Abstract

The heterochromatin barrier must be overcome to generate induced pluripotent stem cells and cell fusion-mediated reprogrammed hybrids. Here, we show that the absence of T-cell factor 3 (Tcf3), a repressor of β-catenin target genes, strikingly and rapidly enhances the efficiency of neural precursor cell (NPC) reprogramming. Remarkably, Tcf3−/− ES cells showed a genome-wide increase in AcH3 and decrease in H3K9me3 and can reprogram NPCs after fusion greatly. In addition, during reprogramming of NPCs into induced pluripotent stem cells, the silencing of Tcf3 increased AcH3 and decreased the number of H3K9me3-positive heterochromatin foci early and long before reactivation of the endogenous stem cell genes. In conclusion, our data suggest that Tcf3 functions as a repressor of the reprogramming potential of somatic cells.

Keywords: Wnt pathway, induced pluripotent stem cell generation

Overexpression of defined factors and modulation of signaling pathways can induce somatic cell reprogramming of differentiated cells. The process that leads to the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) usually takes several weeks to complete, and it is normally very inefficient (1). Somatic cell reprogramming can also be achieved via their fusion with stem cells (2). We have shown that Wnt3a-mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway enhances cell fusion-mediated reprogramming of a variety of somatic cells (3). In addition, the number of iPSC clones was increased when mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) infected with retroviruses expressing Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 were cultured in Wnt3a-conditioned medium (4). Likewise, a large number of iPSCs were obtained when human primary keratinocytes were transduced with Oct4 plus Klf4 (OK) and cultured in the presence of CHIR99021 [a glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) inhibitor that activates the Wnt pathway] (5).

One effect of activation of the Wnt canonical pathway is the inactivation of the destruction complex APC/GSK3/Axin. As a consequence, β-catenin is not phosphorylated by GSK3; instead, it translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to target promoters through its interactions with the Tcf proteins. Tcf1 (Tcf7), Lef-1, Tcf3 (Tcf7l1), and Tcf4 (Tcf7l2) form a family of transcription factors that modulate transcription of genes by recruiting chromatin remodeling and histone-modifying complexes to their target genes (6, 7). Tcf3 is the most frequently expressed of the Tcf isoforms in ES cells (8) (see Fig. S3A), and it coregulates specific classes of target genes by associating with their promoter regions, along with Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 (9). Tcf3 has a dual function: It can repress β-catenin target genes by recruiting corepressor factors, and it can activate the same or different classes of genes by interacting with β-catenin and by recruiting different sets of cofactors (6). Interestingly, in gastrulating Xenopus embryos and mammalian cells, on Wnt signaling activation, Tcf3 was shown to be phosphorylated by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) and to dissociate from target promoters. This suggested an alternative model for Tcf3 activity that recognizes Tcf3 to be mainly a repressor, which, once phosphorylated, can leave Wnt-target genes, which, in turn, become derepressed and transcriptionally active (10).

We have shown that constitutive activation of the Wnt pathway in GSK3−/− ES cells leads to a block in the reprogramming activity of somatic cells after fusion. This was attributable to very high levels of active β-catenin in the nucleus of GSK3−/− ES cells; indeed, ES cell clones expressing high levels of β-catenin also cannot reprogram somatic cells after fusion. In contrast, ES cell clones expressing low levels of β-catenin showed high reprogramming capacities (3).

We thus investigated whether deletion of Tcf3, and therefore derepression of β-catenin target genes, can enhance the reprogramming activity. Here, we show that Tcf3 represses Oct4 plus Klf4 (OK)-induced reprogramming of neural precursor cells (NPCs). Deletion of Tcf3 enhances both cell fusion-mediated and direct reprogramming. Furthermore, we show that the increased reprogramming efficiency is largely attributable to genome-wide epigenome modifications that occur before the endogenous stem cell genes are reactivated in the iPSC clones.

