Abstract

Background/Aims

We hypothesized that inflammatory markers are cross-sectionally and longitudinally associated with neuropsychological indicators of early ischemia and Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Framingham Offspring Study participants, free of clinical stroke or dementia (n = 1,878; 60 ± 9 years; 54% women), underwent neuropsychological assessment and ascertainment of 11 inflammatory markers. Follow-up neuropsychological assessments (6.3 ± 1.0 years) were conducted on 1,352 of the original 1,878 participants.

Results

Multivariable linear regression related the inflammatory markers to cross-sectional performance and longitudinal change in neuropsychological performances. Secondary models included a twelfth factor, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), available on a subset of the sample (n = 1,393 cross-sectional; n = 1,213 longitudinal). Results suggest a few modest cross-sectional inflammatory and neuropsychological associations, particularly for tests assessing visual organization (C-reactive protein, p = 0.007), and a few modest relations between inflammatory markers and neuropsychological change, particularly for executive functioning (TNF-α, p = 0.004). Secondary analyses suggested that inflammatory markers were cross-sectionally (TNF-α, p = 0.004) related to reading performance.

Conclusions

Our findings are largely negative, but suggest that specific inflammatory markers may have limited associations with poorer cognition and reading performance among community-dwelling adults. Because of multiple testing concerns, our limited positive findings are offered as hypothesis generating and require replication in other studies.

Key Words: Memory, Executive functioning, Inflammation, Cognition, WRAT-3 reading

Introduction

Inflammation is a well-known feature [1] and purported risk factor [2] for Alzheimer's disease (AD) perhaps because amyloid deposition stimulates neuroinflammatory processes with neurotoxic effects, contributing to the pathogenesis of AD [3,4]. Cerebrovascular disease is also associated with inflammation, as inflammatory cytokines predict incident stroke [5] and rise during acute stroke [6].

Though findings are mixed [7,8,9], some research has found that elevated inflammatory markers, including interleukin-6 [9,10,11,12,13], C-reactive protein (CRP) [9,10,14] and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1) [13], are associated with cognitive impairment. The purported mechanism accounting for past findings is that enhanced inflammatory processes are associated with the pathophysiology underlying cognitive decline (i.e. early AD or cerebrovascular changes).

The purpose of our study was to relate a large panel of systemic inflammatory biomarkers to detailed neuropsychological performances in a community-based cohort free of clinical dementia or stroke. Executive functioning measures are sensitive to cerebrovascular disease [15], and memory tests capture early AD neuropathology [16,17]. Therefore, we hypothesized inflammatory biomarkers would be most strongly associated with cross-sectional performances and longitudinal changes in memory and executive functioning relative to language and visual integration performances.

