Abstract

In this grounded theory study, a theoretical framework that depicts the process by which childhood sexual abuse (CSA) influences the sexuality of women and men survivors was constructed. Data were drawn from interview transcripts of 95 men and women who experienced CSA. Using constant comparison analysis, the researchers determined that the central phenomenon of the data was a process labeled Determining My Sexual Being, in which survivors moved from grappling with questions related to the nature, cause, and sexual effects of the abuse to laying claim to their own sexuality. Clinical implications are discussed.

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is a significant public health problem that affects the lives of millions of people every year [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2004]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (1999) indicates that sexual abuse occurs when “a child is engaged in sexual activities that the child cannot comprehend, for which the child is developmentally unprepared and cannot give informed consent, and/or that violate the law or social taboos of society” (p.186). According to the United Nations (UN) Study on Violence [World Health Organization (WHO), 2006], 150 million girls and 73 million boys under the age of 18 experienced CSA worldwide in 2002. The Childhood Maltreatment Summary 2005 (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2007) estimates that 91,000 children were sexually abused in the United States in 2003.

Early reviews of the long-term effects of CSA on adult survivors indicated that CSA led to a variety of negative effects on adult survivors, including many negative sexual health outcomes (Beitchman et al., 1992; Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990; Polusny, & Follette, 1995). The negative effects of CSA on adult survivors have been debated, however, and some experts have argued that a dysfunctional family environment, rather than CSA, contributes to negative sequelae. This debate was most notable following the publication of two meta-analytic reviews of the negative effects of CSA on adult survivors (Rind & Tromovitch, 1997; Rind, Tromovitch, & Bauserman, 1998). In the first review of seven studies with national probability samples, the authors concluded, “CSA is not associated with pervasive harm and that harm, when it occurs, is not typically intense” (Rind & Tromovitch, p. 237). They also concluded that men are less likely to report negative effects than women. In the second review of 59 studies with college student samples, the authors concluded that students with a history of CSA were slightly less well-adjusted than those with no CSA history, that family environment explained more adjustment variance than CSA, and that the relationship between CSA and adjustment dissipated when family environment was statistically controlled (Rind, Tromovitch, & Bauserman). Men were again reported to have fewer negative effects. Two commentaries followed that critiqued the college student review on methodological and interpretive grounds. Ondersma and colleagues (2001) disputed the report's broad definition of CSA (e.g., the inclusion of noncontact events, such as a sexual proposition), the partialization of family environment based on quasi-experimental retrospective data, the focus on one index of harm (e.g., psychological effects in young adulthood), and the misinterpretation of small effect sizes to reflect little personal or social cost. Dallam and colleagues (2001) argued that sampling bias, the failure to operationalize CSA, the omission of relevant outcome measures (e.g., revictimization), the failure to correct for statistical attenuation and the misreporting of original data led to a minimization of the CSA-adjustment relationship.

Since the Rind controversy, however, several well-designed studies have indicated that, in fact, CSA is associated with a number of long-term effects, including those related to sexual health. Luo, Parish, & Laumann (2008) conducted a computer-assisted survey with a national, stratified probability sample of 1,519 women and 1,475 men between the ages of 20 and 64 in urban China to examine the relationship between childhood sexual contact before the age of 14 and sexual well-being in adulthood. Childhood sexual contact, reported by 5.1% of the men and 3.3% of the women, was associated with a variety of sexual consequences, including hyper-sexual behavior, adult sexual victimization, and sexual problems that included genitor-urinary symptoms, STIs, and sexual dysfunction. In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a national survey of 20,000 youth from 132 schools identified by stratified random sampling, participants were followed for three waves of data collection from 1995 to 2001. In order to examine childhood predictors of subsequent sexually coercive behavior (Casey, Beadnell, & Lindhorst, 2008), data from a sub-group of 5,649 young heterosexual adult males who participated in the third wave of interviews, and who had engaged in vaginal sex at least once, were examined. Path analysis revealed that a history of sexual abuse was significantly associated with sexual coercive behavior in adulthood (Unstandardized b = .41, p ≤ .001); this relationship is partially mediated by early sexual initiation. Wilson and Widom (2008) used a prospective cohort design to compare risky sexual behavior and HIV in adults with a documented history of childhood maltreatment with matched controls. Early sexual contact, prostitution, and promiscuity were assessed in individuals at age 29 (n=1,196), and HIV screening was conducted in individuals at 41 years of age (n=631). Childhood maltreatment was associated with prostitution and early sexual contact, and the prevalence of HIV infection in the maltreatment group was twice that in controls (although not statistically significant). Sexual abuse was associated with early sexual contact (OR = 1.75, p ≤ .001) and prostitution (OR = 2.38, p ≤ .05).

