Abstract

The electronic structure of a genuine paramagnetic des-oxo Mo(V) catalytic intermediate in the reaction of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (DMSOR) with (CH3)3NO has been probed by EPR, electronic absorption and MCD spectroscopies. EPR spectroscopy reveals rhombic g- and A-tensors that indicate a low-symmetry geometry for this intermediate and a singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) that is dominantly metal centered. The excited state spectroscopic data were interpreted in the context of electronic structure calculations, and this has resulted in a full assignment of the observed magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) and electronic absorption bands, a detailed understanding of the metal-ligand bonding scheme, and an evaluation of the Mo(V) coordination geometry and Mo(V)-Sdithiolene covalency as it pertains to the stability of the intermediate and electron transfer regeneration. Finally, the relationship between des-oxo Mo(V) and des-oxo Mo(IV) geometric and electronic structures is discussed relative to the reaction coordinate in members of the DMSOR enzyme family.

Keywords: DMSO Reductase, ditholene, molybdenum, magnetic circular dichroism, electronic structure, electron paramagnetic resonance, molecular orbital, redox orbital, reaction coordinate

INTRODUCTION

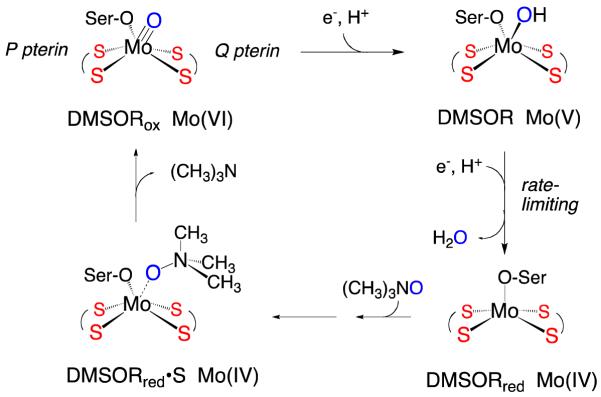

Pyranopterin Mo enzymes catalyze a variety of oxidation-reduction reactions using organic and inorganic substrates, and play important roles in the global cycles of nitrogen and carbon, as well as the detoxification of species such as sulfite, arsenite, and chlorate.1,2 The dimethylsulfoxide reductases (DMSORs) 3-5 are bacterial enzymes that catalyze an oxygen atom transfer (OAT) from the substrate to a reduced des-oxo Mo(IV) active site, generating a monooxo Mo(VI) center (Figure 1).3 Two sequential electron-proton transfer steps then regenerate the reduced, catalytically competent active Mo(IV) state, releasing the transferred oxygen as water. Resonance Raman spectroscopy,6-10 X-ray absorption spectroscopy,11-13 and a high resolution (1.3 Å) crystal structure14 indicate a distorted trigonal prismatic mono-oxo [(dt)2MoVIO(OSer)] structure for the oxidized active site, where dt represents the ene-1,2-dithiolate (dithiolene) side chain of the pyranopterin cofactor that coordinates to the metal in a bidentate manner and OSer is a serinate oxygen donor. X-ray crystallographic and EXAFS studies of the reduced form of DMSOR are consistent with a des-oxo [(dt)2MoIV(OSer)] active site with a distorted square-pyramidal coordination geometry (Figure 1).15-17 The two equivalents of the pyranopterin are designated P and Q on the basis of their disposition in the protein structure, and the presence of two pyranopterins is a structural characteristic common to all DMSOR family enzymes. The precise function of the pyranopterin dithiolenes has not yet been determined, but evidence suggests they play key roles in electron transfer, modulation of the center’s reduction potential, and maintenance of specific coordination geometries along the reaction coordinate.18-22 Additionally, the nature of the protein-derived serinate ligand may further modify the energy of the redox-active Mo orbital and fine tune the effective nuclear charge of the metal center in order to poise the reduction potentials of the active site at values which are appropriate for catalysis.23,24

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism for DMSOR with (CH3)3NO as oxidizing substrate. The Mo(V) species depicted is that responsible for the “high-g split” EPR signal observed under turnover conditions. Ser-O is the serinate oxygen donor provided by the protein.

Structural and functional synthetic models of the DMSOR active site have proven invaluable to our understanding of electronic and geometric structure contributions to the mechanism of the enzyme.25 Complexes of the general formula [NEt4][MoIV(QAd)(S2C2Me2)2] (Ad = 2-adamantyl; Q = O, S, or Se) have been synthesized as symmetrized analogues of the reduced DMSOR active site,23,26-28 and these have been studied in detail by electronic absorption and resonance Raman spectroscopies, DFT bonding calculations, and most recently by S K-edge x-ray absorption spectroscopy. 15,23 A number of theoretical studies have probed the reaction coordinate of the DMSOR oxygen atom transfer half-reaction in order to understand the binding of DMSO to a geometry-optimized five-coordinate square-pyramidal [MoIV(OCH3)(dithiolene)2]1− computational model, and the eventual release of the DMS product following oxidation of the Mo center to form six-coordinate [MoVI(O)(OCH3)(dithiolene)2].15,29-31 In general, the calculated reaction profiles can be understood in terms of an associative mechanism with two transitions states, the second being rate-limiting, and a single intermediate. Webster et al.31 concluded, on the basis of density functional calculations, that the observed distortion of the dithiolene ligand at the transition state, which is similar to the distortion observed in the X-ray crystal structure of the enzyme, represents an example of the entatic principle. Thus, the geometry enforced by the protein primarily acts to maintain an active site geometry similar to that of the transition state for oxygen atom transfer, and to destabilize the oxidized molybdenum center.23,31 Subsequent studies have been in general agreement with these conclusions.15,23 In summary, the rate-determining step in the computational studies was determined to be atom-transfer/product-release and not substrate binding when using five-coordinate, square pyramidal [Mo(OCH3)(dithiolene)2]1− as the computational model and DMSO as substrate.

Here we have performed EPR, electronic absorption, and MCD spectroscopic studies on a genuine paramagnetic des-oxo Mo(V) catalytic intermediate (IMo(V)) for DMSOR that builds up to ~100% of the total enzyme concentration during turnover with the alternate substrate (CH3)3NO (trimethylamine-N-oxide). The appearance of IMo(V) occurs in the reductive (i.e. electron transfer) half reaction of the DMSOR catalytic cycle. This is important mechanistically, since the thermodynamically stable Mo(VI)≡O bond is broken in this half reaction. The spectroscopic data have been interpreted in the context of electronic structure calculations which have allowed for a detailed understanding of the singly-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) of the signal-giving species, an evaluation of the Mo(V) coordination geometry and Mo(V)-Sdithiolene covalency as it pertains to electron transfer regeneration, and full electronic absorption and MCD band assignments. This study provides evidence for an energetically stable, low-symmetry IMo(V) site that possesses a coordination geometry between octahedral and trigonal prismatic and a surprisingly low degree of dithiolene character in the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) wavefunction. Electron and proton transfer to IMo(V) results in spontaneous loss of water to yield a five-coordinate Mo(IV) state. The work also provides detailed insight into the remarkably similar geometries of the Mo(V) intermediate, IMo(V), and the calculated Mo(IV) transition state that results from substrate binding. The Mo(IV)→Mo(VI) oxygen atom transfer process is found to be activationless using (CH3)3NO as the oxidizing substrate. This combined spectroscopic and computational study allows for a greater understanding of the relationship between des-oxo Mo(V) and Mo(IV) geometric and electronic structures, and how this contributes to the Mo(V)→Mo(IV)→Mo(VI) reaction coordinate, providing new insight into oxygen atom transfer and electron-transfer reactivity in members of the DMSOR enzyme family.

EXPERIMENTAL

DMSOR Purification

All chemicals and buffers were of the highest quality commercially available and were used without purification. Buffers were filtered prior to use and the pH was adjusted with HCl or NaOH. Rhodobacter sphaeroides strain 1632 was grown anaerobically under light exposure at 30 °C with malate as the carbon source and in the presence of 60 mM DMSO. Bacteria were harvested in late log phase (approx. 5th day) and stored until needed at −80 °C. DMSOR was purified as follows, with all purification steps performed at 4 °C unless otherwise noted. Approximately 60 g (wet weight) of Rhodobacter sphaeroides cells were thawed and washed three times with 240 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 containing 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.6 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.6 μg pepstatin A. The washed cells were then resuspended in 150 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.6 mM EDTA pH 8.0 with 0.6 μg pepstatin A. After addition of 100 mg of lysozyme, the suspension was incubated for 90 min at room temperature. Subsequent treatment with 12 mg each Dnase 1 and Rnase A and stirring at room temperature for additional 30 min afforded a thick viscous brown suspension, which was chilled on ice and passed through a French press (Thermo Electron Corporation) two times at 20,000 psi. 45.74 g of (NH4)2SO4 (40 %) was next added in small portions and stirred until dissolved. Note that 40% (NH4)2SO4 represents the percent saturation, assuming 700 g/L for a 100% saturated aqueous solution of ammonium sulfate. Spheroplasts and cell debris were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was treated with an additional 37.82 g of (NH4)2SO4 (70 %) and the suspension ultracentrifugated at 100,000 × g for 30 min. In order to avoid structural heterogeneity at the active site of DMSOR, the enzyme was “redox-cycled”.33 During this procedure Mo(VI) in the active site is reduced to Mo(IV) with subsequent reoxidation back to Mo(VI). The process involved resuspending the pellet in 30 mL of suspension buffer (0.5 mL/g cells), after which it was transferred to a serum-stoppered vacuum flask with 100 μM methyl viologen and made anaerobic under an argon stream for 1 h with slow constant stirring. A solution of freshly prepared 100 mM sodium dithionite solution in anaerobic 50 mM Tris base was titrated via microsyringe into the suspension until the intense blue color of reduced methyl viologen persisted. Anaerobic, neat DMSO (14.1 M) was then carefully titrated in, which elicited a brown-orange color corresponding to the Mo(VI) oxidation state. The crude extract was diluted fourfold with suspension buffer and dialyzed overnight against same. The next day the extract was loaded on a 2.6 × 40 cm Q Sepharose ion exchange column and eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl using a GE ÄKTApurifier FPLC instrument. Fractions containing DMSOR, as evidenced by their gray color, were concentrated to 8 mL and loaded on a size exclusion (S-200) column with 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 6 buffer, containing 0.6 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mM PMSF. After concentration, the purified DMSOR was frozen in liquid nitrogen as ~50 μL balls and stored at − 80 °C.

