Abstract

This study investigated the augmentation of endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) thromboresistance by using gene therapy to overexpress thrombomodulin (TM), an endothelial cell membrane glycoprotein that has potent anti-coagulant properties. Late outgrowth EPCs were isolated from peripheral blood of patients with documented coronary artery disease and transfected with an adenoviral vector containing human TM. EPC transfection conditions for maximizing TM expression, transfection efficiency, and cell viability were employed. TM-overexpressing EPCs had a fivefold increase in the rate of activated protein C production over native EPCs and EPCs transfected with an adenoviral control vector expressing β-galactosidase (p<0.05). TM upregulation caused a significant threefold reduction in platelet adhesion compared to native EPCs, and a 12-fold reduction compared to collagen I-coated wells. Additionally, the clotting time of TM-transfected EPCs incubated with whole blood was significantly extended by 19% over native cells (p<0.05). These data indicate that TM-overexpression has the potential to improve the antithrombotic performance of patient-derived EPCs for endothelialization applications.

Introduction

Endothelial cells (ECs) make up the inner lining of all natural blood vessels and perform critical functions in thromboregulation and mediation of vascular health. The seeding of ECs onto the blood-contacting surface of synthetic materials has been shown to improve the performance of biomedical implants such as synthetic vascular grafts,1 vascular assist devices,2 and heart valves.3 Effective endothelialization of the material surface requires that a fully confluent monolayer of ECs remain adherent and express a healthy, quiescent EC phenotype.4 A subconfluent monolayer of ECs can lead to a thrombogenic surface,5 whereas injured or activated adherent ECs expose tissue factor and down regulate key antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory molecules,6,7 increasing the risk of thrombosis and intimal hyperplasia due to smooth muscle cell activation.

We and others have shown that rare peripheral blood-derived EC-like cells, termed late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells or endothelial colony forming cells, can be isolated from patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).8,9 In this study EC-like late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells are simply referred to as “EPCs.”

The isolation of EPCs from peripheral blood, a method less invasive than surgical harvest of ECs from large veins or adipose tissue, is a significant development for autologous endothelialization of vascular grafts.10–12 EPCs can be expanded to higher densities with minimal contamination with other cell types, maintain firm adhesion to the underlying substrate, and can express a healthy quiescent EC phenotype in vitro.8 EPCs have been shown to mediate clot formation, releasing antithrombotic molecules to prevent platelet activation and reduce thrombus formation.13,14 Proof-of-principle studies have shown that animal-derived EPCs can improve the patency rates of synthetic small-diameter vascular grafts.15–17 While harvesting EPCs from CAD patients is attractive, there is concern that both CAD and aging may lead to decreased functional activity of these cells18 and detract from a healthy antithrombogenic phenotype.19,20

Thrombomodulin (TM) is an endogenous antithrombotic molecule expressed at the surface of ECs that plays a key role in mediating endothelial thromboresistance. TM acts in two manners: first by scavenging excess thrombin, and second by accelerating the production of activated protein C (APC). Inhibiting thrombin activity reduces fibrin formation and the activation of platelets, leukocytes, and smooth muscle cells,21 whereas increased APC production acts upstream and limits thrombin generation,22 reduces the expression of inflammatory cytokines,23–25 down regulates EC expression of adhesion molecules to prevent leukocyte adhesion,26 and inhibits EC apoptosis.27

Because TM is decreased in patients with diabetes and atherosclerosis28,29 we hypothesized that overexpression of TM by patient-derived EPCs would enhance their performance for vascular graft endothelialization protocols. The inhibition of thrombin activity through TM overexpression may reduce the number of thrombosis-caused failure events occurring in vascular constructs within the first week postimplant while also reducing inflammation and the progression of atherosclerosis.30,31 The objective of the current study was to assess in vitro the feasibility of augmenting the expression of TM in patient-derived EPCs to create a short-lived enhancement of the intrinsically antithrombotic phenotype of healthy ECs. EPCs isolated from patients with documented CAD were transfected ex vivo with the gene for human TM in the attempt to create a transient increase in TM expression. EPCs were evaluated for their expression of TM over time and their ability to1 remain adherent after exposure to laminar flow,2 produce APC,3 prevent platelet adhesion, and extend the clotting time of whole blood.4

Methods

EPC isolation and cell culture

All cells designated as “EPCs” in the current study were late outgrowth EPCs isolated and expanded from peripheral blood drawn from patients undergoing cardiac catheterization in the Duke University Medical Center who had documented advanced CAD by angiography. Patient clinical characteristics have been described previously.8 The Duke University Institutional Review Board approved the protocol for collection and use of human blood employed in the study.

