Abstract

It is remarkable that although auxin was the first growth-promoting plant hormone to be discovered, and although more researchers work on this hormone than on any other, we cannot be definitive about the pathways of auxin synthesis in plants. In 2001, there appeared to be a dramatic development in this field, with the announcement of a new gene,1 and a new intermediate, purportedly from the tryptamine pathway for converting tryptophan to the main endogenous auxin, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Recently, however, we presented evidence challenging the original and subsequent identifications of the intermediate concerned.2

Key words: auxin synthesis, YUCCA, tryptamine, N-hydroxytryptamine

The new gene was termed YUC, and the putative intermediate is N-hydroxytryptamine. It was claimed that the YUC protein, a flavin-containing monooxygenase, converts tryptamine (formed from tryptophan by decarboxylation) to N-hydroxytryptamine, which is converted via other intermediates to IAA. When the YUC gene was expressed in E. coli and the resulting protein incubated with tryptamine, a weak TLC spot resulted, which produced a mass spectrum said to match that expected from N-hydroxytryptamine.1 However, the authors did not report mass spectral data from authentic N-hydroxytryptamine, and their suggested fragmentation pattern breaks a fundamental rule of mass spectrometry (the even-electron rule).2 Nevertheless, N-hydroxytryptamine has been added to virtually all IAA synthesis schemes published since 2001.3

In 2010, LeClere et al. expressed a maize YUC gene in E. coli,4 and again claimed that the resulting protein converted tryptamine to N-hydroxytryptamine. This time, the mass spectrum was of better quality, but we have shown that it does not match that of authentic N-hydroxytryptamine, synthesised in our laboratory.2,5 We have demonstrated by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry that the protonated molecule of N-hydroxytryptamine (m/z 177) fragments to give an abundant ion at m/z 144. This was the crucial piece of evidence that the product obtained by LeClere et al. was not N-hydroxytryptamine, since their compound gave an abundant ion at m/z 160, and no ion at m/z 144.4

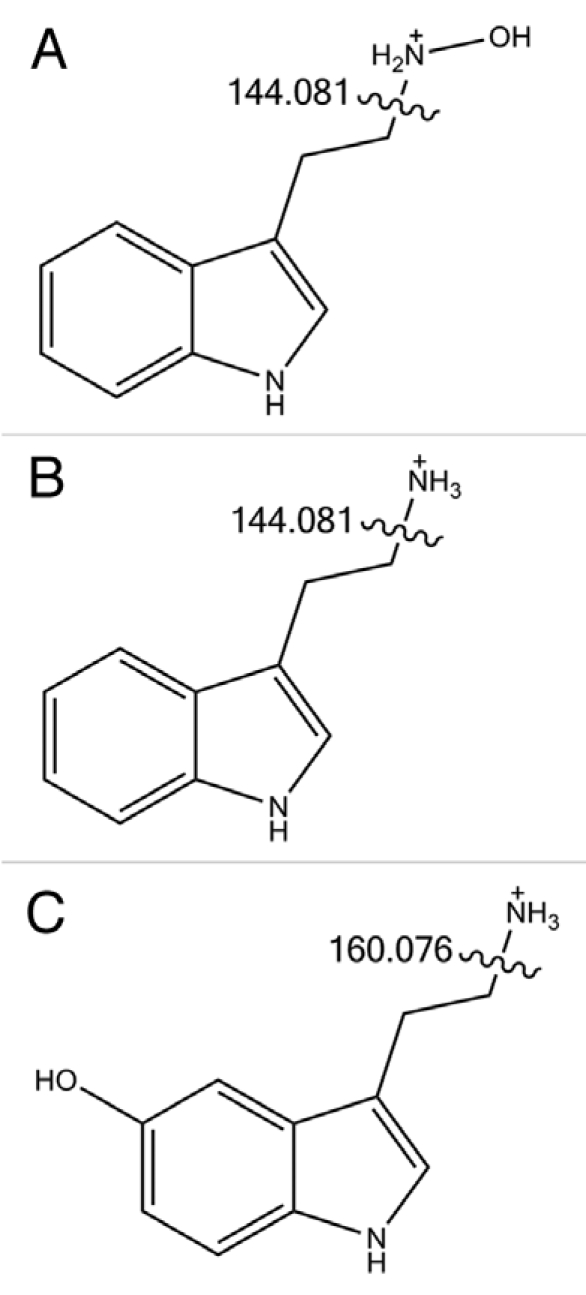

The m/z 144 ion is formed by loss of NH2OH (hydroxylamine), as shown by accurate mass determinations (Fig. 1). In other words, it is the alkyl-amine bond that is broken; this is also the case for tryptamine and serotonin. In the latter case, an m/z 160 ion results through loss of ammonia, because the hydroxyl group on the indole ring (at position 5) is retained in the fragment. The compound obtained by LeClere et al. when protonated, also had a mass of 177, consistent with a hydroxylated tryptamine, and the abundant m/z 160 ion indicates that this fragment, as in serotonin, retains the hydroxyl group.4 However, we believe that the LeClere et al. product is not serotonin, because of dissimilar behavior on thin layer chromatography. Apart from the probability that it is a hydroxylated tryptamine, the identity of the LeClere et al. product is not known.

Figure 1.

Fragmentation of (A) N-hydroxytryptamine, (B) tryptamine and (C) 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), as determined by MS/MS analysis.2 The m/z ratios of the fragments produced are indicated. The loss of neutral hydroxylamine (A) or ammonia (B and C) involves heterolytic cleavage and/or hydrogen atom rearrangement, and consequent retention of the positive charge on the remaining indole-containing fragment.14

It is interesting to contrast the previous “identifications” of N-hydroxytryptamine1,4 with the identification of gibberellins, during the period when most of the gibberellins were identified (1970–1990). There were rigorous criteria for the identification of these compounds, imposed by a triumvirate of “Gibberellin Godfathers”: Jake MacMillan, Nobatuka Takahashi and the late Bernard Phinney, and more latterly by Caporegimes such as Peter Hedden and Yuji Kamiya. Three of the present authors (James B. Reid, Noel W. Davies and John J. Ross) experienced at first hand the rigour with which these criteria were applied.

