Abstract

Catharanthus roseus Linn (Apocynaceae), is a traditional medicinal plant used to control diabetes, in various regions of the world. In this study we evaluated the possible antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effect of C. roseus (Catharanthus roseus) leaf powder in diabetic rats. Diabetes was induced by intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ, 55 mg/kg body wt) to male Wistar rats. The animals were divided into four groups: Control, control-treated, diabetic, and diabetic-treated group. Diabetic-treated and control-treated rats were treated with C. roseus leaf powder suspension in 2 ml distilled water, orally (100 mg/kg body weight/day/60 days). In diabetic rats (D-group) the plasma glucose was increased and the plasma insulin was decreased gradually. In the diabetic-treated group lowering of plasma glucose and an increase in plasma insulin were observed after 15 days and by the end of the experimental period the plasma glucose had almost reached the normal level, but insulin had not. The significant enhancement in plasma total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL and VLDL-cholesterol, and the atherogenic index of diabetic rats were normalized in diabetic-treated rats. Decreased hepatic and muscle glycogen content and alterations in the activities of enzymes of glucose metabolism (glycogen phosphorylase, hexokinase, phosphofructokinase, pyruvate kinase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), as observed in the diabetic control rats, were prevented with C. roseus administration. Our results demonstrated that C. roseus with its antidiabetic and hypolipidemic properties could be a potential herbal medicine in treating diabetes.

Keywords: Anti Catharanthus roseus, plasma insulin, plasma lipids, STZ-induced diabetes

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia and disturbance of carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism along with long-term complications affecting the retina, kidney, and nervous system.[1] Different types of oral hypoglycemic agents such as biguanides and sulfonylurea are available along with insulin for the treatment of diabetes. Unfortunately, apart from having a number of side effects, none of the oral synthetic hypoglycemic agents have been successful in maintaining euglycemia or controlling long-term microvascular and macrovascular complications. Although insulin therapy is also used for management of diabetes mellitus, there are several drawbacks, such as, insulin resistance, anorexia nervosa, brain atrophy, and fatty liver after chronic treatment.[2] There is a growing interest in herbal remedies, because of their effectiveness, minimal side effects in clinical experience, and relatively low cost. Herbal drugs or their extracts are prescribed widely; even their biologically active compounds are unknown.[3] In many developing countries, traditional medicine, in particular the herbal medicine, is sometimes the only affordable source of healthcare.[4] Even the WHO (World Health Organization) approves the use of plant drugs for different diseases, including diabetes mellitus.[5] Therefore, studies with plant extracts are useful, to know their efficacy and mechanism of action and safety.

Catharanthus roseus L (Apocynaceae) is a subshrub also known as Medagaskar periwinkle, Vinca rosea or Lanchnera rosea worldwide. The plant Catharanthus roseus (C. roseus) has gained acceptance from the pharmaceutical industries, as it is widely used as an infusion in different parts of world, to treat diabetes.[6,7] The fresh juice from the flowers of C. roseus, made into a tea, has been used by Ayurvedic physicians in India for external use to treat skin problems, dermatitis, eczema, and acne. The ethanol extract of the C. roseus flower has been reported to have wound healing activity.[8] The sulfates of C. roseus alkaloids, vincristine and vinblastine, are widely used as chemotherapeutic agents against Leukemia and Hodgkin's disease worldwide.[9] Hot water decoction of the leaves and / or the whole plant is used for the treatment of diabetes in several countries.[10] Significant antihyperglycemic activities of the leaf alcoholic extract,[11,12] aqueous extract,[13] and the dichloromethane-methanol extract of leaves and twinges[14] have been reported in laboratory animals. Fresh leaf juice of C. roseus has been reported to reduce blood glucose in normal and alloxan diabetic rabbits.[15] Although, earlier reports indicate blood glucose lowering activity in alcoholic extracts of leaves, studies regarding C. roseus leaf powder efficacy in the management of hyperglycemia have not been undertaken. In the present study we evaluated the antidiabetic and hypolipidemic activity of C. roseus leaf powder suspension in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Streptozotocin, lactate dehydrogenase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase were obtained from the Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and procured from Sisco Research Laboratories (P) Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Plant material

Catharanthus roseus (white variety) was taxonomically authenticated by the Department of Botany, Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Anantapur, and the voucher specimen was kept in the herbarium (No. 2235) of our University. Fresh leaves of C. roseus (white variety) were collected during September, from the University campus, and the leaves were shade dried and then grinded to fine powder.

