Abstract

Juniperus excelsa M.B subsp. Polycarpos (K.Koch), collected from south of Iran, was subjected to hydrodistillation using clevenger apparatus to obtain essential oil. The essential was analyzed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) and studied for antimicrobial, antifungal and antioxidant activities. The results indicated α-pinene (67.71%) as the major compound and α-cedral (11.5%), δ3-carene (5.19%) and limonene (4.41%) in moderate amounts. Antimicrobial tests were carried out using disk diffusion method, followed by the measurement of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). All the Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria were susceptible to essential oil. The oil showed radical scavenging and antioxidant effects.

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, antioxidant activity, essential oil, Juniperus excelsa, thin layer chromatography autographic assay

INTRODUCTION

Free radicals are produced during cell metabolism in normal and pathologic conditions, which lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS have an important role in the onset of some diseases such as coronary heart disease, neurodegenaration (Parkinson's diseases), asthma, arthritis, cancer and cirrhosis.[1–3] Antioxidants can control the destruction of biomolecules caused by free radicals.[2,3] Butylated hydroxyltoulene (BHT) and butylated hydroxylanisole (BHA) are two major synthetic antioxidants, with a wide range of usage in food industries. Because of the side effects of artificial antioxidants, replacement of them with natural antioxidants is highly considered.[4] Essential oils are one of the natural sources of antioxidants with a great potential for application in nutraceutical and pharmaceutical products. Phenolic compounds present in essential oils such as thymol, carvacrol and eugenol are responsible for radical scavenging and prevention of lipid peroxidation as well as antimicrobial properties, respectively.[5,6]

Juniperus is one of the major genera of Cupressaceae family. It is estimated that 70 species of Juniperus are distributed throughout the world.[7] Juniperus is represented in Iran by five species. Juniperus excelsa is divided to two subspecies including J. excelsa M. B subsp. excelsa and J. excelsa M. B subsp. Polycarpos (K. Koch) Takhtajan.[8,9] Juniperus species are used for the treatment of hyperglycemia, tuberculosis, bronchitis, pneumonia, ulcers, intestinal worms, to heal wounds and cure liver diseases.[10,11] The boiled leaves or fruits with animal fixed oil of J. excelsa M. B subsp. Polycarpos are used for the treatment of earache in Hormozgan province, south of Iran.[12]

The purpose of this work is to test the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oils of J. excelsa M. B subsp. Polycarpos for, evaluation as food preservative.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials

Leaves of J. excelsa M. B subsp. Polycarpos were collected from Genu mountain, North of Persian Gulf, Hormozgan Province, Iran. The plant was identified by Mr. M. Soltanipour (Natural Resource and Animal Assar Research Center of Hormozgan, Iran). A voucher specimen (Herbarium No. 323) was deposited at Herbarium of School of Pharmacy, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

Extraction of essential oil

Air-dried plant materials (200 g) were submitted to hydrodistillation using clevenger apparatus to obtain 0.5% essential oil. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analyses were carried out using a Hewlett-Packard gas chromatograph HP-6890 with mass-selective detector HP-5973, USA. The gas chromatograph was equipped with a HP-5MS capillary column (phenylmethylsiloxane, 25 m × 0.25 mm i.d.). The oven temperature was programmed from 60°C (4 minutes) to 250°C at a rate of 3°C/minute and finally 10 minutes at 250°C. The carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 1.2 ml/minute. The mass spectrometer was operating in the electron ionization mode at 70 eV. The interface temperature was 250°C and the mass range was 30–600 m/z. Identification of components was based on a comparison of their retention indices (RIs) and mass spectra with Wiley (275) and Adams’ libraries spectra.[13]

Antimicrobial screening

Screening of the antimicrobials was investigated on Gram positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus PTCC 1112, Staphylococcus epidermidis PTCC 1114, Bacillus subtilis PTCC 1023, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 8043), Gram negative bacteria (Escherchia coli PTCC 1338, Shigella sonnei PTCC 1235, Proteus vulgaris PTCC 1312, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PTCC 1047, Salmonella typhi PTCC1609), yeasts (Candida albicans ATCC 14053, Candida kefyr ATCC 3826) and fungi (Aspergillus niger PLM 1140, Aspergillus fumigatus PLM 712). Disk diffusion method was employed for the determination of antimicrobial activity of the essential oil. Briefly, a suspension of the tested microorganism that contained 1.5 × 108 colony-forming unit/ml was prepared and then spread on a solid medium (nutrient agar) by a swab. Paper disks were impregnated with different amounts of the oil and placed on inoculated plates and left for 15 minutes at room temperature. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours for bacteria and at 27°C for 48 hours for the yeasts and fungi. The diameters of inhibition zones were measured in millimeters. Amphotericine-B, Ampicillin and Gentamicin were used as positive controls for microorganisms.[14]