Results

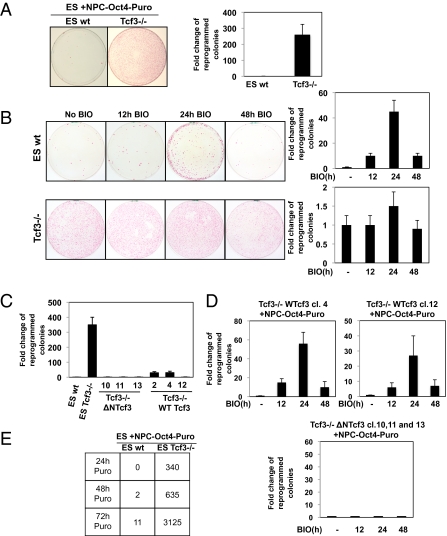

The deletion of Tcf3 derepresses the transcription of β-catenin–dependent genes (8, 9, 11). To determine whether the deletion of Tcf3 in ES cells can enhance cell fusion-mediated reprogramming, we cocultured somatic NPCs carrying the Oct4-Puro-GFP transgene (puromycin resistance and GFP, under the control of the Oct4 promoter) with WT ES cells or Tcf3−/− ES cells (Fig. S1A). The cells fused spontaneously without addition of polyethylene glycol (12), and deletion of Tcf3 did not increase the efficiency of fusion (Fig. S1B). WT and Tcf3−/− cells were not resistant to puromycin selection (Fig. S1C), whereas reprogrammed clones were selected by Oct4 reactivation by adding puromycin to the hybrids. The puromycin-resistant clones were tetraploids (Fig. S2A), were GFP-positive (Fig. S2B), expressed pluripotent markers, and silenced neural markers (Fig. S2 C and D). They were stained for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) expression, a stem cell marker (13), and counted. The reprogramming of NPCs was 300-fold higher after fusion with Tcf3−/− ES cells with respect to fusion with WT ES cells (Fig. 1A). This effect was not attributable to the activities of the other Tcf family members (i.e., Tcf1, Lef-1, Tcf4) because they were expressed at the same levels in WT and Tcf3−/− ES cells (Fig. S3B). Also, it was not attributable to an increase of stabilized β-catenin in these cells (Fig. S4B, compare with NO BIO samples). On average, 1,200 reprogrammed clones were obtained after coculturing 1 × 106 cells of each of the two cell types.

Fig. 1.

Deletion of Tcf3 in ES cells increases reprogramming of NPCs after cell fusion. (A) Bright fields of hybrid colonies formed between WT (wt) ES cells plus NPCs and Tcf3−/− ES cells plus NPCs stained for ALP expression are shown. Quantification of reprogramming efficiency (fold increases in colony numbers) is shown in the graph. WT ES cells and Tcf3−/− ES cells have the same genetic background. (B) ES cells (WT and Tcf3−/−) were pretreated with 1 μM BIO for the indicated times and then cocultured with NPCs-Oct4-puro. (Right) Representative growth plates with quantification of reprogramming efficiency (fold increases in colony numbers) of the cocultured cells (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (C) Quantification of reprogramming efficiency (fold increases in colony numbers) of different Tcf3−/− ES cell clones expressing a truncated Tcf3 (Tcf3−/−ΔΝTcf3) form or WT Tcf3 (Tcf3−/−WTcf3) cocultured with NPCs-Oct4-puro (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (D) Different Tcf3−/−ΔNTcf3 and Tcf3−/−WTcf3 ES cell clones were pretreated with BIO for the indicated times and then cocultured with NPCs-Oct4-puro. Reprogramming efficiency (fold increases in colony numbers) of the cocultured cells is shown (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (E) ES cells (WT and Tcf3−/−) and NPCs-Oct4-puro were cocultured, and puromycin selection was applied at the indicated times. The total number of reprogrammed colonies in three experiments is indicated.

Interestingly, the reprogramming efficiency did not increase further when NPCs were cocultured with Tcf3−/− ES cells that had been pretreated with the Gsk3 inhibitor BIO (14) for different times at a concentration of 1 μM (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, increasing the BIO concentration resulted in increased β-catenin nuclear accumulation and a consequent increase in TCF/LEF-TopFlash activity, although there was a decrease in the reprogramming efficiency after fusion (Fig. S4 B–D). In contrast, and as we have previously shown, WT ES cells enhanced the reprogramming of NPCs, compared with the controls, when they were pretreated for 24 h with BIO before fusion, although they did not enhance reprogramming when they were pretreated for 12 or 48 h (Fig. 1B). We have shown previously that this time-dependent reprogramming is attributable to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin at the 24-h time point up to a specific threshold level (3) (Fig. S4A). Furthermore, high β-catenin accumulation in β-catenin–expressing ES cell clones and in the GSK3−/− ES cells impaired reprogramming activity after fusion (3, 12), and this was not attributable to a transcriptional increase in Tcf3 in these cells (Fig. S5A) but, rather, to the activation of the Axin2-dependent negative feedback loop (3).

