Abstract

Background

A clear-cut need exists for safe and effective alternatives to the use of isotretinoin in severe acne. Lack of data regarding the specifics of isotretinoin’s mechanism of action has hampered progress in this area. Recently the protein neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) has been identified as a mediator of the apoptotic effect of isotretinoin on sebocytes. The goal of this paper is to further establish the clinical relevance of NGAL and to elucidate the factors that induce NGAL expression in sebocytes.

Methods/Results

Methods were developed to isolate and quantify skin surface levels of NGAL from normal subjects and acne patients undergoing treatment with isotretinoin. Acne patients were found to have higher skin levels of NGAL compared to normal subjects. Studies in SEB-1 sebocytes indicate that NGAL expression is increased in response to P. acnes and IL-1β. In patients, isotretinoin increases NGAL levels by 2.4-fold on the skin surface and this increase precedes decreases in sebum and P. acnes counts.

Conclusions

These data support the hypothesis that NGAL is an important mediator of the early effects of isotretinoin on the sebaceous glands and provide insights into the mechanisms that regulate NGAL expression in the skin.

Keywords: Acne, Isotretinoin, NGAL, P. acnes

Introduction

The dramatic effect of isotretinoin (13-cis retinoic acid, 13-cis RA) on acne was a fortuitous discovery made during its investigation in the treatment of ichthyosis1, 2. Use of 13-cis RA is associated with serious side effects including teratogenicity prompting regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration3, 4. Little preclinical data is available regarding 13-cis RA’s mechanism of acne. Studies aimed at elucidating these mechanisms are important in that they may identify novel targets for development of drugs with a greater safety margin.

Recent studies demonstrate that 13-cis RA induces apoptosis in human sebocytes both in vitro and in vivo as part of the mechanism by which it reduces sebum5. This apoptotic effect is mediated in part by the protein neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL)6. NGAL also functions in the innate immune response to Gram-negative bacteria. The gene encoding NGAL, lipocalin 2 (LCN2), is highly upregulated in patients’ skin at one week of isotretinoin therapy, but not at 8 weeks6, 7. These data suggest that NGAL is important in the early response of acne to isotretinoin. In this study, we developed methods to isolate NGAL from the skin surface and determined that NGAL is increased 2.4-fold on patients’ skin within one week of beginning isotretinoin. The increase in NGAL precedes the decrease in both sebum and P. acnes noted with isotretinoin. In addition, NGAL is increased on the skin surface of patients with acne compared to normal subjects and its expression in sebocytes is regulated by P. acnes and IL-1β. These data support the hypothesis that NGAL is an important mediator of the early response to 13-cis RA, providing a rationale for the investigation of agents that activate NGAL expression in the skin as potential therapeutic alternatives to 13-cis RA in the treatment of acne. Additional insights are provided regarding regulation of NGAL.

Materials and Methods

Human Studies

All protocols were approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and were conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects signed written informed consent before entering the study.

Two cohorts of subjects were recruited. The objective of the first cohort was to assess the levels of NGAL on the surface of the forehead. Subjects consisted of males and females (14- 40 years old) with or without acne willing to undergo a tape stripping procedure to assess the levels of NGAL on the surface of the forehead. Normal subjects without acne were recruited by advertisement. Acne subjects were identified by their dermatologist and were referred to study personnel for consent. Subjects underwent a tape stripping procedure for protein collection using D-squame standard strips (CuDerm, Dallas, TX) as follows. Three areas of the forehead skin (right, center and left) were stripped with four tapes per area (12 total). Protein was extracted from the pooled tapes according to published protocol8. Briefly, the tapes were incubated in high salt buffer (10mM Tris, pH 7.5, 140mM NaCl, 1.5M KCl, 5mM EDTA, 0.5% Tween 20) to extract protein and was concentrated in low salt buffer (10mM Tris pH 7.5). Protein was quantified and assayed for NGAL levels using ELISA.

