Abstract

Genomic integrity often is compromised in tumor cells, as illustrated by genetic alterations leading to loss of heterozygosity (LOH). One mechanism of LOH is mitotic crossover recombination between homologous chromosomes, potentially initiated by a double-strand break (DSB). To examine LOH associated with DSB-induced interhomolog recombination, we analyzed recombination events using a reporter in mouse embryonic stem cells derived from F1 hybrid embryos. In this study, we were able to identify LOH events although they occur only rarely in wild-type cells (≤2.5%). The low frequency of LOH during interhomolog recombination suggests that crossing over is rare in wild-type cells. Candidate factors that may suppress crossovers include the RecQ helicase deficient in Bloom syndrome cells (BLM), which is part of a complex that dissolves recombination intermediates. We analyzed interhomolog recombination in BLM-deficient cells and found that, although interhomolog recombination is slightly decreased in the absence of BLM, LOH is increased by fivefold or more, implying significantly increased interhomolog crossing over. These events frequently are associated with a second homologous recombination event, which may be related to the mitotic bivalent structure and/or the cell-cycle stage at which the initiating DSB occurs.

Keywords: double-strand break repair, gene conversion

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is a major mechanism for uncovering mutations in tumor-suppressor genes. Examination of tumor cells and model studies in cell lines have established several mechanisms of LOH, including chromosome loss/duplication (uniparental disomy), mitotic recombination between homologous chromosomes, and gross chromosomal rearrangement as a result of genome-wide chromosomal instability (1–4). LOH caused by homologous recombination (HR) can arise from crossing over between homologous chromosomes, followed by segregation of crossover (CO) chromatids to separate daughter cells (CO-LOH). In this way, the entire chromosome arm distal to the point of crossing over is homozygozed for genetic information. This process contrasts with interhomolog noncrossover (NCO) events during which gene conversion gives rise to only small regions of LOH (5). Chromosomal double-strand breaks (DSBs) may be initiating lesions for CO-LOH, because they induce interhomolog crossing over in meiotic cells (reviewed in ref. 6). Although DSB-induced crossing over is clearly necessary during the specialized first meiotic division (6), a role for interhomolog crossing over in mitotic cells is uncertain.

DSBs induce mitotic interhomolog HR in mammalian cells (7), but CO-LOH occurs infrequently during DSB repair (5, 8), suggesting that factors actively suppress crossing over. Candidate factors include the RecQ helicase deficient in cells from Bloom syndrome patients (BLM) (9). Consistent with this notion, levels of spontaneous intersister COs, i.e., sister-chromatid exchanges, are elevated in both human and mouse BLM-deficient cells (10, 11), as is the frequency of spontaneous LOH (9, 11–13). CO suppression is supported biochemically because BLM, together with TOPIIIα and RMI1, migrates Holliday junctions to promote their dissolution (14). Genetic evidence in both yeast and Drosophila support a role for the respective BLM homologs (Sgs1 and MUS309, respectively) in suppressing interhomolog COs at DNA lesions (15–17). A recent study in human cells is consistent with a similar role of mammalian Blm, although crossing over could not be distinguished from other repair pathways (18).

To determine mechanisms that promote LOH from interhomolog HR, we induced a DSB in one homolog of chromosome 14 in a mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell line derived from F1 hybrid embryos. Using polymorphisms along the chromosome to screen for LOH, we found that a DSB can induce LOH, although rarely, in wild-type cells (≤2.5% of interhomolog HR events). Overall rates of interhomolog HR are not increased in BLM-deficient cells; however, we found that rates of LOH are substantially elevated with BLM deficiency. Molecular analysis of LOH events demonstrates they are best explained by an interhomolog CO mechanism (CO-LOH) and that a large majority of such CO-LOH events are associated with a second HR event, an NCO on the other chromatid. We discuss our findings in relation to the mitotic bivalent structure and the cell-cycle stage of DSB formation associated with interhomolog COs.

Results

S/P Reporter Measures Interhomolog Recombination.

