Abstract

To generate broadly protective T cell responses more similar to those acquired after vaccination with radiation-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites, we have constructed candidate subunit malaria vaccines expressing six preerythrocytic antigens linked together to produce a 3,240-aa-long polyprotein (L3SEPTL). This polyprotein was expressed by a plasmid DNA vaccine vector (DNA) and by two attenuated poxvirus vectors, modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) and fowlpox virus of the FP9 strain. MVAL3SEPTL boosted anti-thrombospondin-related adhesive protein (anti-TRAP) and anti-liver stage antigen 1 (anti-LSA1) CD8+ T cell responses when primed by single antigen TRAP- or LSA1-expressing DNAs, respectively, but not by DNA-L3SEPTL. However, prime boost regimes involving two heterologous viral vectors expressing L3SEPTL induced a strong cellular response directed against an LSA1 peptide located in the C-terminal region of the polyprotein. Peptide-specific T cells secreted IFN-γ and were cytotoxic. IFN-γ-secreting T cells specific for each of the six antigens were induced after vaccination with L3SEPTL, supporting the use of polyprotein inserts to induce multispecific T cells against P. falciparum. The use of polyprotein constructs in nonreplicating poxviruses should broaden the target antigen range of vaccine-induced immunity and increase the number of potential epitopes available for immunogenetically diverse human populations.

There is no vaccine available against the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, which kills 1–2 million mainly African children a year. The changing molecular patterns displayed by the parasite during its distinct developmental stages suggest that subunit vaccines incorporating multiple antigens would be more effective than single-antigen constructs (1). The complete protection generated by vaccination with radiation-attenuated sporozoites in animal models and in humans (2, 3) supports the feasibility of a preerythrocytic vaccine. Such a vaccine could eliminate, or reduce to a subclinical level, the number of parasites that emerge from infected hepatocytes to initiate the red cell phase of the life cycle that is responsible for the clinical manifestations of malaria (4). The infected hepatocyte may present parasite-derived peptides on MHC molecules to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (5) thereby initiating specific adaptive immune responses. In murine models of vaccination with attenuated sporozoites, CD8+ T cells, probably through the secretion of IFN-γ (6), initiate a cascade of events ending with the destruction of intrahepatic parasites (7–10). The importance of specific T cell responses is emphasized by the selective pressure the parasite exerts on HLA haplotypes in endemic areas (11).

Evaluation of subunit malaria vaccines in rodents suggests that protection against the preerythrocytic stages requires a high level of specific IFN-γ-secreting T cells (12). Powerful immunogenic vaccines based on prime boost regimes with heterologous vectors expressing the same antigen have protected mice in challenge experiments using live sporozoites (13). Strong protective CD8+ T cell responses were induced after DNA priming followed by boosting with recombinant poxviruses, either modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) or other vaccinia strains (14, 15). Recent studies show that recombinant fowlpox (FP9 strain) and recombinant adenovirus are as effective as DNA as priming agents in the murine parasite model Plasmodium berghei (ref. 16 and R. J. Anderson, unpublished work).

Experimental evidence obtained in DNA-vaccinated macaques for AIDS illustrates the potential of pathogens to escape vaccine-induced cellular response (17, 18). In a rodent malaria model, the combination of two DNA vaccines, each expressing a different antigen, conferred a somewhat higher level of protection in mice than when either plasmid was used alone (19).

We describe the construction of a multiantigen vaccine, with the aim of increasing the breadth of the vaccine-induced immune responses to try to circumvent potential P. falciparum escape mutants. Preerythrocytic antigens were chosen on the basis of immunological studies conducted in malaria-endemic areas and in volunteers immunized with radiation-attenuated sporozoites (20–22). A sequence coding for six P. falciparum antigens linked together was constructed. It yielded a 3,240-aa-long hybrid polyprotein called L3SEPTL, containing from the N to the C terminus, liver stage antigen-3 (LSA3) (23), sporozoite threonine and asparigine rich protein (STARP) (24), exported protein-1 (Exp1) (25), Pfs16 (26), thrombospondin-related adhesive protein (TRAP) (27), and liver stage antigen-1 (LSA1) (refs. 28 and 29 and Fig. 1). LSA3 (23, 30) STARP (24), and Exp1 (25) are also expressed in blood stages, and Pfs16 is also found in sexual stages (31). TRAP plays a role in sporozoite motility and hepatocyte targeting and entry (32) and is the target of CD8+ T cell responses in attenuated sporozoite-immunized volunteers (33). LSA1 is expressed only in infected hepatocytes (28). The antigen sequences were inserted into plasmid DNA vectors and two poxviruses: FP9, an attenuated strain of fowlpox virus, and MVA. Although CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are both involved in the adaptive cellular response, CD8+ T cells seem to be of most importance in protective immunity against the preerythrocytic stages (5, 34). Therefore, this study focuses on induced CD8+ T cell responses.

