Abstract

Some adolescent girls perinatally infected with HIV (PIH) engage in sexual behavior that poses risks to their own well-being and that of sexual partners. Interventions to promote condom use among girls PIH may be most effective if provided prior to first sexual intercourse. With in-depth interviews, we explored gender- and HIV-specific informational and motivational factors that might be important for sexual risk reduction interventions designed to reach U.S. girls PIH before they first engage in sexual intercourse. Open-ended interview questions and vignettes were employed. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model guided descriptive qualitative analyses. Participants (20 girls PIH ages 12–16 years) had experienced kissing (n = 12), genital touching (n = 6), and oral (n = 3), vaginal (n = 2), and anal sex (n = 1). Most knew sex poses transmission risks but not all knew anal sex is risky. Motivations for and against condom use included concerns about: sexual transmission, psychological barriers, and partners’ awareness of the girl’s HIV+ status. Girls were highly motivated to prevent transmission, but challenged by lack of condom negotiation skills as well as negative potential consequences of unsafe sex refusal and HIV status disclosure. Perhaps most critical for intervention development is the finding that some girls believe disclosing one’s HIV status to a male partner shifts the responsibility of preventing transmission to that partner. These results suggest a modified IMB model that highlights the role of disclosure in affecting condom use among girls PIH and their partners. Implications for cognitive-behavioral interventions are discussed.

Keywords: adolescents, HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS prevention, youth, sexual health

In 2006, roughly 5,000 U.S. children and youth living with HIV had acquired HIV perinatally (Gavin et al., 2009). Once not expected to reach age five, most U.S. youth perinatally-infected with HIV (PIH) have endured years of antiretroviral treatment (Wood, Shah, Steenhoff, & Rutstein, 2009). Most know their HIV status by age 12 (Butler, Williams, Howland, Storm, Hutton, Seage, & the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 219C Study Team), and enter adolescence knowing through sex they could: a) transmit HIV to sexual partners and offspring (Ezeanolue, Wodi, Patel, Dieudonne, & Oleske, 2006); b) become re-infected with another HIV strain (Smith, Richman, & Little, 2005); and c) contract a sexually transmitted infection (STI) that threatens their health (Buchacz et al., 2004). Often, their HIV status remains unknown to many friends and family (Lam, Naar-King, and Wright, 2007), as risks of disclosing are perceived as substantial at a time when social acceptance is critical. Thus, youth PIH are challenged with balancing sexual exploration against concerns about protecting themselves from re-infection and other STIs, protecting others from HIV transmission, and preserving or enhancing social acceptance.

Consistent with normal adolescent development, some U.S. youth PIH are having sex—defined here as oral, vaginal, or anal intercourse (Bauermeister, Elkington, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Mellins, 2009; Brogly et al., 2007; Ezeanolue et al., 2006; Koenig, Espinoza, Hodge, & Ruffo, 2007; Levine, Aaron, & Foster, 2006). Youth PIH (ages 9–16 years) may be less likely than HIV-uninfected peers to report any sexual behavior, but some are engaging in romantic and sexual behavior (Bauermeister, Elkington, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Mellins, 2009). Ideally, interventions promoting consistent condom use would be provided prior to first sex, because condom use at first sex is predictive of subsequent condom use (Miller, Levin, Whitaker, & Xu, 1998; Shafii, Stovel, & Holmes, 2007).

Some factors might affect condom use among both youth PIH and their HIV-negative peers. However, motivations and barriers specific to living with a chronic, highly-stigmatized, life-threatening STI likely exist. No known U.S. studies of youth PIH have examined motivations and barriers related to condom use, but Fernet and colleagues (2007) explored these topics among 29 Canadian youth PIH ages 10–18 years; six had experienced sex. Similar to studies of U.S. youth with non-perinatally-acquired HIV (Forsberg, Kind, Delaronde, Geary, & the Hemophilia Behavioral Evaluative Intervention Project Committee, 1996; Hosek, Harper, & Domanico, 2000), Canadian youth PIH were aware of HIV transmission risks and considered disclosing to partners, but feared rejection (Fernet et al., 2007). Studies are needed to identify modifiable, population-specific determinants of condom use to address with theoretically-based safer sex interventions for U.S. youth PIH prior to first sex.