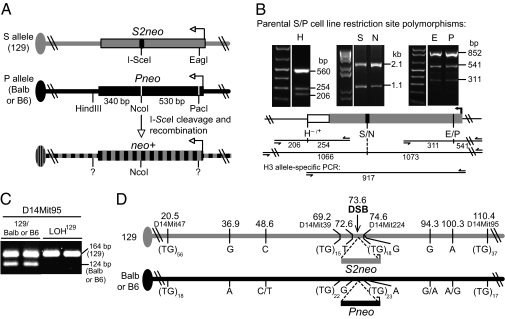

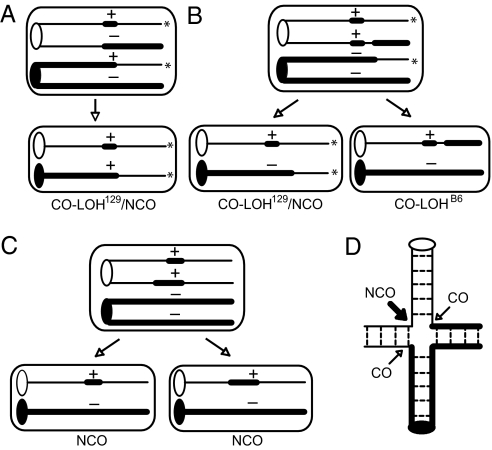

To examine LOH arising from DSB-induced mitotic recombination, we used the previously described S/P reporter system (Fig. 1A) (5). This system takes advantage of an ES cell line derived from F1 hybrid mouse embryos in which one parental set of chromosomes is from the 129/Sv (129) strain (the S allele), and the other is from the BALB/c (Balb) strain (the P allele). Two nonfunctional neo genes were sequentially targeted at the same allelic position of both chromosome 14 homologs in this cell line (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). S2neo, which contains an I-SceI endonuclease site disrupting the neo gene, was targeted to the 129-derived copy of chromosome 14 (S allele), and Pneo, which contains a disrupting PacI restriction site insertion in the 5′ end of the gene, was targeted to the Balb-derived chromosome 14 (P allele). S2neo contains a wild-type neo sequence at the position of the PacI site in Pneo (in this case, an EagI site), and Pneo contains a wild-type sequence at the position of the I-SceI site in S2neo (in this case, an NcoI site). With I-SceI expression in the S/P cells, a DSB generated in the S allele can be repaired by several mechanisms, but only interhomolog recombination with the P allele—either an NCO or CO event—gives rise to neo+ recombinants (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2). Examining a limited number of recombinants, we previously found that neo+ recombinants are NCOs in which the I-SceI site in S2neo is converted to the NcoI site of Pneo without exchange of flanking markers, thus restricting LOH to the region around the DSB (5; Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

S/P reporter to detect LOH associated with interhomolog recombination. (A) The S/P reporter contains two defective neo genes at the same allelic position on chromosome 14 in mouse ES cells. Expression of I-SceI results in a DSB in S2neo that can be repaired via interhomolog recombination using Pneo as a template for repair, resulting in a neo+ gene. (B) Restriction site polymorphisms detect gene conversion at or near the DSB. In the S/P parental line, each polymorphism is heterozygous, as demonstrated by partial cleavage of PCR products that amplify both alleles. Primer positions are indicated (arrows), with the expected cleavage fragments (in bp). For HindIII, allele-specific PCR can be performed using a primer specific for the HindIII polymorphism and a universal primer just outside the EagI/PacI polymorphism. Sequencing of the PCR product indicates linkage of HindIII with EagI and/or PacI. E, EagI; H, HindIII; N, NcoI; P, PacI; S, I-SceI. (C) The marker D14Mit95 is used to screen for distal LOH. (D) Polymorphisms used to examine LOH on chromosome 14. For each allele, the (TG)n repeat polymorphisms and SNPs are indicated with chromosome location (in Mb). Balb and B6 polymorphisms that differ are separated by a slash.

Fig. 2.

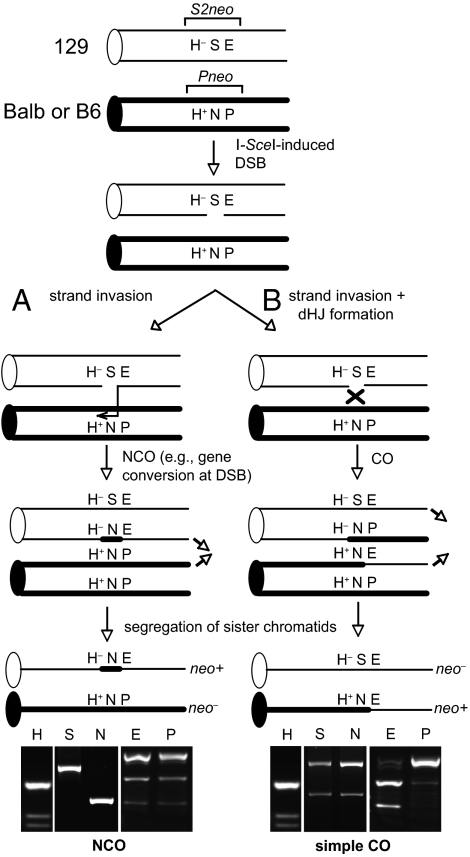

Interhomolog recombination resulting in an NCO or a simple CO. After DSB formation on a 129 chromatid (thin line), strand invasion into a B6 or Balb chromatid (thick line) can result in an NCO (A). In this particular case, gene conversion is limited to the site of the DSB. If strand invasion is followed by formation of a double Holliday junction (dHJ) (B), resolution can result in a CO product. Segregation of the nonexchange 129 chromatid with the indicated exchange chromatid results in a neo+ clone with LOH along the distal end of the chromosome. Representative analyses of markers are shown.