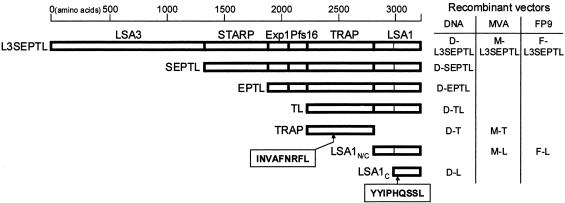

Fig. 1.

Map of the polyprotein L3SEPTL containing from the N- to the C-extremity LSA3, STARP, Exp1, Pfs16, TRAP, and LSA1 antigens. The shorter polyproteins used in the study are also shown. The thin vertical line in LSA1 marks the repeat area deletion leaving the nonrepeated N- (148 aa) and C-terminal ends (286 aa) (LSA1n/c, 436 aa) of the original LSA1 sequence (1,909 aa) (29). Also shown are the single antigens TRAP (559 aa), LSA1n/c and LSA1c (287 aa). The TRAP nonapeptide position is 194–202 in TRAP (27) and 2430–2438 in L3SEPTL. The LSA1 nonapeptide position is 49–57 in LSA1c, 197–205 in LSA1n/c, 1671–1679 in the original LSA1 sequence (1,909 aa) (29), and 3002–3010 in L3SEPTL.

Here, we describe the use of these vectors expressing L3SEPTL in prime boost combinations. We show that (i) MVA-L3SEPTL can boost CD8+ T cell responses after DNA priming with single antigen constructs as efficiently as MVAs expressing TRAP or LSA1 alone; (ii) L3SEPTL is adequately expressed in vivo by both MVA and FP9 fowlpox viruses; (iii) a strong CD8+ T cell response is induced against a nonapeptide in the LSA1 moiety of L3SEPTL by the use of heterologous viral vectors in a prime-boost vaccination regime, but not with the DNA polyprotein vector as a priming agent; (iv) the magnitude and characteristics of the immune response induced to the major LSA1 CD8+ T cell epitope by the poxvirus-encoded recombinant antigens, L3SEPTL (3,240 aa) or LSA1 (436 aa) are similar; (v) T cell responses specific for each of the six antigens were induced after vaccination with FP9-L3SEPTL.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Culture Media. Splenocyte culture and functional assays were performed in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FCS (Globefarm, Esher, U.K.) and antibiotics. Single cell suspensions of primary chicken embryo fibroblasts were obtained by mechanical dislocation and trypsin digestion of 11-day-old pathogen-free chick embryos (Institute of Animal Health, Compton, U.K.) and grown in DMEM 10% FCS with antibiotics.

Animals and Peptides. Four- to 6-week-old female C57BL/6 (H-2b) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice were obtained from Harlan Orlac (Shaws Farm, Blackthorn, U.K.). The animals were handled according to Home Office Animals Act 1986 (Scientific Procedures) guidelines. CD8+ T cell-restricted peptides from PfTRAP (PfTRAP191–210) (identified by G. Voss, GlaxoSmith-Kline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) and PfLSA1 (PfLSA11660–1679) (identified by D. Doolan, Naval Medical Research Institute, Forest Glen, MD) were further narrowed to nonamers by comparison with peptide motifs for MHC class I (35); TRAP194–202 (INVAFNRFL, H-2 Kb) and LSA11671–1679 (YYIPHQSSL, H-2 Kd) (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL).

DNA Vaccine. The details of the genetic construct coding for the polyprotein L3SEPTL (Fig. 1) has yet to be described (E.P., unpublished data). The sequences coding for PfTRAP, the C-terminal end of LSA1, and all of the polyproteins were inserted downstream of the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter in the plasmid pSG2 (16). The DNA vaccines were purified by anion-exchange chromatography (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and diluted in endotoxin-free PBS (Sigma).

Recombinant MVA. The LSA1 sequence modified to leave both the N- and C-terminal nonrepeat regions either side of one residual repeat together with the remaining antigens (Fig. 1) were introduced into the vaccinia shuttle plasmid pSC11 downstream of the early/late vaccinia promoter p7.5. Recombinant viruses were obtained after infection with wild-type MVA of a monolayer of recombinant pSC11-transfected chicken embryo fibroblasts and selected as described in ref. 36.

Recombinant Fowlpox Virus. The LSA1 and L3SEPTL coding sequences were inserted into the shuttle plasmid FP-GFP (S.C.G., unpublished data) targeting the terminal repeats of the fowlpox virus strain FP9 genome (a gift from M. Skinner, Institute of Animal Health). This vector contains a cassette for expression of the GFP, which permitted the rapid sorting of recombinant fowlpox virus-infected single chicken embryo fibroblasts with a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSVantage, Becton Dickinson). MVA and FP9 viral stocks were prepared by purification on a sucrose cushion and stored in endotoxin-free PBS at -80°C until use.

Immunization Procedure. Twenty-five micrograms of DNA was injected into each musculus tibialis in a 50-μl volume under general anesthesia. Poxviruses were given in the tail vein in 100-μl volume. All prime boost regimes involved a 2-week interval between the first and second immunization.

