Abstract

Objectives: To obtain basic facts and considered opinions from health care professionals and students (nonlibrarian and librarian) about the information needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered (GLBT) health care professionals and their interactions with medical librarians.

Methods: The survey instrument was a Web-based questionnaire. A nonrandom sample of health care professionals and students (librarian and nonlibrarian) was obtained by posting messages to several large Internet electronic discussion groups (GLBT and general) and to randomly selected members of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. A total of 152 forms were analyzed with about 50% of the participants being GLBT persons.

Results: GLBT people have specific health information needs and concerns. More than 75% of medical librarians and students believed that GLBT persons have special information needs, with similar response rates by nonlibrarian health professionals and students. The delivery of services needs to be done with privacy and respect for the feelings of the patron. Major areas of need include the topics of health care proxy, cancer, adolescent depression and suicide, adoption, sexual health and practices, HIV infection, surrogate parenting, mental health issues, transgender health issues, intimate partner violence, and intimate partner loss.

Conclusions: Most GLBT health care professionals desire GLBT-friendly health information services. Making GLBT-oriented health information resources available on a library Web page and making an effort to show acceptance of cultural diversity through signs or displays would be helpful. Education directed toward instilling an awareness of GLBT persons may also be advisable. Most survey participants make some use of medical reference services and many find medical librarians to be very helpful and resourceful.

INTRODUCTION

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered (GLBT) persons are valuable members of the health care team and contribute to all fields and specialties within the health professions. No information could be found in the published library or medical literature documenting either the information needs of this specific group or the types of medical library services desired by, or provided to, these individuals. Reports about public library use and service to the general population of GLBT persons do exist [1]. Papers have also been written about the health information needs of GLBT health consumers [2–4]. For the purposes of this report, these four distinct groups are consolidated under the heading of GLBT persons. The authors acknowledge that although there are many shared characteristics among these cohorts, there are also differences, including the possibility of dissimilar information needs [5].

Unlike most minority groups, GLBT individuals are not instantly recognizable by physical features, mannerisms, clothing style, pronunciation, or other social markers. The health care provider will usually have no idea of the librarian's sexual orientation or acceptance of and comfort level with GLBT persons or issues. Likewise, the medical librarian will have no knowledge of the orientation or sexuality of the random patron, and may thus falsely believe that none of the library's patrons are GLBT persons.

A recent library literature review [6] discussing gay, lesbian, and bisexual public library services mentioned several blocks to the provision of information to these groups. Prevention of service was caused by several factors, including the homophobia of some librarians, the fear of a homophobic reaction from an unknown information specialist by a GLBT person, absence of appropriate materials, lack of display or promotion of such items, and other reasons, including lack or inappropriateness of relevant subject headings. Also mentioned was the suggestion that being “neutral” may in fact be a negative action when considering the information needs of GLBT people. Even silence concerning GLBT issues can have negative consequences, since wordlessness may be perceived, often correctly, as a tacit statement of acceptance of something that may actually be harmful or painful to someone with different cultural or sexual values [7]. Not seeing anything written about a distinct community of people in an area of scholarly literature can mean that the group is being ignored in that discipline. George Bernard Shaw wisely stated, “Silence is the most perfect expression of scorn,” and Robert Lewis Stevenson observed, “The cruelest lies are often told in silence” [8].

GLBT individuals, besides having the same basic health needs as the general population, have additional health care and access requirements because of their special sexualities and the discrimination they may face by an unknowing and sometimes hostile society. Several documents discuss these needs and the disparities in heath care that these groups face daily [9–12]. Issues such as cancer, screening tests, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, mental health, child adoption, violence and sexual assault, among others, are health topics of particular concern.

Although the Library of Congress (LC) was slow to implement changes in the language of its official subject headings to reflect common usage and current terminology of GLBT terms [13], a recent search of the Library of Congress Subject Headings reveals a variety of GLBT terminology. LC subject headings of GLBT terms cover race and nationality (African American transsexuals, Asian American bisexuals, Hispanic American gays, etc.); literature (lesbians' writings, Italian; bisexuals' writings, American; gay wit and humor, etc.); and popular culture (music by lesbian composers, gay broadcasters, bisexuality in marriage, etc.) just to name a few. There are a small number of LC subject headings that cover GBLT health care professionals (gay nurses, lesbian psychiatrists, gay librarians, lesbian librarians, etc.).

