Abstract

Antibodies against the wheat storage globulin Glo-3A from a patient with both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and celiac disease were enriched to identify potential molecular mimicry between wheat antigens and T1D target tissues. Recombinant Glo-3A was used to enrich anti-Glo-3A immunoglobulin G antibodies from plasma by batch affinity chromatography. Rat jejunum and pancreas, as well as human duodenum and monocytes were probed, and binding was evaluated by immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. Glo-3A-enriched antibodies bound to a specific subset of cells in the lamina propria of rat jejunum that co-localized mostly with a marker of resident, alternatively activated CD163-positive (CD163+) macrophages. Blood monocytes and macrophage-like cells in human duodenum were also labelled with the enriched antibodies. Blocking studies revealed that binding to CD163+ macrophages was not due to cross-reactivity with anti-Glo-3A antibodies, but rather to non-Glo-3A antibodies co-purified during antibody enrichment. The novel finding of putative autoantibodies against tolerogenic intestinal CD163+ macrophages suggests that regulatory macrophages were targeted in this patient with celiac disease and T1D.

Keywords: Autoantibodies, CD163, Celiac disease, Gut, Glo-3A, Macrophages, Mimicry, Type 1 diabetes

Abstract

Les anticorps contre la globuline de réserve du blé Glo-3A d’un patient atteint à la fois de diabète de type 1 (DT1) et de maladie cœliaque ont été enrichis pour repérer l’imitation moléculaire potentielle entre les antigènes du blé et les tissus cibles du DT1. La Glo-3A recombinante a été utilisée pour enrichir les anticorps d’immunoglobulines G anti-Glo-3A du plasma par chromatographie d’affinité par lots. Les chercheurs ont sondé le jéjunum et le pancréas de rats, de même que le duodénum et les monocytes d’humains, et ont évalué la liaison par immunohistochimie et microscopie confocale. Les anticorps enrichis de Glo-3A se fixent à un sous-groupe précis de cellules de la lamina propria du jéjunum de rats qui se colocalisent surtout avec un marqueur de macrophages positifs au CD163 (CD163+) résidents, subsidiairement activé. Les monocytes sanguins et les cellules semblables aux macrophages dans le duodénum d’humains ont également été étiquetés par les anticorps enrichis. Des études de blocage ont révélé que la liaison aux macrophages CD163+ n’était pas causée par une transréactivité aux anti-corps anti-Glo-3A, mais plutôt aux anticorps non-Glo-3A copurifiés pendant l’enrichissement des anticorps. Cette nouvelle observation d’auto-anticorps présumés contre les macrophages CD163+ intestinaux tolérogènes laissen supposer que des macrophages de régulation ont été ciblés chez ce patient atteint de maladie cœliaque et de DT1.

Defective intestinal immunity can lead to impaired oral tolerance, chronic inflammation and gut leakiness. These conditions have been reported to precede the development of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in diabetes-prone BioBreeding (BBdp) rats and humans (1). We previously described a case involving a patient with both T1D and celiac disease who displayed strong antibody and T cell reactivity to wheat peptides, including those from the diabetes-related wheat storage globulin homologue of Glb1 (2) now known as Glo-3A (3). Additional studies revealed abnormal immune reactivity to Glo-3A in a subset of children at high risk for T1D (4) and in young children with celiac auto-immunity (5). To investigate mechanisms by which the immune response elicited by this dietary protein could contribute to inflammation in the gut or pancreas, and possibly T1D development, we probed target tissues with Glo-3A-enriched antibodies from the aforementioned patient to identify potential molecular mimicry.

METHODS

The clinical characteristics of the index patient with both T1D and celiac disease were described previously (2). Briefly, a young woman with a 10-year history of T1D and positive for tissue transglutaminase antibody was adhering to a standard gluten-free diet when she presented with diarrhea, oral ulcerations and severe swelling of the lips. The patient displayed strong T cell proliferative responses to wheat peptides including Glo-3A (2). Only the initiation of a strict, specified carbohydrate, cereal-free diet resolved the diarrhea and resulted in the healing of her mouth ulcerations. Plasma was prepared and frozen for future analyses. Informed consent was obtained and the study was approved by the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board (Ottawa, Ontario).

