Abstract

Kinetic analysis of guanine alkylation by aflatoxin B1 exo-8,9-epoxide, the reactive form of the hepatocarcinogen aflatoxin B1, reveals the reaction to be > 2000-times more efficient in DNA than in aqueous solution, i.e. with free 2’-deoxyguanosine. Thermodynamic analysis reveals AFB1 exo-8,9-epoxide intercalation as the predominant source of the observed DNA catalytic effect. However, the known exo > endo epoxide stereospecificity of the DNA alkylation is observed even with free deoxyguanosine (ratio > 20:1 determined by LC-MS and NMR measurements), as predicted by theoretical calculations (Bren, U. et al. Chem Res. Toxciol. 20, 1134–1140, 2007).

Introduction

Many carcinogens are transformed by enzymes to electrophiles that react with DNA (1). Because the resulting DNA lesions can cause replication blockage and particularly miscoding events leading to mutations, this process has been of considerable interest in cancer research (2). The short-lived nature of the reactive forms of activated carcinogens has made the study of their chemistry and kinetics technically difficult, as well as their selectivity with individual DNA residues (3). One of the factors of interest is the rate acceleration of conjugation of an activated carcinogen due to the DNA environment. Although some of these electrophilic chemicals have been reacted with nucleosides and nucleoside triphosphates, rates have not been measured (e.g., polycyclic hydrocarbon diol epoxides) (4). Alternatively, the kinetics of reactions of sulfonate esters of aryl hydroxamic acids have been measured with dGuo (5) but apparently not DNA.

The natural product aflatoxin B1 (AFB1)1 is one of the most potent hepatocarcinogens known and constitutes a major public health issue in several areas of the world (6). All of the genotoxic activity of AFB1 can be understood in terms of AFB1 8,9-epoxide, which is formed by P450 enzymes (7). The exo stereoisomer reacts with DNA ≥ 103 faster than the endo isomer and therefore only the exo form is genotoxic (8). Although the intercalation of AFB1 into DNA represents an established part of the mechanism of reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide (8, 9), the reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with free dGuo has also been reported (10), but its reaction rate constant was never determined. On the other hand, the kinetics of reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with DNA have been analyzed in detail (11). In this study, the reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with dGuo in aqueous solution was characterized accordingly.

Experimental Procedures

Caution! AFB1 is a known hepatocarcinogen and must be handled with appropriate precautions. Wear disposable nitrile gloves and destroy all samples in bleach

Reagents

Dry acetone was prepared by treatment with anhydrous K2CO3 and distillation from P2O5 (12). AFB1 8,9-epoxide was prepared by oxidation of AFB1 with dimethyldioxirane (13). All work with AFB1 was done in amber glass because of the light sensitivity. The fractions of exo and endo isomers (plus any AFB1 dihydrodiol) were determined by NMR in CDCl3. Dilutions of AFB1 8,9-epoxide were made in dry acetone. The concentrations of AFB1 8,9-epoxide were estimated by addition of aliquots to 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) to form AFB1-diol, which was quantified by UV measurements (ε360 21,800 M−1 cm−1).

Reaction of AFB1 8,9-Epoxide with dGuo

Stock solutions of dGuo (20 mM) were prepared in 5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) by sonication with a microtip (Branson Digital Soniter, Branson, Danbury, CT), using 70% maximum amplitude. (The dGuo did not change the pH.) Ten µL of 4.5 mM AFB1 8,9-epoxide was added to 0.50 mL of 5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing varying concentrations of dGuo, mixed immediately with a vortex device (at 25 °C) (duplicate experiments). After 5 min, 75 µL of 1 M HCl was added and the samples were heated at 80 °C for 30 min to cleave the glycosidic bond. Insoluble material was precipitated by centrifugation (10 min, 3 × 103 × g). Aliquots (50 µL) were injected onto an octadecylsilane (C18) HPLC column (3 µm, 6.2 mm × 80 mm, Zorbax, MacMod, Chadds Ford, PA). A linear gradient of 25 to 75% CH3OH, v/v (in 20 mM NH4CH3CO2, pH 4.5) over 20 min (flow 2.0 mL min−1) was used. The effluent was monitored using a UV3000 HR system (ThermoElectron, Piscataway, NJ) in the rapid scanning monochromator mode, with quantitation based on A360 measurements. The identity of the AFB1-Gua peak was confirmed in a separate LC-MS analysis: [M+H]+ m/z 480.1, confirmed by HRMS, 480.1159, calc. mass 480.1155, C22H18N5O8. Calibration was based on an external standard prepared from treatment of calf thymus DNA treated in the same way, purified by HPLC, and quantified by UV (ε360 26,800 M−1 cm−1).