Experiences of youths’ sexual development/behavior differ by gender. Girls struggle to balance sexual responsibility associated with traditional gender norms against sexual desires (Breakwell & Millward, 1997; Shoveller, Johnson, Langile, & Mitchell, 2004). If concerned about HIV and STIs, girls tend to delay vaginal sex, whereas boys tend to practice harm-reduction along with vaginal sex (Michels, Kropp, Eyre, & Halpern-Felsher, 2005). Moreover, girls are at-risk for gender-based violence and sexual power imbalances (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). These gendered factors likely affect the sexual experiences of youth PIH and might necessitate gender-specific interventions.

The Present Study

We sought to determine factors that may affect condom use among girls PIH (ages 12–16 years) and could serve as appropriate foci for safer sex interventions aimed at girls PIH prior to their first sex. Interviews with girls these ages are ideal for capturing beliefs and attitudes about condom use, because by age 12 most girls PIH know their status and by age 16 some have had sex (Bauermeister et al., 2009).

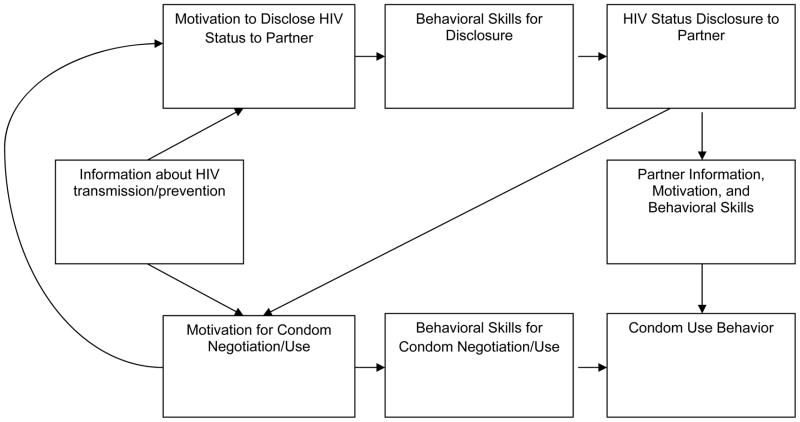

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model (Fisher & Fisher, 1992) guided analysis. The IMB model suggests implementation of condom-related behavioral skills is more likely when people have the necessary information and motivation. Elicitation research is considered essential for determining appropriate IMB model foci for interventions (Fisher & Fisher, 1992). Behavioral skills were not assessed in the present study because: a) behavioral skills required for safer sex (i.e., for condom acquisition, negotiation, and application) are well-established (Fisher & Fisher, 1992); and b) the importance of addressing these skills in risk reduction interventions is clear (Crepaz at al., 2009; Lyles et al., 2007).

Methods

A mixed methods study was conducted with 20 girls PIH. Eligible girls were PIH, ages 12–16 years, aware of their HIV status, attending select pediatric HIV clinics in New York, New York, U.S., and without a documented IQ < 70. Girls were recruited from: a) an ongoing quantitative psycho-social and behavioral study of youth PIH (Bauermeister et al., 2009); and b) pediatric HIV clinics. Because the open-ended interview focused on heterosexual relationships, girls who were not interested in boys were informed some questions may not apply. In accordance with IRB approval, girls provided assent; parents/guardians provided consent. Girls and parents/guardians were told responses would not be shared with parents/guardians or clinic staff. When girls reported engaging in unprotected sex or sex without HIV status disclosure, study procedures dictated referral to their medical provider for sex education (only one participant required referral). Girls received $25.00 and transportation reimbursement.