Tetramer Staining and Antibodies. The H-2 Kb-INVAFNRFL and H-2 Kd-YYIPHQSSL phycoerythrin-labeled tetramers (Tet. TRAP and Tet. LSA1) were synthesized by a method that has been described (37). The mAbs to mouse CD8β and CD45R Ly-5 (B-220+, Pan-B cell antibody) Tri-Color- and FITC-labeled, respectively, were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Caltag, South San Francisco, CA). Splenocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected 7–10 days after the last immunization. The red cells were lysed in a hypotonic solution (Gentra Systems). The analysis was performed on the lymphocyte population from 106 PBMCs or 106 splenocytes gating out B 220+ cells. The cells were stained with 0.5 μg of tetramer per sample (20 min at 37°C) followed by mAbs (20 min on ice). They were sorted with a FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed with CELLQUEST software (Becton Dickinson).

IFN-γ Enzyme-Linked Immunospot (ELISPOT). The frequency of peptide-specific IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes was evaluated by ELISPOT (BD Biosciences) as described (14). IFN-γ responses to antigens in L3SEPTL were assessed by mixing effector cells from FP9-L3SEPTL-vaccinated mice with syngeneic splenocytes from unvaccinated mice infected with MVA (multiplicity of infection = 1) expressing one of the six antigens embodied in L3SEPTL. Spots were counted with an AID ELISPOT plate reader (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany).

Statistical Analysis. The comparison of independent means by the Student t test was applied for all experiments.

Results

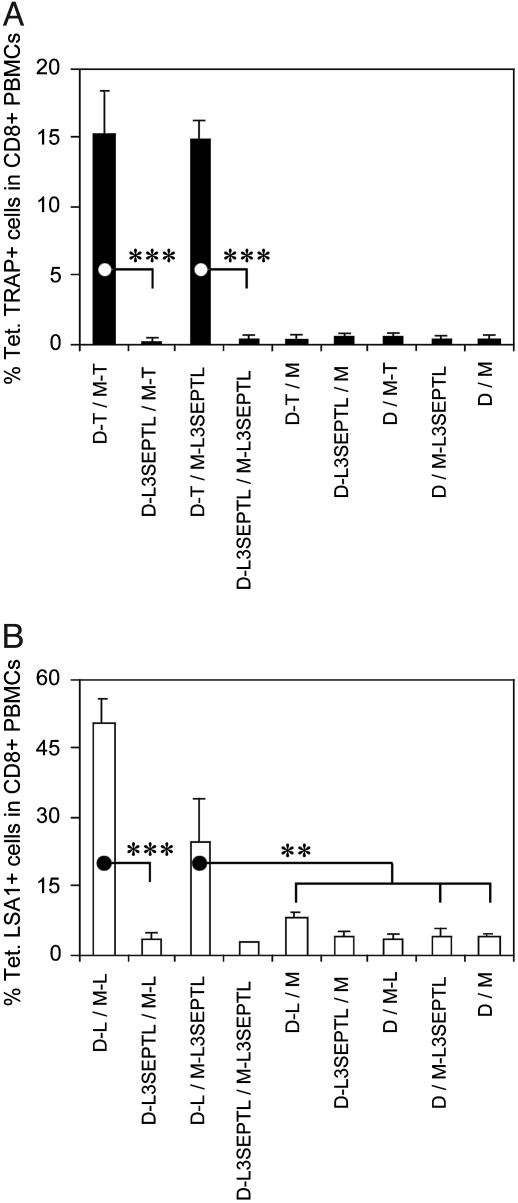

MVA-L3SEPTL Increases CD8+ T Cell Responses Induced by DNA Vaccines. The frequencies of TRAP (Fig. 2A) and LSA1 (Fig. 2B) peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were measured by tetramer staining in blood from mice immunized by the sequential injection of DNA (D) followed by MVA (M) (14) expressing either the single antigens TRAP or LSA1, or the polyprotein L3SEPTL. Priming with DNA-single antigen and boosting with either MVA-single antigen or MVA-L3SEPTL induced a similar number of specific CD8+ T cells. In contrast, immunization with DNA-L3SEPTL did not prime a subsequent boost with either single antigen-expressing MVAs or MVA-L3SEPTL. No significant responses were observed in animals that received vaccination regimes including one or both empty vectors.

Fig. 2.

MVA-L3SEPTL boosts single-antigen DNA-primed anti-TRAP and anti-LSA1 cytotoxic T cell responses. The frequency of peptide-specific CD8+ T cells was measured in blood 5–10 days after the boosting injection by Tet. TRAP (A) or Tet. LSA1 (B) staining in, respectively, C57BL/6 or BALB/c inbred strains of mice. The animals were immunized according to the schedule described in Materials and Methods. DNA and MVA vectors without antigen-coding inserts are denoted D and M, respectively. The results are shown as the percentage of tetramer-positive cells of CD8+ T cells + SE (in B, n = 1 in D-L3SEPTL/M-L3SEPTL, n = 2 in D-L3SEPTL/M-L and D/M-L3SEPTL, n = 3inall other groups in A and B). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed).