Liquid Chromatography

Reversed-phase HPLC purification was performed using a Beckman Coulter system comprised of a System Gold 126 solvent module and a 168 diode array detector; 32 Karat (v. 7.0, Beckmann Coulter, Fullerton, CA) software was used for the acquisition, processing, and analysis of HPLC data. The diode array detector was configured to monitor both 254 nm and 360 nm wavelengths. A Gemini (10 mm × 250 mm, 5 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) column was used at a flow rate of 2.0 mL min−1. Separation prior to MS analysis was conducted on a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA) with a binary solvent manager. A Gemini (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 µm, Phenomenex) column was used at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM NH4HCO2 buffer (pH 8.0) with a CH3CN gradient increasing from 20 to 40% (v/v) over 20 min.

Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Analysis was conducted ousing an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron, San Jose, CA) equipped with an Ion Max API electrospray source and a 50 mm inner diameter stainless steel capillary. The instrument was tuned and calibrated over a mass range of m/z 195 to 1822. An injection volume of 10 µL was used. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode.

Spectroscopy

UV measurements were recorded using a Cary 14-OLIS instrument (On-Line Instrument Systems, Bogart, GA). NMR experiments were performed at a 1H frequency of 600 MHz on a Bruker Avance II spectrometer with a 5 mm Z-gradient TCI Cryo-probe. AFB1 8,9-epoxide was dissolved in CDCl3. AFB1-Gua was dissolved in 99.9% D2O and referenced to residual H2O (δ 4.773 ppm at 25 ± 0.5 °C). Solvent signal suppression was achieved using the WET suppression technique (14, 15). Acquisition parameters were as follows: 32K complex data points, 2K scans per FID, sweep width 12020 Hz, relaxation delay 1.8 s. Carrier frequencies were set at 4.7 ppm for 1H and 170 ppm for 13C. TOPSPIN (v 2.0.b.6, Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used for data processing and analysis. Spectra were apodized with a Gaussian function and baseline corrected with a 5th degree polynomial.

Calculations

Gnuplot version 4.2 was used for fitting of Equation 1 to the experimental adduct yields over the entire dGuo concentration range and provided the best estimate for knon, 12.6 M−1 s−1. Fitting of Equation 2 to the linear portion of the experimental adduct yields ([dGuo] <10 mM) gave the best estimate for knon, a value of 11.9 M−1 s−1.