While researchers have focused on identifying specific negative sexual outcomes of CSA, little is known about how CSA influences sexual development. This study was designed to construct a theoretical framework that depicts the process by which CSA influences the lifelong sexuality of female and male survivors.

Methods

Grounded theory, a research methodology based on symbolic interactionism, pragmatism, and social psychology (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), was used to construct the theoretical framework. In grounded theory, researchers systematically gather and analyze data about social phenomena and develop hypotheses about relationships among concepts (Strauss & Corbin, 1994). Constant comparative analysis, a process in which data collection, analysis, and synthesis occur simultaneously, is used to facilitate theory generation about social or psychological processes that individuals experience in response to a common challenge (Strauss & Corbin, 1994). Grounded theory was selected to guide this study as the researchers believe that the best way to understand how CSA influences sexuality is to uncover the common psychosocial processes used by survivors in response to the CSA. Data are drawn from a larger, on-going qualitative research project (referred to as the parent study) entitled “Women's and Men's Responses to Sexual Violence.”

The Parent Study: Women's and Men's Responses to Sexual Violence

The purpose of the parent study is to develop a midrange theory that describes, explains and predicts women's and men's responses to sexual violence. The sample of the parent study consisted of 57 men and 64 women (n=121) who met the following inclusion criteria: (a) were aged 18 or older, (b) experienced sexual violence at some time in their lives, (c) screened negative for experiencing serious emotional problems within the past year, and (d) screened negative for current involvement in an abusive relationship that would make participation in the study dangerous. Participants were recruited in the community through the process of adaptive sampling (Martsolf, Courey, Chapman, Draucker, & Mims 2006). After IRB approval was obtained from the researchers' university, research associates canvassed communities, met with community leaders and members, and posted flyers throughout each of 14 socioeconomically-diverse communities. Participants called a toll-free number to express interest in participating and were screened against the study's inclusion criteria. Those who met criteria were interviewed in private settings in the community.

The participants signed an informed consent document and completed a demographic data sheet. They then completed open-ended interviews in which they were asked to describe the sexual violence they had experienced, what was happening in their lives at the time of the violence, how they managed following the violence, how the violence affected their lives, and how they healed, coped or recovered from the violence. Participants were paid $35.00 for each interview to compensate for their time and transportation costs.

The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed, and data were entered in the NVivo 6 qualitative computer software program (QSR, 2002). The data from all the transcripts were analyzed using constant comparison methods (Glaser, 1978) by a team of nurse researchers led by the second and third authors. The analysis initially consisted of a close, line-by-line reading of the transcripts, identification of codes used to group similar empirical indicators of important incidents or experiences, and uncovering of potential categories. Emerging categories deemed to be salient to the study aims and supported by robust data were assigned to individual team members for further exploration. One such category was tentatively labeled as “sexuality” because most participants discussed a myriad of ways in which sexual violence had affected their sexual development, identity, behaviors, and attitudes. The first author was assigned to guide the development of this category. The team determined that those participants who had experienced childhood sexual abuse, as opposed to adult sexual assault only, had unique responses related to sexuality; the framework of this study was, therefore, based on data from only those participants who had experienced sexual violence as children.

