Abstract

The proteasome plays a pivotal role in the cellular response to oxidative stress. Here, we used biochemical and mass spectrometric methods to investigate structural changes in the 26S proteasomes from yeast and mammalian cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Oxidative stress induced the dissociation of the 20S core particle from the 19S regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome, which resulted in loss of the activities of the 26S proteasome and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. H2O2 triggered the increased association of the proteasome-interacting protein Ecm29 with the purified 19S particle. Deletion of ECM29 in yeast cells prevented the disassembly of the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress, and ecm29 mutants were more sensitive to H2O2 than were wild-type cells, suggesting that separation of the 19S and 20S particles is important for cellular recovery from oxidative stress. The increased amount of free 20S core particles was required to degrade oxidized proteins. The Ecm29-dependent dissociation of the proteasome was independent of Yap1, a transcription factor that is critical for the oxidative stress response in yeast, and thus functions as a parallel defense pathway against H2O2-induced stress.

Introduction

Proteasomes are multicatalytic protease complexes that play an important role in the degradation of proteins, including normal, damaged, mutated and misfolded proteins (1). The 26S proteasome is responsible for adenosine triphosphate (ATP)– and ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation in the nucleus and the cytosol (2, 3). It consists of two subcomplexes, the 20S catalytic core particle and the 19S regulatory particle. The 20S core is made up of arrangements of seven α and seven β subunits, which assemble into a conserved cylindrical structure as four heptameric stacked rings in the order αββα. The 20S core harbors various catalytic activities, including chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and peptidylglutamyl-peptide hydrolase activities (2, 4). The 19S particle is composed of at least 19 different subunits, which can be further divided by biochemical means into two subcomplexes: the base and the lid (5). The base is located proximal to the 20S core and contains six adenosine triphosphatases (ATPases) (Rpt1 to Rpt6) and four non-ATPase subunits (Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, and Rpn13). The lid is distal to the base and contains nine non-ATPase subunits (Rpn3, Rpn5 to Rpn9, Rpn11, Rpn12, and Rpn15) (6). In contrast to that of the 20S core, the structure and function of the 19S particle is less well characterized. Nevertheless, it is thought to perform a number of biochemical functions, including recognition of polyubiquitinated substrates (7, 8), cleavage of polyubiquitin chains to recycle ubiquitin (9), unfolding of substrates, assisting in opening the gate of the 20S chamber, and subsequently translocating unfolded substrates into the catalytic chamber (3). The activities of the 19S particle and its assembly with the 20S core are strictly ATP-dependent. Compared to the 20S core, which degrades small peptides and fully unfolded proteins in an ATP-independent manner, the 26S proteasome generally requires not only ATP, but also a polyubiquitin chain conjugated to the substrate protein to degrade proteins.

Regulation of the activity of the proteasome is complex because a multitude of factors influence the protein degradation process. The activity of the 20S core is regulated by a number of activator proteins in addition to the 19S particle. Three additional mammalian 20S activators have been identified: PA28αβ, PA28γ, and PA200 (10–13). These activators are thought to modulate the structure of the 20S core by controlling the opening of the channel of α rings, and therefore facilitating the entry of unfolded substrates for degradation. In addition to regulation by proteasome activator proteins, the function of the proteasome complex is further regulated by posttranslational modifications and by interacting partners (6, 14–16).

Oxidative stress is implicated in aging and a number of pathologies (17–19). The reactive oxygen species that are generated by aerobic metabolism and environmental stressors can target and chemically modify proteins and affect their biological functions. Cells have protein repair pathways to rescue oxidized proteins and restore their functions; however, oxidized proteins can undergo direct chemical fragmentation or form large aggregates and thus become cytotoxic (18). Therefore, removal of oxidatively damaged proteins is of critical importance to maintain normal cell homeostasis and viability. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the proteasome plays a pivotal role in the selective recognition and degradation of oxidized proteins (17, 18, 20). Inhibition or removal of proteasomes results in loss of the ability of cells to degrade oxidized proteins. H2O2, a common oxidant, induces cellular oxidative stress and affects the proteolytic activities of proteasomes. The 20S and 26S proteasomes appear to have different sensitivities to H2O2-induced stress (21, 22). The 20S proteasome is relatively resistant to oxidative stress, it can maintain its activity even upon treatment with moderate to high concentrations of H2O2, whereas the 26S proteasome is much more vulnerable (21–24).

In addition, the activity of the ubiquitin-activating and -conjugating system is subject to change during oxidative attack. Clearly, an oxidation-dependent regulation of the proteasome system exists in cells, which is involved in controlling the balance between the repair and the degradation of damaged proteins and is thus central to the stress response. Although the 20S core is believed to be mostly responsible for degrading oxidized proteins (17, 19), it is still unclear whether the 20S core can function on its own to degrade oxidized proteins in vivo as has been shown in vitro. In addition, how the proteolysis of oxidized proteins is regulated and how oxidative stress modulates the structure and function of the proteasome remains largely undefined. Further understanding of how the proteasome-dependent degradation pathway is regulated in response to oxidative stress may provide a molecular basis for developing new strategies to prevent the formation of intracellular protein aggregates during aging and in neurodegenerative disorders. To this end we used biochemical and mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomic approaches to determine the molecular changes in 26S proteasome complexes and how these changes are regulated. Here, we identified the proteasome modulator protein Ecm29 as a key component in regulating the structure of the proteasome in response to H2O2-induced stress. Our findings uncover a previously unrecognized mechanism that regulates the function of the 26S proteasome during oxidative stress and suggest a model for the control of 26S proteasome activity under various environmental conditions.