Results and Discussion

Quantitation of AFB1 8,9-Epoxide Reaction with dGuo

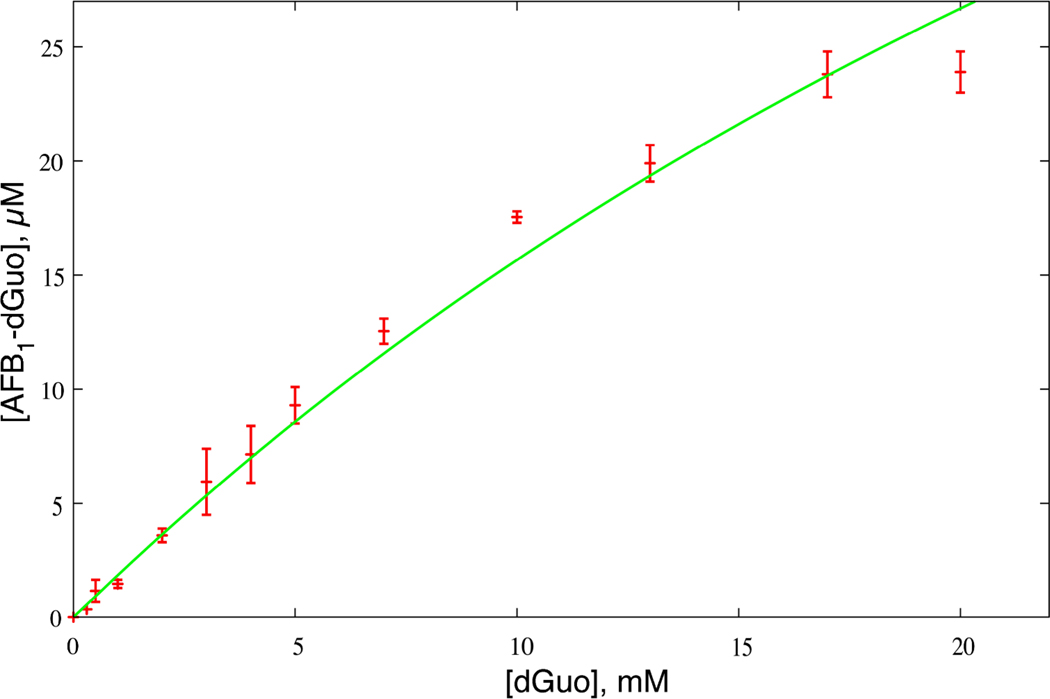

Varying concentrations of dGuo were reacted with (90 µM) AFB1 8,9-epoxide (96% exo, 4% endo) and the yield of 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-deoxyguanosyl)-9-hydroxy AFB1 (AFB1-dGuo) adduct was determined (as 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-guanyl)-9-hydroxy AFB1 (AFB1-Gua)) by HPLC-UV measurements (Figure 1). The yield increased with the dGuo concentration.

Figure 1.

Formation of AFB1-dGuo adduct as a function of dGuo concentration. Error-bars depict experimental adduct yields and line represents kinetic model of Equation 1 using a knon value of 12.6 M−1 s−1.

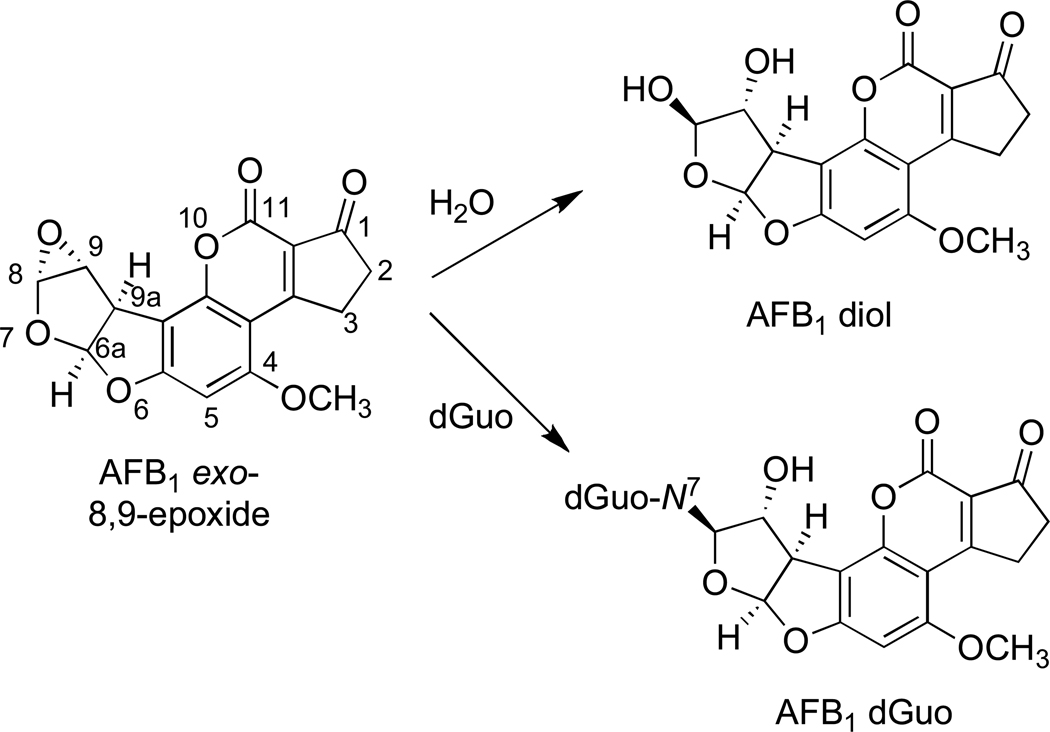

The formation of the AFB1-dGuo adduct is competitive with AFB1 8,9-epoxide (AFB1-O) hydrolysis (Scheme 1) giving rise to the 8,9-dihydrodiol (AFB1-diol)