LOH of Distal Markers Is Infrequent Among Interhomolog Recombination Events in Wild-Type Cells.

Based on the S/P reporter design, neo+ colonies arising from a simple CO at S/G2 with segregation of recombinant chromatids (Fig. 2B) would be expected to have homozygozed the chromosome region distal to the DSB to that of the 129 chromosome (LOH129). A break-induced replication (BIR) mechanism as described in yeast has the potential to give rise to LOH129, although it is rare in wild-type yeast cells compared with COs (19) and would require replication through the centromere, which impedes BIR (20). We performed a large-scale screen of DSB-induced recombination events specifically to uncover events leading to LOH of distal markers. The I-SceI expression vector was transfected into S/P cells, which were then plated and selected to obtain neo+ recombinant colonies. In total, 898 neo+ recombinant colonies were then screened for LOH of the D14Mit95 marker, a distal TG-repeat polymorphism 36.8 megabase pairs (Mb) from the DSB (Fig. 1 C and D and Fig. S2A). From this analysis, 12 recombinant colonies exhibited LOH, having only the 129 allele at this polymorphism (1.3%; Table 1). In contrast, all 12 maintained heterozygosity for the centromeric D14Mit47 marker (Fig. 1D). These clones are best explained by crossing over, with chromatid segregation giving rise to a clone with LOH of distal markers (Fig. 2B and below). Centromeric heterozygosity also was confirmed by cytogenetics, because the amount of heterochromatin for chromosome 14 differs in the two strains (see, e.g., Fig. 3).

Table 1.

DSB-induced interhomolog recombination and CO-LOH

| S/P cell line | BLM protein | neo+ frequency (×10−5)* | No. neo+ clones | CO-LOH† (no. clones) |

| 129/Balb | + | 4.6 ± 1.5‡ | 898§ | 129: 1.3% (12) |

| 129/B6 (Blmtet/tet) | ||||

| – Doxycycline | + | 11.8 ± 1.6 | 314 | 129: 2.5% (8) |

| + Doxycycline | – | 4.6 ± 2.2¶ | 310 | 129: 12.9% (40) |

| + Doxycycline** | – | n.d. | 128 | 129: 17.2% (22) |

| B6: 16.4% (21) |

*Corrected for survival after electroporation; average ± SEM, n = 3.

†As inferred from a screen for LOH at the distal D14Mit95 marker and heterozygosity at proximal markers.129, CO-LOH129 ; B6, CO-LOHB6.

‡Previously determined (5).

§The 736 clones analyzed in this study plus 162 clones previously analyzed (5).

¶Corrected for survival after electroporation and clonogenic survival. For – doxycycline vs. + doxycycline, P = 0.03 with paired Student's t test.

**CO-LOH determined by analysis of random clone analysis from trypsinized neo+ colonies rather than by direct analysis of neo+ colonies.

Fig. 3.

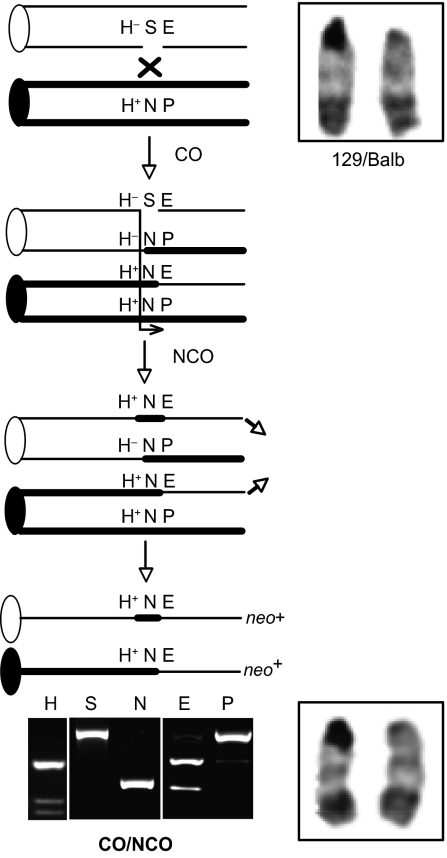

CO-LOH can be associated with an NCO on the other chromatid. CO-LOH129 that is associated with an NCO on the other 129 chromatid can be identified by conversion of the I-SceI site on both chromatids. Chromosome 14 in the 129/Balb parental cells and neo+ colonies is heteromorphic, with one chromosome showing minimal pericentric heterochromatin, indicating retention of heterozygosity at the centromere. No gross chromosomal rearrangements were observed in the recombinant chromosomes.