Polyprotein-Expressing DNA Vaccines Fail To Prime a Strong Cellular Response. We analyzed the potential of DNA vaccines expressing polyproteins of different sizes to induce LSA1 peptide-specific IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. 3). As observed in tetramer analysis (Fig. 2), MVA-L3SEPTL and MVA-LSA1 equally amplified DNA-LSA1-induced CD8+ T cell responses. The magnitude of the IFN-γ response was markedly reduced in the groups that received the DNAs encoding the polyproteins EPTL, SEPTL, or L3SEPTL.

Fig. 3.

The magnitude of the LSA1 peptide-specific IFN-γ response is reduced in regimes employing DNA-polyprotein priming. BALB/c mice were immunized as described in Materials and Methods. The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific splenocytes secreting IFN-γ 2 weeks after the boosting injection after a short term ex vivo stimulation with LSA1 peptide (filled bars) vs. no peptide (open bars) was measured by ELISPOT. The results are shown as IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFCs) per million splenocytes + SEs (n = 3). **, P < 0.01 (two-tailed).

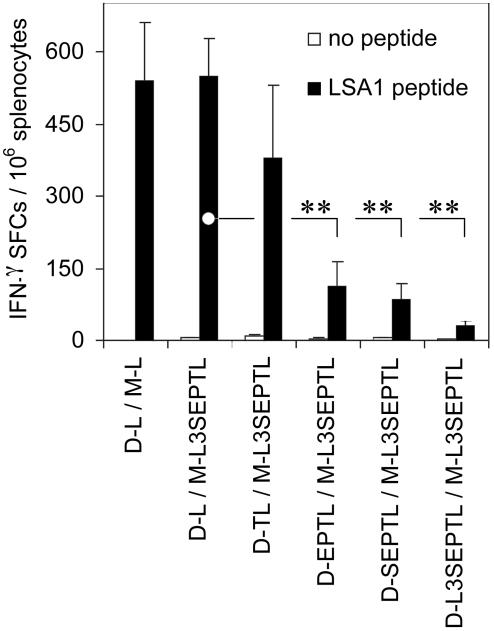

Immunization by Sequential Injection of Heterologous Poxviruses Expressing L3SEPTL Induces a High Frequency of LSA1 Peptide-Specific CD8+ T Cells. L3SEPTL potency was evaluated in a new vaccination regime involving two poxviruses, MVA (M) and the FP9 strain of fowlpox virus (F). The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells was measured in the blood (Fig. 4 Upper) and spleen (Fig. 4 Lower) by tetramer staining. In both compartments, prime boost immunization with L3SEPTL-expressing heterologous viruses stimulated the induction of high frequencies of peptide-specific CD8+ T cells, ranging from 3% to 4% of the total CD8+ population in the blood and 1% in the spleen. Homologous vaccination regimes, in contrast to the heterologous prime boost regimes, did not produce a detectable immune response (13). No responses were detectable after priming with MVA- or FP9-L3SEPTL and boosting with the respective heterologous empty vectors and vice versa. The T cell response elicited against the LSA1 peptide, located close to the C-end (3002–3010) of L3SEPTL (3,240 aa), shows that at least 90% of L3SEPTL is expressed in vivo by the viral vectors MVA and FP9.

Fig. 4.

Immunization regimes with heterologous L3SEPTL-expressing poxviruses generate a peptide-specific CD8+ T cell response. (Upper) Ex vivo tetramer staining of PBMCs 1 week after the boosting injection. (Lower) Ex vivo tetramer staining of splenocytes as for PBMCs. Poxviruses without antigen-coding inserts are annotated M for MVA and F for fowlpox. The results are shown as the percentage of tetramer-positive cells of CD8+ T cells + SE (n = 6 in M-L3SEPTL/F-L3SEPTL and F-L3SEPTL/M-L3SEPTL groups, n = 3 in all other groups). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed).

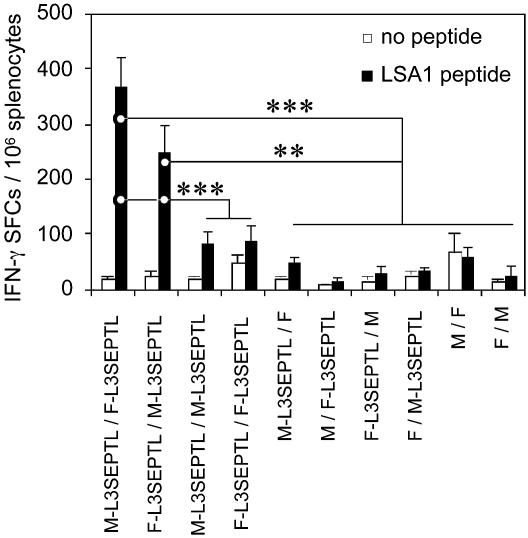

CTLs Induced After Heterologous Prime Boost with Viruses Expressing L3SEPTL Secrete IFN-γ and Are Cytotoxic. The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes was significantly higher in the MVA/FP9 and FP9/MVA prime boost vaccinated groups than in the MVA/MVA and FP9/FP9 groups (Fig. 5). Cytotoxic T cells were induced after heterologous vaccination regimes, but not after homologous regimes (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

CD8+ T cells induced by the vaccination with L3SEPTL-expressing poxviruses secrete IFN-γ and are cytotoxic. The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific splenocytes secreting IFN-γ 1 week after the boosting injection after a short-term ex vivo stimulation with LSA1 peptide (filled bars) vs. no peptide (open bars) was measured by ELISPOT. Poxviruses without antigen-coding inserts are denoted M for MVA and F for fowlpox. The results are shown + SE (n = 6 in M-L3SEPTL/F-L3SEPTL and F-L3SEPTL/M-L3SEPTL groups, n = 3inall other groups). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (two-tailed).