Methods

Participants

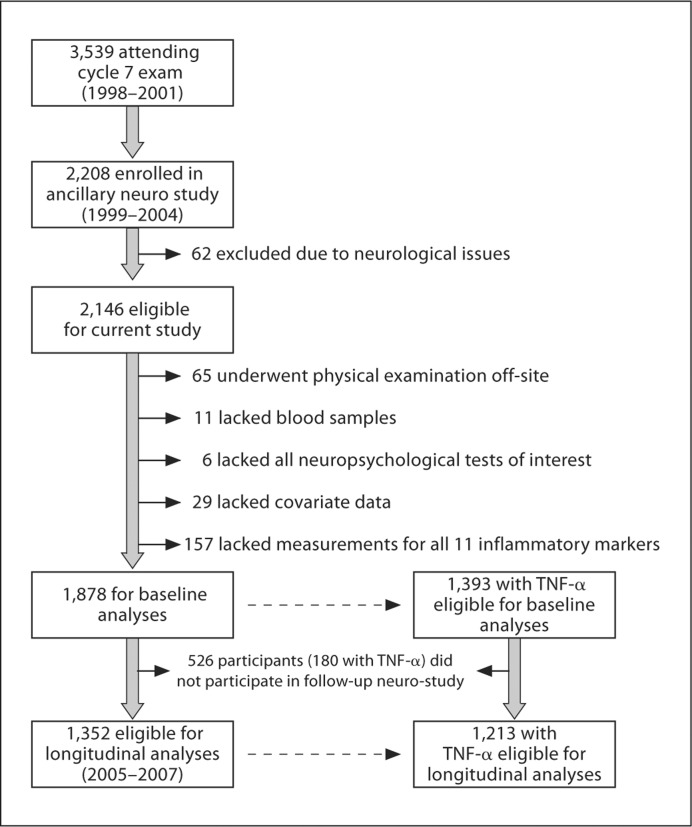

The Framingham Offspring Study design and selection criteria have been described elsewhere [18]. Briefly, 5,124 participants were recruited in 1971 and have been examined every 4–8 years since. From 1999 to 2004, participants who attended the seventh Offspring examination cycle (n = 3,539; 1998–2001) were invited to participate in an ancillary neuro-study, of which 2,208 enrolled. Participants with neurological conditions (e.g. dementia, clinical stroke, multiple sclerosis) were excluded from the present study (n = 62). Of 2,146 eligible participants, individuals were further excluded if they underwent physical examination off-site (n = 65), lacked blood samples (n = 11), all neuropsychological tests of interest (n = 6) or covariate data (n = 29), or they did not have all 11 inflammatory markers measured (n = 157). A twelfth marker, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was measured in a smaller sample later in the examination cycle. After exclusions, 1,878 participants were included, 1,393 of whom had TNF-α data. Between 2005 and 2007, 1,352 participants returned for a repeat neuro-study visit, 1,213 of whom had TNF-α data from the seventh offspring examination cycle (see fig. 1 for details). The Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Participants provided written informed consent prior to examination.

Fig. 1.

Participant enrollment and exclusion details.

Clinical covariates were classified at the seventh examination cycle. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were the means of two measurements. Current smoking (yes/no within the year prior to examination seven) and medication use were ascertained by self-report. Diabetes mellitus was defined as previous/current fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl or previous/current use of oral hypoglycemic or insulin. Prior cardiovascular disease (CVD; i.e. coronary heart disease, heart failure, intermittent claudication) information was obtained via medical histories and physical examinations conducted by the study and hospitalization and personal physician records. Three investigators adjudicated CVD events using reported criteria [19].

Neuropsychological Protocol

As previously described [20], participants completed a protocol based on measures administered to the original cohort over 25 years ago. Though newer versions of some tests exist, the study continues to use the Original versions to capitalize on the longitudinal nature of the Framingham Heart Study, allowing for temporal trend and cross-generational cognitive comparisons. In more recent examinations (1999 onward), tests were added to assess cognitive domains not adequately captured by the original protocol. A description of measures is provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological protocol description

| Domain | Neuropsychological test | Test description | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal memory | WMS logical memory delayed recall [45] | Measures delayed learning and memory for contextual information contained in two paragraph-length stories. | 0–24 |

| Visuospatial memory | WMS visual reproductions delayed recall [45] | Test of delayed learning and memory for novel shapes and designs. | 0–14 |

| Executive functioning | Trail making test, part B minus part A [46] | Measures sequencing reflected as a difference score between a visual scanning measure (part A) and set-shifting abilities through the alternation of connecting numbers and letters (part B); higher scores denote worse performance. | −360 to 360a |

| Language | BNT-30 item [47] | Assesses naming and lexical retrieval abilities via an abbreviated version of the original 60-item BNT. | 0–30 |

| Visuoperceptual abilities | Hooper visual organization test [48] | A measure of object recognition; participants mentally rearrange pieces of objects to identify the target stimulus. | 0–30 |

| Verbal reasoning | WAIS similarities subtest [49] | A measure of verbal reasoning and abstraction. | 0–26 |

| Reading | WRAT-3 reading subtest | A measure of reading for words with irregular sound-to-spelling correspondence. | 0–57 |

Possible range for both Trail making test part A and part B is 360 s, so the difference score between these measures could range from −360 to 360 s. WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale, BNT = Boston Naming Test, WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WRAT = Wide Range Achievement Test.

Inflammatory Markers

At cycle examination seven, 11 biomarkers (plus TNF-α on a subset) were measured representing a variety of pathways and phases of the inflammatory process [21]. The biomarkers and inflammatory pathway or phase assessed included: plasma CD40 ligand (inflammation, thrombosis), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) activity and mass (oxidative stress), osteoprotegerin (endothelial integrity, calcification), P-selectin (inflammation, cell adhesion), TNF receptor-II (TNFRII; cytokines) and TNF-α (cytokines), and serum CRP (acute phase reactant), ICAM1 (selectins), interleukin-6 (acute-phase reactant), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1; chemokines), and myeloperoxidase (oxidative antimicrobial defense). The intra-assay coefficients of variation were: CD40 ligand 4.4%, interleukin-6 3.1%, ICAM1 3.7%, Lp-PLA2 activity 7.9% (low) to 5.9% (high), LpPLA2 mass between 6.0 and 8.0%, MCP-1 3.8%, myeloperoxidase 3.0%, osteoprotegerin 3.7%, P-selectin 3.0%, TNF-α 7.6% (low control) to 5.6% (high control), and TNFRII 2.3%. The kappa statistic for 146 CRP samples run in duplicate was 0.95 [22].

