Abstract

MicroRnAs (miRnAs) are an endogenous class of regulatory small RnA (sRnA). in plants, miRnAs are processed from short non-protein-coding messenger RnAs (mRnAs) transcribed from small miRnA genes (MIR genes). Traditionally in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), the functional analysis of a gene product has relied on the identification of a corresponding T-DnA insertion knockout mutant from a large, randomly-mutagenized population. However, because of the small size of MIR genes and presence of multiple, highly conserved members in most plant miRnA families, it has been extremely laborious and time consuming to obtain a corresponding single or multiple, null mutant plant line. Our recent study published in Molecular Plant1 outlines an alternate method for the functional characterization of miRnA action in Arabidopsis, termed anti-miRnA technology. Using this approach we demonstrated that the expression of individual miRnAs or entire miRnA families, can be readily and efficiently knocked-down. Our approach is in addition to two previously reported methodologies that also allow for the targeted suppression of either individual miRnAs, or all members of a MIR gene family; these include miRnA target mimicry2,3 and transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) of MIR gene promoters.4 All three methodologies rely on endogenous gene regulatory machinery and in this article we provide an overview of these technologies and discuss their strengths and weaknesses in inhibiting the activity of their targeted miRnA(s).

Key words: MIR gene, miRNA, amiRNA, miRNA target mimicry, sRNA, siRNA, TGS, RNA silencing

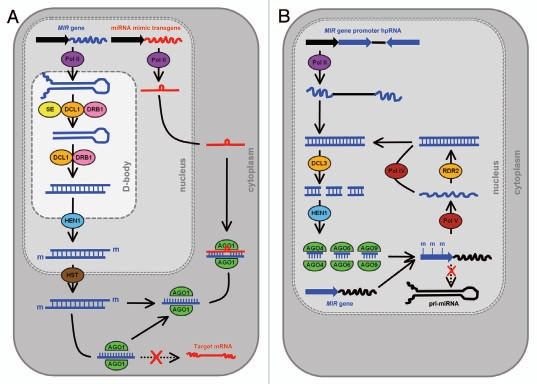

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are an endogenous class of 20–24 nucleotide (nt) small RNA (sRNA) that are key regulators of gene expression in both plants and animals.5,6 A mature miRNA is the final product of a short non-protein-coding precursor messenger RNA (mRNA) transcribed from a miRNA gene (MIR gene). This precursor transcript, the primary-miRNA (pri-miRNA), shares several features with other RNA polymerase II-transcribed mRNAs; they possess a 5′ cap and 3′ poly-A tail and are spliced.7 However, these non-protein-coding RNAs are also unique in that they contain a region of sequence that is partially self-complementary. This sequence allows the pri-miRNA to fold back onto itself to form a stem-loop structure of imperfectly double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which in plants is almost exclusively processed by the RNase III-like endonculease DICER-LIKE1 (DCL1).8,9 In specialized nuclear bodies, termed nuclear dicing or D-bodies, the initial miRNA precursor transcript processing event is catalyzed by DCL1 with the assistance of two other dsRNA-interacting proteins, SERRATE (SE) and dsRNA-BINDING DOMAIN1 (DRB1).10–13 This smaller dsRNA molecule, the precursor-miRNA (pre-miRNA) transcript, undergoes a second cleavage step to release the miRNA/miRNA* duplex from the stem-loop region. The second processing step of the Arabidopsis miRNA biogenesis pathway is also catalyzed by DCL1 in nuclear-localized D-bodies, however, DCL1 only requires the assistance of DRB1 to accurately direct this dicing event.14,15 Following methylation of the 3′ 2-nt over-hang of each duplex strand by the sRNA-specific methyltransferase HUA ENHANCER1 (HEN1),9,16 DRB1 orientates the duplex for miRNA* passenger strand degradation.17 Following nuclear export, a process which for many plant miRNAs requires the assistance of HASTY (HST),18 the miRNA guide strand is loaded to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). In Arabidopsis, miRNA-loaded RISC contains ARGONAUTE1 (AGO1) at its catalytic core and the loaded miRNA acts as a sequence specificity guide to direct cleavage of cognate mRNAs via the slicer activity of AGO1.19,20 The steps involved in the miRNA biogenesis pathway are illustrated in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic representation of the use of endogenous gene regulatory protein machinery by the miRNA target mimicry and transcriptional gene silencing of MIR gene promoter approaches. (A) Following processing in the nucleus of the miRNA precursor transcripts and exportation of the mature miRNA to the cytoplasm, the transgene-derived miRNA target mimic non-cleavable RNA sequesters the complementary sRNA, blocking the regulation of its target mRNAs. (B) expression of a hpRNA trangene targeting a MIR gene promoter results in the production of siRNAs that direct the RdDM protein machinery to methylate the promoter region, transcriptionally silencing the expression of the targeted MIR gene.

The severe developmental phenotypes displayed by plants defective in the protein machinery responsible for miRNA biogenesis, including the dcl1, drb1 and ago1 mutants, highlights the importance of miRNA-regulated gene expression for normal plant development.8,15,21 In plants, most miRNAs belong to multi-member gene families, with individual family members often expressed both spatially and temporally.22–24 In Arabidopsis, nearly 200 MIR genes have been identified and entered into the miRBase Registry (www.mirbase.org). However, to date, the function of only a small number of these have been experimentally characterized due to the lack of an effective approach to inhibit MIR gene expression. Determining the biological role(s) of a gene has classically relied on the identification of an individual of interest from a large randomly-mutagenized population. In the model dicotyledonous plant species Arabidopsis, loss-of-function T-DNA or transposon insertional mutant populations have proven to be a remarkably useful genetic tool for such an approach. Nonetheless, insertions into either small genes or loci in gene-poor regions of the genome, such as those encoding miRNA precursor transcripts, have proven to be exceedingly difficult to recover.25 Furthermore, stacking of respective mutations for individual members of multi-gene families by standard genetic crossing is both laborious and time consuming. For example, production of a null mutant plant line where the activity of all miRNA family members has been knocked out, has only been achieved for two relatively small Arabidopsis MIR gene families, namely the miR159,22 and miR164,26 families. More recently, three alternate methodologies have been developed to assist in the functional validation of miRNA action in plants, these include the (1) miRNA target mimicry, (2) transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) of MIR gene promoters, and (3) artificial miRNA-directed silencing of miRNA precursors. Here, the advantages and disadvantages of each approach will be discussed.

