Abstract

Legislation that supports the establishment of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) was recently enacted into law as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and in 2012 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin contracting with ACOs. Although ACOs will play a significant role in reform of the U.S. health care delivery system, thus far, discussions have focused exclusively on the coordination of conventional health services. This article discusses the potential engagement of the complementary and alternative (CAM) workforce in ACOs and the foreseeable impacts of ACO legislation on the future of U.S. CAM services.

Introduction

One of the fundamental problems of the current U.S. health care system is that practitioners lack responsibility for population health outcomes and health care spending. The need to design a health care delivery system that encourages practitioner accountability1 is now well recognized among policymakers, payers, and other stakeholders. Conceptually, a health care delivery system that promotes practitioner accountability is promising2,3; however, the “how to” of designing accountable care systems is seemingly complex, and the image of what accountable care may look like continues to evolve as discussions unfold.

The extreme diversity of health care systems, stakeholders, and health care needs across the United States only adds to the confusion of how to best design accountable care systems. It is becoming evident that the practitioner partnerships that comprise Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) will likely vary considerably from region to region.4,5 ACO participants will share incentives to improve health care quality and population health while controlling health care spending.1 Despite uncertainty as to how ACOs will work, who will be involved, and exactly how payment incentives will be structured, health care reform legislation enacted last March as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act supports ACOs and, in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will start contracting with them. Beginning with payment reform for Medicare, ACOs will likely shape the way other health care insurances operate.

Previous discussions regarding ACOs have focused exclusively on conventional health services. As ACOs begin to take form, there will need to be serious consideration regarding which ancillary health services to include or exclude. As a result of strong public demand, there remains a relatively large and ready U.S. workforce of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners that could potentially assist ACOs in achieving their specific primary care aims.

In this article, the potential involvement of CAM practitioners in ACOs will be explored. This is a critical time for the U.S. health care system, and, as discussed herein, an important time for CAM professions to consider how they might fit into an ACO era.

The Supply and Demand of Common CAM Services in the United States

Now that it has been nearly 2 decades since the seminal studies on U.S. CAM were published,6,7 CAM services have fallen off the radar among many health services researchers, policymakers, and payers who were initially interested in CAM. Nevertheless, recent surveys continue to demonstrate the substantial demand for CAM services,8,9 and consequent to this demand there continues to be a relatively large supply of U.S. CAM practitioners.10–13

Estimating the national supply and demand of CAM practitioner services is a challenge due to the extreme diversity among CAM providers and newly emerging modalities that make it difficult to consistently define what constitutes CAM. In addition, low barriers of entry into the workforce among some forms of CAM such as massage therapy make precise enumeration of CAM supply impossible. In the United States, the most common CAM practitioners are licensed acupuncturists/practitioners of Oriental medicine, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians.8 According to the authors' conservative estimates from 2006 and 2007 data sources, there are at least 180,600 CAM practitioners in the United States (approximately 8 CAM practitioners per 10,000 adult capita) (Table 1). Given that there are approximately 940,000 physicians (∼300,000 primary care physicians and ∼600,000 specialists), it suggests that the CAM workforce is relatively large in comparison.14 With the exception of naturopathy, most states now license CAM practitioners,12,13,15 and payment sources are provided by a mix of self-pay, private, and public payers (although most expenditures are out-of-pocket).16

Table 1.

National Supply and Demand of Common Complementary and Alternative Medicine Practitioner Services

| Total U.S. practitioners | Practitioners per 10,000 capitaa | No. of U.S. states that require licensure11,12,15 | Total U.S. adult users, millions (%)b | Total U.S. adult visits, millionsb | Total expenditures, billions (2008$)b | Payment sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acupuncture/Oriental medicine | 25,000+12 | 1.1 | 42 | 3.1 (1.4) | 7.7 | 0.8 | Most out-of-pocket, Medicaid (7+ states), & some private |

| Chiropractic care | 52,00011 | 2.3 | 50 | 12.0 (5.3) | 96.1 | 6.9 | Medicare, Medicaid (33+ states), & private |

| Massage therapy | 100,000+c | 4.4 | 43 | 18.1 (8.0) | 95.3 | 5.1 | Most out-of-pocket, some private |

| Naturopathy | 360,013 | 0.2 | 15 | 0.7 (0.3) | 3.2 | 0.3 | Most out-of-pocket, Medicaid (1+ states), & some private |

| Total | 180,600 | 8.0 | 202.3 | 14.2 |

Calculations based on estimated 227 million U.S. adults: U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact Finder. American Community Survey. Online document at: http://factfinder.census.gov/ Accessed October 5, 2010.

