Abstract

Recently, we proposed a new paradigm for understanding the role of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer onset and progression. In this model, cancer cells induce oxidative stress in adjacent fibroblasts. This, in turn, results in the onset of stromal autophagy, which produces recycled nutrients to “feed” anabolic cancer cells. However, it remains unknown how autophagy in the tumor microenvironment relates to inflammation, another key driver of tumorigenesis. To address this issue, here we employed a well-characterized co-culture system in which cancer cells induce autophagy in adjacent fibroblasts via oxidative stress and NFκB-activation. We show, using this co-culture system, that the same experimental conditions that result in an autophagic microenvironment, also drive in the production of numerous inflammatory mediators (including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MIp1α, IFNγ, RANTES (CCL5) and GMCSF). Furthermore, we demonstrate that most of these inflammatory mediators are individually sufficient to directly induce the onset of autophagy in fibroblasts. To further validate the in vivo relevance of these findings, we assessed the inflammatory status of Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads, which are a model of a bonafide autophagic microenvironment. Notably, we show that Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads undergo infiltration with numerous inflammatory cell types, including lymphocytes, T-cells, macrophages and mast cells. Taken together, our results suggest that cytokine production and inflammation are key drivers of autophagy in the tumor microenvironment. These results may explain why a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a powerful predictor of poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients, as it is a marker of both (1) autophagy and (2) inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Lastly, hypoxia in fibroblasts was not sufficient to induce the full-blown inflammatory response that we observed during the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells, indicating that key reciprocal interactions between cancer cells and fibroblasts may be required.

Key words: caveolin-1, oxidative stress, cytokine production, inflammation, tumor microenvironment, autophagy, breast cancer

Introduction

We have previously shown that the co-culture of cancer cells with fibroblasts is sufficient to generate cancer-associated fibroblasts, with the upregulation of smooth muscle actin, and the activation of TGFβ signaling.1 Under these co-culture conditions, we also observed that cancer cells induce oxidative stress in the adjacent fibroblasts, resulting in the activation of two key transcription factors, namely NFκB and HIF1α.2,3 NFκB is a master regulator of inflammation, while HIF1α trancriptionally upregulates genes associated with aerobic glycolysis. Both of these factors also induce the onset of a genetic program that drives autophagy and mitophagy, the autophagic destruction of mitochondria.4,5 These results indirectly suggest that autophagy and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment should be tightly-linked biological processes. However, this association remains relatively unexplored. Importantly, both inflammation and autophagy in the tumor microenvironment have been independently associated with tumor progression and metastasis.4–15

To address these issues, here we directly examined the association between inflammation and autophagy in the microenvironment, using a variety of complementary experimental approaches. First, we show that co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells (a condition known to induce stromal autophagy) results in the induction of a “cytokine storm,” with the increased secretion of many inflammatory mediators known to be produced by cancer-associated fibroblasts. Notably, these inflammatory mediators are sufficient to induce autophagy in normal fibroblasts, using LC3-II as a marker protein, which is reminiscent of the “field effect”— in which “normal looking” areas become cancerized. Finally, we see that a known autophagic microenvironment [Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads] shows significant infiltration with inflammatory cells. Thus, inflammation and autophagy in the tumor microenvironment may work synergistically to promote tumor progression and metastasis. In support of this notion, loss of stromal Cav-1 in human breast cancer(s) is a strong prognostic biomarker of early tumor recurrence and lymph-node metastasis, as well as poor clinical outcome.16–20

Similarly, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is associated with inflammation in DCIS patients, and either a loss of stromal Cav-1 or inflammation are both individually sufficient to predict DCIS recurrence and/or progression to invasive breast cancer.17

Results

Co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells generates an activated microenvironment, rich in inflammatory mediators and growth factors.

Recently, we devised a novel co-culture system to monitor the early interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironment.1 In this co-culture system, breast cancer cells (MCF7) are co-incubated with immortalized fibroblasts for a period of up to 5 days in low-mitogen media.1 Under these conditions, we observed (using a luciferase-reporter system) that NFκB-signaling is transcriptionally activated ∼10-fold in fibroblasts within 8 hours of co-culture.2,3 These results were also confirmed using phospho-specific antibody approaches. In addition, complementary studies showed that cancer cells induce oxidative stress in fibroblasts, which is also known to drive NFκB-activation.2,3,21

Thus, one prediction of these findings is that co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells would induce the acute production of inflammatory mediators and growth factors, as NFκB-signaling transcriptionally functions as a master regulator of the inflammatory response. To address this issue, we quantitated the amounts of ∼40 known inflammatory mediators and growth factors that were released to the media. For this purpose, we prepared conditioned media from single homotypic cell cultures of fibroblasts and cancer cells (MCF7), as compared with MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures.