miRNA Target Mimicry

Franco-Zorrilla et al. were the first to report an additional layer of transcriptional regulation of miRNA action in plants, termed miRNA target mimicry. In Arabidopsis, miRNA target mimicry was originally demonstrated to be based on the co-expression of the non-protein-coding RNA Induced by phosphate starvation1 (Ips1) with the inorganic phosphate (Pi) responsive miRNA, miR399. The Ips1 mRNA contains a 23-nt partially complementary target site for miR399. The Phosphate2 (Pho2) transcript, which encodes an important negative regulator (PHO2) in the plant's response to Pi starvation, also contains a miR399 target sequence and is negatively regulated by this miRNA.27 The accumulation of miR399 has been shown to increase dramatically during the initial stages of Pi starvation leading to accelerated cleavage of Pho2.28,29 However, miR399 accumulation, and hence Pho2 expression, must promptly return to approximate wild-type levels if the plant is to avoid Pi toxicity. The authors showed that the rapid attenuation of miR399 activity, and hence stabilization of Pho2 expression, is achieved by simultaneous expression of the Pi-induced, non-protein-coding transcript Ips1.2 The partially complementary miRNA target sequence within Ips1 contains a 3-nt mismatched bulge corresponding to positions 11–13 of miR399. Most plant miRNAs cleave their mRNA targets between bases 10 and 11 of the miRNA, suggesting that Ips1 functions as a non-cleavable target mimic of miR399, leading to the sequestration of this miRNA and arrest of its activity. Based on these initial observations, the authors2 went on to demonstrate that in planta the activity of two other endogenous miRNAs, namely miR156 and miR319, could also be sequestered by constitutively overexpressing modified versions of the Ips1 transcript in which the miR399 bulged target sequence was substituted with those corresponding to the targeted miRNAs.

Detlef Weigel's research group3 subsequently applied the miRNA target mimicry approach to a large scale, modifying the endogenous miR399 23-nt bulged target site of Ips1 to express artificial miRNA target mimics for the 73 Arabidopsis MIR gene families registered in either the miRBase (www.mirbase.org) or ASRP (asrp.cgrb.oregonstate.edu) datasets at the beginning of 2007. This approach required the generation of 75 individual plant expression vectors as some miRNA families produce non-overlapping mature sRNAs, or the mismatched bulge sequence had to be modified to ensure that the vector would still produce a modified Ips1 transcript containing a non-cleavable miRNA target site. Under the control of the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35Sp), the progeny plants of 15 of the 75 miRNA target mimics used to transform Arabidopsis expressed an aerial tissue developmental phenotype. All 15 phenotype-expressing plant lines, targeting 14 MIR gene families, were transformed with mimic vectors targeting the activity of highly abundant and widely conserved miRNA families. The authors went on to show that the developmental phenotypes expressed by this series of target mimics closely replicated those previously reported for plant lines either expressing miRNA-resistant targets or harboring MIR gene T-DNA knockout insertions. Furthermore, sRNA northern blotting and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses revealed that the accumulation of the targeted miRNA is reduced and that miRNA target gene expression is conversely elevated to levels similar to those detected in plant lines deficient in the activity of the miRNA biogenesis machinery proteins DCL1, DRB1 and SE.

The main advantage offered by the miRNA target mimicry approach is that a single non-cleavable target site, and hence a single plant expression vector, can be used to reduce the accumulation of all MIR gene family members. Expressing the Ips1 non-protein-coding transcript under the control of the constitutive 35Sp further ensures that its spatial and temporal expressional pattern should be overlapping to most (if not all) family members, leading to their repression. However, this also presents a major limitation of the miRNA target mimicry technology. The high level of sequence conservation between the mature sRNAs of individual family members does not allow for the targeting of a single family member. Accordingly, the miRNA target mimicry approach would not allow for differentiation of the effect of suppressing the expression of individual MIR gene family members that are often distinct. For example, knocking out the expression of a single miR164 family member, specifically miR164c, resulted in the expression of a floral phenotype.23 Whereas, disrupting the expression of the remaining two miR164 family members (miR164a and miR164b) produced a vegetative phenotype.24,30 Such a shortcoming could be minimized by substituting the existing 35S promoter of the target mimicry vector with those of the MIR gene family members under study. This may allow for the determination of function of individual family members that are expressed spatially and/or temporally in wild-type plants. Thorough molecular and phenotypic analyses of miRNA target mimicry transformant lines is also required, as these plant lines expressed more subtle developmental phenotypes than those expressing either miRNA-resistant targets or harboring miRNA loss-of-function mutations. The miRNA target mimicry approach is outlined in Figure 1A.

Transcriptional Gene Silencing of MIR Gene Promoters

HairpinRNA (hpRNA)-directed RNA silencing readily inhibits the expression of protein-coding loci in plants31 and the association between RNA silencing and DNA methylation has long been established.32–34 It was subsequently shown that targeting a promoter region with a hpRNA vector inhibited gene expression via DNA methylation of the targeted promoter in a process termed transcriptional gene silencing (TGS).35–37 In Arabidopsis, regions of genomic DNA housing specific classes of DNA repeat are transcriptionally silenced via the endogenous protein machinery of the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway. The repeat sequences or the aberrant RNA molecules from these repeats, serve as templates for RNA transcription by either of the recently identified plant-specific DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, termed PolIV and PolV respectively.38–40 These aberrant molecules of RNA are recognized by RNADEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE2 (RDR2) for the production of dsRNA.41 The dsRNA is then processed by the nuclear-localized DCL3 to produce the specific class of siRNAs, termed repeat-associated siRNAs (rasiRNAs). Unlike the other classes of endogenous sRNA, rasiRNAs are loaded to an AGO4/AGO6/AGO9-catalyzed effector complex that directs either de novo or maintenance methylation of the cytosine residues within these sequences (Fig. 1B).42–44