Results

The yeast 26S proteasome becomes disassociated in response to H2O2-induced stress

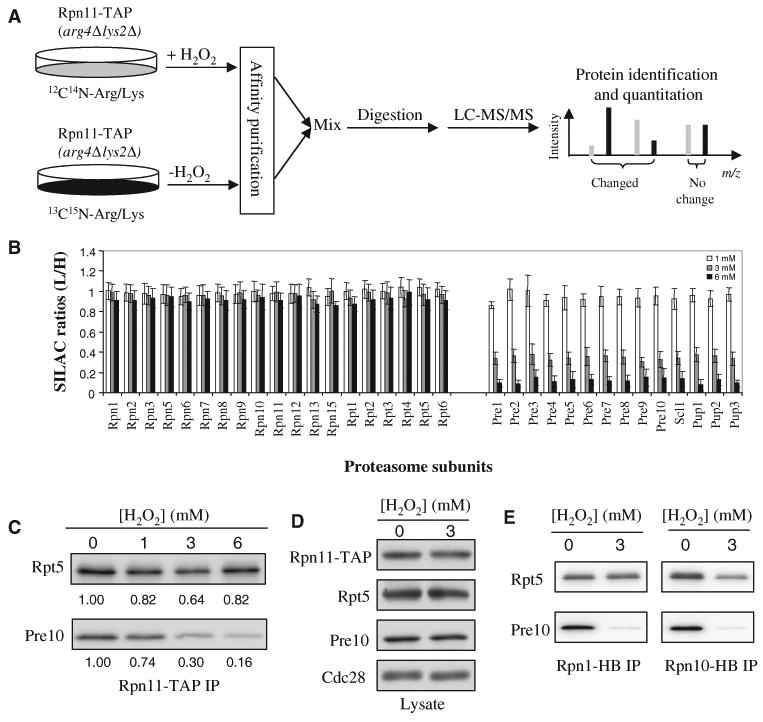

To elucidate the regulation of the 26S proteasome in response to H2O2-induced stress, we used affinity purification and stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)–based quantitative MS to examine structural changes in the yeast 26S proteasome complex (Fig. 1A) (25, 26). The 26S proteasome complex was purified from yeast cells that contained the tandem affinity purification (TAP)–tagged 19S proteasomal subunit Rpn11 by binding to immunoglobulin G (IgG) beads followed by elution with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease. To unambiguously identify proteins that specifically interacted with 26S proteasome complexes, we used the MAP (mixing after purification)–SILAC method for the quantitative comparison of proteasome complexes isolated from cells exposed to various concentrations of H2O2 (26). With this method, we purified the proteasome complexes from treated and untreated cells separately and then mixed them for subsequent protease digestion and liquid chromatography–tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analysis to determine quantitative changes in subunit composition.

Fig. 1.

Disassembly of the yeast 26S proteasome in response to H2O2-induced stress. (A) The MAP-SILAC MS strategy for identifying and quantitating H2O2 stress–induced structural changes in the yeast 26S proteasome. (B) Average SILAC ratios (L/H) for each of the yeast 26S proteasome subunits. The results are summarized from pairwise comparison experiments in which yeast cultured in light medium (L) were treated with H2O2 (1, 3, or 6 mM) and yeast cultured in heavy medium (H) were untreated. All SILAC ratios were normalized to that of Rpn11. (C) Validation of H2O2-triggered separation of the 20S core from the 19S particle. The 26S proteasome was affinity-purified with Rpn11-TAP and analyzed by quantitative Western blotting with antibodies against Rpt5 (to detect the 19S particle) and Pre10 (to detect the 20S core). The numbers below each band represent the band intensities obtained after quantitation with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. (D) Abundances of Rpn11, Rpt5, and Pre10 proteins in lysates from untreated cells or cells exposed to H2O2 (3 mM). Cdc28 was used as a loading control. (E) Confirmation of H2O2-triggered separation of the 20S core from the 19S particle in cells containing Rpn1-HB or Rpn10-HB. The 26S proteasome was affinity-purified (IP) from cells containing Rpn1-HB or Rpn10-HB by binding to streptavidin beads. The bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against Rpt5 (to detect the 19S particle) and Pre10 (to detect the 20S core). Data are from three experiments.

One population of Rpn11-TAP cells was grown in “light medium” containing 12C614N4-Arg and 12C614N2-Lys and was treated with H2O2, whereas the other population of the same cells was grown in “heavy medium” containing 13C615N4-Arg and 13C615N2-Lys and was used as a control, untreated population. Three independent pairwise comparison experiments were performed in which three concentrations of H2O2 (1, 3, and 6 mM) were applied and the treated sample was compared directly with the untreated control in each data set. The SILAC ratios of all of the proteasome subunits were calculated on the basis of the monoisotopic peak intensities of their tryptic peptides, which represent the relative changes in their abundance between the two compared samples (Fig. 1B). All of the 19S subunits, including 13 Rpn subunits [Rpn1 to Rpn3, Rpn5 to Rpn13, and Rpn15 (also known as SEM1)] and six Rpt subunits (Rpt1 to Rpt6) had SILAC ratios (L/H) of ∼1, indicating that the relative abundances of these individual 19S subunits in the purified samples were unaffected by H2O2-induced stress (Fig. 1B). However, the SILAC ratios of all 14 of the 20S proteasome subunits decreased substantially from ∼0.9 to ∼0.15 in a dose-dependent manner, demonstrating that H2O2-induced stress resulted in dissociation of the 20S core from the 19S regulatory particle (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained in a label-switch experiment, in which the treated cells were grown in heavy medium, whereas the untreated cells were grown in light medium. The detailed results are summarized in table S1.

To validate the structural changes determined by SILAC-MS, we affinity-purified yeast proteasome complexes from the Rpn11-TAP strain and analyzed them by quantitative Western blotting. Specific antibodies against Rpt5 (a 19S subunit) or Pre10 (a 20S subunit) were used to quantify the changes in their relative abundance. Consistent with the mass spectrometric analysis, the abundance of Pre10 in the purified 26S proteasome complex decreased with increasing oxidative stress, whereas the abundance of Rpt5 remained unchanged (Fig. 1C). In addition, the abundance changes determined by quantitative Western blotting correlated well with those determined by SILAC-MS (Fig. 1B). Examination of whole-cell lysates showed that H2O2 had no substantial effect on the abundances of Rpn11, Rpt5, and Pre10 (Fig. 1D). This is in agreement with SILAC-based quantitation of the total amounts of 19S (table S1) and 20S (table S2) components, which showed no substantial changes in abundance. Godon et al. previously identified H2O2-induced changes in the abundances of a few selected proteasome subunits by two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis and autoradiography (27). It is unclear whether these differences for the selected subunits between our study and that of Godon et al. are due to the different experimental conditions used or whether they reflect strain-specific behavior.