Preparation of the DMSOR Mo(V) Catalytic Intermediate

It has been shown previously that turnover of DMSOR with the alternate substrate (CH3)3NO and sodium dithionite as non-physiological reductant results in near-quantitative amounts of the species giving rise to the so-called “high-g split” EPR signal that is known to arise from a catalytically relevant intermediate.34 To prepare EPR and MCD samples of this species, several balls of the frozen as-isolated DMSOR (as described above), were thawed and centrifuged for at least 10 min to remove any insoluble material. The enzyme solution was placed into a quartz cuvette and made anaerobic on ice under a stream of argon gas for at least 1 h. The concentration of the DMSOR was determined to be 1.6 mM using a molar extinction coefficient ε = 2000 mM−1 cm−1 at 720 nm. The reaction was carried out in 1.0 mL cryogenic storage vials encased in ice. To determine the concentration of freshly prepared dithionite solutions, a stock solution (~250 mg of sodium dithionite powder per 10 mL of anaerobic 50 mM Tris base) was titrated against a standard solution of 0.2 mM dichlorophenolndophenol (DCIP) in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.0 containing 0.6 mM EDTA . The concentration of the ditihonite solution was calculated to be 148 mM using a molar extinction coefficient ε = 23 mM−1 cm−1 at 600 nm. 150 mM (CH3)3NO solution in 50 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM EDTA pH 6.0 buffer was made anaerobic under an argon stream prior to sample preparation. UV/Vis absorption spectra were obtained using a Hewlett-Packard 8452 diode-array spectrophotometer.

Neat ethylene glycol proved to be an ideal glassing agent for DMSOR MCD samples since it resulted in clear, non-cloudy optical glasses (with, e.g. polyethylene glycol, neat and mixed in various ratios with buffer, cloudiness upon freezing proved problematic). Ethylene glycol was first degassed in a round-bottomed flask and then by repeated freeze-pump-thaw cycles (at least seven) and stored on ice. 40 μL of DMSOR solution was carefully placed on top of the 80 μL of ethylene glycol in a cryogenic vial on ice and 12 μL (CH3)3NO was carefully added via microsyringe as a drop on the side, as was 50 μL of the 148 mM dithionite stock solution. The vial was gently swirled for a few seconds while remaining on ice and the two separated layers were rapidly mixed together using a cold (0 °C) glass stirring rod. After the mixture was homogenized, the reaction solution was rapidly transferred to a glass syringe and the MCD quartz window cell filled and immediately frozen by immersion in liquid N2. While immersed in liquid N2, the sample cell was placed on the end of the cryostat sample rod and quickly transferred into the 80 K sample space of an Oxford Instruments SMT- 4000 magnetooptical cryostat. The reaction mixture used in these experiments results in oxidation of the reduced Mo(IV) form of the enzyme by the (CH3)3NO substrate. The resulting oxidized Mo(VI) state is then reduced by the non-physiological reductant dithionite.

EPR Spectroscopy

EPR spectra of DMSOR were collected at X-band (9.3 GHz) using a Bruker EMX spectrometer with associated Bruker magnet control electronics and microwave bridges. Low-temperature enzyme spectra were collected in ethylene glycol, and the temperature was controlled using an Oxford Instruments liquid helium flow cryostat. Simulations of the EPR spectra were performed using the program X-Sophe and the matlab toolbox EasySpin,35 with further analyses performed using in-house written scripts for the program Visual Molecular Dynamics.

Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy

Electronic absorption spectra were collected using a Hitachi U-3501 UV–Vis–NIR dual-beam spectrometer capable of scanning a wavelength region between 185 and 3200 nm. DMSO reductase data were collected in buffer solutions, and the electronic absorption spectra were measured in a 1-cm pathlength, 100 μL, black-masked, quartz cuvette (Starna Cells, Inc.) equipped with a Teflon stopper. All electronic absorption spectra were collected at room temperature and repeated at regular time intervals to ensure the stability and integrity of the enzyme.

Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Low-temperature MCD spectra were collected using an MCD instrument that employs track mounted Jasco J-810 (185 – 900 nm) and Jasco J-730 (700 - 2000 nm) spectropolarimeters. This allows MCD data for a sample to be collected using a single Oxford Instruments SM4000-7T superconducting magnetooptical cryostat (0-7 T, 1.4-300 K) employing an ITC503 Oxford Instruments temperature controller. All spectra were collected at temperature intervals between 5 - 20 K in applied magnetic fields ranging from 0.0 - 7.0 Tesla. The spectrometer was calibrated for circular dichroism intensity with camphorsulfonic acid, and the wavelength was calibrated using Nd-doped glass. Depolarization of the incident radiation by the sample was determined by comparing the intrinsic circular dichroism of a standard Ni (+)-tartrate solution positioned in front of and then in back of each sample. Samples which were <7% depolarized were deemed suitable.

Computational Details

Spin-unrestricted gas-phase calculations for various DMSOR geometries were performed at the density functional level of theory using ORCA,36 ADF,37 and Gaussian 03W38 software packages. All Gaussian 03 calculations employed the B3LYP hybrid exchange-correlation functional.39 A 6-31G(d,p) basis set, a split valence basis set with added polarization functions, was used for all atoms. ORCA calculations used the B3LYP functional and a decontracted TZVP basis set. Input files were prepared using GaussView and ADF Input, as appropriate. Geometry optimizations, linear transit, and transition states were calculated with Gaussian 03. Orbitals derived from Gaussian 03 calculations were analyzed with the program AOMix.40 EPR parameters were calculated at the DFT level using ADF2009.0137,41,42 and ORCA 2.7.0.36,43-45 MCD spectra were calculated using both TD-DFT based46 and multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI, ORCA 2.7.0)36 methods. ADF EPR calculations used a triple-zeta basis set (TZP in the ADF basis set notation) and the PBE GGA density functional. Relativistic corrections were incorporated self-consistently in the ADF and ORCA calculations with the ZORA scalar relativistic Hamiltonian.41,47 MRCI calculations were performed with the spectroscopy oriented configuration interaction (SORCI)48 MRCI functionality in ORCA 2.7.0. Unless otherwise noted, all SORCI calculation settings were left at the default values. Natural orbitals (UNOs) from a DFT calculation (triple-zeta basis set49; PBE functional) were selected as the starting orbitals for the calculations. The calculation of the MCD spectrum was carried out with two separate SORCI calculations. First, an 11 electron, 11 orbital (orbitals with >10% molybdenum character) SORCI calculation was performed with loose cutoff values (Tpre = 1×10−1, Tsel = 1×10−5), the results of which calculated the orbitals necessary to accurately describe the excited states of interest. With this new active space, a 15 electron, 12 orbital calculation was completed using the default cutoff values (Tpre = 1×10−4, Tsel = 1×10−6, Tnat = 1×10−5). MCD and electronic absorption spectra were also calculated using both DFT (ADF) and ab initio based configuration interaction methods. Molecular orbitals and g-, and A-tensor orientations were visualized using VMD50 and the built-in Tachyon ray-tracer.51

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Geometry and Nature of the Ground State Wavefunction for IMo(V)

The low-temperature (29 K) X-band (~9 GHz) EPR spectrum of the catalytically relevant “high-g split” Mo(V) intermediate of DMSOR trapped using (CH3)3NO as substrate is presented in Fig. 2. We emphasize here that an identical EPR signal is observed in the course of turnover with DMSO and (CH3)3NO,3 accumulating initially to approximately 50% of the total enzyme in the case of DMSO and 100% in the case of (CH3)3NO. The lower accumulation of the signal-giving species in the course of turnover with DMSO is entirely due to rebinding of product DMS as it accumulates in the course of turnover to the oxidized enzyme, which drives the reaction back to the E(red)•DMSO intermediate, reducing the accumulation of the desired Mo(V) intermediate. In order to avoid this phenomenon, we have used (CH3)3NO rather than DMSO in preparing the signal-giving species. The IMo(V) EPR spectrum observed with (CH3)3NO as substrate is very intense and well resolved, and the spectrum clearly shows both 1H and 95,97Mo hyperfine splitting. The rhombic nature of the g-tensor anisotropy indicates the presence of a low-symmetry coordination environment for the signal-giving species, and this necessitates the use of an orthorhombic or lower-symmetry spin-Hamiltonian in simulations of the EPR spectra.

| Equation 1: |

Here, g is the g-tensor, β is the Bohr magneton, B is the applied magnetic field, An are the nuclei-specific hyperfine coupling tensor (n = 95,97Mo, 1H), is the electron spin operator, and is the nuclear spin operator. The 95,97Mo hyperfine tensor, AMo, is comprised of the isotropic Fermi contact term, , the spin dipolar term, , and the orbital dipolar term, , the latter of which is typically small.52 Although is proportional to the spin density at the nucleus of interest, the anisotropic term results from the spatial distribution of the spin density around the Mo nucleus. Therefore, the anisotropy in contains valuable information regading the nature of the singly-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) wavefunction.