The objective of the second cohort was to examine the temporal relationship between changes in skin surface NGAL, P. acnes, and sebum levels during the course of isotretinoin treatment. Subjects were males and females (14 to 40 years old) with severe or recalcitrant acne scheduled to receive treatment with isotretinoin. Exclusion criteria for the second cohort were use of topical antibiotics or benzoyl peroxide in the past two weeks or oral antibiotics in the past month. Subjects were identified by their dermatologist and referred to the study personnel for consent. Subjects were examined at baseline and at weeks 1, 4, and 8 following initiation of isotretinoin. At each visit, subjects underwent protein collection for NGAL levels, surface counts of P. acnes and assessment of skin surface levels of sebum. Three tape strips were obtained from each of three different areas of the forehead (9 tapes total). P. acnes was isolated from the forehead using a scrub technique 9. Skin surface levels of sebum were assessed on the forehead using a Sebumeter SM 810® (Courage & Khazaka, Cologne, Germany). Briefly, surface lipids were removed with 0.1% Trition X-100 and a reading was taken one hour later9.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human skin sections using avidin-biotin complex method and AEC development (ABC kit and AEC substrate kit for Peroxidase, Vector Laboratories, CA). Paraffin blocks were available from a previous study comparing acne lesions to normal skin taken from the backs of acne subjects10. The skin sections were subjected to deparaffinization; rehydration and antigen retrieval with TRILOGY buffer (Cell Marque, Rocklin, California). Rehydrated sections were incubated overnight with the mouse monoclonal antibody to human NGAL (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA). Negative controls were prepared with normal mouse IgG1 antibody (SCBT; Santa Cruz, CA). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin using standard procedures. For quantification of NGAL, Image Pro Plus Imaging Software version 3.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure the area of “red” (NGAL positive) compared with the total area of the sebaceous gland for each patient (n = 3). The area of NGAL staining / total area sebaceous gland, duct and adjacent follicle was calculated in uninvolved and involved follicles from acne patients. Acne follicles were also stained with H&E using standard procedures to confirm the diagnosis.

Cell Culture and Treatments

The SEB-1 human sebocyte cell line was generated by transfection of secondary sebocytes using the SV40 Large T antigen and the SEB-1 cells were cultured and maintained per published protocol11. SEB-1 cells were used as passages between 20-26 when the cells were between 50-75% confluent for all experiments.

To determine the effect of P. acnes on NGAL and IL-8 production, SEB-1 sebocytes treated for 24 hours with P. acnes sonicate in phosphate buffer at concentrations of 3μg/mL, 10μg/mL, 30μg/mL, 50μg/mL or 100μg/mL; or phosphate buffer vehicle as a negative control. SEB-1 cells were also treated with 50ng/ml of IL-1β for 24 hours to model a potential contribution of monocytes to changes in NGAL expression. Total cell lysates from adherent SEB-1 sebocytes and medium devoid of cells were collected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° C until needed. Protein concentration of each sample was determined by the BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The cell lysates and medium were used for NGAL and IL-8 ELISAs as described below. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test and considered significant if p < 0.05.

For toll-like receptor (TLR) inhibition studies, SEB-1 sebocytes were pre-treated with TLR2 or TLR4 neutralizing antibodies, mouse IgG2B (TLR2 isotype control) or goat IgG (TLR4 isotype control) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or medium alone for 1 hour before treatment with 30μg/mL of P. acnes sonicate. As controls, SEB-1 sebocytes were treated with individual TLR neutralizing antibodies alone. SEB-1 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of LPS (10-50 μg/ml) as a positive control to demonstrate that TLR4 signaling is intact. Cell lysates and medium were collected and assayed for protein content, NGAL and IL-8 ELISAs. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test and considered significant if p < 0.05.

Comparison of NGAL Expression and Secretion with P. acnes, IL-1β and 13-cis RA Treatment

To test the hypothesis that 13-cis RA increases NGAL expression to a greater extent compared to P. acnes and IL-1β, SEB-1 sebocytes were treated for 48 hours with either P. acnes (100μg/ml), IL-1β (50ng/ml), a combination of P. acnes and IL-1β or 13-cis RA (1μM). Cell lysates and medium were collected and assayed for protein content and NGAL ELISA. Experiments were repeated a minimum of three times. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t- test and considered significant if p < 0.05.

ELISA Analysis for NGAL and IL-8

Commercial colorimetric ELISAs were used to assess NGAL concentration (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in human tape strip samples, SEB-1 cell lysates and culture medium, and IL-8 concentration (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) in SEB-1 lysates and medium. For each assay, equal amounts of protein were used and samples were assayed in duplicate.

