Abstract

Background

Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) formulations, which produce less systemic exposure compared with oral formulations, are an option for the management of osteoarthritis (OA). However, the overall safety and efficacy of these agents compared with oral or systemic therapy remains controversial.

Methods

Two 12-week, double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, controlled, multicenter studies compared the safety and efficacy profiles of diclofenac topical solution (TDiclo) with oral diclofenac (ODiclo). Each study independently showed that TDiclo had similar efficacy to ODiclo. To compare the safety profiles of TDiclo and ODiclo, a pooled safety analysis was performed for 927 total patients who had radiologically confirmed symptomatic OA of the knee. This pooled analysis included patients treated with TDiclo, containing 45.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and those treated with ODiclo. Safety assessments included monitoring of adverse events (AEs), recording of vital signs, dermatologic evaluation of the study knee, and clinical laboratory evaluation.

Results

AEs occurred in 312 (67.1%) patients using TDiclo versus 298 (64.5%) of those taking ODiclo. The most common AE with TDiclo was dry skin at the application site (24.1% vs 1.9% with ODiclo; P < 0.0001). Fewer gastrointestinal (25.4% vs 39.0%; P < 0.0001) and cardiovascular (1.5% vs 3.5%; P = 0.055) AEs occurred with TDiclo compared with ODiclo. ODiclo was associated with significantly greater increases in liver enzymes and creatinine, and greater decreases in creatinine clearance and hemoglobin (P < 0.001 for all).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that TDiclo represents a useful alternative to oral NSAID therapy in the management of OA, with a more favorable safety profile.

Keywords: diclofenac, gastropathy, oral NSAIDs, osteoarthritis, topical NSAIDs

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac have an established place in the management of osteoarthritis (OA) and related inflammatory disorders.1–3 While unable to modify the disease of OA, NSAIDs are frequently used chronically to manage symptoms. However, the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks associated with nonselective NSAIDs present challenges because OA predominantly affects older patients, who are inherently at greater risk for these events.4 Of particular concern are NSAID-related gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs), or "NSAID gastropathy", which result from decreased prostaglandin synthesis in the gastric lumen, and primarily affect older patients and women.3,5 NSAID gastropathy, which was first recognized in the medical literature in 1986, remains a serious complication for patients seeking relief of OA.6

A recent international, multicenter study of 3293 consecutive candidates for NSAID treatment of OA showed that 86.6% were at increased gastrointestinal risk; 22.3% were considered at high risk for gastrointestinal events. The same study showed that 44.2% of patients were at high cardiovascular risk.4 In addition to increased gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk, NSAIDs are associated with increased risk of hepatic and renal toxicity.7,8

One approach to addressing NSAID toxicity has been the development of topical formulations, which produce less systemic exposure to the drug than oral formulations;9 the use of such formulations is recommended in some current guidelines for the management of OA.1–3 Diclofenac topical solution (PENNSAID®, Mallinckrodt Inc, Hazelwood, MO) is a topical formulation of a 1.5% (w/w) solution of diclofenac sodium in a base containing 45.5% (w/w) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of the signs and symptoms of OA. The DMSO vehicle enhances the penetration of diclofenac through the skin compared with aqueous solutions.8

Several randomized clinical trials have shown that diclofenac topical solution with DMSO is effective and well tolerated in the treatment of OA.10–14 Two trials compared diclofenac topical solution with oral diclofenac for safety and effectiveness.13,14 Both studies evaluated efficacy using the pain and physical function subscales of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Index. Tugwell et al utilized an additional co-primary endpoint, patient global assessment (PGA),13 whereas Simon et al assessed a patient overall health assessment (POHA).14 Details of the efficacy results from each study have been reported previously.13,14 Because the 3 co-primary endpoints were assessed differently across the 2 trials, only the safety data from these trials were pooled and are presented here.

Methods

Study design

Both studies were 12-week randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter trials including patients with primary OA of the knee (Table 1).13,14 The study by Tugwell et al was powered to demonstrate equivalence between active treatments,13 whereas a nonstatistical difference was determined in Simon et al through post hoc analysis.14 Detailed methodologies for both studies have been previously reported.13,14

Table 1.

