Abstract

Background

The spider Cupiennius salei (Keyserling 1877) has become an important study organism in evolutionary and developmental biology. However, the available staging system for its embryonic development is difficult to apply to modern studies, with strong bias towards the earliest developmental stages. Furthermore, important embryonic events are poorly understood. We address these problems, providing a new description of the embryonic development of C. salei. The paper also discusses various observations that will improve our understanding of spider development.

Results

Conspicuous developmental events were used to define numbered stages 1 to 21. Stages 1 to 9 follow the existing staging system for the spider Achaearanea tepidariorum, and stages 10 to 21 provide a high-resolution description of later development. Live-embryo imaging shows cell movements during the earliest formation of embryonic tissue in C. salei. The imaging procedure also elucidates the encircling border between the cell-dense embryo hemisphere and the hemisphere with much lower cell density (a structure termed 'equator' in earlier studies). This border results from subsurface migration of primordial mesendodermal cells from their invagination site at the blastopore. Furthermore, our detailed successive sequence shows: 1) early differentiation of the precheliceral neuroectoderm; 2) the morphogenetic process of inversion and 3) initial invaginations of the opisthosomal epithelium for the respiratory system.

Conclusions

Our improved staging system of development in C. salei development should be of considerable value to future comparative studies of animal development. A dense germ disc is not evident during development in C. salei, but we show that the gastrulation process is similar to that in spider species that do have a dense germ disc. In the opisthosoma, the order of appearance of precursor epithelial invaginations provides evidence for the non-homology of the tracheal and book lung respiratory systems.

Background

The field of research aiming to clarify the evolution of development and the relationship between developmental changes and phenotypic evolution is called evolutionary developmental biology (or 'evo-devo'). A common evo-devo strategy is to compare the development of so-called model organisms, which are often chosen because of their phylogenetic position. For example, based on gene expression data in spider embryos, it has been proposed that the parasegmental boundary is a conserved trait in arthropod development [1]. The argument was that spiders are part of a basally branching clade (chelicerates) within the euarthropods [2,3] and that shared traits between spiders and any other arthropods are thus likely to reflect the arthropod ancestral state [1]. Another reason to select a particular model species is for its ability to give new insights into a specific evolutionary developmental theme [4], such as the evolution of novelties. The many evolutionary adaptations specific to spiders make them particularly suitable for this research theme. Examples include the tubular trachea; the silk producing system; complex silk spinning behaviour and the remarkable optical system. All these features probably contributed to the success of spiders in occupying a broad range of terrestrial and even aquatic ecosystems. These diverse spider adaptations studied in a phylogenetic context may shed more light on their evolution as well as on the principles of adaptive evolution in general.

It is therefore very promising that two spider species, Cupiennius salei and Achaearanea tepidariorum have emerged over the years as experimental models for embryological studies [5]. C. salei, a wandering spider (Ctenidae), has been the subject of neurological, physiological and behavioural studies over many decades [e.g. [6-8]]. More recently, this species has also been used for evo-devo studies [e.g. [9-15]]. It is especially suitable for developmental studies because of easy maintenance and the high number of large eggs available throughout the year. Other benefits include the possibility of performing functional analyses of genes via embryonic RNAi, in-situ hybridisation in advanced developmental stages and the relative ease of dissection of its large embryos [16,17]. A. tepidariorum, a cobweb spider (Theridiidae) has also become very popular for evo-devo studies in recent years [5]. The advantages of this species include a short generation time, parental RNAi and in-situ hybridisation of the earliest stages. These features make A. tepidariorum a particularly suitable subject for the study of early development. Its ecology also differs significantly from that of C. salei. For example, A. tepidariorum captures prey by using silk [18,19], whereas C. salei does not use its silk for this purpose. The silk spinning organs, which relate to this difference in behaviour, differ in their morphology as well [5,20] and differentiate during late embryonic development. The two species thus complement one another as laboratory model organisms for the comparison of chelicerate embryology with those of other major arthropod taxa. These species also exhibit organ differences that may have been crucial in their evolution. Furthermore, molecular techniques available for both species permit detailed comparisons between them.

In order to facilitate cross-species comparisons in evo-devo studies, clear and comparable embryological staging systems are required. Such systems have proved indispensible for the study of other arthropods such as the insect Drosophila melanogaster [21,22] or the crustaceans Parhyale hawaiensis [23] and Porcellio scaber [24]. Unfortunately, comparably clear and comprehensive systems are not currently available for spider development. For A. tepidariorum, the early stages of development (until about the first appearance of the prosomal appendages) have recently been well defined [25]. Later embryonic and post-embryonic stages have not been defined for this species. A more complete staging system for C. salei does exist, covering the whole of its embryonic development [26] but this suffers from several flaws. First, this system is strongly biased towards early development and misses important aspects of late ontogeny. Second, it is based on embryonic timing (measured in hours after egg laying: hAEL). Timing is inappropriate for C. salei because of variations in the developmental rate of the eggs of different broods. Third, the images and drawings featured in that staging system are not detailed enough for comparison with modern imaging methods such as confocal scans [e.g. [27]]. This makes it difficult to draw comparisons between recent studies on organogenesis in C. salei, including those on heart development [28], brain development [27] and limb development [29]. It is even more difficult to draw comparisons between C. salei and other spider species.

A new morphological description of C. salei development is presented in this paper. Detailed pictures based on live-embryo imaging, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and fluorescent staining are also presented. In addition we look critically at the existing terminology for the first post-embryonic stages. The result is a series of 21 discrete embryonic stages that are linked cohesively to the first post-embryonic stages. All the stages can be easily identified via examination of living animals and by the use of common fluorescent markers on fixed specimens, thus providing a practical basis for future evo-devo studies.

Our observations have also allowed us to add new data to some long-standing morphological debates. One such problem area relates to gastrulation. Gastrulation is the morphogenetic process that separates an initially simple sheet of cells (the blastoderm) into the germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) thereby reorganizing the tissue with a greater degree of complexity. In spiders, gastrulation starts with the internalization of cells at the blastopore (or 'gastral groove' [30]). Gradually, a primary thickening (or primitive plate) is formed around the area of the blastopore [26,31]. With multiple cell layers underneath the blastoderm (now ectoderm) this area represents the mesendodermal mass (mesodermal and endodermal cells). In many spider species, the formation and subsequent differentiation of the blastopore takes place at the centre of a structure called a germ disc [31,32]. This is a regional differentiation of blastodermic cells that migrate together, aggregating in the form of a disc. Such germ discs, as seen for example in A. tepidariorum, exhibit a high cell density in relation to the extra-embryonic part of the egg [e.g. [5]]. The rim of the germ disc appears as a border circling the whole egg.

In C. salei, a dense germ disc is not formed [5,26]. In this species, before gastrulation the blastodermic cells in the embryonic portion of the egg do not appear to be denser than those of the extra-embryonic portion. Nevertheless, towards the end of gastrulation a visible border circling the whole egg appears between the embryonic and extra-embryonic regions. This border has been referred to in the past as the 'equator' [26]. The nature of the equator and the reason for this difference between C. salei and those species with a dense germ disc are poorly understood. In this publication, with the first live-embryo imaging data for C. salei, we offer an explanation for the appearance of the equator and compare our findings with conditions in species that do exhibit a dense germ disc.

Another complex aspect of spider embryonic development is the differentiation of the anterior-most part of the germ band. This part of the germ band consists of a precheliceral region, a cheliceral segment and a pedipalpal segment. The precheliceral region is composed of two large precheliceral lobes, with the anlage of the stomodeum (mouth opening) in between. These precheliceral lobes subdivide and later give rise to the protocerebrum, including the optic lobes. This subdivision comes about via the folding and packing of distinct areas into cerebral grooves (semi-lunar grooves) or vesicles.

Some putative relationships between the cerebral grooves and various other brain structures have been suggested for a number of spider species [33-37] and other arachnids [38,39]. For instance a recent SEM study on the grey widow spider Latrodectus geometricus, deals with the development of the precheliceral region [37] but the processes of migration and overgrowing of single brain compartments are not clearly documented. Another recent study on the development of the protocerebrum in C. salei demonstrated the major morphogenetic movements involved in the formation of the brain centres (including the optic centre, mushroom body and arcuate body). This study also included the expression of several genes that might play a role in this process [27]. However, the early developmental sequence of these movements is not described in fine detail.

In the present investigation, we show in detail the sequence of early differentiation of what will eventually become the individual brain parts from the precheliceral neuroectoderm of C. salei. This serves to complement and extend earlier studies of brain development in this species [27]. We show which areas of the precheliceral lobe the brain components are derived from, and clarify the separation of components from one another as development progresses.

In addition we describe three small 'pores' in the centre of the stomodeal anlage, similar to those observed in L. geometricus [37]. It is not currently understood what these pores are, but it has been proposed that their tri-radial construction may indicate a sister group relationship between pycnogonids (sea spiders) and chelicerates [40] and may therefore be of considerable phylogenetic value. The tools available for the study of C. salei will allow valuable future studies to increase understanding of this tri-radial structure.

We also include more detailed information about the later developmental processes of the embryo. For example, in parallel with the early differentiation of the brain parts, the germ band elongates by addition of more segments, and the whole embryo goes through a process of complex tissue movements known as inversion [30,41]. This process results in the enclosure of the dorsal yolk mass into the body of the embryo, and is accomplished by the dorsal migration of the right and left halves of the germ band that eventually meet in the dorsal midline (dorsal closure). To facilitate the precise mapping and description of developmental events during inversion, we divide the process into four stages (inversion I, II, III and dorsal closure).

Structures that undergo dramatic changes during inversion include the book lungs on the second opisthosomal segment and the tracheal system on the third opisthosomal segment, both of which are breathing organs. We observed fundamental differences in the sequence of appearance of the openings that give rise to the book lungs and the trachea, which we use to argue against the theory of serial homology of these organs [42].

Results

Embryonic stages

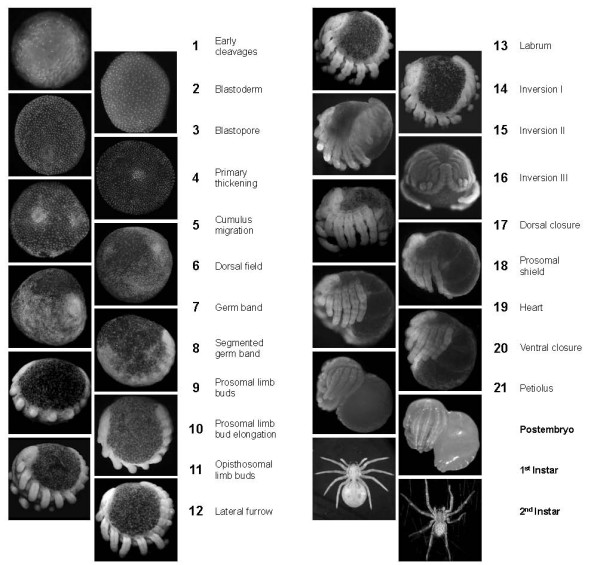

The numbered stages into which we divide development in C. salei are intended to replace the existing hAEL staging system by Seitz [26]. Besides a number, each stage is also given a colloquial name for practical use. Figure 1 gives a general overview of our new system, and additional file 1 provides a detailed comparison between the old and new systems. The number of stages allocated to early development (up to stage 6) is higher in the Seitz system, where the early stages are separated into numerous time (hour) intervals after egg laying (hAEL). The resolution we chose for the early stages reflects the degree of detail we were able to observe using our methods, and follows the staging nomenclature of A. tepidariorum [25] until stage 9 (prosomal limb buds). From stage 6 to 10, the staging resolution of the two systems is similar, and after stage 10 our new system is more detailed (additional file 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of development of the embryo, postembryo and first and second instar of C. salei. Nuclear stained embryos illustrate the 21 embryonic stages. The postembryo and the first and second instar are illustrated by images of live animals. Additional file 1 provides a comparison between this revised staging system and the system used in earlier publications.