The Current Study: The Sexuality of Childhood Sexual Abuse Survivors

Sample

Ninety-five of the 121 participants in the parent study had experienced sexual violence in childhood and, therefore, constituted the sample for the current study. Forty-eight of these 95 participants were women and 47 were men. Twenty-four of the women were African American, 19 were Caucasian, 2 were multi-racial, and 3 did not report race. Nineteen of the men were Caucasian, 17 were African American, 4 were multi-racial, 1 was Asian, 1 was Hispanic, and 5 did not report race. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 62; 53 were single, 17 were married, 16 were separated or divorced, 7 did not report marital status, and 1 indicated being partnered. Sixty-five (65) participants were employed in a variety of occupations, including sales, service, education, health care, and construction. Eighteen of the participants were unemployed, 10 were students, and 2 were retired. About half (n = 49) reported an income under $10,000/year, 17 reported incomes between $10,000 and $30,000/year, 12 reported incomes between $30,000 and $50,000/year, 11 reported incomes above $50,000/year, and 7 did not report income.

Data Analysis

Data related to any aspects of sexuality (e.g., sexual development, identity, behaviors, relationships, attitudes) were highlighted on the 95 transcripts. Applicable text units (e.g., incidents, stories, ideas) were assigned codes to capture the meaning of the text and a list of relevant codes was developed. Some preliminary codes included sexually transmitted infections, sexual self-esteem, promiscuity, celibacy, looking for love, trading sex for money, trading sex for love, and sexual normality. Through constant comparison analysis (Glaser, 1978), the team combined the codes into higher level categories. Constant comparison analysis differs from the more commonly used approach of content analysis, in which data are at a low level of inference, coding is done at a descriptive level, data are organized into a taxonomy, inter-rater coding reliability is calculated, and the number of empirical indicators coded to each category are tabulated (Morse & Richards, 2002). In contrast, in constant comparison analysis, data are at a high level of inference, coding is done at an abstract level, and data are organized into a theoretical framework. Underlying uniformities in the data are determined through on-going discussions by a team of researchers, not to ensure coding reliability, but to obtain multiple, diverse perspectives for category development. Emerging categories are compared to additional empirical indicators for verification and refinement (Schwandt, 2001). Categories are considered saturated when they are fully explicated and on-going data collection fails to reveal new properties (Schreiber, 2001).

The theoretical relationships among the categories were determined, also by constant comparison analysis conducted in team meetings, and used to develop the framework. In grounded theory, the theoretical framework includes the identification of a psychosocial problem, which is the main concern of a group of people with a shared life challenge (e.g., CSA), and a psychosocial process, which is the way in which a group resolves or responds to that problem (Schreiber, 2001). Data analysis continued until all the categories were saturated and the framework was well-developed.

Findings

The majority of the participants described aspects of their sexuality that were influenced in some way by their CSA experiences. Many indicated that their abuse caused them to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors, such as having sex at an early age, having many sexual partners, having frequent or unprotected sex, and having sex while using drugs or alcohol to excess. Some referred to themselves as “promiscuous” because they had many sexual partners or frequently had sex with partners they barely knew. Several reported contracting STIs as a result of engaging in high-risk behaviors. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia were more likely to be reported by women, and HIV/AIDS were more likely to be reported by men. Several women and men said they became prostitutes to escape the abuse or an adverse family life; others spoke of trading sex for drugs and money as a way to “survive on the streets.” Several men revealed that as adolescents they served as a sexual partner for an adult man in return for attention, affection, or material support. A few participants, especially men, reported falling in love with the adult who abused them and being devastated when the relationship ended.

Many participants indicated that the CSA influenced how they came to view themselves as sexual beings. They talked about experiencing shame, confusion, and low self-esteem with regards to their sexuality. Many engaged in sex because they felt it was the only way they would find love. Women were especially likely to avoid intimate relationships because they were fearful and distrustful of men. A few men and women indicated that they had experienced confusion about their sexual orientation and attributed the confusion to the CSA.

The Theoretical Framework

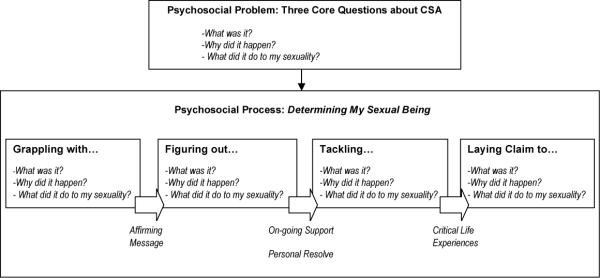

The theoretical framework that was developed by the team to reflect the process by which CSA influences the sexuality of survivors of CSA is displayed in Figure 1. The psychosocial problem shared by the participants - the need to answer three core questions about the abuse - is depicted in the box at the top of the figure. The psychosocial process the participants used in response to this problem, labeled Determining My Sexual Being, is depicted in the larger box below. The four phases that constitute this process are depicted in horizontal boxes connected by one-way arrows used to reflect the dynamic and generally progressive nature of the phases. Factors that facilitated the participants' transitions from one phase to another are depicted below each arrow. Not all participants described all four phases; as in any staged development model, most participants described the earliest phase (grappling), and fewest described the final phase (laying claim).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for Determining my Sexual Being