Calculations based on the authors' calculations from both the 2008 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (chiropractic care) and the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (out-of-pocket payment for acupuncture/Oriental medicine, massage, and naturopathy); 2007 data were converted to 2008 dollars using the consumer pricing index for professional medical services. U.S. Department of Labor. Consumer Price Index. Online document at: www.bls.gov/cpi

Estimate based on professional membership in The American Massage Therapy Association and The Association of Bodywork and Massage Professionals.20

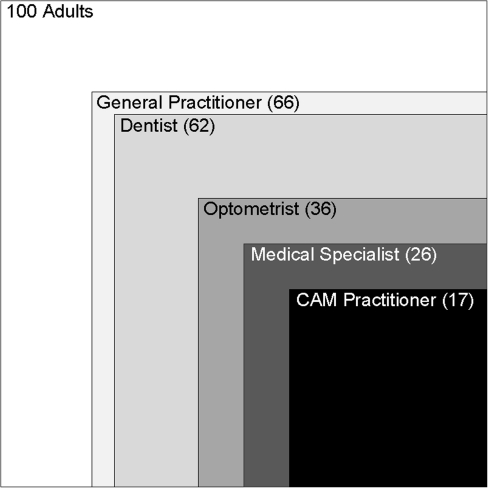

How consumers value different health services is reflected by utilization and expenditures, which in turn are affected by access to care. There continues to be strong support for CAM practitioner services when compared to other health services (Fig. 1). Our estimates generated from the 2007 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)17 and the National Health Interview Survey18 are that ∼20 million adults are regular users: 202 million visits are made annually to CAM practitioners at a cost of over $14 billion (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Self-reported health services use in previous 12 months per 100 U.S. adults according to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey.18 CAM, complementary and alternative medicine. Numbers represent the total number of adults out of 100 who reported consulting the provider-type in the previous year.

CAM Practitioners' Potential Involvement in ACOs

Whether or not medical practitioners, policymakers, and payers personally support CAM, its inclusion or exclusion from national health care reform efforts such as ACOs will have direct and indirect consequences.

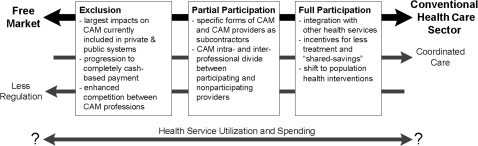

It is anticipated that CAM practitioners will be one of the following: (1) excluded practitioners, (2) partially participating subcontractors, or (3) fully participating practitioners and included as “shared-savings” constituents in ACOs (Fig. 2). The level of involvement will affect payment, professional regulation, care coordination, and health services utilization (Table 2). Exclusion of CAM services from ACOs would likely drive CAM entirely into a free market economy as future private health care reimbursement will be based on the ACO framework that will begin with Medicare reform. Conversely, if CAM practitioners become full participants, especially in light of the shared-savings incentives, CAM would become highly integrated with conventional health services.

FIG. 2.

Potential effects of exclusion, partial participation, and full participation of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners in Accountable Care Organizations.

Table 2.