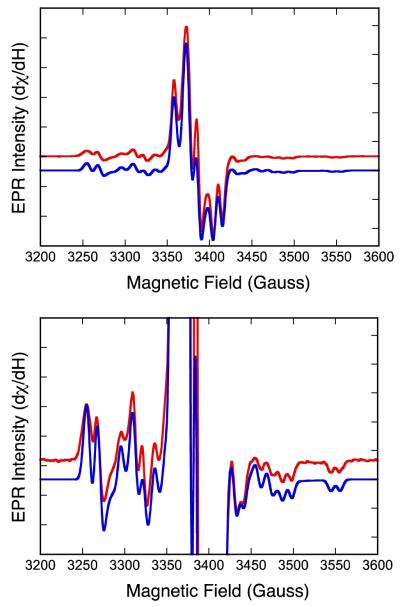

Figure 2.

Top: X-band EPR of the “high-g split” resonance observed for the DMSOR intermediate with (CH3)3NO as substrate (red) and spectral simulation (blue). Bottom: Expanded y-axis view of Top spectrum showing splitting due to 95,97Mo and 1H nuclei. Spectral parameters are given in Table 1.

The best simulation of the EPR spectra, obtained using the parameters given in Table 1, is shown in Figure 2 (blue). The spectral simulation yields 1H hyperfine and anisotropic g-values similar to those reported previously for this signal.53,54 The simulation also yields an unusual rhombic 95,97Mo hyperfine tensor with AMo = [13.33, 37.33, 52.00] × 10−4 cm−1, permitting AMo to be recast in terms of and . Interestingly, the anisotropic term does not resemble the familiar axial dipolar forms for either a true Mo(z2) ground state, , or a Mo(xy) ground state .55 Instead, is essentially in the rhombic limit where . The rhombic nature of reflects a des-oxo active site intermediate of low symmetry and a SOMO wavefunction that is not observed for oxo-Mo(V) sites in enzymes and model compounds. In fact, the near rhombic limit of indicates that the SOMO wavefunction may not clearly resemble any of the five canonical d-orbital functions in either Oh or D3h symmetry.

Table 1.

EPR Spin-Hamiltonian Parameters for IMo(V) and 1

| g-tensor | 95,97Mo A-tensor (x 10−4cm−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g1 | g2 | g3 | A1c | A2c | A3c | Aiso | |

| Experimental | 1.9988 | 1.9885 | 1.9722 | −20.89 | 3.11 | 17.78 | 34.22 |

| DFT: ADFa | 1.9923 | 1.9839 | 1.9700 | −12.87 | −0.23 | 13.1 | 20.58 |

| DFT: ORCAb | 1.9815 | 1.9620 | 1.9459 | −19.40 | 0.15 | 19.25 | 33.96 |

BP86/TZP

B3LYP/decontracted TZVP

values.

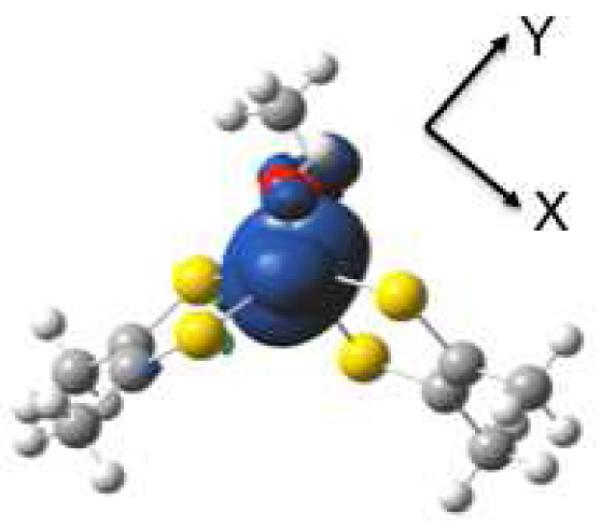

Since the intermediate responsible for the high-g split EPR signal accounts for ~100% of the species present under steady-state conditions using (CH3)3NO as substrate,3 we have explored the possibility that the Mo(V) intermediate possesses a relaxed geometric structure and does not represent an entatic, or high-energy state along the reaction coordinate. Therefore, we performed a full geometry optimization on [Mo(OMe)(S2C2Me2)2(OH)]1− (OMe = methoxy), 1, a computational model for this intermediate, in order to determine the energy-minimized structure and the nature of the spin-bearing singly-occupied redox-active orbital (SOMO). These calculations reveal an energetically stable low-symmetry geometry for model 1 that lies between idealized octahedral and trigonal prismatic. In order to develop deeper insight into the nature of the redox-active orbital, we have calculated the spin density distribution, relevant atomic spin populations, and the fragment orbital compositions for the β-LUMO wavefunction (Table 2), which is the approximate spatial counterpart to the α-HOMO. The nature of the β-LUMO redox orbital is important to our understanding of the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) redox process, since it is the β-LUMO that becomes occupied upon one-electron reduction to form the Mo(IV) state. The calculations show that the β-LUMO for 1 is largely localized on the Mo atom (~70%), and possesses only a small amount of dithiolene S character (~9% total). The spin density distribution calculated for 1 resembles the β-LUMO wavefunction and is presented in Figure 3. As expected for a Mo(V) site, the spin population on the Mo center is dominant (97%) with a sizable positive spin population (10%) localized on the oxygen atom of the methoxy donor that arises from spin delocalization. The calculations also reveal that the dithiolene sulfur spin populations are negative (-13% total). This is an interesting result, and we can use a simple CI argument that is based on a two-electron orbital description to provide an explanation of this observation. In a spin-restricted formalism, the spin density is equal to the square of the SOMO wavefunction, and this will always yield a positive spin density. Full CI optimization of a multideterminetal wavefunction can be greatly simplified if one only considers a few important excited configurations. Here we take into account low energy charge transfer configurations that result in negative spin populations on the dithiolene S atoms. These are the Sdithiolene→Mo ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) configurations that derive from Sdithiolene→Mo ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) states that are formed from promotion of an α (spin-up) electron localized on a sulfur-based ditholene MO into unoccupied Mo-based orbitals. The resulting localized triplet on the Mo ion (i.e. a configuration; where S is a dithiolene S orbital, the overbar represents a spin down electron in an orbital, d1 is the singly occupied Mo d orbital, and the dn are higher energy unoccupied Mo d orbitals) is lower in energy than the localized singlet ( configuration) that results from promotion of a β (spin-down) electron localized on a dithiolene S into unoccupied Mo-based orbitals due to the exchange energy. Thus, admixture of the configuration dominates over admixture of the configuration into the ground state, leading to a negative spin population on S. Within this model, a large covalency between the Mo redox orbital and the dithiolene sulfur donors would result in an appreciable contribution from the low energy configuration. This would result in intense Sdithiolene→Mo CT transtions to the d1 acceptor orbital and a dominant positive spin population on the sulfur donors, which are contrary to our observations.

Table 2.

Fragment Orbital Composition (β-LUMO) and Spin Populations for 1.

| Molecular Fragment |

Mo | -OH | -OCH3 |

Sdithiolene (P-pterin) |

Sdithiolene (Q- pterin) |

Dithiolene (P-pterin) |

Dithiolene (Q-pterin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-LUMO (%) | 69.6 | 4.6 | 10.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 8.4 |

| Spin Populationa |

+97.0 | +3.1 | +9.0 | −5.6 | −7.6 | - | - |

Spin populations are listed for atoms in italics. For Sdithiolene, the spin populations are the sum of that for both dithiolene sulfur atoms. Spin populations calculated with G03. Fragment compositions calculated with AOMix.

Figure 3.

Calculated spin density distribution for 1. Positive spin density (blue) is largely localized on Mo with a small negative spin density (green) on the dithiolene sulfurs. View is oriented down the molecular z-axis. Spin density calculated using Gaussian 03.

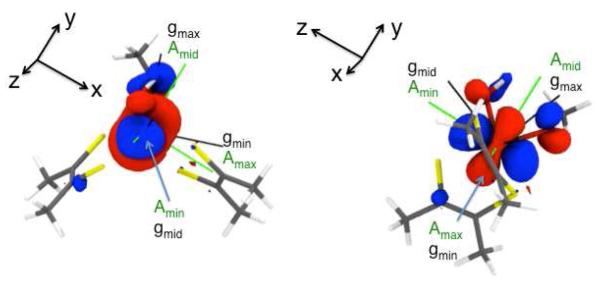

We have also computed the spin-Hamiltonian parameters for geometry-optimized 1 in order to make a direct comparison with the experimentally determined g and AMo EPR parameters that we obtained for IMo(V) in order to assess whether a relaxed enzyme intermediate structure such as that calculated for 1 is consistent with the IMo(V) EPR data. The calculations reveal g tenor components in excellent agreement with experiment and a rhombic 95,97Mo hyperfine tensor, AMo = [14.55, 34.10, 53.20] × 10−4 cm−1 with a corresponding dipolar component, , that is also in excellent agreement with the experimental values (Table 1). Calculations indicate that the smallest hyperfine component, , is associated with gmid, the middle g-value. Figure 4 shows the principle components of the calculated g tensor and the experimental AMo tensor superimposed upon the β-LUMO wavefunction. In this orientation (Figure 4, left), the β-LUMO wavefuntion resembles a Mo(z2) orbital with an oval-shaped, instead of circular, “doughnut” in the x-y plane. If the β-LUMO is rotated 90° with respect to the axis (Figure 4, right), the β-LUMO now resembles a Mo(y2-z2) type orbital. Here, the largest hyperfine component, , is associated with gmin, the smallest g-value.