Summary of study designs

| Tugwell et al13 | Simon et al14 | |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Randomized, prospective, double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled | Randomized, prospective, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-, vehicle-, and active-controlled |

| Setting | 41 outpatient centers in Canada | 40 outpatient centers in Canada; 21 centers in the United States |

| Patients | 622 patients (266 men, 356 women) with symptomatic, primary OA of the knee | 775 patients (295 men, 480 women) with symptomatic, primary OA of the knee |

| Inclusion criteria |

|

|

| Treatment (duration, 12 wk) |

|

|

| Safety assessments | Adverse event monitoring; vital sign measurements; dermatologic examination of study knee; clinical laboratory evaluation | Adverse event monitoring; vital sign measurements; dermatologic examination of study knee; clinical laboratory evaluation; ocular examination |

| Co-primary efficacy endpoints |

Notes:

Using a VAS anchored from none (0 mm) to extreme (100 mm);

Using a VAS anchored from very good (0 mm) to very poor (100 mm);

Using the 5-item WOMAC OA Index pain dimension with each item scored 0–4 and a maximum score of 20. A flare was defined as pain after the washout of prior therapy that attained a score of ≥2 (moderate) on at least one of the 5 items at baseline, or an increase in WOMAC pain total score from screening to baseline of ≥25% and ≥2;

Using a 5-point scale anchored from none (0) to extreme (4);

Using a 5-point scale anchored from very good (0) to very poor (4).

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OA, osteoarthritis; PGA, Patient Global Assessment; POHA, Patient Overall Health Assessment; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; VAS, visual analog scale.

Patients

In the study by Tugwell et al,13 eligible patients included individuals aged 40–85 years with primary OA of the knee defined as: 1) standard radiographic criteria for OA based on recent (within 3 months) examination,15 and 2) at least mild symptoms of OA based on minimum scores in predetermined subscales of the WOMAC Index assessment tool (pain, ≥125 mm; physical function, ≥425 mm)16 and PGA score ≥25 mm.

In the study by Simon et al,14 eligible patients were those aged 40–85 years with primary OA of the defined as 1) standard radiographic criteria for OA based on recent (≤3 months) examination, 2) pain with regular use of NSAID or other analgesic, and 3) flare of pain and minimum Likert pain score of 8 (40 on a scale normalized to 0–100) at baseline, following washout of previous medication. A flare was defined as an increase in total Likert pain score of 25% and ≥2, and a score of at least moderate on 1 or more of the 5 items in the WOMAC pain subscale.

In both studies, exclusion criteria were secondary arthritis; previous major surgery; sensitivity to study treatment drugs or other NSAIDs; severe cardiac, renal, hepatic, or other systemic disease; and history of drug or alcohol abuse.

Treatment

Patients in the Tugwell et al study (n = 622) were treated with diclofenac topical solution (1.5% w/w diclofenac sodium, 45.5% w/w DMSO, and other excipients) plus oral placebo capsules, or oral diclofenac 50-mg capsules plus topical placebo solution (2.3% w/w DMSO, no diclofenac). Patients applied 50 drops of study solution (approximately 1.55 mL) to the affected knee and took 1 study capsule, 3 times daily.13

In Simon et al, patients (n = 775) received one of 5 treatments: 1) diclofenac topical solution (1.5% w/w diclofenac sodium, 45.5% w/w DMSO, plus other excipients) plus oral placebo tablets; 2) vehicle solution (45.5% w/w DMSO, no diclofenac) plus oral placebo tablets; 3) topical placebo solution (2.3% w/w DMSO, no diclofenac) plus oral placebo tablets; 4) placebo solution plus oral diclofenac tablets (100 mg, slow-release); or 5) diclofenac topical solution plus oral diclofenac tablets. Patients applied 40 drops of solution (approximately 1.2 mL) to the affected knee 4 times daily and took 1study tablet daily.14