Stage 1, Early cleavages

During the process of egg-laying, the female spider produces a liquid secretion that guides the soft and ovoid-shaped eggs from the genital opening into a silk pouch that is then formed by the female into a round cocoon [7]. The liquid secretion is absorbed by the eggs, which as a result increase in size, become more solid and take on a spherical shape of roughly 1.2 mm in diameter. During these first hours of development the eggs are sticky and fragile. Because of these conditions, we waited 12 to 24 hours before it was possible to remove intact single eggs for further investigation. Eggs at stage 1 largely consist of yolk, which is distributed as fine homogeneous granules. In these early stages, the nuclei are surrounded by a mass of yolk and not yet enclosed within cell membranes. The first cycles of nuclear division are superficial (nuclear mitosis without cytokinesis which results in a polynuclear cell). The divisions take place intralecithally in the centre of the egg (Figures 2a, b). Based upon earlier observations [26] we assume that the first cleavage cycles are synchronous. During these cleavages the nuclei start to migrate towards the egg surface. This migration results in an egg with an even distribution of nuclei (Figure 2c).

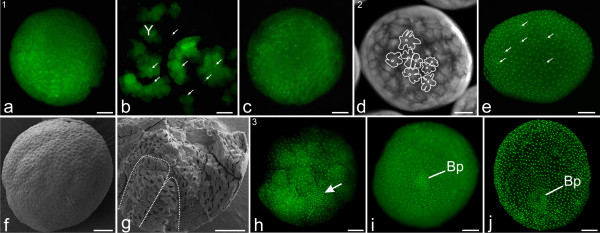

Figure 2.

Stages 1-3 of C. salei. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-c, e, h-j; light micrograph, d; SEMs, f, g. a-c, Stage 1, Early cleavages. a: The egg is spherical in shape, about 1.2 mm in diameter. Due to the large amount of yolk, the nuclei in the egg centre are not visible. b: Same egg as in a, broken apart. Nuclei (white arrows) are visible within the broken yolky mass (Y). c, More developed egg as in a with about 30 nuclei visible, still embedded in yolky mass. d-e, Stage 2, Blastoderm. d: In a live egg (egg number 2 from Additional file 2 at movie frame 76), the nuclei are visible as dark spots within the whitish periplasm. The periplasm is the primordial cytoplasm surrounding the nuclei and is lobate in shape (white lines) at the surface of the egg. e: Apart from some nuclei (white arrows) still surrounded by yolk only, most of the nuclei are enclosed by cell membranes, forming a cellular blastoderm. f: An egg (comparable to the egg in e) with a cellular blastoderm evident as a knobby surface texture. g: Parts of a broken egg at the same stage as the eggs in e and f. The yolky mass is now organized into large pyramid-shaped compartments (white dotted line). h-j, Stage 3, blastopore. h: A number of blastodermic cells aggregate and form the early blastopore (arrow). i: There are increasing numbers of cells in the blastopore (Bp) as it becomes more prominent. j: Slightly later, the blastopore (Bp) has a pore-like appearance.

Stage 2, Blastoderm

During stage 2, the cleavage energids (nuclei plus its surrounding cytoplasm) reach the egg surface where they are conspicuous with finger-like projections (Figure 2d, at movie frame 80 of Additional file 2). After a few division cycles, their cytoplasm attains a more rounded shape (at movie frame 210 of Additional file 2). This is when the cleavage type changes from superficial to holoblastic, and each nucleus on the egg surface is surrounded by its cell membrane (Figures 2e, f). A layer of early blastodermic cells is now evenly distributed over the egg surface (Figures 2e, f). The yolk mass is composed of compartments shaped like pyramids with the tips pointing towards the egg centre (white dotted line; Figure 2g). Data from nuclear staining and live-embryo imaging identify some nuclei that stay below the blastodermic cell layer (white arrows; Figure 2e). These nuclei probably belong to vitellophages; multi-nucleic cells which phagocytize the intracellular yolk. It is currently unclear whether all of these vitellophages have their origin in the early blastoderm (secondary immigration) or whether some of them derive from inside the egg [30,43]. However, it is likely that during cell migration from the egg centre to the surface, some cells remain in the yolk mass and do not reach the surface.

Stage 3, Blastopore

The following cell divisions are asynchronous. Because of the frequency of cell division cycles, the egg appears to contract (e.g. at movie frame 320 of Additional file 2). After roughly three cell division cycles, the contractions subside, leaving the blastodermic cells still more or less evenly distributed over the egg surface. There is no formation of a germ disc (a dense aggregation of cells that provides the primordial tissue for the embryo body and is commonly present in arthropod embryos [30]). However, in a particular region of the blastoderm cells begin aggregating to form the blastopore (white arrow; Figure 2h). Cells appear to migrate inwards at the blastopore (Figures 2h, i; at movie frame 200 of Additional file 3) and initiate gastrulation- the developmental process that results in a layer of mesendoderm beneath the surface layer of blastoderm (now ectoderm). As development progresses, the blastopore comprises more and more cells and becomes pore-like in appearance, while the surrounding blastoderm cells are no longer evenly distributed (Figure 2j).

Stage 4, Primary thickening

In the egg hemisphere that contains the advanced blastopore, scattered divisions result in an uneven distribution of the blastodermic cells. As a result, this half of the egg becomes more patchy (white arrows; Figure 3a). The blastodermic cells in the opposite egg hemisphere are evenly distributed though they appear to be fewer in number (Figure 3b). The blastopore region displays high nuclear density with the nuclei arranged in several layers. The pore-like composition of the blastopore disappears (Figure 3a). This indicates the end of gastrulation, i.e., the inward migration of cells at the blastopore. As development proceeds, the cellular tissue of the region where the blastopore formed becomes thicker and appears to bulge outwards (visible around movie frame 700 of Additional file 2). This conspicuous structure is known as the primary thickening, or cumulus anterior [25,31,32].

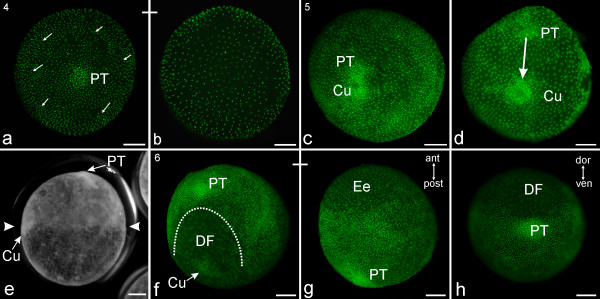

Figure 3.

Stages 4-6 of C. salei. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-d, f-g; light micrograph, e. a-b, Stage 4, Primary thickening. a: The blastopore region (evident in Figures 2h-j) consists of several dense layers of nuclei. It bulges slightly outwards, a phenomenon which in this and subsequent figures is called primary thickening (PT). The surrounding nuclei are arranged in irregular patches (arrows). b: Same egg as in a, seen from the opposite side. At this pole of the egg, the nuclei are more evenly distributed. c-e, Stage 5, Cumulus migrating. c: From the primary thickening, a large cell cluster (cumulus, Cu) starts to separate from the remaining rest of the primary thickening (PT). d: Due to the ongoing migration (white arrow) of the cumulus (Cu), the distance to the primary thickening (PT) increases. e: Living egg (egg number 1 from Additional file 2 at movie frame 960) in late stage 5. The cumulus (Cu) has reached its final position after separation from the primary thickening (PT). The migration of cells from the primary thickening beneath the surface layer has resulted in one hemisphere with greater cell density (top of photo e) compared with the other hemisphere (bottom of photo e). The line of demarcation between the dense hemisphere and the less dense one is the 'equator'. This marked difference in cell density is evident between the two arrowheads in e. f-h, Stage 6, Dorsal field. f: After the cumulus has reached the equator, it disintegrates. The tissue between the cumulus and the primary thickening spreads laterally, forming a region of low cell density called the dorsal field (DF). This region will continue to have much yolk in further stages of development. g: Same egg as in f rotated 120 degrees. The primary thickening (PT) is at the posterior edge of the developing embryo body and located in the hemisphere with greater cell density. The hemisphere with lower cell density is extra-embryonic (Ee) since it continues as a yolk-filled region. h: Posterior view of the primary thickening (PT). The dorsal field (DF) expands to about 100 degrees in width, and the cumulus has disappeared.

Stage 5, Cumulus migration

From the primary thickening (formerly the blastopore) clusters of internalised cells migrate in radial directions. Two different types of cellular movement are observed: The most prominent movement follows the asymmetrical fission of the primary thickening into two cell groups (visible in Additional file 2 at about movie frame 750 and in Additional file 3 at movie frame 570). A smaller group remains at the centre of the embryonic portion of the egg and continues to be identified as primary thickening. The larger cell group, the cumulus or cumulus posterior, is visible as a little bulge on the egg surface (Figures 3c-e; Additional files 2 and 3). The cumulus migrates about 90 degrees underneath the egg surface. The second type of cellular movement is a radial migration of single cells or groups of a few cells starting from the primary thickening. These cells (primordial mesendoderm) migrate directly underneath the ectodermal layer up to 90 degrees along the outer egg curvature (Additional files 2 and 3). At the end of the process, the migrating cells appear to be evenly distributed but are restricted to the egg hemisphere that has the primary thickening in its centre (Figure 3e).

The embryo now has two dissimilar egg hemispheres. The embryonic hemisphere appears to be more opaque because of the new layer of cells (primordial mesendoderm) underneath the ectoderm. The more translucent hemisphere is made up of extra-embryonic tissue, mainly filled with yolk in this and subsequent figures (e.g., Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6). The transition between the subsurface cell layer and the more translucent hemisphere has been called the 'equator' [26], and is clearly visible in living eggs (Figure 3e; Additional file 2). The cumulus is embedded at the edge of the equator and marks the anterior and dorsal region of the embryo body, while the primary thickening (in the centre of the embryonic hemisphere) is at the ventral and caudal pole of the embryo body (Figure 3e).

Figure 4.