In their study, Vaistij et al.4 designed two hpRNA plant expression vectors to transcriptionally silence the expression of endogenous miRNAs, miR163 and miR171a via RdDM. Each hpRNA targeted a region of sequence that incorporated the transcription start sites of MIR163 and MIR171A. The authors targeted regions upstream of the miRNA and miRNA* sequences for TGS on the rationale that the chance of suppressing MIR gene expression via RdDM would be maximized, whilst at the same time avoiding the possibility of inducing co-silencing of the targeted transcript (the pri-miRNA or pre-miRNA) via a post-transcriptional gene silencing mechanism. The accumulation of both miRNAs targeted by the two respective hpRNA vectors was determined to be significantly reduced by sRNA-specific northern blotting. Furthermore, Southern blotting using methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases and Bisulfite sequencing revealed that the transcription of both MIR genes was indeed suppressed by RdDM and that dense cytosine methylation spanned the transcription start site of both genes. In addition to detecting reduced miRNA accumulation, the authors4 went on to demonstrate that target transcript expression was also deregulated in hpRNA transformant lines (termed 163-IR and 171-IR plants respectively). In 163-IR plants, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of both predicted miR163 targets (At1g66690 and At1g66700) was upregulated compared to their relative expression in wild-type. High molecular weight northern blotting using radiolabelled transcripts spanning the miR171 target site showed that for the three targets assayed, including At2g45160, At3g60630 and At4g00150, full-length transcripts were more abundant in 171-IR plants. Although miRNA accumulation and target transcript expression was demonstrated to be down and upregulated respectively, no readily discernible phenotypic alterations were observed for the majority of plants expressing either hpRNA plant expression vector. However, the authors4 do state that the biological roles for miR163 and miR171a target genes remain to be determined and concluded that under standard growth conditions, subtle tissue or organ-specific morphological changes may have been overlooked.

The main advantage offered by this approach is that the expression of individual MIR genes can be suppressed. This is extremely advantageous for large multi-member miRNA families, allowing for the establishment of functional redundancy amongst family members and their regulated targets. The use of a miRNA target gene promoter to drive the expression of the hpRNA vector could also potentially allow for such distinctions, that is: which miRNA family member is responsible for regulating the expression of a target transcript. However, such an approach may only prove advantageous once the expressional domains of individual MIR gene family members are determined to not overlap. The authors suggest that a chimeric hpRNA vector could be developed to simultaneously knockdown the expression of multiple miRNA family members. However, Vaistij et al.4 did not demonstrate the effectiveness of such an approach in planta. Silencing different members of a gene family is possible if they share a high level of sequence homology. MIR genes are individual transcriptional units under the control of their own promoter, often displaying both spatial and temporal expression. Therefore, identifying a conserved sequence within the promoter regions of MIR gene family members is unlikely. Alternatively, a chimeric approach which stitches together target sequences from each family member will result in the generation of a highly diverse pool of siRNA species which may, in turn, dilute the efficacy of silencing of each targeted sequence. The production of a diverse siRNA population also increases the likelihood of generating a sRNA with complementarity to transcripts other than those targeted, which could induce off-target silencing and misinterpretation of the silencing response.

Artificial miRNA-Directed Anti-miRNA Technology

In plants, artificial miRNA (amiRNA) silencing vectors have been successfully used to inhibit the expression of either introduced or endogenous genes.17,45–49 The structural features of the endogenous miRNA precursor transcript on which an amiRNA plant expression vector is based are maintained while the miRNA/miRNA* duplex is replaced with amiRNA and amiRNA* sequences. Such a design ensures that the modified precursor transcripts are still recognized and processed by the protein machinery of the miRNA biogenesis pathway to produce a single specific 21-nt silencing signal. Using this technology we demonstrated that amiRNAs also readily direct RNA silencing against the precursor molecules transcribed from MIR genes.1 Targeting the mature miRNA sequence with an amiRNA suppressed the activity of all MIR gene family members due to the high level of mature miRNA sequence identity between individual family members. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the anti-miRNA approach can also direct RNA silencing against an individual MIR gene family member by designing an amiRNA to target the unconserved stem-loop region of the precursor transcript. In addition to detecting significantly reduced accumulation of both targeted miRNAs, miRNA target gene expression was determined to be deregulated, and both series of anti-miRNA plant expression lines displayed developmental phenotypes similar to those previously reported for plant lines where either MIR gene expression is knocked out or a miRNA-resistant target is expressed.

Although the anti-miRNA technology efficiently directs RNA silencing against both individual members and entire MIR gene families, we favor the use of this approach to inhibit the activity of a single family member via targeting the stem-loop region of the precursor transcript to avoid off-target silencing. The pre-miRNA stem-loop sequence between the miRNA and miRNA* varies widely both in length and sequence composition, even within MIR gene families. This allows for the design of amiRNA sRNA that will only direct cleavage of the targeted transcript. If additional MIR gene family members are to also be targeted for amiRNA-directed RNA silencing, multiple amiRNA pri-miRNA transcripts can be consecutively cloned into the same silencing vector. For example, Niu et al. demonstrated that Arabidopsis plants expressing a dimeric vector harboring two unique amiRNA pre-amiRNA stem-loop sequences that generated two specific amiRNA sRNAs against the silencing suppressor proteins, P69 and HC-Pro, were resistant to Turnip yellow mosaic virus and Turnip mosaic virus infection respectively.

Furthermore, we were able to simultaneously silence the expression of two transiently expressed reporter proteins (GFP and GUS) by co-expressing a dimeric version of the pBlueGreen amiRNA plant expression vector17 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves (unpublished data). Taken together, these results suggest that a multimeric amiRNA silencing vector would readily direct silencing against multiple MIR gene family members.