EPC cultures were isolated and expanded (n=5) from 50 mL of peripheral blood as previously described.32 Late outgrowth EPCs were grown in endothelial complete media consisting of EBM-2 supplemented with EGM-2 SingleQuots (Lonza), 10% FBS (HyClone), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotics solution (Gibco). Cells were used at passages 5–10 for all experiments.

EPC cultures were previously characterized to confirm EC phenotype, which has been published elsewhere.8 EPCs expressed a similar phenotype to a control population of human aortic ECs (Lonza). EPCs had uniform expression of EC markers CD31 and CD105. Cells were negative for the stem cell marker CD133 as well as hematopoietic and monocytic markers CD45 and CD14. EPCs also expressed nitric oxide and were capable of forming tubular structures in Matrigel.

Virus production

Two different adenoviral type 5 vectors were used in this study. First, replication-deficient β-galactosidase adenovirus “control vector” (AdCV) was purchased (Eton Bioscience). AdCV stained cells blue after incubation with X-gal in proportion to the degree of transfection. AdCV was also used as a control vector to account for effects associated with transfection.

Second, replication-deficient adenoviral expressing human TM (AdTM) was a gift from Dawn Bowles, Duke University. Human cDNA for the TM gene was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The AdEasy system (Stratagene) was used to insert the human TM gene with a cytomegalovirus promoter into an adenoviral vector. Recombinant plasmids were identified by restriction digest and mass-produced in the recombination-deficient XL10-Gold ultracompetent bacterial strain (Stratagene). Purified recombinant Ad plasmid DNA was linearized and used to transfect an adenovirus packaging cell line, AD–293 cells, for large-scale viral production. Recombinant adenovirus was purified using cesium chloride gradients, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C for later use. The presence of replication-competent adenovirus was excluded by assessment of infectivity in COS1 cells and tested for replication competent virus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for E1a before use.

Adenoviral transfection optimization

Transfection

EPCs were transfected in EBM-2 with 2% FBS, and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution for either 4 or 24 h at 37°C with multiplicity of infections per cell (MOI) of 500, 100, 20, or 0. After transfection, cells were washed three times with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and a fresh endothelial complete medium was added. Following transfection optimization testing, a viral concentration of 100 MOI for 4 h was used for all subsequent experiments (n=4).

Transfection efficiency and TM surface expression

Transfection efficiency of EPCs was assessed by flow cytometry. EPCs were seeded into 12-well plates and transfected at confluency. Twenty-four hours after AdTM transfection, EPCs were detached using 0.025% trypsin (Lonza). Detached cells were resuspended 1:4 by volume with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD141 (BD Biosciences) and 10% goat serum for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and flow cytometric analysis was performed with FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). A fluorescence intensity threshold gate was set so that 1% of single native EPC cell events had fluorescence intensities falling above the gate. For all AdTM-EPC transfection conditions, the percentage of cells gated with respect to the initial threshold gate was recorded (n=4).

In the same experiment, surface expression of TM after transfection was assessed by flow cytometry with CD141-PE as described above. Mouse PE-conjugated IgG1 was used as isotype control (BD Biosciences). Mean fluorescence intensity from the respective isotype control was subtracted for all experiments (n=4).

Cell proliferation

EPCs were seeded into 12-well plates and allowed to grow for 1 day to reach a confluent density of 50,000 cells/cm2. The cells were transfected with AdTM for 4 or 24 h with 500, 100, 20, or 0 MOI. Twenty-four hours later, in order to mimic seeding the transfected cells onto new material at less than confluent density, EPCs were trypsinized and each well was transferred to a T-25 flask to allow room for cell expansion. The medium was changed the following day. Four days after transfection (3 days after typsinization from 12-well plate), EPCs within T-25s were trypsinized and counted in trypan blue solution to exclude dead cells (n=3).