Induction of diabetes to experimental animals

Two-to-three-month-old male albino Wistar rats of body weight 150 – 180 g were procured from Sri Venkateswara Enterprises (Bangalore, India), acclimatized for seven days to our animal house, and maintained at standard conditions of temperature and relative humidity, with a 12-hour light / dark cycle. Water and commercial rat feed were provided ad libitum. The current study was carried out with prior permission from our Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (Regd. no. 470/01/a/CPCSEA, dt. 24 August, 2001). Diabetes was induced in overnight fasted rats by a single intraperitoneal injection of freshly prepared STZ (55 mg/kg body weight, in ice-cold 0.1 M citrate buffer, pH 4.5, in a volume of 0.1 ml per rat). Seventy-two hours after STZ administration, the plasma glucose level of each rat was determined, for confirmation of diabetes. Rats with plasma glucose level above 250 mg/dl were considered as diabetics and used subsequently.

Experimental design and biochemical analysis

In the present experiment, a total of 32 rats (16 diabetic surviving rats; 16 normal rats) were used. The rats were divided into four groups of eight each: control (C); control rats treated with C. roseus (C + CR); diabetic (D), and diabetic animals treated with C. roseus (D + CR). Diabetic-treated group and C + CR-group received C. roseus leaf powder suspension (100 mg/kg body weight) in 2 ml distilled water daily, for 60 days, through oral intubation, whereas, 2 ml of distilled water was administered to D + CR and C + CR rats. Based on the preliminary experiments on the dose-dependent antihyperglycemic effect of leaf powder, a dose less than 100 mg/kg body weight was not found to be effective in rats. Body weight was monitored at 15-day intervals. During the experimental period, blood was collected from 12-hour fasted rats by means of a capillary tube through the orbital sinus, at 15-day intervals. Plasma glucose was estimated by the glucose oxidase-peroxidase (GOD-POD) method, by using the Span diagnostic kit (Span diagnostic Ltd., Surath, India). Triglycerides, total cholesterol, and HDL-cholesterol were measured by enzymatic colorimetric end point methods using the Span diagnostic reagent kit. LDL and VLDL-cholesterol were obtained by calculations using the formula provided in the cholesterol diagnostic kit booklet. Plasma insulin was estimated by using the radioimmunoassay kit (RIA K-1) from the Bhabha Atomic Research Center (Mumbai, India).

Animal sacrifice

Animals from each experimental group were starved for 16 hours and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The liver, muscle, and kidneys were removed, washed thoroughly with ice-cold saline and used for analysis.

Glycogen content

Glycogen released from a protein-free supernatant of trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-homogenized tissues were precipitated with 95% ethanol. The precipitated glycogen was then hydrolyzed under acidic condition and the liberated glucose was estimated by the Anthrone method as adapted by Carrol et al.[16]

Assay of carbohydrate metabolism enzymes

Liver and muscle homogenates were prepared in 0.1M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and used for assay of hexokinase (HK),[17] phosphofructokinase PFK,[18] and pyruvate kinase (PK),[18] and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH)[19] and glycogen phospharylase,[20] were assayed.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as means ± S.E. Data were analyzed for significant differences using Duncan's Multiple Range (DMR) test. (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Body weight

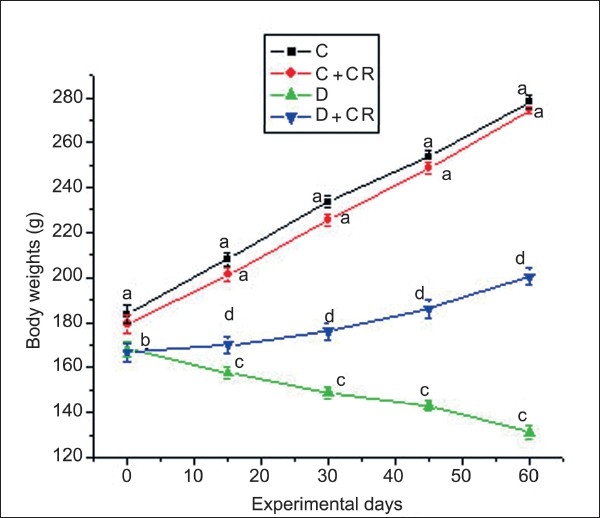

Characteristic symptoms of diabetes such as loss of body weight, polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria observed in the D-group, were rectified in the D + CR-group. At the end of the 60-day experimental period, the D-group showed 21.9% reduction in body weight, whereas, the C, C + CR, and D + CR-groups showed an increase in body weight of 51.4, 53, and 20.2%, respectively [Figure 1]. However, by the end of the experimental period the D + CR-group showed a significant increase (52.8%) in body weight when compared to the D-group.