In a simple CO, the Balb/129 exchange chromatid containing the neo+ gene segregates with the nonexchange 129 chromatid containing an intact S2neo gene (Fig. 2B). PCR across the DSB site would give two products, one cleaved by NcoI and the other by I-SceI (Fig. 2B); these products were found in one such clone. In this clone, all markers distal to the DSB had undergone LOH, and all markers centromeric to the DSB maintained heterozygosity; i.e., the closest distal polymorphism (PacI/EagI, 530 bp from the DSB) had undergone LOH to the EagI site found on the 129 allele, whereas the closest centromeric polymorphism (HindIII+/−, 340 bp from the DSB), maintained heterozygosity (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. 2B).

The remaining 11 clones were more complex, in that the I-SceI site on the other 129 chromatid also was converted to an NcoI site, suggestive of a CO involving one 129 chromatid and an NCO on the other (CO/NCO; Fig. 3). From additional analysis of eight clones using allele-specific PCR to determine linkage of polymorphisms (Fig. 1B), these CO/NCO clones could be divided into several classes according to the extent of gene conversion on each chromatid beyond the DSB site (Fig. 4). In two clones, both chromatids converted only the DSB site (CO/NCO; Fig. 3). In two others, the NCO chromatid additionally converted the HindIII polymorphism (CO/NCO-H; Fig. S3), and one other clone converted the PacI polymorphism (CO/NCO-P; Fig. S3), as determined by allele-specific PCR (Fig. 1B). In three clones, the CO chromatid converted the HindIII polymorphism (CO-H/NCO; Fig. S4), with conversion (or the point of crossing over) extending at least 6 kb, and in one clone at least 5.6 Mb, beyond the HindIII site. A summary is provided in Fig. S5.

Fig. 4.

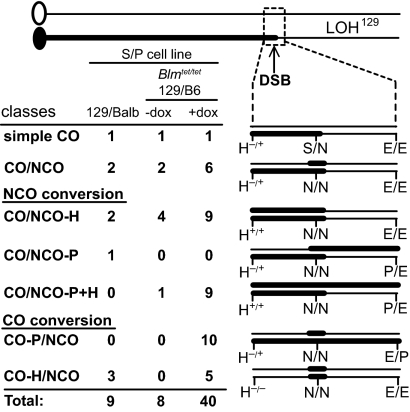

Classes of CO-LOH129 clones from wild-type and Blmtet/tet cells. CO-LOH129 clones are divided into classes, depending on whether the event was a simple CO or included an NCO on the other 129 chromatid (CO/NCO) and the extent of gene conversion associated with either the NCO (NCO conversion) or CO (CO conversion). The number of clones in each class is indicated.

LOH of Distal Markers Is Increased in BLM-Deficient Cells.

To examine the role of BLM in interhomolog recombination and CO-LOH, the S/P reporter was introduced into a mouse ES cell line in which BLM expression can be turned off by doxycycline (13). In these Blmtet/tet cells, derived from C57BL/6 × 129/Sv F1 (129/B6) embryos, the S2neo gene was targeted to the 129-derived chromosome 14, and the Pneo gene was targeted to the B6-derived chromosome 14 (Fig. S1). We found a 2.6-fold decrease in the overall rate of interhomolog recombination with loss of BLM (Table 1). There was no indication that the lower HR frequency is caused by reduced cleavage of the I-SceI site (Fig. S6), because the frequency of imprecise nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) was similar with or without BLM expression. Thus, loss of BLM does not result in a hyper-recombination phenotype for DSB-induced HR, consistent with previous results using a direct-repeat HR substrate (21).

To identify LOH, 314 neo+ recombinant colonies obtained in the absence of doxycycline (BLM-proficient) were examined; only eight exhibited LOH of the D14Mit95 marker, all to 129 (2.5% LOH129; Table 1 and Fig. S5). By contrast, of 310 neo+ recombinant colonies obtained in the presence of doxycycline (BLM-deficient), 40 exhibited LOH of this distal marker, all to 129 (12.9% LOH129). Thus, BLM deficiency leads to a five- to 10-fold increase in clones with LOH from interhomolog HR.