To further confirm the oxidative stress–induced structural change in the 26S proteasome and to exclude any effects that were due to the nature of the subunits, affinity tags, or both, we performed affinity purification and Western blotting experiments with two additional hexahistidine– biotin (HB)–tagged 19S subunits, Rpn1 and Rpn10, as baits (Fig. 1E) (28). Dissociation of the 19S and 20S components was evident after treatment with H2O2, which agrees well with those results obtained in experiments with Rpn11-TAP (Fig. 1, B and C). Together, these results demonstrate that oxidative stress induces the disassembly of the 26S proteasome complex.

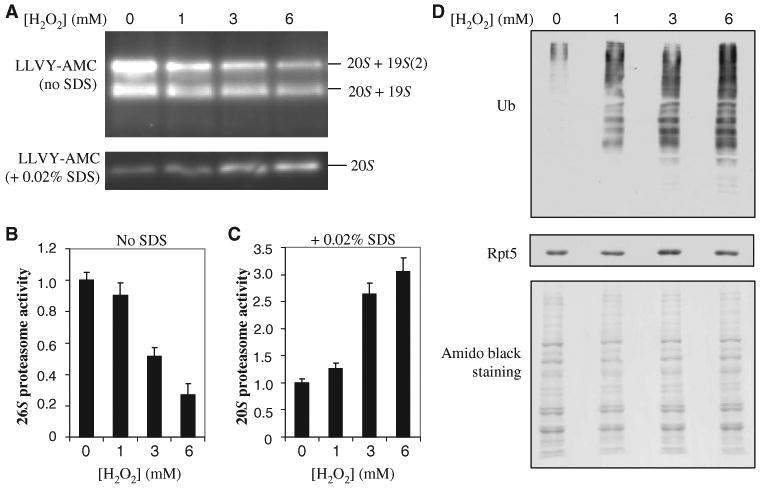

Oxidative stress inhibits the proteolytic activity of the 26S proteasome and causes the accumulation of ubiquitinated substrates

To determine the biological consequence of H2O2-induced structural changes in the 26S proteasome, we separated different species of proteasomes present in total yeast lysates by native gel electrophoresis and measured their chymotrypsin-like activities with a fluorogenic peptide substrate (8). The 19S particle is required for activation of the 20S core, but the activity of the 20S complex can be measured in vitro by the addition of detergents. We measured the in-gel proteasome activity at the migration position of 26S proteasomes in the absence of SDS. H2O2 substantially reduced the activity of the 26S proteasome (Fig. 2A). In contrast, we examined the activity of the 20S core in the presence of SDS and found that it increased considerably in cells exposed to H2O2 compared to that in control cells (Fig. 2A), suggesting that more free 20S core was present in the cell lysates of H2O2-treated cells than in those of untreated cells. We then quantified the changes in the activities of the 26S and 20S proteasomes (Fig. 2, B and C). The activity of the 26S proteasome decreased by ∼50% in cells treated with 3 mM H2O2 compared to that in untreated cells, which agrees well with the SILAC-MS and quantitative Western blotting data (Fig. 1, B and C). The reduction in the activity of the 26S proteasome in cells treated with H2O2 was further confirmed by an in-solution activity assay. Because the abundances of the proteasome subunits did not change after exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 1D), the decrease in the activity of the 26S proteasome and the corresponding increase in the activity of the 20S proteasome were likely due to the observed separation of the 19S particle from the 20S core (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Effects of H2O2-induced dissociation of the 20S core from the 19S particle. (A) Proteasome activities after oxidative stress. Lysates from cells treated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 were resolved by native gel electrophoresis. Chymotrypsin-like activity was measured with a native gel overlay assay with the fluorogenic peptide substrate SUC-LLVY-AMC in the absence or presence of 0.02% SDS to assay the 26S and 20S proteasomes, respectively. (B and C) Quantitation of the proteasome activities detected in (A) with a Fuji LAS400 imager for (B) 26S proteasomes and (C) 20S proteasomes. (D) Detection of total ubiquitin conjugates after H2O2-induced stress by Western blotting analysis with an antibody against ubiquitin. Equivalent loading was determined by analysis of Western blots with an antibody against Rpt5 and by staining of the membrane with amido black. Data are from three experiments.

Degradation of ubiquitinated proteins is thought to require the intact 26S proteasome. On the basis of our results, we expected that ubiquitinated proteins would accumulate in response to H2O2-induced stress because of a loss of 26S activity. To test this, we analyzed lysates from treated and untreated cells by Western blotting with antibodies against ubiquitin. Indeed we observed a substantial increase in the amount of total ubiquitinated proteins in cells exposed to H2O2 compared to that in untreated cells (Fig. 2D). This is consistent with inhibition of 26S activity during oxidative stress, but we cannot exclude the possibility that the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins was the consequence of induced ubiquitination combined with decreased proteolysis or because of inhibition of deubiquitination.

Ecm29 is recruited to the 19S particle during oxidative stress

To better understand the regulatory mechanism of oxidative stress–induced inhibition of the 26S proteasome, we next investigated whether changes in proteasome-interacting proteins (PIPs) correlated with its disassembly. Although we identified and quantified several PIPs (table S2), only one of them, Ecm29, displayed a substantial, dose-dependent recruitment to the 19S particle in response to H2O2-induced stress. This is illustrated by the SILAC-MS spectra of one exemplary Ecm29-derived tryptic peptide, which demonstrates changes in its relative abundance in purified 26S proteasome complexes upon treatment with various concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 3A). The SILAC ratios of Ecm29 (table S3) indicated a >15- and a 52-fold increase in the extent of Ecm29 binding to the 19S proteasome after a 30-min incubation of cells with 3 or 6 mM H2O2, respectively. Ecm29 not only had substantially increased SILAC ratios, but was also identified with an increased number of unique peptides (from 9 to 75) with increased H2O2 concentration, which further supports the observed substantial changes in abundance. These results suggest that considerable amounts of Ecm29 were recruited to Rpn11 -containing complexes upon treatment with H2O2. The results from the mass spectrometric analysis were confirmed by quantitative Western blotting analysis of purified proteasome complexes and the detection of hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged Ecm29 (Fig. 3B). To exclude the possibility that the enrichment of Ecm29 in the 19S particle was a result of oxidation-induced increases in protein abundance, we analyzed whole-cell lysates by Western blotting. We did not observe any change in the abundance of Ecm29 protein upon treatment with H2O2, demonstrating that Ecm29 was specifically enriched on the 19S particle during H2O2-induced stress (Fig. 3B).