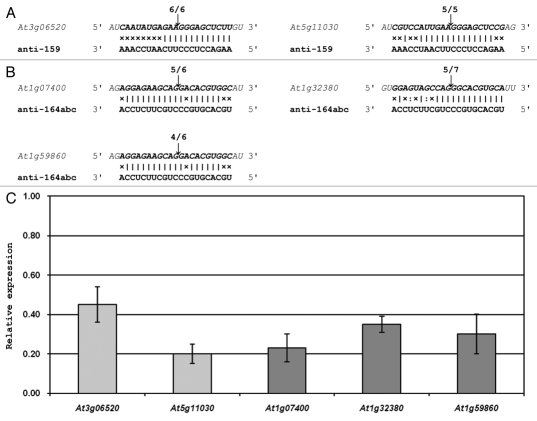

The major drawback of the anti-miRNA approach when used to interfere with the accumulation of an entire miRNA family is that there is no flexibility in choosing an amiRNA sequence that will avoid potential off-target silencing effects. The 21-nt anti-miRNA is designed to be the reverse complement of the mature miRNA consensus sequence. Most plant miRNAs belong to multi-member gene families originating from unique loci located throughout the genome. While the precursor sequences of individual MIR gene family members differ significantly in both their length and sequence composition, the mature miRNA sequences are not only tightly conserved between family members, but also between species. Therefore, there is little, if any, flexibility in the design of an amiRNA that will efficiently direct RNA silencing against all MIR gene family members. Figure 2 shows that the two sRNAs used in our study1 to inhibit the action of all miR159 and miR164 family members respectively, namely the anti-159 and anti-164abc amiRNAs, also directed cleavage of additional non-targeted transcripts. Off-target silencing could not be avoided with the expression of either of these anti-miRNAs, as only the single 21-nt shared target sequence (the mature miRNA sequence), was available for amiRNA design. This result also illustrates that a high level of caution should be applied when interpreting the phenotype expressed by a sRNA-directed (either amiRNA or hpRNA-derived siRNA) MIR gene knockdown plant line due to off-target silencing. However, the anti-miRNA plant lines generated in our study expressed developmental phenotypes similar to those previously reported for modified plant lines where either miRNA accumulation or action is altered.22,24,50

Figure 2.

Off-target silencing directed by amiRNAs designed to silence the expression of all miR159 and miR164 family members. (A) the anti-159 amiRNA is the reverse complement of the consensus sequence of the three Arabidopsis miR159 family members. This sRNA was determined to also direct mRNA cleavage-mediated silencing against two other non-targeted Arabidopsis transcripts. (B) The anti-164abc amiRNA was designed to silence the expression of all three miR164 family members. 5′ RACE analyses revealed that this exogenous sRNA also directed silencing against three additional Arabidopsis encoded genes. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis (qRT-PCR) of the expression of anti-159 (light grey columns) and anti-164abc (dark grey columns) off-target transcripts in anti-159 and anti-164abc plants respectively. The expression of all five off-targets was normalized to the Arabidopsis gene FORMATE DEHYDROGENASE (FDH; AT5G14780), and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) between three biological replicates.

Approaches to Inhibit miRNA Activity in Animals

Plant miRNAs show a very high level of sequence complementarity to the small number of closely related genes that they regulate. Furthermore, plant miRNA target sites are predominantly located within the coding region of the regulated gene. The high level of miRNA/target mRNA identity, in combination with the position of the target sequence, results in the expression of most plant miRNA target genes being regulated via RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage.19,49 As in plants, animal miRNAs have been implicated in regulating diverse biological processes including cellular differentiation, proliferation and death. Deregulation of their expression has also been linked with the onset of certain cancers and other diseases.51–53 The key difference however, is that animal miRNAs share a low level of sequence identity with their target transcripts (termed the “seed region”) and unlike plants, the partially complementary target sites of animal miRNAs are located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTRs) of the target gene(s). The low level of miRNA/target mRNA sequence similarity, in addition to target site position, has led to the prediction that animal miRNAs negatively regulate the expression of almost 30% of genome-encoded genes, via translational repression-based mechanisms.54 Bioinformatic-based predictions suggest that each animal miRNA can potentially regulate the expression of hundreds of genes, but as in plant system, confirmation of each prediction requires experimental validation. Creating genetic knockouts for each miRNA seed family member, which are encoded at multiple distant genomic loci is extremely difficult. Additionally in animals, some miRNA precursors are transcribed in clusters and the proximity of each precursor molecule within the cluster may make it extremely troublesome to obtain a clean single deletion without affecting the processing of the other cluster members. Two alternate approaches have therefore been widely adopted to validate miRNA action in animals, these include; (1) target mRNA sponges; and (2) chemically modified antisense oligonucleotides.

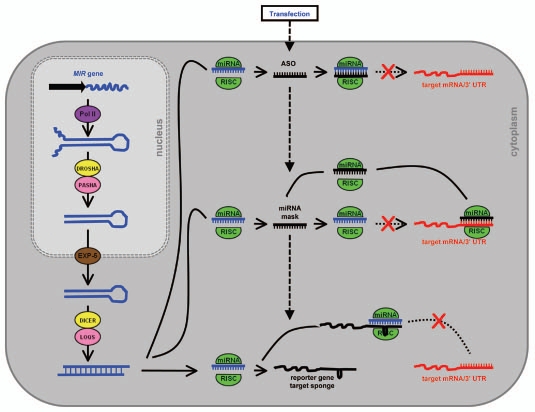

Target mRNA sponges contain miRNA target sites in either non-protein-coding transcripts or in the 3′ UTR of a reporter gene. Their expression in animal cells is driven to high levels by strong promoters such as the PolII CMV promoter or the PolIII U6 promoter.55 The use of lentiviral and retroviral vectors has enabled transient expression of the target mRNA sponge over long periods in both dividing and non-dividing cells for the continuous repression of miRNA activity in vitro.56–58 Stably introduced target mRNA sponge transgenes have also been shown to inhibit miRNA target gene regulation, but to a lower level than those expressed transiently (presumably due to the lower number of stably integrated transgene copies compared to the high number of plasmid vectors delivered via transfection).58–60 Animal miRNAs repress translation of transcripts that are complementary to the seed region of the sRNA (miRNA positions 2–8), however, more effective miRNA target sponges contain recognition sites with higher levels of identity along the entire length of the sRNA, but with a bulged mis-pairing opposite miRNA positions 9–12, preventing RNA interference-mediated cleavage (Fig. 3).55 The enhanced inhibition of miRNA function offered by such a design is presumed to result from a more stable interaction of the mRNA to the bound RISC-complexed miRNA. Analogous to the non-cleavable interaction between miRNAs and target mimics in plants, the mechanistic relatedness of these two approaches for repressing miRNA function was further demonstrated by Todesco et al.3 and Ebert et al.60 respectively. Todesco et al.3 showed that by introducing mimic-like miRNA target sites in the 3′ UTR of a protein-coding gene, the activity of the targeted miRNA was sequestered, target transcript levels remained constant and protein levels translated from the cis-linked mRNA were reduced. Furthermore, and as shown in plants harboring miRNA target mimicry vectors, Ebert et al.55 demonstrated that the levels of the targeted miRNA were reduced in mammalian cell lines expressing target mRNA sponges.61 Collectively, these observations suggest that the mechanism of miRNA repression directed by these approaches is highly similar in plants and animals, and that in both instances, non-cleavable miRNA/target mRNA interactions appears to stimulate the degradation of the sRNA via an unknown mechanism.