Statistical Analyses

All inflammatory markers and a subset of neuropsychological scores (i.e. Trail making test part B minus part A, Boston naming test-30 item, Hooper visual organization test) were natural log-transformed to normalize distributions for analyses.

As previously described [23], neuropsychological scores were adjusted for age and education, separately by sex, to enable comparison across measures. Resulting values were standardized, separately by sex, to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (i.e. values were transformed to represent standard deviation units from the mean).

Multiple investigative groups have related different markers to individual neuropsychological measures [for example, see [9], [10]]; so, to allow cross-study comparisons, we used multivariable regression to assess the covariate-adjusted relations of each log-transformed inflammatory marker and individual neuropsychological test. Secondary analyses were conducted to assess effect modification of the cross-sectional relations by sex and age (<60 vs. ≥60 years based on the sample median and prior work [23,24]). We used multivariable regression to analyze the covariate-adjusted linear relations of each log-transformed inflammatory marker to annualized change in neuropsychological test performance over the follow-up period, which was computed as the unstandardized, untransformed neuropsychological measure from the beginning to the end of the follow-up period, divided by the number of years in the follow-up period. Neuropsychological tests were broken down into two categories, based on our a priori hypotheses. Primary measures hypothesized to have significant relations with the inflammatory markers consisted of memory (logical memory, visual reproduction) and executive function tests (Trail making test part B minus A, Similarities). Secondary measures consisted of language (Boston naming test-30 item), reading (WRAT-3 reading, a proxy measure for education quality [25,26,27] or cognitive reserve [28,29]) and visual integration tests (Hooper visual organization test) that we did not expect to be strongly associated with the inflammatory markers.

Covariates were selected a priori based on prior work [24,30,31,32] and included age, sex, education, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, total/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, current smoking, fasting glucose, triglycerides, diabetes, hypertension treatment, hormone replacement therapy, lipid-lowering treatment, aspirin (at least 3 days per week), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, atrial fibrillation, and prevalent CVD.

To modestly account for multiple testing, we a priori selected p < 0.01 to declare a significant linear relation as a balance between an overly conservative versus a more liberal approach for cross-sectional and longitudinal research. p values between 0.05 and 0.01 were considered borderline results. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Sample characteristics are provided in table 2. The participants’ mean age was 60 ± 9 years (35–85 years). Median and 25th to 75th percentile data are provided in table 3 for the untransformed inflammatory markers and the raw neuropsychological performances. Time to follow-up was 6.3 ± 1.0 years.

Table 2.

Baseline (examination seven) study sample clinical characteristics (n = 1,878)

| Age, years | 60 ± 9a |

| Female, % | 54 |

| Education, % | |

| 4th grade or less, % | 3 |

| >4th grade but not high school graduate, % | 31 |

| High school graduation/no college, % | 26 |

| At least some college, % | 40 |

| Time to baseline neuropsychological assessment years | 0.73 ± 0.71a |

| Neuropsychological follow-up period, years | 6.3 ± 1.0a |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 125 ± 18a |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 74 ± 9a |

| Body mass index | 27.9 ± 5.2a |

| Total/HDL cholesterol ratio | 4.1 ± 1.4a |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl | 103 ± 26a |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 134 ± 89a |

| Cigarette smoking, % | 12 |

| Diabetes, % | 12 |

| Hypertension treatment, % | 30 |

| Lipid lowering medication, % | 18 |

| Hormone replacement therapyb, % | 35 |

| Aspirin treatment, % | 32 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 3 |

| Prevalent CVDc, % | 10 |

Mean ± SD.

Percentage includes women only.

Prevalent CVD does not include clinical stroke.

Table 3.

