Abstract

ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels play important roles in the regulation of membrane excitability in many cell types. ATP inhibits channel activity by binding to a specific site formed by the N and C termini of the pore-forming subunit, Kir6.2, but the structural changes associated with this interaction remain unclear. Here, we use fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to study the ATP-dependent interaction between the N and C termini of Kir6.2 using a construct bearing fused cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins (ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP). When expressed in human embryonic kidney cells, ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 channels displayed FRET that was augmented by agonist stimulation and diminished by metabolic poisoning. Addition of ATP to permeabilized cells or isolated plasma membrane sheets increased FRET. FRET changes were abolished by Kir6.2 mutations that altered ATP-dependent channel closure and channel gating. In the wild-type channel, the ATP concentrations, which increased FRET (EC50 = 1.36 mM), were significantly higher than those causing channel inhibition (IC50 = 0.29 mM). Demonstrating the existence of intermolecular interactions, a dimeric construct comprising two molecules of Kir6.2 linked head-to-tail (ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP) displayed less FRET than the monomer in the absence of nucleotide but still exhibited ATP-dependent FRET increases (EC50 = 1.52 mM) and channel inhibition. We conclude that binding of ATP to Kir6.2, (i) alters the interaction between the N- and C-terminal domains, (ii) probably involves both intrasubunit and intersubunit interactions, (iii) reflects ligand binding not channel gating, and (iv) occurs in intact cells when subplasmalemmal [ATP] changes in the millimolar range.

Keywords: ATP-sensitive potassium channel

Potassium channels that are ATP-sensitive (KATP) couple intermediary metabolism to cellular electrical activity and thereby play important roles in the regulation of insulin secretion (1), cardiac excitability (2), and neuronal activity (3). In pancreatic β cells, KATP channels are responsible for the membrane depolarization produced by elevated glucose concentrations (4). This depolarization leads to Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and thus to insulin release (5). Transgenic mice expressing β-cell KATP channels with reduced ATP sensitivity develop severe hyperglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, and ketoacidosis (6), whereas knockout of the KATP channel poreforming subunit, Kir6.2, in mice eliminates the first phase of glucose-induced insulin secretion (7).

Kir6.2 possesses two transmembrane domains, with the N and C termini lying intracellularly (Fig. 1Ai). Previous studies have demonstrated that purified peptides derived from the N and C termini bind to each other in vitro (8, 9). The crystal structures of bacterial Kir channel, KirBac1.1, and the eukaryotic channel Kir3.1 indicate that the cytosolic domains interact within the intact channel and suggest that equivalent residues may fulfill this role in Kir6.2 (10). In Kir6.2, the putative interaction domains include residues responsible for regulation by ATP (11–14), protons (15), and phospholipids (16). However, there has been no direct demonstration that ATP can modulate the interaction between the N and C termini of Kir6.2, either in vitro or in intact cells.

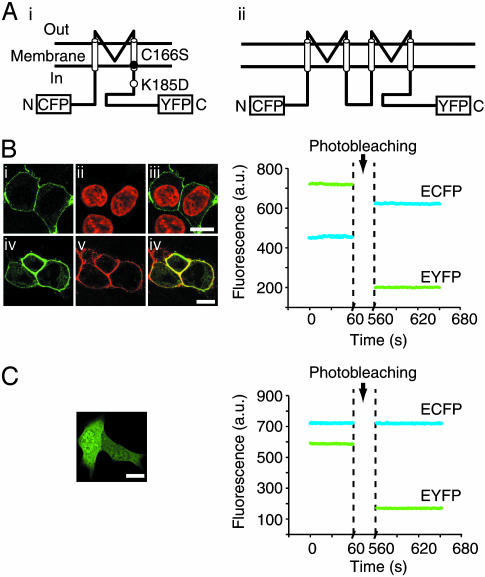

Fig. 1.

ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP displays FRET. (A) Topology of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP (i) and ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP (ii) (dimer) channel constructs. The location of mutated residues is indicated. (B Left)(i) Confocal image of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 fluorescence in HEK cells, visualized by illumination with 440-nm light. (ii) Nuclei of the same cells stained with Hoechst 34580 and visualized by illumination with 405-nm light. (iii) Overlay of i and ii.(iv) Confocal image of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 fluorescence. (v) Image of FM4–46-stained plasma membrane fluorescence, visualized by illumination with 532-nm light, in the same cell. (vi) Overlay of iv and v. (Bars = 10 μm.) (Right) Changes in the fluorescence intensity of EYFP (yellow line) and ECFP (cyan line) before and after photobleaching. Cells expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 were illuminated with 440-nm light and photobleached by 515-nm light for 500 s. (C Left) Confocal image of HEK cells expressing ECFP and EYFP (as separate proteins, observed by illumination with 440-nm light). (C Right) Fluorescence intensity of EYFP (yellow line) and ECFP (cyan line) before and after photobleaching. Cells expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 were illuminated with 440-nm light and photobleached by 515-nm light for 500 s.