Safety and efficacy assessments

Safety assessments in both studies included monitoring of AEs, recording of vital signs, dermatologic examination of the study knee (in patients in whom both knees were affected by OA, only the knee with the greater pain score at baseline was assessed), and clinical laboratory evaluation (hematology, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis).13,14 In addition, patients in the study by Simon et al underwent ocular examination (visual acuity testing, slit lamp examination, and lens assessment) at baseline and the final visit.14

The 3 co-primary efficacy measures in both studies were changes from baseline in scores for the WOMAC pain and physical function subscales, and patient-evaluated efficacy (PGA in the Tugwell et al study13 and POHA in the Simon et al study14). Details on these co-primary efficacy assessments, as well as secondary efficacy measures, have been previously published.13,14

Statistical analysis

Differences in baseline demographic characteristics and the incidence of AEs between patients receiving diclofenac topical solution or oral diclofenac were analyzed by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, or by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment as main effect for continuous variables. Descriptive statistics were provided for every safety variable, including mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum for continuous variables (eg, vital signs), and incidence rate for noncontinuous variables (eg, AEs). Where statistical tests were performed, they were 2-sided at the 5% level of significance (P < 0.05).

AEs were evaluated for statistical significance by system organ class (SOC). An AE was evaluated individually within a specific SOC if it showed a significant difference in occurrence of AEs between treatment groups. Additionally, an a priori analysis of individual AEs was initiated for several SOCs despite significance, including cardiovascular disorders (hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death), gastrointestinal disorders (abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, halitosis, and body odor), and application-site conditions (contact dermatitis, dry skin, paresthesia, rash, and pruritus). These were analyzed due to their importance in oral and topical NSAID administration. If a category was statistically significant as a whole, the specific AEs within the group were evaluated for significance.

Results

A total of 927 patients was analyzed; 465 received diclofenac topical solution and 462 received oral diclofenac. Baseline demographic characteristics for each study have been reported previously.13,14 There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups.

Safety and tolerability

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 67.1% of patients receiving diclofenac topical solution and 64.5% taking oral diclofenac. The most common events occurring with diclofenac topical solution that occurred at a greater rate than with oral diclofenac were application site-related events. AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in 18.5% of patients receiving diclofenac topical solution and 21.0% receiving oral diclofenac. The most common AEs leading to discontinuation in the diclofenac topical solution group were application site-related events, whereas gastrointestinal disorders were the most common cause of discontinuation in the oral diclofenac group. Overall incidence of AEs for each SOC and incidence of individual treatment-emergent events and discontinuations are described in detail for each AE category, as well as AEs related to liver and renal function, vital signs, and musculoskeletal disorders.

Gastrointestinal adverse events

Gastrointestinal AEs were significantly more common with oral diclofenac versus diclofenac topical solution (39.0% vs 25.4%, P < 0.0001). The most common gastrointestinal AEs were dyspepsia (18.4% vs 11.0%, P = 0.001), diarrhea (13.4% vs 6.5%, P < 0.001), abdominal distension (10.6% vs 6.0%, P = 0.01), and abdominal pain upper (12.1% vs 5.6%, P < 0.001). Nonsignificant differences between groups were also shown for nausea (9.3% vs 5.2%), constipation (7.4% vs 5.2%) and abdominal pain lower (5.4% vs 3.9%) (Table 2). A total of 67 patients (14.5%) receiving oral diclofenac and 27 patients (5.8%) receiving diclofenac topical solution discontinued because of a gastrointestinal-related AEs (P < 0.0001). One serious gastrointestinal AE was reported: gastric ulcer hemorrhage in 1 patient (0.2%) receiving oral diclofenac (Table 3).

Table 2.