Girls completed a sexual behavior interview developed for youth PIH (Bauermeister et al., 2009) via Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI; Ellen et al., 2002) and completed a 45–90 minute semi-structured qualitative interview with the primary author.i The interview guide was developed with a multidisciplinary research group (Pinto, McKay, & Escobar, 2008) to assess factors affecting girls’ sexual behavior with boys. The primary question was: “What is it like for you to grow up and deal with puberty, boys, sex and relationships?” Prompts included: “When you are thinking you might be romantic or sexual with a boy, what comes to mind?” and “How do you think you are different from your friends or other girls you know because you have HIV?” Vignettes were employed because the research involved sensitive topics many youth find difficult to discuss (Table 1; Barter & Renold, 2000); inquiry focused on motivation for the vignette character’s thoughts or behavior (i.e., “What would make her . . . ?”). To determine participants’ motivations, the interviewer asked: “In what ways are you similar to or different from her?”). In the open-ended interview, “sex” was never defined—girls were left to make their own interpretations.

Table 1.

Vignettes included in the semi-structured open-ended interview.

|

Notes: Responses to vignettes were followed with questions such as “in what ways are you like [vignette character] or different from her?” Also, with the exception of vignette G, vignettes did not specify whether or not the girls in the vignettes were living with HIV

Information about HIV transmission was assessed toward the end of the interview to avoid priming effects (Rasinski, Visser, Zagatsky, & Rickett, 2005). Girls were asked to list HIV transmission modes and to clarify what they meant by “sex,” (i.e., oral/vaginal/anal). Girls were also asked: “What do you do or could you do to keep from passing HIV to your partner during sex?”

Analysis and Interpretation

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed. Using NVivo 8, qualitative descriptive coding was employed (Sandelowski, 2000). Three authors with diverse ethnic backgrounds independently read texts, identified main themes, and developed a codebook. Two authors coded all texts, compared coding, then designated final codes. Concordance with final codes was high (average was > 75%) [calculation= times coded correctly/ (total times should have been coded + commissions + omissions)]. Relevant themes were fit within existing IMB model constructs and the IMB model was then adapted to fit outstanding themes.

Results

Twenty girls PIH ages 12 to 16 (mode = 14) years participated (Table 2). The majority self-identified as a racial/ethnic minority and straight/heterosexual. Most lived in poor urban areas, mirroring the population affected in New York City (HIV Epidemiology Program, 2007). Few girls reported experience with oral, vaginal or anal sex; these reports were consistent between quantitative (ACASI) and qualitative (open-ended interview) assessments. No girls reported ever having a known HIV-positive sexual partner.

Table 2.

Characteristics of girls (n= 20, ages 12–16 years) living with perinatally acquired HIV

| Participants n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Biracial | 1 (5%) |

| Black/African American | 7 (35%) |

| Black Latina | 5 (25%) |

| Caribbean | 1 (5%) |

| White Latina | 6 (30%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Straight/heterosexual | 15 (75%) |

| Bisexual | 3 (15%) |

| Other/unsure | 2 (10%) |

| Sexual Experience | |

| Had a boyfriend | 16 (80%) |

| Kissed Romantically | 12 (60%) |

| Genitals had been touched by a boy | 6 (30%) |

| Touched a boy’s genitals | 3 (15%) |

| Engaged in any type of sexual intercourse (oral, vaginal, or anal) | 3 (15%) |

| Oral sex | 3 (15%) |

| Vaginal sex | 2 (10%) |

| Anal sex | 1 (5%) |

| HIV Transmission Knowledge | |

| Knew oral sex is a transmission risk | 11 (55%) |

| Knew vaginal sex is a transmission risk | 18 (90%) |

| Knew anal sex is a transmission risk | 9 (45%) |

Information regarding transmission

Most girls possessed accurate HIV transmission knowledge; 19 knew HIV could be transmitted through sex (Table 2). All who suggested vaginal sex posed transmission risks (n=18) knew condoms could prevent transmission. Fewer girls thought oral and anal sex posed HIV transmission risks. None reported that strategies other than condom use and abstinence could prevent sexual transmission of HIV.