To purify Glo-3A antibodies from this patient, recombinant Glo-3A protein was prepared. A His-Glo-3A DNA fragment was excised from the pET17b-His-Glo-3A vector using XbaI and Xho1 restriction enzymes (Invitrogen, USA) and cloned into the XbaI/XhoI restriction enzyme sites of the pBacPak9 transfer vector (Clontech Laboratories, USA). The tagged gene was integrated into BacPAK6 viral DNA using Bacfectin (Clontech Laboratories, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For protein expression and purification of His-Glo-3A, SF21 insect cells were infected with recombinant BakPAK6-His-Glo-3A virus. Recombinant His-Glo-3A was purified using Ni-NTA agarose according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To enrich human Glo-3A antibodies using batch affinity chromatography, 500 mg of lyophilized cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose-4B (GE Healthcare, USA) were resuspended and coupled to 5 mg of recombinant Glo-3A. Excess ligand was removed by a series of washes with coupling buffer. After inactivation of the remaining active sites on the sepharose beads, the rGlo-3A-coupled medium was subjected to three cycles of low and high pH washes. Two millilitres of plasma diluted 1:2 in phosphate-buffered saline was incubated with 150 μL of rGlo-3A-coupled medium with end-over-end rotation overnight at 4°C. Bound antitotal immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies were eluted and the presence of Glo-3A IgG antibodies was confirmed by ELISA and Western blotting.

Human monocytes were isolated from the blood of one control subject (25-year-old Caucasian man) using density gradient centrifugation over Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and the EasySep Negative Selection Human Monocyte Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, USA). The enriched monocytes were more than 80% pure as determined by flow cytometry analysis using the macrophage/ monocyte marker CD14 (data not shown). The monocyte pellet was fixed in Bouin’s fixative and embedded in paraffin.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (6). For avidin-biotin peroxidase staining, Glo-3A-enriched antibodies (diluted 1:200 for rat sections and 1:50 for human sections) and biotinylated anti-human IgG (1:300) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used. For immunofluorescence staining, Glo-3A-enriched antibodies (1:50) and goat anti-rat CD163 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, USA) (1:50) were used as primary antibodies. Donkey anti-goat/Alexa 488 (1:400) (Invitrogen, USA) was applied, followed by biotinylated anti-human IgG (1:300) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and streptavidin/Cy3 (1:600). Co-localization of cells labelled with Glo-3A-enriched antibodies and anti-CD163 antibodies was analyzed using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, USA) (6). To evaluate whether binding was Glo-3A specific, 200 μg/mL of either rGlo-3A or insect cell proteins (without rGlo-3A) were added to the Glo-3A-enriched antibody preparation.

RESULTS

Antibody reactivity to rat CD163+ intestinal macrophages, human intestinal macrophage-like cells and a subset of human peripheral monocytes