A recent search of the National Library of Medicine's (NLM) Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) uncovered a very limited number of GLBT terms. The only GLBT terms available to date are Homosexuality (introduced as a MeSH term in 1966); Homosexuality, Male, and Homosexuality, Female (introduced in 1995); and Bisexuality (introduced in 1988). There has been no new GLBT terminology established in MeSH since 1995. Since indexing is critical to information retrieval, it is hoped that appropriate terms will eventually be added to this extremely useful NLM tool.

A PubMed search of the Bulletin of the Medical Library Association using the text words “gay” and “lesbian” and the MeSH term “homosexuality” revealed only one citation [14] from the years 1965 to 2001. This was a letter to the editor calling for medical librarians to include gay materials in their collections that were gay affirming as opposed to documents written by persons with negative feelings about gayness. The same search done for the Journal of the Medical Library Association revealed no articles. There are several likely reasons for the paucity of literature on the information needs of GLBT health care professionals, including the group's status as a “hidden” or invisible population. For many researchers there may be a lack of interest in, or awareness of, persons who are GLBT. Some may believe that this area of scholarly pursuit is disreputable. There may also be fear that the investigator's career goals may be adversely affected, or that he or she will be shunned by peers. Finally, funding opportunities may be lacking for research in this area [15].

The present survey was conducted as a first step toward learning about the information needs of GLBT health care professionals. Participants were asked whether they believed that GLBT health care professionals and health consumers had special information needs and if GLBT health professionals desired GLBT- friendly information services. Some information about the interaction between GLBT patrons and medical librarians was also sought, including the ease of approach and comfort levels of persons when having to deal specifically with GLBT topics. Inquiry was also made into the provision of special health education materials to GLBT health consumers. Finally, there was also a search for data about whether knowing that the librarian was a GLBT person would influence seeking the help of that particular information specialist.

METHODS

To obtain a sampling of GLBT health professionals, members of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association were randomly selected to receive an email message inviting them to participate in the survey. The Internet electronic discussion list of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Health Science Librarians' Special Interest Group of the Medical Library Association was used to invite members of that group to participate. All other participants were sent the invitation via several large Internet electronic discussion lists, some focusing on GLBT health care professionals and students (librarian and nonlibrarian). Email invitations and general postings were sent during January of 2003. The research survey form, included in the Appendix, was designed as a series of Web pages. Anonymity of participants was respected. SurveyMonkey.com™, located in Madison, Wisconsin, was the hosting site for this survey.

RESULTS

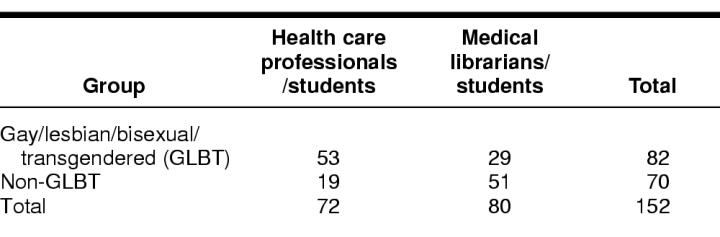

A total of 152 survey forms was completed by a population summarized in Table 1. Most participants were from the United States (126, 82.9%); with representatives from Australia (3, 2.0%); Canada (15, 9.9%); England (4, 2.6%); and other countries (Belgium, France, Ireland, New Zealand [4, 2.6%]).