In this study, we use fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to explore the interaction between the N and C termini of Kir6.2. The spectral properties of enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and yellow fluorescent proteins (EYFP) are well suited for measurements of molecular rearrangements by this technique (17). We therefore fused cDNAs to generate Kir6.2 bearing ECFP and EYFP at the cytoplasmic N and C termini, respectively (ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP; Fig. 1 Ai) (18). Labeled channels were expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, and ATP-dependent rearrangements of the cytosolic domains of Kir6.2 were monitored via changes in FRET in intact or permeabilized cells and in membrane sheets. Our results reveal that the distal N and C termini of Kir6.2 lie in close proximity and change their relative conformation in response to changes in ATP concentration.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Biology. The ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP construct has been described (18) and contains a silent mutation at base 192 of Kir6.2 that introduces a unique SalI site and a second AccI site. To generate plasmids containing Kir6.2 mutations, the 516-bp AccI fragment from ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP was replaced with that containing either Kir6.2C166S or Kir6.2K185D. The 1.2-kbp SalI fragment from a plasmid containing a Kir6.2-Kir6.2 dimer, constructed using overlap extension PCR by S. Tucker (Oxford, U.K.), was introduced into the SalI site of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP to generate ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP. The linker sequence between the two Kir6.2 domains encodes GQQGNQQNQAG.

Cell Culture. HEK cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland), 3 mM glucose, and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were plated on poly l-lysine-coated glass coverslips and transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmids encoding ECFP or EYFP (Clontech) or with 0.2 μg of the plasmid containing the indicated Kir6.2 FRET construct and 0.8 μg of pcDNA3 containing rat SUR1 (GenBank accession no. L40624), by using LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen) or FuGENE 6 (Roche Biochemicals) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Cells were used 2–4 days after transfection.

FRET Imaging. Cells were imaged in modified Krebs–Hepes bicarbonate (KB) or intracellular buffer (IB) (see below) at 37°C by using an Olympus IX-70 (Melville, NY) microscope fitted with a monochromator (Polychrome IV, TILL Photonics, Grafelfing, Germany) and an IMAGO charge-coupled device camera (TILL Photonics) controlled by tillvision software (TILL Photonics). For FRET measurements, a 455DRLP dichroic mirror (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, NY) and two emission filters [(D485/40 for ECFP and D535/30 for EYFP (Chroma)] alternated by a filter changer (Lambda 10–2, Sutter Instruments, San Rafael, CA) were used. Images were acquired at 1 Hz during constant illumination at 440 nm.

KB medium comprised (in mM) 132.5 NaCl, 3.6 KCl, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 0.5 MgSO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 2 NaHCO3, and 0 glucose and was then preequilibrated with 95:5 O2:CO2, pH 7.4. IB comprised (in mM) 5 NaCl, 140 K-gluconate, 7 MgSO4, 2 MgCl2, 20 Hepes, and 0 glucose and was then preequilibrated with 95:5 O2:CO2, pH 7.4. Cells were permeabilized by incubation in IB medium containing digitonin (10 μM) for 2 min at 37°C and subsequently maintained in IB solution. Isolated plasma membrane sheets (“roofless” cells) (19), attached to the coverslip, were prepared by sonication in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2/120 mM potassium glutamate/20 mM potassium acetate/2 mM EGTA/0.5 mM DTT at 0–4°C and incubation at room temperature for 10 min before imaging.

Visualization of Nucleus and Plasma Membrane. Nuclear staining was performed with 5 μg/ml Hoechst 34580 (Molecular Probes) in KB medium for 30 min and plasma membrane staining with 16 μM FM4-46 (Molecular Probes; 2 min in KB medium). Cells were imaged on a Leica TCS-AOBS laser-scanning confocal microscope (×63 PL-Apo 1.4 numerical aperture oil immersion objective).

Measurement of [ATP]c and [ATP]m with Recombinant Luciferases. Free cytoplasmic ([ATP]c) and mitochondrial ([ATP]m) ATP concentration were measured after cell infection with adenoviruses expressing cytosolic (cytLuc) or mitochondrially targeted (mitLuc) luciferase (20–22), respectively, by photon-counting imaging as described previously (21).