Incidence of treatment-emergent gastrointestinal adverse events occurring in >1 patient in either treatment group

| Adverse event, n (%) | Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465) | Oral diclofenac (n = 462) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any gastrointestinal disorder | 118 (25.4) | 180 (39.0) | <0.0001* |

| Dyspepsia | 51 (11.0) | 85 (18.4) | 0.001* |

| Diarrhea | 30 (6.5) | 62 (13.4) | 0.0004* |

| Abdominal distension | 28 (6.0) | 49 (10.6) | 0.01* |

| Abdominal pain upper | 26 (5.6) | 56 (12.1) | 0.0005* |

| Constipation | 24 (5.2) | 34 (7.4) | 0.17* |

| Nausea | 24 (5.2) | 43 (9.3) | 0.15* |

| Abdominal pain lower | 18 (3.9) | 25 (5.4) | 0.26* |

| Flatulence | 8 (1.7) | 9 (1.9) | 0.80* |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (1.1) | 12 (2.6) | 0.08* |

| Feces discolored | 5 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 0.75* |

| Vomiting | 5 (1.1) | 9 (1.9) | 0.28* |

| Breath odor | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0.37† |

| Abdominal discomfort | 3 (0.6) | 8 (1.7) | 0.13* |

| Dry mouth | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.62† |

| Eructation | 3 (0.6) | 4 (0.9) | 0.72† |

| Epigastric discomfort | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.62† |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.25† |

| Hematochezia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.25† |

| Toothache | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.25† |

Notes:

From Chi-square test;

From Fisher’s exact test.

Table 3.

Incidence of serious adverse events

| Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465)

|

Oral diclofenac (n = 462)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | Events, n | Patients, n (%) | Events, n | |

| Any serious adverse events | 1 (0.2) | 1 | 6 (1.3) | 8* |

| Vascular disorders | ||||

| Arteriosclerosis | 1 (0.2) | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 |

| Cardiac disorders | ||||

| Overall | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 3 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

| Gastric ulcer hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | ||||

| Postprocedural hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Investigations | ||||

| Liver function test abnormal | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||

| Synovial cyst | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

Notes:

From Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.069.

Cardiovascular adverse events

The incidence of cardiovascular AEs was low overall but was numerically higher in the oral diclofenac group, showing a trend towards significance (3.5% vs 1.5%, P = 0.055). Differences between groups for all individual events (eg, hypertension, arrhythmia, and myocardial infarction) were nonsignificant and occurred in <2% of individuals in either treatment group (Table 4). Four patients (0.9%) taking oral diclofenac and 1 patient (0.2%) taking diclofenac topical solution discontinued the study due to a cardiovascular AE (P = 0.22). Three serious cardiovascular AEs were reported in 2 patients (0.4%) taking oral diclofenac: myocardial infarction (n = 2) and coronary artery disease (n = 1) (Table 3). One of these patients died from stroke following the presentation of the cardiac event. One case of arteriosclerosis was observed in 1 patient receiving diclofenac topical solution, deemed as unrelated to treatment.

Table 4.

Incidence of treatment-emergent cardiovascular events

| Adverse event, n (%) | Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465) | Oral diclofenac (n = 462) |

|---|---|---|

| Any cardiovascular-related adverse event | 7 (1.5) | 16 (3.5)* |

| Vascular disorders | ||

| Overall | 6 (1.3) | 10 (2.2) |

| Hypertension | 5 (1.1) | 8 (1.7) |

| Arteriosclerosis | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Varicose veins | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hot flush | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Cardiac disorders | ||

| Overall | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.3) |

| Angina pectoris | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Angina unstable | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Arrhythmia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Palpitations | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Supraventricular extrasystoles | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

Notes:

From Chi-square test, P = 0.055.

Application site-related adverse events

Application site-related AEs were significantly more common in patients receiving diclofenac topical solution than those receiving oral diclofenac (29.0% vs 6.1%, P < 0.0001). Dry skin (24.1% vs 1.9%, P < 0.0001), pruritus (4.9% vs 1.9%, P = 0.01), and contact dermatitis (4.3% vs 0.6%, P < 0.001) were most common (Table 5). There was no difference between groups in paresthesia (both 1.3%). More individuals treated with diclofenac topical solution (8.8%) versus those receiving oral diclofenac (0.2%) discontinued due to an application-site reaction. There were no serious application site-related AEs in either group.