Figure 1.

Mean body weight of C, C + CR, D, and D + CR groups during the experimental period. Values are ± S.E., (n = 8 animals). Values not sharing common letters differ significantly at P < 0.05 (D.M.R test) among four experimental groups during the corresponding period.

Plasma glucose and insulin

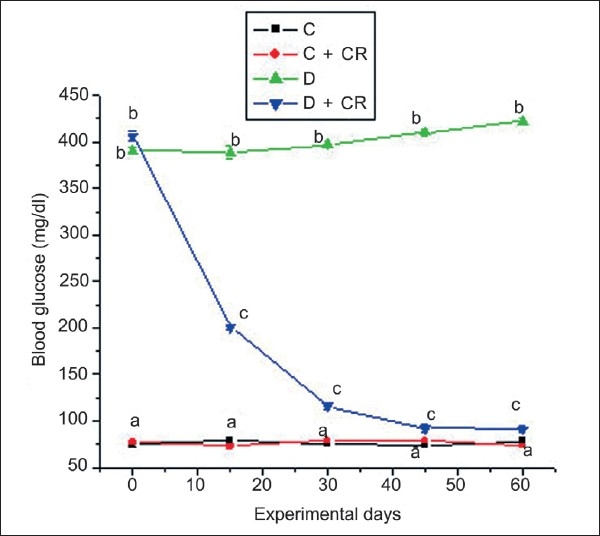

Data on the plasma glucose content of the four experimental groups are presented in Figure 2. Group-C and C + CR-rats remained persistently euglycemic throughout the experimental period. In the D-group, the plasma glucose level gradually increased during the experimental period from 390.87 ± 1.18 to 420.25 ± 2.8 mg/dl. A significant antihyperglycemic effect was evident in the D + CR-group from 15 days onwards and the decrease in plasma glucose was 77.7% by 60 days of treatment.

Figure 2.

Mean plasma glucose of C, C + CR, D, and D + CR groups during the experimental period. Values are ± S.E., (n = 8 animals). Values not sharing common letters differ significantly at P < 0.05 (D.M.R test) among four experimental groups during the corresponding period.

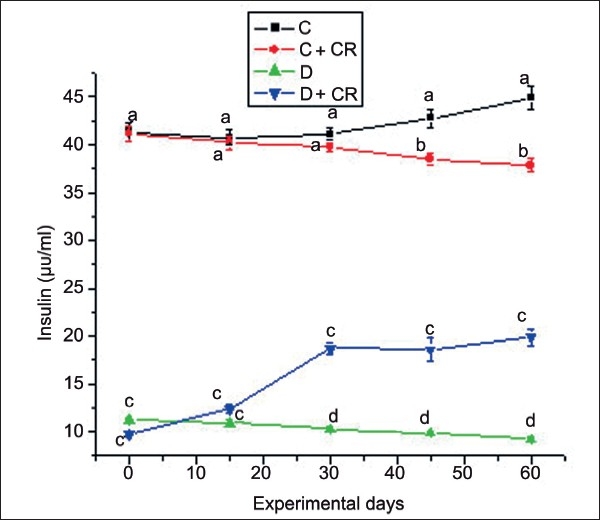

The fasting plasma insulin levels of the four groups of animals during the experimental period are presented in Figure 3. The Control-treated group showed statistically lower insulin levels at 45 and 60 days when compared with the C-group. By the end of the experimental period, D-group plasma insulin was decreased from 11.2 ± 0.18 to 9.33 ± 0.2 μU/ml. Group-D + CR showed significantly higher concentration of insulin at 15 days (12.39 ± 0.5), 30 days (18.70 ± 0.6), 45 days (18.62 ± 0.6), and 60 days (19.87 ± 0.8) with 13.7, 82, 87.7, and 109.1% increase, respectively, when compared with D-group. At the end of experimental period the insulin level of the D + CR-group was significantly higher than the D-group, but still significantly lower than the C-group.