We further analyzed several additional polymorphisms along the length of the chromosome, including five centromeric to the DSB and three distal to the DSB (Fig. 1D and Table S1). SNPs were analyzed by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing (Fig. S2B). In all clones exhibiting LOH of the D14Mit95 marker, homozygosity to the 129 chromosome was observed for all distal markers, and heterozygosity was maintained for all centromeric markers, consistent with BLM suppression of CO-LOH during DSB-induced interhomolog recombination.

Two of these CO-LOH129 clones were consistent with a simple CO, maintaining the I-SceI site on the nonexchange chromatid (Fig. 4). The remaining clones converted the I-SceI site on the nonexchange chromatid, indicating an NCO event (Fig. 5A). As with the CO/NCO clones from the wild-type S/P cell line, clones could be placed in several classes, depending on the extent of gene conversion (or point of crossing over) on each chromatid. Among the large number of CO-LOH129 clones obtained with doxycycline treatment, a new class was detected in which gene conversion during crossing over extended to the PacI site; consequently, the NCO chromosome contained the neo+ gene (CO/P-NCO; Fig. 4 and Fig. S4). Thus, the frequent conversion of both chromatids permitted the detection of CO events that were nonproductive for restoring neo gene function.

Fig. 5.

Frequent association of two HR events during interhomolog recombination. (A) CO/NCO resulting in detectable CO-LOH129. Both neo+ chromatids segregate to the same daughter cell. (B) CO/NCO resulting in detectable CO-LOH129 and CO-LOHB6. The neo+ chromatids segregate to separate daughter cells forming a mixed neo+ colony. Subcloning will identify such events. (C) Two NCO events that segregate into separate daughter cells forming a mixed neo+ colony. If conversion is longer in one NCO than in the other, the two NCOs can be molecularly distinguished from one NCO event. (D) CO formation results in a mitotic bivalent, which could spatially and temporarily favor repair of a second DSB by HR. Dashed lines represent existing cohesion between sister chromatids; this cohesion holds the CO chromatids together, forming a mitotic bivalent, until cohesion loss.

Detection of the Reciprocal CO Product.

The identification of the new CO-P/NCO class suggested that neo+ genes potentially could arise on either CO chromatid (Fig. 5 A and B). Segregation of the reciprocal CO products away from each other then could result in a daughter cell containing a neo– gene with CO-LOH129 and the other daughter cell containing a neo+ gene with CO-LOHB6 (Fig. 5B and Fig. S4D). An associated NCO in the daughter cell with CO-LOH129 would mask CO-LOHB6, so that the resultant colony would therefore appear to be heterozygous at the D14Mit95 marker. Attempting to uncover these events, we performed random clone analysis of recombinants from BLM-deficient cells, such that a pool of neo+ colonies was trypsinized and replated before clone analysis. From a total of 128 random neo+ clones, 22 CO-LOH129 and 21 CO-LOHB6 clones were obtained (17.2% and 16.4%, respectively, or 33.6% total). Thus, the reciprocal CO-LOHB6 product was readily obtained.

To estimate how often both daughter cells contained a neo+ gene (as in Fig. 5B), 39 individual neo+ colonies from BLM-deficient cells were trypsinized, and subclones of these individual neo+ colonies were analyzed for LOH. Nine of the 39 colonies gave rise to subclones with LOH: six with only CO-LOH129, two with only CO-LOHB6, and one with both CO-LOH129 and CO-LOHB6. Thus, most COs give rise to LOH events in which only one daughter cell would be scored by neo+ selection. The structure of the one CO-LOH129/CO-LOHB6 colony allowed us to follow the outcome of all four chromatids of a mammalian mitotic bivalent (Fig. S7).

A Second HR Event Is Associated More Often with COs than with NCOs.

The frequent occurrence of CO-LOH129 and NCO events in the same neo+ clone (CO/NCO) in both wild-type and BLM-deficient cells could result from the frequent cleavage of both chromatids during I-SceI expression; alternatively, the two events could be linked mechanistically. To test these possibilities, we titrated the transfected I-SceI expression vector to levels that reduced interhomolog recombination 10-fold but allowed a significant number of neo+ colonies for molecular analysis. Reduced I-SceI expression had no effect on the fraction of CO/NCO clones (31 of 33 clones compared with 21 of 22 clones with standard I-SceI expression) despite the dramatically reduced overall level of recombination.

