Summary/Abstract

This method describes a rapid and efficient approach for solid phase synthesis of N-linked glycopeptides which utilizes on-resin glycosylamine coupling to produce N-linked glycosylation sites (1). In this method, the full-length non-glycosylated peptide is first synthesized on solid phase using standard Fmoc chemistry. The glycosylation site is then introduced through an orthogonally protected 2-phenylisopropyl (PhiPr) Aspartic acid (Asp) residue. After selective deprotection of the Asp residue, a high mannose oligosaccharide glycosylamine is coupled on-resin to the free Asp side chain to form a N-glycosidic bond. Subsequent protecting group removal and peptide cleavage from the resin yield the desired glycopeptide. This strategy provides effective glycosylation reactions on the solid phase, simplifies glycopeptide purification relative to solution phase glycopeptide synthesis strategies, and enables recovery of potentially valuable, un-reacted oligosaccharides. This approach has been applied to the solid phase synthesis of the N-linked high mannose glycosylated form of peptide T (ASTTTNYT), a fragment of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 (2–3).

Keywords: N-linked glycopeptide, solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), high mannose oligosaccharide, 2-phenylisopropyl protecting group, glycosylamine, peptide T, HIV, gp120

1. Introduction

Homogenous N-linked glycopeptides are valuable materials for biochemical, structural and medicinal studies to help understand the specific roles of N-linked glycosylation (4) and facilitate the development of N-linked glycopeptide based vaccines and therapeutics (5). However, the starting materials of glycopeptide synthesis, large N-linked oligosaccharides, are often difficult to obtain from biological systems and are also difficult to chemically synthesize (6–11). In addition, the coupling of large, bulky N-linked oligosaccharides to peptides can be a low yielding reaction that is prone to aspartimide formation (12–13). Because of this it is crucial to utilize an efficient method for N-linked glycopeptide synthesis which does not waste valuable N-linked oligosaccharide starting materials.

The method of N-linked glycopeptide synthesis (1) described here effectively combines the advantages of both solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) (14) and in-solution Lansbury aspartylation (15–16) by introducing the glycosylation site via glycosylamine coupling to partially protected, full-length peptides on solid phase support (1). As described in Fig. 1, the full length non-glycosylated peptide sequence is first built via SPPS. At the desired glycosylation site, a 2-phenylisopropyl (PhiPr) (17) orthogonally protected Asp residue is incorporated. The PhiPr protecting group efficiently suppresses aspartimide formation during the construction of the peptide unlike other orthogonal protecting groups such as allyl esters (1, 18–20). Next, the PhiPr protecting group is selectively removed on-resin to free the carboxylic acid side chain of the Asp residue, which allows the introduction of the N-linked oligosaccharide. Then a glycosylamine, such as Man8GlcNAc2NH2, 2, is coupled to the free Asp side chain on-resin. This key step has been optimized for both the monosaccharide N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAcNH2) and a high mannose oligosaccharide (Man8GlcNAc2NH2, 2) on aspartimide prone peptide sequences, and satisfying glycosylation yields have been achieved (1). At the end of the synthesis, final deprotection and resin cleavage provide the desired N-linked glycopeptide. An important aspect of this strategy is that excess N-linked oligosaccharides can be utilized to drive the glycosylation reaction on-resin and un-reacted, valuable oligosaccharide can be conveniently recovered after the on-resin glycosylamine coupling reaction by filtration and silica gel purification. The recovered oligosaccharide can then be reused in later syntheses, increasing the efficiency of this method (1).

Fig. 1.

Strategy for on-resin convergent synthesis of N-linked high mannose oligosaccharide containing glycopeptides.

Here this strategy for N-linked glycopeptide synthesis is demonstrated by the synthesis of a glycosylated form of peptide T (ASTTTNYT) containing the high mannose oligosaccharide Man8GlcNAc2, 1. Peptide T is a fragment of the HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 consisting of residues 185 to 192 which contains a naturally occurring N-linked glycosylation site consensus sequence (2–3).