Psychosocial Problem: Three Core Questions About the CSA

The team determined that the common concern of the participants in regards to their sexuality was the need to understand the nature, cause, and sexual effects of the abuse by answering three core questions (See top box, Figure 1). The first core question was about to the nature of the abuse: “What was it?” Because the abuse occurred during childhood, the participants were disturbed and confused about the sexual activities, questioning what to call them, whether they were normal, and if they constituted “abuse” or “something else.” The second core question was about the cause of the abuse: “Why did it happen?” As the perpetrator was most often someone that the participants should have been able to trust, they questioned why the perpetrator had hurt them or why they were chosen or singled out for the sexual activities. The third core question was about the sexual effects of the abuse: “What did it do to my sexuality?” Because the abuse was sexual in nature, the participants questioned its influence on their sexual development, which was central to how they viewed themselves as men or woman. Although these core questions arose in childhood, most of the participants sought answers well into adulthood.

Psychosocial Process: Determining My Sexual Being

The team concluded that the participants, in response to their need to answer the three core questions, engaged in the psychosocial process we termed Determining My Sexual Being (See Figure 1). The term Determining [“to ascertain or establish in an exact way” (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2005, p. 462)] was chosen by the team because it incorporates both ascertaining and establishing answers to questions. The participants did not just attempt to find satisfactory answers to the three questions (ascertain); many also attempted to bring about or create (establish) the answers they sought. Their answers strongly influenced how they viewed all aspects of their sexual “being,” including both their sexual experiences and their identity as men or women. The four phases of the psychosocial process of Determining My Sexual Being are described below.

Grappling With… The process of Determining My Sexual Being begins with the phase of grappling with the answer to the three core questions. The term grapple with [“struggle with or work hard to overcome a difficulty or challenge” (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2005, p. 735)] captures the participants' descriptions of the effort, time, and frustration they experienced in trying to understand the abuse. Many indicated that despite much rumination, satisfactory answers eluded them, often for long periods of time. Even during the interviews, some participants wavered as they pondered the nature, cause, and effects of the CSA.

Most of the participants indicated that they experienced the sexual activities forced on them as children as “strange” and highly disturbing. Those who were very young did not know that the activities constituted “sex.” Most questioned whether the activities were “normal.” Many initially assumed the CSA was normal because other children in their families or in their neighborhoods were having similar experiences, whereas others thought it was normal because their perpetrators insisted that “everybody does this.” One 42-year-old man, who experienced CSA by his brothers, stated, “It seemed like it was a normal thing, then I enjoyed it, then, I mean, it's like a normal…. I don't know if it, if it, I didn't know any better.” A few participants were told by the perpetrator that this was a “teaching experience” to help prepare them for adult sexual intercourse. Some participants, especially those who were adolescents, experienced the sexual activities as physically pleasurable and therefore questioned whether the activities had been “mutual” or abuse. Some perpetrators indicated that the abuse was an expression of love. One 43-year old woman who had experienced CSA by her step-grandfather explained, “I was four or five years old, my grandfather used to call me his squaw. I had really long dark hair. He'd braid my hair… That was his way of getting my clothes off.” Because the explanations that the sexual activities were normal, educational, or loving often did not “ring true” with the participants, especially as they grew older, they continued to struggle to understand what happened to them. Many indicated that they continued to wrestle with “what it was” as adults. After relating accounts of CSA in the study interview, a few inquired of the researcher, “Do you think that that was abuse?”