Long-term TM expression

EPCs were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 30,000 cells/cm2. Cells were transfected with AdTM on the following day. Cultures were trypsinized 1, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after transfection. Detached cell populations were divided into two groups: half were used to evaluate mRNA expression of TM, and half were used for evaluate surface expression of TM as described above using PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD141 primary antibody (BD Biosciences). The medium was changed every other day during the experiment (n=3).

Cellular RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Minikit (Qiagen). The quantity and purity of all RNA samples were measured using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). Reverse transcription of 50 ng total RNA was performed with cDNA kit (Bio-Rad) and MyCycler (Bio-Rad). Reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR was performed using a SYBR-Green RT-PCR kit (Bio-Rad) and the MyIQ™ iCycler Optical Module (Bio-Rad). Whole-gene cDNA sequences of the target genes were obtained from PubMed, and TM and Beta-2 microglobulin primer sequences were generated using the online design program Primer3.33 The melt curves of the primers were examined after reaction with reference RNA, and primers were selected that had uniform and single-product melt curves. After results were obtained, fold change from the reference Beta-2 microglobulin RNA was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method (n=3).

Effect of shear stress on cell adhesion and morphology

Cells were seeded onto SlideFlasks (NUNC) at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 and transfected at confluency. The following day, the slides were placed in a parallel-plate flow chamber and connected to a circular flow setup consisting of a peristaltic pump (Cole Palmer), pulse dampener (Cole Palmer), and parallel-plate flow chamber as described previously.34 The flow media used consisted of EBM-2+5% FBS+1% antibiotic/antimycotic. Cells were exposed to 15 dyn/cm2 for 48 h. A mean shear stress of 15 dyn/cm2 represented a mean wall stress value larger or comparable in magnitude to human medium to large arteries such as the common carotid artery, aorta, femoral artery, and brachial artery.35 Controls consisted of cells under identical culture conditions, but not exposed to flow (static).

After exposure to flow, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformadehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X, and nonspecific binding was blocked with 10% goat serum (Sigma). Primary antibodies for CD31 (Invitrogen) (1:100) were incubated with the cells for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were rinsed multiple times and then incubated with a goat anti-mouse Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) (Invitrogen). F-actin was visualized with rhodamine phalloidin according to the manufacturers' instructions (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained with 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U (Nikon) inverted fluorescent microscope and a digital camera (DS-Qi1Mc; Nikon). The angle of cellular orientation was determined using ImageJ for 50 cells across four locations for each condition (n=4).

Assessment of TM function

APC production

The biological activity of EPC TM was assessed by measuring the rate at which protein C is cleaved by the TM-thrombin complex to form APC. EPCs were seeded into 24-well plates and transfected when confluent. One day after transfection, cultures were washed with Tyrodes buffer and 5 nM thrombin (Haematologic Technologies) was added for 5 min at 37°C. Four hundred nanometer human protein C (HTI) was added and duplicate 50 μL supernatant aliquots were removed at 0, 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min. Free thrombin was inhibited with equal volumes of TM stop solution (5 U/mL hirudin), 1 μM human antithrombin III (HTI), and 5 U/mL porcine heparin (Sigma- Aldrich) in Hank's buffered salt solution. A standard curve of APC (HTI) ranging from 0 to 25 nM was prepared and added to the 96-well plate. The APC formed was quantified with the addition of 100 μL/well of 400 mM Spectrozyme PCa (American Diagnostica) in a microtiter plate reader (BioTek Instruments) by the change in absorbance with time at 405 nm (n=4).

Platelet adhesion

EPCs were seeded onto 12-well plate and transfected at confluency, 24 h before blood collection. For use as a positive control, rat-tail collagen I (BD Biosciences) at 100 μg/mL in DPBS was plated overnight at 37°C. Blood from healthy human volunteers was drawn from the antecubital vein directly into blood collection tubes containing acid citrate dextrose for anticoagulation. All blood samples were used the same day.