Next, to confirm the essential role of Tcf3 in the reprogramming process, we generated Tcf3−/− ES clones that express a WT Tcf3 or a truncated Tcf3 form that cannot interact with β-catenin (7) (called Tcf3−/−WTcf3 and Tcf3−/−ΔΝTcf3, respectively) (Fig. S5B). Both Tcf3−/−WTcf3 and Tcf3−/−ΔΝTcf3 clones did not reprogram NPCs after fusion (Fig. 1C). This effect was reversed by pretreatment of the Tcf3−/−WTcf3 clones with BIO for 24 h but not when Tcf3−/−ΔΝTcf3 clones were pretreated with BIO before fusion (Fig. 1D).

All in all, these data clearly show that deletion of the Tcf3 repressor can allow ES cells to reprogram somatic cells with high efficiency and, furthermore, that this process is not attributable to an increased accumulation of nuclear β-catenin; rather, high levels of β-catenin block reprogramming activity even in absence of the Tcf3 repressor.

Next, we examined whether the reprogramming process was more rapid in the absence of Tcf3. We usually started the puromycin selection of reprogrammed clones 72 h after the coculturing of the cells. This allows sufficient time for the hybrids to be reprogrammed and to survive the puromycin selection after reactivation of the Oct4 promoter (15, 16). When we applied puromycin selection 24 or 48 h after the coculturing of WT ES cells and NPCs, we could not select any viable clones because the puromycin killed all the cells before reactivation of the Oct4 promoter. Surprisingly, we were able to select a very large number of clones (340 GFP+ and puromycin-resistant colonies) by adding the puromycin only 24 h after the coculturing of Tcf3−/− ES cells and NPCs. The number of colonies increased even further when puromycin was applied 48 and 72 h after the coculturing (with 635 and 3,125 clones selected, respectively; Fig. 1E). These data show that as well as being more efficient, the reprogramming of somatic cells is more rapid when Tcf3 is deleted, and this might be attributable to constitutive derepression of specific Tcf3-targeted genes that can efficiently activate reprogramming of somatic cells in trans after fusion.

Because Tcf3 can be released from target promoters after its phosphorylation (10, 17), we investigated whether β-catenin can activate target genes when it is in a complex with a different Tcf protein, such as Tcf1, which is also highly expressed in ES cells (Fig. S3A). Interestingly, the silencing of Tcf1 in Tcf3−/− ES cells (Fig. S6 A and B) completely abrogated their reprogramming activity after fusion (Fig. S6C). These results lead us to conclude that enhancement of reprogramming after derepression of Tcf3 target genes might be coupled to β-catenin/Tcf1-dependent activation of target promoters.