Electrophysiological Measurements. Currents were recorded by using an EPC-7 (List-Medical, Darmstadt, Germany) patch–clamp amplifier, a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), and pclamp8 software (Axon) at room temperature (20–24°C). Patch pipettes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (Harvard Apparatus, Edenbridge, U.K.), coated with Sylgard (Dow-Corning), and heat-polished. The effects of metabolic inhibition on KATP currents were studied by using the perforated-patch technique 1–4 days after transfection. Cells were identified by exciting EYFP by using a GFP epifluorescence filter set (Nikon). The pipette solution contained 65 mM K2SO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2). Amphotericin B (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO at 60 mg/ml and diluted in the pipette solution to a final concentration of 0.24 mg/ml. The bath solution contained 137 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 2.6 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). After perforation (>30 ns), cells were held at –70 mV and alternate ± 10-mV pulses of 500-ms duration were applied at a frequency of 0.5 Hz. Currents were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 1 kHz.

ATP and ADP sensitivities of recombinant KATP channels were measured in inside-out patches. The pipette (extracellular) solution contained (in mM) 50 K2SO4, 40 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 10 Hepes (pH 7.4). The bath (intracellular) solution was IB plus K2ATP or K2ADP (Sigma), as indicated. The Mg-free solution comprised IB buffer in which Mg salts were replaced by 10 mM EGTA. Excised patches were held at 0 mV, and 3-s-long voltage ramps from –110 to +100 mV were applied. Currents were low-pass filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 133 Hz.

All experiments (fluorescence and electrophysiology) were performed in the presence of Mg2+ ions, unless otherwise indicated.

Data Analysis and Statistics. Electrophysiological data were analyzed by using clampfit 8.2 (Axon) and origin 5. Whole-cell conductance was measured between –80 and –60 mV, and the conductance of excised patches was measured between –100 and +20 mV. The Hill equation was fit to the relationship between ATP concentration and KATP conductance (G), measured relative to that in ATP-free solution (GC),

|

[1] |

where IC50 is the concentration of ATP that produces a 50% reduction in conductance and h is the Hill coefficient. ATP-dependent changes in FRET were measured by fitting the Hill equation to the relationship between [ATP] and the fluorescence ratio.

Data are given as mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments. Comparisons between means were performed by using one-tailed Student's t test with excel (Microsoft) or origin 7 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) software.

Results and Discussion

Monitoring FRET Within ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 Channels. We first compared the fluorescence ratio (530 ± 15 nm vs. 485 ± 20 nm) in intact HEK cells expressing either unattached ECFP plus EYFP or Kir6.2 labeled with ECFP at the N terminus and EYFP at the C terminus (ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP) (Fig. 1 Ai) (18). SUR1 was coexpressed with ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP, which ensured correct targeting of >90% of Kir6.2 to the plasma membrane (23) (Fig. 1B Left). The resting fluorescence ratios of the ECFP/EYFP and ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 couples were 0.82 ± 0.12 (n = 5) and 1.53 ± 0.26 (n = 10, P < 0.05 from ECFP/EYFP), respectively. To confirm that the higher fluorescence ratio of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP resulted from FRET, we photobleached the acceptor EYFP using high-intensity light at 515 nm for 500 s. As expected, this maneuver significantly increased the fluorescence from ECFP in parallel with a decrease in EYFP fluorescence (Fig. 1B Right) but had no effect on ECFP fluorescence from cells expressing ECFP and EYFP as separate proteins (Fig. 1C Right).