Blood samples were centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min at room temperature and platelet-rich plasma was collected. Platelet-rich plasma (0.5 mL per well) was gently pipetted into each well. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, wells were washed with DPBS three times to thoroughly remove free platelets and the wells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde. Wells were blocked with 10% goat serum and then incubated for 30 min with mouse anti-human CD41 primary antibody (BD Biosciences). Cultures were rinsed in DPBS 3×and incubated with a goat anti-mouse Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:500) (Invitrogen). Five fields from each well were randomly selected and imaged with phase contrast and fluorescence to view EPC and platelet coverage, respectively. The percent area covered with adherent platelets was assessed with ImageJ (n=4).

Clotting assay

EPCs were seeded into six-well plates and transfected at confluency. The following day, blood was drawn from healthy individuals who had not taken any anticoagulant medication within the past week and collected into vacutainers filled with 3.2% buffered sodium citrate (BD). Wells were washed twice with DPBS without calcium chloride or magnesium chloride. The anti-coagulant citrate was reversed just before the assay by adding calcium chloride (0.105 M) at a 1:10 ratio to blood. Blood was added to each well and the plate was placed on a digital shaker (IKA) at 200 rpm at room temperature, and the time required for clot formation was recorded. All donated blood was used within 4 h after drawing (n=4).

Statistics

Differences among groups were assessed by multivariate analysis of variance, with the significance of individual differences established by post hoc Fisher's Protected Least Significant Difference Test. p-Values below 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

TM expression

Cultures of EPCs from patients with CAD were isolated and expanded from 50 mL of blood to obtain over 10 million late outgrowth EPCs in 7 out of 13 patients.8 Although EPC cultures were typically frozen lower passages, extrapolating the number of cells capable of being produced from a single culture, it would be possible to have over 30 million cells in less than 6 weeks for five out of seven CAD patients having EPC colonies. Some patient-derived cultures could be expanded to significantly higher number of cells; in one patient for example, over 350 million EPCs could be obtained after 6 weeks. A total of 20–30 million EPCs would likely be sufficient for seeding the lumen of a small-diameter synthetic vascular graft used for coronary artery bypass surgery at high seeding densities (10–15 cm long×0.4 cm inner diameter, with seeding density of 1.5×106 cells/cm2).36

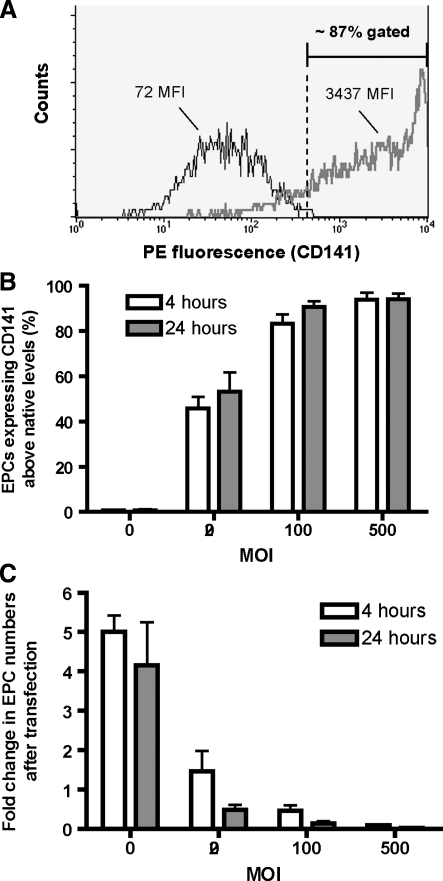

After confirming that EPC cultures expressed EC markers and were negative for hematopoetic and monocytic markers as previously described,8 the cells were transfected with an adenoviral vector. Transfection efficiency was determined by infecting EPCs with an adenoviral vector expressing human TM (AdTM) and performing flow cytometry (Fig. 1A, B). The percentage of transfected cells having fluorescent intensities higher than native cells increased significantly with dosage of viral particles (20, 100, and 500 MOI) (p<0.0001). There was no significant difference in percent transfected versus incubation time (4 h vs. 24 h; p=0.78). At the intermediate vector dosage of 100 MOI, 4 h incubation resulted in 83% cellular transfection, whereas 24 h incubation increased efficiency to 91%.