Figure 4.

Principal components of the computed AMo- (green) and g-(black) tensors for the “high-g split” resonance shown superimposed on the DFT calculated SOMO wavefunction (singly occupied quasi-restricted molecular orbital (QRO). The left and right figures are related by a 90° rotation about the y-axis.

In summary, there is very good agreement between the experimental and computed g, AMo, and parameters (Table 1) indicating the ground state electronic structure and the calculated geometry for 1 closely mimics that of IMo(V). Both the experimental and calculated EPR spin-Hamiltonian parameters are consistent with a low-symmetry structure for IMo(V). The g tensor components are all less than the free ion value (2.0023), suggesting a low-degree of Mo-Sditholene covalency in the redox-active orbital and the g tensor indicates a relaxed, rather than entatic, geometry for this intermediate. Such a relaxed geometry for IMo(V) is consistent with the results of prior kinetic data on DMSOR where, using (CH3)3NO as substrate, the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) reduction step is observed to be rate-limiting for turnover.3 This suggests that the relative stability of IMo(V), as reflected in the extent to which it accumulates during turnover, contributes substantially to a high energy transition state for the coupled electron-proton process along the reaction coordinate (Figure 1) that is associated with the reduction of Mo(V)-OH on to Mo(IV) + H2O. In order to further examine excited state contributions to the electronic structure of IMo(V) in greater detail, we have collected electronic absorption and magnetic circular dichroism data on the enzyme intermediate and made detailed spectral assignments for the observed optical transitions.

Excited State Spectroscopic Probes of I Mo(V)

Electronic Absorption and MCD Spectroscopy

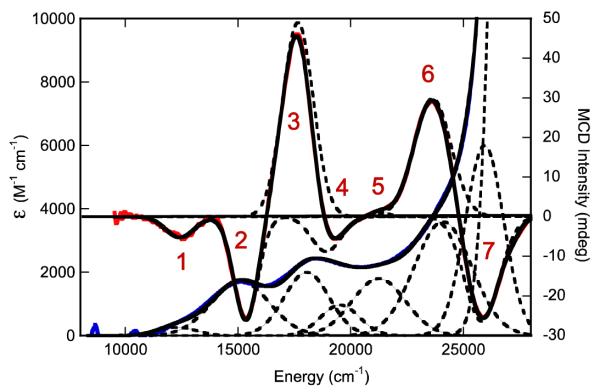

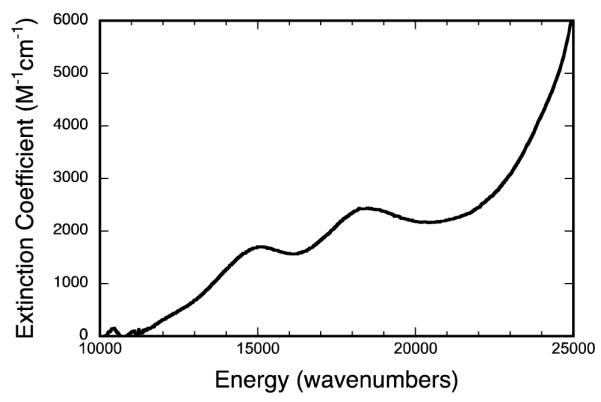

The electronic absorption spectrum for IMo(V) at 300K is given in Figure 5. Three low-energy bands in the NIR-visible region of the spectrum are observed at 12,150 cm−1 (ε = 458 M−1cm−1, shoulder), 14,960 cm−1 (ε = 1,710 M−1cm−1) and 18,525 cm−1 (ε = 2,500 M−1cm−1). A slight shoulder is also apparent along the high-energy rising absorption edge at ~24,260 cm−1. Although the absorption spectrum of IMo(V) is similar to that previously reported for the glycerol-inhibited enzyme,56 some key differences are evident. Namely, the 12,150 cm−1 band was not previously observed in the absorption spectrum of the glycerol-inhibited enzyme,56 and the 14,960 cm−1 and 18,525 cm−1 bands are shifted to slightly higher energy (<1000 cm−1) for IMo(V) compared to the glycerol inhibited spectrum. Also, the shoulder observed at ~24,260 cm−1 in the intermediate is clearly resolved in the glycerol inhibited enzyme at approximately the same energy. The energies and intensities of the observed bands in the electronic absorption spectrum are consistent with their general assignment as Sditiholene→Mo LMCT transitions.

Figure 5.

300K electronic absorption spectra of the physiological “high-g split” Mo(V) species (IMo(V)).

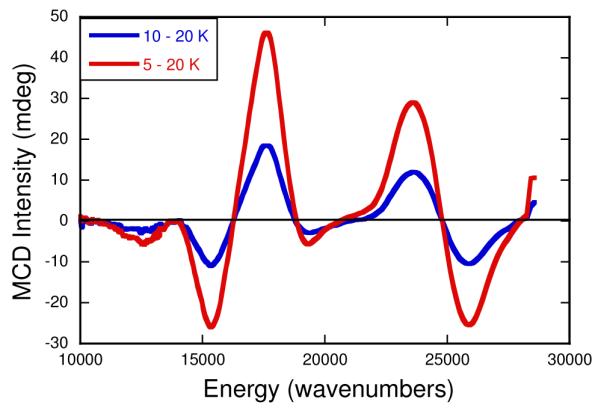

Variable-temperatue MCD spectroscopy provides a higher resolution probe of the excited state electronic structure. MCD spectra collected at 5K, 10K, and 20K are plotted as temperature difference spectra in Figure 6 and these reveal seven temperature dependent C-term bands between 10,000 – 27,000 cm−1. In an idealized trigonal prismatic geometry (D3h) with equivalent donor atoms, the Mo d-orbitals split, in order of increasing energy, into Mo(z2) (a1’), Mo(x2-y2, xy) (e’), and Mo(xz, yz) (e”) levels.19 The degeneracies of the e’ and e” orbitals are also preserved in the twisted D3 geometry (i.e. a1, e, e) that is intermediate between Oh and D3h. Although the nature of the IMo(V) SOMO wavefunction indicates a Mo(z2) type ground state, the rhombic nature of the EPR spectrum suggests low-symmetry distortions from idealized trigonal symmetry, and this will result in a splitting of the doubly degenerate metal-based orbitals and corresponding excited states. The temperature dependent MCD spectra for IMo(V) show the presence of both C-terms and temperature-dependent pseudo-A terms.57-59 MCD pseudo-A terms are C-terms of opposite polarization (sign) that derive from transitions to orbitally nearly degenerate or nearly degenerate excited states that possess strong in-state spin-orbit coupling. LMCT transitions in IMo(V) that involve one electron promotions to orbitals of e parentage result in 2E excited states that are subject to a strong in-state spin-orbit coupling and corresponding pseudo-A term behavior. The appearance of an apparent positive pseudo-A term centered at ~ 16,300 cm−1 and a higher energy negative pseudo-A term centered at ~ 24,800 cm−1 in the MCD spectra of IMo(V) strongly suggests that these spectral features result from LMCT transitions to Mo-based acceptor orbitals that derive from doubly degenerate 2E states in a trigonal basis. Finally, the lowest energy band appearing at 12,375 cm−1 appears as a negative C-term, and is in an energy region where ligand field (LF) bands have been observed in Mo(IV) bis-dithiolene compounds.23

Figure 6.

Variable-temperature MCD data for the physiological “high-g split” Mo(V) species (IMo(V)). The data, which were collected at 7T, are displayed as 5-20K (red) and 10-20K (blue) difference spectra.

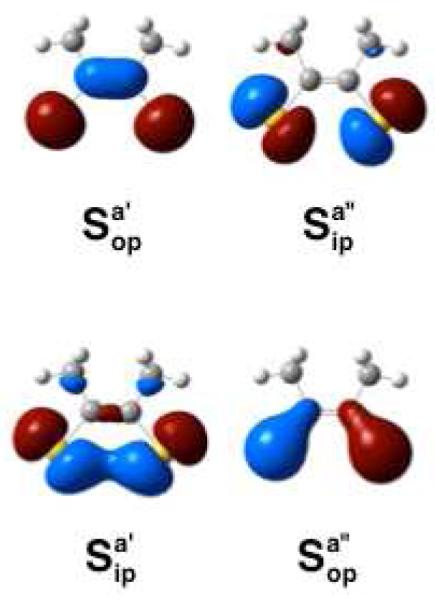

Dithiolene Frontier Molecular Orbitals

The principal occupied ene-1,2-dithiolate (dithiolene) ligand MOs contributing to the frontier molecular orbital scheme and spectroscopy of metallo-bis(dithiolene) systems19 are shown in Figure 7. The symmetric out-of-plane orbital is delocalized over the S-C=C-S backbone and is the highest energy filled dithiolene orbital owing to the two S(p)-C(p) π* antibonding interactions.19 As a result of the C=C orbital contribution to , the energy of this orbital is expected to be sensitive to the pyranopterin ditholene environment in DMSOR. In contrast, the , is almost entirely localized on the two sulfur donors. The lack of S(p)-C(p) π* antibonding interactions in this orbital results in it being stabilized by ~4,400 cm−1 relative to . The dithiolene and orbitals are considerably more stabilized relative to due to C=C and S-S bonding interactions in , and two C-S S(p)-C(p) π bonding interaction in . Due to its high relative energy, is expected to contribute significantly to the highest-energy occupied MOs in IMo(V). Therefore, the lowest energy LMCT transitions in IMo(V) should involve one-electron promotions from ligand-based orbitals with appreciable character to the lowest-energy Mo based acceptor orbitals.