Figure 3.

Mean plasma insulin of C, C + CR, D, and D + CR groups during the experimental period. Values are ± S.E., (n = 8 animals). Values not sharing common letters differ significantly at P < 0.05 (D.M.R test) among four experimental groups during the corresponding period.

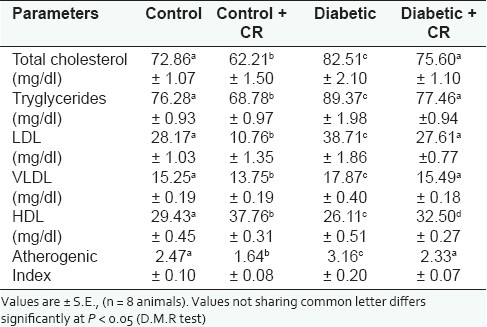

Plasma lipid profile

The plasma lipid profiles of the four groups of animals during the experimental period are represented in Table 1. A significant increase in the plasma total cholesterol (13.2%), triglycerides (17.2%), LDL-cholesterol (37.4%), and VLDL-cholesterol (17.2%), and a significant decrease in HDL-cholesterol (11.31%) in the D-group compared to the C-group, resulted in a significant increase in the atherogenic index (27.9%). A significant decrease in plasma total cholesterol (14.6%), triglycerides (9.8%), LDL-cholesterol (61.8%), VLDL-cholesterol (9.84%), and a significant increase in the HDL-cholesterol concentration (28.3%) in the C + CR-group compared to the C-group resulted in a significant decrease in atherogenic index (33.5%). Group D + CR showed a significant decrease in plasma total cholesterol (8.4%), triglycerides (13.3%), LDL-cholesterol (28.7%), VLDL-cholesterol (13.3%), and the atherogenic index (28.7%), and a significant increase in HDL-cholesterol concentration (24.5%) when compared with the D-group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of C. roseus leaf powder treatment on plasma lipid profile

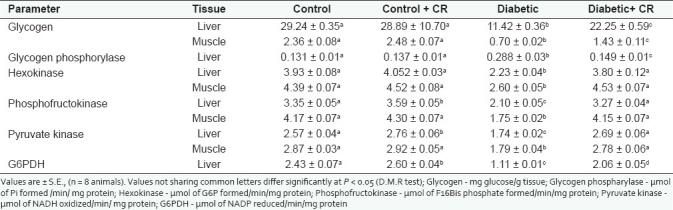

Glycogen

Group-D showed significantly decreased glycogen content in the liver (60.9%) and muscle (70.3%), when compared to the C-group. In the D + CR-group C. roseus treatment resulted in a significant enhancement in the liver (94.8%) and muscle (104%) glycogen content when compared to the D-group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Effect of C. roseus leaf powder treatment on glycogen and some carbohydrate metabolic enzymes

Carbohydrate metabolism enzymes

Table 2 shows activities of carbohydrate metabolic enzymes in the liver and muscle. The STZ diabetic rats (D-group) showed a significantly enhanced hepatic glycogen phosphorylase activity (119.4%) compared to the C-group. The D + CR rats showed decreased activity (48.3%) of glycogen phosphorylase compared to the D-group rats. The STZ-induced diabetic rats showed significantly decreased activities of glycolytic enzymes, both in the liver and muscles, compared to the control rats. The percent decrease in HK, PFK, and PK activities in the liver and muscle of the D-group are 43.2, 37.3, and 32.2%, and 40.7, 58.1, and 37.6%, respectively. C. roseus treated diabetic rats, that is, the D + CR-group showed no deviation in the activities of HK, PFK, and PK, both in the liver and muscle compared to the C-group. Thus C. roseus treatment in the D + CR-group prevented diabetic-induced alterations in the glycolytic enzyme activities. Hepatic G6PDH activity decreased significantly (54.3%) in the D-group. C. roseus treatment resulted in a significant enhancement in the activity of G6PDH in the liver of the C + CR and D + CR-groups (7.0 and 85.5%) compared to the C and D-groups, respectively.