Raw inflammatory marker and neuropsychological data (n = 1,878)

| Characteristic | Untransformed inflammatory markers |

|---|---|

| CD40 ligand, ng/ml | 1.3 (0.6, 3.9) |

| CRP, mg/l | 2.0 (0.9, 4.9) |

| ICAM1, ng/ml | 239 (209, 280) |

| Interleukin-6, pg/ml | 2.6 (1.8, 4.2) |

| MCP-1, pg/ml | 309 (253, 382) |

| Myeloperoxidase, ng/ml | 40.3 (28.1, 59.3) |

| Osteoprotegerin, pmol/1 | 5.4 (4.4, 6.4) |

| P-selectin, ng/ml | 36.1 (28.6, 45.0) |

| Lp-PLA2 activity, nmol/ml/min | 140 (118, 165) |

| Lp-PLA2 mass, ng/ml | 284 (228, 355) |

| TNFRII, pg/ml | 1,950 (1,654, 2,373) |

| TNF-αa, pg/ml | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) |

| Untransformed neuropsychological data | Untransformed neuropsychological annualized changeb | |

|---|---|---|

| Logical memory delayed, total | 11.0 (8.0, 13.0) | 0.12 (−0.30, 0.46) |

| Visual reproduction delayed, total | 8.0 (6.0, 11.0) | 0 (−0.34, 0.27) |

| Trail making test, part B minus part A | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.07) |

| Boston naming test-30 item, total | 28.0 (26.0, 29.0) | 0 (−0.15, 0.15) |

| Hooper visual organization test, total | 25.5 (24.0, 27.0) | 0 (−0.26, 0.16) |

| Similarities subtest, total | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | 0 (−0.31, 0.31) |

| WRAT-3 reading subtest, total | 49.0 (46.0, 53.0) | 0 (−0.17, 0.17) |

Values are expressed as median (25th, 75th percentile). WRAT = Wide Range Achievement Test.

TNF-α data are based on a subset of male (n = 662) and female (n = 731) participants.

Computed as the unstandardized, untransformed neuropsychological measure from the beginning to the end of the follow-up period, divided by the number of years in the follow-up period.

Inflammatory Markers and Cross-Sectional Performances

Inflammatory markers were unrelated to cross-sectional performances in learning, memory, information processing, and executive functioning (table 4). A few unexpected associations emerged between inflammatory markers and language (naming and verbal reasoning), visual integration, and reading performances (table 4). Specifically, associations were observed between CRP and Hooper visual organization test (β = −0.06, p = 0.007) and TNF-α and WRAT-3 reading performance (β = −0.68, p = 0.003). Two inflammatory markers were borderline significant in relation to Hooper visual organization test, including MCP-1 (β = −0.15, p = 0.04) and TNF-α (β = −0.11, p = 0.04). Two inflammatory markers were borderline significant in relation to WRAT-3 reading, including myeloperoxidase (β = −0.39, p = 0.02) and TNFRII (β = −0.79, p = 0.03). To gain a sense of the magnitude of the cross-sectional association, the TNF-α and WRAT-3 reading performance result is used as an example. WRAT-3 reading performance decreased, on average, by 0.68 per increase of one in log TNF-α (table 4), a magnitude similar to the mean decrease in WRAT-3 reading performance seen with an increase in age of approximately 10 years, as can be shown in a multivariable regression using the same covariates.

Table 4.

Multivariable-adjusted regression results of individual inflammatory markers and cross-sectional neuropsychological measures

| Logical memory delayeda |

Visual reproduction delayeda |

Trail making test, part B minus part Aa |

Hooper visual organization testb |

Boston naming test-30 itemb |

Similarities subtesta |

WRAT-3 readingb |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | |

| CD40 ligand | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.159 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.209 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.811 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.700 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.986 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.488 | −0.08 | −0.24 | 0.07 | 0.30 |

| CRP | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.111 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.596 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.384 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.008 | −0.00 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.913 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.163 | −0.18 | −0.38 | 0.01 | 0.069 |

| ICAM1 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.28 | 0.438 | −0.16 | −0.36 | 0.03 | 0.106 | −0.13 | −0.33 | 0.08 | 0.221 | −0.20 | −0.40 | 0.01 | 0.057 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 0.21 | 0.960 | −0.12 | −0.33 | 0.08 | 0.229 | −0.29 | −1.12 | 0.54 | 0.489 |

| Interleukin-6 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.107 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.520 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.243 | −0.03 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.352 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.782 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.096 | −0.24 | −0.53 | 0.04 | 0.097 |

| MCP-1 | −0.12 | −0.25 | 0.01 | 0.079 | −0.05 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.468 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.939 | −0.15 | −0.28 | −0.01 | 0.032 | −0.00 | −0.14 | 0.13 | 0.954 | −0.06 | −0.20 | 0.07 | 0.371 | −0.05 | −0.61 | 0.51 | 0.866 |