Results

A temporal relationship exists between increased NGAL levels, reduction of sebum production and decreases in P. acnes counts in patients treated with 13-cis RA

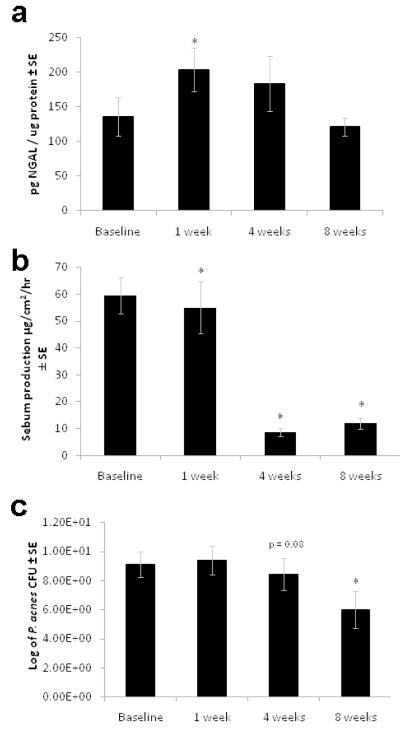

To test the hypothesis that increased NGAL contributes to decreases in sebum and P. acnes in response to isotretinoin, NGAL, sebum and P. acnes levels were assessed at various time points during treatment. A total of 15 subjects were enrolled in the second cohort of the study. NGAL secretion peaked at 1 week and leveled off at weeks 4 and 8 (Figure 1a). Sebum levels were significantly decreased at weeks 4 and 8 of treatment (Figure 1b). P. acnes cultures were taken from 9 of the 15 subjects as the others had used antimicrobials. Although P. acnes levels were highly variable among subjects, a significant reduction was noted at 8 weeks of isotretinoin treatment (p<0.05) (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Increased NGAL expression on the skin’s surface precedes the decrease in sebum secretion and P. acnes counts in subjects treated with 13-cis RA.

Subjects were recruited for the study by their dermatologist when initiating treatment with 13-cis RA. Measurements were taken at baseline, 1 week, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks into treatment.

a. NGAL levels were measured from extracts of tape strippings taken at the time points stated above. Data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank sum *p≤0.05, n=19

b. Sebum production was measured using a Sebumeter reading approximately 1h after washing with a detergent to remove skin surface lipids. Data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank sum *p≤0.05, n=19

c. Skin scrubs were cultured for P. acnes counts. Subjects were excluded from the P. acnes assessments if they had used oral antibiotics in the last month or topical antibiotics in the last 2 weeks. Data was analyzed using a Wilcoxon rank sum *p≤0.05, n=9

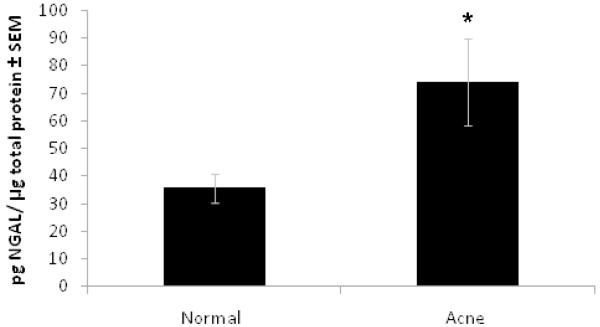

Acne patients have greater skin surface levels of NGAL compared to normal subjects

To test the hypothesis that NGAL is increased on the skin of acne subjects as compared to normal subjects, we compared skin-surface NGAL levels from the two groups. Skin-surface NGAL levels were significantly higher in acne subjects (n=15) as compared to normal subjects (n=15) (74 pg NGAL/ μg total protein vs. 36 pg NGAL/μg total protein, respectively) (p=0.028) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. NGAL is increased on the surface of the forehead of acne subjects as compared to normal subjects.

Comparison of NGAL levels from the skin surface of normal volunteers and acne subjects as assessed by ELISA assay of protein extracts from tape stripping of forehead skin. NGAL levels from acne subjects are significantly increased (p=0.028) as compared to levels from normal subjects. Data was analyzed using Student’s t-test, p<0.05, n=15 in each group.