Table 5.

Incidence of treatment-emergent application site-related adverse events

| Adverse event, n (%) | Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465) | Oral diclofenac (n = 462) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any application site-related adverse event | 135 (29.0) | 28 (6.1) | <0.0001* |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||

| Overall | 134 (28.8) | 23 (5.0) | <0.0001* |

| Dry skin | 112 (24.1) | 9 (1.9) | <0.0001* |

| Pruritus | 23 (4.9) | 9 (1.9) | 0.01† |

| Dermatitis contact | 20 (4.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0.0004† |

| Rash | 10 (2.2) | 6 (1.3) | 0.32 |

| Urticaria | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | >0.99 |

| Nervous system disorders | |||

| Paresthesia | 6 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) | 1.0 |

Notes:

From Chi-square test;

From Fisher’s exact test.

Liver and renal function

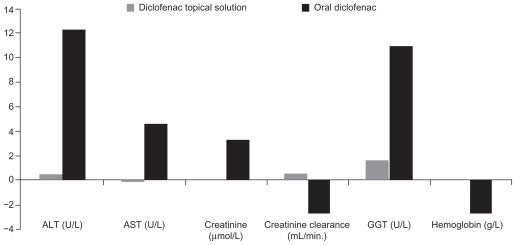

Compared with diclofenac topical solution, oral diclofenac was associated with significantly greater increases in liver enzymes and creatinine, and greater decreases in creatinine clearance and hemoglobin (Figure 1). At baseline, there were no significant differences in the incidence of abnormal liver enzyme concentrations between groups. However, at the end of the study, patients receiving oral diclofenac showed a significantly higher incidence of abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (22.2% vs 10.4%, P < 0.0001), aspartate aminotransferase (14.6% vs 7.0%, P < 0.001), and γ-glutamyltransferase (33.4% vs 21.1%, P < 0.0001). Additionally, there was a higher incidence of clinically significant elevations in ALT with oral diclofenac (4.1% vs 1.2%, P < 0.01) (Table 6). Nonsignificant differences between groups were shown for increases in serum creatinine (10.3% vs 8.2%, P = 0.30), as well as decreases in creatinine clearance (84.2% vs 81.3%, P = 0.36) and hemoglobin (9.8% vs 8.2%, P = 0.42) in the oral diclofenac and diclofenac topical solution groups, respectively. Discontinuation due to abnormal liver and renal function test results occurred in 6 patients: 5 (1.1%) receiving oral diclofenac and 1 (0.2%) treated with diclofenac topical solution.

Figure 1.

Mean changes in clinical chemistry measurements in patients receiving topical diclofenac solution or oral diclofenac.

Note: P < 0.0001 for all treatment differences except for creatinine clearance, where P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase.

Table 6.

Incidence of abnormal liver enzymes

| Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465) | Oral diclofenac (n = 462) |

P value

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Any abnormality, n (%) | |||

| ALT | |||

| Baseline | 50 (10.9) | 43 (9.5) | 0.46* |

| End of study | 44 (10.4) | 93 (22.2) | <0.0001* |

| AST | |||

| Baseline | 40 (8.7) | 29 (6.4) | 0.18* |

| End of study | 30 (7.0) | 61 (14.6) | 0.0004* |

| GGT | |||

| Baseline | 108 (23.6) | 106 (23.2) | 0.90* |

| End of study | 90 (21.1) | 140 (33.4) | <0.0001* |

| Clinically significant abnormalities, n (%) | |||

| ALT | |||

| Baseline | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | >0.99† |

| End of study | 5 (1.2) | 17 (4.1) | 0.009* |

| AST | |||

| Baseline | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0.62† |

| End of study | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.4) | 0.34† |

| GGT | |||

| Baseline | 14 (3.1) | 10 (2.2) | 0.41* |

| End of study | 18 (4.2) | 22 (5.3) | 0.48* |

Notes:

From Chi-square test;

From Fisher’s exact test.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase.