The corresponding rate equation for AFB1 8,9-epoxide is

where [ ] indicates molar concentration and ka and knon represent second-order rate constants. Hydrolysis can be treated as a pseudo-first-order reaction with the corresponding rate constant ka’ = ka[H2O] of 0.6 s−1 (16). Because only ~ 0.1% of the dGuo reacts, its concentration can be considered constant and the adduct formation as a pseudo-first-order reaction as well. In the case of two competing (pseudo) first-order reactions the quotient of their (pseudo) first-order rate constants equals the quotient of the amounts of their respective products

This expression, in combination with the mass balance for the added 90 µM concentration of AFB1 8,9-epoxide,

provides the final relation after simple rearrangement

| (1) |

At low dGuo concentrations where knon[dGuo] ≪ ka’, the model gives a linear relationship

| (2) |

At higher dGuo concentrations the knon[dGuo] term begins to contribute and the observed yield begins to plateau (Figure 1).

Scheme 1.

Competing reactions of AFB1 exo-8,9-epoxide with dGuo and H2O.

Stereoselectivity of Reaction of AFB1 8,9-Epoxide with dGuo

The separation of the exo and endo isomers of AFB1 8,9-epoxide by fractional crystallization is possible (8, 17, 18) but not trivial, and even the best endo AFB1 8,9-epoxide preparations have some exo contamination. We used an alternate strategy to address the stereochemistry of the reaction. An AFB1 8,9-epoxide preparation, determined to contain 7.7% endo epoxide (Figure S1, Supporting Information), was reacted with dGuo (20 mM) under the same conditions used in the analytical procedure (vide supra) and the product was analyzed.

One possibility is that a putative endo-derived (diasteromeric) AFB1-Gua adduct might separate during chromatography, e.g. as in the case of the GSH conjugates (18). LC-MS analysis showed only one HPLC peak with the correct UV (A360, A260) and m/z characteristics, i.e. major fragmentation between guanine and AFB1 moities, m/z 329 and m/z 152 (19) (Figure S2, Supporting Information).