Participants also grappled with the cause of the abuse; they asked why the abuse occurred and, more specifically, why it happened to them. Most notably, the majority struggled with whether the abuse was their fault. Many perpetrators, and some family members, suggested that the participants had been seductive or disobedient and therefore deserved the abuse. One 20-year-old man, who experienced CSA by both strangers and acquaintances, said, “I thought that it was something with me. Was it something that I was?…. Was it me, am I causing this?” Some participants continued to attempt to understand what caused the abuse, and especially whether they were to blame for it, well into adulthood. Even those who suspected that the abuse was the responsibility of the perpetrator continued to wrestle with whether they played a role.

Many participants grappled with understanding the sexual effects of the CSA as they pondered how it affected their sexuality. They questioned whether the abuse accounted for their sexual problems, contributed to their sexual orientation, or caused their relationship and intimacy issues. The man abused by his older neighbor stated, “I was confused … confused about maleness and femaleness.” Some participants agonized over whether the abuse caused “permanent damage.” A woman (age not reported), who experienced CSA by her male cousin, grappled with the effects of the abuse in the interview:

When I hit 14 or so I would have thoughts of other women, of having sexual experiences, [with] other women. I did, I acted upon that…. I guess it was experimentation…. Afterwards I always felt dirty and embarrassed and there for a long time I felt it was OK. It was, I don't know, I thought it was OK. I still like men, too, but I don't know.

Transition to the next stage was facilitated if someone important to the participant, such as a professional, partner, or family member, provided the message that abuse was not normal, was not done out of concern for the child's development or need for love, and was the fault of the perpetrator(s). Such affirming messages allowed the participants to move on in their quest to understand the abuse. Some participants did not receive such messages, either because the participants kept the abuse a secret or because others to whom they had disclosed the abuse responded in ways that were dismissing, blaming, or disbelieving. These participants continued to grapple with the core questions.

Figuring out… The process of Determining My Sexual Being continued for some participants with the phase of figuring out the answers to the three core questions. The term figure out [“solve or discover the cause of the problem” (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2005. p. 626)] captures the participants' descriptions of how they came to grasp the nature, cause, and effects of the abuse. Their answers “made sense” to them and helped them understand the abuse and how it affected their lives. The participants often experienced a sense of relief during this phase because they had grappled with the core questions for so long.

Many of the participants had figured out that the sexual activities they had been exposed to were abuse rather than a normal occurrence or a loving gesture. One 49-year-old woman who experienced CSA by a number of perpetrators, including her grandfather, uncle, and brother, stated, “I was in the seventh grade in school because they started teaching at that time, they started … in health, about the body and stuff. And I was in seventh grade when I started realizing these things was wrong.” For some, this realization occurred later in life. A 47-year-old woman, who had experienced CSA by her male cousin, realized her experiences constituted abuse after she talked with her social work instructor.

Many participants had also figured out why the abuse happened. They rejected the notion that the CSA was their fault, having come to believe that the blame rested on the perpetrator who abused them, the parents or caretakers who did not protect them, or a society or community that “failed to notice.” Many participants figured out that the perpetrators were “sick,” “evil,” or “perverted,” or had been abused themselves and were doing what they had been taught. One woman, who was sexually abused at age 12 by a church group leader, stated, “He (the church leader) was sick. When I got older and understood and found out what molesting a child was…. They say that the person that does do damage to the victim, that they're sick.” Some figured out that the sexual abuse had been going on in their families or communities for generations. One 50-year-old man, who was molested by a male friend of his family, stated, “Everybody else in the family … had all been molested by an uncle. My uncle was molesting two of my cousins and the family knew about it. Yea, the whole family knew about it …this is multigenerational.”

Many of the participants also figured out how the CSA had affected their sexuality. Some decided that their propensity to have casual sex or sex with older partners was related to the CSA. A 47-year-old woman, who experienced multiple episodes of CSA between the ages of 5 and 18 by her step-father, stated, “I would just kind of sleep around … the promiscuity was one of the symptoms [of the CSA] that … I realized.” Several female participants realized abuse caused them to “look for love in all the wrong places.” Some participants connected their disinterest in sex or an aversion to a particular sexual activity with their abuse. A few believed that their sexual orientation was related to the abuse. A 42-year-old man, who experienced CSA by his brothers, stated, “I'm gay … so that's probably why…. Cause what happened when I was younger [the sexual abuse].” Other participants were convinced there was no relationship between their sexual orientation and their CSA. Some participants figured out that their experiences with abuse had caused them to become perpetrators. A 36-year-old man, who was sexually abused by his older brother, stated, “I went on to do the same thing to my little brother.”