Vital signs

There were no significant differences between treatments in changes in mean blood pressure, heart rate, or respiratory rate. Patients treated with diclofenac topical solution had a mean (SD) change in systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP) of −0.11 (12.55)/−0.27 (8.31) mm Hg versus a change of 0.34 (14.93)/−0.15 (9.20) mm Hg in patients receiving oral diclofenac. However, at the end of the study, the proportion of patients with abnormally elevated diastolic blood pressure values (≥90 mm Hg) was significantly greater for oral diclofenac versus diclofenac topical solution (44.3% vs 34.9%, P < 0.01); there was no significant difference in the incidence of elevated systolic blood pressure values (≥140 mm Hg) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Incidence of abnormally high blood pressure values

| Patients with abnormal values

|

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac topical solution (n = 465) | Oral diclofenac (n = 462) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure, n (%) | |||

| Baseline | 178 (38.5) | 206 (44.7) | 0.058* |

| End of study | 134 (34.9) | 167 (44.3) | 0.008* |

| Systolic blood pressure, n (%) | |||

| Baseline | 353 (76.2) | 356 (77.2) | 0.72* |

| End of study | 293 (76.3) | 289 (76.7) | 0.91* |

Note:

From Chi-square test.

Musculoskeletal

The most commonly reported musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders were back pain, which occurred in a slightly higher proportion of patients treated with diclofenac topical solution (4.7%) versus those taking oral diclofenac (3.2%), and arthralgia, which occurred in slightly more patients taking oral diclofenac (4.8% vs 4.7%). The only nervous system disorder reported in >5% of patients in either group was headache (10.0% with oral diclofenac vs 8.8% with diclofenac topical solution). Thirteen patients in the diclofenac topical solution group (2.8%) discontinued due to musculoskeletal or connective tissue disorders, versus 6 patients taking oral diclofenac (1.3%). One musculoskeletal AE attributed to oral diclofenac, a synovial cyst, was considered serious.

Discussion

The results in this pooled analysis confirm that NSAIDrelated AEs remain a serious issue for OA patients. For example, NSAID gastropathy, nearly a quarter century after its identification, persists in the elderly who are at high risk for gastrointestinal events. Although two classes of medications, proton pump inhibitors and prostaglandins (misoprostol), have shown promise, treating NSAID gastropathy is problematic due to its asymptomatic nature and adherence challenges.6,17

Diclofenac topical solution was associated with a lower incidence of gastrointestinal AEs than the oral formulation. Dyspepsia, diarrhea, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, and nausea – all elements of NSAID gastropathy – were reported significantly more frequently with oral diclofenac treatment, including one serious gastrointestinal bleeding event. In the current analysis, the incidence of peptic ulceration or gastrointestinal hemorrhage was low, and such events were confined to patients receiving oral diclofenac. The incidence rates of gastrointestinal AEs in patients taking oral diclofenac in this pooled analysis are consistent with previous studies (up to 48%); as well as discontinuation rates (up to 16%).18

While cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective NSAIDs are known for their reduced gastrointestinal effects, recent studies demonstrated significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with these agents. This increased risk was first seen in rofecoxib during the VIGOR trial, which showed a significant increase in myocardial infarction compared with the nonselective NSAID naproxen (0.4% vs 0.1%, P < 0.05).19 These results were confirmed during the Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on VIOXX (APPROVe) trial, which showed a significant increase in cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, with rofecoxib compared with placebo (2.4% vs 0.9%; hazard ratio 2.80 [95% CI 1.44–5.45]).20 These and other data led to withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market in 2005. One recent meta-analysis confirmed that rofecoxib is associated with increased cardiovascular events (relative risk 1.24 [95% CI 1.05–1.46]) without evidence of similar increased risk with other COX-2 selective agents such as celecoxib (relative risk 0.99 [95% CI 0.85–1.16]).21