These results raised the possibility that the CO and NCO events are linked mechanistically, but they still could reflect frequent cleavage of both chromatids. To address this possibility, we next asked whether two NCO events also frequently co-occurred in the same colony. Unlike CO/NCO events in which the two neo+ chromatids segregate to the same daughter cell (Fig. 5A), neo+ NCO events on both 129 chromatids will segregate to different daughter cells (Fig. 5C). The neo+ colonies are informative for two NCO events if one recombinant 129 chromatid contains a HindIII+neo+ gene and the other recombinant 129 chromatid contains a HindIII−neo+ gene (Fig. S8). With allele-specific PCR, 15% of all neo+ colonies derived from reduced I-SceI expression were determined to arise from two NCO events. The remaining colonies arose either from one NCO or from two NCOs that were identical at the HindIII polymorphism (HindIII+ or HindIII−) on the 129 chromatid. Given that the HindIII site is converted in roughly half of NCOs [40/83 (48%) with doxycycline and 17/33 (51%) without doxycycline, P = 0.84; random clone analysis], colonies arising from two identical NCOs are expected to be similar in number to those arising from two different NCOs (15%). Thus, the fraction of neo+ colonies with two NCOs is estimated to be 30% (from 462 total colonies analyzed), significantly lower than the fraction of CO/NCO events (31/f 33 CO-LOH129 clones, 94%; P < 0.0001). These results support an association between crossing over and a second HR event.

Discussion

Although the cellular hallmark of BLM-deficient cells is a high level of sister-chromatid exchange, the likelihood of crossing over at a defined DNA lesion had not been examined previously in these cells. Here we demonstrate that BLM deficiency leads to a substantial increase in the efficiency of LOH of distal markers, presumably resulting from crossing over between homologs. The overall frequency of interhomolog recombination was not increased by BLM deficiency, indicating that BLM does not suppress recombination per se; rather, it promotes resolution of recombination intermediates into NCOs. The RecQ helicase in budding yeast, Sgs1, has been shown to have a similar role during interchromosomal recombination (15).

The preponderance of NCOs in mitotically dividing cells has led to strong support for the dominance of the synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) pathway for DSB repair (15). DSB repair through a double Holliday-junction intermediate therefore is considered to be a minor pathway, giving rise to infrequent COs. An alternative to the SDSA pathway for NCO formation is dissolution of double Holliday junctions (15). Biochemical studies have demonstrated that BLM in a complex that includes TOPOIIIα and RMI1 dissolves double Holliday junctions (14, 22, 23), and genetic studies provide evidence for a similar role for Sgs1 in yeast (24). In BLM-deficient cells, we observed that a substantial portion of clones had undergone LOH, suggesting that double Holliday-junction intermediates may form more frequently than expected during HR in mammalian cells but are dissolved by BLM.

In addition to dissolution of double Holliday junctions, BLM has other biochemical activities that can affect HR, although it is less clear how these activities would affect crossing over specifically. For example, BLM has been implicated in promoting end resection (25), similar to the Sgs1 ortholog in yeast (26), and in disrupting both D-loops and Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments (27, 28). BLM activity in end resection could account for the small overall reduction of HR in BLM-deficient cells (Table 1) (21), but reduced resection activity is not expected to promote crossing over specifically, because short resected ends are less likely to form the stable D-loop intermediates that give rise to COs (29, 30). The end resection activity of Sgs1 has been implicated in suppressing a specialized form of HR, namely, BIR (31, 32). Although we cannot rule out with certainty that BIR contributes to some of the LOH events, BIR giving rise to LOH129 would require synthesis through the centromere, which appears to impede BIR in yeast (Fig. S4E) (20). A role for BLM in the disruption of D-loops and/or Rad51 filaments is more plausible than end resection in suppressing LOH but would require BLM's having a more profound effect on disrupting stable D-loop intermediates destined for crossing over or long Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments that are more likely to be converted to those intermediates.

In wild-type mouse cells, we infer that COs comprise a few percent of recombination events. A previous study examining DSB-induced interhomolog recombination events in wild-type human lymphoblastoid cells reported that COs comprised a somewhat greater fraction of recombinants than we observed, although it is probable that all interhomolog NCOs could not be scored, given the requirement for coconversion of markers (8). An NCO bias also is observed for meiotic interhomolog recombination, but this bias is less pronounced since COs are estimated to comprise ∼10% of events (see ref. 30 and references therein).

In wild-type and BLM-deficient cells, we observed that the vast majority of CO clones contained an NCO on the other allele. COs in wild-type human cells similarly were found to be associated with NCOs (8). These results raise two questions: Why are COs frequently associated with a second DSB repair event, and why does this second event occur exclusively by HR? Given the overall low frequency of interhomolog recombination, the frequent association of crossing over with an HR event on the other chromatid could reflect frequent I-SceI cleavage of nearby sister chromatids in S/G2 followed by HR repair. Consistent with frequent cleavage of both sisters, our analysis also uncovered colonies that had undergone two NCOs. However, it is notable that colonies with two NCOs are estimated to comprise a significantly lower fraction of total colonies with NCOs (30%) than CO/NCOs comprise of total CO-LOH129 colonies (94%).