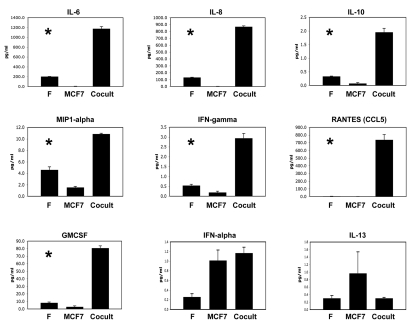

Figure 1 shows that numerous inflammatory mediators were indeed upregulated during the co-culture of fibroblasts with MCF7 cancer cells. These factors included IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MIP1α, IFNγ, RANTES and GMCSF, suggestive of a “cytokine storm.”

Figure 1.

Co-culture of fibroblasts with breast cancer cells upregulates inflammatory mediators. Breast cancer cells (MCF7) were co-incubated with immortalized fibroblasts (F) for a period of 3 days in low-mitogen media. In parallel, we prepared conditioned media from single homotypic cell cultures of fibroblasts and cancer cells (MCF7), for comparison with MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures. Note that numerous inflammatory mediators were indeed upregulated during the co-culture, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MIP1α, IFNγ, RANTES and GMCSF. An asterisk indicates statistical significance; see Table 1 for specific p-values.

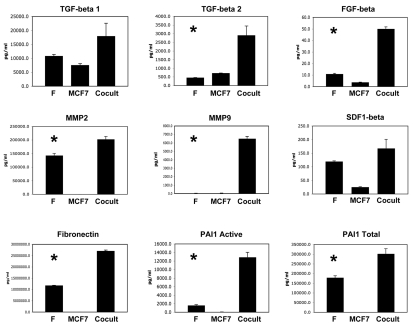

Figure 2 shows that a number of growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins were also upregulated, during the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells. The factors that were most highly increased are TGFβ2, FGFβ, MMP2, MMP9, fibronectin and activated PAI-1, consistent with an “activated” tumor microenvironment.

Figure 2.

Co-culture of fibroblasts with breast cancer cells drives the secretion of growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins. As in Figure 1, conditioned media was prepared from single homotypic cell cultures of fibroblasts (F) and cancer cells (MCF7), for comparison with MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures. Note that certain key factors were highly upregulated, including TGFβ2, FGFβ, MMP2, MMP9, fibronectin and activated PAI-1. An asterisk indicates statistical significance; see Table 1 for specific p-values.

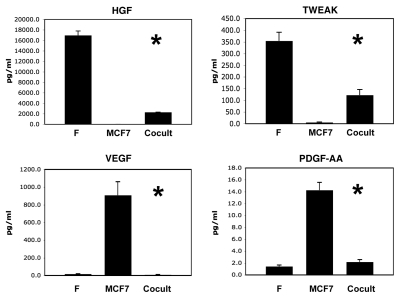

Figure 3 shows that four growth factors were also downregulated during co-culture, namely HGF, TWEAK, VEGF and PDGF-AA. Thus, certain growth factors were also downregulated or remained unchanged.

Figure 3.

Certain growth factors are also downregulated during the co-culture of fibroblasts and cancer cells. As in Figure 1, conditioned media was prepared from single homotypic cell cultures of fibroblasts (F) and cancer cells (MCF7), for comparison with MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures. Note that four growth factors were downregulated during co-culture, namely HGF, TWEAK, VEGF and PDGF-AA. An asterisk indicates statistical significance; see Table 1 for specific p-values.

A detailed summary of these results is also presented in Table 1, where all the fold-changes (co-culture vs. fibroblasts alone; and co-culture vs. MCF7 cells alone) and all the corresponding p-values are enumerated.

Table 1.

Analysis of analytes in fibroblasts alone, MCF7 cells alone and in co-culture

| Analyte(s) | Fold-change [cocult vs. fibro] | p-value | Fold-change [cocult vs. MCF7] | p-value |

| Inflammation | ||||

| IL-6 | 5.8 | 2.25E-05 | 200.2 | 1.07E-05 |

| IL-8 | 6.6 | 4.81E-07 | 601.6 | 2.08E-07 |

| IL-10 | 5.9 | 0.0003 | 25.9 | 0.0002 |

| MIP1α | 2.4 | 0.0003 | 7.1 | 1.52E-06 |

| IFNγ | 5.4 | 0.0007 | 15.5 | 0.0004 |

| RANTES | 142.1 | 0.0005 | 923.9 | 0.0004 |

| GMCSF | 9.9 | 1.98E-05 | 27.1 | 1.51E-05 |

| IFNα | 4.5 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.57; ns |

| IL-13 | 1.9 | 0.12; ns | −3.2 | 0.3; ns |

| TGF-β/Extracellular Matrix | ||||

| TGFβ1 | 1.7 | 0.2; ns | 2.4 | 0.09; ns |

| TGFβ2 | 6.5 | 0.01 | 4.1 | 0.02 |

| FGFβ | 4.6 | 2.88E-05 | 13.2 | 1.16E-05 |

| MMP-2 | 1.4 | 0.01 | 1,975.7 | 4.29E-05 |

| MMP-9 | 158.7 | 0.0002 | 170.6 | 1.14E-05 |

| SFD1β | 1.4 | 0.2; ns | 6.5 | 0.01 |

| Fibronectin | 2.3 | 1.27E-05 | 2,956.3 | 1.05E-06 |

| PAI1 Active | 8.1 | 0.0006 | 318.6 | 0.0004 |

| PAI1 Total | 1.7 | 0.01 | 1,954.5 | 0.0003 |

| Angiogenesis/EMT | ||||

| HGF | −7.4 | 6.32E-05 | 363.9 | 6.02E-07 |

| TWEAK | −2.9 | 0.006 | 23.9 | 0.008 |

| VEGF | −2.5 | 0.06 | −125.5 | 0.004 |

| PDGF-AA | 1.5 | 0.18; ns | −6.5 | 0.0009 |

ns, denotes not significant.