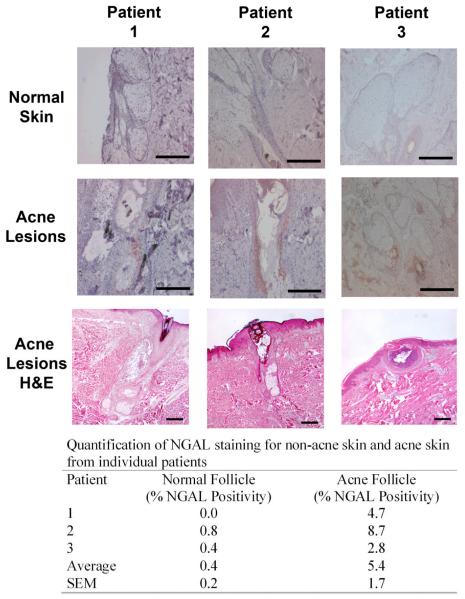

Using tissue blocks from a previous study10, acne lesions and uninvolved skin from individual subjects with acne were compared for NGAL immunoreactivity in an effort to localize the areas of increased NGAL expression. NGAL immunoreactivity was localized and quantified with positive staining recorded as the percentage of sebaceous glands, sebaceous duct and portions of the follicle adjacent to the sebaceous ducts with positive staining (Figure 3). Approximately 5.4% of the sebaceous apparatus from the acne lesions stained positively compared to 0.4% in comparable sections from uninvolved skin from the same subjects (Figure 3). The staining is predominantly localized in the follicle adjacent to the sebaceous duct where P. acnes is commonly located. Taken together, these findings suggest that NGAL is increased in acne-involved skin, both on the surface of the forehead and within the area of the sebaceous duct.

Figure 3. NGAL is increased in acne lesions compared to normal skin.

Biopsies taken from acne lesions and normal skin from the same patient were subjected to NGAL immunohistochemistry (rows 1 and 2). H&E stained sections confirm histology of the acne lesion (row 3). NGAL is predominately localized to the sebaceous duct and adjacent follicle where P. acnes commonly resides. The immunoreactivity was quantified as described in Methods. Scale bar = 250μm. n=3.

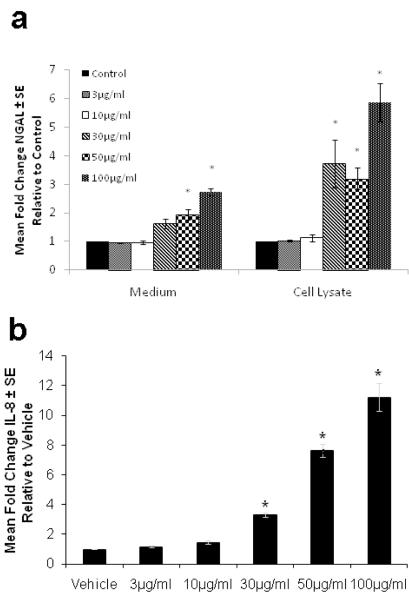

P. acnes and IL-1β induce expression and secretion of NGAL and IL-8 in SEB-1 sebocytes

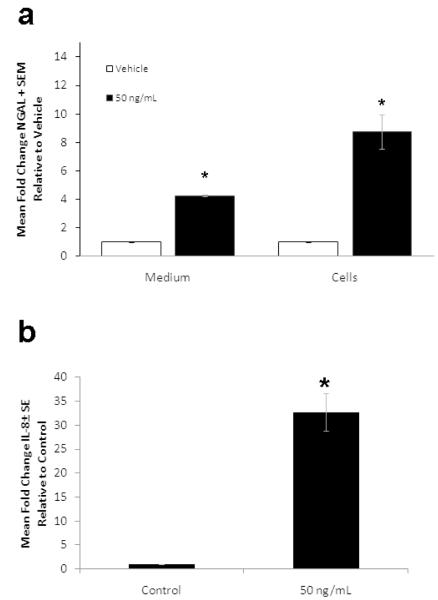

The inflammatory infiltrate in acne consists of neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes. Neutrophils secrete NGAL12. Monocytes secrete IL-1β which can regulate NGAL expression13. P. acnes promotes the release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators from monocytes and sebocytes and elicits innate responses via TLR 2 signaling14-16. We examined the effects of P. acnes and IL-1β on the expression of NGAL in SEB-1 to identify factors that may contribute to the increased levels of NGAL on the skin of acne subjects. At 24 hours, stimulation of SEB-1 sebocytes with P. acnes (100μg/ml) significantly increased both intracellular and extracellular NGAL levels compared to vehicle with fold changes of 2.7 (p = 0.004) and 5.8 (p = 0.019), respectively (Figure 4a). In the presence of IL-1β (50ng/ml), intracellular and extracellular levels of NGAL were increased 8.7-fold (p= 0.023) and 4.2-fold (p = 0.0004) compared to vehicle and, respectively (Figure 5a). Extracellular IL-8 levels were used as a positive control to demonstrate responsiveness of SEB-1 to both P. acnes and IL-1βSignificant increases in IL-8 were noted in SEB-1 treated with P. acnes and IL-1β (Figures 4b and 5b). These data indicate that SEB-1 sebocytes express and secrete NGAL and IL-8 in response to P. acnes and IL-1β.