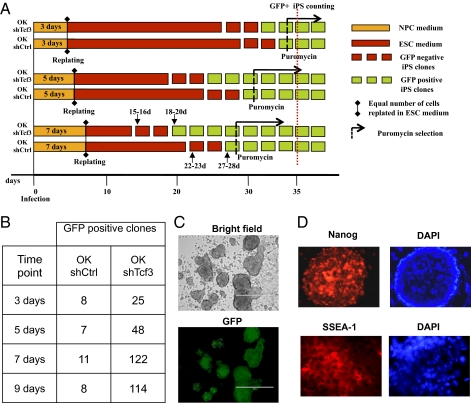

Next, we investigated whether silencing of Tcf3 increases the efficiency of iPSC generation. NPCs transduced with OK can generate iPSCs, although with a very low efficiency (18–20). Here, NPCs were infected with retroviruses carrying OK as well as with a retrovirus carrying the shRNA for Tcf3 or a control shRNA (OKshTcf3 and OKshCtrl). The cells were efficiently infected (Fig. S7A), and OK was efficiently expressed, whereas Tcf3 was efficiently silenced (Fig. S7 B and C). Cells were cultured for 3, 5, and 7 d in NPC medium (the 3-, 5- and 7-d time points), and the infected NPCs were then counted, replated in equal numbers in ES cell medium, and cultured for several weeks. In the plates in which NPCs were infected with OKshTcf3, ALP+ clones emerged in high numbers and very early: only 15 d after the infections, at the 7-d time point (Fig. 2A and Fig. S8A). Then, 18 d postinfection, the clones started to express GFP stably (7-d time point; a total of 122 GFP+ clones in 4 different experiments; mean: 31 ± 13 clones, n = 4) (Fig. 2 A and B). In the controls (NPCs-OKshCtrl) at the 7-d time point, the clones emerged later, at 22 d postinfection, and they started to express GFP 28 d postinfection. In addition, the number of clones was much lower (7-d time point; 11 GFP+ clones in 4 experiments; mean: 3 ± 3 clones, n = 4). The silencing of Tcf3 also increased the efficiency of reprogramming at the 3- and 5-d time points compared with the respective control time points because of an increased number of ALP+ and GFP+ clones and reduced timing of reprogramming (Fig. 2A and B and Fig. S8A). Both OKshTcf3-iPSCs and OKshCtrl-iPSCs showed an ES cell morphology; expressed Oct4-driven GFP; and also showed reactivation of endogenous Nanog, SSEA-1, Gdf3, and Fgf4, as well as silencing of the NPC markers Olig2 and Blbp (Fig. 2 C and D and Fig. S8B). Interestingly, the overexpression of Oct4 transgene was progressively silenced at the 3- and 7-d time points (Fig. S8C). In contrast, some puromycin-selected iPSC colonies showed efficient reactivation of endogenous Oct4 and Nanog, which was comparable to expression in ES cells, and they showed silencing of the transgenes (Fig. S8 D and E). Finally, the clones were pluripotent because they could differentiate in tissues of the three germ layers when injected s.c. into nude mice (epidermis, neural tissue, cartilage, muscle, and gut-like epithelium) (Fig. S8F). All in all, these data show that NPC-derived iPSCs can be generated in large numbers and in a timely manner by silencing Tcf3.

Fig. 2.

Generation of iPSCs is increased by Tcf3 silencing. (A) Experimental scheme indicating iPSC generation. NPCs-Oct4-puro were infected with OKshCtrl or OKshTcf3. Cells were maintained in NPC medium for 3, 5, or 7 d. Cells were then trypsinized and counted, and 70,000 cells were replated in ES cell medium. GFP+ and GFP− iPSCs appeared at the indicated times. Puromycin selection was applied at the indicated times. (B) Number of GFP+ iPS colonies obtained after infection with OKshCtrl or with OKshTcf3 in a total of four experiments. The colonies were counted at day 35 after infection. Representative images of GFP expression (C) and immunofluorescence for Nanog nuclear staining and SSEA-1 surface localization (D) in iPSCs.

We then investigated the molecular mechanisms by which Tcf3 deletion increased the efficiency of both fusion-mediated and direct reprogramming. We analyzed the levels of expression of the Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 genes in Tcf3−/− ES cells. These genes were previously shown to be dependent on Tcf3 for their transcription (9, 21). In accordance with previous work (11), we did not see an increase in Oct4 and Sox2 here; however, there was a small increase in Nanog expression in Tcf3−/− ES cells with respect to the WT cells (about a twofold increase) (Fig. 3A). To determine whether Tcf3−/− ESCs were more powerful in their reprogramming of somatic cells because of the increased Nanog expression, we increased the Nanog levels in WT ES cells to a level comparable to that measured in Tcf3−/− ESCs. In addition, we increased the Nanog levels in Tcf3−/− ES cells even further (Fig. S9A). Fusion-mediated reprogramming of NPCs with Tcf3−/− ES cells both without and with Nanog overexpression enhanced reprogramming of the somatic cells 300-fold over the control (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the twofold increase in Nanog in WT ES cells provided only a threefold enhancement of reprogramming after fusion compared with the control (Fig. 3B). These data ruled out a role for Nanog in increased reprogramming in the absence of Tcf3.

Fig. 3.