Select Influential Complementary and Alternative Medicine Professional Organizations

| Organization | Website |

|---|---|

| Acupuncture/Oriental medicine | |

| American Association of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine | www.aaaomonline.org |

| National Acupuncture Foundation | www.nationalacupuncturefoundation.org |

| Chiropractic care | |

| American Chiropractic Association | www.acatoday.org |

| International Chiropractors Association | www.chiropractic.org |

| The World Federation of Chiropractic | www.wfc.org |

| Massage therapy | |

| American Massage Therapy Association | www.amtamassage.org |

| Associated Bodywork & Massage Professionals | www.abmp.com |

| Naturopathy | |

| American Association of Naturopathic Physicians | www.naturopathic.org/ |

| American Naturopathic Medical Association | www.anma.org/ |

| General complementary and alternative medicine/integrative medicine | |

| Integrated Healthcare Policy Consortium | www.ihpc.info/ |

| Academic Consortium for Complementary and Alternative Health Care | www.accahc.org/ |

| Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine | www.imconsortium.org/ |

| The Institute for Integrative Health | www.tiih.org/ |

There will likely be variation in the type of services selected for inclusion and exclusion among specific ACOs. Within the three possible levels of participation, the extent to which ACOs select CAM services will be dependent on the flexibility of federal policies. The future policies that dictate how ACOs will be structured and function are, according to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act legislation, left largely to the Department of Health and Human Services. The developing empirical evidence on both cost and efficacy of CAM from ongoing research activities funded primarily by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health will likely help inform which CAM services might be included in ACOs.

Impact on care coordination

Authorities have argued for the establishment of a strong primary care model such as the “patient-centered medical home” (PCMH) within ACOs.19 The PCMH would create a strong primary care system to help manage chronic disease and control costs, while ACOs might encourage providers to work more collaboratively across the continuum of patient care to improve population health and control costs. Exactly which providers are incentivized to collaborate appears to be up for debate.

Despite the alternative broad-based approaches to health that some forms of CAM take, the vast majority of CAM visits are for common musculoskeletal conditions such as neck and back pain,20,21 which perhaps not surprisingly are some of the most common conditions primary care providers see in their offices.22 And CAM patients don't typically inform their medical practitioners of their CAM use.6 Considering this overlap and lack of care coordination, inclusion of CAM providers in PMCH and ACO initiatives might both improve coordination and reduce service duplication, much more so than inclusion of other ancillary services such as dentistry and optometry, where overlap with traditional medical services is limited.

Impact on health services utilization and spending

In order to anticipate the effects of health care reform on health care consumer behavior, the perspective of the health care consumer needs to be considered.23 Beyond conforming to popular interests, the inclusion of CAM practitioners in ACOs has potential to impact utilization and spending on health services.

While the estimated $14 billion spent on CAM practitioner services may seem large, especially when we consider who will pay for CAM services in the future, it is a small fraction of total national health care spending. Interestingly, analyses of the inflation-adjusted amount spent per visit to CAM practitioners suggests that spending per visit on CAM does not appear to have changed over the last 10 years, unlike expenditures on medical services.24 This suggests that some CAM services are immune to rising health care costs, or it could also be argued that CAM operates in more of a free market than the conventional medical sector (because of less government influence, heightened competition between services, more entrepreneurial activity, and a greater proportion of cash payment). The price of CAM services may therefore be more balanced with what consumers are willing or able to pay, unlike medical services for which payment is through third-party intermediates. Interestingly, cash-based health services appear to have been more affected by the 2008–2009 U.S. economic recession.25 Complementary and alternative medicine services are typically less technology-based interventions that function in more of a self-regulating free market than the conventional health care sector.

Assuming relative stability in the number of visits per user, which would be more likely if CAM practitioners were part of the ACOs shared-savings payment system, CAM services could potentially help slow rising health care spending despite the initial upfront investment to cover the services. As ACO spending will be compared to benchmarks, inclusion of CAM providers might help control spending by being more resistant to cost increases per unit of care and potentially replacing more expensive interventions, thereby benefitting ACOs.

Conversely, given that most CAM users currently seek CAM to complement their medical care,26 making CAM more accessible by including CAM services in ACOs could also encourage more simultaneous health services use and increase spending further. However, it is difficult to forecast the short-term and long-term effects, as they are dependent on whether CAM services are used simultaneously, or in place of more costly medical care.