2. Materials

Ammonium hydrogen carbonate (Mallinckrodt Chemicals AR® ACS).

Milli-Q water (purified and deionized by Millipore water purification system).

Normal amino acid building blocks: amino acids side chains are protected by the most commonly used protecting groups, including tert-butyl (tBu) for Tyr, Ser, Thr, Glu and Asp; 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Pbf) for Arg; trityl (trt) for Gln, Asn and Cys, His; tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) for Trp (AAPPTEC).

Fmoc-Asp(O-2PhiPr)-OH (EMD Biosciences).

Man8GlcNAc2 (produced in yeast, see Note 1)

3-(Diethoxyphosphoryloxy)-1, 2, 3-benzotriazin-4(3H)-one (DEPBT) (AAPPTEC).

1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) (AnaSpec. Inc.)

N,N'-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC) (AnaSpec. Inc.).

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Acetic anhydride (Mallinckrodt Chemicals AR® ACS).

N-methylmorpholine (NMM) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Piperidine (Sigma-Aldrich).

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (J.T. Baker analyzed® reagent 99.9%).

Dichloromethane (DCM) (Mallinckrodt Chemicals ChromAR®).

Dimethylformamide (DMF) (Mallinckrodt Chemicals ChromAR®).

Methyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99.9%) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Acetonitrile (0.1% TFA in Acetonitrile, for HPLC and Spectrophotometry Honeywell Buidick & Jackson®).

Triisopropylsilane (TIS) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Diethyl ether anhydrous (ether absolute, EMD).

Methanol (J.T. Baker analyzed® HPLC solvent).

Ethyl acetate (Mallinckrodt Chemicals AR® ACS).

Rink Amide PEGA resin (50–100 mesh, 0.20–0.50 mmol/g) (EMD Biosciences).

Poly-Prep® Chromatography Columns (0.8×4 cm Bio-Rad)

Pierce Economy Mini-Spin Columns (0.8mL resin capacity) (Thermo Scientific).

Silica gel 62, 60–200 mesh (EMD).

Silica gel TLC plates (EMD Chemical, Si 60 F254).

Ninhydrin test solutions (A: dissolve 40 g phenol in 20 ml ethanol; B: add 1 ml KCN buffer (dissolve 16.5 mg KCN in 25 ml water ) into 49 ml pyridine; C: dissolve 1.0 g ninhydrin in 20 ml ethanol) (21).

Vanillin staining solution (15g vanillin in 250mL ethanol and 2.5mL concentrated sulfuric acid.).

Phenol-sulfuric acid test recipe (50 µL concentrated sulfuric acid, 20 µL sample and 1 µL phenol) (22).

Fmoc peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems 433A Peptide Synthesizer).

Semi-preparative RP-HPLC systems (Hyper prep 120 C18 8µ, Length 250 mm, I.D. 10 mm).

Lyopholizer (VirTis Sentry 2.0).

3. Methods

The following method based upon the work reported by Chen and Tolbert (1) describes the on-resin convergent synthesis of high mannose containing N-linked glycopeptides. The individual procedures consist of (1) preparation of glycosylamines from free reducing end sugars, (2) solid phase synthesis of a full length non-glycosylated peptide, in which an Asp residue is protected orthogonally by the PhiPr group at the desired glycosylation site, (3) selective deprotection of the Asp side chain, (4) on-resin coupling of the glycosylamine, (5) final deprotection, resin cleavage and purification, (6) recovery of un-reacted high mannose oligosaccharide.

3.1. Preparation of glycosylamines

The conversion of free reducing end sugars into their corresponding glycosylamines is accomplished by treatment with saturated, aqueous ammonium hydrogen carbonate at room temperature (23). The residual ammonium hydrogen carbonate is removed by repetitive rotatory evaporation and lyophilization to give the desired glycosylamine for direct use in glycosylation reactions without further purification. The percentage of glycosylamine conversion can be monitored by 1H-NMR during this process.