Figure 7.

Highest energy occupied [S2C2Me2]2− (dithiolene) molecular orbitals. Sulfur atomic orbital combinations are labeled as either in-plane (ip) and out-of-plane (op) with respect to the plane of the page. Symmetry labels are listed with respect to C2v ligand symmetry. Relative orbital energies: ; ; ; .

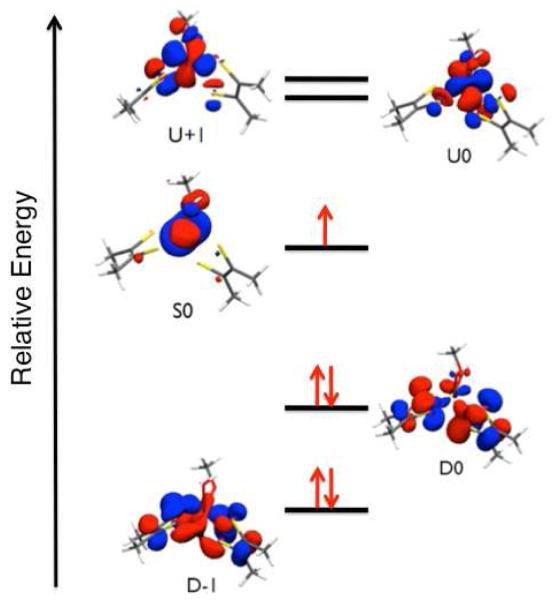

Frontier Molecular Orbital and Bonding Description for 1

The 12 calculated natural orbitals that define the active space for our SORCI calculations (vide infra) are listed in Table 3, and the relevant frontier natural orbitals are shown in Figure 8 and Figure S1. Except for D-5 (Figure S1), which possesses appreciable –OMe orbital character, all of the doubly occupied frontier molecular orbitals are dominantly (i.e. >50%) ditholene in character (Table 3; Figure S1). As anticipated from the description of the dithiolene MOs in Figure 7, the highest energy doubly occupied orbitals, D0 and D-1, are constructed from (−) and (+) linear combinations of two dithiolene orbitals, respectively. The spatial nature of the singly occupied S0 orbital is analogous to the β-LUMO (Table 2) that was derived from the spin-unrestricted calculations employed in the EPR analysis. The S0 Mo-based orbital (77% Mo) possesses only 6% Sdithiolene character and can be associated with the formally non-bonding and non-degenerate a’ Mo(z2) orbital in an idealized trigonal prismatic geometry. The results of the EPR analysis and the observed small degree of Sdithiolene character in S0 suggest that LMCT transitions to S0 will possess low to moderate oscillator strengths and are not expected to dominate the electronic absorption spectrum of IMo(V). The unoccupied Mo-based orbitals U0 and U+1, which correspond to the degenerate e’(π*) orbital set in trigonal symmetry, are π antibonding with respect to the ligands. Similarly, the higher energy U+2 and U+3 e”(σ*) type orbitals are found to be σ antibonding with respect to the ligands (Figure S1). The increased Sdithiolene character in the U0 and U+1 orbitals relative to S0 results from the greater admixture of ligand character into these formally e(π*) metal orbitals. The character found in U0 and U+1 also results in relatively large ligand-ligand overlap densities with D0 and D1, and this contributes to appreciable absorption intensity for D→U LMCT transitions involving one-electron promotions between these orbitals.60

Table 3.

Fragment Orbital Löewdin Compositions (% character) for the SORCI Active Space Natural Orbitals for 1.a

| Natural Orbital |

Occupation Number |

Mo | OH | OCH3 | Sdithiolene (P- pterin) |

Sdithiolene (Q- pterin) |

Dithiolene (P-pterin) |

Dithiolene (Q-pterin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-6 | 1.98 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 31 | 35 | 37 | 54 |

| D-5 | 1.97 | 23 | 8 | 33 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 20 |

| D-4 | 1.97 | 23 | 5 | 23 | 29 | 16 | 32 | 17 |

| D-3 | 1.96 | 26 | 9 | 15 | 17 | 29 | 19 | 33 |

| D-2 | 1.96 | 31 | 2 | 3 | 28 | 32 | 30 | 34 |

| D-1 | 1.64 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 25 | 34 | 43 |

| D0 | 1.52 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 25 | 51 | 36 |

| S0 | 0.68 | 77 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| U0 | 0.61 | 70 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 13 | 8 |

| U+1 | 0.58 | 68 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 17 |

| U+2 | 0.08 | 66 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 18 |

| U+3 | 0.04 | 64 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 22 | 9 |

D = doubly occupied MO; S = singly occupied MO; U = unoccupied MO. All values from ORCA SORCI calculation.

Figure 8.

Subset of the active space natural orbitals used in SORCI calculations of the electronic absorption and MCD spectra for 1 (D = doubly occupied; S = singly occupied; U = unoccupied). Perspective view is looking down the pseudo 3-fold molecular “z” axis.

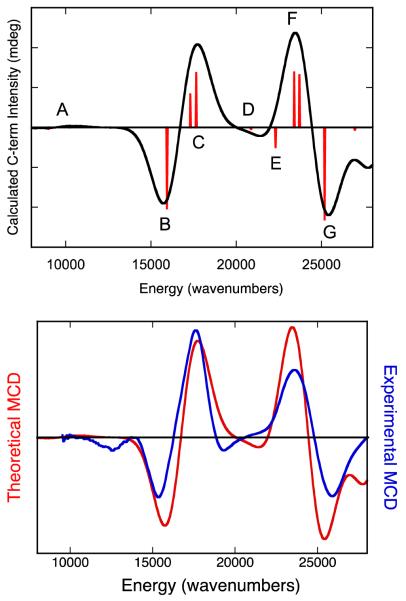

Band Assignments

The Gaussian-resolved electronic absorption and MCD spectra for IMo(V) are presented in Figure 9, where a near 1:1 correspondance between MCD and absorption features is observed (experimentally observed bands 1-7). The energies of these bands, as well as their calculated oscillator strengths, are summarized in Table 4. In order to assist the assignment of bands 1 – 7, we have used the SORCI method as implemented in ORCA to calculate oscillator strengths, MCD C-term intensities and signs, and transition energies for computational model 1. Although the SORCI method is a very computationally expensive method, these calculations very accurately reproduce the basic MCD C-term dispersion seen in the experimental spectrum of IMo(V) using a constant bandwidth and no energy scaling. The calculated MCD spectrum for 1 and its overlay with the experimental IMo(V) spectrum are shown in Figure 10. The individual transitions that contribute to the calculated spectral bands (A-G), the signs of the MCD C-terms, and the calculated transition energies and oscillator strengths are given in Table 5. Note that there are seven calculated bands for model system 1 (A-G) and seven experimentally observed bands for the enzyme intermediate, IMo(V) (1-7). For the calculated spectra, it is observed that only one or two electronic transitions contribute to any individual spectral band, and the dominant excitations in the 8,000 – 28,000 cm−1 range are all single excitations that derive from one-electron promotions between the U+1, U0, S0, D0, and D+1 orbitals.

Figure 9.

Overlay of the 300K electronic absorption (blue) and 7T, 4.5K magnetic circular dichroism (red) spectra for the physiological “high-g split” Mo(V) species (IMo(V)). Gaussian resolved spectral bands are presented as dashed lines and the composite spectra as black lines.

Table 4.

Summary of MCD and Electronic Absorption Bands for IMo(V).

| Energy | Oscillator Strength (f) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | MCD | Experimental | Calculated (SORCI) | |

| Band 1 | 12,250 | 12,375 | .002 | .002 (.001) |

| Band 2 | 15,050 | 15,375 | .024 | .010 (.006) |

| Band 3 | 18,080 | 17,660 | .023 | .061 (.028) |

| Band 4 | 19,550 | 18,920 | .009 | ~.001 (<.001) |

| Band 5 | 21,250 | 21,330 | .020 | .017 (.014) |

| Band 6 | 23,905 | 23,615 | .053 | .100 (.050) |

| Band 7 | n.a. | 25,895 | n.a.a | .020 (.010) |

Since no apparent maximum is observed in the electronic absorption spectrum of IMo(V), the oscillator strength of this band could not be accurately determined.

Figure 10.

Top: SORCI calculated MCD spectrum of 1 Red sticks are the individually calculated transtions that contribute to Bands A-G. Bottom. Overlay of the SORCI calculated (red) and experimental (blue) MCD spectra for “high-g split” Mo(V) species.

Table 5.