Table 1 Characteristics of the survey population

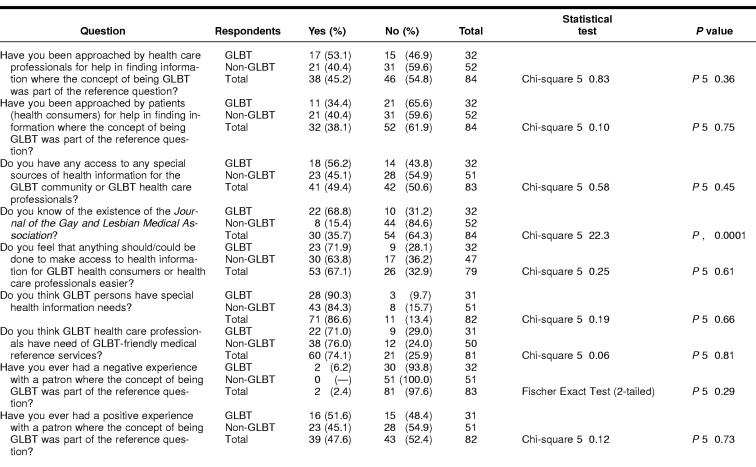

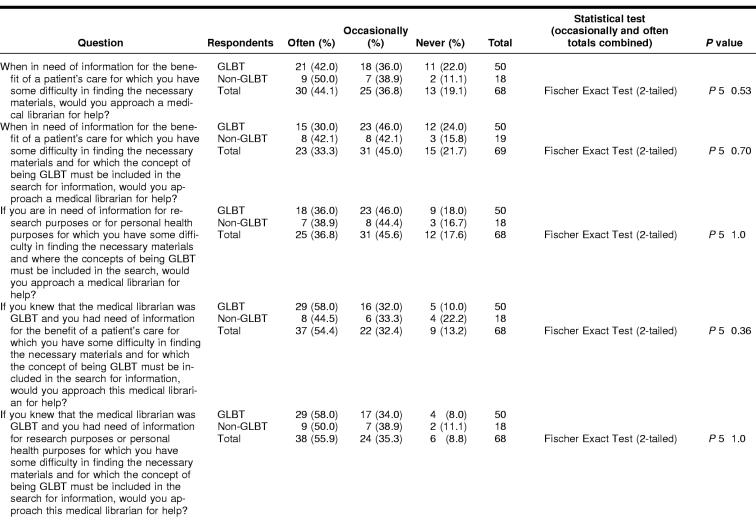

Summaries of quantitative data are presented in Tables 2 to 6. Data analysis demonstrated that there was a clear increase in the frequency of approaching a medical librarian by nonlibrarian GLBT health professionals and students when they knew that the librarian was also a GLBT person. This was demonstrated by the responses to the question: “When in need of information for the benefit of a patient's care for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials and for which the concept of being GLBT must be included in the search for information, would you approach a medical librarian?” Responses were recorded as Often = 15 (30%); Occasionally = 23 (46%); and Never = 12 (24%) for an unknown librarian, but Often = 29 (58%); Occasionally = 17 (34%); and Never = 4 (8%) for a known GLBT librarian.

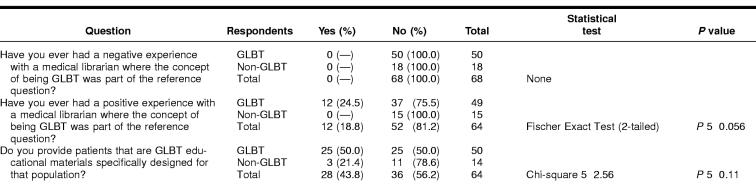

Table 2 Responses of nonlibrarian health professionals and students to yes/no questions

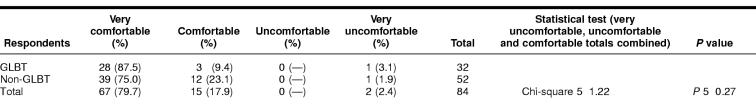

Table 6 Responses of medical librarians/students to: How comfortable are you (or would you be) if approached by a person seeking reference help where the concept of being GLBT was part of the reference question?

Respondents gave a variety of reasons why GLBT health consumers have special information needs. There were 125 responses from both librarian and nonlibrarian health care professionals and students, 74 of which were made by GLBT persons. A few felt that this group had no special information needs, but it is apparent from the large majority of answers that many health issues are of particular importance, need to be dealt with in special ways, or are unique to this population. Examples include sexual health and practices, “coming out,” health care proxies, durable power of attorney for medical decisions, visitation rights, same-sex marriage, substance abuse, breast cancer, rectal cancer, anal pap smears for men who have sex with men, adolescent depression and suicide, reproduction, adoption, HIV infection, hepatitis, immunizations, parenting, foster parenting, surrogate parenting, mental health issues, intimate partner violence, intimate partner loss, and preventative health. In addition, information specific to transgendered persons, such as the neo-vagina, hormone therapy, and special surgeries such as phalloplasty and vaginoplasty were mentioned. One librarian commented on the survey:

there's a real dearth of GLBT specific information about some serious life issues, e.g., parenting and, most especially, widowhood. Given that there are probably on the order of 2 million gay parents in the country and untold numbers of gay people who have lost partners, this absence is really quite staggering.

GLBT persons require GLBT-friendly sources of health literature and directories to special resources that can help to ameliorate problems, point to further sources of help, as well as emphasize the wholesomeness of diverse lifestyles in spite of a sometimes hostile social environment. Said one respondent:

As a consumer health information librarian in a public library, I'm often asked for guides for lesbians who want to become pregnant. I'm aware of the bias GLBT persons often face when dealing with health professionals and wish they were more comfortable approaching me for information.