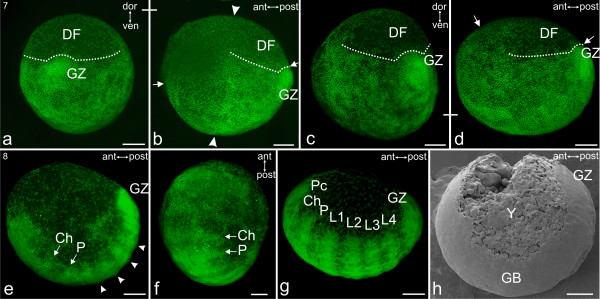

Stages 7 and 8 of C. salei. Sytox staining, a-g; SEM, h. All scale bars 200 μm. a-d, Stage 7, Germ band. a: Posterior view of the growth zone (GZ), a dense region that is continuous with the primary thickening (PT) in stage 6, Figure 3h. The dorsal field (DF) is extended to its maximum. b: Same egg as in a rotated by 90 degrees, such that the embryo is in lateral view. The embryonic tissue (early germ band) extends along the ventral curvature between the two arrows. Between the two white arrow heads is the equator, which is the sharp change in cell density that marks the border of migration of mesendodermal cells from the primary thickening. c: Postero-lateral view of an embryo that is slightly more developed than the one in a and b. d: Lateral view of the same embryo as shown in c. The embryonic tissue (early germ band) extends along the ventral curvature between the two white arrows. This region has more cells and a much higher density than the dorsal field (DF). The equator is no longer visible. e-h, Stage 8, Segmented germ band. e: Lateral view. Evident are all future prosomal segments: cheliceres (Ch), pedipalps (P) and four walking legs (white arrow heads). At the posterior end, the growth zone (GZ) exhibits a higher density of cells. f: Frontal view of the same embryo as in e. g: Slightly more advanced embryo than e. Anterior to the cheliceral segment (Ch) the precheliceral region (Pc) is separated by a clear margin from the surrounding extra-embryonic (mainly yolk) tissue. All prosomal segments (cheliceres, Ch; pedipalps, P; four walking legs, L1-L4) are distinct. h: Lateral view. An embryo comparable to e. Evident are the germ band (GB) and yolk (Y). The yolk is located in the regions labelled earlier as the dorsal field (DF) and the extra-embryonic (Ee) region.

Figure 5.

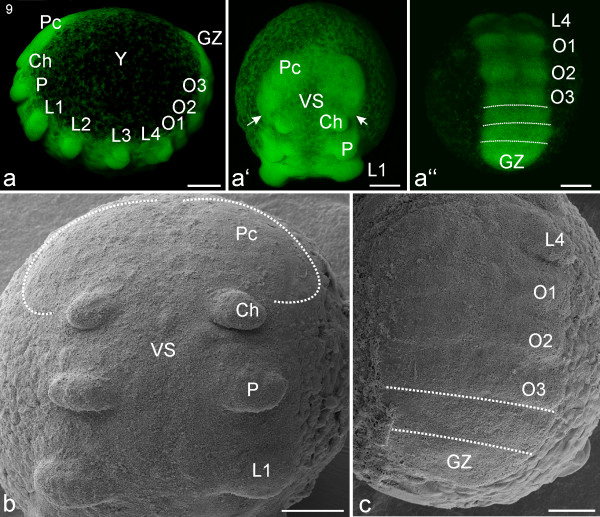

Stage 9, Prosomal limb buds. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs, b, c. a: Lateral view of embryo. The dorsal field (DF) in earlier figures is probably now a mass of extra- and intra-cellular yolk (Y). Also evident are the precheliceral area (Pc), cheliceres (Ch), pedipalps (P), walking legs (L1-L4), opisthosomal segments (O1-O3) and the growth zone (GZ). a': Frontal view. Between the developing appendages the ventral sulcus (VS) is visible as a narrow length of midline tissue with a low cell density compared with the bilateral appendage regions. The white arrows show that the precheliceral region (Pc) extends anteriorly from the anterior base of the cheliceres. a'': Posterior view. The dotted lines indicate the progress of opisthosomal segment formation anterior to the growth zone (GZ). b: Detail of the prosomal region in fronto-ventral view. The white dotted lines indicate the lateral margins of the precheliceral region (Pc). c: Detail of the opisthosomal region. Limb buds are barely evident at this stage on opisthosomal segments 1-3 (O1-O3). The white dotted lines indicate the progress of the formation of additional opisthosomal segments.

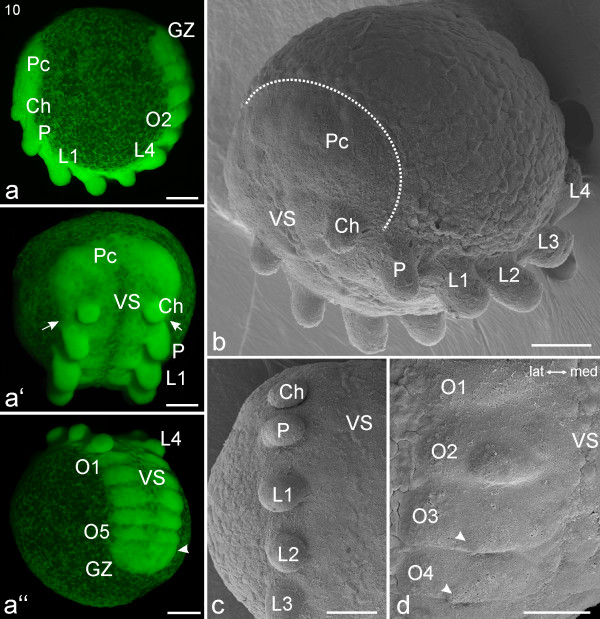

Figure 6.

Stage 10, Prosomal limb bud elongation. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs, b-d. a: Lateral view. Limb buds of pedipalps (P) and walking legs (L1-L4) are prominent in the prosoma, and segments are clearly distinguishable in the opisthosoma (e.g. segment two, O2). a': Frontal view. The white arrows show that the precheliceral region (Pc) extends to the posterior base of the cheliceres (Ch). The ventral sulcus (VS) is a thin length of tissue between the germ band halves. a'': Posterior view. Five segments (O1-O5) with paired bulges are visible in the opisthosoma. A developing sixth opisthosomal segment (white arrowhead) is evident anterior to the growth zone (GZ). b: Embryo in fronto-lateral view. The white dotted line indicates the posterior border of the precheliceral region (Pc). c: Detail of the limb buds in the right prosomal region. d: Detail of the right opisthosomal region. The opisthosomal segment two (O2) has a clear limb bud while opisthosomal segments three and four (O3, O4) only show the beginning formation of the limb bud (white arrowheads).

Stage 6, Dorsal field

This stage is characterised by a major rearrangement of embryonic tissue. Cells between the primary thickening and the cumulus start to migrate laterally, and the dorsal field is formed (DF, Figure 3f). This region is relatively translucent and is made up of far fewer cells than the ventral area where the embryo body will differentiate. Our data does not show whether the dorsal field is formed exclusively by cell migration or whether cell death is also involved. At the same time, the cumulus decreases in size (Figure 3f). As development progresses, the dorsal field expands approximately 100 degrees around the egg surface to form a semicircle, while the cumulus disappears (Figure 3h).

Figures 3g and 3h show that the embryo axes (anterior/posterior and dorsal/ventral) have now been specified as a result of preceding events (compare to [25]). The primary thickening (former blastopore region) will become the posterior end of the embryo body. Figure 3g is a ventral view showing the region of low cell density (extra-embryonic region) at the top of the photo, while the caudal primary thickening is at the bottom. Figure 3h is a posterior view of the dorsal field (DF) that becomes extra-embryonic.

Stage 7, Germ band

At this stage, it is not possible to determine the axis orientation of unstained eggs because of a lack of visible landmarks. When nuclear staining is applied, however, a germ band becomes evident (Figures 4a-d). The germ band is a ventral strip of cells with a convex flexion, bearing the former primary thickening at its posterior end (Figure 4h). This latter region is now called the growth zone (GZ) as in Figures 4a-d. The embryonic tissue expands anteriorly beyond the ventral equator margin (between the white arrows; Figure 4b).

As the germ band becomes visible and gradually lengthens along the ventral curvature, the equator disappears and the dorsal field expands laterally. The equator is evident in Figure 3e (between the white arrow heads) and Figure 4b (between the white arrow heads) but is not evident in Figures 4c, d and later figures. The widening of the dorsal field is evident (white dotted lines) in Figures 4b-d. At the end of this 'Germ band' stage, the embryonic tissue has lengthened anteriorly and covers the entire ventral surface of the embryonic region. In this ventral region of the embryo, the cell density is much greater than in the dorsal field. As a result of cell migration, the cells in the embryonic region become more evenly distributed with only the dorsal field displaying a significantly lower cell density (DF; Figure 4d).

Stage 8, Segmented germ band

Within the spherical eggshell, the embryo now has the shape of a flattened ovoid. The C-shaped germ band invariably lies along the longitudinal egg axis (Figures 4e-h). The developing embryo body (embryo proper) of primordial segments and appendages is very dense, comprising many more cells than the dorsal extra-embryonic tissue (Figures 4e-g). The dense region of cells just anterior to the cheliceres initially has no organized structures (Figures 4e, f) and the border between this region and the extra-embryonic region is less defined than the perimeter of the rest of the embryo body. This precheliceral region (Pc) gradually becomes consolidated into a more distinct structure (Figures 4g, 5a, a'). All future prosomal segments (those of the cheliceres, pedipalps and four walking legs) are visible and distinctly divided by inter-segmental furrows (Figure 4g). The cheliceral segment is slightly smaller than the posterior segments (Figures 4e-g). At its posterior end, the embryo proper has a growth zone (GZ; Figures 4e, g, h) which appears brighter in nuclear staining. The growth zone is rounded posteriorly and has a higher cell density than the remaining embryo proper.

Stage 9, Prosomal limb buds

At this stage (Figure 5a) the border of the embryo proper is more clearly defined than during the previous stage. In the precheliceral region there is often a slight difference in the progression of development of the right and left halves (e.g. Figure 5a'). The lower cell density in the medial precheliceral region marks the start of the formation of the ventral sulcus (VS; Figure 5a') which continues to extend posteriorly into the midline of the anterior segments (cheliceres and pedipalps) of the prosoma (Figures 5b, 6a'). The posterior margins of the precheliceral lobes appear anterior to the cheliceral segment but will gradually extend posteriorly (white arrows; Figures 5a', b). All the prosomal segments are more prominent than in the previous stage, and the prosomal limb buds (cheliceres, pedipalps and four walking legs) bulge outward. The buds are broad and flat and point in a postero-ventral direction (Figures 5a, a', b). The cheliceral buds are smaller and slightly more medial than the buds of the pedipalps and walking legs (Figures 5a, a', b). The opisthosoma has about four visible segment anlagen (Figures 5a, a'', c). The growth zone has a posterior curvature and is less broad than the more anterior segments (Figures 5a'', c).