Exclusion of CAM from ACOs could have very different indirect effects. The establishment of ACOs will shift medical services away from a fee-for-service toward a population health model and employ incentives that discourage unnecessary testing and treatment. In the eyes of the health care consumer, this could be perceived as rationing care, and consequent help-seeking behaviors could paradoxically drive increased consumption of CAM practitioner services in a fee-for-service payment model. Such a scenario could indirectly raise health care costs and further fragment care.

Considerations and Challenges for Policymakers

If policymakers pursue integrating CAM services into ACOs, there exist a number of considerations and challenges. Many of these remain unanswered questions as most CAM research to date has focused on the mechanisms behind CAM rather than on health services delivery and integration. Among these, a few pertinent issues are highlighted that policymakers will need to consider.

Diversity of CAM practitioners

The overwhelming majority of CAM remains a “cottage industry” in the United States and, consequently, there exists considerable variation both within CAM professions and between CAM professions. The expansive diversity of CAM services may appeal to many different personal and health belief systems, yet it creates a substantial barrier to integrating CAM practitioner services with predominately medical initiatives such as ACOs. Certain CAM practitioners and services will likely be more suited to provide services within the ACO framework than others. While there may be no formal way to identify CAM practitioners more likely to integrate well with medical practitioners in ACOs, providing reimbursement flexibility to encourage ACOs to experiment with CAM providers may be beneficial. In many ways, a medical-CAM ACO that collectively shares savings would be self-regulating, as the shared goal would incentivize collaboration and a mutual thirst for uncovering cost-effective and efficient care pathways.

Who provides CAM best?

A significant barrier to integration of CAM services is that the lines that differentiate modalities do not necessarily coincide with professions. Over the last 2 decades, there has been growing interest in CAM among medical students27–29 and, consequently, a growing number of medical practitioners provide CAM.30 Whether to engage a CAM practitioner or offer a CAM service provided by a medical practitioner in an ACO will need consideration. From a population health perspective, the most obvious solution is to include the practitioner that providers the CAM service most effectively, efficiently, and safely. However, there are few empirical studies that compare relative effectiveness, efficiency, and safety of CAM modalities provided by different practitioner types.

CAM as primary versus specialty care

On one level, given the “whole person” approach adopted by many CAM professions and the considerable overlap in conditions commonly treated by CAM practitioners and primary care providers, CAM may fit squarely into primary care. Nevertheless, among the forms of CAM currently reimbursable by private and public payers such as chiropractic care, these services are viewed as specialty care. As CAM professions become involved in the ongoing health care reform debate, deciding whether specific CAM services have any role in primary care such as PCMH or are more congruent as specialists in the broader ACO will be a challenge.

Considering that musculoskeletal conditions are the most common conditions treated by both CAM practitioners and primary care providers,21,22 CAM providers could play a potential role in primary care offices and help relieve the primary care workload. The authors believe there is a need for research regarding the integration of CAM providers into primary care settings such as PCMHs and clinical microsystems.31,32

Luxury versus necessity care

Reasons for CAM use may vary, but generally CAM is used to complement medical care for either general health or as a modality to treat a specific illness.26,33 Interestingly, a recent qualitative study found that CAM users view CAM either as a form of treatment for a health condition or as a luxury service.34 Unless long-term benefits of CAM use for general health are proven empirically, CAM use for general health in ACOs will be controversial. Cash-based payment for use of CAM as a luxury service is most appropriate; however, to the degree CAM modalities can be demonstrated to be effective at promoting health, they might be considered to be private and public reimbursable services. Should CAM practitioner services become involved in ACOs, monitoring appropriate use will likely be a considerable challenge, but may bring more discipline and science to the CAM field.

A Call for Collaboration Across Complementary and Alternative Professions

As policymakers, payers, and stakeholders come together to discuss ACOs, the authors believe CAM professions will have a louder voice as one large group. There are a diverse number of professional organizations both within and across CAM professions (Table 2) that united could influence adoption of CAM into national health care reform efforts such as ACOs. Conversely, should CAM professional organizations continue to act individually, increased competition between CAM professions might preclude their participation in reform efforts.