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration

A microdilution broth susceptibility assay was used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the essential oil. To do this, 2 ml of a microbial suspension containing 5 × 105 CFU/ml of nutrient broth was prepared. Then, according to the serial dilution, different amounts of the essential oil were added to each tube. One of the tubes contained no essential oil and it was kept as positive control and the other one which contained no microorganism, as a negative one. After incubation for 24 hours for bacteria at 37°C, the first tube without turbidity was determined as the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC).[14]

Reduction of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical and β-carotene bleaching test

Autography was performed with slight modification. Essential oil was diluted with n-hexane (1:10) and applied on thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (5 μl) and the TLC was developed with toluene:ethyl acetate (93:7) as the mobile phase. After drying the plate, it was sprayed with 100 mM DPPH solution in methanol. The plate was examined for 30 minutes after spraying. Active compounds were visualized as yellow spots against a purple background.[10,15]

The TLC developed by the above mentioned solvent system was sprayed with β-carotene in CHCl3(9 mg/30 ml) including two drops of linoleic acid. The plate was kept under sunlight for 30 minutes. Active compound was visualized as yellow spot against bleached background. Active compounds were detected by spraying anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid reagent on another TLC plate.[10,16]

Determination of antioxidant activity using DPPH

The antioxidant activities of essential oil and the standard antioxidant were assessed on the basis of radical scavenging effect of the stable DPPH free radical. Exactly 200 μl of a 100 mM solution of DPPH radical in methanol was mixed with 20 μl of oil (or standard antioxidants). The concentrations of oil were 12.5-400 μg/ml. After mixing, it was left for 30 minutes at room temperature. The DPPH radical inhibition was measured at 490 nm by using a microplate reader.[17]

The EC50 of each sample (concentration in μg/ml required to inhibit DPPH radical formation by 50%) was calculated. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

The antioxidant activity (AOA) was given by:

100 - [(A) sample - (A) blank × 100/(A) control],

where "A" is the absorbance of the color formed in microplates wells. DPPH was used as control (without plant extract) and the blank contains methanol. All the tests were performed in triplicate.[17] The EC50 value was calculated by non-linear curve-fitting and was presented by their respective 95% confidence limit using Graph Pad Prism 3.02.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

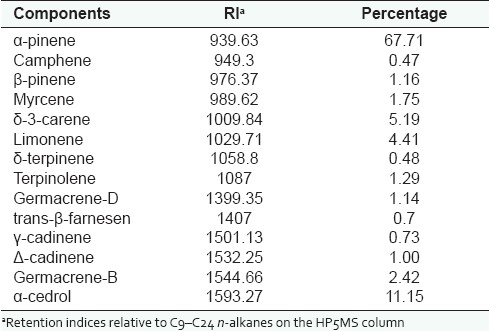

The percentage of essential oil was 0.5%. Table 1 lists the chemical components of the oil. Major compound was found to be α-pinene (67.71%), whereas α-cedrol (11.5%), δ3-carene (5.19%) and limonene (4.41%) were present in moderate amounts.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of essential oil of J. excelsa

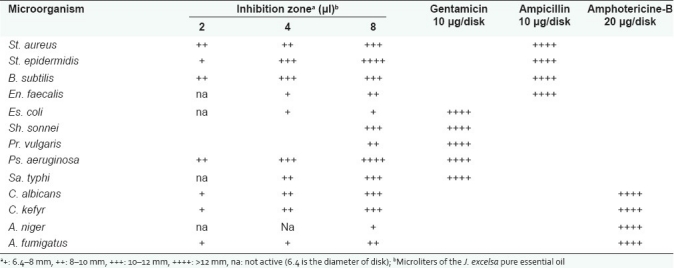

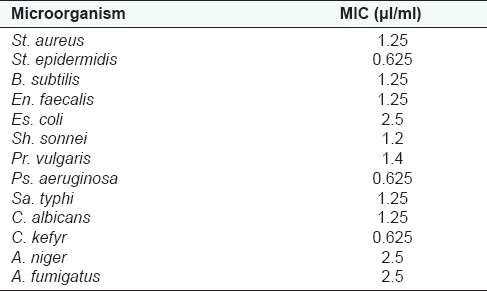

The in vitro antimicrobial tests of the essential oil of J. excelsa resulted in a range of growth inhibition pattern against pathogenic microorganisms. The results were obtained using disk diffusion method, followed by the measurement of MIC for essential oil. According to the disk diffusion method results, all of the microorganisms were inhibited by the amount of 8 μl/disk of pure essential oil [Table 1]. From Table 2 it can be observed that all the Gram positive and negative bacteria tested were susceptible to the action of J. excelsa essential oil, with a range of MIC values from 0.625 to 2.5 μl/ml. In general, susceptibility of Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria to the essential oil of J. excelsa has no significant difference. The most sensitive bacteria against the essential oil were St. epidermidis and Ps. aeruginosa.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of J. excelsa essential oil