Stage 10, Prosomal limb bud elongation

For stages 1-9 we adhere to the staging system defined for A. tepidariorum [5,25,44]. However, we deviate from this system at stage 10 as this stage is not well described for A. tepidariorum and has not been used extensively by other authors. Furthermore, stage 10 for A. tepidariorum represents too great an advance from stages 1-9. We define a new stage 10 and new subsequent stages for C. salei. In our stage 10, the embryo has reverted from an ovoid to a largely spherical shape (Figure 6a). The precheliceral region is broader than the remaining parts of the germ band (Figures 6a', b). The posterior margins of the precheliceral region have moved anterior to the pedipalpal segment and now enclose the cheliceral segment (Figures 6a', b).

None of the prosomal limb buds are segmented yet, and they vary in their width-to-length ratio (Figures 6a-c). The slightly depressed ventral sulcus (VS) extends from the centre of the precheliceral region to opisthosomal segment three (Figures 6a', c). The first opisthosomal segment is clearly visible but will eventually disappear (Figure 6d). It is at this point considerably smaller than the subsequent opisthosomal segments. In Figure 6a'' a developing sixth opisthosomal segment (white arrow head) is evident anterior to the growth zone. In older embryos of this stage, limb buds appear on opisthosomal segment two (Figure 6d).

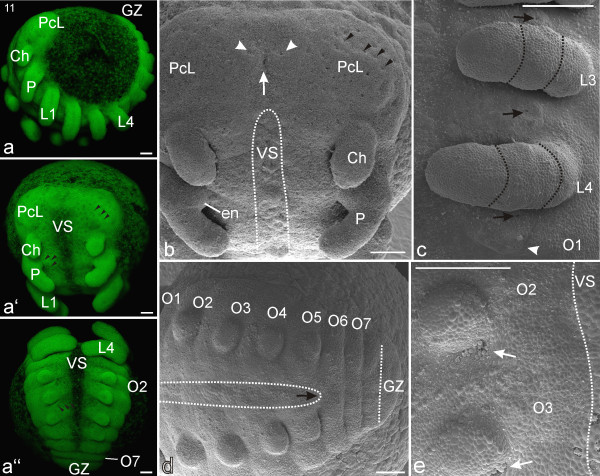

Stage 11, Opisthosomal limb buds

At this stage, the precheliceral region is partitioned medially into bilateral precheliceral lobes (Figures 7a', b). Each lobe has about 30 point-like depressions (invagination sites, sensu [14]) that are presumably neural precursor tissue (black arrow heads, Figure 7b). The anlage of the stomodeum becomes visible. It is formed by a somewhat depressed antero-medial precheliceral region, which bears a small longitudinal furrow with two lateral adjacent invaginating neural precursor groups (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Stage 11, Opisthosomal limb buds. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs, b-e. a: Lateral view. The single precheliceral area (Pc, Figure 6) is now divided into bilateral precheliceral lobes (PcL). a': Frontal view. Laterally adjacent to the ventral sulcus, segmentally iterated point-like depressions are evident (black arrow heads). This is presumably neural precursor tissue. a'': Posterior view. The ventral sulcus (VS) is prominent between the developing limb buds in the prosoma and opisthosoma. b: Frontal view clearly showing that the single precheliceral area in earlier figures is now divided into bilateral precheliceral lobes (PcL). Each of these lobes has evenly distributed point-like depressions (some indicated by black arrow heads). The white arrow shows the postero-medial furrow of the forming stomodeum. Laterally adjacent to it are two conspicuous point-like neural depressions (white arrow heads). At the pedipalps (P), the anlage of an endite (en) is evident as a proximo-medial swelling. c: Detail of left prosomal region. Prosomal limb buds (L3-4) appear three-segmented, and in between the limb buds is a larger invaginating region (black arrows) of presumptive neural precursor cells. Barely visible are the remnants of limb buds (white arrow head) on opisthosomal segment one (O1). d: Opisthosomal region. Seven clearly separated opisthosomal segments (O1-O7) are visible while an additional segment (vertical dotted line) is still connected with the growth zone (GZ). The ventral sulcus (VS, horizontal white dotted lines) extends posteriorly (black arrow) as the limb buds become differentiated e: At the medio-posterior base of the limb buds of opisthosomal segments two and three (O2, O3) are conspicuous depressions (white arrows) made up of primordial tissue for the respiratory system. The white dotted line indicates the right boundary of the ventral sulcus (VS). Ch: chelicere, P: pedipalp.

In older embryos of this stage, the stomodeal anlage has migrated posteriorly, leaving behind a shallow cleft between the precheliceral lobes (Figure 7b). The cheliceral limb buds have become more flattened and are approximately twice as long as they are wide. They have twisted slightly ventro-posteriorly, and their distal parts are cone-like (Figures 7a', b). The pedipalps have a proximo-medial swelling formed by the anlage of an endite (en, Figure 7b). The ventral sulcus has extended posteriorly, reaching the sixth opisthosomal segment in older embryos of this stage (Figures 7a'', d). Small spots (black arrow heads; Figures 7a', a'') in a segmentally iterated pattern are barely visible laterally adjacent to the ventral sulcus. This area is the ventral neuroectoderm and the point-like depressions correspond to neural precursor tissue [27]. In addition, medially and between the developing limb buds, larger spots of neural precursor tissue are observable on the ventral surface of each prosomal segment (black arrows, Figure 7c). Together with the point-like depressions of the precheliceral region (black arrow heads; Figure 7b) they are the first external indications of neurogenesis.

The pedipalps and walking legs continue elongation and start to bend ventrally. Two annulations develop, dividing the limb buds into three regions (black dotted lines; Figure 7c). For a short time, a small structure is visible on the first opisthosomal segment. This small structure can be interpreted as a vestige or remnant of an appendage (white arrow; Figure 7c). With a developmental gradient from anterior (more developed) to posterior (less developed), primordial limb buds have appeared as small bulges on opisthosomal segments two to five (Figures 7a, a'', d). The initial shape of these buds is not as broad as the prosomal limb buds when they first appeared (compare with stage 9; Figures 5a', b). Depressions at the medio-posterior insertion of opisthosomal limb buds two and three can be seen (white arrows; Figure 7e). These invaginations are precursor tissue for the book lung system. At least seven separated segments are visible anterior to the growth zone (Figures 7a'', d).

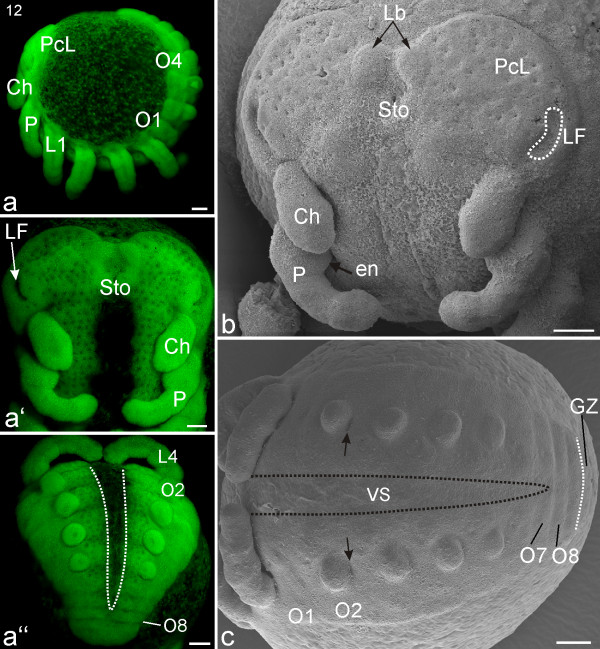

Stage 12, Lateral furrow

The outer edges of the precheliceral lobes have become very distinct, and the lobes stand out clearly from the surrounding tissue (Figures 8a', b). Alongside the point-like depressions, a slight relief begins to form on the precheliceral lobes. Lateral to the stomodeum, invaginating kidney shaped folds of neural tissue are visible (lateral furrow LF; Figures 8a', b). Medially adjacent to these folds a minimal elevation can be seen in some specimens.

Figure 8.

Stage 12, Lateral furrow. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs, b, c. a: Lateral view. a': Frontal view. Lateral to the stomodeum (Sto) are invaginating folds of precursor neural tissue (LF, lateral furrow). The pedipalps (P), cheliceres (Ch), and stomodeum are more pronounced. a'': Posterior view. The walking legs (visible L4) are more elongated and their tips touch each other. The ventral sulcus (VS, white dotted line) extends posteriorly almost the eighth opisthosomal segment (O8). b: Ventro-lateral view. Anterior to the stomodeum (Sto), the small bi-lobed anlage of the labrum (Lb) is visible. Postero-laterally on each precheliceral lobe (PcL), a kidney shaped lateral furrow (LF) is evident. c: Opisthosomal region. Eight separate opisthosomal segments (O1-O8) are visible whilst an additional segment (indicated by a white dotted line) is still connected to the growth zone (GZ). Small depressions (black arrows) of the primordial respiratory system are evident at the posterior insertion of the limb bud at opisthosomal segment two (O2). The ventral sulcus (VS, black dotted line) extends posteriorly to the seventh opisthosomal segment (O7).

The stomodeum has now subsided and moved further posteriorly so that the cleft separating the precheliceral lobes is more evident (Figure 8b). Anterior to the stomodeum, the small bi-lobed anlage of the labrum is visible (Lb; Figure 8b). The prosomal limbs (pedipalp and walking legs) have elongated, and the tips of the walking legs from each body halve approach each other. The pedipalpal endite on the most proximal segment (coxa) is clearly visible (en; Figure 8b). The pedipalps and all the walking limbs display signs of annulations. It is not clear how these annulations relate to later leg segments.

The ventral sulcus extends posteriorly to the seventh opisthosomal segment, and has slightly widened (Figures 8a'', c). All opisthosomal limb buds have a globular shape (Figures 8a'', c). Small depressions of the primordial respiratory system are evident at the posterior insertion of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment two (black arrows; Figure 8c). Medially and between the opisthosomal limb buds, large point-like depressions of neural precursor tissue can be seen. These depressions are similar to the large spots on the prosoma in stage 12 (compare Figure 8c with Figure 7c). Up to eight separate opisthosomal segments are visible anterior to the growth zone (Figures 8a'', c).

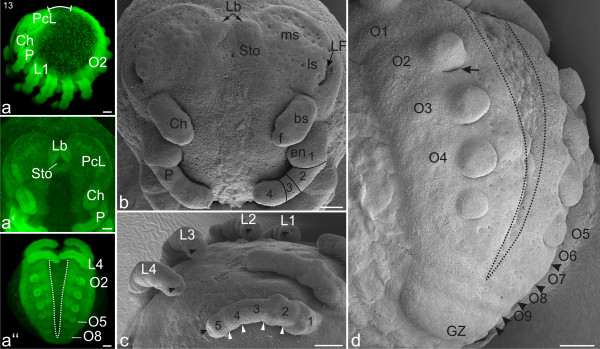

Stage 13, Labrum

The distance between the posterior end of the opisthosoma and the anterior border of the precheliceral lobes is at its smallest at this stage (white line; Figure 9a). In the forming brain, the lateral furrows have deepened (Figure 9b). Two distinct fields of neural precursor tissue are evident within the crescent-shaped precheliceral lobes: the medial subdivision and the lateral subdivision (ms and ls, sensu [37]). These are positioned between the lateral furrow and the anlage of the labrum (Figure 9b). The two lobes of the labrum are clearly evident at this stage (Figure 9b) but are still separate structures (compare with later stages; e.g. Figure 12 b).