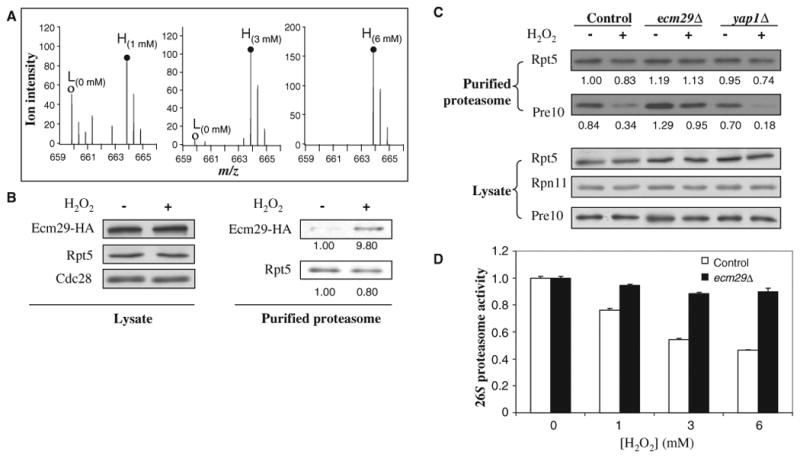

Fig. 3.

Ecm29 recruitment and its effect on the dissociation of the yeast 26S proteasome. (A) Enrichment of Ecm29 in purified 26S proteasome complexes as determined by SILAC-MS analysis. MS spectra of one representative Ecm29 tryptic peptide pair [MH22+ 659.86, VNNASINTSATVK versus MH22+ 663.86, VNNASINTSATVK (label: 13C615N2)]. (○), untreated (L); (●), treated (H). The SILAC ratios (H/L) of Ecm29 were 1.6, 17.3, and 43.7 when the cells cultured in heavy medium were treated with H2O2 (1, 3, and 6 mM) in comparison to the untreated cells cultured in light medium. Abbreviations for the amino acids are as follows: A, Ala; I, Ile; K, Lys; N, Asn; S, Ser; T, Thr; and V, Val. (B) Validation of H2O2-triggered enrichment of Ecm29 in the purified 19S particle by quantitative Western blotting. The abundances of Ecm29-HA proteins in lysates and bound to purified proteasomes from untreated and treated cells were measured by Western blotting with antibodies against the HA tag. Cells were treated with H2O2 (3 mM). (C) Roles of Ecm29 and Yap1 in the oxidative stress–induced disassembly of the 26S proteasome as determined by quantitative Western blotting. Wild-type cells and ecm29Δ or yap1Δ cells containing Rpn11-TAP were untreated or treated with H2O2 (3 mM) for 30 min. The purified proteasome complexes were analyzed by quantitative Western blotting with antibodies against Rpt5 (a 19S subunit) and Pre10 (a 20S subunit) and an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. The number below each band represents its intensity. (D) Effect of ECM29 deletion on the activity of the 26S proteasome. Wild-type and ecm29Δ cells grown to mid-log phase were left untreated or treated with H2O2 (1, 3, or 6 mM) for 30 min, and cell lysates were analyzed for chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity. Data are from three experiments.

We used a similar SILAC-MS–based approach, with the 20S subunit Pre10 as the bait, to identify proteins that were recruited or dissociated from the 20S core upon oxidative stress. We did not detect any substantial changes in the 20S core other than loss of the 19S particle. The amount of Ecm29 that was bound to the 20S core remained unchanged during H2O2-induced stress (fig. S1 and table S2), which suggests that a small fraction of Ecm29 was primarily associated with the 20S core and that a different pool of Ecm29 was recruited to the 19S particle during oxidative stress. Together, these data suggested that the recruitment of Ecm29 to the 19S particle correlated with the disassembly of the 26S proteasome, which implied that the selective enrichment of Ecm29 on the 19S particle might either induce disassembly of the 26S proteasome or prevent its reassembly.

Ecm29 regulates the composition and function of the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress

Differential binding of Ecm29 to the 19S particle was particularly interesting because Ecm29 is thought to be involved in modulating the dynamics of the yeast 26S proteasome (29–31). We hypothesized that the recruitment of Ecm29 was directly involved in the disassembly of the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress. To test this idea, we monitored the dissociation of the 20S core from the 19S particle in wild-type and in ecm29Δ cells (which are deficient in Ecm29 protein) by quantitative Western blotting (Fig. 3C). We purified proteasomes from Rpn11-TAP–expressing strains and monitored the 20S and 19S complexes by detecting the 20S subunit Pre10 and the 19S subunit Rpt5. Unstressed wild-type and ecm29Δ cells had comparable amounts of intact 26S complexes (Fig. 3C). This was further confirmed by the SILAC-MS approach, through which we did not detect any substantial changes in the composition of the 26S complexes purified from wild-type or ecm29Δ cells (fig. S2 and table S4). Thus, deletion of ECM29 has no substantial effect on the composition and structure of the 26S proteasome complex in unstressed cells in the genetic background used. Ecm29 was therefore not essential for the integrity of the 26S proteasome complex under normal growth conditions. As expected substantially less 20S core copurified with the 19S particle when wild-type cells were exposed to H2O2. Dissociation of the 19S particle from the 20S core during oxidative stress was almost completely blocked in ecm29Δ cells, as shown by quantitative Western blotting (Fig. 3C) and SILAC-MS analysis (fig. S2 and table S5), demonstrating that Ecm29 was required for the disassembly of the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress.

The yeast transcription factor Yap1 plays a key role in sensing oxidative stress and coordinating the cellular response (32). To determine whether the Yap1 pathway was involved in regulating the 26S proteasome upon H2O2-induced stress, we analyzed changes in the 26S proteasome during oxidative stress in yap1Δ cells. Dissociation of the 26S complex in yap1Δ cells was comparable to that observed in wild-type cells, demonstrating that the Yap1 pathway did not regulate proteasome integrity during oxidative stress (Fig. 3C). In addition, deletion of YAP1 did not affect the H2O2-induced recruitment of Ecm29 to the 19S particle (fig. S3).