Figure 4. P. acnes increases intracellular and secreted levels of NGAL as well as IL-8 secretion in SEB-1 sebocytes.

SEB-1 sebocytes were treated with various concentrations of P. acnes sonicate (3-100μg/mL) for 24 h. a. The cell lysate and medium were assayed separately for NGAL by ELISA. b. The culture medium was assayed for IL-8 by ELISA. All values are expressed as a fold change compared to vehicle. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test, n=3. *, p<0.05.

Figure 5. IL-1β increases intracellular and secreted levels of NGAL in SEB-1 sebocytes.

SEB-1 sebocytes were treated with 50ng/ml of IL-1β for 24 h. a. Both the cell lysate and culture medium were assayed for NGAL by ELISA. b. The culture medium was assayed for IL-8 by ELISA. All values are expressed as a fold change compared to vehicle. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test, n=3. *, p<0.05.

Induction of NGAL and IL-8 by P. acnes is mediated by TLR2 in SEB-1 sebocytes

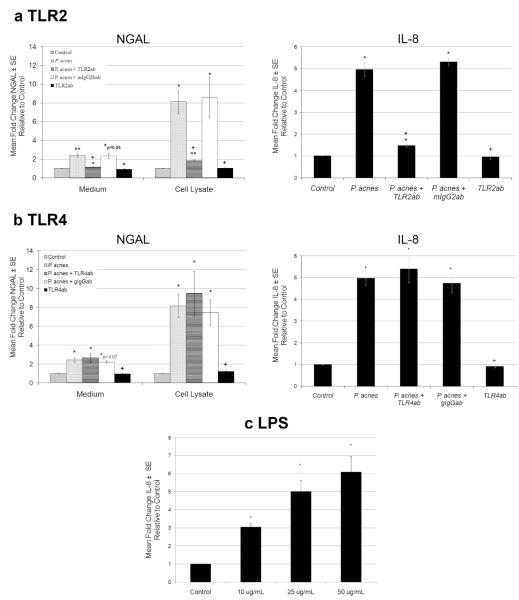

The induction of NGAL and IL-8 expression in SEB-1 cells treated with P. acnes was blocked by neutralizing antibodies to TLR2 but not to TLR4 (Figure 6a and b). In the presence of TLR2 neutralizing antibody, the induction of extracellular levels of NGAL by P. acnes decreased from a fold change of 2.42 to 1.15 (p=0.004) and intracellular levels of NGAL decreased from a fold change of 8.14 to 1.83 (p= 0.012). Pre-treatment with TLR4 neutralizing antibody did not significantly change intracellular or extracellular levels of NGAL in response to P. acnes (Figure 6b). These data indicate that NGAL expression in response to P. acnes is mediated by TLR2 signaling. As a control, P. acnes -induced IL-8 levels were also decreased in the presence of the TLR2 inhibiting antibody but not in the presence of the TLR4 antibody. Treatment of SEB-1 with LPS significantly increased IL-8 verifying that TLR4 signaling is intact in this cell line.

Figure 6. TLR2 signaling mediates P. acnes induction of NGAL in SEB-1 sebocytes.

a. SEB-1 sebocytes were pretreated with TLR2 neutralizing antibody or corresponding isotype control antibody (mIgG2b) for 1h prior to treatment with 30μg/mL P. acnes, while other samples without antibody pretreatment were treated with P. acnes, vehicle or TLR2 antibody alone for 24 h. ELISA assays for NGAL and IL-8 were performed on culture medium and cell lysates. Data was analyzed using a paired Student’s t-test n=4 *,+ p<0.05 (* is compared to vehicle and + is compared to P. acnes treatment).

b. SEB-1 cells were pretreated with TLR4 neutralizing antibody and an isotype control antibody (gIgG) for 1h prior to treatment with 30μg/mL P. acnes, while other samples with no pretreatment were treated with P. acnes, vehicle or TLR4 antibody alone for 24 h. An ELISA assay for NGAL and IL-8 was performed on culture medium and cell lysates. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test n=4 *,+ p<0.05 (* is compared to vehicle and + is compared to P. acnes treated).

c. SEB-1 sebocytes were treated with increasing concentrations of LPS (10-50μg/ml) and an ELISA assay for IL-8 was performed on culture medium to demonstrate that TLR4 signaling is intact in SEB-1 sebocytes. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test n=4 *p<0.05 (* is compared to control).