Figure 9.

Stage 13, Labrum. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs; b-d. a: Lateral view. Cheliceres (Ch), pedipalps (P) and the four walking limbs (L1-L4) are more prominent in the prosoma. Because of the growth that has taken place along the ventral curvature, the posterior end of the opisthosoma approaches (white line) the anterior border of the precheliceral lobes (PcL). a': Frontal view. Anterior to the stomodeum (Sto) the prominent labrum (Lb) is evident. Cheliceres (Ch) and pedipalps (P) are more pronounced. a'': Posterior view. The ventral sulcus (VS, white dotted line) extends posteriorly to the eighth opisthosomal segment (O8). b: Precheliceral region. Two distinct fields of precursor neural tissue are evident within the crescent-shaped precheliceral lobes: the medial (ms) and lateral (ls) subdivisions. The cheliceres (Ch) have a proximal base (bs) and a distal fang (f). The pedipalp (P) is four-segmented (1-4) and bears an endite (en) on its first segment. c: Prosoma in postero-lateral view. The white arrowheads show that each walking leg (L1-L4) is subdivided into five podomeres (1-5). There is a point-like depression (black arrows) of what is presumed to be neural precursor tissue at the distal tip of each leg. d: Opisthosomal region. Nine opisthosomal segments (O1-O9) are visible while an additional segment is still connected to the growth zone (GZ). Black arrowheads indicate segmental furrows that mark the boundary between opisthosomal segments. A slit-like invagination (black arrow, primordial respiratory tissue) is evident at the posterior base of the limb bud at opisthosomal segment two (O2). The ventral sulcus (black dotted line) extends posteriorly to the eighth opisthosomal segment (O8).

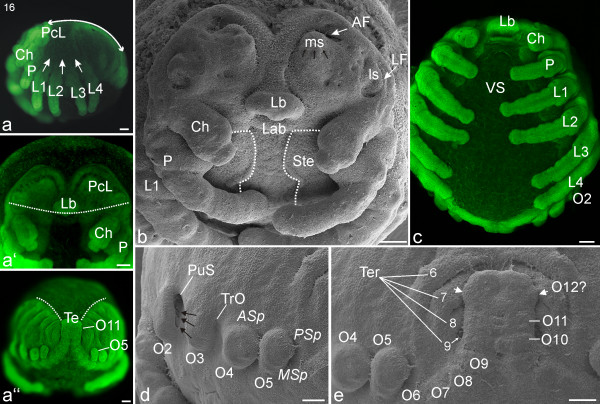

Figure 12.

Stage 16, Inversion III. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a'', c; SEMs, b, d, e. a: Lateral view. The white line indicates the increased distance from the precheliceral lobes (PcL) to the opisthosomal tail compared to previous stages (compare with Figure 10a and 11a). The prosomal tergites start to extend dorsally (white arrows). a': Frontal view. The white dotted line indicates the more posterior position of the mouth opening in relation to the lateral subdivision of the brain (compare with Figures 10a'and 11a'). a'': Posterior view. The white dotted line shows the progress of inversion (see the lower diagram in Figure 11d which schematically illustrates inversion). b: Detail of the head region. The medial subdivision (ms) is growing anteriorly (black arrows), partially covering the anterior furrow (AF). The lateral furrow (LF) is totally covered by tissue from the lateral subdivision (ls). The mouth opening is covered by the medially enlarged tip of the labrum (Lb). Anlagen of the segmental sternites (Ste, white dotted line) are evident medial to the pedipalps (P) and walking legs (L1). c: Ventral view showing all prosomal appendages and the extent of the widening of the ventral sulcus (VS). d: Detail of left anterior opisthosoma. At the posterior base of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment two (O2), three pulmonary furrows (black arrows) and a lateral opening of the pulmonary sac (PuS) are evident. At the latero-posterior insertion of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment three (O3), the opening of the tubular trachea (TrO) is visible. The globular limb bud on opisthosomal segment four (O4) will differentiate into the anterior spinneret (ASp), whereas the dorso-ventrally elongated limb bud on opisthosomal segment five (O5) will differentiate into the posterior (PSp) and medial (MSp) spinnerets. e: Detail of the posterior opisthosomal region. Eight opisthosomal segments (O4-O11) are clearly evident here. On the dorsal surface, the primordial tergite plates (Ter) have further expanded (compare with the later stage in Figure 14c). Between the eleventh opisthosomal segment (O11) and the growth zone (GZ), small bilateral lobes probably represent the twelfth opisthosomal segment (O12?). Ch, chelicere; Lab, labium; Te, telson.

The cheliceres have a proximal base and the anlagen of the distal fangs are visible (f; Figure 9b). The pedipalps and walking legs show clearer annulations and a subdivision into podomeres is evident. The pedipalps are divided into four segments, and the walking legs have five segments (Arabic numbers in Figures 9b, c). The most proximal leg segments (coxa and trochanter/femur) are broader than the more distal leg segments (Figure 9c). Large invagination sites are positioned at the distal tips of the pedipalps and walking legs (black arrows; Figure 9c).

All opisthosomal limb buds retain their globular shape. A slit-like invagination is evident at the posterior base of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment two (black arrow, Figure 9d) and will be the first opening of the primordial respiratory tissue (book lung system). The fifth opisthosomal limb buds are still smaller than the more anterior buds. The opisthosoma has up to nine separated segments and the ventral sulcus, which has again slightly widened, extends posteriorly to the eighth opisthosomal segment (Figures 9a, d).

Stage 14, Inversion I

The gradual widening of the ventral sulcus, which from stage 11 to 13 is a relatively slow process, significantly accelerates during stage 14 (Figures 10a'', e). This marks the start of inversion, a complex sequence of tissue movement and growth that results in a rearrangement of the body and incorporation of the yolk mass into the embryo. Apart from the precheliceral region and the posterior-most opisthosomal segments, the two halves of the germ band move separately over the yolk mass until they connect again on the dorsal side (Figure 11d gives a schematic overview). As a result of this movement, the distance between the precheliceral region and the posterior opisthosomal region increases. Simultaneously, the germ band continues to extend with the addition of the final opisthosomal segments. The precheliceral region, which until inversion was an extension of the rest of the germ band, gradually folds posteriorly. In order to precisely map the various developmental events that occur during inversion, we distinguish four separate stages.

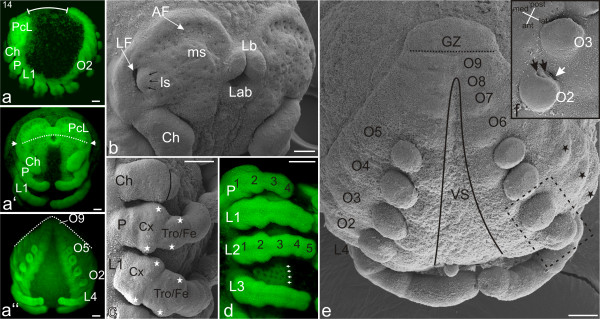

Figure 10.

Stage 14, Inversion I. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a'', d; SEMs, b, c, e, f. a: Lateral view. The distance between the posterior opisthosoma and the anterior border of the precheliceral lobes (PcL) has increased (indicated by white line, compare with Figure 9a). a': Frontal view. Between the precheliceral lobes (PcL) the stomodeum (Sto) has moved posteriorly. The white dotted line shows the more anterior position of the mouth opening in relation to the lateral subdivision (indicated by white arrows) of the brain. a'': Posterior view. The white dotted line shows the progress of inversion (see the upper diagram in Figure 11d which schematically illustrates inversion). b: Head in ventro-lateral view. Anterior to the medial subdivision (ms), the anterior furrow (AF) has formed. The anterior furrow has also been termed semi-lunar or cerebral groove in other arachnids [e.g. [33,45]]. The lateral subdivision (ls) migrates (black arrows) in the direction of the lateral furrow (LF), partly covering it. The mouth opening is surrounded anteriorly by the labrum (Lb) and posteriorly by the labium (Lab). c: Lateral view of right prosomal region. The most proximal limb segments (coxa, Cx and trochanter/femur, Tro/Fe) of the pedipalp and each prosomal limb are widened in anterior-posterior direction (white stars). d: Lateral view of right prosomal region. The ectodermal tissue medial to the prosomal limbs shows a grid-like formation of black spots (white arrows), presumably primordial neural tissue. e: Opisthosomal region. The black line indicates the relative progress of the ventral sulcus (VS). Nine separate opisthosomal segments are present. The black dotted line indicates an additional segment anterior to the growth zone (GZ). The black asterisks designate lobes of anlagen that will eventually become tergites on the dorsal surface of the body. f: Detail of right limb buds of opisthosomal segments two and three (for orientation see dashed-line box in e). At the lateral base of the limb buds of opisthosomal segment two (O2), the opening of the pulmonary sac (white arrow) can be seen. Medially adjacent to it are two slit-like openings (black arrows) to the developing book lungs. Ch, chelicere; L1-L4, walking legs one to four; P, pedipalp.

Figure 11.

Stage 15, Inversion II. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''; SEMs, b, c. a: Lateral view. The white line indicates the increased distance from the precheliceral lobes (PcL) to the opisthosomal tail compared with previous stages (see Figure 10a). a': Frontal view. The white dotted line indicates the mouth opening between the two lateral subdivisions of the developing brain (compare with Figure 10a'). The two labral lobes have completely fused and the labrum (Lb) is now an unpaired structure. a'': Posterior view. The white dotted line shows the progress of inversion (middle diagram in d). b: Opisthosomal region. Separated opisthosomal segments four to nine (O4-9) are visible. The tenth (O10) and the future eleventh segments (black dotted line) are located together with the growth zone (GZ) in a tail-like portion of the germ band that protrudes from the mass of yolk. Small bulges of tergite anlagen (Ter) are evident on the dorsal surface (compare with the more differentiated tergite anlagen in Figure 14c). c: Detail of the right third and fourth walking legs (L3, L4) and the limb buds of opisthosomal segments two and three (O2, O3). At the posterior base of the limb bud of O2 the opening of the pulmonary sac (white arrow) is seen, and adjacent to it medially are two slit-like openings (black arrows) to the book lungs. The podomeres of the fourth walking leg (L4) are numbered (1-5) from base to tip. d: Schematic illustration of the steps of inversion corresponding to stages 14 (compare with Figure 10 a''), 15 (compare with Figure 11 a''), and 16 (compare with Figure 12 a''). Posterior view, dorsal is at the top of the diagrams. The germ band (brown areas) has divided, and the ventral sulcus (VS) is increasing in width. The bilateral regions of the germ band are migrating dorsally (black arrows), enclosing the yolk area (Y) and eventually meeting in the dorsal midline (stage 17, dorsal closure). By stage 15, the dorsal edges of both halves of the germ band lie in a line when viewed from posterior. AF, anterior furrow; Ch, chelicere; P, pedipalp; X, damaged area, cuticle torn.