DISCUSSION

As expected, STZ-induced D-group rats showed characteristic signs of diabetes such as, polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria, failure to gain in body weight, hyperglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, and hyperlipidemia. Inspite of polyphagia, a decrease in the body weight of diabetic rats was possible due to excessive catabolism of fats and protein.[21] In the D + CR-group, ingestion of C. roseus leaf powder effectively prevented these diabetic symptoms, indicating the antidiabetic nature of this plant. No visible side effects of C. roseus leaf powder were observed in the C + CR-group, representing the non-toxic nature of C. roseus. The plasma glucose levels observed in the C + CR and D + CR-groups during the experimental period clearly indicate that C. roseus leaf powder does not promote hypoglycemic activity, but exerts an antihyperglycemic effect. Chronic treatment of diabetic rats for a 60-day period with C. roseus leaf powder lowered the plasma glucose level to near normal levels. The gradual decrease in the plasma insulin levels of the C + CR-rats during the experimental period resulted in significantly lower values at 45 and 60 days compared to C-rats in the corresponding period. This result with the maintained normoglycemia [Figure 2] in C + CR-rats indicates that C. roseus promotes glucose uptake by promoting insulin sensitivity. In the STZ-induced diabetic model, insulin is markedly depleted, but not absent.[22] The hypoinsulinemia observed in STZ-induced diabetic rats is gradually intensified during the experimental period. A significant increase in the plasma insulin levels of the D + CR-group compared to the D-group may be due to the regeneration of the STZ-destructed β-cells, which is probably due to the fact that the pancreas contains stable (quiescent) cells that have the capacity to regenerate.[23,24] Therefore, the surviving cells can proliferate to replace the lost cells. Phytochemicals such as flavonoids and alkaloids present in the C. roseus leaf powder[25] may have protected the intact functional β-cells from further deterioration through oxidative stress. Hence, the β-cells remain active and continue to produce insulin. It is also claimed that antioxidants such as flavonoids are possibly beneficial in preventing STZ-induced diabetes by stopping oxidative damage of the pancreas, and increasing insulin secretion by the regeneration of pancreatic β-cells.[26,27]

In this study, we have noticed elevated levels of plasma lipids such as total cholesterol, LDL and VLDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides and decreased level of HDL-cholesterol in the D-group, which are risk factors for coronary heart disease.[28] Insulin increases uptake of fatty acids into the adipose tissue and increases triglyceride synthesis.[29] Moreover, insulin inhibits lipolysis. Lipolysis is not inhibited in the D-group due to the presence of insulin deficiency, leading to hyperlipidemia. It is interesting that treatment with C. roseus leaf powder suspension for 60 days brings down the elevated levels of total cholesterol, LDL and VLDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides, and also increases plasma HDL-cholesterol to normal levels in D + CR-rats, indicating the beneficial effect of C. roseus in reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Increased levels of HDL-cholesterol, an antiatherogenic lipoprotein, after C. roseus administration may be due to an increase in the activity of lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase, which may contribute to the regulation of blood lipids.[30]

The liver plays an important role in buffering postprandial hyperglycemia and is involved in the synthesis of glycogen. Diabetes mellitus is known to impair the normal capacity of the liver to synthesize glycogen.[31] Assessment of glycogen levels serve as a marker for studying the antidiabetic activity of C. roseus. In the D-group, the glycogen content in the liver and muscle was reduced compared to control rats. This is in line with previous studies on STZ-diabetic rats.[32] Two months of treatment with C. roseus partially prevented the depletion of glycogen in the liver and muscle of STZ-diabetic rats. This could be due to the increased circulatory insulin concentrations observed in the D + CR-group compared to the D-group. Increased activity of hepatic glycogen phosphorylase observed in STZ-diabetic rats might be one contributing factor for the decreased hepatic glycogen content. The elevated hepatic glycogen content and decreased plasma glucose levels of C. roseus-treated, STZ-diabetic rats compared to STZ-diabetic control rats could be explained by the diminished activity of the glycogenolytic enzyme, namely, glycogen phosphorylase.