Essentially, any identification of an endogenous gibberellin was viewed with suspicion unless a synthesized form of that compound (a standard, confirmed by NMR) was available for comparison. For a firm identification, the retention time on GC should be identical between the standard and the putative compound, on the same GC instrument. Next, the electron ionization fragmentation patterns of the compound of interest and the standard should match, again on the one GC-MS system. It was not considered adequate to compare a spectrum of the compound of interest with published spectra from another laboratory. Often a spectrum from a plant extract might contain extra ions, contributed by “interfering” compounds and this was sometimes acceptable. However, the absence of ions that should be present was usually sufficient to render the identification unconvincing. Electrospray mass spectra are intrinsically much poorer in information than electron ionisation spectra since most or all of the signal is concentrated in the protonated molecule, and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is required to create diagnostic fragment ions. The MS/MS spectrum of another hydroxylated tryptamine that we have examined is dominated by a strong m/z 160 ion, and discrimination between hydroxylated tryptamines on the basis of MS alone could be problematic. N-Hydroxytryptamine is the exception in this regard, and it can be easily distinguished.

Another technique that has been used extensively in gibberellin research, and in early auxin research as well, is “feeding” labelled compounds and determining the fate of the label concerned (often deuterium or 13C). This technique contributed strongly to the identification of most of the candidate auxin pathways.6 Its power should not be underestimated, and yet in the auxin field, it was under-utilised during much of the later 1990s and the 2000s. We have used this technique to demonstrate that tryptamine is not converted to N-hydroxytryptamine in pea roots or seeds.2,5 In fact, to our knowledge, N-hydroxytryptamine has not yet been identified in any plant species.

N-Hydroxytryptamine has been the main link between the YUC genes and the tryptamine pathway, and this link is now called into question. In fact, there are some indications that YUCCAs might not be concerned with IAA synthesis at all. The floozy mutant of petunia has a strong phenotype but normal levels of IAA.7 The yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 quadruple mutant of Arabidopsis also exhibits a whole-plant phenotype but again its IAA content is not reduced compared with WT plants.8 Indeed, as yet there is not a single instance where knocking out YUC function has been shown to significantly reduce IAA content. We should note also that while overexpression of YUC genes does lead to elevated IAA content, the increase is small (up to about 2-fold1,9) compared with the increases recorded for other IAA over-producing mutants; for example, sur1 (also known as rty) and sur2, which can contain 5 to 20 times more IAA than the WT.10-12

Therefore, it is possible that YUC catalyses a reaction or reactions in another pathway leading to another compound that is required for normal plant development; hence the phenotypic consequences of loss-of-function yuc mutants. This compound might be another auxin or auxinlike compound, which might explain why elevating auxin content genetically sometimes rescues yuc phenotypes.13 The suggestion that YUC controls the synthesis of another compound was made as early as 2002,7 but has attracted little attention from auxin biologists. There seems little doubt that YUCCAs play essential roles in plant development, as evidenced by the phenotypes of knockout mutants, even though it is sometimes necessary to construct multiple mutants to observe strong phenotypes.13 Furthermore, YUC genes are found in a wide range species, and we recently extended the list to include pea.2 However, the almost universal placement of N-hydroxytryptamine in auxin synthesis schemes since 2001 is now called into question by the recently published evidence.2

References

- 1.Zhao Y, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Cashman JR, Cohen JD, Weigel D, et al. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science. 2001;291:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tivendale ND, Davies NW, Molesworth PP, Davidson SE, Smith JA, Lowe EK, et al. Reassessing the role of N-hydroxytryptamine in auxin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1957–1965. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.165803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: Regulation, action and interaction. Ann Bot. 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeClere S, Schmelz EA, Chourey PS. Sugar levels regulate tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis in developing maize kernels. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:306–318. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quittenden LJ, Davies NW, Smith JA, Molesworth PP, Tivendale ND, Ross JJ. Auxin biosynthesis in pea: Characterization of the tryptamine pathway. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1130–1138. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Normanly J, Cohen JD, Fink GR. Arabidopsis thaliana auxotrophs reveal a tryptophan-independent biosynthetic pathway for indole-3-acetic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10355–10359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tobena-Santamaria R, Bliek M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Mol JNM, Souer E, et al. FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev. 2002;16:753–763. doi: 10.1101/gad.219502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culler AH. Ph.D. Thesis 2007. St. Paul, MN USA: University of Minnesota; Analysis of the tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis pathway in maize endosperm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonhebel H, Yuan Y, Al-Amier H, Pieck M, Akor E, Ahamed A, et al. Redirection of tryptophan metabolism in tobacco by ectopic expression of an Arabidopsis indolic glucosinolate biosynthetic gene. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King JJ, Stimart DP, Fisher RH, Bleecker AB. A mutation altering auxin homeostasis and plant morphology in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:2023–2037. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delarue M, Prinsen E, Van Onckelen H, Caboche M, Bellini C. Sur2 mutations of Arabidopsis thaliana define a new locus involved in the control of auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 1998;14:603–611. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugawara S, Hishiyama S, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, et al. Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5430–5435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811226106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClean S, Robinson RC, Shaw C, Smyth WF. Characterisation and determination of indole alkaloids in frog-skin secretions by electrospray ionisation ion trap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:346–354. doi: 10.1002/rcm.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]