SORCI Calculated MCD and Electronic Absorption Parameters for 1.

| Band | Transition # | Transition Type |

Transition Energy |

MCD Sign | Oscillator Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | I | S0→U+1 | 9078 cm−1 | (−) | 2×10−4 |

| II | S0→U0 | 10,157 cm−1 | (+) | 9×10−4 | |

| B | III | D0→U+1 (57%) D0→U0 (18%) |

16,010 cm−1 | (−) | 0.006 |

| C | IV | D0→S0 | 17,396 cm−1 | (+) | 0.008 |

| V | D0→U0 (58%) D0→U+1 (22%) |

17,496 cm−1 | (+) | 0.02 | |

| D | VI | D0→U+1 (56%) D-1→U+1 (14%) |

20,890 cm−1 | (−) | 3×10−4 |

| E | VII | D-1→U0 (51%) D0→U0 (21%) |

22,316 cm−1 | (−) | 0.005 |

| F | VIII | D-1→S0 | 23,431 cm−1 | (+) | 0.009 |

| IX | D-1→U0 (38%) D-1→U+1 (20%) D0→U+1 (17%) |

23,714 cm−1 | (+) | 0.05 | |

| G | X | D-1→U+1 (52%) D-1→U0 (16%) |

25,124 cm−1 | (−) | 0.01 |

Prior to this study, MCD spectra were obtained for a glycerol-inhibited Mo(V) form of the R. sphaeroides enzyme56 and a partially reduced proton-split Mo(V) enzyme form from R. capsulatus that possessed 0.06 spins/Mo.61 Band assignments were made that suggested all of the observed transitions were Sdithiolene→Mo in nature. However, these assignments were made prior to the x-ray structure of the enzyme and on the assumption of a single pyranopterin dithiolene coordinated to the Mo center. Recently, a theoretical TDDFT study was performed on various Mo(V) computational models of the DMSOR active site which were based on the strucure of the oxidized Mo(VI)-oxo form of the enzyme, and the original glycerol-inhibited MCD spectra were reassigned.62 Here, we have collected the first MCD spectra on a bona-fide R. sphaeroides catalytic intermediate allowing for direct comparison with the glycerol-inhibited spectrum. We have used these data to evaluate the results of our SORCI calculations and to make assignments for all seven bands observed between 8,000 – 28,000 cm−1 in the MCD and electronic absorption spectra of IMo(V).

Band 1. Band 1 is the lowest energy band observed in the MCD and electronic absorption spectra of IMo(V). This band is observed as a negative C-term in the MCD spectrum at 12,375cm−1 and as a weak (f = .002) band in absorption spectrum at 12,250cm−1. We assign the band as the S0→U0/S0→U+1 ligand field excitation. This assignment is based, in part, on our observation of similar ligand field bands in the solution and low-temperature mull electronic absorption spectra of five-coordinate symmetrized models for the reduced des-oxo form of DMSOR.23 The low-temperature (11K) mull electronic absorption spectra of [Mo(OAd)(dt)2]1− (11,370 and 14,340 cm−1), [Mo(SAd)(dt)2]1− (11,640 and 13,880 cm−1), and [Mo(SeAd)(dt)2]1− (11,700 and 13,810 cm−1) (Ad = adamantyl) of these models display transition energies and the oscillator strengths of ligand field bands that are comparable (f ~ .001 per transition in the models) to Band 1 in IMo(V) (f ~ .002). Our calculations indicate that the ligand field transitions in IMo(V) should occur at energies of 9078 cm−1 (S0→U+1) and 10,157cm−1 (S0→U0) and display a positive pseudo-A term feature in the MCD. The observation of a single negative C-term likely indicates the presence of additional spin-orbit or configuration interaction perturbations not accounted for in the calculations that affect the nature of the experimentally observed ligand field transitions in the MCD, or that one of the ligand field bands is too weak to be observed. This low energy ligand field band was not reported in the earlier MCD study of Thompson and coworkers61 on the partially reduced R. capsulatus enzyme. However, a weak negative feature at 11,000 cm−1 was noted to occur in the MCD spectrum of the glycerol inhibited enzyme,56 but the data were not shown. This negative MCD band was tentatively suggested to be the lowest energy ligand field band.56 The 1,375 cm−1 energy difference in the observed ligand field bands for IMo(V) and the glycerol-inhibited enzyme bands derives from an apparent weaker ligand field for the glycerol inhibited enzyme, and this likely results from a combination of glycerol being coordinated at the inhibited active site and slightly different geometries for the inhibited enzyme and IMo(V). Although this ligand field band was not explicitly assigned in the TDDFT study of the DMSOR glycerol-inhibited spectrum, the authors indicated ligand field bands should appear at low energy and yield a positive pseudo-A term in the MCD.62

Bands 2 and 3. Bands 2 (fexp = 0.024) and 3 (fexp = 0.023) possess markedly higher oscillator strengths than Band 1 and appear as a positive pseudo-A term in the MCD spectrum of IMo(V). Band 2 appears at 15,050 cm−1 in the absorption spectrum and 15,375 cm−1 in the MCD, while Band 3 appears at 18,080 cm−1 in the absorption spectrum and 17,660 cm−1 in the MCD. With our assignment of Band 1 resulting from S0→U0/S0→U+1 ligand field excitations, Bands 2 and 3 represent the two lowest energy LMCT bands in IMo(V). We attribute the positive pseudo-A term behavior of Bands 2 and 3 in IMo(V) as arising from strong spin-orbit mixing of excited states that derive from D0→U+1 and D0→U0 (Band B and transition V of Band C; Figure 10 and Table 5) one-electron promotions to the pseudo-degenerate U0 and U+1 dπ* Mo based orbitals. In idealized trigonal prismatic geometry the U0 and U+1 orbitals comprise a degenerate e(π*) orbital set. Therefore, this low energy pseudo-A term formally derives from a 2A→2E transition in high-symmetry. In support of this assignment, similar dithiolene→Mo(dπ*) LMCT transitions were assigned in the symmetrized des-oxo Mo(IV) model systems which occur at energies greater than 15,000 cm−1.23 Additionally, the calculated oscillator strengths (Band 2, ftheory = 0.006; Band 3, ftheory = 0.020) are in reasonable agreement with experiment. Interestingly, the SORCI calculations indicate that the D0→S0 excitation, which results in double occupancy of the singly occupied S0 redox orbital, is also present in this energy region (Table 5) and contributes to the Band 3 bandshape and intensity. The assignment of the D0→S0 excitation is important, since this transition directly probes the nature of the S0 redox orbital. Strong electron-electron repulsion is anticipated when the S0 orbital becomes doubly occupied due to the relatively non-covalent (~6% dithiolene S character) nature of the S0 orbital in IMo(V), and this explains why the D0→S0 excitation is calculated at higher energy than D0→U+1. The calculations also indicate that the inherent intensity of the D0→S0 excitation is weak (ftheory = 0.001), as anticipated for an acceptor orbital that possesses a small degree of ligand character, but derives significant intensity (ftheory = 0.008) via spin-orbit mixing with the D0→U0 excitation. The analysis of the glycerol-inhibited MCD spectrum resulted in the corresponding negative and positive MCD bands in this energy region being assigned as D0→U0 type excitations involving α (positive C-term) and β (negative C-term) one-electron promotions to the acceptor orbital.62

Band 4. Band 4 appears as a negative MCD C-term band and possesses a weaker experimental oscillator strength (fexp = 0.009) than that observed for either Band 2 or Band 3. Band 4 also corresponds to the negatively-signed C-term Band D found in the SORCI calculations (D0→U+1 (56%); D-1→U+1 (14%)). By comparison, the negative MCD feature in the glycerol inhibited spectrum was suggested to be the dominant contibutor to the oscillator strength of the ~18,000 cm−1 absorption feature (i.e. Band 3 in IMo(V)) and arise from two excitations that derive from D0→U+1 and D-1→S0 one-electron promotions.

Band 5. Band 5 is a very weak positive MCD C-term band in IMo(V) that occurs at 21,330 cm−1 with an experimental oscillator strength of fexp = 0.020. A similar, albeit more pronounced, positive C-term band is also observed in the glycerol-inhibited spectrum but the transition has never been assigned. Our results indicate that this transition arises from an overlap and near cancellation of the negatively signed C-term transition VII (D-1→U0 (51%); D0→U0 (21%)) of Band E and the positively signed C-term transition VIII (D-1→S0) of Band F. Additional support for this assignment comes from the fact that the combined calculated oscillator strength (ftheory = 0.014) for transition VII of Band E and transition VIII of Band F is in good agreement with the experimental oscillator strength.

Bands 6 and 7. Bands 6 (fexp = 0.053) and 7 (fexp = n.d.) appear as a negative pseudo-A term in the MCD spectrum of IMo(V), and similarly signed MCD bands are observed in both the glycerol-inhibited R. sphaeroides and partially reduced R. capsulatus enzymes. With respect to our assignment of Bands 2 and 3, which were LMCT transitions involving one-electron promotions from the D0 orbital, we assign Bands 6 and 7 in IMo(V) as arising from transitions that are predominantly linear combinations of D-1→U0 and D-1→U+1 excitations (transition IX of Band F and Band G). A pseudo-A term is anticipated from a 2A→2E transition in an idealized trigonal prismatic geometry, where the U0 and U+1 acceptor orbitals comprise the degenerate e(π*) orbital set. Since the acceptor orbitals (U0 and U+1) in these transitions are the same as those in Bands 2 and 3, the energy difference between the low-energy positive pseudo-A term (Bands 2 and 3) and the higher energy negative pseudo-A term (Bands 6 and 7) reveal an apparent spectroscopic splitting of ~8,000 cm−1 for the dithiolene based D0 and D-1 orbitals. The large D0 – D-1 orbital splitting results, in part, from a greater stabilization of D-1 due to the larger degree of Mo-S bonding character (23% Mo, 46% S character) in this orbital compared with D0 (12% Mo, 59% S character) (Table 3). In the glycerol inhibited enzyme, Band 6 was assigned as arising from both D-1→U0 and D-1→U+1 one-electron promotions, while Band 7 was assigned as arising from three excitations that derive from D-1→U0 and D-2→U0 one-electron promotions in addition to the ligand field excitation S0→U+3. The S0→U+3 ligand field excitation was also calculated to possess the highest oscillator strength of any transition in the entire glycerol-inhibited spectrum.62