Our results demonstrated that Ecm29 was required for stress-induced disassembly of the 26S complex and suggested that the observed reduction in the activity of the 26S proteasome in response to H2O2 should be eliminated in ecm29Δ cells. To this end we first used an in-solution assay to compare the activities of the 26S proteasomes in yeast extracts prepared from wild-type and ecm29Δ cells during oxidative stress (Fig. 3D). Proteasome activity was comparable in unstressed cells. Oxidative stress inhibited the activity of the 26S proteasome in wild-type cells, but deletion of ECM29 substantially prevented such loss of activity (Fig. 3D). This requirement for Ecm29 in oxidative stress–induced inhibition of the activity of the 26S proteasome was further confirmed by an in-gel activity assay of the 20S and 26S proteasomes in the presence or absence of SDS, respectively (fig. S4). These results are consistent with the role of Ecm29 in disrupting the integrity of the 26S proteasome. Together, our data suggest that Ecm29 is required for the efficient dissociation of the 19S particle from the 20S core in response to H2O2, and that regulation of proteasomes involves a stress pathway that is distinct from Yap1-regulated events.

Disassembly of the 26S proteasome is required for the response to oxidative stress

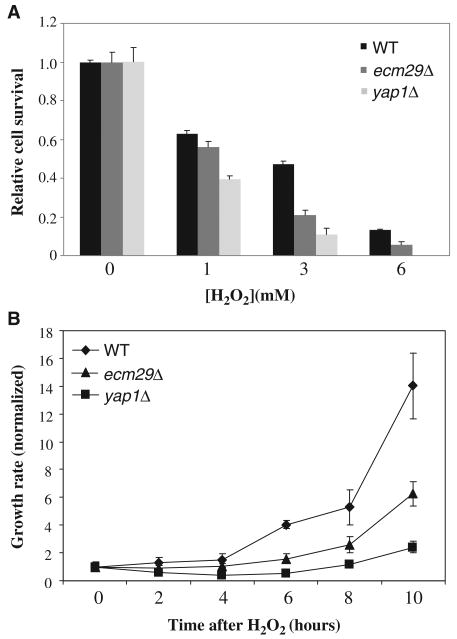

To determine whether dissociation of the 19S particle from the 20S core was important for the cellular response to H2O2 stress, we compared the viability of wild-type and ecm29Δ cells. We analyzed yap1Δ cells, which are deficient in the primary response pathway to oxidative stress, in parallel as a control. We exposed cells to various concentrations of H2O2 for 30 min and determined the number of cells that could form colonies (Fig. 4A). Deletion of ECM29 resulted in modest but substantial hypersensitivity to H2O2-induced stress, compared to that in wild-type cells; however, ecm29Δ cells required a much longer time to form colonies after acute H2O2-induced stress than did wild-type cells, even though the doubling times of wild-type and ecm29Δ cells were similar. We speculated that Ecm29-dependent disassembly of the 26S proteasome might be critical particularly during the recovery from acute oxidative stress. To this end we monitored cells as they reentered the cell cycle after H2O2-induced stress. Cells were exposed to 3 mM H2O2 for 30 min, washed to remove the oxidant, incubated in fresh medium, and plated after 2-hour intervals to enable us to monitor cell division. Only viable cells were considered to compensate for the differences in viability of the mutant strains under H2O2-induced stress conditions. Reentry into the cell division cycle was delayed for several hours in ecm29Δ cells compared to that in wild-type cells, which suggested that disassembly of the 26S proteasome was critical for recovery from oxidative stress (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Ecm29 is required for the cellular response to H2O2. (A) Wild-type (WT), ecm29Δ, and yap1Δ cells containing Rpn11-TAP were grown to mid-log phase and were left untreated or treated with H2O2 (1, 3, or 6 mM) for 30 min at 30°C. Cells were plated onto YEPD and colonies were counted after 3 to 4 days of incubation at 30°C. (B) Growth recovery assay. Cells were treated with H2O2 (3 mM) as in (A) and were diluted 10,000-fold in prewarmed YEPD. Equal volumes of cultures were plated onto YEPD at the indicated times to determine growth rates by colony counting. Only viable cells were considered, because cell numbers were normalized to colony-forming cells at the zero time point. Data are from three experiments.

H2O2 stress–induced disassembly of the 26S proteasome is conserved in human cells

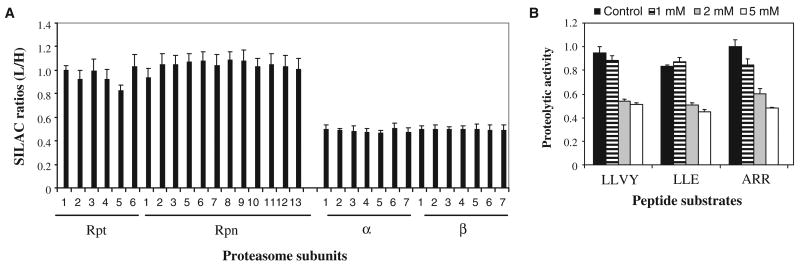

To determine whether disassembly of the proteasome during oxidative stress was a conserved regulatory mechanism in eukaryotes, we used our proteomic approach to examine structural changes in the human proteasome. We purified proteasomes from human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells stably expressing hexahistidine-TEV-BH (HTBH)–tagged Rpn11 (25) before and after exposure to 2 mM H2O2 for 30 min. The relative abundances of the proteasome subunits in the purified samples from untreated and treated cells were determined on the basis of their SILAC ratios. Similar to the results that we obtained from our experiments in yeast, all of the 19S proteasome subunits were unchanged in abundance, with SILAC ratios of ∼1.0 (Fig. 5A). All of the 20S subunits had substantially reduced SILAC ratios (∼0.5), indicating that oxidative stress induced the disassembly of about half of the 26S proteasomes. This result was further confirmed by Western blotting analysis (fig. S5). Consistent with the proteomics data, the proteolytic activity of the 26S proteasome was substantially reduced in H2O2-treated HEK 293 cells compared to that in untreated cells, both when analyzed in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 5B) or after purification of proteasomes with Rpn11-HTBH. Collectively, these results suggest that dissociation of the 26S proteasome complex in response to H2O2 stress is a conserved cellular response in eukaryotes.

Fig. 5.