Transition to the next phase was facilitated by resources available to the participants, especially enduring relationships that were supportive and personal resilience. Participants moved from understanding the impact of CSA to making life changes because they had connections to others who supported the participants' progress. The connections were with friends, family members, professionals (often a therapist), or a Higher Being. In addition, participants indicated that this transition was facilitated by their own personal characteristics; they spoke of needing to be resilient, courageous, or tenacious to take this next step.

Tackling… The process of Determining My Sexual Being continued for some participants with the phase of tackling. The term tackle [“make determined efforts to deal with a problem or difficult task” (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2005. p. 1717)] was selected to capture the participants' descriptions of how they took what they had figured out about the abuse, accepted it with conviction, and worked hard to use these insights to change their lives.

Once the participants had figured out that they had been abused and were not at fault, they sought to gain more insight about the abuse and its effects. They sought opportunities to better understanding the phenomenon of CSA, the disturbances of perpetrators, the family dynamics that provide the context of the abuse, and the community factors that enabled it. Many sought therapy, but others “processed” the abuse with a close friend, family member, or clergy. Although tackling “issues” related to the abuse was hard and often painful work, the participants ultimately experienced a sense of relief or catharsis. A 54-year-old Hispanic male, who had been sexually abused by foster brothers, his mother, and older boys, had realized that the abuse was a “mess, … a cycle that becomes overwhelming” but revealed that he had tackled his abuse issues by doing “intense analysis.” He explained, “I read every book, I worked on myself.” A 37-year-old man, who was abused by an older cousin, used the research interview to begin the tackling process. He said the interview “was a stepping stone to a deeper realization – a deeper introspection.”

Fortified with new knowledge, participants struggled to improve their lives by changing their sexual behaviors, improving their intimate relationships, and refocusing their energies on healing. They took steps to become healthier physically and emotionally and to ameliorate sexual problems that they believed to be tied to the abuse. One 47-year-old woman, who had experienced CSA by her stepfather, stated, “Giving myself the space when I need the emotional tune up and I need down time. I enrolled at the gym, I exercise, I try to eat healthy. I am going out and doing things for me because I like that.” A number of participants began to practice safe sex practices and avoid high-risk behaviors. A 55-year-old man, who was abused and possibly infected with HIV by his uncle, said, “Getting infected it changed my whole life. It changed my whole life style. I stopped drinking alcohol. I'm not sexually active.”

What most often facilitated transition to the next phase was a particularly significant or powerful life experience. The participants who moved into the last phase of the process of Determining My Sexual Being typically had experienced a “turning point” that led to new feelings of empowerment, spiritual transformation, or peace and well-being. The event could have negative (e.g., a particularly severe assault or the abuse of their child), positive (e.g., a moving spiritual awakening), or developmental (e.g., the birth of a child).

Laying Claim To

The process of Determining My Sexual Being continued for a few participants with the phase of laying claim to the answers to the three core questions. The term laying claim to [“assert that one has a right to something; assert that one possesses a skill or quality” (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2005, p. 960)] describes instances in which the participants asserted their right to determine the nature, cause, and effects of the abuse; by doing so, they claimed the right to determine their sexuality. In this phase, the participants confidently acknowledged their own personal strengths and resolve. In several instances, their resolve extended beyond themselves and encompassed the act of laying claim for others.

A few participants claimed their right to label the nature and identify the cause of the abuse by proclaiming to others, either in interpersonal or public settings, that what happened to them as children was abuse and was not their fault. A 62-year-old man, who had contracted HIV/AIDS as a result of CSA, for example, became a victim spokesperson for his state's health department. He stated, “I started going …all over doing HIV presentations … trying to teach somebody about life, telling them what happened to me and how my life ended up … I was able to give something other than being taken, like the molestation.” By abdicating blame for the abuse, participants were freed to change their life course. A 25-year-old woman, who was molested at the age of 9 by her grandfather, stated, “I decided at one point that I was never going to let what he did destroy any aspect of my life because if I did that he would win.” Another 25-year-old woman who experienced CSA by a male neighbor and other adults stated, “I'm not responsible for what those men did to me. I am responsible for how I react and what I do with my life.” This woman chose to end her relationships with friends who abused drugs, surrounded herself with supportive women in a church group, and prepared to become a good mother to her unborn child.