In summary, all of the electronic transitions observed between 10,000 – 28,000 cm−1 in the electronic absorption and MCD spectra of IMo(V) can be assigned as arising from one-electron promotions between five frontier molecular orbitals (D-1, D0, S0, U0, and U+1). Our EPR, MCD, and electronic absorption data, evaluated in the context of detailed bonding and excited state calculations, indicate that a low-symmetry six-coordinate Mo(V) geometry is present in IMo(V). The lowest-energy band has been assigned as the lowest energy ligand field transition. Two intense pseudo-A term bands have also been assigned, arising from D0→U0/U+1 and D-1→U0/U+1 one-electron promotions. The U0 and U+1 orbitals derive from a doubly degenerate e(π*) orbital set in trigonal symmetry, leading to a large in-state spin-orbit coupling. The assignment of the two pseudo-A terms is significant, as they indicate the low-symmetry geometry derives from a trigonal distortion of the six-coordinate site. Our data also allow us to attribute the rate-limiting nature of the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) reduction step during turnover to a relaxed geometry and a concommitant energetic stabilization of IMo(V). A further contribution to the stability of IMo(V) could result from the small degree of Mo-Sdithiolene overlap in the S0 orbital. The small Mo-Sdithiolene overlap in S0 would lead to poor pyranopterin dithiolene mediated electronic coupling of the active site with exogenous redox partners and an energetic destabilization of the Mo(IV) state due to a large electron-electron repulsion in the now doubly occupied S0. With respect to pyranopterin mediated electronic coupling between the Mo site and exogenous redox partners, recent spectroscopic studies of a small molecule analogue of oxidized DMSOR have provided evidence that a single pterin may serve as a conduit for electron transfer in the Mo(VI)→Mo(V) step, and this results from a single dithiolene sulfur donor contributing approximately 18% sulfur character to the redox-active orbital.16 In this regard, it is noteworthy that for all DMSOR family enzymes that have been examined crystallographically and possess endogenous redox-active centers in addition to the molybdenum center, the nearest redox partner to the molybdenum lies to the Q pterin side of the center. Assuming the Q-pterin is indeed the physiological conduit for electron transfer regeneration in DMSOR, the U+1 orbital may play a significant role in the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) electron transfer process by contributing to an overall increase in electronic coupling between the Mo ion and the dithiolene component of the Q-pterin since this orbital possesses approximately five times the Q-pterin dithiolene sulfur character as the S0 orbital. We note that there would be an energetic penalty for utilizing the U+1 orbital in the electron transfer regeneration step since it resides at higher energy than S0. However, this energy may be reduced due to the increased electron-electron repulsion that accompanies double occupation of S0 and associated electronic relaxation effects. Finally, we note that differences in MCD spectral assignments between the glycerol-inhibited enzyme and the IMo(V) catalytic intermediate likely result from the different computational methods used (TDDFT and SORCI) as well as the inherent differences between the two sites.

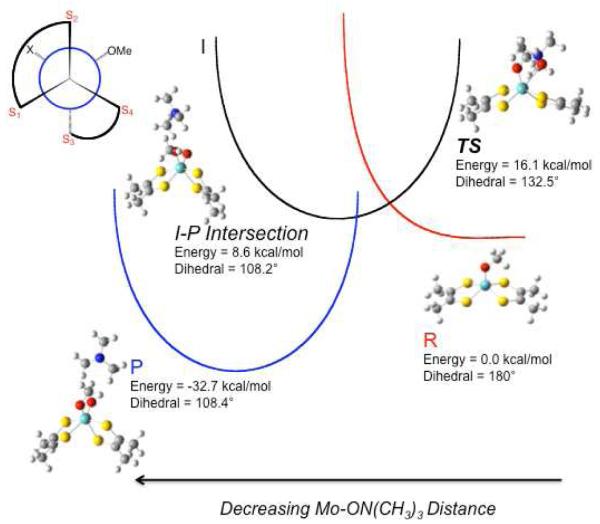

Relationship Between IMo(V) and the Transition State for Oxygen Atom Transfer

In order to proceed beyond the stable IMo(V) (Mo(V)-OH) state in the catalytic cycle, an electron-proton transfer step is required in order to form the catalytically competent Mo(IV) + OH2 state. The water molecule generated upon reduction of the Mo(V) site must be labile in order for an associative type oxygen atom tranfer mechanism to occur between the (CH3)3NO substrate and the Mo(IV) site. Gas phase geometry optimizations of six-coordinate [Mo(dithiolene)2(OMe)(OH2)]1− (2) result in spontaneous loss of water to form a stable 5-coordinate [Mo(dithiolene)2(OMe)]1− (3) species that possesses a square pyramidal (SP) geometry. Interestingly, labilization of metal-bound water is also observed when the dithiolene dihedral angle is fixed at 122°, as in the high-g split computational model 1. Thus, it appears that protonation of the Mo(V) hydroxyl coupled with a one-electron reduction of the metal is sufficient to labilize the coordinated water even when the geometry is not allowed to relax to the SP minimum. Low-symmetry distortions from the SP geometry of 3, which involve either a reduction in the 180° SP dithiolene dihedral angle and/or a tilting of the apical serinate oxygen off of the SP z-axis, have been shown to increase the energy of the Mo(IV) state and are likely to contribute to a reduction in the activation energy for oxygen atom transfer by raising the energy of the five-coordinate catalytically competent Mo(IV) site.23 Our EPR, electronic absorption, and MCD spectroscopic studies of IMo(V) have been used to probe the geometry and electronic structure of the six-coordinate Mo(V)-OH state and may also be used to provide insight into the putative six-coordinate transition state geometry of the enzyme.

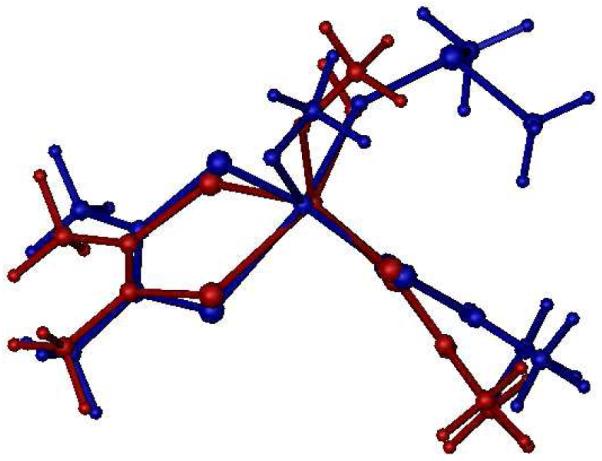

In order to understand the relationship between the spectroscopically derived coordination geometry for IMo(V) and the transition state for oxygen atom transfer between Mo(IV) and (CH3)3NO, we have explored the reaction coordinate computationally and the results are depicted in Figure 11. Here, three intersecting potential energy surfaces, representing reactant (R: 3 + (CH3)3NO)), intermediate (I: 3-ON(CH3)3), and product (P: [MoO(dithiolene)2(OMe)]1− + (CH3)3N), reflect the nature of the enzyme reaction coordinate. The TS in the reaction with (CH3)3NO as substrate is very similar to the first transition state calculated with DMSO as substrate,30,31 and is best described as a formally six-coordinate Mo(IV) species with nascent Mo-Osubstrate bond formation (d(Mo-Osubstrate) = 2.74Å). In Figure 12 we show an overlay of the IMo(V) structure that is consistent with our EPR, MCD, and electronic absorption studies, and the calculated structure of TS. Inspection of Figure 12 shows the geometric differences between these two structures are minimal, with a dithiolene dihedral angle of 132.5° in the calculated TS compared to the 122° dihedral determined for IMo(V). Furthermore, the calculated root mean square deviation (RMSD) of first coordination sphere ligand positions is only 0.19Å. No stable intermediate was found using (CH3)3NO as substrate, which is consistent with the enzyme studies.3 However, a point is found on the potential energy surface where the individual I and P surfaces intersect (I-P Intersection in Figure 11 and Figure S2). The I-P intersection is the point where the substrate N-O bond breaks, resulting in initial Mo≡Ooxo bond formation (d(Mo-Ooxo) = 2.15Å) that eventually leads to a minimum on the potential energy surface P with complete formation of the Mo≡Ooxo bond of the oxidized Mo(VI) center.

Figure 11.

Qualitative reaction coordinate of DMSOR with (CH3)3NO as substrate showing reactant ( ), intermediate (I), and product (

), intermediate (I), and product ( ) potential energy surfaces. The transition state is defined as TS. This reaction coordinate is based on the calculated reaction coordinate shown in Figure S2. Dihedral angle is defined as S1-S2-S3-S4.

) potential energy surfaces. The transition state is defined as TS. This reaction coordinate is based on the calculated reaction coordinate shown in Figure S2. Dihedral angle is defined as S1-S2-S3-S4.

Figure 12.

Overlay of the structure for the DMSOR TS (blue) using (CH3)3NO as substrate and the high-g split Mo(V) intermediate structure consistent with EPR, MCD, and electronic absorption spectra (red). The RMSD of first coordination sphere ligands is 0.19Å.