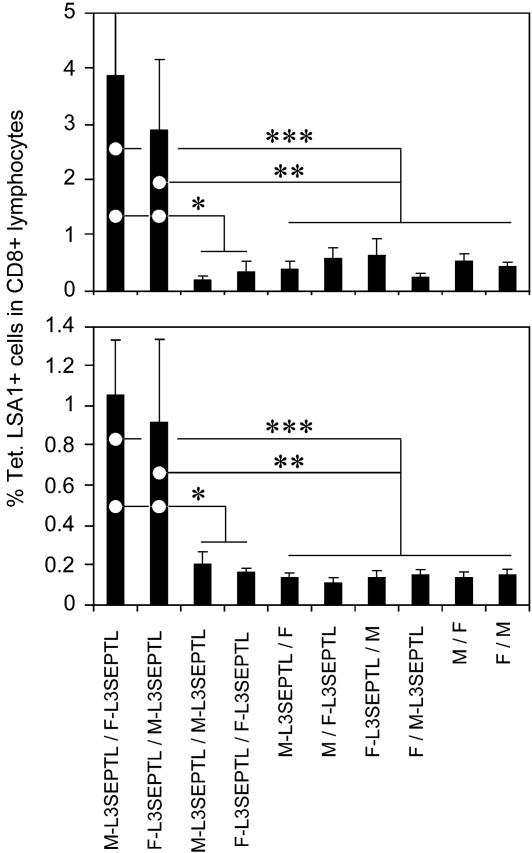

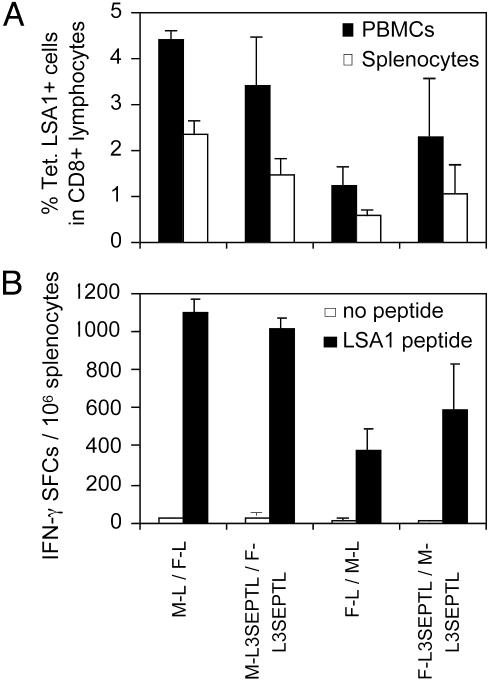

The Length of the Polyprotein L3SEPTL vs. LSA1 Does Not Affect the Anti-LSA1 Peptide Response. The capacity of L3SEPTL and LSA1 in heterologous viral vectors vaccination regimes to induce an anti-LSA1 CD8+ T cell response was compared (Fig. 6). Vaccination with heterologous vectors (MVA/FP9 or FP9/MVA), both expressing either L3SEPTL or LSA1, induced a similar frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells in blood (PBMCs) and spleen (Fig. 6A). This finding was confirmed by the IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. 6B). Therefore, vaccine regime using heterologous poxviruses expressing polyproteins induced CD8+ T cell responses as efficiently as the immunizations with smaller single-antigen constructs.

Fig. 6.

The magnitude and functions of the CD8+ T cell response induced by poxvirus-expressed L3SEPTL are equivalent to those by LSA1. (A) Percentage of Tet. LSA1+ among CD8+ T cells induced by different vaccine regimes 10 days after the boosting injection in spleen (open bars) and blood (filled bars). (B) The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific splenocytes secreting IFN-γ after a short-term ex vivo stimulation with LSA1 peptide (filled bars) vs. no peptide (open bars) was measured by ELISPOT. The results are shown + SE (n = 3).

FP9-L3SEPTL Generates Immune Responses Against Each Antigen Contained in L3SEPTL. IFN-γ responses against each of the six antigens contained in L3SEPTL were detected by ELISPOT with splenocytes from FP9-L3SEPTL-immunized mice stimulated with syngeneic splenocytes infected by single-antigen-expressing MVAs (data not shown). No antigen-specific response was detected in FP9-immunized mice. Nevertheless, mice from both groups had an equivalent anti-vector FP9 response.