Some participants proclaimed that they were entitled to good lives and could experience the sexuality they desired. A few chose temporary celibacy as a way to claim their right to determine when and with whom they would have sex. A 40-year-old woman, who was molested by a church youth leader and experienced abuse by two intimate partners as an adult, stated, “I just reached a point where I said I am sick of living, being promiscuous, being a pushover. At that point, I found my strength and I had some very good friends that helped me through all that.” Others asserted their rights within their current relationships. One 47-year-old woman, who was abused by her cousin, father, and brother, said, “I would stay (in relationships) because I wanted to please them [men]. Now I don't worry so much about pleasing them, I'm worried about how I feel….I worry about if it is good for me.” Some participants claimed the right to appear or dress as they pleased. One women, who indicated that she became a tomboy in response to abuse by her brother at the age of 10, indicated that she now “feels more ladylike…. Now, I find that I do want to be a woman. I am a woman.”

Some participants extended the process of laying claim by supporting an abuse-free life for others. A few spoke of becoming involved in anti-abuse advocacy groups and others described taking action to prevent children from being abused. One 40-year-old woman, who heard that her perpetrator was imprisoned for other assaults and was up for parole, contacted the parole authorities, She said, “I just happened to go to the state penitentiary (web) site and there he is in prison for raping his two daughters…. I did write to the parole board… I don't want this to happen to anyone else.”

Discussion

The purpose of this grounded theory study was to examine the process by which CSA influences the sexuality of women and men survivors throughout their lives. The analysis revealed that all the participants grappled with three core questions about the abuse: what it was, why it happened, and what it did to their sexuality. Many participants figured out that what happened to them was abuse and was not their fault, but it resulted in negative sexual effects. Some participants tackled the abuse through concerted efforts to understand it in a deeper way, to appreciate the connection between the abuse and their current problems, and to take action based on their new views. A few participants asserted their right to determine the nature, cause, and effects of the abuse, as well as their right to determine their own sexuality.

Participants typically went through the phases in a linear fashion, as depicted in the model. Several, however, experienced two stages simultaneously or reverted to a prior phase following a significant life event. For example, a participant might tackle a sexual problem while still figuring out that the abuse was not his/her fault or might lay claim to an abuse-free life but later tackle the effects of the abuse when a relationship proved unhealthy. The model, therefore, reflects a common trajectory for determining one's sexual being following childhood sexual abuse; the participants' narratives, however, reflect a rich variety of ways in which one might move from CSA to laying claim to one's sexuality.

The findings of this study resonate with several other studies that examine how CSA survivors recover or heal from the experience. For example, Denov's (2004) finding that female CSA survivors struggle with their sense of self-concept and self-identity in relationship to their femininity is consistent with our phase of grappling. O'Dougherty, Wright, Crawford, and Sebastian (2007) reported that positive resolution of CSA involved a stage of “increasing knowledge of sexual abuse.” This stage, which entailed a recognition that what happened was sexual abuse and that it was attributable to family dynamics, was similar to our phase of figuring out what it was and why it happened. The phase of tackling in the current study most closely resembles a phase identified by Draucker and Petrovic (1996), who compared the healing process of male CSA survivors to escaping a dungeon. They reported that once the men had “broken” free, they had to “journey to free soil.” Like tackling, this process entailed “the difficult, tedious, and threatening work of dealing with the abuse” …. involving “consistent hard work and persistence” (p. 328). Thomas & Hall (2008) found that women who experienced maltreatment in childhood but who thrived as adults discussed the process of “becoming resolute,” in which they exhibited a fierce determination to develop new healthy relationships. Becoming resolute shares many characteristics of laying claim.