Many of those surveyed pointed out that many GLBT people have been subject to such frequent negative responses from providers as well as the assumption by most providers of the heterosexuality of all patients, that they do not, for the most part, trust the clinician enough to reveal either their sexuality or special health concerns. “We are seen in a different light by health professionals—almost one of neglect. The health issues that face us are cast aside or are unreal, when they very much exist.” Several commented that most of the standard literature and information sources are heterosexually oriented and make little or no mention of the GLBT population. This bias was described as a “put off” to many GLBT people who require a different presentation of health information than what is commonly available. “GLBT persons need access to sources of health information without fear of discrimination or recrimination.”

There were 105 responses, 56 of which were made by GLBT persons, regarding reasons why GLBT health care professionals have special information needs. A few respondents felt that this population did not have special information needs. Many participants stressed that because GLBT health consumers specifically seek GLBT clinicians for their care, these health professionals need access to the most current information pertaining to the special issues of health care for this population. Many commented that the answers to a number of questions dealing with GLBT persons are either not in the standard literature or else are very hard to find, thus requiring special sources of information. These sources are needed to meet the special requirements for knowledge and training specifically necessary for working and interacting with the GLBT patient.

Not only do GLBT health care workers need information about taking care of their patients, they also require the knowledgebase necessary to help them in dealing with the persistent societal misconceptions and stigmatization that all GLBT persons routinely encounter. “In addition to needing information for GLBT patients, we sometimes need information about working/studying in a predominantly straight workplace/academic setting.” Information on dealing with the prejudice and stigmatization from peers who happen to be non-GLBT is also a perceived special need. One person stated: “Prejudice requires special information needs.” Another said that confidentiality and trust are important issues for those GLBT professionals who are not “out” to the general medical or hospital community and are unwilling to communicate information needs when doing so might reveal aspects of their own sexuality or interest in treating GLBT patients. One person with experience at a major academic medical center mentioned that there is an overwhelming concern among many providers and students about revealing sexual orientation and the likely impact it might have on careers, confirming that privacy and confidentiality are extremely important factors to consider when serving this group. Medical students may feel particularly vulnerable in seeking help with finding information relating to their own sexuality or to GLBT-related information for a patient. Students need access to information about the “coming out” process as well. Special resources are needed that point providers and students to other GLBT providers and students for general information sharing, socializing with peers, and referrals. Also mentioned was the need to have access to legal data about the personal rights of the GLBT professional, including employment discrimination, partner's rights in obtaining benefits, and other domestic life issues. Some commented that because not all medical librarians are comfortable with exploring GLBT topics, special reference services are needed.

One hundred and fifty respondents (79 of them GLBT persons) addressed the questions concerning how medical reference services can be changed so as to be perceived as GLBT-friendly and how access for this population can be enhanced. Advertising or displaying within the library the presence of special resources for the GLBT health professional and health consumer was indicated as one way to start. Having GLBT and pro-diversity pamphlets, signs, stickers, rainbow flags, or posters displayed as prominently as any other material and having showcases and exhibits on GLBT issues and events was also stressed. Displaying an equal access statement in addition to appropriate declarations on the library Web page expressing support of GLBT persons and a commitment to be sensitive to the needs of all persons may also be beneficial. Librarians should be open, nonjudgmental, accepting, caring, and willing to help. They may need to “win the trust” of the GLBT person. The use of nonsexist (gender-neutral) language, such as using the word “partner” instead of “spouse,” “husband,” or “wife” may be of benefit. Asking the patron if the information being sought is intended for a GLBT audience or patient was also proposed. “Much in the way schools can create a “gay-safe” space, so can reference services.”

Having a link on the library's Web page leading to resources for GLBT health care providers as well as consumers will be a message to all that being GLBT and seeking health information is welcome at that library. Easily found resources on sexuality and sexual and gender orientation would be particularly helpful to those patrons unable to directly ask a librarian for help. Posting useful Websites containing GLBT health information on commonly used medical and general librarian email discussion groups along with posing questions on these themes can increase awareness as well as inform people of good resources.