Deletion of Tcf3 leads to genome-wide epigenome modifications in ES cells. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog expression in WT (wt) and Tcf3−/− ES cells. (B) Quantification of reprogramming efficiency (fold increases in colony numbers) of ES cells (WT ES cells, Tcf3−/− ES cells, Nanog overexpressing Tcf3−/− ES cells, Nanog overexpressing WT ES cells) cocultured with NPCs-Oct4-puro (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (C) Western blotting quantification of histone modifications in untreated or BIO-treated WT ES cells and Tcf3−/− ES cells. All values are normalized relative to total H3 (t test: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; mean ± SEM, n = 3). (D) Representative Western blot analysis of histone modifications of protein extracts from WT and Tcf3−/− ES cells. (E) Quantitative ChIP assay for Oct4 target genes in WT and Tcf3−/− ES cells. Lefty2, Hoxb1, Tbx3, Nanog, Trp53b1, and Dppa3 are all Tcf3 and Oct4 target genes. Diablo and IGX1A are control nontarget genes. The fold enrichment for each promoter region vs. IgG control immunoprecipitation is shown, after normalization for input DNA (t test: *P < 0.05; mean ± SEM, n = 3).

Tcf3 recruits some repressive cofactors, such as Groucho, TLE-1, and histone deacetylase, to their target genes (22); as a result, it induces heterochromatin formation and global repression of transcription. We then asked whether activation of Wnt signaling can modify the epigenome profile of ES cells. WT ES cells were treated for 12, 24, and 48 h with BIO, followed by a genome-wide analysis of their epigenome. Only the 24-h–treated ES cells that were also able to reprogram somatic cells after fusion (Fig. 1B) showed a marked increase in acetylated H3, a marked decrease in H3K9me3, and a tendency to increase in H3K4me3, compared with untreated ES cells and ES cells that were BIO-treated for 12 and 48 h. There was no variation in H3K27me3 (Fig. 3C and Fig. S9B). The global modifications of these histone lysines indicated that the state of the chromatin was largely open and the presence of a substantial fraction of transcriptionally active euchromatin. Furthermore, and importantly, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway for a specific time (24 h) can induce massive histone modifications in ES cells. We then analyzed the Tcf3−/− ES cells and found that these cells also showed a similar genome-wide epigenome profile (Fig. 3 C and D). Thus, we analyzed some Tcf3 target and nontarget genes by ChIP in WT and Tcf3−/− ESCs. We found an increase of AcH3 and a decrease of H3K9Me3 in a subset of Tcf3 target genes but also in genes that were non-Tcf3 targets, which confirmed that chromatin in Tcf3−/− ESCs is genome-wide open and transcriptionally active (Fig. S9C).

Remarkably, the open state of the chromatin in Tcf3−/− ES cells also enhanced the binding of Oct4 to specific promoters of target genes, such as Lefty2, Hoxb1, Tbx3, Nanog, Trp53b1, and Dppa3, as measured by ChIP (Fig. 3E). These promoters were chosen because they have already been shown to be common targets of Tcf3 and Oct4 (9, 21). All these data demonstrate that in ES cells, deletion of Tcf3 or activation of the Wnt pathway for a specific time leads to the establishment of an open chromatin state and a general chromatin derepression that enhances the reprogramming efficiency.

Finally, to demonstrate further that the silencing of Tcf3 causes a modification of the epigenome that might be essential in the augmentation of the reprogramming process, we analyzed histone modifications during iPSC generation. NPCs were infected with OKshTcf3 or OKshCtrl. Then, 3, 5, and 7 d postinfection, they were replated in ES cell medium, cultured for a further 24 h, and analyzed for modifications of AcH3 and H3K9me3 by immunofluorescence and Western blotting (Fig. 4A). Only the cells in which Tcf3 was silenced showed a high level of AcH3 at the 5-d and 7-d time points (Fig. 4B), along with a decreased number of H3K9me3 heterochromatin foci at all time points, compared with cells infected with OKshCtrl (Fig. 4C). This was also confirmed by Western blotting using 5-d and 7-d total extracts (Fig. 4D and Fig. S9D). The numbers of heterochromatic foci in OKshCtrl- and OKshTcf3-infected NPCs were counted, and the curves from the experimental data were fitted. At all three time points, we observed a reduction in the number of heterochromatin foci in the OKshTcf3-infected NPCs with respect to the controls (OKshCtrl-infected NPCs) (Fig. 4C). This clearly shows that Tcf3 maintains the heterochromatin state and that its deletion leads to the opening of the chromatin. Interestingly, although there were epigenome modifications, these OKshCtrl- and OKshTcf3-infected NPCs did not show reactivation of stem cell genes, such as Oct4, Rex1, Fbx15, and Eras, up to 8 d postinfection. Only Nanog was partially reactivated in these infected NPCs (Fig. S9E). Reactivation of Oct4 and Nanog was seen only in puromycin-selected iPSC clones (Fig. S8 D and E). Finally, because previous studies have shown that reprogramming can result in large changes in nuclear volume (23), we estimated the nuclear areas of these infected NPCs. At the 7-d time point, OKshTcf3-infected NPCs and OKshCtrl-infected NPCs were cultured for 24, 48, and 72 h in ES cell medium and the areas of their nuclei were measured. The nuclei infected with OKshTcf3 showed a significantly greater calculated volume increase compared with the OKshCtrl-infected nuclei (Fig. 4E). These data indicate that silencing of Tcf3 induces epigenome modifications, formation of euchromatin, and nuclear volume increases in cells undergoing reprogramming. These events occurred very early and before reexpression of the endogenous stem cell genes.