The free reducing end sugar, Man8GlcNAc2, 1 (20 to 100 mg), was dissolved in 25 mL of a saturated, aqueous ammonium hydrogen carbonate solution (produced with Milli-Q water) and stirred for 5–6 days at room temperature.

1H-NMR was utilized to monitor the reaction and showed the conversion of free sugar into its corresponding β-D-glycosylamine with a very high yield (see Fig. 2).

The reaction solution was diluted with Milli-Q water and rotatory evaporated at room temperature to dryness. This step was repeated multiple times to remove the residual ammonium hydrogen carbonate.

The sample was dissolved in Milli-Q water again and lyophilized repeatedly until the sample reached constant mass.

Glycosylamines prepared in this manner can be stored at −20°C in a desiccator for later use.

Fig. 2.

Expanded 400 Hz 1H-NMR spectra (in D2O) of a) free reducing end Man8GlcNAc2 1, and b) the resulting glycosylamine Man8GlcNAc2NH2 2 produced after 5 days treatment of 1 with saturated aqueous ammonium hydrogen carbonate.

3.2. Solid phase synthesis of full length non-glycosylated peptides

Synthesis of full length protected non-glycosylated peptides is carried out on a Fmoc Peptide Synthesizer using standard Fmoc methods utilizing DIC/HOBt coupling on Rink Amide PEGA resin. Manual coupling and capping is preferred for the loading of the first amino acid residue. At the desired glycosylation site, Fmoc-Asp(O-2PhiPr)-OH is added in the sequence to allow for selective deprotection after the peptide is synthesized for the introduction of glycosylation.

Rink Amide PEGA resin 0.001–0.01 mmole (see Note 2) was washed with DMF and then pre-swelled in DMF in a Poly-Prep® Chromatography column which was utilized as the reaction vessel. After half an hour, the DMF was drained off.

The first Fmoc-amino acid (5 equivalents) and 5 equivalents of DEPBT were dissolved in a minimum volume of DMF, and then added into the reaction vessel. Then, 3 equivalents of DIEA were added.

The reaction vessel was capped and attached on to a rotator. The rotator was rotated at 30 rpm at room temperature for approximately 3 hours. A ninhydrin test (see Note 3) was then utilized to determine the completion of the amino acid loading. The resin was washed consecutively with DMF (2 times), dry DCM (3 times) and then DMF again (2 times).

Treatment with a large excess of acetic anhydride (1.5 ml) with 3 equivalents of N-methylmorpholine in DCM for 45 min was then used to cap the un-reacted amino groups.

The resulting resin was then washed consecutively with DMF (2 times), dry DCM (3 times) and then DMF again (2 times). Fmoc protecting groups were removed using 20% piperidine in DMF (10 min × 3). The loading of the first amino acid residue was determined (see Note 4) by UV monitoring the Fmoc removal at 301 nm (ε=7800 cm−1M−1)(24).

The resin was then transferred into the reaction vessel of a Fmoc peptide synthesizer. Subsequent synthesis of peptides was carried out on the Fmoc Peptide Synthesizer by standard Fmoc methods utilizing DIC/HOBt. At the glycosylation site, Fmoc-Asp(O-2PhiPr)-OH was incorporated. All the other amino acids side chains were protected by the most commonly used protecting groups used in Fmoc SPPS. The N-terminal Fmoc was kept on the peptide at the end of synthesis.

The resin was then washed consecutively with DMF (2 times), dry DCM (3 times), DMF (2 times) and finally dry DCM, and transferred into a Poly-Prep® Chromatography column for the next reaction step. The resin can also be stored at −4°C for later use.

3.3. Selective deprotection of the Asp side chain

The PhiPr protected Asp residue is selectively deprotected by treatment with 1% TFA in DCM. Under these conditions other amino acid side chains remain protected, thereby selectively creating a free carboxylic acid at the site where glycosylamine coupling will be utilized to create a N-linked glycosylation site. (see Note 5)

The resin from step (2) was swelled with DCM in the reaction column for 10 min. Excess DCM was then removed.