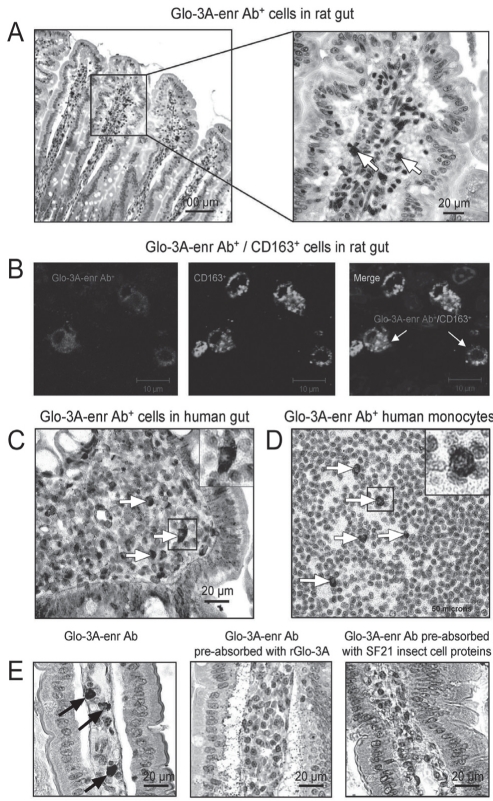

Pancreatic and jejunal sections from a 45-day-old BBdp rat were probed with Glo-3A-enriched antibodies. There was strong staining of a specific population of macrophage-like cells in the lamina propria of the small intestinal villi (Figure 1A). These antibodies also bound to lamina propria cells in control BB and Wistar Furth rat small intestine. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that most of the cells labelled with the enriched anti-Glo-3A antibodies (Cy3) co-localized with a subset of macrophages expressing CD163 (Alexa 488) (Figure 1B). No labelling was observed in non-inflamed pancreas (data not shown). Staining of human duodenal sections with the Glo-3A-enriched antibodies revealed a similar labelling of macrophage-like cells in the lamina propria (Figure 1C). Staining of human peripheral blood monocytes revealed a subset of cells that was labelled with the Glo-3A-enriched antibodies (Figure 1D).

Figure 1).

CD163-positive (CD163+) intestinal macrophage-specific antibodies (Ab) in the plasma of a patient with both type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. A Labelling of 45-day-old BioBreeding (BBdp) rat jejunum sections with Glo-3A-enriched Ab (Glo-3A-enr Ab) (1:200 dilution). B Double immunofluorescence labelling of BBdp rat jejunum sections with Glo-3A-enr Ab (1:50 dilution) and anti-CD163 Ab (1:50 dilution). Confocal microscopy revealed that cells labelled with the Glo-3A-enr Ab predominantly co-localized with cells expressing CD163 (a marker for anti-inflammatory, tissue-resident macrophages). C Macrophage-like cells in human duodenal sections were labelled by Glo-3A-enr Ab (arrows). D Glo-3A-enr Ab reacted with a subset of human peripheral blood monocytes (arrows). E Labelling of intestinal macrophages in BBdp rat jejunum sections with Glo-3A-enr Ab (1:25 dilution) was blocked by pre-absorption with recombinant Glo-3A (200 μg/mL) and SF21 insect cell proteins without rGlo-3A (200 μg/mL) (arrows). Because insect cell proteins block only non-Glo-3A Ab, this further suggests the presence of non-Glo-3A Ab capable of binding macrophages in this patient. Ab+ refers to cells bound by antibody

To further confirm the specificity of anti-Glo-3A antibody cross-reactivity in the gut, a series of control blocking experiments was performed with recombinant Glo-3A and SF21 insect cell proteins (without recombinant Glo-3A). The labelling was blocked by pre-absorption with either recombinant Glo-3A or with SF21 insect cell proteins (Figure 1E). Similarly, labelling of human monocytes was blocked by pre-absorption with either recombinant Glo-3A or with SF21 insect cell proteins (data not shown). Because Glo-3A was prepared in insect cells, Western blots of rGlo-3A were probed with the enriched antibody preparation pre-absorbed with rGlo-3A (prepared in insect cells) or insect cell proteins alone (data not shown). The present study revealed that Glo-3A antibodies were specifically blocked only by the rGlo-3A preparation, and not blocked by insect cell proteins alone. Thus, pre-absorption with insect cell proteins blocks only non-Glo-3A antibodies that bound to gut tissue. These experiments revealed that antibody reactivity to intestinal macrophages was not due to specific cross-reactivity with human anti-Glo-3A antibodies, but rather to non-anti-Glo-3A antibodies that were co-purified during the enrichment process.

DISCUSSION

The original objective was to study whether Glo-3A antibodies could bind structures in the gut or pancreas consistent with the concept of molecular mimicry. Antibodies from a Glo-3A-enriched preparation labelled a subset of CD163-positive (CD163+) macrophages in rat jejunum lamina propria, a subset of human peripheral monocytes and macrophage-like cells in human duodenum. However, further control antibody-blocking experiments demonstrated that labelling was not due to anti-Glo-3A antibodies. Therefore, these results do not support molecular mimicry as an explanation for the enriched Glo-3A antibody cross-reactivity to macrophages. The serendipitous discovery of putative auto-antibodies against small intestinal macrophages in a patient with both T1D and celiac disease is an intriguing finding, suggesting the potential involvement of resident CD163+ macrophages in the pathophysiology of one or both of these diseases. CD163 is a class B scavenger receptor for hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes that are expressed exclusively on monocytes and macrophages. CD163+ macrophages are mature, tissue-resident macrophages present at high frequency in the gastrointestinal tract of rats. They are associated with homeostatic functions including the suppression and resolution of inflammation, and wound healing (7). Unfortunately, the limited volume of patient plasma made it difficult to identify specific macrophage molecules targeted by these autoantibodies.