Comparison of NGAL levels in SEB-1 cells treated with P. acnes, IL-1β, and 13-cis RA

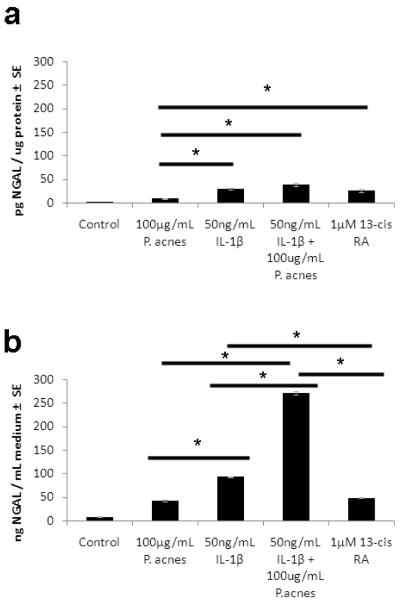

Data above indicate that NGAL is increased in patients during 13-cis RA treatment as well as in SEB-1 sebocytes following immune stimulation with P. acnes and IL-1β ( Figures 1, 4 and 5). We compared the magnitude of NGAL induction in SEB-1 following treatment with 13-cis RA, P. acnes and IL-1β. Intracellular expression of NGAL in SEB-1 was significantly increased compared to control with all treatments (Figure 7a). Within treatments, the induction of NGAL by 13-cis RA, IL-1β and by IL-1β + P. acnes was significantly greater compared to induction by P. acnes alone (p=0.043, 0.026 and 0.022, respectively). When comparing levels of NGAL secreted into the medium, the combination of P. acnes and IL-1β significantly increased NGAL secretion from SEB-1 sebocytes compared to the other treatments. NGAL secretion was 5.6-fold greater with the combination compared to 13-cis RA (p=0.0003); 2.9-fold greater than IL-1β alone (p = 0.0005) and 6.3-fold greater than P. acnes alone (p=0.0004) (Figure 7b).The secretion of NGAL with IL-1β was 1.9-fold greater than the secretion induced by 13-cis RA ( p=0.0015). There was no significant difference in secretion of NGAL in cells treated with P. acnes or 13-cis RA (p=0.9).

Figure 7. Induction of NGAL by P. acnes, IL-1β and 13-cis RA after 48 hours in SEB-1 sebocytes.

SEB-1 sebocytes were treated with 100μg/mL P. acnes, 50 ng/mL IL-1β, 100ug/mL P. acnes+ 50 ng/mL IL-1β or 1 μM 13-cis RA for 48 h. The cell lysates (a) and medium (b) were collected for an NGAL ELISA. Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test. n=3 *, p<0.05. Horizontal bars compare 2 treatments.

Discussion

Isotretinoin reduces sebum production within as early as 2 weeks17. This observation implies that the drug exerts a rapid powerful effect on inhibiting sebum production. Recent studies aimed at determining the mechanism by which this occurs indicate that apoptosis occurs within sebaceous glands of patients treated with isotretinoin in as early as one week7. Gene array expression analysis of patient skin indicates that lipocalin 2 (which encodes NGAL) is among the most highly upregulated genes at one week, but not 8 weeks of isotretinoin treatment7. Furthermore, treatment of SEB-1 sebocytes with NGAL induces apoptosis and NGAL immunoreactivity colocalizes within areas of apoptosis in patients’ sebaceous glands. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that NGAL in part mediates the early effect of isotretinoin on sebaceous glands.

In this paper, we provide additional data supporting the clinical relevance of NGAL as a mediator of the early effects of isotretinoin. This is the first study to report that NGAL protein is increased on the skin of subjects during isotretinoin treatment and this increase in NGAL precedes decreases in both sebum and P. acnes counts in patients treated with isotretinoin. These data suggests a temporal relationship wherein an increase in NGAL triggers apoptosis in sebocytes leading to reduced sebum production and P. acnes levels.

The specific mechanism by which NGAL induces apoptosis in sebocytes has yet to be determined. NGAL induces apoptosis in other cell lines by binding siderophores and changing intracellular iron levels18, 19. Mammalian siderophores (catechols and benzoic acid derivatives) have recently been identified that are hypothesized to bind NGAL and induce apoptosis via changes in intracellular iron20,21.