The reaction column was filled with a solution of DCM/TFA/TIS (94:1:5), capped and shaken for 3 min. The reaction solution was then drained off. This step was repeated three times.

The resin was then washed excessively with DCM (5 times), DMF (5 times) and DMSO (5 times).

The selectively deprotected resin was then transferred into a Pierce Economy Mini-Spin Column for the next reaction.

3.4. On-resin coupling of the glycosylamine

On-resin glycosylamine coupling is the key step of this glycopeptide synthesis method. The prepared glycosylamine, in this case glycosylamine 2, is coupled to the free Asp acid side chain, which was selectively deprotected in step (3), to form a N-linked glycosidic bond on the resin bound peptide. This step is carried out in a Mini-Spin column to minimize the reaction volume. The reaction conditions, including coupling reagents, solvents, resins, amounts of base and equivalents of glycosylamines were optimized as described previously (1).

The selectively deprotected resin from step (3) was swelled with DMSO in the mini reaction column for 10 min. Excess DMSO was then removed.

3 equivalents of glycosylamine 2 and 3 equivalents of DEPBT were dissolved in a minimum amount of DMSO (100–200 µL) in separate eppendorf tubes, and then added into the mini reaction column. A minimum amount of DMSO was then used to rinse the residual glycosylamine left in the eppendorf tube, and this was also added into the reaction column. The total reaction volume was kept at less than one third of the capacity of the mini-spin column. (see Note 6)

The reaction column was attached to a rotator and the coupling reaction was rotated at 30 rpm at room temperature for 12 hours. (see Note 7)

The reaction solution was collected by centrifugation and filtration. The resin was then washed with DMSO (2 times) and the wash solution was combined with reaction solution. These solutions can be utilized to recover unreacted high mannose oligosaccharide as described in step (6). Then, the resin was washed with DMF (3 times), dry DCM (3 times), and DMF (2 times).

The resin was transferred into a Poly-Prep® Chromatography column for step (5), final deprotection and resin cleavage.

For the purpose of determining glycosylation yields, the crude peptides without removal of the N-terminal Fmoc protecting groups were cleaved from a resin sample, precipitated, washed twice with anhydrous diethyl ether, and then analyzed by analytical HPLC. The glycosylation yields were determined by analytical HPLC signals at 254 nm (see Fig. 3). (see Note 8)

Fig. 3.

Analytical HPLC for crude peptides after on-resin coupling of glycosylamine Man8GlcNAc2NH2 2 to the peptide Fmoc-ASTTTNYT, showing a 65% glycosylation yield.

3.5. Final deprotection, resin cleavage and product purification

The final glycopeptide product is obtained using the following steps. The N-terminal Fmoc is first removed using 20% piperidine in DMF. The glycopeptide is then fully deprotected and cleaved off resin by treatment with neat TFA containing 1% TIS scavenger. Crude glycopeptide after resin cleavage is purified by diethyl ether precipitation and then RP-HPLC.

The resin from step (4) was swelled with DMF for 10 min in the reaction column. DMF was then drained off.

The reaction column was filled with a solution of 20% piperidine in DMF, capped and rotated at 30 rpm for 10 min. The resin was then washed with DMF. This step was repeated twice and then a Ninhydrin test was utilized to confirm the removal of the Fmoc protecting group.

The resin was then washed thoroughly with DMF (3 times), dry DCM (2 times), DMF (3 times) and dry DCM (2 times).

The reaction column was then filled with a solution of TFA containing 1% TIS scavenger and sealed. This step was carried out stationarily for 2–3 hours.

The TFA solution was collected by filtration and rotatory evaporated to a volume of about 2 ml. Excess of diethyl ether anhydrous was added to precipitate peptides cleaved from the resin in this solution. The ether solution was placed at −20°C for half an hour to allow maximum precipitation.