Fig. 4.

NPC epigenome modifications induced by shTcf3. (A) Experimental scheme: NPCs-Oct4-puro were infected with OKshTcf3 or OKshCtrl. After 3, 5, and 7 d in NPC medium, the cells were trypsinized and replated in ES cell medium for an additional 24 h. AcH3 and H3K9me3 staining was then performed. (B) Representative images and quantification (Lower) of total H3 acetylation levels in NPCs infected with OKshCtrl or OKshTcf3. Intensity of AcH3 was evaluated using ImageJ software (mean ± SEM, n = 3; 100 cells in total were analyzed for each sample). (C) Representative images and quantification (Lower) of H3K9me3 heterochromatin foci. H3K9me3 staining was analyzed by immunofluorescence. The number of immunopositive H3K9me3 foci in the nuclei was counted (total of 70 nuclei were analyzed for each sample). Smoothing splines were fitted to the experimental data using the curve-fitting toolbox implemented in MATLAB R2009a (Mathworks). (D) Representative Western blot analysis of histone modifications of protein extracts from NPCs-Oct4-puro infected with OKshTcf3 or OKshCtrl. (E) Nucleus areas of OKshCtrl- and of OKshTcf3-infected NPCs. The cells were infected with OKshCtrl or OKshTcf3 and maintained in NPC medium for 7 d. Nucleus area was analyzed 24, 48, and 72 h after the shift to ES cell medium (mean ± SEM, n = 3; 100 cells were analyzed for each treatment time point and experiment; two-sample Wilcoxon test was used to calculate the P value).

Discussion

We have shown here that cell reprogramming can be induced with high efficiency by deletion of the repressor Tcf3. This Tcf3 ablation led to a massive genome-wide modification of the epigenome: an increase in AcH3, a slight increase in H3K4me3, and a decrease in H3K9me3. These modifications established an active transcriptional state of the chromatin that favored the enhancement of reprogramming (Fig. S9F). Indeed, the open state of the chromatin was also confirmed by the efficient binding of the endogenous Oct4 to target promoters in the Tcf3−/− ES cells. Interestingly, we did not observe changes in H3K27me3, which was also recently shown to be an essential marker for efficient reprogramming of human B cells (23, 24).

WT ES cells can reprogram somatic cells after fusion (13); however, this process is particularly inefficient. Here, we have shown that derepression of β-catenin target genes in Tcf3−/− ES cells can switch on a cascade of events that finally promotes the efficient reprogramming of somatic cells after their fusion. We previously showed that only a specific level of β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus of ES cells can enhance fusion-mediated reprogramming (3). To control gene expression, β-catenin must associate with the Tcf factors (6), and these, in turn, switch the recruitment of the corepressors to that of the coactivators of the target genes (22). Here, we show that deletion of Tcf3 strongly increases the efficiency of reprogramming, most likely through the constitutive release of the corepressors from the target genes that encode for reprogrammers (reprogramming factor-encoding genes). Interestingly, this appears not to be independent of β-catenin; rather, it appears to be coupled with the activity of the Wnt signaling pathway. In the absence of Tcf3, β-catenin appears to activate reprogramming in a complex with a Tcf activator, such as Tcf1. On the other hand, we cannot exclude a possible Tcf-independent β-catenin stabilization on target promoters (25).