Reference services should respect the privacy and confidentially of the patron. One person felt that it might be a good idea to provide to medical librarians the option of referral to another, more comfortable, colleague if they are uncomfortable in dealing with GLBT topics. Hiring more “out” GLBT people to staff the reference department was recommended. Other recommendaions included creating an NLM fact sheet, finding aid, or subset in MEDLINE for GLBT topics and indexing the Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association in MEDLINE. Diversity training in professional schools might help the recently graduated health care provider and medical librarian to be comfortable in serving the needs of all peoples. Similar topics given as courses for continuing professional development may be appropriate for established practicing professionals.

No respondent reported having a negative experience with a medical librarian when requesting help on a GLBT topic. One patron was reported as being self-conscious and using hints and euphemisms, thus giving the reference interview a “furtive” atmosphere. There were also a few instances in which the patrons acted “horrified” that their patient had HIV infection, thus making for an uncomfortable reference interaction. There were many positive reference interactions reported by 50 persons, of which 21 were GLBT persons. The following were typical remarks:

“They treated my question like any other and were very helpful.”

“The person went beyond the scope of routine duties to assist with informational resources.”

“All of the librarians have been professional and there was no perceived discrimination.”

“Our reference librarian is awesome and has no trouble with any search on any topic no matter how different or potentially controversial.”

Perhaps the following sentence summarizes most of the responses in this section: “I have never experienced anything but friendly, helpful, and unbiased service at our medical library.” Medical librarians were happy to be able to make patrons feel comfortable when asking their questions. Many patrons were thankful for respectful, confidential, nonjudgmental assistance. Teenagers were very happy to get information about homosexuality from the librarian because they felt they could not ask parents or school counselors. One information specialist found that email reference help tended to make the interaction easier and more positive since the patron could question quite directly without being (or worrying about being) confronted with any judgmental looks or words from the librarian.

Some of the general comments illuminated the subject of this report. Stated one person: “I would rather go to a GLBT person in any department, if I had the opportunity, for the same reason (support in a typically conservative, heterosexual environment).” Another noted:

For those medical librarians in academic settings, I think it is very important to present a GLBT-friendly face to medical students and residents. This is the time when GLBT students are forming important opinions about the profession they are entering. Furthermore, and more importantly, it is the time when so many of our colleagues are forming or solidifying the ingrained biases and homophobia that have characterized and, in fact, plagued our profession. Open access to GLBT issues in a professional manner sends an important message—intolerance is no longer acceptable.

Finally:

Many health professionals may not be as “out” and comfortable in their own sexuality or gender identity to be advocates for their patients. Having a GLBT friendly reference librarian would increase the likelihood that they would be able to research issues that arise.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This survey is the first one reported on the information needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered health care professionals and their interactions with medical librarians. Although the survey sample is not a random one, the authors believe that the large sample size ensures credibility for the data, which they consider to be important and representative.

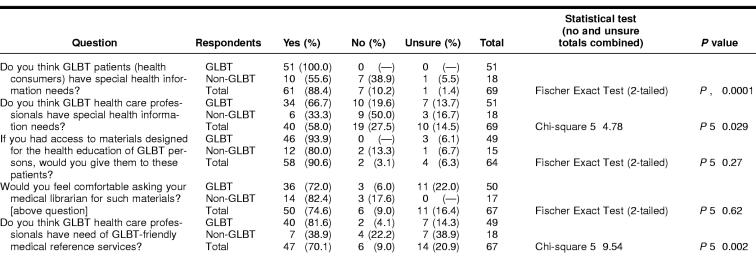

Most GLBT persons responded that they believed GLBT people have special information needs, as did the majority of non-GLBT participants, although there was a highly significant difference in the responses of these two groups among nonlibrarian health care professionals. This difference may be the result of unawareness on the part of non-GLBT persons or a belief that their needs are being met with traditional library services. Similar, though less statistically significant, results were obtained in answer to whether GLBT health care professionals also have special information needs. When asked if GLBT health professionals have need of GLBT-friendly reference services, a clear majority of respondents believed they did, although again with a highly significant difference in response between GLBT and non-GLBT nonlibrarian health care professionals, probably for the same reasons as given above.

There can be no question but that the GLBT population has unique information needs as demonstrated above and that the GLBT health provider needs and deserves to be assured of easy access to this information in order to provide quality care to all of his or her patients. Additionally, the clinician may need to procure information concerning the sometimes homophobic, hostile society (and even medical peer group) within which the professional must work [16, 17].