The ether solution was centrifuged at 10k rpm in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The supernatant was discarded. The precipitate was resuspended in diethyl ether anhydrous and centrifuged again. This step was repeated, and then the washed precipitate was air dried in a fume hood for 5 min.

Precipitated peptides were re-dissolved in a loading buffer containing 20% Acetonitrile and 1% acetic acid in water, loaded and purified by semi-preparative chromatography in 0.1% TFA with an acetonitrile gradient (see Note 9) on a C18 RP HPLC column.

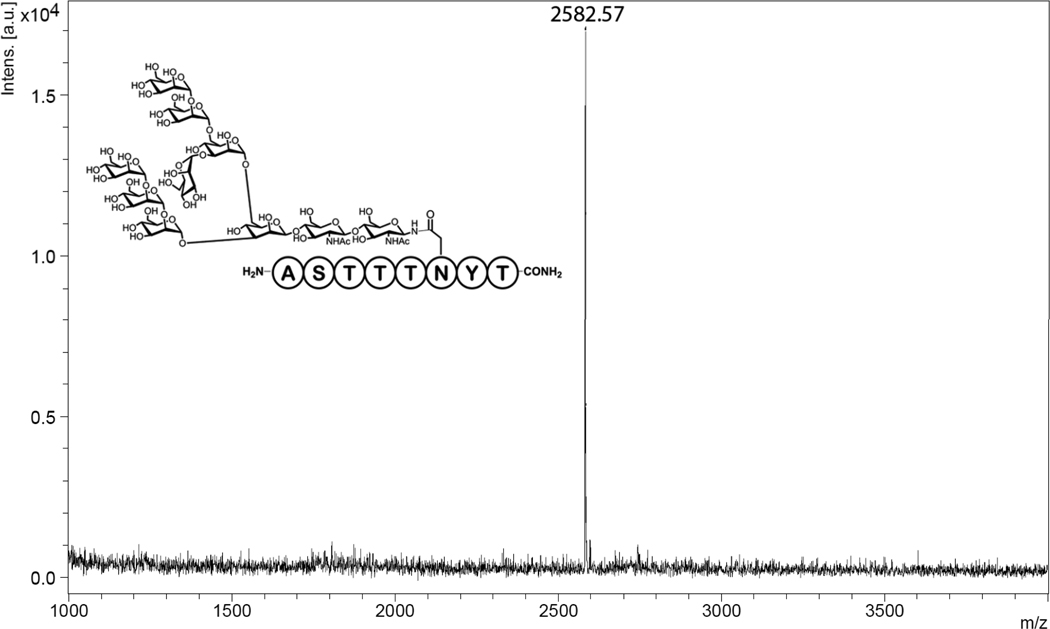

Preparative HPLC fractions were analyzed by analytical HPLC and MALDI-TOF MS to confirm their purity and peptide masses (see Fig. 4).

Purified glycopeptides were lyophilized and stored at −4°C.

Fig. 4.

MALDI-TOF-MS for the glycopeptide Man8GlcNAc2-Peptide T, expected mass: [M+Na]+=2582.97;

3.6. Recovery of unreacted high mannose oligosaccharide

One of the important benefits of this on-resin glycosylamine coupling approach is the possibility of convenient recovery of valuable, unreacted oligosaccharides after glycosylation reactions. By collecting the reaction solution after the glycosylation reaction described in 3.4 by filtration, precipitation, and silica gel purification some of the valuable N-linked oligosaccharides can be recovered.

The pooled reaction solutions from step 4 of 3.4 of the on-resin glycosylamine coupling reaction containing unused oligosaccharide in DMSO were precipitated with anhydrous diethyl ether.

The precipitate was then spun down by centrifugation and washed twice with diethyl ether.

The precipitate was then re-dissolved in minimum amount of an ethyl acetate/methanol/water (10:3:3) buffer, and then loaded onto an appropriately sized flash silica column (see Note 10).