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by partial or total deficiency of insulin, resulting in derangement of carbohydrate metabolism and a decrease in the enzymatic activity of HK and PFK, resulting in the depletion of liver and muscle glycogen.[33] As insulin administration normalizes these alterations in the enzymatic activities, these enzymes represent a method to assess the peripheral utilization of glucose. Glycolytic enzymes (HK, PFK, PK) activity of the D-group was significantly decreased in the liver and muscle, and this was similar to the previous findings.[34,35] An increase in the activity of glycolytic enzymes in C. roseus-treated diabetic rats implied that the cellular entry of glucose was facilitated by C. roseus, which in turn stimulated the activity of these enzymes. This glucose influx is due to an increase in the circulation of insulin and insulin sensitivity. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is the key regulating enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway and controls the flow of carbon through this pathway. Specifically, the enzyme catalyzes the first reaction in the pathway leading to the production of pentose phosphates and reduces power in the form of Nicotinamide Adenosine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) for reductive biosynthesis and maintenance of the redox state of the cell. Alterations in G6PDH activity can significantly alter oxidative stress-induced cell death.[36] C. roseus administration increases the G6PDH activity in D + CR- rats. Insulin is reported to stimulate oxidation of glucose by increasing the activation of G6PDH in a dose-dependent manner.[37] Thus, the increased circulatory insulin level observed in C. roseus-treated STZ-diabetic rats may cause increased activity of G6PDH in these rats.

Based on our observations of carbohydrate metabolism, the antihyperglycemic effect of this plant appears to be at least in part, due to extra pancreatic activity, including increased glucose utilization by the liver and muscle (glycolysis), enhanced glucose oxidation through shunt pathway, via activation of G6PDH, and decreased glucose production by depression of glycogenolytic enzyme.