The most common AEs with diclofenac topical solution in this analysis were application-site reactions. The incidence of application-site reactions in this study (29.0%) was greater than in recent studies of diclofenac sodium gel (5%–6% incidence)22,23 but was similar to that observed in previous placebo-controlled trials of diclofenac topical solution.10–12 In the Simon et al study,14 which included a DMSO vehicle group, dry skin reaction incidence was similar between patients receiving the vehicle alone (11.2%) and diclofenac topical solution (18.2%), suggesting that these reactions are attributable to the vehicle rather than the active drug. DMSO may produce skin dryness by dissolving lipids on the skin surface.14 Although the effects of emollient use on application site-related AEs were not evaluated in the current analysis, it would likely help alleviate these reactions in clinical practice.

Abnormalities in hepatic and renal function are another concern with long-term oral NSAID therapy. At the end of the study, the incidence of abnormal liver enzyme elevations, particularly clinically significant elevations in ALT, was significantly higher in patients who received oral diclofenac than in those who were treated with diclofenac topical solution. Diclofenac topical solution did not show similar increases, which is likely due to reduced systemic levels with topical NSAIDs. Both groups, however, exhibited increased serum creatinine and decreased creatinine clearance, though the differences were not significant. These results may be related to the study populations, which had mean age of >60 years. Decreased liver metabolism and renal excretion are 2 pharmacologic attributes that can change as patients age, resulting in decreased oxidation in the liver and decreased renal excretion.24

The improved safety and tolerability profile of diclofenac topical solution, taken in context with similar improvements in efficacy versus oral diclofenac, highlight the potential impact of diclofenac topical solution in the overall treatment of OA. Nonselective oral NSAIDs, although generally well tolerated, are associated with increased risk of serious gastrointestinal and cardiovascular AEs.4 COX-2 inhibitors are associated with less gastrointestinal risk (although this risk is not completely mitigated) but greater cardiovascular risk compared with nonselective NSAIDs.4 US clinical guidelines recommend that patients be selected carefully after evaluating the risk of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal events, using particular caution in older patients.24 Those at increased gastrointestinal risk should receive a gastroprotective agent such as a proton pump inhibitor in conjunction with oral nonselective NSAID therapy or be treated with COX-2 selective NSAIDs in the absence of pre-existing cardiovascular risk. Because OA most commonly occurs in older individuals, topical therapy is appropriate in these individuals, who have an inherently higher risk.24

In 2008, the United Kingdom-based National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) went a step further by recommending that topical NSAIDs, along with acetaminophen, should be the first pharmacologic options in the management of OA pain prior to the use of opioid analgesics, oral NSAIDS, and COX-2 inhibitors.3 US guidelines, such as the American College of Rheumatology guidelines (updated in 2000) and American Geriatrics Society guidelines (updated in 2009) have yet to include topical NSAIDs as first-line treatment.24 As more information concerning the safety and overall efficacy of topical NSAIDs is published and medical societies update their existing recommendations, health organizations will have new opportunities to evaluate these data.

Although efficacy data were not pooled for this analysis, in both current studies the efficacy of diclofenac topical solution was either equivalent or not significantly different from that of oral diclofenac. In Tugwell et al, the 95% confidence intervals for the treatment differences in WOMAC pain, WOMAC physical function, and PGA between diclofenac topical solution and oral diclofenac were all within the pre-defined equivalence ranges.13 In Simon et al, diclofenac topical solution produced significantly greater improvements in the co-primary endpoints of WOMAC pain, WOMAC physical function, and POHA compared with placebo or vehicle treatment, and was not significantly different from oral diclofenac.14