Investigations on the antimicrobial activity of several Juniperus essential oils have been carried out previously. Three samples of Juniper (J. communis) oil berry and selected enantiomers including (+) α-pinene, (−) α-pinene, (−) β-pinene and p-cymene have been tested against fungi and bacteria. One sample of the essential oils showed the strongest antimicrobial activity. It was found that majority of (−) α-pinene contributed for creation of this effect. However, crude essential oil was much more effective than the selected enantiomers.[18]

Antioxidant and radical scavenging capacities of essential oil were assessed by TLC autographic assay with β-carotene and DPPH radical, respectively. One compound inhibited the lipid peroxidation (Rf = 0.407) while six compounds reduced the DPPH radicals (0.033, 0407, 0.483, 0.567, 0.633, 0.917). Obviously, different mechanisms are involved in the creation of antioxidant properties in essential oil constituents.[17]

Table 3.

Results of MIC for J. excelsa essential oil

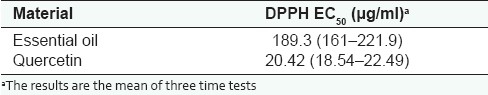

Table 4 depicts radical scavenging effect of essential oil of J. excelsa in comparison with standard of quercetin. The EC50 value of essential oil was found to be 189.3 (161-221.9), which showed a mild antioxidant activity while the EC50 of quercetin was 20.42 (18.54–22.49) μg/ml.

Table 4.

Antioxidant activity of J. excelsa essential oilª

In conclusion, the results show that the current essential oil may be a good candidate to be used in food industry.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (grant 3258).,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halliwell T, Gutteridge JMC. UK: Oxford University Press Oxford; 2003. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell JC. Food antioxidants: International perspectives welcome and indroductory remarks. Food Chem Toxicol. 1986;24:997–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarikurkcu C, Tepe B, Daferera D, Polissiou M, Harmandar M. Studies on the antioxidant activity of the essential oil and methanol extract of Marrubium globosum subsp. globosum (Lamiaceae) by three different chemical assays. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:4239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parke DV, Lewis DF. Safety aspects of food preservatives. Food Addit Contam. 1992;9:561–77. doi: 10.1080/02652039209374110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaieb K, Hajlaoui H, Zmantar T, Kahla-Nakbi AB, Rouabhia M, Mahdouani K, et al. The chemichal composition and biological activity of clove essential oil, Eugenia caryophyllata (Syzigium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): A short review. Phytother Res. 2007;21:501–6. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edris AE. Pharmaceutical and therapeutic potentials of essential oils and their indiviual volatile constitiuents: A reivew. Phytother Res. 2007;21:308–23. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topçu G, Erenler R, Cakmak O, Johansson CB, Celik C, Chai HB, et al. Diterpenes from the berries of Juniperus excelsa. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:1195–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asadi M. Tehran: Research Institute of Forest and Raglands; 1998. Flora of Iran, No. 21: Cupressaceae. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emami SA, Asili J, Mohagheghi Z, Hassanzadeh MK. Antioxidant activity of leaves and fruits of Iranian conifers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:313–9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burits M, Asres K, Bucar F. The antioxidant activity of the essential oils of Artemisia afra, Artemisia abyssinica and Juniperus procera. Phytother Res. 2001;15:103–8. doi: 10.1002/ptr.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loizzo MR, Tundis R, Conforti F, Saab AM, Statti GA, Menichini F. Comparative chemical composition, antioxidant and hypoglycaemic activities of Juniperus oxycedrus ssp. oxycedrus L. berry and wood oils from Lebanon. Food Chem. 2007;105:572–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soltanipour M. Final report of collection and identification of medicinal plants from Hormozgan province. Deputy of education and research of Jahad-e-Keshvarzi (Iranian Agricultural) Ministry. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams RP. Carol Stream, Illinois: Allurred Publication; 2004. Identification of Eseential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectorscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron EJ, Finegold SM. St. Louis: Mosby; 1990. Methods for tetsting antmicrobilal effectiveness. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner H, Bladt S. Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag Berlin; 2001. Plant Drug Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavin A, Potterat O, Wolfender JL, Hostettmann K, Dyatmyko W. Use of on-flow LC/H NMR for the study of an antioxidant fraction from Orophea enneandra and isolation of a polyacetylene, lignans, and a tocopherol derivative. J Nat Prod. 1998;51:1497–501. doi: 10.1021/np980203p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moein S, Farzami B, Khaghani S, Moein MR, Larijani MA. Antioxidant properties and protective effect on cell cytotoxicity of Salvia mirzayani. Pharm Biol. 2007;46:458–63. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filipowicz N, Kamiński M, Kurlenda J, Asztemborska M, Ochocka JR. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of juniper berry oil and its selected components. Phytother Res. 2003;17:227–31. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]