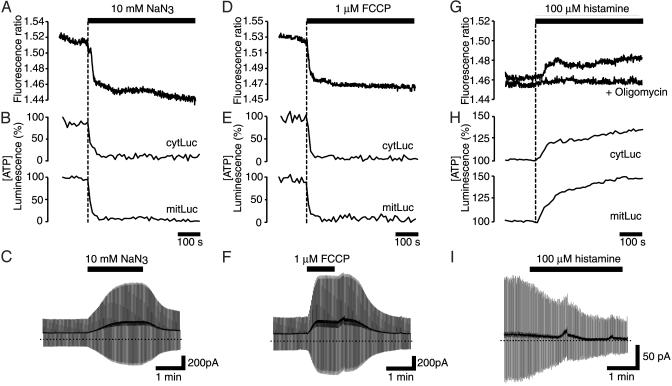

Effect of Changes in Intracellular-Free [ATP] on FRET Within ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP in Living Cells. We next examined the effects of changing intracellular [ATP] on the interaction between the intracellular domains of Kir6.2 by using azide (10 mM) or carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 μM) to inhibit mitochondrial ATP synthesis. Whereas neither inhibitor had any effect on the fluorescence of unattached ECFP or EYFP (data not shown), the fluorescence ratio of the ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 couple was rapidly reduced by either agent (Fig. 2 A and D) in parallel with decreases in free [ATP] in the cytosol ([ATP]c) and mitochondria ([ATP]m) (Fig. 2 B and E). Thus, [ATP]c fell to 8.2 ± 3% (n = 5) or 9.6 ± 2% (n = 5), and [ATP]m to 7.6 ± 4% (n = 5) or 8.6 ± 4% (n = 5), of the prestimulatory value in response to azide (Fig. 2B) or FCCP (Fig. 2E), respectively. Correspondingly, when whole-cell currents were recorded from cells coexpressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP and SUR1, using the perforated patch configuration to preserve intracellular metabolism, azide (Fig. 2C) or FCCP (Fig. 2F) increased the membrane conductance by 124 ± 38% and 128 ± 44% (n = 5), respectively. The whole-cell current was inhibited by the sulfonylurea tolbutamide (200 μM, data not shown), indicating that it flowed through KATP channels. Taken together, these data suggest that a fall in [ATP]c is associated with activation of the KATP channel and a decrease in the extent of FRET between the N (ECFP) and C (EYFP) termini of Kir6.2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of metabolic inhibitors and histamine on ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1. Effects of azide (10 mM, Left), carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (1 μM, Center), and histamine (100 μM, Right) or histamine plus oligomycin (5 μM) on the FRET signal (A, D, and G), [ATP]c and [ATP]m (B, E, and H), and whole-cell KATP currents (C, F, and I). (A, D, and G) Typical traces recorded from three different cells are shown (P < 0.05 from basal in each case). Similar results were observed in four other cells. (B, E, and H) Averaged traces recorded from five different cells are shown. (C, F, and I) Whole-cell currents recorded in response to ±10-mV pulses from –70 mV from a cell expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1. The dotted lines indicate the zero current level, and the solid lines indicate the time of application of the agent. Current responses were measured at steady state (C and F) or after 2 min of histamine application (I).

Agonist-induced increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) elevate both [ATP]c and [ATP]m in fibroblasts (24). To determine whether such [ATP]c increases enhance the ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 FRET signal, we perifused HEK cells with histamine (100 μM), a Gq-coupled receptor agonist that leads to the generation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ (24). Pyruvate (0.1 mM) and lactate (1.0 mM) were added to the perifused cells to increase the contribution of mitochondrial ATP synthesis to cellular ATP production. Histamine provoked a rise in [ATP]c (peak value: 134 ± 11%, n = 5) and [ATP]m (peak value: 148 ± 24%, n = 5) (Fig. 2H). This was matched by a marked increase in the FRET signal from ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (Fig. 2G) and a decrease in membrane conductance of 43 ± 7% (n = 6) (Fig. 2I). The FRET change was prevented by pretreatment with 5 μM oligomycin, a mitochondrial F1F0 ATPase inhibitor (Fig. 2G, +oligomycin), which did not affect [Ca2+] changes (not shown). This implicates enhanced ATP synthesis, rather than phospholipid breakdown, as causing the FRET change.