FIG. 1.

Optimization of adenoviral transfection of EPCs. EPCs were assessed for transfection efficiency after AdTM by flow cytometry for CD141-PE. Representative image of native EPCs (black line) and EPCs transfected 4 h with 100 MOI (bold line) (A). The percentage of EPC expressing CD141 higher than native EPCs increased with viral concentration (white bars: 4-h transfection time; gray bars: 24-h transfection time) (B). Four days after transfecting EPCs with AdTM, EPC numbers were decreased versus native EPCs (all cultures initially had 1.9×105 cells at transfection) (C). EPC, endothelial progenitor cell; AdTM, adenoviral expressing human thrombomodulin; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

Transfection of EPCs with AdTM caused a decrease in overall cell numbers as measured by average live cells per flask post transfection (Fig. 1C). EPCs were transfected in a 12-well plate using 20, 100, and 500 MOI for 4 and 24 h. To mimic the seeding of the transfected cells onto a new material at subconfluent density, 24 h post-transfection 190,000 cells were transferred to a T-25 flask and allowed to grow for 3 additional days before they were detached and counted. EPCs designated 0 MOI referred to those that underwent the same 4 day procedure minus the actual transfection step.

For 0 MOI EPCs, the number of cells increased by more than fourfold from the initial number of cells before transfection (Fig. 1C). In contrast, other than 20 MOI for 4 h, all AdTM dosages and incubation times inhibited the growth and decreased viability of EPCs relative to the 4-day proliferation of native cells. There was no significant difference in cell numbers overall between 4 and 24 h transfection (p=0.43). Control experiments with the replication-deficient AdCV revealed a similar decrease in cell numbers (data not shown), indicating that this effect arose from the transfection and not TM expression.

Clearly, an increase in per cell TM expression and loss of cell proliferation and viability presented a trade-off. A viral concentration of 100 MOI for 4 h was used for all subsequent experiments.

Time course of TM expression

Figure 2 shows the 3-week time course of TM expression for EPCs with a 4-hour incubation of 100 MOI AdTM for fold changes in both TM mRNA expression measured by RT-PCR and CD141 mean fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry. Both mRNA and surface CD141 expression peaked at 3 days before decreasing to near native levels after 21 days. All cultures remained confluent over the course of 21 days, indicating that there was no loss in cell coverage over time due to transfection.

FIG. 2.

Long-term TM expression measured through TM mRNA (A) and TM surface (B) expression in native and AdTM-transfected EPCs (*p<0.05 vs. native EPCs).

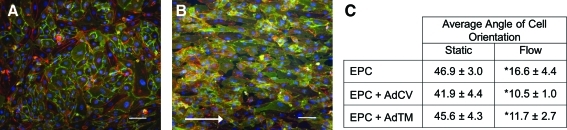

Orientation of EPCs subject to flow

Figure 3 shows EPCs transfected with 100 MOI AdTM for 4 h before and after exposure to 48 h in vitro laminar shear stress of 15 dyn/cm2. Cells were stained with CD31 (green) to indicate cell–cell borders, rhodamine phalloidin (red) to indicate F-actin, and Hoechst (blue) to indicate nuclei. Preflow cells show a typical cobblestone morphology (Fig. 3A), whereas postflow cells became elongated in the direction of flow (Fig. 3B). Figure 3C contains the angle between the major and minor axis of the cells averaged over 50 cells for native untransfected cells, and cells transfected with AdCV and AdTM. All preflow cases exhibited average angles of 42°–47° indicating random cellular orientation, whereas all post-flow cases showed average angles of 10°–17° indicating cellular alignment parallel to the direction of flow. The change in cellular orientation pre- and post-flow for all conditions was significant (p<0.0001), although there was no significance between native and transfected cells (p=0.78). EPCs remained adherent during exposure to flow for 48 h across all transfection conditions.