Disassembly of the human 26S proteasome as a result of H2O2-induced stress. (A) SILAC (L/H) ratios for subunits of the human 26S proteasome. 26S proteasomes were purified from HEK 293 cells stably expressing HTBH-tagged Rpn11. L, cells treated with H2O2 (2 mM); H, untreated control cells. (B) The proteasomal proteolytic activities in cells treated with H2O2 (1, 2, or 5 mM) for 30 min as determined by in-solution assay. Three fluorogenic peptide substrates were used: SUC-LLVY-AMC to detect chymotrypsin-like activity; SUC-LLE-AMC to detect peptide hydrolase activity; and SUC-ARR-AMC to detect trypsin-like activity. The activity was normalized to that of Rpt6 (a 19S subunit) in each sample. Data are from three experiments.

Discussion

We used affinity purification and SILAC-based quantitative MS to investigate the effects and underlying mechanisms of oxidative stress on the 26S proteasome. Here, we present direct evidence that H2O2-induced oxidative stress caused dissociation of the 20S core from the 19S particle, thus leading to disassembly of the 26S proteasome. In addition, we demonstrated that the PIP Ecm29 was a key regulator of the 26S proteasome structure in response to H2O2-induced stress in yeast. Ecm29 modulated assembly of the 26S proteasome by tethering the 20S core to the 19S particle, and it is thought to stabilize the 20S-19S interaction during affinity purification in the absence of ATP (29, 30). Ecm29 also functions as an adaptor protein that enables the conversion of incompletely mature assemblies of catalytic and regulatory particles to mature proteasomes (31). Our results describe an additional function for Ecm29 in the cellular response to oxidative stress. Together, these results suggest that Ecm29 is a key component that controls the assembly and disassembly of the 26S proteasome and that the abundance of Ecm29 in the 26S proteasome complex may be critical for these functions. It has been noted that the interaction between Ecm29 and the proteasome is salt-sensitive (29). We found that H2O2-induced stress did not change the salt-labile nature of the interaction between Ecm29 and the proteasome. Furthermore, the relative change in the abundance of Ecm29 in 19S proteasomes purified from untreated and H2O2-treated cells was independent of the salt concentrations used in the purification process (fig. S6). How Ecm29 is recruited to the 19S particle during oxidative stress is unknown. Oxidative stress–induced protein modifications that lead to the recruitment of Ecm29 could play a role and are the subject of future studies.

We demonstrated that H2O2-induced stress inhibited the activity of the 26S proteasome in a concentration-dependent manner. Although dysfunction of the activity of the 26S proteasome in response to oxidative stress has been reported in other cell systems (21–23, 33), the underlying mechanism is not well understood. Here, we showed that the H2O2 stress–induced attenuation of the proteasome activity was due to the Ecm29-dependent disassembly of the 26S proteasome complex. A number of studies have suggested that degradation of oxidized proteins occurs by a ubiquitin- and ATP-independent mechanism (18, 33, 34), implying that such degradation is more likely dependent on the 20S core and not on the 26S proteasome. This idea is based on the observation that cells deficient in ubiquitin-conjugating activity degrade oxidized proteins at near-normal rates in vivo (33) and that exposure of hydrophobic patches in oxidatively damaged and unfolded proteins triggers their recognition by the 20S proteasome for degradation in vitro (18). Therefore, dissociation of the 20S core from the 19S particle during oxidative stress could increase the capacity of the cells to remove oxidatively damaged proteins.

Yeast mutants defective in the assembly of the 26S proteasome are more resistant to H2O2 exposure than are wild-type cells, and they degrade oxidized proteins more effectively, which is likely because of the increased fraction of the 20S core that results from the reduced assembly of 26S proteasomes (35). Similarly, proteasome mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana with impaired 26S proteasome activity have an increased capacity for ubiquitin-independent proteolysis involving the 20S core and are more tolerant to oxidative stress than are wild-type plants (36). Furthermore, we found that disassembly of the 26S proteasome was reversible upon removal of the oxidant (fig. S7), thus restoring the normal proteolytic activities of the proteasome. This is consistent with studies that showed that oxidation-triggered loss of ATP- and ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis by the 26S proteasome was restored after a recovery period (21, 22). Disassembly of the 26S proteasome may increase the abundance of the 20S proteasome and thus enhance cellular defense against oxidative stress. However, how the 20S core is activated to degrade oxidized proteins is unclear. An alternative biological role for the inhibition of 26S activity during acute oxidative stress could be to provide more time for protein repair to reduce demand on the cellular synthesis machinery. Regardless of what the exact biological role of 26S inhibition in the oxidative stress response might be, our data show that dissociation of the 19S particle from the 20S core is the underlying molecular reason for these observations, and that disassembly of the 26S proteasome is essential for the cellular response to oxidative stress.

In summary, we found that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway could be subjected to global inhibition, and we identified the 26S proteasome complex as a target of this regulation in yeast and human cells. We demonstrated that the yeast PIP Ecm29 was required for H2O2-induced dissociation of the 19S particle from the 20S core, and we showed that this process was important for cell survival, particularly for recovery from oxidative stress. The Ecm29-dependent dissociation of the proteasome was independent of the Yap1 pathway, suggesting that additional defense mechanisms in response to oxidative stress are important for cell survival and stress recovery. Disassembly of the 26S proteasome also contributes to inhibition of the proteasome during aging in Drosophila melanogaster (37) and the stationary phase in yeast cells (38). Therefore, disassembly may be a general regulatory mechanism of the 26S proteasome under different stress conditions.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

ImmunoPure streptavidin, horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody, and SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate were from Pierce Biotechnology. Sequencing-grade trypsin was purchased from Promega Corp. Endoproteinase Lys-C was from WAKO chemicals. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (deficient in lysine and arginine) was obtained from Fisher Scientific. 13C615N4-Arg and 13C615N2-Lys were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. 12C614N4-Arg and 12C614N2-Lys were obtained from Sigma. Rabbit IgG antigen affinity gel was from MP Biomedicals LLC. The proteasome substrates SUC-LLVY-AMC, SUC-LLE-AMC, and SUC-ARR-AMC were purchased from Boston Biochem. Antibodies against yeast Rpt5 and Pre10 were from Biomol International. Peroxidase anti–peroxidase (PAP) soluble complex antibody was purchased from Sigma. Alexa Fluor 680–conjugated goat antibody against mouse IgG (H+L) was from Invitrogen. IRDye 800CW goat antibody against rabbit IgG was from LI-COR Biosciences. All other general chemicals for buffers and culture media were purchased from Fisher Scientific or VWR International.