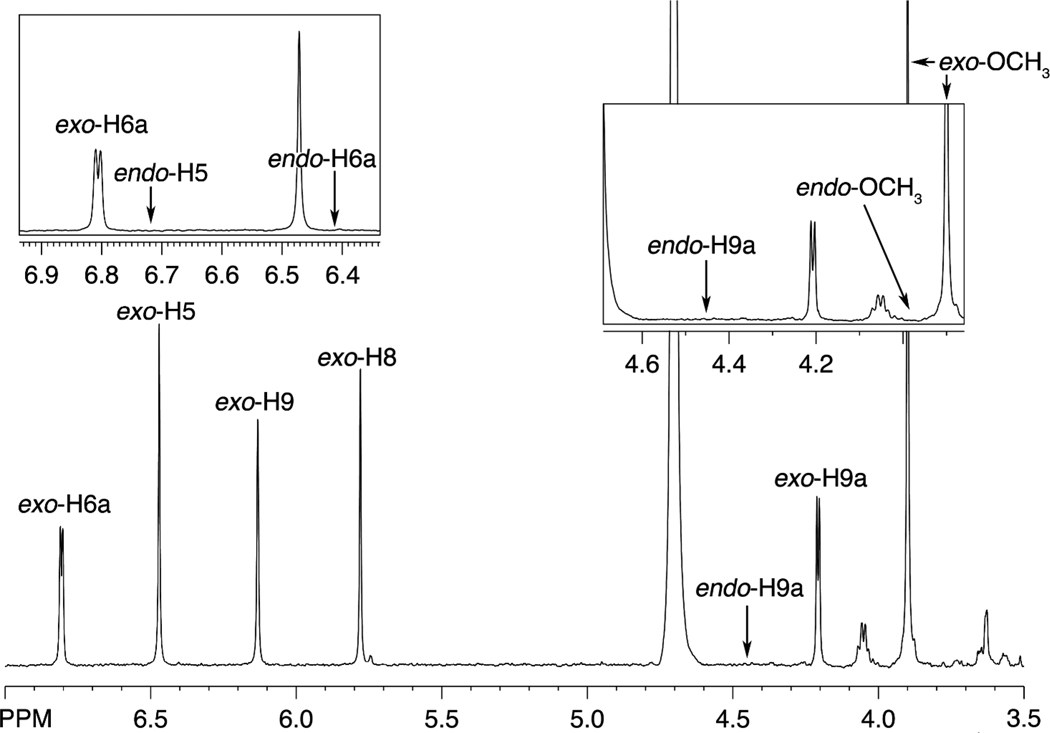

The AFB1-Gua adduct was isolated and analyzed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy (Figure 2), with all signals corresponding to the exo isomer in the literature (19). In the absence of an authentic endo adduct, the chemical shifts are uncertain but can be predicted from the behavior of the diastereomeric GSH conjugates and should be similar to those (± 0.5 ppm) (17, 18). Intra-residue proton coupling was predicted to be identical to those previously reported. There were no observed peak patterns congruent to predicted chemical shifts or coupling patterns. The limit of detection of an endo product was < 0.35% based on the singlets and < 0.65% based on doublets, with the former limit considered a better estimate. These values can be compared with the 7.7% endo isomer in the AFB1 8,9-epoxide used in the reaction. Thus the exo isomer of AFB1 8,9-epoxide is > 20-fold more reactive with free dGuo than the endo.

Figure 2.

1H-NMR spectrum of isolated AFB1-Gua adduct. The shift assignments (19) and expected shift values of an endo product are shown. Expansions are in the boxes.

Analysis of Activation Barriers

The reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with dGuo can now be compared directly with the DNA alkylation. The dGuo reaction is best described by a relationship (vide supra) that predicts saturation at higher dGuo concentrations. The reaction has a second-order rate constant knon of 12 M−1 s−1 (Figure 1), which can be connected to the non-catalyzed activation free energy (ΔG≠non) of 16.2 kcal mol−1 using transition state theory

| (3) |

where kB, T, and h represent the Boltzmann constant, thermodynamic temperature, and Planck constant, respectively. An analogous expression relates the DNA alkylation rate constant kcat, experimentally determined to be in the range of 35 to 42 s−1 (11), to the corresponding activation free energy (ΔG≠cat) of 15.4 to 15.5 kcal mol−1. Dissociation constants (Kd) for the preceding intercalation have been determined in the range of 0.27 to 1.45 mM, depending on different experimental techniques and nucleobase sequences used (10, 11), and can be related to the binding free energy (ΔGbind) of −4.9 to −3.9 kcal mol−1 via a standard thermodynamic expression

| (4) |

The catalytic efficiency for guanine alkylation in DNA, kcat/Kd, represents a second-order rate constant which can be expressed, using Equations 3 and 4, as