To our knowledge, autoantibodies against macrophages have not been described in patients with T1D or celiac disease. However, such antibodies have been described in systemic lupus erythematosus, in which auto-antibodies against the class A scavenger receptors on macrophages of the marginal zone of the spleen were identified (8). A recent analysis of T1D HLA susceptibility gene interactions with candidate proteins (9) identified macrophage scavenger receptor class A as part of the consensus interactome network related to the T1D risk gene HLA-DR3. Furthermore, deficiencies in the clearance of apoptotic cells (including pancreatic beta cells) by macrophages have been described in diabetes-prone rats and mice, and there are fewer CD163+ (ED2+) macrophages in BBdp rats compared with controls (10). Our initial investigations revealed significantly reduced numbers of CD163+ macrophages in the small intestine of diabetes-prone animals compared with controls (unpublished data).

Tripathi et al (11) identified human zonulin – a key regulator of tight junctions in the intestinal epithelium – as prehaptoglobin-2. Prehaptoglobin-2 is a known precursor of haptoglobin and, similar to haptoglobin, contains a CD163 binding site, further suggesting the importance of CD163+ macrophages in the modulation of intestinal immunity and, possibly, gut permeability. The identification of putative auto-antibodies against this macrophage population suggests a mechanism by which the normal homeostatic functions of these innate immune cells in the gut could be compromised. There is one report that diabetic patients harboured approximately 50% fewer CD163+ blood monocytes than age-matched controls (12). Taken together, these data raise the novel possibility that a deficit in tolerogenic CD163+ cells is implicated in the chronic intestinal inflammation and loss of oral tolerance observed in some T1D and celiac disease patients. CD163 could be a disease marker and a therapeutic target.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the volunteers and to Drs Claire Touchie and Jacob Karsh (The Ottawa Hospital).

Footnotes

SUPPORT: This study was funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. BS received a scholarship from Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and BS, CP and AJM received funding from Ontario Graduate Scholarships. AS was supported by a PDF Fellowship from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (3-2007-755).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sonier B, Patrick C, Ajjikuttira P, Scott FW. Intestinal immune regulation as a potential diet-modifiable feature of gut inflammation and autoimmunity. Int Rev Immunol. 2009;28:414–45. doi: 10.3109/08830180903208329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mojibian M, Chakir H, MacFarlane AJ, et al. Immune reactivity to a glb1 homologue in a highly wheat-sensitive patient with type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1108–10. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loit E, Melnyk CW, MacFarlane AJ, Scott FW, Altosaar I. Identification of three wheat globulin genes by screening a Triticum aestivum BAC genomic library with cDNA from a diabetes-associated globulin. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson M, Mojibian M, Barriga K, et al. An exploration of Glo-3A antibody levels in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:563–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taplin C, Mojibian M, Simpson M, et al. Antibodies to the wheat storage globulin Glo-3A in children before and at diagnosis of celiac disease. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:21–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f18c7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang GS, Kauri LM, Patrick C, Bareggi M, Rosenberg L, Scott FW. Enhanced islet expansion by beta-cell proliferation in young diabetes-prone rats fed a protective diet. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:501–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Gorp H, Delputte PL, Nauwynck HJ. Scavenger receptor CD163, a Jack-of-all-trades and potential target for cell-directed therapy. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:1650–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wermeling F, Chen Y, Pikkarainen T, et al. Class A scavenger receptors regulate tolerance against apoptotic cells, and autoantibodies against these receptors are predictive of systemic lupus. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2259–65. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brorsson C, Tue Hansen N, Bergholdt R, Brunak S, Pociot F. The type 1 diabetes-HLA susceptibility interactome – identification of HLA genotype-specific disease genes for type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen RE, Talarico G, Noble B. Phenotypic characterization of mononuclear inflammatory cells in salivary glands of bio-breeding rats. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42:649–55. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906773106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asleh R, Marsh S, Shilkrut M, et al. Genetically determined heterogeneity in hemoglobin scavenging and susceptibility to diabetic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2003;92:1193–200. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000076889.23082.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]