Motivating Factors Regarding Safer Sexual Behavior

As with HIV-negative girls (Widdice, Cornell, Liang, & Halpern-Felsher, 2006), condom use motivations for girls PIH included desire to prevent pregnancy and STIs. Additionally, three HIV-specific motivation themes emerged: a) concerns about transmitting HIV to sexual partners; b) emotional/psychological barriers to condom use; and c) HIV status disclosure to partners.

Concerns about Transmitting HIV to Sexual Partners

Girls seriously regarded the potential for transmitting HIV to sexual partners, as stated by a 14 year-old girl who reported risky sex: “I feel like I’m carrying a weapon around with me…a sexually weapon, and … I wouldn’t want nobody to do it to me [pass HIV] so I wouldn’t do it to them purposely.” Concerns about transmission led other girls to avoid or delay sex indefinitely, as a 15 year-old girl described: “You don’t want to give it to anybody else because you don’t want anybody else to go through what you’re going through, so you think you’re going to be a virgin for the rest of your life.”

Girls with some sexual experience talked about the importance of using condoms—to prevent their “weapon” from causing harm. Often condom use was declared a precondition for sex, and more important than avoiding rejection. One 15-year-old girl who had kissed but had never had sex said: “I don’t think I could have unprotected sex. I’m scared that I might get pregnant or pass HIV to somebody. I’d rather lose the person than to have both of those things happen to me.” Some sexually inexperienced girls were confident they could refuse unsafe sex. Although such confidence might be naïve, one 15 year-old girl who had five lifetime vaginal sex partners and reported 100% condom use for vaginal sex suggested: “I don’t want to be blamed for anything so that’s why I tell them use a condom or nothing [no sex].”

Emotional/Psychological Barriers to Condom Use

Despite concerns about HIV transmission, girls identified multiple emotional/psychological barriers to condom use. Despite anger, no girls reported desire to transmit HIV to others. However, anger could lead some girls to risky sex. A 16 year-old girl who had kissed and touched stated: “I have to make sure I wear [my partner wears] a condom. So, yeah, I do feel like it’s different [than for HIV-negative girls].” When asked how she felt about that, she replied: “Mad. Because—but at some times I want to do it how everybody else do it. So it makes me angry. It’s like I can’t have fun because I have to think about that.”

Some girls revealed internal conflicts that might impact risk-taking. Consistent with HIV-negative girls (O’Sullivan, Cheng, Harris, & Brooks-Gunn, 2007), girls PIH want to be accepted, loved, and wanted. Girls want to avoid transmission as well as fear, interpersonal conflict, and rejection that could result from asking a partner to wear a condom. When asked “why some people won’t ask a guy to wear a condom,” a 14-year-old girl who had kissed, touched and talked about not wanting to transmit HIV to partners replied : “They’re scared to ask a guy to wear a condom . . . . because the guy might say no.” Other girls PIH might avoid condom negotiation due to lack of skills or fear the guy will suspect they have HIV or other STIs. After hearing about a girl who won’t ask a guy to wear a condom, one 14 year-old girl with no experience kissing, touching, or having sex said: “He’ll probably confront her why—why she wants him to wear a condom. And then she probably don’t want to tell him why.”

Emotional/psychological barriers combined with few condom negotiation skills can have unfortunate consequences. The 14-year-old girl who described “carrying a weapon” had unprotected vaginal and anal sex with her partner after he infected her with syphilis and herpes. Her desire for love, fear of abandonment, lack of skills and low self-confidence outweighed her motivation to prevention transmission: “like when I have sex without a condom, I—every time I almost have sex with him without a condom—I would think about that [feeling bad about possible transmission].”ii

HIV Status Disclosure

Sometimes disclosure was considered an important precursor to sex and an impetus for safer sex. Moreover, disclosure was seen as a way of absolving oneself of guilt and blame associated with transmission risks. Some girls thought disclosure would lead partners to use condoms, like one 15 year-old girl who had kissed, and thought that after disclosure: “[we’ll] probably be safer . . . him using condoms and stuff like that, and for sex.”