NGAL functions in innate immune defense against siderophore-producing Gram-negative bacteria22. Our studies are the first to report that NGAL is increased on the skin of acne subjects as compared to normal subjects and this increase is specifically located in the sebaceous ducts of acne lesions, areas adjacent to P. acnes localization in the follicle. Our in vitro studies are first to report that P. acnes induces NGAL expression via TLR2 signaling. P. acnes is capable of inducing other antimicrobial proteins such as cathelicidins, beta-defensin 2, and S100 proteins including S100A710, 23, 24. Interestingly, these proteins, as well as NGAL, are increased in psoriasis, a condition that is infrequently associated with skin infections25,26,27,28. Cathelicidins demonstrate antimicrobial activity against P. acnes. Studies in our lab failed to demonstrate an antibacterial effect of NGAL against P. acnes (data not shown). These data support the hypothesis that decreases in P. acnes during 13-cis RA treatment are secondary to the decrease in sebum, a nutrient source for this organism.

Isotretinoin is an effective treatment for Gram negative folliculitis 29-34. The mechanism of action of isotretinoin in Gram-negative folliculitis is unknown. During and after isotretinoin treatment, the levels of Gram-negative bacteria are decreased on the skin surface and in the anterior nares35. Although not addressed in this study, our data support the hypothesis that isotretinoin leads to a reduction in Gram-negative bacteria by increasing skin levels of NGAL.

Little is known regarding the regulation of NGAL expression in the skin. NGAL is induced by retinoids, cytokines including IL-1 and IL-9 as well as TLR2 and 4 signaling in different cell types7, 13, 36-39. To understand the contribution of different signaling pathways, we compared the induction of NGAL by P. acnes (TLR2 signaling), 13-cis RA and IL-1β (to model potential contribution from monocytes) in human sebocytes. We hypothesized that NGAL expression would be greater with 13-cis RA treatment compared to P. acnes treatment based on the clinical findings that skin surface levels of NGAL are significantly higher in acne patients during 13-cis RA treatment compared to baseline. Our in vitro data in sebocytes support this hypothesis and suggest that production of cytokines such as IL-1β from other cell types may augment NGAL production in the skin of acne patients. From a clinical standpoint however, administration of 13-cis RA greatly augments NGAL to levels where apoptosis is induced in sebaceous glands and Gram-negative bacteria can be inhibited on the skin surface. The current studies however do not rule out the possibility that other mediators may act in concert with NGAL to elicit these therapeutic effects.

In summary, the clinical data presented support the hypothesis that NGAL is an important mediator of the early effects of isotretinoin in acne and suggest that strategies to activate NGAL in the skin may represent therapeutic alternatives to the use of isotretinoin in acne. We demonstrate that isotretinoin increases skin surface levels of NGAL and that a temporal relationship exists between increased NGAL secretion, decreased sebum secretion and reduced P. acnes counts during isotretinoin therapy. NGAL is increased on the skin surface of acne patients and P. acnes induces NGAL expression via TLR2 signaling. The induction of NGAL by isotretinoin combined with the known efficacy of this drug in Gram negative folliculitis may provide a rationale for further study of the role of NGAL in innate immune defense in the skin.

What is Already Known?

Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment for acne but use is complicated by its teratogenicity.

Isotretinoin induces apoptosis in sebaceous glands via increasing expression of the neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin.

What this study adds?

This study demonstrates that

Isotretinoin increases NGAL on the skin surface of patients’ skin prior reducing sebum and P. acnes counts.

NGAL is increased on the skin of acne patients compared to normal subjects and

NGAL expression is regulated by P. acnes and IL-1β signaling

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NIAMS grants F31AR054723-01 to KRL, RO1AR047820 to DMT, NIH General Clinical Research Center grants M01RR010732 and C06RR016499 to The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine and the Jake Gittlen Cancer Research Foundation at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