Limitations

While the information presented in this pooled analysis may be informative for guiding the overall management in OA, there were several limitations to consider. These trials were conducted over a period of 12 weeks, which may not be long enough to determine significant differences in AEs associated with long-term NSAID therapy, particularly cardiovascular AEs. Furthermore, these trials limited co-morbid conditions, concomitant medications, and the maximum doses of both oral diclofenac and diclofenac topical solution, all of which may affect the generalizability of these results. Additionally, since the 3 co-primary endpoints in both trials were assessed using different scales (visual analog pain scale for Tugwell et al,13 Likert scale for Simon et al14) it is not possible to pool the results from the WOMAC pain and physical function scales. Hence, only the safety data from these trials were pooled and reported here. Larger head-to-head, multicenter trials of much longer duration and that include a greater number of older patients are needed to adequately establish differences in long-term efficacy and safety between topical and oral formulations of diclofenac. It is possible that the results of the pooled analysis underestimate the comparative clinical benefit of topical diclofenac solution over oral diclofenac for reducing the risks of serious gastrointestinal and cardiovascular AEs, especially for long-term treatment of OA in an elderly patient population of ≥75 years of age.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pooled safety data from these 2 randomized trials demonstrated that diclofenac topical solution had a better tolerability profile than oral diclofenac, in terms of gastrointestinal AEs and changes in clinical laboratory variables. Because both studies showed that diclofenac topical solution was comparable in efficacy to oral diclofenac, these findings suggest that topical administration represents a useful alternative to oral treatment in the management of OA, especially in elderly patients and those at increased risk for serious gastrointestinal adverse events.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Both Dr Roth and Dr Fuller contributed to the concept of this subanalysis, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Dr Roth is a current stakeholder within Transdel Pharmaceuticals. Dr Roth serves as a consultant and speaker for Covidien. Dr Fuller is an employee of Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien Company, the distributor of PENNSAID® (diclofenac sodium topical solution 1.5% w/w) in the USA.

Sponsor’s role

Editorial and writing support for this article was provided by Michael Shaw, PhD, and Synchrony Medical LLC, West Chester, PA. Funding for this support was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien Company. The sponsor reviewed the manuscript for medical accuracy.

Data analysis

Dr Roth asserts that he had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Data analysis was provided by David A. Schwab, PhD, PSF Solutions, Downingtown, PA. Funding for this analysis was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, a Covidien Company, but no Covidien employees were involved in the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidencebased, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(2):137–162. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(4):476–499. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Osteoarthritis: National clinical guideline for care and management in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. [Accessed May 5, 2010]. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG059FullGuideline.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanas A, Tornero J, Zamorano JL. Assessment of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk in patients with osteoarthritis who require NSAIDs: the LOGICA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(8):1453–1458. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth SH. NSAID gastropathy. A new understanding. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(15):1623–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth SH. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. We started it – can we stop it. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146(6):1075–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teoh NC, Farrell GC. Hepatotoxicity associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7(2):401–413. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelton A. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. Am J Med. 1999;106(5B):13S–24S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moen MD. Topical diclofenac solution. Drugs. 2009;69(18):2621–2632. doi: 10.2165/11202850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baer PA, Thomas LM, Shainhouse Z. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with a topical diclofenac solution: a randomised controlled, 6-week trial [ISRCTN53366886] BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bookman AA, Williams KS, Shainhouse JZ. Effect of a topical diclofenac solution for relieving symptoms of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2004;171(4):333–338. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth SH, Shainhouse JZ. Efficacy and safety of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) in the treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(18):2017–2023. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tugwell PS, Wells GA, Shainhouse JZ. Equivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(10):2002–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis. Pain. 2009;143(3):238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellamy N. WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index User’s Guide III. London, Ontario: London Health Sciences Centre; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman RD, Hochberg M, Murphy WA, Jr, et al. Atlas of individual radiological features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1995;3 (Suppl A):3–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth SH. Arthritis therapy: Back to the future (editorial) Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(1):36–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emery P, Zeidler H, Kvien TK, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac in long-term management of rheumatoid arthritis: randomised double-blind comparison. Lancet. 1999;354(9196):2106–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(21):1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lévesque LE, Brophy JM, Zhang B. The risk for myocardial infarction with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a population study of elderly adults. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):481–489. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barthel HR, Haselwood D, Longley S, 3rd, et al. Randomized controlled trial of diclofenac sodium gel in knee osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baraf HS, Gold MS, Clark MB, et al. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium 1% gel in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38(2):19–28. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.06.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]