| (5) |

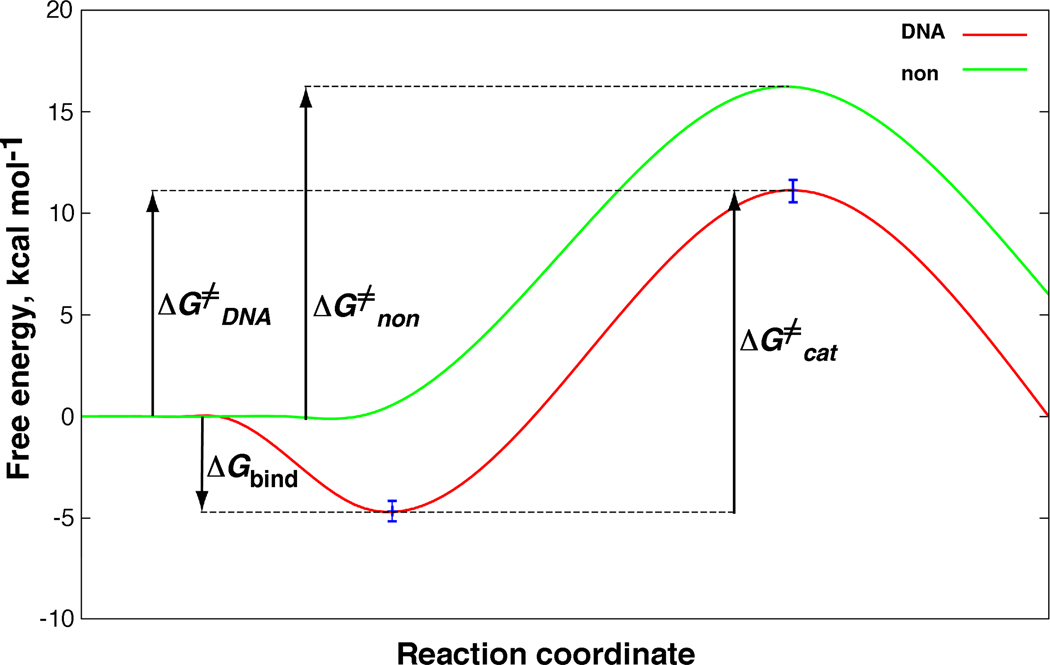

and related to the DNA activation free energy (ΔG≠DNA) of 10.5 to 11.6 kcal mol−1. Comparison with ΔG≠non gives a DNA catalysis value between 4.6 and 5.7 kcal mol−1 (Figure 3). These results represent average DNA values and it is known that some sequences within the genome will have higher affinities and reactivity and some will have lower (10, 20, 21).

Figure 3.

Schematic free-energy profiles for guanine alkylation by AFB1 exo-8,9-epoxide in DNA (red) and in aqueous solution (green). For details and definition of symbols see Equations 3 to 5.

Conclusions

In contrast to enzymes, DNA is not optimized to catalyze its reaction with AFB1 8,9-epoxide. The logic can be considered reversed—it is the aflatoxin which was optimized to utilize the DNA asymmetric environment in order to enhance its reactivity, presumably providing protection to the molds that synthesize this toxin. Its large planar body facilitates DNA intercalation, which contributes the most to the observed catalytic effect (3.9 to 4.9 kcal mol−1). However, the chemical step is catalyzed as well, by 0.7 to 0.8 kcal mol−1. There are two possible explanations: (i) absence of an entropic solvent cage effect (22) due to formation of a DNA-aflatoxin complex, or (ii) preorganized electrostatics (23) of the DNA microenvironment which could stabilize the zwitterionic intermediate formed during DNA alkylation, because its positive charge is buried in the negatively charged DNA while its negative charge is exposed to the cation-rich microenvironment of DNA (11).

In conclusion, guanine alkylation by AFB1 exo-8,9-epoxide is (based on the conservative estimate of DNA catalysis of 4.6 kcal mol−1) > 2000-times more efficient in DNA than with the free nucleoside in aqueous solution (Figure 3). Thermodynamic analysis reveals AFB1 exo-8,9-epoxide intercalation as the predominant source (85%) of the observed DNA catalytic effect with subsequent chemical step contributing the remaining 15%. Reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with dGuo shows an inherent stereospecificity of the exo > endo isomer (> 20-fold), as (although at a somewhat lower magnitude of 0.5 kcal mol−1) predicted by our ab initio calculations (24). This preference (for exo > endo) is further magnified in the reaction with DNA due to AFB1 8,9-epoxide intercalation (8, 10). This study represents a successful application of enzymatic kinetics to treatment of DNA alkylation, yet another piece in the mosaic of the elusive nature of these important bio-macromolecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. G. Chowdhury for discussion of the LC-MS results and Dr. J. Mavri for careful reading of the manuscript. Financial support from the NIH (USPHS R01 ES010546, R01 CA055678, and P30 ES000267), the Slovenian Ministry of Science and Higher Education (P1-0012), and a World Federation of Scientists scholarship (U. B.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFB1, aflatoxin B1; AFB1-dGuo, 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-deoxyguanosyl)-9-hydroxy AFB1; AFB1-Gua, 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-guanyl)-9-hydroxy AFB1. The abbreviations for nucleosides and nucleic acid bases are standard for this journal.