For some, disclosure was viewed as a means of shifting responsibility for condom use to the partner. When asked “Whose responsibility is it for condoms?” in response to vignette F (Table 1), a 14 year-old girl with no experience kissing, touching, or having sex said: “. . . if she has HIV and he doesn’t know, then it’s her responsibility.” She suggested responsibility shifts following disclosure: “If she already told the person that she’s with that she has HIV and he says that he doesn’t care and he didn’t put on a condom, then it’s his fault . . . .”

A Modified IMB Model for Condom Use among Girls PIH

Findings suggest condom use among girls PIH is more complex than for HIV-negative girls. Not every girl PIH will disclose to each partner, and non-disclosure might simplify condom use dynamics, especially when girls are highly motivated to use condoms. However, when girls PIH do disclose, their sexual partners might be granted a greater role in condom use decision-making. The resulting dyadic IMB model for girls PIH illustrates the potential importance of sexual partners’ information, motivation and behavioral skills as well as disclosure in determining condom use (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modified Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model for Condom Use among Adolescent Girls with Perinatally-Acquired HIV

Discussion

This paper examined knowledge about HIV transmission and motivations for condom use among urban adolescent girls PIH (ages 12–16 years) to elicit critical information for intervention development. Consistent with Bauermeister et al., (2009), girls reported a range of sexual behavior, but only three had experienced oral, vaginal, or anal sex; roughly half of all participants were unaware of HIV transmission risks associated with anal sex and two did not identify vaginal sex as posing transmission risksii (Wiener, Battles, & Wood, 2007). These findings are important for developing behavioral interventions. Some HIV care providers might discuss condom use with girls PIH, but not inform them of specific sexual situations in which condom use is important (e.g.,,anal sex). Continuing education programs for care providers of girls PIH should provide skills for discussing transmission risks like anal sex.

Findings suggest girls PIH might feel like they are “carrying a weapon” that threatens their sexual partners. For these girls, HIV status disclosure to partners is a fundamental consideration. Girls expressed two functions of disclosure related to condom use: a) increasing condom use; and b) shifting responsibility for condom use to the partner. Among HIV-positive youth, disclosure has been associated with reporting less (D’Angelo, Abdalian, Sarr, Hoffman, & Belzer, 2001) and more condom use (Lee, Rotheram-Borus, & Hara, 1999; Sturdevant et al., 2001). A shift in perceptions of condom responsibility might explain why condom use does not always increase with disclosure (e.g., Lee, Rotheram-Borus, & Hara, 1999; Sturdevant et al., 2001). Following disclosure, a girl PIH might lack motivation for condom negotiation, as her sex partner knows about her “weapon” and can choose whether or not to protect himself from it.

The dyadic IMB model for girls PIH has potential for guiding interventions to reach girls before and after they engage in their formative sexual experiences. Research expanding the IMB model to dyads (Harman & Amico, 2009) has not considered unique dyadic issues among youth PIH and their HIV-negative partners—or among sero different adult dyads. The dyadic IMB model for girls PIH should be explored further among a larger sample of sexually-active girls PIH, to determine if these anticipated determinants of condom use reflect girls’ lived experiences as they mature sexually. Additionally, including partners of girls PIH, while difficult (Pappas-DeLuca, Kraft, Edwards, Casillas, Harvey, & Huszti, 2006), is critical to accurately understand condom use dynamics. Similarly, research among boys PIH could help identify gender differences in these partnered dynamics.