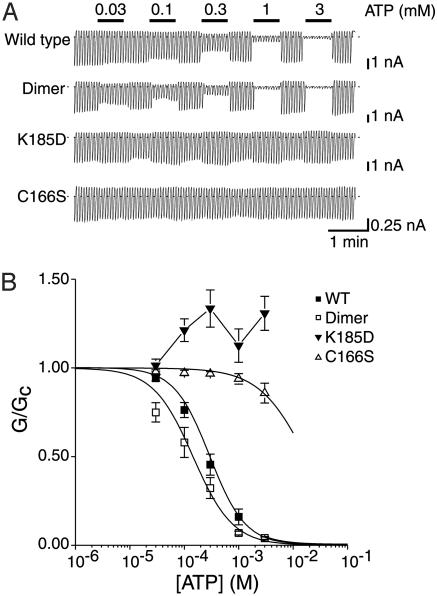

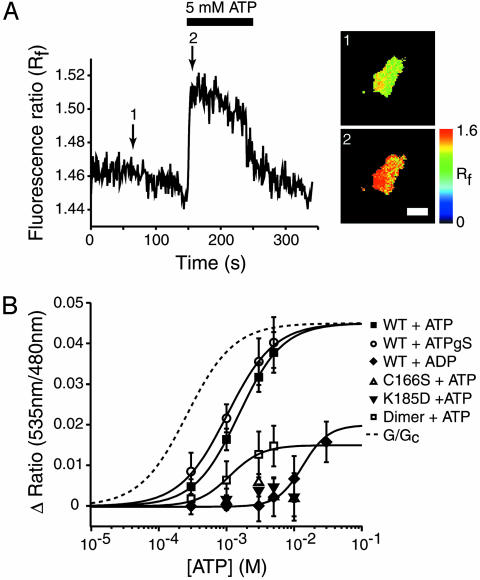

Effect of Added ATP and ADP on FRET in Isolated Membranes and Permeabilized Cells. Application of ATP (5 mM) to digitoninpermeabilized HEK cells expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 markedly increased the FRET signal. The relationship between [ATP] and the increase in the fluorescence ratio was half-maximal (EC50) at 1.78 ± 0.4 mM (n = 5). This value is much higher than the IC50 observed for ATP inhibition of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 channels (Fig. 3A), which was 0.29 ± 0.07 mM (n = 7) (Fig. 3B). The Hill coefficients (h) were 1.31 ± 0.23 for the FRET signal and 1.33 ± 0.04 for current inhibition.

Fig. 3.

ATP sensitivity of KATP channels formed by coexpression of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP and SUR1. (A) KATP current recorded in response to repetitive voltage ramps from –110 to +100 mV in an inside-out patch excised from an HEK cell expressing SUR1 and either ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP or the dimeric or mutant FRET constructs indicated. The dotted line indicates the zero current level. ATP (0.003–3 mM) was applied to the intracellular membrane face as indicated. (B) Mean relationship between [ATP] and KATP conductance (G), expressed relative to the conductance in the absence of nucleotide (Gc) for ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (WT, ▪), ECFP-Kir6.2C166S-EYFP/SUR1 (C166S, ▵), ECFP-Kir6.2K185D-EYFP/SUR1 (K185, ▾), or ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (dimer, □). n = 5–7 patches in each case. For WT and dimer, the solid line is the best fit of the Hill equation to the data (see text). For C166S and K185D, the lines are drawn through the points by eye.

To exclude the possibilities that (i) the ATP concentration at the plasma membrane of the permeabilized cells might not reflect that in the bath solution and (ii) signals might be affected by the presence of a small number of KATP channels on contaminating intracellular membranes, we measured FRET by ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 in isolated membrane sheets (see Materials and Methods). Addition of ATP (5 mM) to the intracellular membrane surface increased FRET (Fig. 4A). With half-maximal activation at 1.36 ± 0.4 mM ATP (h = 1.41 ± 0.32, n = 5; Fig. 4B, ▪), a value not significantly different from those obtained in digitonin-permeabilized cells (P = 0.135). Application of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analogue ATPγS (5 mM) also increased FRET in isolated membrane sheets (Fig. 4B, ○) with a similar EC50 (1.02 ± 0.12 mM; h = 1.24 ± 0.06; n = 5). FRET was also increased by ADP, although the latter was much less effective than ATP, and the concentration–response curve did not fully saturate even at 30 mM ADP (Fig. 4B, ♦). We measured the relative inhibitory effects of ATP and ADP on KATP currents in the absence of Mg2+ to avoid the stimulatory effects of Mg nucleotides mediated by SUR1 (25). Consistent with the lower sensitivity of the FRET signal to ADP, the IC50 for channel inhibition was 182 ± 18 μM (n = 4) for ADP and 38 ± 1 μM (n = 5) for ATP (Hill coefficients 1.3 ± 0.3 and 2 ± 0.2, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ATP on FRET efficiency of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 in membrane sheets. (A Left) Representative recording of the change in the fluorescence ratio in a membrane sheet prepared from a HEK cell expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1. ATP (5 mM) was applied as indicated. (Right) The FRET level at the time points (1 and 2) indicated on the trace. The vertical scale bar indicates the fluorescence ratio in pseudocolor, and the horizontal line indicates 5 μm. (B) Relationship between ATP, ADP, or ATPγS concentration and the increase in the fluorescence ratio in cells expressing ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (▪), ECFP-Kir6.2C166S-EYFP/SUR1 (▵), ECFP-Kir6.2K185D-EYFP/SUR1 (▾), or ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (□). The solid line is the best fit of the Hill equation to the data (see text). The fit for ADP was estimated by fixing the maximal FRET increase and gave an EC50 of 13.36 ± 0.67 mM; h = 2.31 ± 0.24 (n = 5). The dashed line shows the relationship between ATP and KATP conductance based on Fig. 3B.