One explanation for CO/NCO events is that if two DSBs arise by I-SceI cleavage, a CO at one DSB is more likely than an NCO to promote an HR event at the second chromatid. Related to this notion, we never observed a CO associated with an NHEJ event. This absence is remarkable, because NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle (33) and is orders of magnitude more frequent than interhomolog HR (Fig. S6), suggesting that NHEJ either is precluded from accessing DNA ends on the other chromatid and/or that HR is specifically promoted. The structure of a mitotic bivalent may influence repair of the second DSB (Fig. 5D): CO-LOH events occur in S/G2 when sister chromatids are present, so a CO can lead to a bivalent with all four chromatids held together until cohesion is released, akin to a meiotic bivalent (34). In this configuration, a DSB at the other I-SceI site has three chromatids (i.e., the chromatid from the homolog and the two recombinant chromatids) as potential repair templates in close proximity. Although we cannot definitively identify the repair template for the associated NCOs, at least a portion of events (e.g., CO/NCO-P+H) is explained best by interhomolog HR, consistent with the homolog's being held in close proximity. Thus, as long as a mitotic bivalent structure formed by crossing over is maintained by sister chromatid cohesion, the proximity of chromatids could promote repair of a second DSB via HR. By contrast, interhomolog NCOs would maintain proximity only during the NCO event itself.

An alternative or additional explanation for a preponderance of COs associated with a second HR event is that, rather than arising from two DSBs in S/G2, COs arise from a single DSB that is converted to two DSBs upon DNA replication. This single DSB could form in G1, which in mouse ES cells may be especially likely to persist into S phase because of the lack of a robust G1/S checkpoint (35). A single DSB in S phase in an unreplicated portion of the chromosome is also possible. In either case, replication would give rise to two broken sister chromatids, so that intersister HR would be precluded, increasing the likelihood of interhomolog HR. Strong evidence has been provided in yeast that mitotic COs arise from a DSB on an unreplicated chromosome (36–38). Additionally, the involvement of three or four chromatids in a joint molecule could by itself promote crossing over, because joint molecules are increased in the absence of Sgs1 during meiosis (39). Alternatively, DNA ends created by replication may be more prone to crossing over; for example, ends formed by lagging strand synthesis have 3′ overhangs which promote HR. Further, merging these two possibilities, lagging strand ends from two chromatids could promote multichromatid interactions to promote crossing over.

Materials and Methods

For detailed materials and methods, please see SI Materials and Methods.