In mice receiving a mixture of six DNA vaccines, each encoding a single antigen contained in L3SEPTL, IFN-γ responses specific for different antigen combinations in four inbred strains were expanded after a booster immunization with FP9-L3SEPTL, but not after vaccination regimes including irrelevant DNA or FP9 vaccines (Table 1 and data not shown).

Table 1. IFN-γ response in animals immunized by a mixture of six DNAs each encoding individual antigens from L3SEPTL receiving a booster injection 2 weeks later with FP9-L3SEPTL.

| Splenocytes from unvaccinated mice infected with

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse strain | M-L3 | M-S | M-E | M-P | M-T | M-L |

| BALB/c | — | — | — | + | + | + |

| C57BL/6 | — | — | — | +++ | + | — |

| B10.BR | +++++ | ++ | +++++ | ++ | + | ++++ |

| A/J | +++++ | +++++ | — | + | + | ++++ |

+++++, SFCs measured with antigen encoding MVA-infected targets (SFC exp.) is at least 10-fold higher than SFCs measured with nonrecombinant MVA-infected targets (SFC M); ++++, 8 × SFC M < SFC exp. < 10 × SFC M; +++, 6 × SFC M < SFC exp. < 8 × SFC M; ++, 4 × SFC M < SFC exp. < 6 × SFC M; +, 2 × SFC M < SFC exp. < 4 × SFC M; —, SFC exp. < 2 × SFC M.

Discussion

There is increasing evidence that protective vaccines against various intracellular pathogens will need to induce strong T cell responses against numerous epitopes (19, 38). In murine malaria vaccine models, there is clear evidence that a threshold level of effector T cells is required for protection from sporozoite challenge (14). By far the most potent T cell induction has followed heterologous prime-boost immunization with viral vector boosting.

To address the problems of potency and quality of response, we report two innovative approaches, the use of a hybrid polyprotein containing six malaria antigens, L3SEPTL, and the recently described (R. J. Anderson, unpublished results) combination of an immunogenic attenuated fowlpox virus strain, FP9, and MVA in a heterologous prime-boost immunization regime. We first assessed the immunogenicity of L3SEPTL in a well characterized DNA-prime MVA-boost mouse vaccine model (14). Immunization with plasmid DNA expressing various polyproteins failed to prime a recombinant virus boost. However, priming with DNAs expressing the single antigens contained in L3SEPTL followed by boosting with MVAs expressing the same single antigens or the full-length polyprotein, L3SEPTL, induced strong anti-TRAP- and anti-LSA1-specific CD8+ T cell responses of same magnitude (Figs. 2 and 3).

It therefore seems that the magnitude of the immune response induced by the DNA vaccines seemed to decline with increasing size of the insert. This finding might relate to the high adenine and thymine (AT) content of plasmodial DNA, which is ≈80% AT-rich or to impaired transfection efficiency. The expression of original parasite sequences in mammals may be hampered by the very different optimal codon usages in the two species. However, if codon usage were the main problem accounting for poor immunogenicity of the polyprotein expressed by plasmid DNA, the same difficulty should be observed with viral vector expression. But this was not the case. In in vitro studies, DNA-expressing single antigens, or polyproteins, produced similar levels of protein after transient transfection (data not shown). However, the number of transfected cells with DNA-L3SEPTL (15 kb) was one order of magnitude lower than with shorter constructs including single-antigen constructs and DNA-SEPTL (10 kb) (data not shown) suggesting that, beyond 10 kb, a threshold in transfection efficiency was reached. Another possible explanation of the lower immunogenicity of long plasmid DNA constructs is potential antigenic competition between epitopes in the polyproteins. However, this result is unlikely because the immunogenicity of the poxviruses expressing polyproteins was equivalent to immunization with single-antigen viruses (Fig. 6).

Based on the results with DNA vectors, the vaccine MVAL3SEPTL was retained and combined with a new viral vector, the attenuated fowlpox strain FP9. Other strains of fowlpox have previously been used in heterologous prime boost vaccination regimes (39, 40). A prime boost regime with FP9 and MVA, both expressing L3SEPTL, induced strong CD8+ T cell responses in the blood and spleen (Fig. 4). The frequency of LSA1 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells in blood was lower than after DNA-LSA1/MVA-L3SEPTL regime (compare Figs. 4 Upper and 6B with 2B). This difference could relate to the nature as well as the injection site of the inducing vector, i.v. injection of poxvirus vs. intramuscular injection of DNA. However, the number of IFN-γ-producing cells induced by both vaccine regimes was similar (compare Figs. 5A and 3). The detection of IFN-γ-secreting T cells specific for each of the six antigens in L3SEPTL after vaccination with FP9-L3SEPTL (data not shown and Table 1) confirmed the induction of a T cell immune response of broad specificity. Vaccines containing several antigens will probably induce a more diverse epitope-specific T cell population. This result might be of overall benefit in generating long-lasting protective immunity (12, 14, 15).