At Inversion I, the dorsal edges of the body halves have not yet reached the upper hemisphere of the egg. The precheliceral lobes are characterized by a high density of point-like depressions and even more pronounced anterior rims (Figures 10a', b). In addition, the medial and lateral subdivisions are more evident. Anterior to the medial subdivision, a crescent shaped anterior furrow has formed (AF, Figure 10b). The anterior furrow has also been termed the semi-lunar or cerebral groove in other arachnids [e.g. [33,45]]. The lateral subdivision migrates in the direction of the lateral furrow, partly covering it (black arrows; Figure 10b). The cheliceres are now two-segmented. The proximal segment (basal segment) widens distally and the tapering distal segment (fang) sits slightly off-centre on the basal segment (Figure 10c). The proximal segments (coxa and trochanter/femur) of the pedipalps and walking legs are wider than the more distal segments (white stars; Figure 10c). This widening is probably related to anterior and posterior invagination sites on each of these leg segments. The neuroectoderm medial to the prosomal limbs displays a grid-like formation of point-like depressions (white arrows; Figure 10d).

The buds on opisthosomal segment two have become dorso-ventrally elongated. On the posterior ends of these buds, the opening of the pulmonary sac and one or two pulmonary furrows are evident (Figures 10e, f). The buds on opisthosomal segments three to five are undifferentiated and still more or less globular in shape. Dorsal to the opisthosomal limb buds, the anlagen of the tergite plates are evident (black stars; Figure 10e). At the posterior end of the embryo, nine opisthosomal segments have separated from the growth zone (Figures 10a, e). The growth zone now protrudes slightly from the yolk, marking the start of the tail-like formation of the 'post-opisthosoma' (name derived from 'Postabdomen' [46]).

Stage 15, Inversion II

By the second stage of inversion, the lateral/dorsal movement of the body halves has progressed, and the anlagen of tergite plates have extended dorsally (Figures 11a'', d). The opisthosomal body halves have reached the dorsal hemisphere of the egg and form a line when viewed from a caudal perspective (white dotted line; Figure 11a''). The two labral lobes have completely fused and the labrum is now an unpaired structure (Figure 11a'). The labrum and stomodeum have jointly started the posterior migration that will be continued in subsequent stages. By stage 15, the cleft between the two precheliceral lobes has become deeper, and the mouth opening lies between the lateral subdivisions on both head lobes (white dotted line; Figure 11a'). The labrum now partially covers the stomodeum (Figure 11b).

Ten separate opisthosomal segments are evident anterior to the growth zone (Figures 11a'', b). The posterior base of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment two bears two pulmonary furrows (black arrows) and the lateral opening of the pulmonary sac (white arrow; Figure 11c). The tenth and the future eleventh opisthosomal segments are now forming, together with the growth zone of the tail-like post-opisthosoma (Figure 11b). Small bulges of tergite anlagen are evident on the dorsal surface of the opisthosomal segments (Figure 11b).

Stage 16, Inversion III

By the third stage of inversion, the tergite plates of the opisthosoma are completely enclosed within the dorsal hemisphere of the egg: from a caudal perspective the opisthosomal limb buds of both halves lie more or less in one line (Figures 12a'', 11d). The distance between the precheliceral lobes and post-opisthosoma has increased and is about a quarter of the total circumference of the embryo (Figure 12a). The lateral furrows are completely covered by tissue from the kidney-shaped lateral subdivisions (Figure 12b). The medial subdivisions are growing anteriorly, partially covering the anterior furrows (black arrows; Figure 12b). The anterior furrows are partially closed by anterior expansions of medial subdivisions (Figure 12b). The tip of the labrum is stretched medially and points in a ventral direction (Figures 12a', b). Posterior to the stomodeum, the unpaired anlage of the labium is formed (Figure 12b). The mouth area (labrum, stomodeum and labium) has migrated further and lies posterior to the lateral furrow/lateral subdivision, on a level with the insertion of the cheliceres (white dotted line; Figure 12a'). The bases of the cheliceres have further widened, and at the ventral base of the pedipalp a prominent endite is evident (Figure 12b). The coxae of the pedipalps and walking legs still have a 'bi-lobed' appearance, and these appendages have elongated (Figures 12a, c). Anlagen of the segmental sternites become visible medial to the pedipalps and walking legs (white dotted line: Figure 12b). The prosomal tergites start to extend dorsally (white arrows; Figure 12a).

The posterior base of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment two bears three pulmonary furrows (black arrows) and the lateral opening of the pulmonary sac (PuS, Figure 12d). At the latero-posterior insertion of the limb bud on opisthosomal segment three, the invagination of the tubular trachea is visible (white arrow; Figure 12d). The globular limb bud on opisthosomal segment four will eventually differentiate into the anterior spinneret (ASp), while the dorso-ventrally elongated limb bud on opisthosomal segment five will differentiate into the posterior (PSp) and medial (MSp) spinnerets (Figure 12d).

On the dorsal surface, the opisthosomal tergite plates have further expanded, and their dorsal edges start to approach each other (Figures 12a'', e). Eleven opisthosomal segments have formed anterior to the growth zone. In between the eleventh opisthosomal segment and the growth zone (GZ), small bilateral lobes probably represent the twelfth opisthosomal segment (arrowheads; Figure 12e).

Stage 17, Dorsal closure

Dorsal closure completes inversion. The tergites of both body halves meet along the dorsal midline, covering all of the dorsal yolk with embryonic tissue. This gradual event starts posteriorly with the tergites of the caudal region and progresses anteriorly. The laterally expanding tissue of the prosomal tergites meets the tissue posterior to the precheliceral lobes (white arrows; Figure 13b). During the process, the dorsal prosomal surface has a crumpled appearance (Figure 13b). Underneath the area where the tergite plates touch each other, tissue that eventually forms the heart becomes evident (Figure 13a'''). Cuticle covers the sternites in the prosoma (white arrows; Figures 13c) and the brain region is also overgrown by epidermal and cuticular formations (white arrow; Figure 13a'). The embryonic tissue anterior to the pedipalp has bent posteriorly, marking the start of the process in which the supraoesophageal area folds onto the suboesophageal area. As a result of the positioning of the cheliceres and stomodeum, the labrum is positioned between the bases of the cheliceres (Figures 13a'. c). The pedipalps and walking legs have further extended and meet each other medially in a zipper-like manner. The posterior sides of the limb buds on opisthosomal segment two have become concave (Figure 13d). Evident on each bud are four pulmonary furrows (Figure 13d; black arrows) and the opening of the pulmonary sack (Figure 13d; white arrow). The segments posterior to opisthosomal segment eight have become compressed, giving them a swollen appearance (Figure 13e).

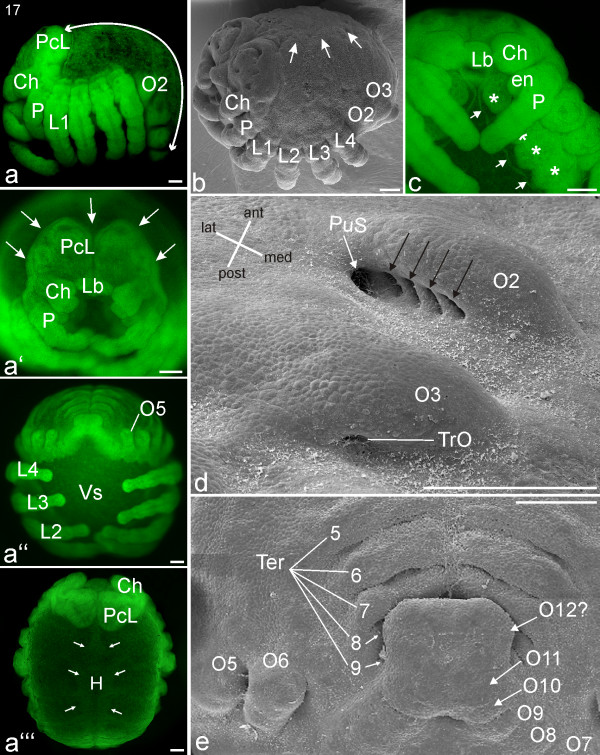

Figure 13.

Stage 17, Dorsal closure. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a''', c; SEMs, b, d, e. a: Lateral view. The white line indicates the increased distance from the precheliceral lobes (PcL) to the opisthosomal tail compared to previous stages (compare with Figure 12a). a': Frontal view. The white arrows indicate the direction of the epidermal and cuticular overgrowth of the brain region. a'': Posterior view. a''': Dorsal view. The white arrows indicate the dorsad growth of tissue that eventually forms the heart (H). b: Dorso-lateral view showing the crumbled appearance of the dorsal tissue directly posterior to the head lobes after dorsal closure. The prosomal tergites continue to extend dorsally (white arrows) (compare with Figure 12a). c: Detail of anterior prosoma. As a result of the forward positioning of the cheliceres and/or posterior positioning of the stomodeum, the labrum (Lb) is now between the bases of the cheliceres (Ch). Cuticular formations (white arrows) are visible in the sternal regions (white asterisks) of the prosomal segments. d: The right limb bud on opisthosomal segment two (O2) shows four pulmonary furrows (black arrows) and a lateral opening of the pulmonary sac (PuS). At the latero-posterior insertion of the limb bud at opisthosomal segment three (O3), the opening of the tubular trachea (TrO) is visible. e: Posterior opisthosomal region. The anlagen of the left and right tergite plates (Ter) meet dorso-medially (compare with a later stage, Figure 14c). en, endite; L1-L4, walking legs one to four; P, pedipalp; VS, ventral sulcus.

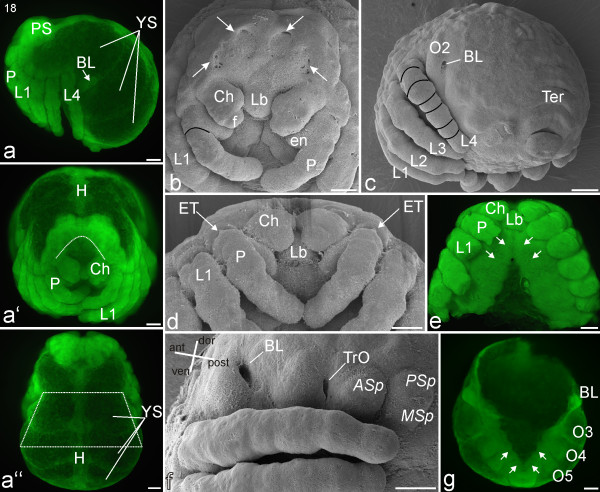

Stage 18, Prosomal shield

The rim of the precheliceral lobes grows in the direction of the mouth opening and covers the brain, which has thickened substantially (Figures 14a, a'', b). The lateral and medial subdivisions are the last parts of the brain to be overgrown. Dorso-posteriorly to the precheliceral region, cuticle continues to expand marking the start of the formation of the prosomal shield (white arrows; Figure 14b). The labrum is now posterior to the cheliceres, which in frontal view partially cover the labrum with their bases (Figures 14a', b, e). Tiny egg teeth appear laterally on the most proximal segment of the pedipalps (ET; Figure 14d). The walking legs are more slender than before and show their final segmentation into seven podomeres (black lines; Figure 14c).