The IC50 for ATP inhibition of ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 currents in excised patches (0.29 mM) was about 10-fold higher than that of the unlabeled channel in both presence and absence of Mg2+ (25), indicating that the presence of the fluorescent proteins disrupts inhibition by ATP. This effect may be mediated by the N-terminal tag because attachment of GFP to the C terminus of Kir6.2 does not alter the channel ATP sensitivity (26), whereas attachment of SUR1 to the N terminus of Kir6.2 lowers the ATP sensitivity (27).

Nucleotides can interact with both Kir6.2 and SUR subunits (1). To confirm that the increase in FRET we observed results from binding of ATP to Kir6.2 and not to SUR1, we used two ATP-insensitive mutants of Kir6.2 (K185D and C166S). Mutation of the lysine residue at 185 to aspartic acid abolishes ATP inhibition of KATP currents (14). This effect was retained when the FRET construct carrying the Kir6.2K185D mutation was cotransfected with SUR1 into HEK cells (Fig. 3B); indeed, ATP now activated the KATP current (via its interaction with SUR1; ref. 25). No change in FRET was observed on application of ATP to isolated membranes (Fig. 4B, ▾).

The Kir6.2C166S mutation reduces the ability of ATP to block the KATP channel and also induces a marked increase in the channel open probability (Po) (28). It is possible to account for the reduced ATP sensitivity of this channel simply by the effect on Po (28). However, when ECFP-Kir6.2C166S-EYFP and SUR1 were coexpressed in HEK cells, ATP had little effect on either the KATP current (Fig. 3B) or on the associated FRET signal (Fig. 4B, ▵). This suggests that ATP binding to Kir6.2 is also reduced by the C166S mutation. Furthermore, we observed no difference in the resting fluorescence ratio of the wild-type channel and either the K185D (1.31 ± 0.12, n = 7) or C166S (1.29 ± 0.11, n = 7) mutants measured in membrane sheets in the absence of ATP. When measured in intact cells, the resting fluorescence ratio of the wild-type channel (1.53 ± 0.26, n = 10) was significantly higher than that of either the K185D (1.34 ± 0.14, n = 10; P < 0.05) or C166S (1.31 ± 0.18; n = 10; P < 0.05) mutants, consistent with the fact that only the wild-type construct was affected by the presence of intracellular ATP.

The C166S mutation causes a marked reduction in the long closed state of the channel (28) but does not obviously alter the FRET signal. Furthermore, we observed increases in the FRET signal with concentrations of ATP higher than those required to close the channel pore. Taken together, these data indicate that FRET does not monitor the opening and closing of the channel. Instead, we monitor a conformational change consequent on ATP binding that involves the N and C termini of Kir6.2.

Intrasubunit vs. Intersubunit Interactions. We next examined whether the interaction between the N- and C-terminal fluorescent tags occurs between or within subunits of the Kir6.2 tetramer by using a dimeric construct ECFP-Kir6.2-Kir6.2-EYFP (Fig. 1 Aii) to reflect interactions between separate subunits. Coexpression of this construct with SUR1 generated KATP currents with slightly higher ATP sensitivity than ECFP-Kir6.2-EYFP/SUR1 (Fig. 3A; IC50 for ATP = 0.15 ± 0.04 mM, h = 1.19 ± 0.1, n = 5 for the dimer and 0.29 ± 0.07 mM, n = 7 for the monomer; Fig. 3B). The resting FRET signal was also significantly smaller for the dimer than the monomer (1.12 ± 0.11 vs. 1.53 ± 0.26, n = 10, P < 0.05), suggesting that a component of the fluorescence signal reported by the latter is derived from intrasubunit FRET. However, the fluorescence ratio of the dimer was increased by ATP with a similar potency (EC50 = 1.52 ± 0.23 mM, h = 1.34 ± 0.02, n = 4; Fig. 4B, □). The complex FRET/distance relationship prevents us from drawing any inferences from the reduced magnitude of the ATP-dependent FRET. However, the lack of a change in the ATP sensitivity argues that ATP binding involves a change in the relationship between the N terminus of one subunit and the adjacent C terminus of another.