It is important to note that many of the cytokines and growth factors that we identified here that are upregulated and secreted in MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures, are the same cytokines and growth factors that are overexpressed by bonafide human cancer-associated fibroblasts and murine Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fibroblasts.22

Inflammatory mediators are sufficient to induce autophagy in the tumor microenvironment.

We have previously shown that MCF7 cancer cells induce oxidative stress and autophagy in adjacent fibroblasts, via the activation of certain transcription factors, such as NFκB and HIF1-α.2,3,23 We speculated that inflammatory mediators might also contribute to this process directly.

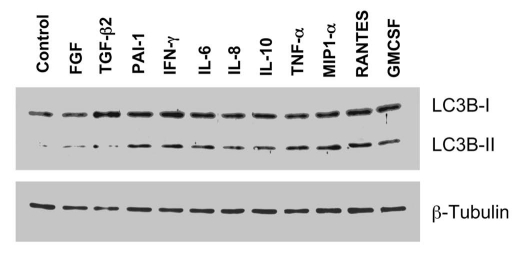

To address this issue, here we treated fibroblasts individually with the different factors that were upregulated during co-culture. Figure 4 shows that, as predicted, many of these inflammatory mediators were sufficient to induce autophagy in fibroblasts cultured alone, as detected using LC3B-II as a marker of the autophagic response. More specifically, treatment with PAI-1, IFNγ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNFα, MIP1α, RANTES or GMCSF, were all individually sufficient to induce the autophagic response in fibroblasts. Thus, cytokine production and the resulting inflammation in the tumor microenvironment can drive the onset of autophagy in cancer-associated fibroblasts.

Figure 4.

Inflammatory mediators are sufficient to induce autophagy in cultured fibroblasts. Fibroblasts were treated individually with many of the different factors that were upregulated during the MCF7-fibroblast co-culture. Note that treatment with PAI-1, IFNγ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNFα, MIP1α, RANTES or GMCSF, was sufficient to induce the autophagic response in fibroblasts. Immunoblotting with LC3 was used as a marker of the autophagic response (note the position of LC3-II); β-tubulin is also shown as a control for equal loading. Thus, inflammatory factors can drive the onset of autophagy in fibroblasts.

Autophagy in the tumor microenvironment is associated with an inflammatory response.

To test the in vivo relevance of our findings, we next studied the status of inflammation in a bonafide autophagic microenvironment. We have previously shown that the mammary fat pads of Cav-1 (−/−) null mice are a model for a lethal tumor microenvironment and constitutively undergo autophagy, which provides recycled nutrients to “feed” cancer cells.24–27 In this context, genetic ablation of Cav-1 is sufficient to drive oxidative stress, which leads to the onset of autophagy.2,3 Similarly, transient knock-down of Cav-1 in fibroblasts, using an siRNA approach, is sufficient to induce the onset of oxidative stress and autophagy, as well as NFκB activation.2,3