| Myeloperoxidase | −0.00 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.912 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.235 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.195 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.955 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.976 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.500 | −0.39 | −0.73 | −0.06 | 0.022 |

| Osteoprotegerin | −0.05 | −0.21 | 0.12 | 0.555 | −0.05 | −0.21 | 0.12 | 0.587 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.23 | 0.444 | −0.00 | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.971 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.20 | 0.737 | −0.08 | −0.25 | 0.09 | 0.350 | 0.10 | −0.59 | 0.80 | 0.766 |

| P-selectin | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.17 | 0.549 | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.11 | 0.801 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.23 | 0.115 | −0.03 | −0.16 | 0.10 | 0.611 | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.11 | 0.801 | −0.06 | −0.19 | 0.06 | 0.331 | −0.32 | −0.84 | 0.21 | 0.244 |

| Lp-PLA2 activity | −0.14 | −0.38 | 0.10 | 0.253 | −0.14 | −0.38 | 0.10 | 0.252 | −0.08 | −0.33 | 0.16 | 0.490 | −0.06 | −0.30 | 0.18 | 0.625 | 0.09 | −0.16 | 0.33 | 0.490 | 0.16 | −0.08 | 0.40 | 0.202 | −0.01 | −1.01 | 0.98 | 0.978 |

| Lp-PLA2 mass | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.910 | −0.07 | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.340 | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.11 | 0.635 | −0.02 | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.782 | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.20 | 0.540 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.19 | 0.575 | −0.22 | −0.83 | 0.39 | 0.478 |

| TNFRII | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.24 | 0.416 | −0.04 | −0.21 | 0.13 | 0.661 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.896 | −0.14 | −0.31 | 0.04 | 0.119 | −0.05 | −0.23 | 0.12 | 0.543 | −0.10 | −0.27 | 0.07 | 0.250 | −0.79 | −1.50 | −0.09 | 0.028 |

| TNF-αc | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.411 | −0.06 | −0.17 | 0.05 | 0.320 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.10 | 0.854 | −0.11 | −0.23 | 0.00 | 0.044 | −0.07 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 0.225 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.769 | −0.68 | −1.13 | −0.22 | 0.003 |

β = Estimated change in neuropsychological test performance as a function of a one standard deviation change in the specific inflammatory marker; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals for change value.

Primary neuropsychological measures hypothesized to have significant association with inflammatory markers.

Secondary neuropsychological measures for which no significant association was expected.

Analysis based on a smaller dataset (n = 1,393).

Effect Modification for Cross-Sectional Neuropsychological Performances

For WRAT-3 reading performance, there was a borderline significant interaction between sex and myeloperoxidase (p = 0.07). For Hooper visual organization test performance, there was a borderline significant interaction between sex and CRP (p = 0.04). In both cases, the direction of the marker effect for each sex was the same as that for both sexes combined, signifying that increasing inflammatory concentration was associated with lower neuropsychological performance. However, the magnitude of effect was larger for males than females, and the magnitude was also statistically significant for males but not for females. No other inflammatory markers manifested significant effect modification for the neuropsychological tests.

Inflammatory Markers and Longitudinal Neuropsychological Performances

Significant associations emerged between TNF-α and change in Trail making test part B minus part A (β = 0.04, p = 0.004; table 5). Borderline associations were observed between several additional inflammatory markers and change in Trail making test part B minus part A, including CD40 ligand (β = 0.01, p = 0.04), myeloperoxidase (β = 0.02, p = 0.02) and TNFRII (β = 0.04, p = 0.04).

Table 5.

Multivariable-adjusted regression results of individual inflammatory markers and longitudinal neuropsychological measures

| Logical memory delayeda |

Visual reproduction delayeda |

Trail making test, part B minus part Aa |

Hooper visual organization testb |

Boston naming test-30 itemb |

Similarities subtestb |

WRAT-3 readingb |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | β | 95% | CI | p value | |

| CD40 ligand | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.600 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.479 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.042 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.582 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.676 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.136 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.079 |

| CRP | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.297 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.648 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.629 | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.741 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.044 | −0.00 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.776 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.948 |

| ICAM1 | −0.04 | −0.20 | 0.13 | 0.666 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.050 | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.10 | 0.054 | −0.05 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.375 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.687 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.16 | 0.889 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.949 |