Figure 3.

Repressing miRNA activity in animal cells. Following the processing of the pri-miRNA and pre-miRNA transcript in the nucleus and cytoplasm, catalyzed by the RNase III-like endonucleases Drosha and Dicer respectively, the mature miRNA is unwounded from the miRNA* passenger strand and loaded to RISC. In the cytoplasm the action of the RISC-loaded miRNA on its targets is blocked and/or suppressed by the transient delivery of either a synthetic antisense oligonucleotide (ASO or miRNA mask) or mRNA target sponge transgene.

The major advantage of this approach is that a single target mRNA sponge can inhibit the expression of an entire miRNA seed family. Sponge transcripts are designed to contain multiple miRNA target sites (usually 4 to 10 sites), and when expressed at high levels this molecule can inhibit the activity of all family members sharing a common seed sequence.55 Furthermore, the addition of a reporter gene coding sequence into the same expression vector allows for fluorescence-based sorting of sponge-expressing cells. Positive selection of these cells will allow for identification of subtle changes to miRNA-regulated gene expression, when miRNA action is deregulated in only a small subset of cells, which would be otherwise masked in a large, non-selected population. Alternatively, the expression of a target mRNA sponge vector can be driven by an inducible promoter to permit tissue-specific expression. Using such an approach, Loya et al. accurately reproduce phenotypes for previously characterized loss-of-function miRNA mutants, but at lower levels of penetrance. More recently, evidence has emerged that non-protein-coding RNAs transcribed from pseudogenes may act as natural target mRNA sponges for miRNAs regulating the expression of closely related genes through the shared target sites contained in their 3′ UTRs.63 However, how such lowly abundant transcripts could effectively modulate the expression of these closely-related and highly abundant protein-coding sequences via miRNA sequestration remains to be determined.

In animals, chemically-modified antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have been widely used in vitro and in vivo to target mRNAs for RISC-mediated silencing to evaluate gene function. Owing to their similar size, miRNAs have also been effectively targeted for activity attenuation by ASOs.64–66 ASOs act as competitive inhibitors to the action of the targeted miRNA, presumably by annealing to the mature miRNA following RISC-catalyzed degradation of the miRNA* passenger strand, sequestering the guide strand to block its interaction with complementary mRNA targets (Fig. 3).67 ASOs are typically used to transiently inhibit miRNA action in transfected cells. Such an approach leads to a corresponding transient derepression of miRNA target genes for the validation of miRNA function. However, in order to be effective, ASOs require chemical modifications to not only improve their affinity for hybridization to their sRNA target, but to make the delivered molecule resistant to nuclease degradation, or to inhibit RNaseH or other protein-based responses initiated by animal cells to remove the introduced synthetic nucleic acid.68 Chemical modification is also required to delay plasma clearance and to promote ASO uptake to specific cells or tissues, in cultured cells and whole organisms respectively.69 Towards this end, the addition of conjugating agents to the ASO or co-delivery of the modified ASO with a transfection re-agent, may also be required to improve the distribution and hence effectiveness of these miRNA-inhibiting agents.70

Inhibition of miRNA action with ASOs may result in sequestration of the miRNA, degradation of the targeted miRNA, or in some cases both, making measurement of the degree of ASOdirected miRNA inhibition at the sRNA level challenging and/or misleading. Therefore, reporter genes containing in their 3′ UTR perfectly complementary recognition sequences for the targeted miRNA are often used to evaluate the effectiveness of ASO-mediated miRNA inhibition.70 However, to date, the stable integration of an ASO-generating transgene has not been reported. This limits the ASO approach to animal cell cultures requiring repeat administrations of high doses of the modified ASO and their associated transfecting agents, which may prove toxic. The major advantage offered by the ASO approach is that it can be used for the targeted repression of a single miRNA seed family member. As in plants, many animal miRNAs are members of seed families and these related sRNAs are predicted to regulate similar target mRNAs. Seed family members share a common seed sequence between positions 2 to 8 of the mature miRNA, but each family member may have one or more nucleotide differences in the remainder of its sequence. Taking advantage of these sequence differences, ASOs can be designed to specifically target a single seed family member for repression. For example, using locked nucleic acid ASOs (LNA-ASOs) complementary to miR-125b, Naguibneva et al. demonstrated that the action of the targeted miRNA was inhibited, but the activity of an unrelated miRNA, namely miR-181 remained unchanged in transfected mouse cells. Conversely, the authors went on to show that a miR-181-specific LNA-ASO repressed the activity of miR-181, while miR-125b stayed at wild-type levels. However, when four mismatch mutations were introduced into either LNA-ASO their specific inhibitory activities were abolished. The use of chemistry-matched negative controls in such assays is therefore also highly recommended to ensure that the observed phenotypic affects are a direct result of the introduced ASO.70 A modification to the established ASO approach, termed miRNA-masking, has also proven effective in disrupting miRNA-regulated gene expression in animals. As outlined for ASOs, a miRNA-masking oligonucleotide is designed to be a perfect complement to its target. However, instead of targeting the endogenous miRNA directly, the miRNA-mask is designed to interact with the miRNA binding sequences of the target mRNA. The miRNA-mask does not disrupt the activity of the miRNA itself, but binds to and protects the target mRNA from recognition by miRNA-loaded RISC (Fig. 3).72,73 MiRNA-masks therefore allow for target gene-specific validation of miRNA function.