Less than half of medical librarians and students reported being approached for help with a topic where the concept of being GLBT was involved. Most of those who were approached considered these experiences positive, with only two medical librarians/students reporting having had a negative experience. About 20% of nonlibrarian health professionals and students reported positive experiences with medical librarians when seeking reference help with a GLBT topic, with no reports of negative experiences.

Approximately two-thirds of medical librarians and students felt that access to health information by GLBT persons “could/should be made easier.” GLBT and non-GLBT persons responded similarly to this question. When nonlibrarian health professionals were asked whether GLBT persons have special health information needs and whether GLBT health care professionals have need of GLBT-friendly medical reference services, there were highly significant differences in response rates between GLBT and non-GLBT persons, as shown in Table 3. It would appear that the majority of medical librarians participating in this survey were quite aware or attuned to the possibility of special needs in a GLBT patron. Many of the non-GLBT, nonlibrarian health care professionals surveyed, however, appear to be unaware or unsure of special needs in the GLBT population. Over 80% of GLBT nonlibrarian health professional participants perceive that they do in fact have special needs.

Table 3 Responses of non-librarian health professionals/students to yes/no/unsure questions

Medical librarians were almost universally “very comfortable” or “comfortable” with the possibility of being asked a reference question that includes GLBT subject matter. There was no statistically significant difference between GLBT and non-GLBT respondents, as show in Table 6.

GLBT and pro-diversity pamphlets, signs, stickers, rainbow flags, or posters in addition to showcases and exhibits on GLBT issues and events were noted as constructive ways to create a GLBT-friendly environment. Other useful ways to make the library more user friendly to GLBT patrons include having free bookmarks with GLBT related titles or special subject areas, distributing book and video lists of GLBT titles, arranging book jackets of recent acquisitions on bulletin boards, providing research guides or pathfinders that summarize the different types of GLBT information available, compiling a union list of GLBT-related books and periodical subscriptions, and publicizing the availability of GLBT-related materials in the library's newsletter or other printed media, such as local or regional GLBT newspapers [18].

Providing good GLBT resources that address the many previously presented information requirements of this group within the library, as well as supplying quality links on library Web pages, would clearly indicate to interested patrons that their needs are being recognized. One excellent example of a Web metapage,* compiled and maintained by Tom Fleming as part of the “Health Care Information Resources” site of McMaster University Health Sciences Library, located in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, is “Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Health Links.” Another page titled “Gay & Lesbian Health Care Practitioners Links”† is also filled with excellent resources. MEDLINEplus, a product of the National Library of Medicine, has a metapage “Gay/Lesbian Health”‡ with many interesting links to health resources specific to this group.

One frequently overlooked section of the GLBT population is middle-aged and older adults. Unfortunately, this segment of the aging population has not only remained invisible but also has to contend with persistent myths and stereotypes. As a result, many such persons encounter barriers to receiving proper medical and mental health care [19]. The librarian could provide access to information important to the aging GLBT population on topics such as depression and suicide, vision impairment, partner loss, visitation rights, and other issues of advancing years.

Perhaps the main reason that a GLBT health professional would prefer to approach a known GLBT librarian is the almost certain knowledge that the librarian would not display prejudice toward the health professional's particular sexuality or information requirement. Even without these positive displays of support, medical librarians, by providing friendly, caring, accepting, nonjudgmental, and confidential services, can do much to supply both the GLBT clinician and patient with appropriate reference resources. Librarians and libraries are uniquely individual and all of them must constantly assess and seek to improve their current methods of, approaches to, and marketing strategies for information delivery to all patrons.

There was a great disparity apparent in the highly significant difference in responses between GLBT and non-GLBT librarians in their awareness of the existence of the Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, as noted in Table 5. Subscribing to this journal might be an excellent start in the process of making one's library a GLBT-friendly place. Although the National Library of Medicine subscribes to this publication, it is not indexed in Index Medicus. Perhaps like other special groups medical journals such as Journal of the American Medical Women's Association and Journal of the National Medical Association, this journal will one day also be indexed so that appropriate citations will potentially be seen by PubMed searchers.

Table 5 Responses of medical librarians/students to yes/no questions

Understanding a patron's fear or unease about seeking reference assistance when seeking information might reveal his or her sexuality requires awareness and sensitivity on the part of the medical librarian, particularly when dealing with the needs of a medical student or resident. Working with such an individual demands certain skills that may not have been addressed in library school and may, in fact, be beyond the comfort level of the information professional. In such instances, it may be most prudent to honestly express lack of knowledge or discomfort with the topic and refer the patron to a colleague who would be more at ease. If no one is available, pointing out other sources of information, including another library, may be of great help to the patron. If this is not done, the patron will most assuredly sense the librarian's unease and may very well never again ask such a question of that librarian, or perhaps of any information professional.