Calculations performed with DMSO as substrate show the presence of a second transition state and a corresponding Mo(IV) substrate bound intermediate, [Mo(dithiolene)2(OSer)(OS(CH3)2)]1−.15,30,31 The first transition state results from the association of substrate with square pyramidal 3, and the second transition state reflects the onset of the oxygen atom transfer step. These calculations have shown that the highest energy barrier along the reaction coordinate with DMSO as substrate is the oxygen atom transfer step. Since the N-O bond enthalpy of (CH3)3NO is less than that of the S-O bond in DMSO (ΔEbond ~16kcal/mol)63, the minimum on the potential energy surface for P-(CH3)3N should lie lower in energy than P-DMS, thereby lowering the second activation energy barrier for oxygen atom transfer. This is exactly what is observed in Figure 11, where the surface for P is stabilized such that there is no stable intermediate and the atom transfer step is activationless. Finally, the computational reaction profile mirrors what is observed in the enzyme reaction kinetics3 as well as what is observed in structurally characterized Mo model systems16 where no Mo(IV)-ON(CH3)3 substrate intermediate is observed under turnover or reaction conditions3.

CONCLUSIONS

A key Mo(V) intermediate in the catalytic cycle of DMSO has been trapped and examined in detail by EPR, electronic absorption, and MCD spectroscopies. Coupled with prior x-ray crystallographic data on DMSOR, the observation of a rhombic EPR spectrum provides clear evidence of a low-symmetry coordination geometry for this intermediate. The computed EPR spin-Hamiltonian parameters for a geometry-optimized computational model of the Mo(V) intermediate agree very well with those obtained from experiment. Taken together, the EPR data and calculations indicate an energetically stabilized coordination geometry for the Mo(V) intermediate that lies between idealized octahedral and trigonal prismatic. A configuration interaction model (SORCI) has been used to understand the electronic origin of the MCD and electronic absorption transitions in this intermediate. These CI calculations have very accurately reproduced the basic nature of the experimental C-term bandshape and the experimental oscillator strengths, allowing for a comprehensive assignment of both the MCD and electronic absorption bands. The same relaxed geometry computational model that was used in the analysis of the EPR data were also used to model the MCD and electronic absorption bandshapes, transition energies, and intensities. The fact that this Mo(V) intermediate possesses an energetically relaxed geometry is fully consistent with earlier enzyme kinetic studies that showed this intermediate builds up to ~100% under steady-state conditions with (CH3)3NO as substrate,3 and to a lesser degree with the substrate DMSO. Therefore, we attribute the rate-limiting nature of the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) reduction step during turnover to a relaxed geometry and a concommitant energetic stabilization of IMo(V) relative to the Mo(IV) state. The analysis of the MCD and electronic absorption spectra also revealed a low degree of Mo-Sdithiolene covalency in the redox orbital. This has the effect of reducing the electronic coupling which may contribute to the slow kinetics of the Mo(V)→Mo(IV) reduction step. Finally, calculations suggest that the reaction coordinate for DMSOR with (CH3)3NO as substrate possesses only a single transition state that arises from nascent Mo-O bond formation between the (CH3)3NO substrate oxygen atom and the previously 5-coordinate activated Mo(IV) center. The geometry of this transition state is remarkably similar to the relaxed Mo(V) geometry of IMo(V) that is consistent with the spectroscopic data, and this underscores the remarkable reactivity differences and relative stabilities of Mo(IV) and Mo(V) des-oxo six-coordinate sites at near geometric parity. Finally, our studies indicate that with the substrate (CH3)3NO energetic stabilization of the product potential energy surface renders the atom transfer event activationless. This results in the absence of a stable Mo(IV)-substrate bound intermediate with (CH3)3NO which is an observation that is entirely consistent with previous enzyme kinetic studies.3

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M.L.K. acknowledges the National Institutes of Health grant GM 057378 for financial assistance; R.H. acknowledges National Institutes of Health grant ES 012658 for financial assistance.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE Figure S1: Full active space orbitals used in SORCI calculations of the electronic absorption and MCD spectra for 1. Figure S2: Calculated reaction coordinate for DMSOR with TMAO as substrate showing the TS and the I-P intersection. Figure S3: C-term intensity for DMSOR intermediate at 5K and 7T. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- (1).Hille R. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2757. doi: 10.1021/cr950061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hille R. Molybdenum enzymes containing the pyranopterin cofactor: An overview. Vol. 39. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cobb N, Conrads T, Hille R. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Enemark JH, Cosper MM. Molybdenum and Tungsten:Their Roles in Biological Processes. 2002;39:621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Stewart L, Bailey S, Bennett B, Charnock J, Garner C, McAlpine A. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;299:593. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Garton SD, Temple CA, Dhawan IK, Barber MJ, Rajagopalan KV, Johnson MK. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:6798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Johnson MK, Garton SD, Oku H. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997;2:797. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Garton SD, Hilton J, Oku H, Crouse BR, Rajagopalan KV, Johnson MK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12906. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gruber S, Kilpatrick L, Bastian NR, Rajagopalan KV, Spiro TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8179. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kilpatrick L, Rajagopalan KV, Hilton J, Bastian NR, Stiefel EI, Pilato RS, Spiro TG. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3032. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rajagopalan KV. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997;2:786. [Google Scholar]

- (12).George GN. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997;2:790. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Baugh PE, Garner CD, Charnock JM, Collison D, Davies ES, McAlpine AS, Bailey S, Lane I, Hanson GR, McEwan AG. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1997;2:634. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Drew SC, Hill JP, Lane I, Hanson GR, Gable RW, Young CG. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:2373. doi: 10.1021/ic060585j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Tenderholt AL, Wang JJ, Szilagyi RK, Holm RH, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132:8359. doi: 10.1021/ja910369c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sugimoto H, Tatemoto S, Suyama K, Miyake H, Mtei RP, Itoh S, Kirk ML. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5368. doi: 10.1021/ic100825x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bray R, Adams B, Smith A, Richards R, Lowe D, Bailey S. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9810. doi: 10.1021/bi010559r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Joshi HK, Enemark JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11784. doi: 10.1021/ja046465x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kirk ML, McNaughton RL, Helton ME. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Vol. 52. 2004. p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Inscore FE, Knottenbelt SZ, Rubie ND, Joshi HK, Kirk ML, Enemark JH. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:967. doi: 10.1021/ic0506815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Inscore FE, McNaughton R, Westcott BL, Helton ME, Jones R, Dhawan IK, Enemark JH, Kirk ML. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1401. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Burgmayer SJN, editor. Dithiolenes in Biology. Vol. 52. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (23).McNaughton RL, Lim BS, Knottenbelt SZ, Holm RH, Kirk ML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4628. doi: 10.1021/ja074691b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Davie SR, Rubie ND, Hammes BS, Carrano CJ, Kirk ML, Basu P. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:2632. doi: 10.1021/ic0012017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).McMaster J, Tunney JM, Garner CD. Chemical Analogues of the Catalytic Centers of Molybdenum and Tungsten Dithiolene-Containing Enzymes. Vol. 52. John Wiley and Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Donahue JP, Goldsmith CR, Nadiminti U, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12869. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lim BS, Donahue JP, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:263. doi: 10.1021/ic9908672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lim BS, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1920. doi: 10.1021/ja003546u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Thapper A, Deeth RJ, Nordlander E. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:6695. doi: 10.1021/ic020385h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Thomson LM, Hall MB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3995. doi: 10.1021/ja003258y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Webster CE, Hall MB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5820. doi: 10.1021/ja0156486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Gibson JL, Falcone DL, Tabita FR. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:14646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bray R, Adams B, Smith A, Bennett B, Bailey S. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11258. doi: 10.1021/bi0000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).McWhirter RB, Hille R. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:23724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Stoll S, Schweiger A. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;178:42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Neese F. ORCA, an ab initio, density functional, and semi-empirical program package. University of Bonn; Germany: [Google Scholar]

- (37).SCM . Theoretical Chemistry. Vrije Universiteit; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: ADF2009.01. http://www.scm.com. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gaussian 03. R. C. G., Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Becke A. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Molecular orbitals were analyzed using the AOMix program [a, b]. Gorelsky SI. AOMix: Program for Molecular Orbital Analysis. York University; Toronto: 1997. http://www.sh-chem.net/ Gorelsky SI, Lever ABP. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001;635:187–196.

- (41).van Lenthe E, van der Avoird A, Wormer PES. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:4783. [Google Scholar]

- (42).vanLenthe E, Wormer PES, vanderAvoird A. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;107:2488. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;115:11080. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;119:9428. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:3939. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Seth M, Ziegler T. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:1793. doi: 10.1021/ic801802v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1994;101:9783. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Glendening ED, J., Badenhoop K, Reed AE, Carpenter JE, Bohmann JA, Morales CM, Weinhold F. 5.0 ed Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin; Madison: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Schafer A, Huber C, Ahlrichs R. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1994;100:5829. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. Journal of Molecular Graphics. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Stone J. An Efficient Library for Parallel Ray Tracing and Animation. 1998.

- (52).Solomon EI. In: Comm. Inorg. Chem. Sutin N, editor. Vol. 3. Gordon and Breach; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Bennett B, Benson N, McEwan AG, Bray RC. Euro. J. Biochem. 1994;225:321. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).George GN, Hilton J, Temple C, Prince RC, Rajagopalan KV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1256. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Mabbs FE, Collison D. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of d Transition Metal Compounds. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Finnegan MG, Hilton J, Rajagopalan KV, Johnson MK. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:2616. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Piepho SB, Schatz PN. Group Theory in Spectroscopy with Applications to Magnetic Circular Dichroism. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Neese F, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1847. doi: 10.1021/ic981264d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Kirk ML, Peariso K. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2003;7:220. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Avoird A, Ros P. Theoret. Chim. Acta (Berlin) 1966;4:13. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Benson N, Farrar JA, McEwan AG, Thomson AJ. FEBS Lett. 1992;307:169. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80760-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Hernandez-Marin E, Seth M, Ziegler T. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:1566. doi: 10.1021/ic901888q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lee SC, Holm RH. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2008;361:1166. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.