Concluding Remarks

In Arabidopsis, the miRNA target mimicry approach efficiently and effectively knocks down the activity of all members of a MIR gene family.2,3 Todesco et al.3 elegantly demonstrated that plant lines transformed with mimicry vectors targeting highly expressed and widely conserved MIR gene families expressed developmental phenotypes similar to plant lines where either miRNA accumulation was reduced, or a miRNA-resistant target transgene was expressed. The modified, constitutively-expressed Ips1 non-protein-coding RNA is presumed to be present in the cytoplasm of most plant cells, annealing to and sequestering the activity of all members of the targeted MIR gene family. Curiously, miRNA accumulation was reportedly reduced in both the plant and animal system following the expression of either a stably-transformed miRNA target mimic vector or transiently-expressed target mRNA sponge plasmid respectively.3,55,60 The authors3,62,63 suggest that the observed reduction is due to destabilization of the bound sRNA following interaction with its non-cleavable target mRNA. However, RISC-complexed sRNAs stably bound to a non-cleavable mRNA may not be detected under the standard northern blotting denaturing conditions. We have recently demonstrated that the strong positive strand bias of siRNAs accumulating from dsRNA viral intermediates can be negated through the addition of in vitro-transcribed negative strand-specific transcripts to the extracted RNA samples.74 The addition of these spiked antisense high molecular weight transcripts resulted in the equivalent accumulation of siRNA species of both polarities, indicating that much of the negative strand-specific sRNAs are usually bound to the high-molecular-weight positive-strand viral RNAs during gel electrophoresis, preventing their detection. Thus, the observed reductions to sRNA levels reported in either miRNA target mimicry plant lines or target mRNA sponge expressing animal cells may result from failure to detect such tightly bound, complexed sRNAs.

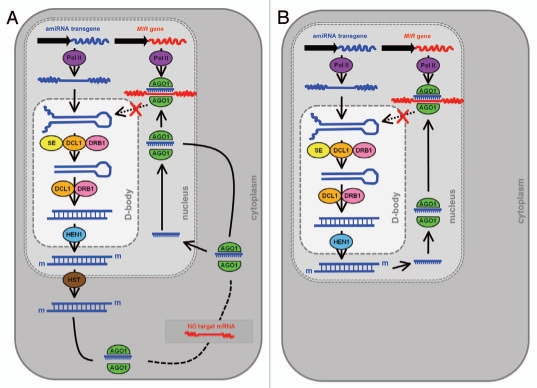

Hairpin-RNA-mediated TGS of a MIR gene promoter4 and the amiRNA-directed silencing of miRNA precursor transcripts1 are suited for the targeted repression of a single MIR gene family member. The RdDM mechanism responsible for promoter silencing has been well characterized in plants, involving several key silencing machinery components, including PolIV, PolV, DCL3, RDR2 and AGO4.39,41 Although amiRNA-mediated silencing of mRNAs has been well documented in plants, the amiRNA-directed cleavage of miRNA precursors was surprising as these transcripts are located in the nucleus and sRNA-mediated RNA cleavage was thought to occur in the cytoplasm. Is a nucleus-localized silencing pathway responsible for the repression of MIR gene activity directed by an anti-miRNA amiRNA? Figure 4 displays two alternate pathways by which the antimiRNA amiRNA could direct mRNA cleavage-based silencing of miRNA precursor transcripts in plant cells. Figure 4A depicts the characterized miRNA biogenesis pathway of Arabidopsis, that is; in the nucleus the amiRNA contained in an endogenous precursor transcript backbone is recognized and subsequently processed by DCL1 with the assistance of SE and DRB1. The amiRNA duplex strands are then methylated by HEN1 and transported to the cytoplasm by HST. In the cytoplasm, the amiRNA guide strand is unwound from the amiRNA* passenger strand and loaded onto AGO1-catalysed RISC. In the absence of a target mRNA, the amiRNA-loaded RISC, or the mature amiRNA alone, could be imported back into the nucleus to direct RNA cleavage. Mammalian studies are consistent with this scenario; sRNA-loaded RISC in the cytoplasm consists of a large AGO-based complex, whereas in the nucleus, RISC consists of little more than AGO and its loaded sRNA.75–77 Figure 4B illustrates a proposed pathway for miRNA-directed expressional regulation of nuclear-localized transcripts. Recent studies have localized the miRNA biogenesis machinery proteins DCL1, DRB1 and SE to the nucleus specialized D-bodies.10,11 In addition, HEN1 and AGO1 also show some localization to the nucleus and to D-bodies.11 In plants, the Slicer activity of AGO1 specifically co-elutes with a small protein complex,19 to suggest that miRNA-loaded RISC may consist of little more than AGO1 and its loaded sRNA. Our molecular analyses strongly suggest that miRNA precursor transcripts, namely the pri-miRNA are the target of amiRNA-directed anti-miRNA silencing technology.1 The nuclear-localization of a large complement of the protein machinery responsible for miRNA biogenesis in Arabidopsis further suggests that miRNA-directed RNA silencing is also a prevalent regulatory mechanism of gene expression in the plant cell nucleus.

Figure 4.

Proposed alternate pathways for amiRNA-mediated silencing of nuclear-localized transcripts. (A) Following processing by the endogenous miRNA biogenesis machinery proteins the amiRNA sRNA is loaded to AGO1-catalyzed RISC in the cytoplasm. The absence of a target mRNA could promote the import of the sRNA back into the nucleus, either on its own or complexed to AGO1, to direct mRNA-cleavage based silencing of cognate mRNAs, miRNA precursor transcripts. (B) Many of the miRNA biogenesis machinery proteins have been shown to be localized to the plant cell nucleus. The processed mature amiRNA sRNA could then be directly loaded to nuclear AGO1, to mediate silencing of complementary miRNA precursor transcripts.

In summary, the miRNA target mimicry approach represses the activity of all miRNA family members. Transcriptional gene silencing of a MIR gene promoter directs silencing against the individual family member targeted, whereas the anti-miRNA approach can be adopted to inhibit the expression of an individual family member or a whole MIR gene family. Although the specific mechanism of each approach remains to be fully characterized, these three alternate approaches are capable of complementing or enhancing the traditional insertion knockout mutant approach for the experimental validation of miRNA function in plants.