It was quite inspiring to note that most encounters between clinicians and medical librarians were positive and productive. Almost all the information professionals expressed the desire to serve all patrons, regardless of which particular group(s) the patron might belong to. The vast majority were quite comfortable in being approached with a reference question that involved a GLBT concept. It is hoped that data gathered from the survey participants will serve to bring awareness to readers of this report and potentially help them to further enhance their efforts to serve the information needs of all patrons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the survey participants for taking the time to carefully answer the questions posed and for their trust.

Table 4 Responses of nonlibrarian health professionals/students to never/occasionally/often questions

APPENDIX

Survey of information needs of gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgendered health professionals

This survey is intended to find basic information about the interaction between the gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgendered (G/L/B/T) health care professional and the medical librarian. Some information about health information needs of G/L/B/T health consumers will also be investigated. To save space, the phrase “Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgendered” will be abbreviated as: G/L/B/T.

Anonymity of all participants will be respected. Names and e-mails will not be disclosed or published. With permission, the author may contact a participant by e-mail to clarify answers. Questionnaires will be deleted after the research report is written and published.

Name (not required):

E-mail (not required, but may be helpful):

If you typed your e-mail above, please re-enter e-mail as a check.

Are you willing to allow the author to contact you for clarification of answers if necessary?

Are you a Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgendered (G/L/B/T) person?

Are you a health care professional or student (non-medical librarian)?

Are you a medical librarian or library science student?

What is your age?

-

In what country do you reside?

Questions 10–28 are for health care professionals or students only. If you are a medical librarian or library science student, please go to the bottom of this page and click on “Next” to get to the next question area, beginning with question #28.

When in need of information for the benefit of a PATIENT'S care for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials, would you approach a medical librarian for help?: Never Occasionally Often

When in need of information for the benefit of a PATIENT'S care for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials AND for which the concept of being Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgendered (G/L/B/T) must be included in the search for information, would you approach a medical librarian for help?: Never Occasionally Often

If you are in need of information for RESEARCH purposes or for PERSONAL HEALTH purposes for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials and where the concepts of being G/L/B/T must be included in the search, would you approach a medical librarian for help?: Never Occasionally Often

If you knew that the medical librarian was G/L/B/T and you had need of information for the benefit of a PATIENT'S care for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials and for which the concept of being G/L/B/T must be included in the search for information, would you approach THIS medical librarian for help?: Never Occasionally Often

If you knew that the medical librarian was G/L/B/T and you had need of information for RESEARCH purposes or PERSONAL HEALTH purposes for which you have some difficulty in finding the necessary materials and for which the concept of being G/L/B/T must be included in the search for information, would you approach THIS medical librarian for help?: Never Occasionally Often

Do you think G/L/B/T PATIENTS (health consumers) have special health information needs?: Yes No Unsure

If you answered Yes to the above question, can you explain why?

Do you think G/L/B/T HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS have special information needs?: Yes No Unsure

If you answered Yes to the above question, can you explain why?

Do you provide patients who are G/L/B/T educational materials specifically designed for that population?: Yes No

If you had access to materials designed for the health education of G/L/B/T persons, would you give them to these patients?: Yes No Unsure

Would you feel comfortable asking your medical librarian for such materials?: Yes No Unsure

Do you think G/L/B/T health care professionals have need of G/L/B/T-friendly medical reference services?: Yes No Unsure

In what way(s) can medical reference services be changed so as to be perceived as G/L/B/T-friendly?

Have you ever had a negative experience with a medical librarian where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Yes No

If the answer to the above question was Yes, please explain:

Have you ever had a positive experience with a medical librarian where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Yes No

If the answer to the above question was Yes, please explain:

-

Finally, do you have any comments about this survey or about the information needs of Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgendered health care professionals and their interactions with the medical librarian?

This is the last question for health care professionals or students! Thank you. Please skip the questions in the next section and go directly to the bottom of that section to submit your responses. Questions 29–45 are for medical librarians or library science students only. Nonlibrarian health care professionals and students should only answer the questions presented in the previous section.