The silica column was washed with an excess of ethyl acetate/methanol/ water buffer (10:3:3). Then, a gentle gradient of ethyl acetate/methanol/water (10:3:3 to 5:3:3) was performed and fractions were collected.

Phenol-sulfuric acid test was used to detect glycan containing fractions (see Note 11) (22), Positive fractions were pooled together and lyophilized to give Man8GlcNAc2, approximate yield 78% (based on the extra equivalents of Man8GlcNAc2 in the reactions).

Footnotes

The human-type Man8GlcNAc2 high mannose oligosaccharide was produced in a glycosylation deficient yeast strain (manuscripts in preparation).

PEGA resins are sold in wet form, preswelled in methanol. The mmole of resin was determined by the wet weight of the PEGA resin using the manufacturer’s reported substitution to convert weight to mmoles of substituted resin.

Ninhydrin test (21): First, the resin is washed consecutively with DMF (3 times) and dry DCM (3 times). A small amount of resin (an aliquot 20µL of resin in DCM) is transferred into a glass test tube. 30 µL of each Ninhydrin test solution (A, B, and C, see Materials 27) are added. The glass test tube is then placed in a heat block at 95°C for at least 5 min. Bluish color indicates incomplete reactions due to the detection of unreacted free amine.

In order to quantify the Fmoc removal, the 20% piperidine in DMF solutions need to be collected and pooled together. The loading can be determined by the equation: Loading (mmol/g) = (A/εl)×V/m, where A is the absorbance at 301 nm of the Fmoc removal solution (blanked by 20% piperidine in DMF); ε is 7800 cm−1M−1; l is the path length of the cuvette, 1 cm; V(ml) is the total volume of Fmoc removal solution; m (g) is the mass of the resin.

It is preferred to remove the PhiPr group immediately before step (4) on-resin glycosylamine coupling.

The Mini-spin columns need to be sealed carefully to prevent leaking of the reaction solutions and loss of valuable reagents.

By shortening the coupling time to 4 hours, we have observed slightly lower glycosylation yields. By extending the coupling reaction time to 24 hours, we have observed slightly better glycosylation yields.

The peptide’s N-terminal Fmoc was left on to aid quantification on analytical HPLC using 254 nm detection. The resulting crude, precipitated peptides were then analyzed by analytical HPLC (0–80% B, 10 min, Beckman SGB 0.46×5 cm Zorbax C8 column, A buffer: Water, 0.1% TFA; B buffer: 90% Acetonitrile 10% Water 0.1% TFA, detection at 254 nm). Individual peaks were identified by mass spectrometry and product distribution (glycopeptide: uncoupled peptide: aspartimide and its adduct) was determined by the integrated analytical HPLC absorption signal using Peaksimple 2000 version 2.83 (SRI Instruments). Glycosylation yields were calculated as the glycopeptide percentage in the crude.

The acetonitrile gradient varies depending on the different glycopeptides being purified. An analytical HPLC trial is recommended to be carried out prior to preparative HPLC purification to guide development of the purification procedure.

The amount of silica gel used is 10 to 100 fold more than the crude sample by weight. The gradient needs to be gentle to allow better separation of product oligosaccharide from impurities. Usually Man8GlcNAc2 did not elute until the gradient polarity was increased to (5:3:3) ethyl acetate/methanol/water.

Phenol-sulfuric acid test (22): 20 µL sample, 1 µL phenol, and 50 µL concentrated sulfuric acid were added sequentially and mixed thoroughly. A yellow-orange color indicates the presence of glycan. If the color changes are very subtle, incubation at 37°C can help to facilitate the color development.