Yeast strains and culture conditions

The genotypes of the yeast strains used in this study are listed in table S1. All strains used in this study were isogenic to 15DaubΔ, bar1Δura3Δns, a derivative of BF264-15D. Epitope-tagged genomic loci and gene deletions were generated with a standard single-step polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based strategy. Strains were cultured in YEPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose). For the MAP-SILAC experiments, arginine and lysine auxotroph strains (arg4Δ lys2Δ) expressing TAP-tagged Rpn11 in amounts similar to that of the endogenous protein (Rpn11-TAP∷Kan, Pep4∷URA3, Lys∷ZEO, Arg∷HYG) were grown in synthetic complete medium supplemented with 13C615N4-Arg (30 mg/liter) and 13C615N2-Lys (100 mg/liter) (heavy medium) or with 12C614N4-Arg (30 mg/liter) and 12C614N2-Lys (100 mg/liter) (light medium) at 30°C until the culture reached an absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of ∼0.5. Yeast cells grown in light medium were treated with 1, 3, or 6 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 30°C, whereas yeast cells grown in heavy medium were untreated. In the label-switch experiments, light labeled yeast cells grown in light medium were left untreated, whereas cells cultured in heavy medium were treated with different concentrations of H2O2. Proteasome complexes from treated and untreated cells were purified separately and then mixed for subsequent digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis.

Affinity purification of the yeast 26S proteasome

Cells expressing Rpn11-TAP or Pre10-TAP were cultured as described earlier. Cell pellets from 100 ml of culture were collected by filtration and lysed in buffer A [100 mM sodium chloride, 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 × protease inhibitor (Roche), 1 × phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, and 0.5% NP-40]. After the removal of cellular debris, the lysates were incubated with IgG affinity gel for 1 hour at 4°C Proteins bound to the IgG affinity gel were washed with 50 bed volumes of buffer A and 30 bed volumes of TEV protease buffer (TEB) [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM ATP]. The 26S proteasome complex was eluted by incubation with 1% TEV protease in TEB buffer for 1 hour at 30°C.

Proteasome proteolytic activity assay

The proteolytic activities of the yeast proteasomes were measured by native gel overlay assay as described previously (39). Briefly, equal amounts of lysates from each sample were resolved by 4% native gel electrophoresis for 5 hours at 90 V and 4°C The gel was incubated with the fluorogenic peptide substrate SUC-LLVY-AMC for 30 min at 37°C with or without 0.02% SDS. The images were visualized with the Fujifilm LAS400 imager. In-solution proteolytic activity assays for yeast and mammalian proteasomes were performed with the fluorogenic peptide substrates SUC-LLVY-AMC, SUC-LLE-AMC, and SUC-ARR-AMC, as described previously (39).

Mammalian cell culture and purification of human 26S proteasomes

HEK 293 cells stably expressing Rpn11-HTBH (25) were used for quantitative analysis of proteasome composition, as described previously (26). Cells were treated with 1, 2, or 5 mM H2O2 at 37°C in cell culture medium for 30 min at 95% confluence. Affinity purification of the 26S proteasome was achieved by binding to streptavidin beads followed by elution by cleavage with TEV (25). For MAP-SILAC experiments (26), the treated and untreated samples were purified separately and then mixed together for subsequent digestion with trypsin and analysis by MS to avoid subunit exchange during the purification.

Quantitative Western blotting analysis

The purified proteasome complexes were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and analyzed by Western blotting. To probe yeast proteasomes, we used an antibody against Rpt5 (at a 1:250,000 dilution) followed by an IRDye 800CW goat antibody against rabbit antibody (at a 1:10,000 dilution), as well as an antibody against Pre10 (1:1000 dilution) followed by Alexa Fluor 680–conjugated goat antibody against mouse IgG (H+L) (1:10,000 dilution). The protein bands were detected and quantified with an Odyssey infrared scanning system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Protein identification and quantification by MS

The purified proteasome complexes were digested in solution with Lys-C/trypsin and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described previously (25). For 2D LC-MS/MS, the peptide digests were first separated by strong cation exchange chromatography and the resultant fractions were analyzed by LC-MS/MS with a nanoLC system (Eksigent Inc.) coupled with a linear ion trap (LTQ) Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp.) (40). Protein identification and quantitation were achieved through database searching with the developmental version (5.1.7) of Protein Prospector at University of California, San Francisco. Proteins that exhibited oxidative stress–induced changes in their interactions with Rpn11-containing proteasome complexes had SILAC ratios that were either >1 or <1, whereas proteins whose interactions with the proteasome were unchanged during treatment had SILAC ratios close to 1. The SILAC ratios of all of the proteasome subunits were calculated on the basis of monoisotopic peak intensities of their tryptic peptides, which represented changes in their relative abundances in the two samples that were compared (26).

Cell viability assay

Yeast strains were cultured in YEPD medium at 30°C to mid-log phase. Cultures were then either left untreated or treated with 1, 3, or 6 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 30°C in triplicate sets. Cultures were diluted 100-fold in YEPD and serial dilutions were plated onto YEPD plates. Plates were incubated at 30°C and colonies were counted after 3 to 4 days of incubation.

Recovery assays

Yeast strains were cultured in YEPD medium at 30°C to mid-log phase and treated with 3 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 30°C in triplicate sets. Cultures were then diluted 10,000-fold in fresh, prewarmed (30°C) YEPD to stop oxidative stress. Cells were incubated at 30°C for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 hours, and equal volumes of the cultures were plated onto YEPD plates after the indicated time period. Plates were incubated for 3 to 4 days at 30°C, colonies were counted and averages were calculated for each time point. The averages were then normalized to the 0-min time point to compensate for differences in the cell viabilities of the mutant strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Huang and Kaiser laboratories for their help during this study, especially Y. Yang, C. Yu, P. Pan, and K. Flick. We are grateful to S. Elsasser and D. Finley at Harvard Medical School for their help with the proteasome proteolytic activity assay. We thank R. Aphasizhev for his help with the Fujifilm LAS400.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants (GM-74830, GM-74830AS1, and UCLA U19 seed grant/UCLA-43510 to LH. and GM-66164 and GM66164AS1 to P.K.).