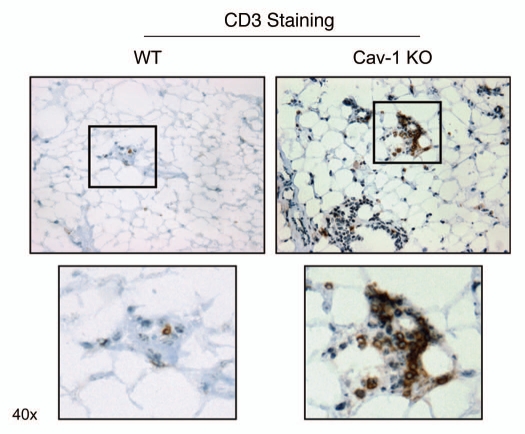

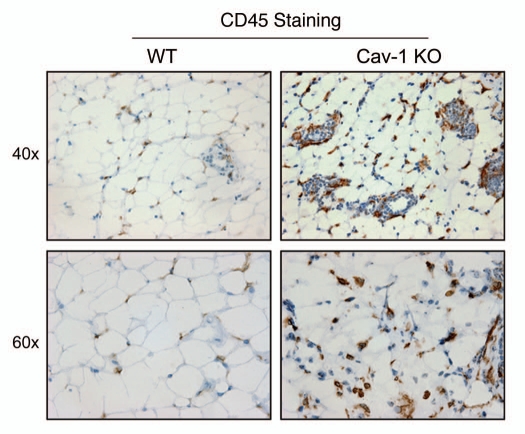

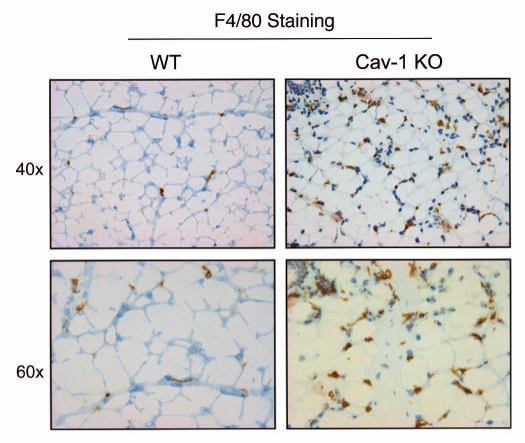

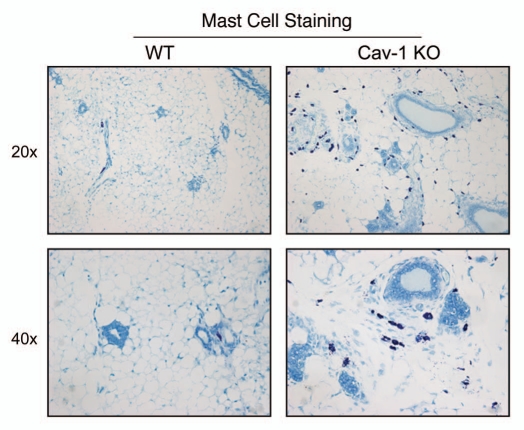

As such, we stained Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads with a variety of markers for inflammatory cells, such as CD3 (Fig. 5), CD45 (Fig. 6) and F4/80 (Fig. 7). Figures 5–7 show that the mammary fat pads of Cav-1 (−/−) null mice are rich in inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes, T-cells and macrophages. In accordance with these findings, mast cells (Fig. 8) were also quite numerous.

Figure 5.

Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads show the upregulation of CD3(+) cells. Mammary fat pads from wild-type (WT) and Cav-1 (−/−) null mice were harvested and processed for immuno-staining. Note that Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads show the upregulation of CD3(+) cells, consistent with T-cell infiltration. Boxed areas are also shown at higher magnification. Original magnification, 40x.

Figure 6.

Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads show the upregulation of CD45(+) cells. Mammary fat pads from wild-type (WT) and Cav-1 (−/−) null mice were harvested and processed for immuno-staining. Note that Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads show the upregulation of CD45(+) cells, consistent with lymphocytic infiltration. Original magnifications, 40x and 60x.

Figure 7.

Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads show the upregulation of F4/80(+) cells. Mammary fat pads from wild-type (WT) and Cav-1 (−/−) null mice were harvested and processed for immuno-staining. Note that Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads show the upregulation of F4/80(+) cells, consistent with macrophage infiltration. Original magnifications, 40x and 60x.

Figure 8.

Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pads show the upregulation of mast cells. Mammary fat pads from wild-type (WT) and Cav-1 (−/−) null mice were harvested and processed for histo-chemical staining. Note that Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads show an abundance of mast cells. Original magnifications, 20x and 40x.

Thus, it appears that loss of stromal Cav-1 in vivo is sufficient to create both an autophagic and pro-inflammatory microenvironment. This may explain why loss of stromal Cav-1 is such a powerful predictive biomarker in breast cancer patients, and is associated with tumor recurrence, metastasis and poor clinical outcome.16–20,28

Hypoxia is not sufficient to induce the complete inflammatory response observed during the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells.

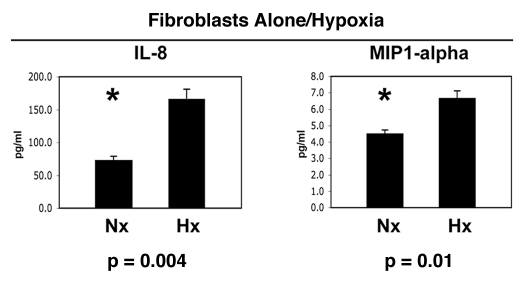

Next, we decided to test the hypothesis that hypoxia in fibroblasts could mimic the effects of co-culture with cancer cells. Thus, fibroblasts were maintained under normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (Hx) for a period of 2 days. Then, the conditioned media was collected and subjected to analysis for the secretion of ∼40 cytokines, growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins. Interestingly, Figure 9 show that only IL-8 and MIP1α were modestly induced by hypoxia in fibroblasts, in the absence of cancer cells. Thus, the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells is required for the full-blown inflammatory response, that we see in Figures 1–3.

Figure 9.

Hypoxia is not sufficient to induce the complete inflammatory response observed during the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells. Fibroblasts were maintained under normoxia (Nx) or hypoxia (Hx) for a period of 2 days. Then, the conditioned media was collected and subjected to analysis for the secretion of >40 cytokines, growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins. Note that only IL-8 and MIP1α were modestly induced by hypoxia in fibroblasts, in the absence of cancer cells. Thus, the co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells is required for the full-blown inflammatory response. An asterisk indicates statistical significance.