FIG. 3.

Transfected EPCs maintain firm adhesion and reorient in the direction of flow. Before exposure to flow, AdTM EPCs had random orientation and stained for PECAM (green), F-actin (red), and cell nuclei (blue) (A). After 48 h of laminar flow, AdTM-transfected EPCs remained adherent and aligned in the direction of flow (white arrow) (B) (scale bar 100 μm). EPC angle of orientation pre- and postexposure to flow (*p<0.0001 vs. static condition) (C). AdCV, adenovirus control vector. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

APC activity

Figure 4 shows the biological activity of TM protein expressed by EPCs transfected with 100 MOI AdTM or AdCV for 4 h, compared to basal expression measured for untransfected cells. Bare tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) wells were used as the negative control. All cells induced a significantly higher rate of APC production than did TCPS bare wells. TM activity of AdTM-transfected EPCs was fivefold greater than both native EPCs (p<0.05) and EPCs transfected with AdCV.

FIG. 4.

Activated protein C production rate of bare wells, EPCs, EPCs + AdCV, and EPCs + AdTM (*p<0.05 vs. bare well, #p<0.05 vs. native EPC and EPC + AdCV).

Platelet adhesion

Figure 5 contains overlaid fluorescent and phase-contrast images of immunolabeled platelets adherent to collagen I-positive control (Fig. 5A) and to confluent layers of untransfected EPCs (Fig. 5B), AdCV-transfected EPCs (Fig. 5C), and AdTM-transfected EPCs (Fig. 5D). The collagen control and AdTM-transfected EPCs showed the highest and lowest levels of platelet coverage, respectively, with platelets on collagen appearing the most spread.

FIG. 5.

Platelet area coverage was determined after 30-min incubation with platelet-rich plasma (A). Representative phase-contrast and fluorescent images showing EPCs and CD41-labeled platelets (green). Collagen I-coated wells had highest coverage (A), followed by EPCs (B), EPCs + AdCV (C), and EPCs + AdTM (D). Percent platelet area coverage was quantified (E). (*p<0.0001 vs. collagen coated well, #p<0.05 vs. native EPC or EPC + AdCV). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

The percent area covered by platelets was averaged over five fields of view for each of the conditions and is shown in Figure 5E. Native EPCs and EPCs transfected with AdCV both had reduced platelet adhesion compared to collagen I-coated wells (p<0.05), whereas EPCs with AdTM showed a threefold reduction in platelet adhesion compared to native EPCs (p<0.05) and a 12-fold reduction compared to collagen-coated wells (p<0.0001).

Clotting times

Figure 6 demonstrates the anticoagulant character of TM-overexpressing EPCs by determining whole blood clotting times in TCPS wells seeded with EPCs. Wells coated with native, untransfected EPCs, and AdCV-transfected EPCs both extended the 8 min clotting time of bare wells by 2 min (p<0.05), whereas wells coated with AdTM-transfected EPCs extended clotting times of bare wells by 4 min (p<0.01). Collagen-coated wells had longer clotting times than both bare TCPS wells and EPC-coated wells (EPCs clotted approximately 1 min before collagen-coated wells; data not shown) and were not considered as a positive control.

FIG. 6.

The clotting time of whole blood was measured on tissue culture polystyrene, and confluent layers of EPCs, EPC + AdCV, and EPC + AdTM (*p<0.05 vs. bare well, #p<0.05 vs. native EPC or EPC + AdCV).

Discussion

Lining biomaterials with autologous ECs is well known to improve the anti-thrombogenicity of blood-contacting implants. Human EPCs are an attractive autologous cell source for endothelialization therapy because they express key antithrombotic molecules and maintain adhesion to vascular materials while under physiological flow,13,14 and because they can be harvested non-invasively. EPC expression of TM in an important intrinsic antithrombotic mediator; however, aging and the presence of cardiovascular disease can alter cellular EC phenotype10–12 and reduce overall TM expression.20,21 Because cells isolated from patients with cardiovascular disease would be used for autologous vascular material endothelialization strategies, we investigated whether it was beneficial to augment the antithrombotic properties of patient-derived EPCs with the human gene for TM.