The CD8+ T cell response could be boosted only by a heterologous vector. This phenomenon has been observed in numerous other prime boost systems (13, 14, 16). In homologous regimes, the host cellular immune response mounted against the vector probably overcomes T cells specific for the recombinant antigen (E.G.S., unpublished results). The absence of significant T cell cross-reactivity between the MVA and FP9 vectors has recently been demonstrated (R. J. Anderson, unpublished results).

A potential difficulty with the polyprotein strategy could have been low-level expression of this large artificial structure when compared with single antigens. Our data indicate that the low transfection efficiency may well be a problem for plasmid DNA vaccines with very large inserts but that viral vector immunogenicity does not seem to be significantly compromised by greater antigen size. When expressed by the poxvirus vectors, L3SEPTL was able to induce a strong cellular immune response against the CD8+ T cell epitope in LSA1 located close to the C terminus of the polyprotein as well as cellular immune responses disseminated along the whole of L3SEPTL.

There are several potential advantages to a polyprotein immunization strategy: (i) a larger protein will augment the probability of inducing responses to multiple T cell epitopes in immunogenetically diverse human populations; (ii) this result may be particularly valuable when vaccinating individuals in endemic areas who have previously been primed to multiple parasite antigens and in whom the boosting ability of these poxvirus vectors may be important; (iii) the risk of escape mutations being selected should be reduced by a broader induced T cell response; (iv) the large capacity of poxviruses to incorporate foreign DNA should allow assessment of a variety of different antigen combinations as polyproteins, providing a vaccine approach capable of availing of the very large number of pathogen antigens now being identified through whole genome sequencing (41–43); (v) manufacturing of this construct should be simpler and less expensive than a multiplicity of single-antigen vectors. Planned clinical evaluation of these immunogenic constructs should allow these potential advantages to be tested in the field.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Skinner (Institute of Animal Health) for the FP9 virus, Gerald Voss and Denise Doolan for information on peptide epitopes, Vincenzo Cerundolo for providing the expression plasmid for the human β2-microglobulin, and Michael Palmowski for helpful advice for the tetramer construction. E.P. was supported by Grant ERB IC18 CT95 0019 and Marie Curie Training and Mobility of Researchers Research Grant ERB 4001 GT97 2893 (both from the European Commission) and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. A.V.S.H. is a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellow.

Abbreviations: PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; MVA, modified vaccinia virus Ankara; TRAP, thrombospondin-related adhesive protein; LSA, liver stage antigen; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; SFC, spot-forming cell.