In addition, our results are consistent with the literature, as the secretion of both IL-8 29–32 and MIP1α33–35 is known to be induced by hypoxia in a variety of different cell types, via HIF1-dependent mechanism(s).

Discussion

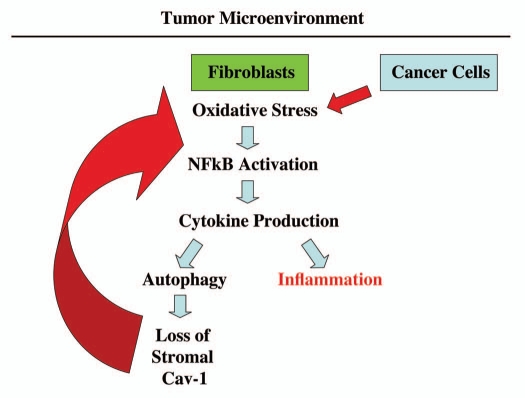

Here, we have shown that the co-culture of cancer cells with fibroblasts results in a “classic” inflammatory response, with the increased secretion of numerous inflammatory mediators, extracellular matrix proteins and growth factors. Our previous studies have mechanistically implicated oxidative stress in this process, which results in the activation of NFκB-signaling (Fig. 10), as well as the increased transcription of HIF1α target genes. Furthermore, we show that individual inflammatory mediators are sufficient to induce autophagy in cultured fibroblasts. Thus, inflammation in the tumor stroma is inextricably linked to the autophagic production of recycled nutrients that can then be re-used by anabolic cancer cells. This may explain why inflammation drives tumor progression and metastasis in pre-clinical animal models of breast cancer, and other malignancies.6–14 Furthermore, we evaluated the inflammatory state of the Cav-1 (−/−) mammary fat pad, which is a well-established model for an autophagic microenvironment. Importantly, we observed that Cav-1 (−/−) null mammary fat pads show significant infiltration with numerous types of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes, T-cells, macrophages and mast cells. Thus, it appears that inflammation drives autophagy in the tumor stroma, thereby creating an aggressive tumor microenvironment, which promotes the anabolic growth of cancer cells via the increased availability of recycled nutrients (i.e., chemical building blocks and high-energy metabolites).

Consistent with these assertions, a loss of stromal Cav-1 in breast cancer patients is a strong predictor of poor clinical outcome.16–20 For example, in triple-negative breast cancer patients, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is associated with a 5-year survival rate of <10%.18 In contrast, triple-negative breast cancer patients with high stromal Cav-1 have survival rate of >75% at even 12 years post-diagnosis.18 Thus, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a marker of a “lethal” tumor microenvironment.18

Interestingly, in DCIS patients, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is associated with inflammation in the tumor microenvironment.17 In this patient cohort, either a loss of stromal Cav-1 or inflammation were both sufficient to predict DCIS recurrence and/or progression to invasive breast cancer.17 However, a loss of stromal Cav-1 was a better predictor (as compared with inflammation) of DCIS recurrence and/or progression.17

Importantly, patients with (1) high stromal Cav-1 (a marker of decreased autophagy) and (2) increased inflammation did not show DCIS recurrence or progression.17 As loss of stromal Cav-1 is directly mediated by autophagy in the tumor stroma (lysosomal degradation), these results suggest that both inflammation and autophagy may be required to effectively promote tumor progression. Thus, future biomarker studies are warranted to explore the emerging functional relationship between loss of stromal Cav-1, autophagy and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment.

We have previously shown that MCF7 cells cultured alone have dramatically reduced levels of mitochondria, as revealed by immuno-staining with mitochondrial marker proteins, indicative of a pseudo-hypoxic state (oxidative stress and aerobic glycolysis).2,3 Consistent with this observation, here we see that MCF7 cells cultured alone secrete high levels of two angiogenic growth factors, which are known to be induced by hypoxia, namely VEGF and PDGF (Fig. 3).

Conversely, when MCF7 cells are co-cultured with fibroblasts, they show increased mitochondrial mass, due to increased mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation, which is “fueled” by lactate donated by fibroblasts.2,3 In accordance, with this shift away from pseudo-hypoxia, the MCF7 cells in co-culture show dramatic reductions in VEGF and PDGF secretion (Fig. 3). Thus, the metabolic changes we observe in MCF7 cells (alone versus co-culture) can have profound effects on the profile of what growth factors they are secreting.

IL-6 is a known growth factor and mediator of inflammation that is commonly secreted by cancer associated fibroblasts,36 and promotes the growth of cancer stem cells.37 Interestingly, IL-6 treatment of cells is sufficient to induce aerobic glycolysis.38 Conversely, IL-6 can be induced by ROS species and autophagy.39 These observations are consistent with the idea that autophagy, mitophagy and aerobic glycolysis are both a cause and a consequence of inflammation. Thus, cytokine production and inflammation provide a feed-forward mechanism for autophagy, mitophagy and aerobic glycolysis in the tumor stromal microenvironment. Similarly, it has been observed that mitochondrial-derived ROS species drive inflammatory cytokine production,40,41 consistent with our current hypothesis (Fig. 10).