Supporting Information Available: Figure S1, 1H-NMR analysis of fractions of exo and endo AFB1 8,9-epoxide. Figure S2, LC-MS of the products of the reaction of AFB1 8,9-epoxide with dGuo. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Searle CE. Chemical Carcinogens, Vol. 1 and 2. Washington, D.C: Amer. Chem. Soc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhury G, Guengerich FP. Direct detection and mapping of sites of base modification in DNA fragments by tandem mass spectrometry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:381–384. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vepachedu SR, Ya N, Yagi H, Sayer JM, Jerina DM. Marked differences in base selectivity between DNA and the free nucleotides upon adduct formation from bay- and fjord-region diol epoxides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:883–890. doi: 10.1021/tx000073w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak M, Kennedy SA. Selective trapping of N-acetyl-N-(4-biphenyl)nitrenium and N-acetyl-N-(2-fluorenyl)nitrenium ions by 2'-deoxyguanosine in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:574–575. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busby WF, Wogan GN. Aflatoxins. In: Searle CE, editor. Chemical Carcinogens. Washington, D.C: Amer. Chem. Soc.; 1984. pp. 945–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Evidence for cytochrome P-450NF, the nifedipine oxidase, being the principal enzyme involved in the bioactivation of aflatoxins in human liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:462–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iyer R, Coles B, Raney KD, Thier R, Guengerich FP, Harris TM. DNA adduction by the potent carcinogen aflatoxin B1: mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1603–1609. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raney KD, Gopalakrishnan S, Byrd S, Stone MP, Harris TM. Alteration of the aflatoxin cyclopentenone ring to a δ-lactone reduces intercalation with DNA and decreases formation of guanine N7 adducts by aflatoxin epoxides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1990;3:254–261. doi: 10.1021/tx00015a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raney VM, Harris TM, Stone MP. DNA conformation mediates aflatoxin B1-DNA binding and the formation of guanine N7 adducts by aflatoxin B1 8,9-exo-epoxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1993;6:64–68. doi: 10.1021/tx00031a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson WW, Guengerich FP. Reaction of aflatoxin B1exo-8,9-epoxide with DNA: kinetic analysis of covalent binding and DNA-induced hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:6121–6125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiberg KB. Laboratory Technique in Organic Chemistry. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1960. p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baertschi SW, Raney KD, Stone MP, Harris TM. Preparation of the 8,9-epoxide of the mycotoxin aflatoxin B1: the ultimate carcinogenic species. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:7929–7931. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smallcombe SH, Patt SL, Keifer PA. WET solvent suppression and Its applications to LC NMR and high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. J. Magnet. Resonance, Ser. A. 1995;117:295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogg RJ, Kingsley RB, Taylor JS. WET, a T1- and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in vivo localized 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Magnet. Resonance, Ser. B. 1994;104:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson WW, Harris TM, Guengerich FP. Kinetics and mechanism of hydrolysis of aflatoxin B1exo-8,9-oxide and rearrangement of the dihydrodiol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8213–8220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raney KD, Coles B, Guengerich FP, Harris TM. The endo 8,9-epoxide of aflatoxin B1: a new metabolite. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992;5:333–335. doi: 10.1021/tx00027a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raney KD, Meyer DJ, Ketterer B, Harris TM, Guengerich FP. Glutathione conjugation of aflatoxin B1exo and endo epoxides by rat and human glutathione S-transferases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992;5:470–478. doi: 10.1021/tx00028a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essigmann JM, Croy RG, Nadzan AM, Busby WF, Jr, Reinhold VN, Büchi G, Wogan GN. Structural identification of the major DNA adduct formed by aflatoxin B1in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1977;74:1870–1874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.5.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mariën K, Moyer R, Loveland P, van Holde K, Bailey G. Comparative binding and sequence interaction specificities of aflatoxin B1, aflatoxicol, aflatoxin M1, and aflatoxicol M1 with purified DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:7455–7462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopalakrishnan S, Harris TM, Stone MP. Intercalation of aflatoxin B1 in two oligodeoxynucleotide adducts: comparative 1H NMR analysis of d(ATCAFBGAT) d(ATCGAT) and d(ATAFBGCAT)2. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10438–10448. doi: 10.1021/bi00498a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. New York: Dover Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warshel A, Florian J. Computer simulations of enzyme catalysis: finding out what has been optimized by evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:5950–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bren U, Guengerich FP, Marvi J. Guanine alkylation by the potent carcinogen aflatoxin B1: quantum-chemical calculation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:1134–1140. doi: 10.1021/tx700073d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.