The U.S. health care system is now positioned for substantial change; at the center of reform is a health care delivery system that promotes practitioner accountability for population health outcomes, care coordination, and the control of health care spending. Considering the strong demand for CAM and the relatively large CAM workforce, CAM practitioners could become active participants in ACOs, especially if professional organizations combine efforts. Although there is considerable uncertainty pertaining to the design of ACOs, who will be involved, and which services will be included, should CAM practitioners and professions fail to get involved in the discussion now, they may not have the opportunity later.

Acknowledgments

M.A.D. and W.B.W. were supported by Award Number 1K01AT006162 from the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. J.M.W. was supported by Award Number 5K01AT005092 from the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Shortell SM. Casalino LP. Health care reform requires accountable care systems. JAMA. 2008;300:95–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher ES. McClellan MB. Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: Moving forward in medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w219–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClellan M. McKethan AN. Lewis JL, et al. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:982–990. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KD. Coddington DC. Accountable care the journey begins. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shortell SM. Casalino LP. Fisher ES. How the center for Medicare and Medicaid innovation should test accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1293–1298. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg DM. Davis RB. Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg DM. Kessler RC. Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States: Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes PM. Bloom B. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;10:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes PM. Powell-Griner E. McFann K. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;27:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldert D. Martinez D. The supply of naturopathic physicians in the United States and Canada continues to increase. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2006;11:120–122. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MA. Davis AM. Luan J. Weeks WB. The supply and demand of chiropractors in the United States from 1996 to 2005. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009;15:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Acupuncture Foundation: Chronology of First Acupuncture Practice Laws & Reported Number of Licensees in Each State. www.nationalacupuncturefoundation.org/pages/publications.html. [Oct 27;2010 ]. www.nationalacupuncturefoundation.org/pages/publications.html

- 13.American Association of Naturopathic Physicians. Licensed States and Licensing Authorities. www.naturopathic.org/content.asp?contentid=57. [Oct 27;2010 ]. www.naturopathic.org/content.asp?contentid=57

- 14.Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 2010. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg DM. Cohen MH. Hrbek A, et al. Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:965–973. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahin RL. Barnes PM. Stussman BJ. Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;18:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Household Component Full Year Files. 2007. www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp. [Mar 5;2011 ]. www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_files.jsp

- 18.National Health Interview Survey, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. [Mar 5;2011 ]. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm

- 19.Rittenhouse DR. Shortell SM. Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care: Two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2301–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherkin DC. Deyo RA. Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:378–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cherkin DC. Deyo RA. Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Family Med. 2002;15:463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deyo RA. Phillips WR. Low back pain: A primary care challenge. Spine. 1996;21:2826–2832. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199612150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bechtel C. Ness DL. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:914–920. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis MA. Sirovich BE. Weeks WB. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:748–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin A. Lassman D. Whittle L. Catlin A. Recession contributes to slowest annual rate of increase in health spending in five decades. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:11–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elder W. Rakel D. Heitkemper M, et al. Using complementary and alternative medicine curricular elements to foster medical student self-awareness. Acad Med. 2007;82:951–955. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318149e411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus DM. McCullough L. An evaluation of the evidence in “evidence-based” integrative medicine programs. Acad Med. 2009;84:1229–1234. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b185f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stratton TD. Benn RK. Lie DA, et al. Evaluating CAM education in health professions programs. Acad Med. 2007;82:956–961. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31814a5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diehl DL. Kaplan G. Coulter I, et al. Use of acupuncture by American physicians. J Altern Complement Med. 1997;3:119–126. doi: 10.1089/acm.1997.3.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson EC. Godfrey MM. Batalden PB, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 1: The building blocks of health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:367–378. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasson JH. Anders SG. Moore LG, et al. Clinical microsystems, part 2: Learning from micro practices about providing patients the care they want and need. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis MA. West AN. Weeks WB. Sirovich BE. Health behaviors and utilization among users of complementary and alternative medicine for treatment versus health promotion. Health Serv Res. 2011 May 10; doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01270.x. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop FL. Yardley L. Lewith GT. Treat or treatment: A qualitative study analyzing patients' use of complementary and alternative medicine. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1700–1705. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]