Experimental Procedures

Materials.

Antibodies were obtained as follows: LC3B (Cat # ab58610, Abcam), β-tubulin (Sigma), CD3 (Cat # 555273, BD Biosciences), CD45 (Cat # 550539, BD Biosciences), F4/80 (Cat # RDI-T2008X, Fitzgerald Industries Intl.). Recombinant cytokines were obtained from PeproTech.

Cell culture.

Cell culture experiments were carried out as previously described with minor modifications.1 Human foreskin fibroblasts immortalized with human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT-BJ1) were purchased originally from Clontech, Inc. The breast cancer MCF7 cell line was from ATCC. All cells were maintained in complete media consisting of DMEM, with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and Penicillin 100 units/mL-Streptomycin 100 µg/mL (all from Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

MCF7-fibroblast co-cultures.

For co-culture experiments, fibroblasts and MCF7 cells were co-plated in complete media at a 5:1 fibroblast-to-epithelial cell ratio.1 Fibroblasts were plated first and MCF7 cells were plated within 2 hours of fibroblast plating. The total number of cells for a 10 cm dish was 1.5 × 106 cells. As controls, homotypic cultures of fibroblasts and MCF7 cells were plated in parallel, using the same number of a given cell population as the corresponding co-cultures. The day after plating, the media was changed to DMEM with 10% NuSerum I (a low protein alternative to FBS; BD Biosciences) and Pen-Strep. After three days of culture, the media was collected, spun down to remove cellular debris and subjected to cytokine analysis.

ELISA assays on secreted proteins.

Levels of ∼40 different growth factors, cytokines and chemokines were measured in tissue culture supernatants using SearchLight Protein Arrays (Aushon Biosystem, Billerica, MA).22 The SearchLight Protein Array is a quantitative multiplexed sandwich ELISA containing different capture-antibodies spotted on the bottom of a 96-well microplate. Each antibody detects specific protein present in the standards and samples. The bound proteins are then detected with a biotinylated detection antibody, followed by the addition of streptavidin-HRP and lastly, SuperSignal Chemiluminescent substrate. The luminescent signal is measured by imaging the plate using the SearchLight Imaging System, which is a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. The data is then analyzed using ArrayVision customized software. The amount of luminescent signal produced is proportional to the amount of each protein present in the original standard or sample. Concentrations are extrapolated from standard curves. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using the Student's t-test, assuming a normal distribution. A p-value lower that 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cytokine stimulation.

Fibroblasts (5.4 × 105 cells/dish) were plated in 6 cm dishes. After 12 hours, fibroblasts were incubated with the indicated cytokine for 48 hours. Then, cells were harvested and subjected to western blot analysis, using LC3B antibodies. The following concentrations of “cytokines/growth factors” were used: FGFβ (150 pg/mL), TGFβ2 (10 ng/mL), PAI-1 (0.44 µg/mL), IFNγ (10 pg/mL), IL-6 (3 ng/mL), IL-8 (2.5 ng/mL), IL-10 (6 pg/mL), TNFα (50 pg/mL), MIP1α (30 pg/mL), RANTES (2 ng/mL) and GMCSF (250 pg/mL), each in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 10% NuSerum I. The concentration utilized for each factor was ∼3-fold higher than the levels observed during the co-culture of fibroblasts with MCF7 cells.

Western blotting.

Cells were harvested in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Hcl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 60 mM octyl-glucoside), containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). After rotation for 40 min at 4°C, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 g at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA reagent (Pierce). Proteins (30 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membrane (Fisher Scientific). After blocking for 30 min in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) with 5% nonfat dry milk, membranes were incubated with the primary antibody for 1 hour, washed and incubated for 30 minutes with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The membranes were washed and incubated with an enhanced chemi-luminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Animal studies.

Animals [WT and Cav-1 (−/−) null mice in the FVB/N genetic background42,43] were housed and maintained in a pathogen-free environment/barrier facility at the Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University under National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Mice were kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to chow and water. All animal protocols used for this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Four-month old mice were sacrificed and the mammary glands were harvested and either fixed with 10% formalin or flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen cooled isopentane.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5–6 micron frozen sections, with a 3-step biotin-streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase method. Sections were fixed with acetone at −20°C for 5 min, air-dried and blocked with 10% rabbit serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies were then incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, samples were incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) followed by streptavidin-HRP (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Immunoreactivity was revealed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine.

Mast cell staining.

Mammary gland paraffin sections were de-paraffinzied and re-hydrated to H2O. Sections were stained for 1 minute with 1% Toluidine Blue O (Sigma) in isopropanol, washed in water to remove excess color and dipped in 95% ethanol to enhance purple mast cell staining. Sections were then air-dried, placed in xylene for 5 min and mounted with Permount.