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Some responses might not reflect motivations specific to informants because vignettes were used to elicit motivating factors. However, focusing on hypothetical characters could have increased girls’ comfort in honestly discussing sensitive topics. Girls were not asked specifically about HIV status disclosure or behavioral skills, so related information was not available for all participants. This analysis focused on preventing risky sex among girls PIH without fully understanding important positive aspects of their sexual development. To protect participants’ confidentiality, data were anonymized; thus, data cannot be linked with the larger study from which some participants were recruited, and we cannot measure changes longitudinally. Finally, about half of girls in this study were co-enrolled in another study; they could be over-studied and may differ in some ways from other girls PIH. Despite these limitations, this study marks an important step toward developing evidence-based and theoretically-driven safer sex promotion interventions aimed at girls PIH who have not yet had sex.

These findings provide a preliminary model for understanding sexual risk among girls PIH and indicate key foci for interventions. Like programs for HIV-negative youth (DiClemente et al., 2008), interventions for girls PIH should build on motivations to prevent pregnancy and STIs, and enhance behavioral skills for condom negotiation. Interventions should also address specific challenges girls face developing sexually while living with a chronic, life-threatening, highly stigmatized STI. Successful interventions for girls PIH might: a) increase HIV transmission knowledge, especially regarding anal sex; b) build on their desire to prevent HIV transmission; c) address emotional barriers to condom use; and d) counter girls’ beliefs about shifting condom responsibility to partners following HIV status disclosure.

Acknowledgments

During data collection, Dr. Marhefka was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NRSA T32 MH19139, Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D., Program Director) and Drs. Marhefka and Mellins were supported by the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (P30 MH43520; Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D., Principal Investigator), which provided funding for this study. Some data were collected in conjunction with a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH069133, Mental Health and Risk in HIV+ Youth and Seroreverters; Claude Ann Mellins, Ph.D., Principal Investigator.

Footnotes

Of note, three of the participants knew the interviewer from prior participation in a behavioral intervention study with youth PIH and their families—in all other cases there was no prior relationship between interviewer and interviewee.

It was not standard protocol to inform girls of misconceptions; however, the girl who had engaged in anal sex and did not know it was a transmission risk was informed of the risk following the interview.

Contributor Information

Stephanie L. Marhefka, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA

Cidna R. Valentin, City University of New York, New York, New York, USA

Rogério M. Pinto, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA

Nicole Demetriou, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, USA.

Andrew Wiznia, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA.

Claude Ann Mellins, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA.

References

- Barter C, Renold E. ‘I wanna tell you a story’: Exploring the application of vignettes in qualitative research with children and young people. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2000;3:307–323. doi: 10.1080/13645570050178594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Elkington K, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Sexual behavior and perceived peer norms: Comparing perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-affected youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1110–1122. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9315-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell GW, Millward LJ. Sexual self-concept and sexual risk-taking. Journal of Adolescence. 1997;20:29–41. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0062. 10.1006.jado.1996.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogly SB, Watts DH, Ylitalo N, Franco EL, Seage GR, III, Oleske J, Van Dyke R. Reproductive health of adolescent girls perinatally infected with HIV. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1047–1052. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, Kerndt PR, Byers RH, Holmberg SD, Klausner JD. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. AIDS. 2004;18:2075. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AM, Williams PL, Howland LC, Storm D, Hutton N, Seage GR, III the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 219C Study Team. Impact of disclosure on health-related quality of life among children and adolescents living with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2009;123:935–943. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay Ls, O’Leary A. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African American females in the United States: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo LJ, Abdalian SE, Sarr M, Hoffman N, Belzer M. Disclosure of serostatus by HIV infected youth: The experience of the REACH study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(Supplement 1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Crittenden CP, Rose E, Sales JM, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Salazar LF. Psychosocial predictors of HIV-associated sexual behaviors and the efficacy of prevention interventions in adolescents at-risk for HIV infection: What works and what doesn’t work? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:598–605. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181775edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen JM, Gurvey JE, Pasch L, Tschann J, Nanda JP, Catania J. A randomized comparison of A-CASI and phone interviews to assess STD/HIV-related risk behaviors in teens. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:26–30. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeanolue EE, Wodi AP, Patel R, Dieudonne A, Oleske JM. Sexual behaviors and procreational intentions of adolescents and young adults with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection: Experience of an urban tertiary center. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernet M, Proulx-Boucher K, Richard M, Levy JJ, Otis J, Samson J, Trottier G. Issues of sexuality and prevention among adolescents living with HIV/AIDS since birth. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2007;16:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg AD, King G, Delaronde SR, Geary MK the Hemophilia Behavioral Evaluative Intervention Project Committee. Maintaining safer sex behaviours in HIV-infected adolescents with haemophilia. AIDS Care. 1996;8:629–640. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin L, MacKay AP, Brown K, Harrier S, Ventura SJ, Kann L, Ryan G. Sexual and reproductive health of persons aged 10–24 years--- United States, 2002–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2009;58:1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman JJ, Amico KR. The relationship-oriented information-motivation-behavioral skills model: A multilevel structural equation model among dyads. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13:173–184. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV Epidemiology Program. Pediatric & Adolescent HIV/AIDS Surveillance Update, New York City. 2007 Retrieved December 5, 2008, from http://home2.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/dires-pedhiv-report-2007.pdf.