Wild-type S/P cells (5) and Blmtet/tet ES cells (13) containing the S2neo gene (21) were described previously. To suppress BLM expression in Blmtet/tet cells, doxycycline was added to the medium at a final concentration of 1 μg/mL 48 h before transfection and was removed 24 h after transfection. For HR assays, 1.3 × 107 ES cells in 0.65 mL PBS or OPTI-MEM were electroporated (250 V, 950 μF) with 25 or 5 μg of either the I-SceI expression plasmid (pCBASce) or the empty vector (pCAGGS) and divided into five 10-cm plates. At 24 h, one plate was trypsinized and counted to determine the number of cells that survived electroporation. G418 (Gibco) was added to the rest of the plates at 200 μg/mL for 9–12 d. Interhomolog recombination frequencies were determined by dividing the number of G418-resistant colonies by the number of cells that survived electroporation. For Blmtet/tet ES cells, we also accounted for a 1.4-fold decrease in colony formation when BLM was suppressed. For molecular analysis, neo+ colonies were expanded in 96-well plates and then were replica plated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret Leversha at the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center Molecular Cytogenetics Core Facility for the cytogenetic analysis and the M.J. laboratory for helpful comments regarding experimental design and analysis. This work was supported by National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship F32GM084637 (to J.R.L.) and by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM54668 and National Science Foundation Grant 0346354 (to M.J.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1104421108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cavenee WK, et al. Expression of recessive alleles by chromosomal mechanisms in retinoblastoma. Nature. 1983;305:779–784. doi: 10.1038/305779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiagalingam S, et al. Mechanisms underlying losses of heterozygosity in human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2698–2702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagstrom SA, Dryja TP. Mitotic recombination map of 13cen-13q14 derived from an investigation of loss of heterozygosity in retinoblastomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2952–2957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasin M. In: In DNA Alterations and Cancer. Ehrlich M, editor. Natick, MA: Eaton Publishing; 2000. pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stark JM, Jasin M. Extensive loss of heterozygosity is suppressed during homologous repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:733–743. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.733-743.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole F, Keeney S, Jasin M. Evolutionary conservation of meiotic DSB proteins: More than just Spo11. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1201–1207. doi: 10.1101/gad.1944710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moynahan ME, Jasin M. Mitotic homologous recombination maintains genomic stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:196–207. doi: 10.1038/nrm2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuwirth EAH, Honma M, Grosovsky AJ. Interchromosomal crossover in human cells is associated with long gene conversion tracts. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5261–5274. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01852-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis NA, et al. The Bloom's syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655–666. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.German J, Schonberg S, Louie E, Chaganti RS. Bloom's syndrome. IV. Sister-chromatid exchanges in lymphocytes. Am J Hum Genet. 1977;29:248–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo G, et al. Cancer predisposition caused by elevated mitotic recombination in Bloom mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26:424–429. doi: 10.1038/82548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langlois RG, Bigbee WL, Jensen RH, German J. Evidence for increased in vivo mutation and somatic recombination in Bloom's syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:670–674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yusa K, et al. Genome-wide phenotype analysis in ES cells by regulated disruption of Bloom's syndrome gene. Nature. 2004;429:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu L, Hickson ID. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature. 2003;426:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welz-Voegele C, Jinks-Robertson S. Sequence divergence impedes crossover more than noncrossover events during mitotic gap repair in yeast. Genetics. 2008;179:1251–1262. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McVey M, Andersen SL, Broze Y, Sekelsky J. Multiple functions of Drosophila BLM helicase in maintenance of genome stability. Genetics. 2007;176:1979–1992. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.070052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Smith K, Waldman BC, Waldman AS. Depletion of the Bloom syndrome helicase stimulates homology-dependent repair at double-strand breaks in human chromosomes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho CK, Mazón G, Lam AF, Symington LS. Mus81 and Yen1 promote reciprocal exchange during mitotic recombination to maintain genome integrity in budding yeast. Mol Cell. 2010;40:988–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrow DM, Connelly C, Hieter P. “Break copy” duplication: A model for chromosome fragment formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:371–382. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaRocque JR, Jasin M. Mechanisms of recombination between diverged sequences in wild-type and BLM-deficient mouse and human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1887–1897. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01553-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, et al. BLAP75/RMI1 promotes the BLM-dependent dissolution of homologous recombination intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4068–4073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508295103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bussen W, Raynard S, Busygina V, Singh AK, Sung P. Holliday junction processing activity of the BLM-Topo IIIalpha-BLAP75 complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31484–31492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bzymek M, Thayer NH, Oh SD, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Double Holliday junctions are intermediates of DNA break repair. Nature. 2010;464:937–941. doi: 10.1038/nature08868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimonkar AV, Ozsoy AZ, Genschel J, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC. Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16906–16911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809380105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Nucleases and helicases take center stage in homologous recombination. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bachrati CZ, Borts RH, Hickson ID. Mobile D-loops are a preferred substrate for the Bloom's syndrome helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2269–2279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bugreev DV, Yu X, Egelman EH, Mazin AV. Novel pro- and anti-recombination activities of the Bloom's syndrome helicase. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3085–3094. doi: 10.1101/gad.1609007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter N, Kleckner N. The single-end invasion: An asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-Holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2001;106:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole F, Keeney S, Jasin M. Comprehensive, fine-scale dissection of homologous recombination outcomes at a hot spot in mouse meiosis. Mol Cell. 2010;39:700–710. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marrero VA, Symington LS. Extensive DNA end processing by exo1 and sgs1 inhibits break-induced replication. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lydeard JR, Lipkin-Moore Z, Jain S, Eapen VV, Haber JE. Sgs1 and exo1 redundantly inhibit break-induced replication and de novo telomere addition at broken chromosome ends. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothkamm K, Krüger I, Thompson LH, Löbrich M. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5706–5715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter N. In: In Topics in Current Genetics, Molecular Genetics of Recombination. Aguilera A, Rothstein R, editors. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. pp. 381–442. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aladjem MI, et al. ES cells do not activate p53-dependent stress responses and undergo p53-independent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Curr Biol. 1998;8:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roman H, Fabre F. Gene conversion and associated reciprocal recombination are separable events in vegetative cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee PS, et al. A fine-structure map of spontaneous mitotic crossovers in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee PS, Petes TD. Mitotic gene conversion events induced in G1-synchronized yeast cells by gamma rays are similar to spontaneous conversion events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7383–7388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh SD, et al. BLM ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell. 2007;130:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.