Reprogrammed clones can be isolated not only in extremely large numbers but, importantly, by applying puromycin selection very early (i.e., 24 h after fusion). This indicates that the expression of the reprogrammers is already active in the Tcf3−/− ES cells and that these factors can act immediately after fusion with NPCs in trans. Reprogramming of human B-cell nuclei or human fibroblasts was also very rapid in the case of heterokaryon formation with mouse ES cells (23, 24). Importantly, our data show that silencing of Tcf3 is also valuable for the efficient derivation of iPSCs, which can be generated in large numbers and also in a short time (Fig. S9F).

Our observations indicate that deletion of Tcf3 strongly enhances reprogramming by modifying the epigenome and that this, in turn, leads to the expression of essential reprogrammers that can be reactivated by both stem and somatic cells. It is also worth noting that the largest number of iPSCs was selected when the cells were cultured in NPC medium for 7 d after being infected (i.e., under culture conditions that induce ES cell differentiation). We prolonged this time to 9 d, but we did not see any further improvement in the reprogramming efficiency (Fig. 2B). Because histone modifications, such as an increase in AcH3 and a decrease in H3K9me3 foci, had already started 5 d postinfection, 7 d appeared to be the right time for the reprogrammers to be expressed by the NPC genome. Indeed, we also saw increases in the nucleus volume, which might well be associated with high transcriptional activity. Thus, after these 7 d in NPC medium, when the cells were cultured for some additional days in ES cell medium, they were ready to complete their reprogramming and could be selected in large numbers.

In the OKshTcf3-infected NPCs, the transgenes were silenced with high efficiency and the endogenous stem cell genes were reactivated later on, a long time after their epigenome was modified (Fig. S9F). This indicates that the epigenome modifications, such as the increase in AcH3 and decrease in H3K9me3 heterochromatin foci, are epistatic to the stem cell gene reactivation and transgene silencing. Interestingly, the BAF complex components that modify the epigenome of MEFs facilitated Oct4 transgene binding to the target promoters during reprogramming very soon after infection (26), whereas we did not see reactivation of the endogenous Oct4, Rex1, Fbx15, or Eras for up to 8 d postinfection.

Tcf3−/− ES cells have been shown to differentiate poorly in vitro and in vivo, although they form embryoid bodies and teratomas (8); this is in apparent contrast to our present observation that deletion of Tcf3 induces extraordinary reprogramming. Evidently, this means that pluripotency can be dissociated from reprogramming potential and that different sets of genes control these two developmental fates. It will be very interesting in the future to dissect out these divergent pathways and genes that can push cells to embark on these two different states.

Materials and Methods

Cells.

NPCs-Oct4-puro were isolated from HP165 mice, and they carry the regulatory sequences of the mouse Oct4 gene driving GFP and puromycin-resistance genes. The NPCs-Oct4-puro were a gift from A. Smith (Wellcome Trust Centre for Stem Cell Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and were cultured as previously described (27). WT and Tcf3−/− ES cells have the same genetic background and were produced as previously described (28). ES cells were cultured on gelatin in KO DMEM supplemented with 20% FBS (HyClone), 1× nonessential amino acids, 1× GlutaMax (Invitrogen), 1× penicillin/streptomycin, 1× 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1,000 U/mL LIF ESGRO (Chemicon). BIO was added to a concentration of 1 μM. The 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1× GlutaMax, and 1× penicillin/ streptomycin.

Cell Hybrids.

For ES cell plus NPC cocultures, 1.0 × 106 ES cells were plated onto preplated 1.0 × 106 NPCs, first for 2 h in NPC medium and then for 2 h in ES cell medium. The cells were then trypsinized and plated at 1/5 into gelatin plus laminin-treated p100 dishes in ES cell medium, without or with 1 mM BIO (Calbiochem), for different times. After 72 h, puromycin was added to the ES cell medium for hybrid selection.

Retroviral Infection and iPSC Generation.