CONCLUSIONS

Thus our findings show that oral administration of C. roseus leaf powder produces an antihyperglycemic effect, lowers both total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and at the same time increases HDL-cholesterol in STZ-induced diabetic rats. The antihyperglycemic action of the leaf powder of C. roseus is associated with increased plasma insulin concentration and insulin sensitivity. This investigation shows the potential of C. roseus, for use as a natural oral agent, with both antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects. Further comprehensive biochemical and pharmacological investigations are needed to elucidate the exact mechanism of the antihyperglycemic effect of C. roseus.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the National Center for Laboratory Animal Sciences, Hyderabad, for the kind supply of feed for the experimental animals. Thanks are also due to Prof. Ch. Appa Rao, K. Ramesh Babu, and Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati, for their help in the insulin assay.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. New diagnostic criteria and classification of diabetes-again. Diabet Med. 1998;15:535–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<535::AID-DIA670>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piédrola G, Novo E, Escobar F, García-Robles R. White blood cell count and insulin resistance in patients with coronary artery disease. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2001;62:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valiathan MS. Healing plants. Curr Sci. 1998;75:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamdan II, Afifi FU. Studies on the in vitro and in vivo hypoglycemic activities of some medicinal plants used in treatment of diabetes in Jordanian traditional medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Publications; 2002. WHO. Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-2005; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alxeandrova R, Alxeandrova I, Velcheva M, Varadino T. Phytoproducts and cancer. Exp Patho Parasitol. 2000;4:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijden R. V, Jacob D.I, Soneijer W., Hallard D., Verpoorte R. The Catharanthous alkaloids: Pharmacognosy and biotechnology. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:607–28. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayak BS, Pinto Pereira LM. Catharanthus roseus flower extract has wound-healing activity in Sprague Dawley rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozgen U, Türköz Y, Stout M, Ozuğurlu F, Pelik F, Bulut Y, et al. Degradation of vincristine by myeloperoxidase and hypochlorous acid in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2003;27:1109–13. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(03)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Don G. Catharanthus roseus. In: Ross IA, editor. Medicinal Plants of the World. Totowa: Human Press; 1999. pp. 109–18. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chattopadhyay RR. A comparative evaluation of some blood glucose lowering agents of plant origin. J Ethanopharmacol. 1999;67:367–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mostofa M, Choudhury ME, Hossain MA, Islam MZ, Islam MS, Sumon MH. Antidiabetic effects of Catharanthus roseus, Azadirachta indica, Allium sativum and glimepride in experimentally diabetic induced rat. Bang J Vet Med. 2007;5:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam A, Akhtar AM, Khan MR, Hossain MS, Alam MK, Wahed MI, et al. Antidiabetic and hypolipidemic effects of different fractions of Catharanthus roseus (Linn.) on normal and Streptozotocin-induced diabetic Rats. J Sci Res. 2009;1:334–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somananth S, Praveen V, Shoba S, Radhey S, Kumari MM, Ranganathan S, et al. Effect of an antidiabetic extract of a Catharanthus roseus on enzymatic activities in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Ethanopharmacol. 2001;76:269–77. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nammi S, Boini MK, Lodagala SD, Behara RB. The fresh leaves of Catharanthus roseus Linn. Reduces blood glucose in normal and alloxan diabetic rabbits. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2003;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrol NV, Longley RW, Roe JH. The determination of glycogen in liver and muscle by use of anthrone reagent. J Biol Chem. 1956;220:583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Easterby JS, Qadri SS. Hexokinase Type II from rat skeletal muscle. In: Colowick SP, Kaplan, editors. Methods Enzymol. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadava D, Alonso D, Hong H, Pettit-Barrett DP. Effect of methadone addiction on glucose metabolism in rats. Gen Pharmacol. 1997;28:27–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beutler E. 2nd ed. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1975. Red cell metabolism. A Manual of Biochemical methods; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutherland EW. Methods in Enzymol 2. In: Colowick SP, Kaplan, editors. New York: Academic Press New York; 1955. pp. 215–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vats V, Yadav SP, Grover JK. Ethanolic extract of Ocimum sanctum leaves partially attenuated streptozotocin-induced alterations in glycogen content and carbohydrate metabolism in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pushparaj PN, Tan BK, Tan CH. The mechanism of hypoglycemic action of the semi purified fractions of Averrhoa bilimb in streptozotocin diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2001;70:535–47. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee M, Kanitkar M, Bhonde RR. Approaches towards endogenous pancreatic regeneration. Rev Diabet Stud. 2005;2:165–76. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2005.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cano DA, Rulifson IC, Heiser PW, Swigart LB, Pelengaris S, German M, et al. Regulated β-cell regeneration in the adult mouse pancreas. Diabetes. 2008;57:958–66. doi: 10.2337/db07-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa NR, Verpoorte R. Phenolic compounds in Catharanthus roseus. Phytochem Rev. 2007;6:243–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamalakkannan N, Prince PS. Antihyperglycaemic and antioxidant effect of rutin, a polyphenolic flavonoid, in streptozotocin-Induced diabetic Wistar rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishore A, Nampurath GK, Mathew SP, Zachariah RT, Potu BK, Rao MS, et al. Antidiabetic effect through islet cell protection in streptozotocin diabetes: A preliminary assessment of two thiazolidin-4-ones in Swiss albino mice. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;177:242–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD. Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded. Findings in 356 primary screens of the multiple risk factor intervention trial (MR-FIT)? JAMA. 1986;256:2823–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirwaikar A, Rajendran K, Dinesh Kumar C, Bodla R. Antidiabetic activity of aqueous extract of Annona squamosa in streptozotocin-nicotinamide type 2 diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil UK, Saraf S, Dixit VK. Hypolipidemic activity of seeds of Cassia tora Linn. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:249–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitton PD, Hems DA. Glycogen synthesis in the perfused liver of streptozotocin diabetic rats. Biochem J. 1975;150:153–65. doi: 10.1042/bj1500153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vats V, Yadav SP, Grover JK. Effect of Trigonella foenumgraceum on glycogen content of tissues and the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:237–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy ED, Anderson JW. Tissue glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzyme activities in mildly and moderately diabetic rats. influence of tobutamide administration. Endocrinology. 1974;94:27–34. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grover JK, Vats V, Rathi SS. Anti-hyperglycemic effects of Eugenia jambolana and Tinospora cordifolia in experimental diabetes and their effects on key metabolic enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73:461–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathi SS, Grover JK, Vats V. Anti-hyperglycemic effects of Momordica charantia and Mucuna pruriens in experimental diabetes and their effect on key metabolic enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Phytother Res. 2002;16:236–43. doi: 10.1002/ptr.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vulliamy T, Mason P, Luzzatto L. The molecular basis of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Trends Genet. 1992;8:138–43. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90372-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagle A, Jivraj S, Garlock GL, Stapleton SR. Insulin regulation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase gene expression is rapamycin-sensitive and requires Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14968–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]