References

- 1.Miller, L. H. & Hoffman, S. L. (1998) Nat. Med. 4, 520-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nussenzweig, R. S., Vanderberg, J., Most, H. & Orton, C. (1967) Nature 216, 160-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edelman, R., Hoffman, S. L., Davis, J. R., Beier, M., Sztein, M. B., Losonsky, G., Herrington, D. A., Eddy, H. A., Hollingdale, M. R., Gordon, D. M., et al. (1993) J. Infect. Dis. 168, 1066-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller, L.-H., Baruch, D.-I., Marsh, K. & Doumbo, O.-K. (2002) Nature 415, 673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plebanski, M. & Hill, A. V. (2000) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12, 437-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renggli, J., Hahne, M., Matile, H., Betschart, B., Tschopp, J. & Corradin, G. (1997) Parasite Immunol. 19, 145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss, W. R., Sedegah, M., Beaudoin, R. L., Miller, L. H. & Good, M. F. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 573-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira, A., Schofield, L., Enea, V., Schellekens, H., van-der-Meide, P., Collins, W. E., Nussenzweig, R. S. & Nussenzweig, V. (1986) Science 232, 881-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seguin, M. C., Klotz, F. W., Schneider, I., Weir, J. P., Goodbary, M., Slayter, M., Raney, J. J., Aniagolu, J. U. & Green, S. J. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 353-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doolan, D. L. & Hoffman, S. L. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 884-892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill, A. V., Allsopp, C. E., Kwiatkowski, D., Anstey, N. M., Twumasi, P., Rowe, P. A., Bennett, S., Brewster, D., McMichael, A. J. & Greenwood, B. M. (1991) Nature 352, 595-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seder, R. A. & Hill, A. V. (2000) Nature 406, 793-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider, J., Gilbert, S. C., Hannan, C. M., Degano, P., Prieur, E., Sheu, E. G., Plebanski, M. & Hill, A. V. (1999) Immunol. Rev. 170, 29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider, J., Gilbert, S. C., Blanchard, T. J., Hanke, T., Robson, K. J., Hannan, C. M., Becker, M., Sinden, R., Smith, G. L. & Hill, A. V. (1998) Nat. Med. 4, 397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedegah, M., Jones, T. R., Kaur, M., Hedstrom, R., Hobart, P., Tine, J. A. & Hoffman, S. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7648-7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert, S.-C., Schneider, J., Hannan, C.-M., Hu, J.-T., Plebanski, M., Sinden, R. & Hill, A.-V. S. (2002) Vaccine 20, 1039-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barouch, D.-H., Kunstman, J., Kuroda, M.-J., Schmitz, J.-E., Santra, S., Peyerl, F.-W., Krivulka, G.-R., Beaudry, K., Lifton, M.-A., Gorgone, D.-A., et al. (2002) Nature 415, 335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel, T. U., Friedrich, T. C., O'Connor, D. H., Rehrauer, W., Dodds, E. J., Hickman, H., Hildebrand, W., Sidney, J., Sette, A., Hughes, A., et al. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 11623-11636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doolan, D. L., Sedegah, M., Hedstrom, R. C., Hobart, P., Charoenvit, Y. & Hoffman, S. L. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1739-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doolan, D. L., Hoffman, S. L., Southwood, S., Wentworth, P. A., Sidney, J., Chesnut, R. W., Keogh, E., Appella, E., Nutman, T. B., Lal, A. A., et al. (1997) Immunity 7, 97-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plebanski, M., Aidoo, M., Whittle, H. C. & Hill, A. V. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 2849-2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aidoo, M., Lalvani, A., Gilbert, S. C., Hu, J. T., Daubersies, P., Hurt, N., Whittle, H. C., Druihle, P. & Hill, A. V. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 227-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daubersies, P., Thomas, A. W., Millet, P., Brahimi, K., Langermans, J. A., Ollomo, B., BenMohamed, L., Slierendregt, B., Eling, W., Van-Belkum, A., et al. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 1258-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fidock, D. A., Bottius, E., Brahimi, K., Moelans, I. I., Aikawa, M., Konings, R. N., Certa, U., Olafsson, P., Kaidoh, T., Asavanich, A., et al. (1994) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 64, 219-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hope, I. A., Hall, R., Simmons, D. L., Hyde, J. E. & Scaife, J. G. (1984) Nature 308, 191-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moelans, I. I., Meis, J. F., Kocken, C., Konings, R. N. & Schoenmakers, J. G. (1991) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 45, 193-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robson, K. J., Hall, J. R., Jennings, M. W., Harris, T. J., Marsh, K., Newbold, C. I., Tate, V. E. & Weatherall, D. J. (1988) Nature 335, 79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerin-Marchand, C., Druilhe, P., Galey, B., Londono, A., Patarapotikul, J., Beaudoin, R. L., Dubeaux, C., Tartar, A., Mercereau-Puijalon, O. & Langsley, G. (1987) Nature 329, 164-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidock, D. A., Gras-Masse, H., Lepers, J. P., Brahimi, K., Benmohamed, L., Mellouk, S., Guerin-Marchand, C., Londono, A., Raharimalala, L., Meis, J. F., et al. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 190-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes, D. A., Wollish, W., Nelson, R. G., Leech, J. H. & Petersen, C. (1995) Exp. Parasitol. 81, 79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moelans, I. I., Cohen, J., Marchand, M., Molitor, C., de-Wilde, P., van-Pelt, J. F., Hollingdale, M. R., Roeffen, W. F., Eling, W. M., Atkinson, C. T., et al. (1995) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 72, 179-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sultan, A. A., Thathy, V., Frevert, U., Robson, K. J., Crisanti, A., Nussenzweig, V., Nussenzweig, R. S. & Menard, R. (1997) Cell 90, 511-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wizel, B., Houghten, R. A., Parker, K. C., Coligan, J. E., Church, P., Gordon, D. M., Ballou, W. R. & Hoffman, S. L. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 182, 1435-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Good, M. F. & Doolan, D. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11, 412-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rammensee, H. G., Friede, T. & Stevanoviic, S. (1995) Immunogenetics 41, 178-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackett, M. & Smith, G. L. (1986) J. Gen. Virol. 67, 2067-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunbar, P. R., Ogg, G. S., Chen, J., Rust, N., van-der-Bruggen, P. & Cerundolo, V. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 413-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lauer, G. M., Ouchi, K., Chung, R. T., Nguyen, T. N., Day, C. L., Purkis, D. R., Reiser, M., Kim, A. Y., Lucas, M., Klenerman, P., et al. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 6104-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irvine, K. R., Chamberlain, R. S., Shulman, E. P., Surman, D. R., Rosenberg, S. A. & Restifo, N. P. (1997) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 89, 1595-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson, H. L., Montefiori, D. C., Johnson, R. P., Manson, K. H., Kalish, M. L., Lifson, J. D., Rizvi, T. A., Lu, S., Hu, S. L., Mazzara, G. P., et al. (1999) Nat. Med. 5, 526-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffman, S. L., Rogers, W. O., Carucci, D. J. & Venter, J. C. (1998) Nat. Med. 4, 1351-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardner, M. J., Hall, N., Fung, E., White, O., Berriman, M., Hyman, R. W., Carlton, J. M., Pain, A., Nelson, K. E., Bowman, S., et al. (2002) Nature 419, 498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Florens, L., Washburn, M. P., Raine, J. D., Anthony, R. M., Grainger, M., Haynes, J. D., Moch, J. K., Muster, N., Sacci, J. B., Tabb, D. L., et al. (2002) Nature 419, 520-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]