References

- 1.Eamens AL, Agius C, Smith NA, Waterhouse PM, Wang MB. Efficient silencing of endogenous microRNAs using artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant. 2010;4:157–170. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franco-Zorrilla JM, Valli A, Todesco M, Mateos I, Puga MI, Rubio-Somoza I, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1033–1037. doi: 10.1038/ng2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todesco M, Rubio-Somoza I, Paz-Ares J, Weigel D. A collection of target mimics for comprehensive analysis of microRNA function in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaistij FE, Elias L, George GL, Jones L. Suppression of microRNA accumulation via RNA interference in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: Are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X. MicroRNA biogenesis and function in plants. FEBS Lett. 2005;31:5923–5931. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12753–12758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403115101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park W, Li J, Song R, Messing J, Chen X. Carpel factory: a Dicer homolog and HEN1, a novel protein, act in microRNA metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1484–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01017-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang Y, Spector DL. Identification of nuclear dicing bodies containing proteins for microRNA biogenesis in living Arabidopsis plants. Curr Biol. 2007;17:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song L, Han MH, Lesicka J, Fedoroff N. Arabidopsis primary microRNA processing proteins HYL1 and DCL1 define a nuclear body distinct from the Cajal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5437–5442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L, Liu Z, Lu F, Dong A, Huang H. Serrate is a novel nuclear regulator in primary microRNA processing in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47:841–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vazquez F, Gasciolli V, Crété P, Vaucheret H. The nuclear dsRNA binding protein HYL1 is required for microRNA accumulation and plant development, but not posttranscriptional transgene silencing. Curr Biol. 2004;14:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han MH, Goud S, Song L, Fedoroff N. The Arabidopsis double-stranded RNA-binding protein HYL1 plays a role in microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1093–1098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307969100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurihara Y, Takashi Y, Watanabe Y. The interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is important for efficient and precise processing of pri-miRNA in plant microRNA biogenesis. RNA. 2006;12:206–212. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutet S, Vazquez F, Liu J, Béclin C, Fagard M, Gratias A, et al. Arabidopsis HEN1: A genetic link between endogenous miRNA controlling development and siRNA controlling transgene silencing and virus resistance. Curr Biol. 2003;13:843–848. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eamens AL, Smith NA, Curtin SJ, Wang MB, Waterhouse PM. The Arabidopsis thaliana double-stranded RNA binding protein DRB1 directs guide strand selection from microRNA duplexes. RNA. 2009;15:2219–2235. doi: 10.1261/rna.1646909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park MY, Wu G, Gonzalez-Sulser A, Vaucheret H, Poethig RS. Nuclear processing and export of microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3691–3696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405570102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumberger N, Baulcombe DC. Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1 is an RNA Slicer that selectively recruits microRNAs and short interfering RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11928–11933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505461102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tagami Y, Inaba N, Kutsuna N, Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. Specific enrichment of miRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana infected with tobacco mosaic virus. DNA Res. 2007;14:227–233. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaucheret H, Vazquez F, Crété P, Bartel DP. The action of ARGONAUTE1 in the miRNA pathway and its regulation by the miRNA pathway are crucial for plant development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1187–1197. doi: 10.1101/gad.1201404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen RS, Li J, Stahle MI, Dubroué A, Gubler F, Millar AA. Genetic analysis reveals functional redundancy and the major target genes of the Arabidopsis miR159 family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16371–16376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker CC, Sieber P, Wellmer F, Meyerowitz EM. The early extra petals1 mutant uncovers a role for microRNA miR164c in regulating petal number in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikovics K, Blein T, Peaucelle A, Ishida T, Morin H, Aida M, et al. The balance between the MIR164A and CUC2 genes controls leaf margin serration in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2929–2945. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieber P, Wellmer F, Gheyselinck J, Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM. Redundancy and specialization among plant microRNAs: Role of the MIR164 family in developmental robustness. Develop. 2007;134:105160. doi: 10.1242/dev.02817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aung K, Lin SI, Wu CC, Huang YT, Su CL, Chiou TJ. pho2, a phosphate overaccumulator, is caused by a nonsense mutation in a microRNA399 target gene. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1000–1011. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujii H, Chiou TJ, Lin SI, Aung K, Zhu JK. A miRNA involved in phosphate-starvation response in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2038–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiou TJ, Aung K, Lin SI, Wu CC, Chiang SF, Su CL. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by MicroRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:412–421. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laufs P, Peaucelle A, Morin H, Traas J. MicroRNA regulation of the CUC genes is required for boundary size control in Arabidopsis meristems. Development. 2004;131:4311–4322. doi: 10.1242/dev.01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesley SV, Helliwell CA, Smith NA, Wang MB, Rouse DT, Liu Q, et al. Construct design for efficient, effective and high-throughput gene silencing in plants. Plant J. 2001;27:581–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.English JJ, Mueller E, Baulcombe DC. Suppression of virus accumulation in transgenic plants exhibiting silencing of nuclear genes. Plant Cell. 1996;8:179–188. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones AL, Thomas CL, Maule AJ. De novo methylation and co-suppression by a cytoplasmically replicating plant RNA virus. EMBO J. 1998;17:6385–6393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones L, Hamilton AJ, Voinnet O, Thomas CL, Maule AJ, Baulcombe DC. RNA-DNA interactions and DNA interactions in post-transcriptional gene silencing. Plant Cell. 1999;11:2291–2302. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.12.