| Interleukin-6 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.388 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.316 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.342 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.382 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.064 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.855 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.685 |

| MCP-1 | 0.10 | −0.00 | 0.20 | 0.058 | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.463 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.726 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.748 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.516 | −0.03 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.460 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.425 |

| Myeloperoxidase | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.657 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.765 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.021 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.205 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.265 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.034 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.766 |

| Osteoprotegerin | −0.06 | −0.19 | 0.07 | 0.389 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.16 | 0.509 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.332 | −0.07 | −0.16 | 0.01 | 0.082 | −0.04 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.246 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.16 | 0.426 | −0.05 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.257 |

| P-selectin | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 0.199 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.545 | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.991 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.869 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.399 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.692 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.783 |

| Lp-PLA2 activity | −0.08 | −0.27 | 0.11 | 0.409 | −0.14 | −0.31 | 0.03 | 0.109 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.824 | −0.00 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.967 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.201 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.17 | 0.991 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.152 |

| Lp-PLA2 mass | −0.08 | −0.20 | 0.03 | 0.150 | −0.05 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.362 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.510 | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.03 | 0.272 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.085 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.251 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.922 |

| TNFRII | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.14 | 0.989 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.19 | 0.287 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.043 | −0.00 | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.987 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.931 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.708 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.922 |

| TNF-αc | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.606 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.941 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.004 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.821 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.636 | −0.08 | −0.16 | −0.00 | 0.046 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.634 |

β = Estimated change in neuropsychological test performance as a function of a one standard deviation change in the specific inflammatory marker; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals for change value.

Primary neuropsychological measures hypothesized to have significant association with inflammatory markers.

Secondary neuropsychological measures for which no significant association was expected.

Analysis based on a smaller dataset (n = 1,213).

A few unexpected associations emerged for language, including naming and verbal reasoning(table 5). Specifically, borderline associations were observed between CRP and change in Boston naming test-30 item (β = −0.02, p = 0.04), between myeloperoxidase and change in similarities (β = 0.06, p = 0.03), and between TNF-α and change in similarities (β = −0.08, p = 0.046).

To gain a sense of the magnitude of the association between inflammatory markers and annualized change in neuropsychological performances, the association between TNF-α and the annualized change in Trail making test part B minus part A is used as an example. The annualized change in Trail making test part B minus part A increased on average by 0.04 per increase of one in log TNF-α (table 4), a magnitude similar to the mean increase in annualized change in Trail making test part B minus part A seen with an increase in age of approximately 4 years, as can be shown in a multivariable regression with the same covariates.

Discussion

The present research represents a valuable benchmark study of cross-sectional and longitudinal inflammatory-cognitive relations, as the comprehensive dataset under examination provides robust, hypothesis-driven comparisons across numerous inflammatory markers and cognitive measures. The analytical plan implemented minimizes the potential positive publication bias of reporting isolated significant relations between one inflammatory marker and cognitive performances.

Specifically, we cross-sectionally and longitudinally examined a comprehensive panel of twelve inflammatory markers in relation to multiple neuropsychological performances in our community-based cohort free of clinical dementia or stroke. A conservative multiple testing adjustment applied to the current results would render all comparisons non-significant. Therefore, we applied a more modest adjustment, based on hypothesis-driven comparisons (i.e. primary vs. secondary neuropsychological variables of interest), and found relatively few significant associations. Cross-sectionally, CRP was significantly associated with a measure of visual integration, and MCP-1 and TNF-α were borderline associated with visual integration. Longitudinally, TNF-α was related to change in executive functioning, while CD40 ligand, myeloperoxidase, and TNFRII were borderline associated with executive functioning decline. Several additional borderline associations emerged, including myeloperoxidase and TNF-α in relation to verbal reasoning decline and CRP in relation to lexical retrieval decline. Our analyses are largely negative, and overall, findings suggest that within a relatively healthy community-dwelling sample with a wide age range, inflammation has a very limited association with cognitive impairment as contrasted with prior studies leveraging older cohorts [9,10,13,14].

