardal AL, et al. Epidemiology and contemporary patterns of trauma deaths: changing place, similar pace, older face. World J Surg. 2007;31:2092–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistisk sentralbyrå (Statistics Norway). Sami in Norway. Available at: http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/00/00/10/samer_en/2011. Accessed January 2011

- 19.Nordic Sami Institute. Sami Social Science Database. Available at: http://www.sami-statistics.info/default.asp. Accessed January 2011

- 20.Sorlie T, Nergard JI. Treatment satisfaction and recovery in Saami and Norwegian patients following psychiatric hospital treatment: a comparative study. Transcult Psychiatry. 2005;42:295–316. doi: 10.1177/1363461505052669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edin-Liljegren A, Hassler S, Sjolander P, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among Swedish Sami—a controlled cohort study. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(Suppl 2):292–297. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services (1995) NOU 1995: 6 Plan for health and social services for the Sami population of Norway

- 23.Trunkey DD. Trauma. Accidental and intentional injuries account for more years of life lost in the U.S. than cancer and heart disease. Among the prescribed remedies are improved preventive efforts, speedier surgery and further research. Sci Am. 1983;249:28–35. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0883-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung Kon Jin PH, Klaver JF, Maes A, et al. Autopsies following death due to traumatic injuries in the Netherlands: an evaluation of current practice. Injury. 2008;39:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demetriades D, Kimbrell B, Salim A, et al. Trauma deaths in a mature urban trauma system: is “trimodal” distribution a valid concept? J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans JA, van Wessem KJ, McDougall D, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic deaths: comprehensive population-based assessment. World J Surg. 2009;34:158–163. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang JM, Civil I, Ng A, et al. Is the trimodal pattern of death after trauma a dated concept in the 21st century? Trauma deaths in Auckland 2004. Injury. 2008;39:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyatt J, Beard D, Gray A, et al. The time of death after trauma. BMJ. 1995;310:1502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6993.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clement ND, Tennant C, Muwanga C. Polytrauma in the elderly: predictors of the cause and time of death. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010;18:26. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomberg BF, Gruen GS, Smith WR, et al. Outcomes in acute orthopaedic trauma: a review of 130,506 patients by age. Injury. 1999;30:431–437. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(99)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy RL, Grant PT, Blackwell D. Low-impact falls: demands on a system of trauma management, prediction of outcome, and influence of comorbidities. J Trauma. 2001;51:717–724. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elliott S, Woolacott H, Braithwaite R. The prevalence of drugs and alcohol found in road traffic fatalities: a comparative study of victims. Sci Justice. 2009;49:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGwin G, Jr, Nunn AM, Mann JC, et al. Reassessment of the tri-modal mortality distribution in the presence of a regional trauma system. J Trauma. 2009;66:526–530. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181623321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meislin H, Criss EA, Judkins D, et al. Fatal trauma: the modal distribution of time to death is a function of patient demographics and regional resources. J Trauma. 1997;43:433–440. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Knegt C, Meylaerts SA, Leenen LP. Applicability of the trimodal distribution of trauma deaths in a Level I trauma centre in the Netherlands with a population of mainly blunt trauma. Injury. 2008;39:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finnmark County Authority (2010) Finnmark Facts. Available at: http://www.ffk.no/fakta/statistikk/default.aspx?mid=43. Accessed January 2011