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wasseneger M, Heimes S, Reidel L, Sanger HL. RNA-directed de novo methylation of genomic sequences in plants. Cell. 1994;76:567–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones L, Randcliff F, Baulcombe DC. RNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in plants can be inherited independently of the RNA trigger and requires Met1 for maintenance. Curr Biol. 2001;11:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mette MF, Aufsatz W, van der Winden J, Matzke MA, Matzke AJ. Transcriptional silencing and promoter methylation triggered by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:5194–5201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herr AJ, Molnàr A, Jones A, Baulcombe DC. Defective RNA processing enhances RNA silencing and influences flowering of Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14994–15001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606536103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onodera Y, Haag JR, Ream T, Nunes PC, Pontes O, Pikaard CS. Plant nuclear RNA polymerase IV mediates siRNA and DNA methylation-dependent heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2005;120:613–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanno T, Huettel B, Mette MF, Aufsatz W, Jaligot E, Daxinger L, et al. Atypical RNA polymerase subunits required for RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2005;37:761–765. doi: 10.1038/ng1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Searle IR, Pontes O, Melnyk CW, Smith LM, Baulcombe DC. JMJ14, a JmjC domain protein, is required for RNA silencing and cell-to-cell movement of an RNA silencing signal in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:986–991. doi: 10.1101/gad.579910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng X, Zhu J, Kapoor A, Zhu JK. Role of Arabidopsis AGO6 in siRNA accumulation, DNA methylation and transcriptional gene silencing. EMBO J. 2007;26:1691–1701. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Havecker ER, Wallbridge LM, Hardcastle TJ, Bush MS, Kelly KA, Dunn RM, et al. The Arabidopsis RNA-directed DNA methylation argonautes functionally diverge based on their expression and interaction with target loci. Plant Cell. 2010;22:321–334. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zilberman D, Cao X, Johansen LK, Xie Z, Carrington JC, Jacobsen SE. Role of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE4 in RNA-directed DNA methylation triggered by inverted repeats. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1214–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alvarez JP, Pekker I, Goldshmidt A, Blum E, Amsellem Z, Eshed Y. Endogenous and synthetic microRNAs stimulate simultaneous, efficient and localized regulation of multiple targets in diverse species. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1134–1151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niu QW, Lin SS, Reyes JL, Chen KC, Wu HW, Yeh SD, et al. Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1420–1428. doi: 10.1038/nbt1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parizotto EA, Dunoyer P, Rahm N, Himber C, Voinnet O. In vivo investigation of the transcription, processing, endonucleolytic activity and functional relevance of the spatial distribution of a plant miRNA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2237–2242. doi: 10.1101/gad.307804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qu J, Ye J, Fang R. Artificial microRNA-mediated virus resistance in plants. J Virol. 2007;81:6690–6699. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02457-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwab R, Ossowski S, Riester M, Warthmann N, Weigel D. Highly specific gene silencing by artificial microRNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1121–1133. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Millar AA, Gubler F. The Arabidopsis GAMYB-like genes, MYB33 and MYB65, are microRNA-regulated genes that redundantly facilitate anther development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:705–721. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.027920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu Y, Thomson JM, Wong HY, Hammond SM, Hogan BL. Transgenic overexpression of the microRNA miR17–92 cluster promotes proliferation and inhibits differentiation of lung epithelial progenitor cells. Dev Biol. 2007;310:442–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, et al. Transactivation of miR34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carè A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ebert MS, Sharp PA. Emerging roles for natural microRNA sponges. Curr Biol. 2010;20:858–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barbato C, Ruberti F, Pieri M, Vilardo E, Costanzo M, Ciotti MT, et al. MicroRNA-92 modulates K(+) Cl(−) co-transporter KCC2 expression in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem. 2010;113:591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang J, Zhao L, Xing L, Chen D. MicroRNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:357–364. doi: 10.1002/stem.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gentner B, Schira G, Giustacchini A, Amendola M, Brown BD, Ponzoni M, et al. Stable knockdown of microRNA in vivo by lentiviral vectors. Nat Methods. 2009;6:63–66. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scherr M, Venturini L, Battmer K, Schaller-Schoenitz M, Schaefer D, Dallmann I, et al. Lentivirus-mediated antagomir expression for specific inhibition of miRNA function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ebert MS, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: Progress and possibilities. RNA. 2010;16:2043–2050. doi: 10.1261/rna.2414110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loya CM, Lu CS, Van Vactor D, Fulga TA. Transgenic microRNA inhibition with spatiotemporal specificity in intact organisms. Nat Methods. 2009;6:897–903. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee Y, Vassilakos A, Feng N, Jin H, Wang M, Xiong K, et al. GTI-2501, an antisense agent targeting R1, the large subunit of human ribonucleotide reductase, shows potent anti-tumor activity against a variety of tumors. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:469–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zellweger T, Miyake H, Cooper S, Chi K, Conklin BS, Monia BP, et al. Antitumor activity of antisense clusterin oligonucleotides is improved in vitro and in vivo by incorporation of 2′-O-(2-methoxy)ethyl chemistry. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:934–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Davis S, Lollo B, Freier S, Esau C. Improved targeting of miRNA with antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:2294–2304. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oh SY, Ju Y, Kim S, Park H. PNA-based antisense oligonucleotides for micrornas inhibition in the absence of a transfection reagent. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:225–230. doi: 10.1089/oli.2010.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oh SY, Ju Y, Park H. A highly effective and long-lasting inhibition of miRNAs with PNA-based antisense oligonucleotides. Mol Cells. 2009;28:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Esau CC. Inhibition of microRNA with antisense oligonucleotides. Methods. 2008;44:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Naguibneva I, Ameyar-Zazoua M, Nonne N, Polesskaya A, Ait-Si-Ali S, Groisman R, et al. An LNA-based loss-of-function assay for micro-RNAs. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiao J, Yang B, Lin H, Lu Y, Luo X, Wang Z. Novel approaches for gene-specific interference via manipulating actions of microRNAs: Examination on the pacemaker channel genes HCN2 and HCN4. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:285–292. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Z, Luo X, Lu Y, Yang B. miRNAs at the heart of the matter. J Mol Med. 2008;86:771–783. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith NA, Eamens AL, Wang MB. The presence of high-molecular-weight viral RNAs interferes with the detection of viral small RNAs. RNA. 2010;16:1062–1067. doi: 10.1261/rna.2049510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guang S, Bochner AF, Pavelec DM, Burkhart KB, Harding S, Lachowiec J, et al. An Argonaute transports siRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Science. 2008;321:537–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1157647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ohrt T, Mütze J, Staroske W, Weinmann L, Höck J, Crell K, et al. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy reveal the cytoplasmic origination of loaded nuclear RISC in vivo in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6439–6449. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robb GB, Brown KM, Khurana J, Rana TM. Specific and potent RNAi in the nucleus of human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nsmb886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]