- Hosek SG, Harper GW, Domanico R. Psychosocial and social difficulties of adolescents living with HIV: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 2000;25:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LJ, Espinoza L, Hodge K, Ruffo N. Young, seropositive, and pregnant: Epidemiologic and psychosocial perspectives on pregnant adolescents with human immunodeficiency virus infection. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(Supplement 1):S123–S131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PK, Naar-King S, Wright K. Social support and disclosure as predictors of mental health in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2007;21:20–29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Hara P. Disclosure of serostatus among youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:33–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1025415418759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AB, Aaron E, Foster J. Pregnancy in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:765–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, Mullins MM. Best-evidence interventions: Findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:133–143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels TM, Kropp RY, Eyre SL, Halpern-Felsher BL. Initiating sexual experiences: How do young adolescents make decisions regarding early sexual activity? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:583–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00112.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, Xu X. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: The impact of mother-adolescent communication. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1542–1544. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Cheng MM, Harris KM, Brooks-Gunn J. I wanna hold your hand: The progression of social, romantic and sexual events in adolescent relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39:100–107. doi: 10.1363/3910007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas-DeLuca KA, Kraft JM, Edwards SL, Casillas A, Harvey SM, Hustzi HC. Recruiting and retaining couples for an HIV prevention intervention: Lessons learned from the PARTNERS project. Health Education Research. 2006;21:611–620. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM, McKay MM, Escobar C. “You’ve gotta know the community”: Minority women make recommendations about community-focused health research. Women’s Health. 2008;47:83–104. doi: 10.1300/J013v47n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasinski KA, Visser PS, Zagatsky M, Rickett EM. Using implicit goal priming to improve the quality of self-report data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2005;41:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods- Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafii R, Stovel K, Holmes K. Association between condom use at sexual debut and subsequent sexual trajectories: A longitudinal study using biomarkers. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1090–1096. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoveller JA, Johnson JL, Langile DB, Mitchell T. Socio-cultural influences on young people’s sexual development. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59:473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Richman DD, Little SJ. HIV superinfection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;192:438–444. doi: 10.1086/431682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturdevant MS, Belzer M, Weissman G, Riedman LB, Sarr M, Muenz LR. The relationship of unsafe sexual behavior and the characteristics of sexual partners of HIV infected and HIV uninfected adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(Supplement 1):64–71. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0074–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdice LE, Cornell JL, Liang W, Halpern-Felsher BL. Having sex and condom use: Potential risks and benefits reported by young, sexually inexperienced adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:588–595. doi: 10.1177/1557988307300784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Battles H, Wood L. A longitudinal study of adolescents with perinatally or transfusion acquired HIV infection: Sexual knowledge, risk reduction self-efficacy and sexual behavior. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:471–478. doi: 10.1177/1545109709341082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, Rutstein RM. The impact of AIDS diagnoses on long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric outcomes of surviving adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS. 2009;23:1859–1865. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]