Hypoxia conditions.

Fibroblasts cultured alone were incubated in hypoxia (0.5% O2) or normoxia (21% O2) for 2 days. Briefly, hTERT-BJ1 fibroblasts (5.4 × 105 cells/dish) were first seeded in 6 cm tissue culture plates with complete media consisting of DMEM, with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and Penicillin 100 units/mL-Streptomycin 100 µg/mL. One day after seeding, the media was changed to in DMEM with 10% NuSerum I (a low protein alternative to FBS; BD Biosciences) and Pen-Strep. Then, hypoxia experiments were carried out for 2 days, using a standard hypoxia chamber with 0.5% O2.

Figure 10.

An emerging functional relationship between cytokine production, autophagy and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Co-culture of fibroblasts with cancer cells drives the onset of oxidative stress and NFκB-activation in cancer-associated fibroblasts.2,3 Here, we show that one of the consequences of this reciprocal interaction, between fibroblasts and cancer cells, is elevated cytokine production, which may drive both autophagy and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Autophagy in cancer-associated fibroblasts destroys Cav-1 (via lysosomal degradation),1 further driving oxidative stress and NFκB activation (marked by the large red arrow). Importantly, transient knock-down of Cav-1 in fibroblasts, using an siRNA approach, is sufficient to induce the onset of oxidative stress and autophagy, as well as NFκB activation.2,3

Acknowledgments

F.S. and her laboratory were supported by grants from the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust, the Breast Cancer Alliance (BCA) and a Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (ACS). M.P.L. was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (R01-CA-080250; R01-CA-098779; R01-CA-120876; R01-AR-055660) and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. A.K.W. was supported by a Young Investigator Award from the Breast Cancer Alliance, Inc., and a Susan G. Komen Career Catalyst Grant. R.G.P. was supported by grants from the NIH/NCI (R01-CA-70896, R01-CA-75503, R01-CA-86072 and R01-CA-107382) and the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust. The Kimmel Cancer Center was supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Core grant P30-CA-56036 (to R.G.P.). Funds were also contributed by the Margaret Q. Landenberger Research Foundation (to M.P.L.). This project is funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health (to M.P.L. and F.S.). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. This work was also supported, in part, by a Centre grant in Manchester from Breakthrough Breast Cancer in the UK (to A.H.) and an Advanced ERC Grant from the European Research Council.