A rotation and decrease in the distance between the N and C termini of adjacent subunits has been reported for the related G protein-coupled channel GIRK/Kir3.x on stimulation (29); in this case, however, ligand binding leads to opening of the pore rather than closing. Our data are consistent with the view that the N and C termini of Kir6.2 move closer together when ATP binds, but we cannot exclude the possibility that ATP causes rotation of the termini.

The crystal structure of the intracellular domains of Kir3.1 reveals that the N and C termini interact (10), and that of KirBac1.1 (30) further shows that this interaction occurs between the N terminus of one subunit and the C terminus of the adjacent subunit. It therefore seems possible that the ATP-binding site of Kir6.2 may involve the N and C termini of adjacent subunits. Although neither structure is complete, the data suggest that in both Kir3.1 and KirBac1.1, FRET could occur between the N and C terminus of both the same and an adjacent subunit (assuming an R0 value on the order of 50 Å for this FRET pair). This may explain why the resting fluorescence ratio is smaller for the dimeric Kir6.2 construct than the monomer (note that the fluorescence ratio is independent of the number of FRET couples).

Comparison of ATP Sensitivity of the KATP Current and FRET Signal. The IC50 for KATP channel inhibition (0.29 mM) was ≈5-fold greater than the EC50 of the FRET signal (1.4 mM). A similar discrepancy was also observed previously for channel inhibition and radiolabeled nucleotide binding using ATP-[γ]4-azidoanilide (31). This difference might reflect the fact that, although there are four ATP-binding sites in the tetrameric channel, binding of only a single ATP is sufficient to close the pore (32). Alternatively, the ATP-binding sites may show negative cooperativity, such that after the first ATP has bound and shut the channel, further ATP molecules bind with reduced affinity, thus producing a lower EC50 for FRET. Finally, although both the FRET signal and channel closure induced by ATP must result from a conformational change in the protein, the coupling between these two events and ATP binding may not be identical.

Several pieces of evidence support the idea that the FRET change results from ATP binding rather than channel closure. First, the C166S mutation markedly alters channel gating (in the absence of ATP) but did not affect resting FRET. Second, there is a marked difference in the ATP sensitivity of the FRET change and of channel inhibition. Third, ATP (Fig. 4A) and tolbutamide (18) exert opposite effects on FRET, although each causes channel closure. Thus, the FRET construct described here may provide a useful tool to measure ATP binding to Kir6.2 and to distinguish the effects of mutations on nucleotide binding and channel gating.

Conclusion

We provide here independent confirmation that ATP binds directly to Kir6.2 (9, 33) and show that the physical association between the cytoplasmic N and C termini of Kir6.2 (9) is modulated in an ATP-dependent manner. These findings are consistent with studies showing that mutations in both the N and C terminus influence the ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2 (11–14, 34, 35).

It has long been recognized that the ATP sensitivity of the KATP channel measured in excised patches does not reflect that found in the intact cell, which is shifted to higher ATP concentrations by the presence of MgADP and lipids such as PIP2 and long-chain acyl CoAs (36). In contrast, FRET detects a conformational change consequent on ATP binding to Kir6.2, with little interference from ADP, and thus is a more reliable indicator of submembrane ATP levels. The dynamic range of the concentration–response relation for the FRET change, measured in excised patches, was 200 μM to 5 mM ATP. TheFRET change evoked in intact cells by metabolic poisoning is of similar magnitude, suggesting that metabolic poisoning must produce an equivalent change in submembrane [ATP], and consistent with resting ATP levels in this domain at or above 1 mM (37–39). Thus, the ATP-dependent changes in Kir6.2 conformation reported should provide a useful new optical approach to monitor changes in subplasmalemmal ATP concentration dynamically in living cells.

Acknowledgments

J.D.L. holds an Edward Penley Abraham Cephalosporin Fellowship at Linacre College, F.M.A. is the Royal Society GlaxoSmithKline Research Professor, and G.A.R. is a Wellcome Trust Research Leave Fellow. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust Program Grant 067081/Z/02/Z (to G.A.R.), the Royal Society, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Human Frontiers Science Program, the Medical Research Council (U.K.), and Diabetes U.K.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: HEK, human embryonic kidney; [ATP]c, free cytosolic ATP; [ATP]m, free mitochondrial ATP; KATP, ATP-sensitive K+ channel; Kir6.2, inwardly rectifying K+ channel; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; ECFP, enhanced cyan fluorescent protein; EYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; IB, intracellular buffer.