Have you been approached by HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS for help in finding information where the concept of being Gay/Lesbian/Bisexual/Transgendered (G/L/B/T) was part of the reference question?: Yes No

Have you been approached by PATIENTS (health consumers) for help in finding information where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Yes No

How comfortable are you (or would you be) if approached by a person seeking reference help where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Very Comfortable, Comfortable, Uncomfortable, Very Uncomfortable

Do you have any access to any special sources of health information for the G/L/B/T community or G/L/B/T health care professionals?: Yes No

Do you know of the existence of the Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association? Yes No

Do you feel that anything should/could be done to make access to health information for G/L/B/T health consumers or health care professionals easier?: Yes No

If you answered Yes to the above question, could you please explain in what way access to services could be enhanced?

Do you think G/L/B/T persons have special health information needs? Yes No

Can you explain why (or why not) G/L/B/T persons have special health information needs?

Do you think G/L/B/T health care professionals have need of G/L/B/T-friendly medical reference services?: Yes No

Can you explain why (or why not) G/L/B/T health care professionals have need of G/L/B/T-friendly medical reference services?

In what way(s) can medical reference services be changed so as to be perceived as G/L/B/T-friendly?

Have you ever had a negative experience with a patron where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Yes No

If the answer to the above question is Yes, can you please explain?

Have you ever had a positive experience with a patron where the concept of being G/L/B/T was part of the reference question?: Yes No

If the answer to the above question is Yes, can you please explain?

Finally, do you have any comments about this survey or about the information needs of G/L/B/T health care professionals and the interactions with the medical librarian?

Footnotes

* The Health Care Information Resources Website may be viewed at http://hsl.mcmaster.ca/tomflem/gay.html.

† The Gay & Lesbian Health Care Practitioners Links Website may be viewed at http://hsl/mcmaster.ca/tomflem/glbpract.html.

‡ The Gay/Lesbian Health Website may be viewed at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/gaylesbianhealth.html.

Contributor Information

Charles R. Fikar, Email: cfikar@svcmcny.org.

Latrina Keith, Email: lkeith@nyam.org.

REFERENCES

- Gough C, Greenblatt E. eds. Gay and lesbian library service. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Perry G. Health information for lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgendered people on the internet: context and content. Internet Ref Serv Q 2001;6(2):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Perry G. Health information for gay men on the internet. Health Care Internet 2002;6(1/2):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming T, Sullivant J. Consumer health materials for lesbians, gay men, bisexual and transgendered people. Public Libr Q 2000;18(3/4):95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gough C, Greenblatt E. eds. Gay and lesbian library service. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990:xxi–xxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce SL. Lesbian, gay and bisexual library service: a review of the literature. Public Libr. 2000 Sep–Oct. 39(5):270–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bott CJ. Fighting the silence: how to support your gay and straight students. Voice Youth Advocates. 2000 Apr. 23(1):22,24,26. [Google Scholar]

- Silence. In: The Macmillan Dictionary of Quotations. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books, 2000:532–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, Sell RL, Sember R, Silenzio VMB, Bowen DJ, Bradford J, Rothblum E, White J, Dunn P, Lawrence A, Wolfe D, and Xavier J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: findings and concerns. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2000 Oct. 4(3):101–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gay and Lesbian Medical Association and LGBT Health Experts. Healthy people 2010 companion document for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health. San Francisco, CA: Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JM. Health problems of lesbian women. Nurs Clin North Am. 1999 Jun. 34(2):381–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungvarski PJ, Grossman AH. Health problems of gay and bisexual men. Nurs Clin North Am. 1999 Jun. 34(2):313–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt E. Homosexuality: the evolution of a concept in the Library of Congress Subject Headings. In: Gough, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990:75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Roedell RF. Affirmative gay material in a hospital library collection. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1976 Oct. 64(4):423. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Bradford J. Methodological issues in research with lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. In: Carmichael JV, ed. Daring to find our names: the search for lesbigay library history. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fikar CR. The gay pediatrician: a report. J Homosex 1992;23(3):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druzin P, Shrier I, Yacowar M, and Rossignol M. Discrimination against gay, lesbian and bisexual family physicians by patients. CMAJ. 1998 Mar 10. 158(5):593–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough C. Making the library more user-friendly for gay and lesbian patrons. In: Gough, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1990:109–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A, D'Augelli , and O'Connell T. Being lesbian, gay, bisexual, and 60 or older in North America. In: Kimmel D, Martin D, eds. Midlife and aging in gay America: proceedings of the SAGE Conference 2000. Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press, 2002:23–40. [Google Scholar]