Multiple mechanisms may account for the previously reported inflammatory marker-cognitive relations [9,10,13,14] and the very minimal cross-sectional and longitudinal associations reported here (assuming the associations are valid). First, animal models suggest inflammation may mediate pathophysiological processes affecting the central nervous system (CNS), including neuronal changes, astrocytosis, and proliferative angiopathy [33]. Inflammation is believed to play a role in conditions associated with advancing age known to impact CNS integrity, including cardiovascular [34], neurodegenerative [3,4], and cerebrovascular diseases [5,6]. Thus, multiple pathways may account for relations between inflammation and CNS injury, which is consistent with the diverse neuropsychological associations observed in the current study (e.g. visual integration, executive functioning, verbal reasoning) and prior work [9,10,13,14]. Specifically, those cognitive functions modestly related to inflammatory markers in the current study are subserved by multiple and varied neuroanatomic structures [17,35,36,37]. Therefore, inflammatory markers may affect global brain function, rather than just one specific neuroanatomic structure, which is consistent with prior work linking enhanced inflammatory markers to decreased totalbrain volume [24].

A novel but preliminary finding of the present study was that some inflammatory markers (including TNF-α, myeloperoxidase, and TNFRII) were modestly related to cross-sectional WRAT-3 reading performance. Reading performance is a purported marker of educational attainment [38] and education quality [25,26,27]. Significant relations have been reported between educational attainment and inflammatory markers, including CRP [39,40,41], interleukin-6 [39], ICAM1 [39], and MCP-1 [39]. Our preliminary findings extend prior work by demonstrating similar associations between inflammatory markers and a proxy measure of education quality (i.e. WRAT-3 reading subtest [25,26,27]). Mechanisms accounting for relations between inflammatory markers and the WRAT-3 reading subtest may include the higher prevalence of CVD [42] and poor health behaviors, such as smoking [43], among those with lower education levels.

The present findings must be considered in the context of some limitations. As mentioned above, we examined numerous models with multiple testing, raising the strong possibility of false positive findings. A strict Bonferroni correction for multiple testing would have rendered all findings statistically non-significant; however, because of the correlated nature of the markers and the neuropsychological tests, a strict Bonferroni correction might be too conservative. We acknowledge that our findings will need to be further replicated in the literature, particularly the association between inflammatory markers and reading performance. Second, the racial composition of the Framingham Offspring Study is predominantly white of European descent (>99%) and the participants were middle-aged to elderly, so the generalizability of the current results to other races, ethnicities, and age groups is unknown. Third, exclusion of institutionalized individuals and participants with clinical stroke and dementia resulted in a healthier sample, reducing the likelihood of detecting relations that may be present in the general population or in prior inflammatory-cognitive studies emphasizing older cohorts [7,8,9,10,11,14,44]. Reliance on older neuropsychological measures may also be a limitation. Also, by adjusting the neuropsychological variables a priori for age, sex, and education and including age, sex, and education as covariates, we may have ‘over-adjusted’ our models; however, we analyzed the data with and without the demographic covariates, and the findings were similar (data not shown). Finally, by accounting for multiple potential confounders, we may have ‘over-adjusted’ our models, as inflammation may predispose to neuropsychological impairment through intermediate mechanisms, such as hypertension, diabetes, and other risk factors.

Despite these limitations, our study has a number of strengths, including the large community-based cohort without clinical dementia or stroke, the broad participant age range spanning multiple decades, concurrent examination of twelve inflammatory biomarkers, comprehensive ascertainment of potential confounders, and stringent quality control procedures for the acquisition and measurement of inflammatory biomarkers and longitudinal neuropsychological variables. From a conservative standpoint, our positive findings may be viewed as hypothesis generating. If the modest positive inflammatory marker and neuropsychological relations reported here are replicated in external cohorts, they may provide evidence linking inflammation with visual integration, executive functioning, and reading performance.