References

- 1.Ashcroft, F. M. & Gribble, F. M. (1998) Trends Neurosci. 21, 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazdunski, M. (1994) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 24, Suppl. 4, S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada, K., Ji, J. J., Yuan, H., Miki, T., Sato, S., Horimoto, N., Shimizu, T., Seino, S. & Inagaki, N. (2001) Science 292, 1543–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashcroft, F. M., Harrison, D. E. & Ashcroft, S. J. (1984) Nature 312, 446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter, G. A. (2001) Mol. Aspects Med. 22, 247–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster, J. C., Marshall, B. A., Ensor, N., Corbett, J. A. & Nichols, C. G. (2000) Cell 100, 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seino, S., Iwanaga, T., Nagashima, K. & Miki, T. (2000) Diabetes 49, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu, Z., Yang, Z., Cui, N., Zhu, G., Liu, C., Xu, H., Chanchevalap, S., Shen, W., Wu, J., Li, Y., et al. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31573–31580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tucker, S. J. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33393–33397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida, M. & MacKinnon, R. (2002) Cell 111, 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.John, S. A., Weiss, J. N., Xie, L. H. & Ribalet, B. (2003) J. Physiol. 552, 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koster, J. C., Sha, Q., Shyng, S. & Nichols, C. G. (1999) J. Physiol. 515, 19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, L., Wang, J. & Drain, P. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 841–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker, S. J., Gribble, F. M., Proks, P., Trapp, S., Ryder, T. J., Haug, T., Reimann, F. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 3290–3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu, H., Wu, J., Cui, N., Abdulkadir, L., Wang, R., Mao, J., Giwa, L. R., Chanchevalap, S. & Jiang, C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38690–38696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shyng, S. L., Cukras, C. A., Harwood, J. & Nichols, C. G. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 116, 599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsien, R. Y. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippiat, J. D., Albinson, S. L. & Ashcroft, F. M. (2002) Diabetes 51, Suppl. 3, S377–S380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holroyd, P., Lang, T., Wenzel, D., De Camilli, P. & Jahn, R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16806–16811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ainscow, E. K., Zhao, C. & Rutter, G. A. (2000) Diabetes 49, 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainscow, E. K. & Rutter, G. A. (2001) Biochem. J. 353, 175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuboi, T., Da Silva Xavier, G., Holz, G. G., Jouaville, L. S., Thomas, A. P. & Rutter, G. A. (2003) Biochem. J. 369, 287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zerangue, N., Schwappach, B., Jan, Y. N. & Jan, L. Y. (1999) Neuron 22, 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jouaville, L. S., Pinton, P., Bastianutto, C., Rutter, G. A. & Rizzuto, R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13807–13812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gribble, F. M., Tucker, S. J., Haug, T. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7185–7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John, S. A., Monck, J. R., Weiss, J. N. & Ribalet, B. (1998) J. Physiol. 510, 333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shyng, S. & Nichols, C. G. (1997) J. Gen. Physiol. 110, 655–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trapp, S., Proks, P., Tucker, S. J. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1998) J. Gen. Physiol. 112, 333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riven, I., Kalmanzon, E., Segev, L. & Reuveny, E. (2003) Neuron 38, 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo, A., Gulbis, J. M., Antcliff, J. F., Rahman, T., Lowe, E. D., Zimmer, J., Cuthbertson, J., Ashcroft, F. M., Ezaki, T. & Doyle, D. A. (2003) Science 300, 1922–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanabe, K., Tucker, S. J., Ashcroft, F. M., Proks, P., Kioka, N., Amachi, T. & Ueda, K. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272, 316–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markworth, E., Schwanstecher, C. & Schwanstecher, M. (2000) Diabetes 49, 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker, S. J., Gribble, F. M., Zhao, C., Trapp, S. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1997) Nature 387, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proks, P., Gribble, F. M., Adhikari, R., Tucker, S. J. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1999) J. Physiol. 514, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reimann, F., Ryder, T. J., Tucker, S. J. & Ashcroft, F. M. (1999) J. Physiol. 520, 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashcroft, F. M. & Gribble, F. M. (1999) Diabetologia 42, 903–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ainscow, E. K., Mirshamsi, S., Tang, T., Ashford, M. L. & Rutter, G. A. (2002) J. Physiol. 544, 429–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gribble, F. M., Loussouarn, G., Tucker, S. J., Zhao, C., Nichols, C. G. & Ashcroft, F. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30046–30049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kennedy, H. J., Pouli, A. E., Ainscow, E. K., Jouaville, L. S., Rizzuto, R. & Rutter, G. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13281–13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]