Footnotes

Author contributions: X.W. participated in experimental design, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, generated all of the figures and tables (except for Fig. 4), and contributed to the writing of Materials and Methods; J.Y. performed the experiments for Fig. 4; P.K. and LH. designed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: A molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickart CM, Cohen RE. Proteasomes and their kin: Proteases in the machine age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glickman MH, Rubin DM, Coux O, Wefes I, Pfeifer G, Cjeka Z, Baumeister W, Fried VA, Finley D. A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eiF3. Cell. 1998;94:615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Finley D. Proteasome-associated proteins: Regulation of a proteolytic machine. Biol Chem. 2005;386:725–737. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma R, Oania R, Graumann J, Deshaies RJ. Multiubiquitin chain receptors define a layer of substrate selectivity in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell. 2004;118:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elsasser S, Finley D. Delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to protein-unfolding machines. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:742–749. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma R, Aravind L, Oania R, McDonald WH, Yates JR, III, Koonin EV, Deshaies RJ. Role of Rpn11 metalloprotease in deubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome. Science. 2002;298:611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubiel W, Pratt G, Ferrell K, Rechsteiner M. Purification of an 11 S regulator of the multicatalytic protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22369–22377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma CP, Slaughter CA, DeMartino GN. Identification, purification, and characterization of a protein activator (PA28) of the 20 S proteasome (macropain) J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10515–10523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao X, Li J, Pratt G, Wilk S, Rechsteiner M. Purification procedures determine the proteasome activation properties of REGγ (PA28γ) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;425:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ustrell V, Hoffman L, Pratt G, Rechsteiner M. PA200, a nuclear proteasome activator involved in DNA repair. EMBO J. 2002;21:3516–3525. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F, Hu Y, Huang P, Toleman CA, Paterson AJ, Kudlow JE. Proteasome function is regulated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase through phosphorylation of Rpt6. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22460–22471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Guerrero C, Kaiser P, Huang L. Proteomics of proteasome complexes and ubiquitinated proteins. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4:649–665. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes AV, Zong C, Edmondson RD, Li X, Stefani E, Zhang J, Jones RC, Thyparambil S, Wang GW, Qiao X, Bardag-Gorce F, Ping P. Mapping the murine cardiac 26S proteasome complexes. Circ Res. 2006;99:362–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237386.98506.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung T, Grune T. The proteasome and its role in the degradation of oxidized proteins. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:743–752. doi: 10.1002/iub.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20S proteasome. Biochimie. 2001;83:301–310. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breusing N, Grune T. Regulation of proteasome-mediated protein degradation during oxidative stress and aging. Biol Chem. 2008;389:203–209. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friguet B. Oxidized protein degradation and repair in ageing and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2910–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinheckel T, Sitte N, Ullrich O, Kuckelkorn U, Davies KJ, Grune T. Comparative resistance of the 20S and 26S proteasome to oxidative stress. Biochem J. 1998;335(Pt 3):637–642. doi: 10.1042/bj3350637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinheckel T, Grune T, Davies KJ. The measurement of protein degradation in response to oxidative stress. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;99:49–60. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang F, Taylor A. Oxidative stress and recovery from oxidative stress are associated with altered ubiquitin conjugating and proteolytic activities in bovine lens epithelial cells. Biochem J. 1995;307:297–303. doi: 10.1042/bj3070297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shang F, Gong X, Taylor A. Activity of ubiquitin-dependent pathway in response to oxidative stress. Ubiquitin-activating enzyme is transiently up-regulated. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23086–23093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Chen CF, Baker PR, Chen PL, Kaiser P, Huang L. Mass spectrometric characterization of the affinity-purified human 26S proteasome complex. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3553–3565. doi: 10.1021/bi061994u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Huang L. Identifying dynamic interactors of protein complexes by quantitative mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:46–57. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700261-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godon C, Lagniel G, Lee J, Buhler JM, Kieffer S, Perrot M, Boucherie H, Toledano MB, Labarre J. The H2O2 stimulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22480–22489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tagwerker C, Flick K, Cui M, Guerrero C, Dou Y, Auer B, Baldi P, Huang L, Kaiser P. A tandem affinity tag for two-step purification under fully denaturing conditions: Application in ubiquitin profiling and protein complex identification combined with in vivo cross-linking. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:737–748. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500368-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leggett DS, Hanna J, Borodovsky A, Crosas B, Schmidt M, Baker RT, Walz T, Ploegh H, Finley D. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol Cell. 2002;10:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleijnen MF, Roelofs J, Park S, Hathaway NA, Glickman M, King RW, Finley D. Stability of the proteasome can be regulated allosterically through engagement of its proteolytic active sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1180–1188. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann A, Niewienda A, Jechow K, Janek K, Enenkel C. Ecm29 fulfils quality control functions in proteasome assembly. Mol Cell. 2010;38:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaunay A, Isnard AD, Toledano MB. H2O2 sensing through oxidation of the Yap1 transcription factor. EMBO J. 2000;19:5157–5166. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shringarpure R, Grune T, Mehlhase J, Davies KJ. Ubiquitin conjugation is not required for the degradation of oxidized proteins by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:311–318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grune T, Reinheckel T, Davies KJ. Degradation of oxidized proteins in mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1997;11:526–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inai Y, Nishikimi M. Increased degradation of oxidized proteins in yeast defective in 26 S proteasome assembly. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;404:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurepa J, Smalle JA. Structure, function and regulation of plant proteasomes. Biochimie. 2008;90:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vernace VA, Arnaud L, Schmidt-Glenewinkel T, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Aging perturbs 26S proteasome assembly in Drosophila melanogaster. FASEB J. 2007;21:2672–2682. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6751com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajorek M, Finley D, Glickman MH. Proteasome disassembly and downregulation is correlated with viability during stationary phase. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elsasser S, Schmidt M, Finley D. Characterization of the proteasome using native gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 2005;398:353–363. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang L, Wang X, Yamoah K, Chen PL, Pan ZQ, Huang L. Characterization of the human COP9 signalosome complex using affinity purification and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4914–4925. doi: 10.1021/pr800574c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.