The theoretical framework of Determining My Sexual Being can provide health care professionals who work with CSA survivors with a different way to conceptualize survivors' responses to CSA. Instead of focusing on a myriad of negative sexual outcomes, the framework emphasizes the process that survivors undergo as they move through the four stages on the way to laying claim to their sexuality. Clinicians' responses and interventions can be tailored to the stage that is most reflective of the survivors' current experiences. For example, two survivors who exhibit the same sexual negative outcomes might be in different phases of determining their sexual being, and therefore require different therapeutic approaches. A CSA survivor who engages in high-risk sexual behaviors but is still grappling to understand the abuse, for example, might first need help to figure out that he or she was abused, that the abuse was not his or her fault, and that the abuse can explain his or her behaviors. In contrast, another CSA survivor who engages in high-risk sexual behaviors, but has figured out the nature, cause, and effects of the abuse, might need to take actions to change the behaviors and assert his or her right to a healthy sexual life.

The major limitation of this study is that the data provided by the participants were mostly retrospective and their memories of actual events may be distorted. In addition, the interview questions were aimed broadly at all responses to sexual violence, rather than specifically at issues related to sexuality. Thus, the participants might have had sexual experiences that were not thoroughly explored during the interviews. Gathering more in-depth data about sexual responses may allow researchers to further develop the framework by identifying nuances in the process of Determining my Sexual Being. Additional data may, for example, may allow the researchers to determine ethnic differences in the process. The participants were primarily Caucasian and African American, and other ethnic groups were not well represented. Recruiting a more diverse sample, and asking questions aimed at exploring cultural and demographic influences would further advance the development of the framework.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research [R01.# NR08230-01A1]. Claire B. Draucker, PhD, Principal Investigator.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of children: subject review. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):186–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, DaCosta GA, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Beadnell B, Lindhorst TP. Predictors of sexually coercive behavior in a nationally representative sample of adolescent males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0886260508322198. Doi:10.1177/0886260508322198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(SS-02):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway Child Maltreatment 2005, Summary of Key Findings, Numbers and Trends. 2007 Retrieved 7/1/08 from http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/canstats.cf.

- Dallam SJ, Gleaves DH, Cepeda-Benito A, Silberg JL, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. The effects of child sexual abuse: Comment on Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;127(6):715–733. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denov MS. The long-term effects of child sexual abuse by female perpetrators: A qualitative study of male and female victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(10):1137–56. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker CB, Petrovic K. Healing of adult male survivors of childhood sexual abuse. IMAGE: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1996;28(4):325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1996.tb00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IS, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Sociology Press; Mill Valley, CA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Parish WL, Laumann EO. A population-based study of childhood sexual contact in China: Prevalence and long-term consequences. Child abuse and Neglect. 2008;32(7):721–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martsolf DS, Courey TJ, Chapman TR, Draucker CB, Mims BL. Adaptive sampling: Recruiting a diverse sample of survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2006;23(3):169–182. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2303_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Richards L. Readme first for a user's guide to qualitative research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- New Oxford American Dictionary. 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dougherty, Wright M, Crawford E, Sebastian K. Positive resolution of childhood sexual abuse experience: The role of coping, benefit-finding, and meaning-making. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ, Chaffin M, Berlinger L, Gordon I, Goodman GS, Barnett D. Sex with children is abuse: Comment on Rind, Tromovitch, and Bauserman (1998) Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(6):707–714. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. N6 (non-numerical unstructured data indexing searching & theorizing) qualitative data analysis program. Version 6 ed. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Follette VM. Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of empirical literature. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1995;4:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rind B, Tromovitch P. A meta-analytic review of findings from national samples of child sexual abuse. The Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34(3):237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. A meta-analytic examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse using college samples. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):22–53. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt TA. Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber RS. The “how to” of grounded theory: Avoiding the pitfalls. In: Schreiber RS, Stern PN, editors. Using grounded theory in nursing. Springer Publishing Company; New York, NY: 2001. pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology an overview. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TP, Hall JM. Life trajectories of female child abuse survivors thriving in adulthood. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(2):149–66. doi: 10.1177/1049732307312201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: A 30-year follow-up. Health and Psychology. 2008;27(2):149–58. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Report of the independent expert for the United Nations study on violence against children. 2006 Retrieved 6/16/08 from http://www.violencestudy.org/IMG/pdf/English.pdf.