Figure 14.

Stage 18, Prosomal shield. All scale bars 100 μm. Sytox staining, a-a'', e, g; SEMs, b-d, f. a: Lateral view. The dorsal yolky mass is divided into three distinct yolk sacs (YS). a': Frontal view. The dotted white line shows the position of the labrum posterior to the cheliceres, which partially cover it with their bases. a'': Dorsal view. The top of the white (dotted line) trapezoid designates a narrowing region that will eventually become the petiolus, a short length of thin connecting tissue between the prosoma and opisthosoma as shown in Figure 18g and 19b. The base of the trapezoid indicates the broader opisthosoma that continues in advanced stages (e.g. Figure 18g, 19a). The heart primordium (H) is evident in the dorsal midline. b: Frontal view. The anterior brain region is almost covered by the prosomal shield (white arrows). c: Postero-lateral view. The elongated walking legs (L1-L4) show their final segmentation into seven podomeres (black lines). The second opisthosomal segment (O2) shows a prominent opening for the book lung system (BL). d: Tiny egg teeth (ET) appear laterally on the most proximal segment of the pedipalps (P). e: Ventral view of the prosoma, with the legs trimmed. The sternites start to fuse medially from anterior to posterior (white arrows) in a process that will eventually result in a single sternal plate. f: Lateral view of the left opisthosomal region in a late stage 18. The broad openings (primordial spiracles) of the book lung system (BL) and the tracheal (TrO) systems are clearly visible. g: Ventral view of the opisthosoma; the prosoma is cut off (same embryo as in e). The opisthosomal sternites start to fuse medially from posterior to anterior (white arrows). Asp, anlage of anterior spinneret; Ch, chelicere; en, endite; f, fang; Lb, labrum; MSp, anlage of medial spinneret; O3-O5, opisthosomal segments three to five; PS, prosomal shield; PSp, anlage of posterior spinneret; Ter, tergite.

The dorsal yolky mass is divided into at least three distinct yolk sacs (YS; Figures 14a, a''). In parallel, yolk moves from the prosomal segments into the posterior part of the embryo, while simultaneously the petiolus starts to constrict, causing the embryo to lose its spherical shape. Together, these events mark the start of the division into what will later become the tagmata (prosoma and opisthosoma). The opisthosoma has grown in relation to the rest of the embryo: at this stage the width of the petiolus is about 60-70% of the width of the opisthosoma (trapezoid line; Figure 14a'').

Opisthosomal segments two, three and four broaden substantially, especially at their dorsal ends, giving the embryo a crooked appearance (Figures 14a, c). The third opisthosomal segment widens ventrally, with the result that the distance between the book lung primordia and the tracheal tubercles increases (Figure 14g). Ventral closure initiates: The anlagen of the prosomal sternites start to close from anterior to posterior in a process that will eventually result in a single sternum plate (white arrows; Figure 14e). The sternites posterior to opisthosomal segment five have also moved closer together (white arrows; Figure 14g). The most posterior opisthosomal segments, probably segments nine to twelve, have swollen up even more ventrally and form a square-shaped protrusion (Figures 14a, c, g).

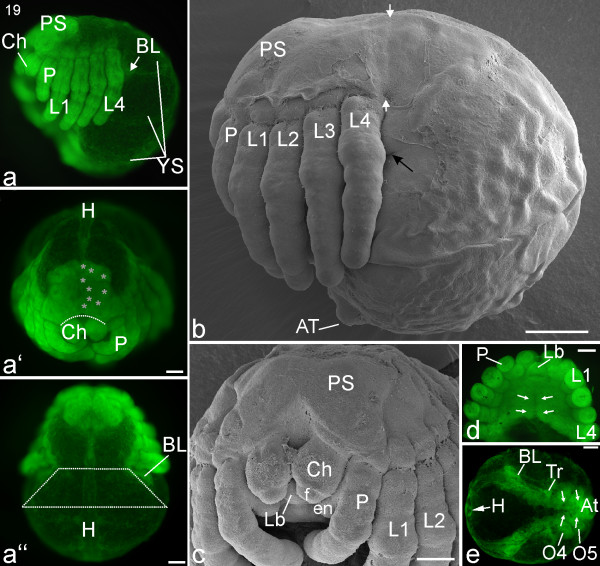

Stage 19, Heart

The protocerebral part of the brain no longer sits on the yolk but has sunk into the prosoma (Figure 15a). The prosomal shield has almost completely covered the brain, save for a wedge-shaped opening directly dorsal to the cheliceres (white dotted line; Figure 15a'). In frontal view, the labrum is now fully covered by the cheliceres (Figures 15a', c). The labium has started to protrude, and together with the labrum forms a beak-like structure. Posterior to the mouth, the prosomal sternites have fully closed (white arrows; Figure 15d). The prosomal tergites are dorso-ventrally reduced, and the inserts of the pedipalps and walking legs have moved dorsally (Figures 15a, a'', b). From a lateral perspective, the brain and the inserts of the walking legs no longer form a continuous arch but lie at an acute angle to each other. All in all, the prosoma has become more compact, a process probably also accompanied by further movement of yolk from the prosoma into the opisthosoma.

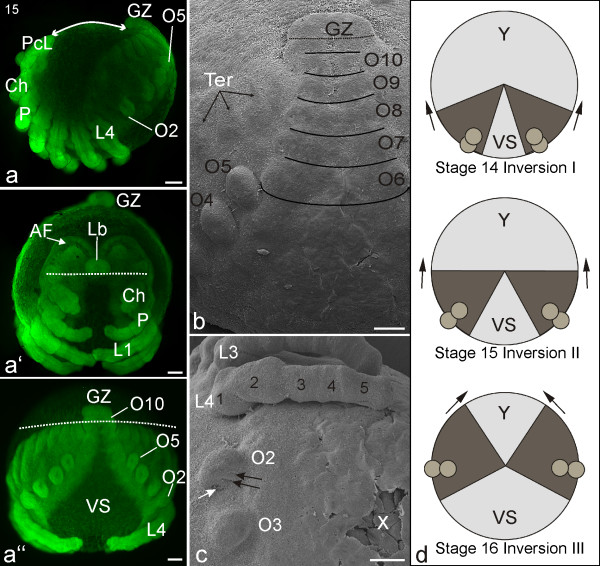

Figure 15.

Stage 19, Heart. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-a'', d, e; SEMs, b, c. a: Lateral view. BL indicates an internal mass of cells that will become book lung tissue. The brain region has sunk into the prosoma (compare with earlier stages, e.g. Figure 18a) and is partially covered by the prosomal shield (PS). a': Frontal view. The dotted line indicates the advancing edge of the prosomal shield that will eventually cover the brain region. The grey asterisks (on the left half of the body only) show that the brain has differentiated into interconnected lobes. a'': Dorsal view. As described in the legend for Figure 14, the top of the trapezoid (white dotted lines) spans the narrowing region that will become the petiolus while the base of the trapezoid shows the continuing breadth of the opisthosoma. The tubular heart (H) is developing in the dorsal midline and is the main identifying feature for this stage. b: Lateral view. A suture between the prosoma and opisthosoma is visible (white arrow heads). Some embryonic cuticle was torn off, exposing the opening of the book lung system (black arrow). The posterior-most segments of the opisthosoma are further compressed and together form the anal tubercle (AT). c: Frontal view. The brain region is almost completely covered by the prosomal shield (PS) and the labrum (Lb) lies ventral to the cheliceres (Ch). d: Ventral view of the prosoma. The legs are trimmed to show the medially fused sternites (indicated by white arrows) of all prosomal segments. e: Ventral view of an opisthosoma separated from the prosoma (same embryo as d). White arrows indicate the progress of the ventral closure of opisthosomal sternites. The tubular heart (H) is seen in cross section as a circular structure. BL, book lung system; en, endite; f, fang; L1-L4, walking legs one to four; O4, O5, opisthosomal segments four and five; P, pedipalp; Tr, tracheal system.

The petiolus has constricted further, and at this stage is about 50-60% of the width of the opisthosoma (trapezoid line; Figure 15a''). Dorsally on the opisthosoma, nuclear staining shows a tubular heart (Figures 15a'', e). Ventrally, the opisthosomal sternites have not yet fully closed. Due to a broadening of the sternite of opisthosomal segment three, the book lung primordia have migrated anteriorly and are now almost completely lateral to the petiolus (Figure 15a''). The posterior-most segments of the opisthosoma have further compressed and together form the anal tubercle (Figure 15b).

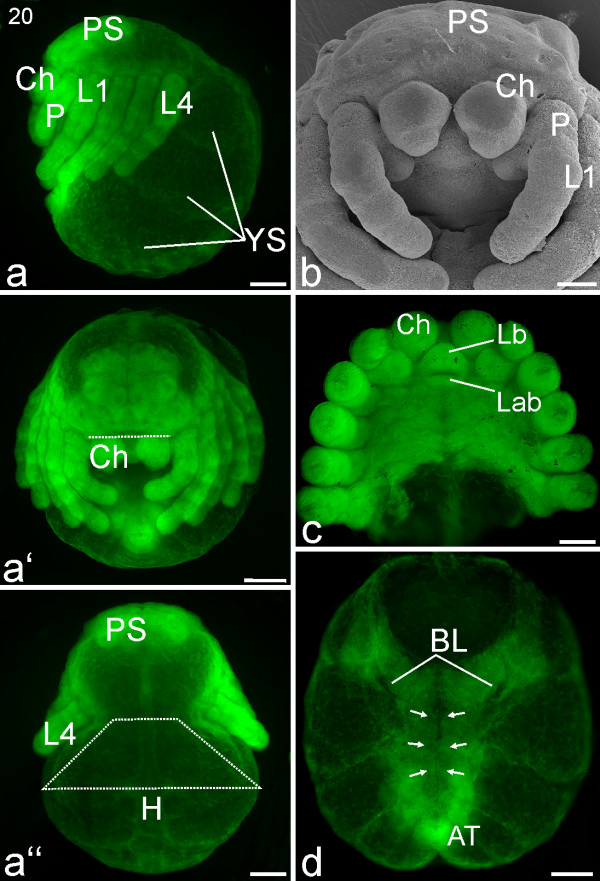

Stage 20, Ventral closure

Nuclear staining of the developing brain shows distinct regions that correspond to brain parts such as the optic ganglia (Figure 16a). The prosomal shield covers the whole prosoma, including the brain region directly dorsal to the labrum (Figures 16a, a', b). The cuticular border of the prosomal shield is now visible between the prosoma and the opisthosoma (Figure 16b). In lateral view, the insertion sites of the walking appendages lie in a straight line (Figure 16a). The width of the petiolus is about 40-50% of the width of the opisthosoma (trapezoid line; Figure 16a''). The embryo has become even more crooked, such that the first pair of walking legs almost touches the anal tubercle (Figures 16a, a'). Ventral closure of the opisthosoma is complete, and the book lungs have moved antero-medially in the direction of the petiolus (Figure 16d). The spinnerets of both body halves lie close together and form the spinning field. The spinning field has moved close to the anal tubercle (AT; Figures 16a', d).