References

- 1.Chen R, Tolbert TJ. Study of On-resin Convergent Synthesis of N-linked Glycopeptides Containing a Large High Mannose Oligosaccharide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ja9104073. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pert CB, Hill JM, Ruff MR, Berman RM, Robey WG, Arthur LO, Ruscetti FW, Farrar WL. Octapeptides deduced from the neuropeptide receptor-like pattern of antigen T4 in brain potently inhibit human immunodeficiency virus receptor binding and T-cell infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9254–9258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Ursi A, Caliendo G, Perissutti E, Santagada V, Severino B, Albrizio S, Bifulco G, Spisani S, Temussi PA. Conformation-activity relationship of peptide T and new pseudocyclic hexapeptide analogs. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:413–421. doi: 10.1002/psc.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dove A. The bittersweet promise of glycobiology. Nature Biotech. 2001;19:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Exploiting the defensive sugars of HIV-1 for drug and vaccine design. Nature. 2007;446:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JC, Greenberg WA, Wong CH. Programmable reactivity-based one-pot oligosaccharide synthesis. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3143–3152. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lis H, Sharon N. Soybean agglutinin--a plant glycoprotein. Structure of the carboxydrate unit. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3468–3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudkin VY, Miller JS, Danishefsky SJ. Chemical synthesis of normal and transformed PSA glycopeptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:736–738. doi: 10.1021/ja037988s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demchenko AV. Strategic approach to the chemical synthesis of oligosaccharides. Letters in Organic Chemistry. 2005;2:580–589. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen R, Pawlicki MA, Hamilton BS, Tolbert TJ. Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of a hybrid N-linked oligosaccharide using N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I. Adv. Synth. & Catal. 2008;350:1689–1695. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeberger PH. Automated oligosaccharide synthesis. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:19–28. doi: 10.1039/b511197h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kan C, Trzupek JD, Wu B, Wan Q, Chen G, Tan Z, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. Toward Homogeneous Erythropoietin: Chemical Synthesis of the Ala(1)-Gly(28) Glycopeptide Domain by "Alanine" Ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja808707w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan Z, Shang S, Halkina T, Yuan Y, Danishefsky SJ. Toward Homogeneous Erythropoietin: Non-NCL-Based Chemical Synthesis of the Gln(78)-Arg(166) Glycopeptide Domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009 doi: 10.1021/ja808704m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hojo H, Nakahara Y. Recent progress in the field of glycopeptide synthesis. Biopolymers. 2007;88:308–324. doi: 10.1002/bip.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen-Anisfeld ST, Lansbury PT. A practical, convergent method for glycopeptide synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10531–10537. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandal M, Dudkin VY, Geng XD, Danishefsky S. In pursuit of carbohydrate-based HIV vaccines, Part 1: The total synthesis of hybrid-type gp120 fragments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004;43:2557–2561. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue CW, Thierry J, Potier P. 2-Phenyl Isopropyl Esters as Carboxyl Terminus Protecting Groups in the Fast Synthesis of Peptide-Fragments. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kates SA, Delatorre BG, Eritja R, Albericio F. Solid-Phase N-Glycopeptide Synthesis Using Allyl Side-Chain Protected Fmoc-Amino Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1033–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offer J, Quibell M, Johnson T. On-resin solid-phase synthesis of asparagine N-linked glycopeptides: Use of N-(2-acetoxy-4-methoxybenzyl) (AcHmb) aspartyl amide-bond protection to prevent unwanted aspartimide formation. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1996;1:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Packman LC. N-2 Hydroxy-4-Methoxybenzyl (Hmb) Backbone Protection Strategy Prevents Double Aspartimide Formation in a Difficult Peptide Sequence. Tetrahedron Letters. 1995;36:7523–7526. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser E, Colescot Rl, Bossinge Cd, Cook PI. Color Test for Detection of Free Terminal Amino Groups in Solid-Phase Synthesis of Peptides. Anal Biochem. 1970;34:595–598. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Likhosherstov LM, Novikova OS, Derevitskaja VA, Kochetkov NK. A New Simple Synthesis of Amino Sugar Beta-D-Glycosylamines. Carbohydrate Research. 1986;146:C1–C5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay C, Lorthioir OE, Parr NJ, Congreve M, McKeown SC, Scicinski JJ, Ley SV. Solid-phase reaction monitoring - Chemical derivatization and off-bead analysis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2000;71:110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]