References

- 1.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Daumer KM, Milliman JN, Chiavarina B, et al. Tumor cells induce the cancer associated fibroblast phenotype via caveolin-1 degradation: Implications for breast cancer and DCIS therapy with autophagy inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2423–2433. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Trimmer C, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Zhou J, et al. Autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts promotes tumor cell survival: Role of hypoxia, HIF1 induction and NFκB activation in the tumor stromal microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3515–3533. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM, Rivadeneira DB, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Wang C, et al. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3256–3276. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Howell A, Pestell RG, Tanowitz HB, Sotgia F, et al. Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in cancer: Integrating autophagy and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.023. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pavlides S, Chiavarina B, Bonuccelli G, Casey T, et al. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer or “battery-operated tumor growth”: A simple solution to the autophagy paradox. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4297–4306. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Macrophages: Modulators of breast cancer progression. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;256:158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian B, Deng Y, Im JH, Muschel RJ, Zou Y, Li J, et al. A distinct macrophage population mediates metastatic breast cancer cell extravasation, establishment and growth. PLoS One. 2009;4:6562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojalvo LS, King W, Cox D, Pollard JW. High-density gene expression analysis of tumor-associated macrophages from mouse mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1048–1064. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard JW. Macrophages define the invasive microenvironment in breast cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:623–630. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Tumor-associated macrophages press the angiogenic switch in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5064–5066. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin EY, Li JF, Gnatovskiy L, Deng Y, Zhu L, Grzesik DA, et al. Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11238–11246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyckoff J, Wang W, Lin EY, Wang Y, Pixley F, Stanley ER, et al. A paracrine loop between tumor cells and macrophages is required for tumor cell migration in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7022–7029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin EY, Gouon-Evans V, Nguyen AV, Pollard JW. The macrophage growth factor CSF-1 in mammary gland development and tumor progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7:147–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1020399802795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisanti MP, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Tsirigos A, et al. Understanding the “lethal” drivers of tumor-stroma co-evolution: Emerging role(s) for hypoxia, oxidative stress and autophagy/mitophagy in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:537–542. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.6.13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witkiewicz AK, Casimiro MC, Dasgupta A, Mercier I, Wang C, Bonuccelli G, et al. Towards a new “stromal-based” classification system for human breast cancer prognosis and therapy. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1654–1658. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Nguyen KH, Liu C, Kovatich AJ, Schwartz GF, et al. Stromal caveolin-1 levels predict early DCIS progression to invasive breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1167–1175. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.11.8874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Sammons S, Er O, Potoczek MB, Guiles F, et al. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts poor clinical outcome in triple negative and basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:135–143. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.2.11983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witkiewicz AK, Dasgupta A, Sotgia F, Mercier I, Pestell RG, Sabel M, et al. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2023–2034. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan EK, Ciocca D, Pouliot N, Natoli A, Restall C, Henderson M, et al. Stromal cell expression of caveolin-1 predicts outcome in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2035–2043. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimmer C, Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Balliet RM, Eaton G, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Caveolin-1 and mitochondrial SOD2 (MnSOD) function as tumor suppressors in the stromal microenvironment: A new genetically tractable model for human cancer associated fibroblasts. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:383–394. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.4.14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sotgia F, Del Galdo F, Casimiro MC, Bonuccelli G, Mercier I, Whitaker-Menezes D, et al. Caveolin-1−/− null mammary stromal fibroblasts share characteristics with human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:746–761. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiavarina B, Whitaker-Menezes D, Migneco G, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Howell A, et al. HIF1alpha Functions as a tumor promoter in cancer associated fibroblasts and as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer cells: Autophagy drives compartment-specific oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3534–3551. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Migneco G, Whitaker-Menezes D, Chiavarina B, Flomenberg N, et al. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer: Role of oxidative stress and ketone production in fueling tumor cell metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3485–3505. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Vera I, Flomenberg N, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, et al. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 leads to oxidative stress, mimics hypoxia and drives inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, conferring the “reverse Warburg effect”: A transcriptional informatics analysis with validation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2201–2219. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.11.11848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Vera I, Flomenberg N, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, et al. Transcriptional evidence for the “reverse Warburg effect” in human breast cancer tumor stroma and metastasis: similarities with oxidative stress, inflammation, Alzheimer's disease and “neuronglia metabolic coupling”. Aging. 2010;2:185–199. doi: 10.18632/aging.100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, et al. The reverse Warburg effect: Aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3984–4001. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Vizio D, Morello M, Sotgia F, Pestell RG, Freeman MR, Lisanti MP. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 is associated with advanced prostate cancer, metastatic disease and epithelial Akt activation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2420–2424. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cane G, Ginouves A, Marchetti S, Busca R, Pouyssegur J, Berra E, et al. HIF-1alpha mediates the induction of IL-8 and VEGF expression on infection with Afa/Dr diffusely adhering E. coli and promotes EMT-like behaviour. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:640–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn JK, Koh EM, Cha HS, Lee YS, Kim J, Bae EK, et al. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in hypoxia-induced expressions of IL-8, MMP-1 and MMP-3 in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:834–839. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Natarajan R, Fisher BJ, Fowler AA., 3rd Hypoxia inducible factor-1 modulates hemin-induced IL-8 secretion in microvascular endothelium. Microvasc Res. 2007;73:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen RS, Gu Y, Zhang Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y. Hypoxia promotes interleukin-6 and -8 but reduces interleukin-10 production by placental trophoblast cells from preeclamptic pregnancies. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:428–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang T, Li P. [Expression and significance of mRNA for MIP-1alpha in cerebral tissue of newborn rat with hypoxic-ischemic brain damage] Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2005;36:240–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowell RM, Xu H, Galasso JM, Silverstein FS. Hypoxic-ischemic injury induces macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha expression in immature rat brain. Stroke. 2002;33:795–801. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang JY, Shum AY, Chao CC, Kuo JS. Production of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 following hypoxia/reoxygenation in glial cells. Glia. 2000;32:155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu S, Ginestier C, Ou SJ, Clouthier SG, Patel SH, Monville F, et al. Breast cancer stem cells are regulated by mesenchymal stem cells through cytokine networks. Cancer Res. 2011;71:614–624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1397–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ando M, Uehara I, Kogure K, Asano Y, Nakajima W, Abe Y, et al. Interleukin 6 enhances glycolysis through expression of the glycolytic enzymes hexokinase 2 and 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3. J Nippon Med Sch. 2010;77:97–105. doi: 10.1272/jnms.77.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoon S, Woo SU, Kang JH, Kim K, Kwon MH, Park S, et al. STAT3 transcriptional factor activated by reactive oxygen species induces IL6 in starvation-induced autophagy of cancer cells. Autophagy. 2010;6:1125–1138. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naik E, Dixit VM. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species drive proinflammatory cytokine production. J Exp Med. 2011;208:417–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bulua AC, Simon A, Maddipati R, Pelletier M, Park H, Kim KY, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote production of proinflammatory cytokines and are elevated in TNFR1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) J Exp Med. 2011;208:519–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams TM, Medina F, Badano I, Hazan RB, Hutchinson J, Muller WJ, et al. Caveolin-1 gene disruption promotes mammary tumorigenesis and dramatically enhances lung metastasis in vivo: Role of Cav-1 in cell invasiveness and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2/9) secretion. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51630–51646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams TM, Sotgia F, Lee H, Hassan G, Di Vizio D, Bonuccelli G, et al. Stromal and epithelial caveolin-1 both confer a protective effect against mammary hyperplasia and tumorigenesis: Caveolin-1 antagonizes cyclin d1 function in mammary epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1784–1801. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]