Figure 16.

Stage 20, Ventral closure. All scale bars 200 μm. Sytox staining, a-a'', c, d SEM b. a: Lateral view. Three yolk sacs (YS) are visible in the opisthosomal region. The brain region is fully covered by the prosomal shield (PS). a': Frontal view. The dotted line indicates the advancing edge of the prosomal shield that at this point fully covers the brain region. a'': Dorsal view. As described in the legend for Figure 14, the top of the trapezoid (white dotted lines) spans the narrowing region that will become the petiolus while the base of the trapezoid shows the continuing breadth of the opisthosoma (compare with Figures 14a'', 15a''). b: Fronto-ventral view of the prosoma. c: Ventral view of the prosoma, legs are trimmed. d: Ventral view of the opisthosoma. The prosoma is cut off so the medial growth of the sternites (arrows) can be seen in the process of ventral closure (same embryo as b). AT, anal tubercle; BL, book lung system; Ch, chelicere; H, heart; L1-L4, walking legs 1-4; Lab, labium; Lb, labrum; P, pedipalp; YS, yolk sac.

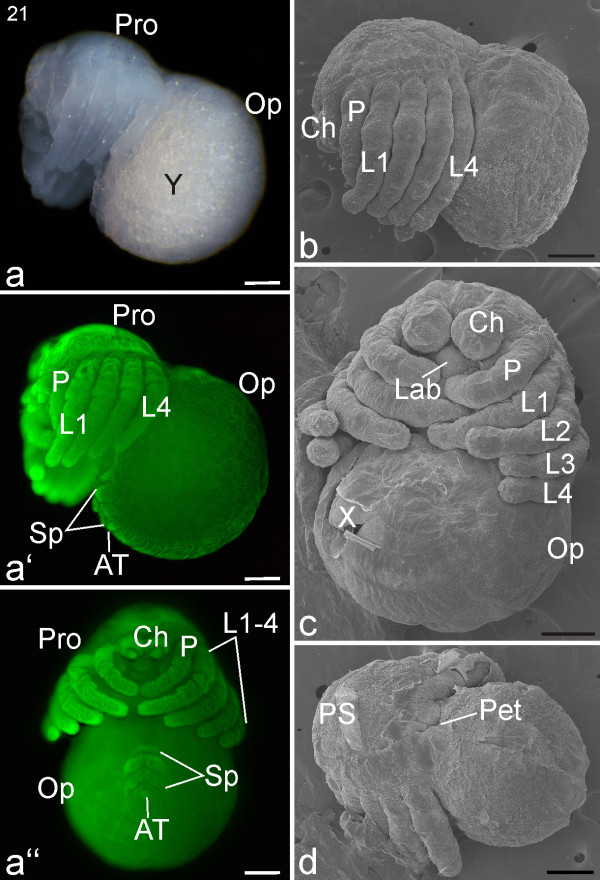

Stage 21, Petiolus

In the course of this stage, a complete cuticle develops underneath the embryonic cuticle, making it impossible to obtain information about the inner morphology using nuclear staining of whole mounts. Externally, the fangs of the cheliceres become pointed and are directed towards each other (Figures 17a'', c). The final restriction of the petiolus takes place; the embryo starts unfolding and loses its crooked appearance (Figures 17a-d). Seitz [26] observed in advanced embryos (probably corresponding to stage 21) that lateral parts of the prosoma had not yet been fully covered by the dorsal shield. We cannot confirm this however. Towards the end of this stage, air appears between the prosomal appendages, indicating that the embryo is taking up the exuvial liquid which will allow it to exert pressure on the egg membranes (white arrow; Figure 18a).

Figure 17.

Stage 21, Petiolus. All scale bars 200 μm. Light micrograph, a; Sytox staining, a', a''; SEMs, b-d. a: Lateral view. A narrowing region (petiolus) connects the prosoma (Pro) and opisthosoma (Op). The colour of the opisthosoma is distinct from the prosoma due to the large proportion of yolk (Y) a': Lateral view of same embryo as in a. The prosomal shield (PS) is clearly evident, as are the differentiating spinnerets (Sp). a'': Ventral view, same embryo as in a and a'. The lobes of the spinnerets (Sp) and anal tubercle (AT) are prominent. b: Lateral view. c: Ventral view. d: Dorsal view. The SEMs of b, c and d show that the swollen opisthosoma is connected to the prosoma by a narrowing petiolus (Pet). The appendages are long and segmented, and the prosomal shield (PS) is prominent. Due to a cuticle cover (torn edges evident in c), the opisthosomal surface shows little indication in SEM images of the spinnerets that are evident with Sytox staining in a''. Ch, chelicere; L1-L4, walking legs one to four; X, damaged area, cuticle torn.

Figure 18.

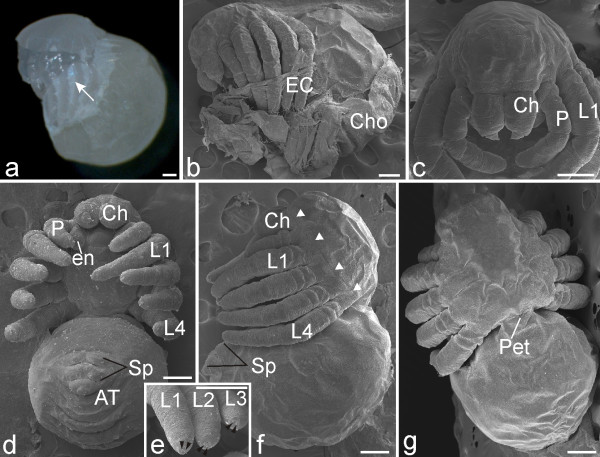

Hatching and Postembryo of C. salei. All scale bars 200 μm. Light micrograph, a; SEMs, b-g. a: Lateral view of a live hatching embryo. White arrow points toward air underneath the egg membranes. This air space between the membranes and the embryo surface becomes evident shortly before hatching. b: Lateral view of hatching embryo with chorion (Cho) and embryonic cuticle (EC) partially removed. c: Frontal view of newly hatched postembryo. d: Ventral view of postembryo. The spinneret anlage (Sp) is now clearly evident as bilateral bulges in the ventral opisthosoma. e: Detail of the tips of the walking legs of the postembryo. Black arrowheads indicate tarsal claws. f: Lateral view. White arrowheads mark the line where the cuticle of the postembryo will eventually break for the first moult to first instar. g: Dorsal view. The narrow petiolus (Pet) connects the prosoma and opisthosoma. AT, anal tubercle; Ch: chelicere; en, endite; L1-L4, walking legs one to four; P, pedipalp.

Postembryonic stages

Postembryo

Eclosion marks the end of the embryonic stages. In C. salei, this process includes the rupturing of the egg membranes and moulting from the embryonic cuticle (EC; Figure 18b). The rupturing of the egg membranes invariably starts around the pedipalps, and is likely initiated by the pressure of the egg teeth on the membranes. The embryonic cuticle, which bears the egg teeth, also opens along a predetermined breaking line around the carapace (Figures 18a, b). The resulting stage, which we name the 'postembryo' after [47] is completely immobile. The outer appearance is very similar to late embryonic stage 21, with legs that still bend ventrally. However, once released from the egg membranes, the postembryo is completely unfolded. The spinnerets and anal tubercle become more pronounced (Figures 18c-g) and the first pigments can be seen in the eyes. The pointed fangs have not yet fully extended (Figure 18c) and the endite of the pedipalps does not touch the other mouth parts (Figure 18d). The postembryo has two tiny tarsal claws on the tip of each leg (black arrow heads; Figure 18e). No sensory hairs are visible on the cuticle.

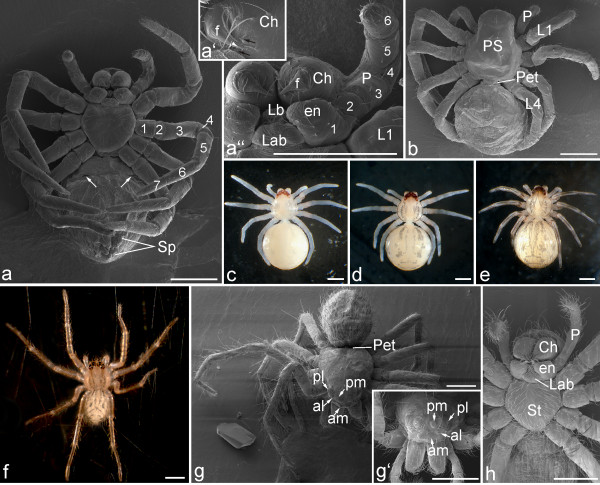

First instar

The first instar emerges from the postembryo after about 3 days (at 25 C). Contrary to earlier observations [48] we never witnessed a first instar hatching directly from the egg. The walking legs of the first instar extend laterally (Figures 19b, c-e). The cheliceres have two so-called retromarginal teeth on their bases (black arrows; Figure 19a'). Both teeth are positioned opposite the folded fangs. Distal-laterally, the fangs bear an opening to the poison gland (white arrow head; Figure 19a').

Figure 19.

First and Second instar of C. salei. All scale bars 500 μm. SEMs, a-b, g-h; light micrographs, c-f. a-e First instar. a: Ventral view. Numbers indicate the seven podomeres of L2. White arrows indicate the slit-like opening of the book lung system. a': Detail of the tip of the left chelicere showing the fang (f), a sharp cuticular claw on which the opening of the poison gland is visible (white arrow head). Black arrows indicate the retromarginal teeth at the base of the chelicere. a'': Detail of the mouth region. Numbers indicate the six podomeres of the pedipalp. b: Dorsal view. c-e: Dorsal view of increasingly older first instars, illustrating the increase in pigmentation. f-h Second instar. f: Dorsal view. g: SEM image. Dorsal view shows the arrangement of the eyes (al: anterior lateral eye, am: anterior median eye, pl: posterior lateral eye, pm: posterior median eye) and the petiolus (white arrow). g' Frontal view. Higher magnification of the eye region of g. h: Ventral view. The mouth opening is surrounded antero-laterally by the two cheliceres (Ch), laterally by the endites (en) of the pedipalps (P) and posteriorly by the labium (Lab). The labrum anterior to the mouth opening is covered by the cheliceres. L1-L4, walking leg one to four; Lb, labrum; Pet: petiolus; PS, prosomal shield; Sp, spinnerets; St, sternum.