Retroviral infection was performed as described previously (18), with minor modifications. pMX-based retroviral vectors (Addgene) encoding mouse complementary cDNA of Oct4 and Klf4 and pSUPER-shTcf3 were separately cotransfected with packaging helper plasmids into 293T cells using CalPhos mammalian transfection kits (Clontech). After 24 h, the medium was changed for fresh medium; 24, 48, and 72 h later, the virus supernatants were collected, and filtered through 0.45-μm filters. The virus was concentrated by ultracentrifugation. NPCs were seeded at a density of 7 × 104 cells per well in six-well plates and incubated with the concentrated virus for Oct4, Klf4, and shCtrl (1:1:1) or for Oct4, Klf4, and shTcf3 (1:1:1), supplemented with 6 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma) for 24 h in NPC medium. The transduction efficiencies were calculated with the pBABE-GFP control virus (by FACS) and quantitative real-time PCR. Subsequently, the medium was changed for fresh NPC medium, and the cells were cultured for a total of 3, 5, or 7 d. The cells were then trypsinized and counted, and 7 × 104 cells were replated in gelatin plus laminin p60 dishes with ES cell medium. After several weeks, puromycin (0.5 μg/mL) was added for 7–10 d. Resistant clones were picked and replated onto MEFs. The colonies were selected for expansion.

Other Methods.

Details of other procedures are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Casola, L. di Croce, T. Graf, and G. Testa for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript; L. Marucci, F. Mancuso, and G. Roma for statistical support; and J. Frade, F. Aulicino, L. Stojic, and U. Di Vicino for technical support. F.L. is funded by CP10/00445 Project “Miguel Servet” of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. We are grateful for support from European Research Council Grant 242630-RERE (to M.P.C.) and from HFSP Grant RGP0011/2010 (to M.P.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1017402108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hochedlinger K, Plath K. Epigenetic reprogramming and induced pluripotency. Development. 2009;136:509–523. doi: 10.1242/dev.020867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaenisch R, Young R. Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2008;132:567–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lluis F, Pedone E, Pepe S, Cosma MP. Periodic activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling enhances somatic cell reprogramming mediated by cell fusion. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:493–507. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marson A, et al. Wnt signaling promotes reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, et al. Generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of exogenous Sox2. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2992–3000. doi: 10.1002/stem.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppler S, Kavanagh CL. Wnt signalling: Variety at the core. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:385–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merrill BJ, Gat U, DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Tcf3 and Lef1 regulate lineage differentiation of multipotent stem cells in skin. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1688–1705. doi: 10.1101/gad.891401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira L, Yi F, Merrill BJ. Repression of Nanog gene transcription by Tcf3 limits embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7479–7491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00368-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Newman JJ, Kagey MH, Young RA. Tcf3 is an integral component of the core regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2008;22:746–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.1642408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikasa H, et al. Regulation of TCF3 by Wnt-dependent phosphorylation during vertebrate axis specification. Dev Cell. 2010;19:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi F, Pereira L, Merrill BJ. Tcf3 functions as a steady-state limiter of transcriptional programs of mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1951–1960. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lluis F, Pedone E, Pepe S, Cosma MP. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway tips the balance between apoptosis and reprograming of cell fusion hybrids. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1940–1949. doi: 10.1002/stem.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva J, Chambers I, Pollard S, Smith A. Nanog promotes transfer of pluripotency after cell fusion. Nature. 2006;441:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature04914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, Nakatsuji N, Tada T. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1553–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do JT, Schöler HR. Nuclei of embryonic stem cells reprogram somatic cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:941–949. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Phosphorylation of TCF proteins by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12093–12100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JB, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva J, et al. Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eminli S, Utikal J, Arnold K, Jaenisch R, Hochedlinger K. Reprogramming of neural progenitor cells into induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of exogenous Sox2 expression. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2467–2474. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tam WL, et al. T-cell factor 3 regulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal by the transcriptional control of multiple lineage pathways. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2019–2031. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willert K, Jones KA. Wnt signaling: Is the party in the nucleus? Genes Dev. 2006;20:1394–1404. doi: 10.1101/gad.1424006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira CF, et al. ESCs require PRC2 to direct the successful reprogramming of differentiated cells toward pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhutani N, et al. Reprogramming towards pluripotency requires AID-dependent DNA demethylation. Nature. 2010;463:1042–1047. doi: 10.1038/nature08752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly KF, et al. -catenin enhances Oct-4 activity and reinforces pluripotency through a TCF-independent mechanism. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singhal N, et al. Chromatin-Remodeling Components of the BAF Complex Facilitate Reprogramming. Cell. 2010;141:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conti L, et al. Niche-independent symmetrical self-renewal of a mammalian tissue stem cell. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill BJ, et al. Tcf3: A transcriptional regulator of axis induction in the early embryo. Development. 2004;131:263–274. doi: 10.1242/dev.00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.