Footnotes

All authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peck GL. Prolonged remissions of cystic acne with 13-cis-retinoic acid. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:329. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902153000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peck GL, Yoder FW. Treatment of lamellar ichthyosis and other keratinising dermatoses with an oral synthetic retinoid. Lancet. 1976;2:1172–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:837–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lammer EJ, Flannery DB, Barr M. Does isotretinoin cause limb reduction defects? Lancet. 1985;2:328. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson AM, Gilliland KL, Cong Z, et al. 13-cis Retinoic acid induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human SEB-1 sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2178–89. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson AM, Zhao W, Gilliland KL, et al. Isotretinoin temporally regulates distinct sets of genes in patient skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1038–42. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson AM, Zhao W, Gilliland KL, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin mediates 13- cis retinoic acid-induced apoptosis of human sebaceous gland cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1468–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI33869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindwall G, Hsieh EA, Misell LM, et al. Heavy water labeling of keratin as a non-invasive biomarker of skin turnover in vivo in rodents and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:841–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ. Effect of 13-cis-retinoic acid on sebum production and Propionibacterium acnes in severe nodulocystic acne. Arch Dermatol Res. 1982;272:331–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00509064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trivedi NR, Gilliland KL, Zhao W, et al. Gene array expression profiling in acne lesions reveals marked upregulation of genes involved in inflammation and matrix remodeling. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1071–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiboutot D, Jabara S, McAllister J, et al. Human skin is a steroidogenic tissue: Steroidogenic enzymes and cofactors are expressed in epidermis, normal sebocytes, and an immortalized sebocyte cell line (SEB-1) J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:905–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjeldsen L, Bainton DF, Sengelov H, et al. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel matrix protein of specific granules in human neutrophils. Blood. 1994;83:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowland JB, Sorensen OE, Sehested M, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is up-regulated in human epithelial cells by IL-1 beta, but not by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2003;171:6630–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Ochoa MT, Krutzik SR, et al. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J Immunol. 2002;169:1535–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagy I, Pivarcsi A, Kis K, et al. Propionibacterium acnes and lipopolysaccharide induce the expression of antimicrobial peptides and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in human sebocytes. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:2195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan J, Kanchanapoomi M, Liu P, et al. P. acnes induces inflammation via TLR2 and upregulates antimicrobial activity in sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:S126. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes BR, Cunliffe WJ. A prospective study of the effect of isotretinoin on the follicular reservoir and sustainable sebum excretion rate in patients with acne. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:315–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devireddy LR, Gazin C, Zhu X, et al. A cell-surface receptor for lipocalin 24p3 selectively mediates apoptosis and iron uptake. Cell. 2005;123:1293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin HH, Li WW, Lee YC, et al. Apoptosis induced by uterine 24p3 protein in endometrial carcinoma cell line. Toxicology. 2007;234:203–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devireddy LR, Hart DO, Goetz DH, et al. A mammalian siderophore synthesized by an enzyme with a bacterial homolog involved in enterobactin production. Cell. 141:1006–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao G, Clifton M, Hoette TM, et al. Iron traffics in circulation bound to a siderocalin (Ngal)-catechol complex. Nature chemical biology. 6:602–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, et al. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033–43. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakatsuji T, Kao MC, Zhang L, et al. Sebum free fatty acids enhance the innate immune defense of human sebocytes by upregulating beta-defensin-2 expression. J Invest Dermatol. 130:985–94. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DY, Yamasaki K, Rudsil J, et al. Sebocytes express functional cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides and can act to kill propionibacterium acnes. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1863–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Kye KC, Seo EY, et al. Expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation. Journal of Korean medical science. 2008;23:302–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckert RL, Broome AM, Ruse M, et al. S100 proteins in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harder J, Schroder JM. Psoriatic scales: a promising source for the isolation of human skin-derived antimicrobial proteins. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2005;77:476–86. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frohm M, Agerberth B, Ahangari G, et al. The expression of the gene coding for the antibacterial peptide LL-37 is induced in human keratinocytes during inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15258–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boni R, Nehrhoff B. Treatment of gram-negative folliculitis in patients with acne. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2003;4:273–6. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amichai B, Grunwald MH, Halevy S. Treatment of gram-negative folliculitis with isotretinoin. Harefuah. 1993;124:200–1. 47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James WD, Leyden JJ. Treatment of gram-negative folliculitis with isotretinoin: positive clinical and microbiologic response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:319–24. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DH, Cunliffe WJ, King K. Treatment of Gram-negative folliculitis with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:252–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neubert U, Plewig G, Ruhfus A. Treatment of gram-negative folliculitis with isotretinoin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:307–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00407743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plewig G, Nikolowski J, Wolff HH. Action of isotretinoin in acne rosacea and gram-negative folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:766–85. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ, Foglia AN. Qualitative and quantitative changes in cutaneous bacteria associated with systemic isotretinoin therapy for acne conglobata. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86:390–3. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12285658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caramuta S, De Cecco L, Reid JF, et al. Regulation of lipocalin-2 gene by the cancer chemopreventive retinoid 4-HPR. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1599–606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayaraman A, Roberts KA, Yoon J, et al. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a discriminatory marker of the hepatocyte-secreted protein response to IL-1beta: a proteomic analysis. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2005;91:502–15. doi: 10.1002/bit.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Draper DW, Bethea HN, He YW. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent and -independent activation of macrophages by group B streptococci. Immunology letters. 2006;102:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]