References

- 1.Yasojima K, Schwab C, McGeer EG, et al. Human neurons generate C-reactive protein and amyloid P: upregulation in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2000;887:80–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02970-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Meijer J, et al. Inflammatory proteins in plasma and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:668–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:741–749. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammation, autotoxicity and Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarkowski E, Rosengren L, Blomstrand C, et al. Early intrathecal production of interleukin-6 predicts the size of brain lesion in stroke. Stroke. 1995;26:1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.8.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarkowski E, Rosengren L, Blomstrand C, et al. Intrathecal release of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines during stroke. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:492–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4621483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weuve J, Ridker PM, Cook NR, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cognitive function in older women. Epidemiology. 2006;17:183–189. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000198183.60572.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dik MG, Jonker C, Hack CE, et al. Serum inflammatory proteins and cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2005;64:1371–1377. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158281.08946.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schram MT, Euser SM, de Craen AJ, et al. Systemic markers of inflammation and cognitive decline in old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:708–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx BW, et al. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology. 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver JD, Huang MH, Albert M, et al. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology. 2002;59:371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright CB, Sacco RL, Rundek TR, et al. Interleukin-6 is associated with cognitive function: the Northern Manhattan Study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;15:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafnsson SB, Deary IJ, Smith FB, et al. Cognitive decline and markers of inflammation and hemostasis: the Edinburgh Artery Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:700–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teunissen CE, van Boxtel MP, Bosma H, et al. Inflammation markers in relation to cognition in a healthy aging population. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;134:142–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe N, Linn R, Babikian VL, et al. Frontal systems impairment following multiple lacunar infarcts. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:129–132. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530020025010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahn DA, Sullivan EV, Shear PK, et al. Structural MRI correlates of recognition memory in Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1998;4:106–114. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798001064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman ME, Pan JW, Hetherington HP, et al. Hippocampal neurochemistry, neuromorphometry, and verbal memory in nondemented older adults. Neurology. 2008;70:1594–1600. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306314.77311.be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, et al. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cupples L, D'Agostino R. Some risk factors related to the annual incidence of cardiovascular disease and death using pooled repeated biennial measurements: Framingham Study, 30-year follow-up. In: Kannel W, Polf P, Garrison R, editors. The Framingham Study: An Epidemiological Investigation of Cardiovascular Disease. Washington: National Institutes of Health; 1987. pp. 87–203. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Au R, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, et al. New norms for a new generation: cognitive performance in the Framingham offspring cohort. Exp Aging Res. 2004;30:333–358. doi: 10.1080/03610730490484380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnabel R, Larson MG, Dupuis J, et al. Relations of inflammatory biomarkers and common genetic variants with arterial stiffness and wave reflection. Hypertension. 2008;51:1651–1657. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.105668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathiresan S, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Contribution of clinical correlates and 13 C-reactive protein gene polymorphisms to inter-individual variability in serum C-reactive protein level. Circulation. 2006;113:1415–1423. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferson AL, Himali J, Beiser A, et al. Cardiac index is associated with brain aging: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122:690–697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.905091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Larson MG, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: The Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1032–1038. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257815.20548.df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedges L, Laine R, Greenwald R. Does money matter? A meta-analysis of studies of the effects of differential school inputs on student outcomes. Educ Res. 1994;23:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manly JJ, Byrd DA, Touradji P, et al. Acculturation, reading level, and neuropsychological test performance among African American elders. Appl Neuropsychol. 2004;11:37–46. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1101_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, et al. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:448–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang MX, et al. Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:680–690. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.680.14579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupuis J, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Genome scan of systemic biomarkers of vascular inflammation in the Framingham Heart Study: evidence for susceptibility loci on 1q. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 2004;35:1857–1861. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135226.53499.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology. 2004;63:1591–1599. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142968.22691.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E, et al. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10061–10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed BR, Eberling JL, Mungas D, et al. Memory failure has different mechanisms in subcortical stroke and Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:275–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moritz CH, Johnson SC, McMillan KM, et al. Functional MRI neuroanatomic correlates of the Hooper Visual Organization Test. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:939–947. doi: 10.1017/s1355617704107042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yochim B, Baldo J, Nelson A, et al. D-KEFS Trail Making Test performance in patients with lateral prefrontal cortex lesions. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:704–709. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warner MH, Ernst J, Townes BD, et al. Relationships between IQ and neuropsychological measures in neuropsychiatric populations: within-laboratory and cross-cultural replications using WAIS and WAIS-R. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1987;9:545–562. doi: 10.1080/01688638708410768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, Hayes LJ, et al. Association of educational level with inflammatory markers in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:622–628. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lubbock LA, Goh A, Ali S, et al. Relation of low socioeconomic status to C-reactive protein in patients with coronary heart disease (from The Heart and Soul Study) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1506–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos CE, Chrysohoou CA, et al. The association between educational status and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease in healthy individuals: the ATTICA study. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:188–194. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:48–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith GD, Hart C, Watt G, et al. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: the Renfrew and Paisley Study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1998;52:399–405. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimopoulos N, Piperi C, Salonicioti A, et al. Indices of low-grade chronic inflammation correlate with early cognitive deterioration in an elderly Greek population. Neurosci Lett. 2006;398:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler D. A standardized memory scale for clinical use. J Psychol. 1945;19:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hooper H. Hooper Visual Organization Test (HVOT) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]