In the present study, patient-derived EPCs were transfected with an adenoviral vector for human TM. This system provided high levels of TM mRNA and TM protein expression over the first week, followed by a decrease in expression to basal levels over 21 days, which may be beneficial for the initial pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory environment found following the surgical implantation of a vascular construct.

TM expressed by EPCs transfected with AdTM was biologically active and increased the rate of APC production relative to untransfected EPCs by fivefold, an increase similar in magnitude to previous studies with TM-transfected vein graft segments37–40 and twice that of a human aortic EC control group (data not shown).

Functional testing of transfected EPCs involved reduction of platelet adhesion on TM-transfected EPC by threefold compared to untransfected EPCs, and by 12-fold compared to a collagen-coated well. We also observed that platelets adhering to collagen had increased spreading, whereas platelets on EPCs tended to appear rounded and attached preferentially at cell–cell junctions, a trend observed elsewhere.41

The significantly increased clotting time with TM-transfected EPCs was in agreement with prior studies demonstrating extended clotting time by ECs with adenoviral overexpression of the TM-promoter,42 and by material surfaces immobilized with TM at high densities.43 Surprisingly, blood clotting time on collagen-coated wells was longer than both TCPS and untransfected EPCs. The difference in clotting times between bare TCPS and collagen-coated wells may be due to the increased surface concentration of oxygen on TCPS, which has been shown to reduce clotting times.44 The disparity in clotting times of endothelialized surfaces and collagen-coated materials has also been observed elsewhere.45 Overall, the relatively modest differences in clotting time observed between conditions in this work may be due to a large fraction of the blood-contacting surface area being TCPS versus the EPC monolayer in all cases.46

We contend that the reduced platelet adhesion and extended clotting times by AdTM-transfected EPCs was due to increased thrombin inactivation and production of APC. This observation is similar in trend to the reduced platelet adhesion observed with biomaterials coated with thrombin inhibitors such as heparin and hirudin.47–50 Clotting studies of materials presenting anithrombotic molecules such as tissue plasminogen activator, hirudin, and heparin can also delay clot formation.51–54

Maintaining cell adhesion under flow conditions is also critical for long-term performance of endothelialized constructs that will be placed within the vasculature. TM-transfected EPCs remained adherent and reoriented during long term physiological flow, showing no deleterious effects on cell adhesion due to TM gene overexpression. Some strategies to bolster the anti-thrombogenicity of ECs involve the overexpression of proteolytic antithromboic molecules such as tissue plasminogen activator, but this technique results in reduced EC adhesion due to the gene product cleaving extracellular matrix proteins responsible for attaching ECs to the material.55

TM overexpression may improve the in vivo performance of EPC-endothelialized vascular materials such as small-diameter vascular grafts. Previous studies using TM overexpressing autologous vein grafts have reduced thrombosis39,40 and decreased intimal hyperplasia,39 and the endotheliaum may also be protected from inflammatory conditions that attenuate expression of TM.56,57 TM also has been immobilized on biomaterials58–60 with recent studies showing decreased thrombosis and intimal thickening in stent grafts.60

In sum, this study showed the feasibility of using TM overexpression to improve the anti-thrombotic performance of patient-derived late outgrowth EPCs. The adenoviral vector system employed here allowed us to deliver the TM gene to EPCs with high transfection efficiencies and robust protein expression similar to previous work.61 Transfection at an optimal viral concentration of 100 MOI for 4 h resulted in 83% EPC transfection. This viral concentration was 5- to 10-fold lower than that used in previous adenoviral gene therapy studies and human EPCs.62 While adenoviral vectors are well suited for examining efficacy in vitro, as we did here, there are several limitations with the use of this transfection vector that may prohibit their adoption for cardiovascular therapies in the clinic.

First, EPCs in the current study had altered cell growth after transfection and were unable to undergo subsequent expansion when replated at subconfluent density. The decreased cell numbers contrasts to work with lentiviral vectors where transfection results in no decrease in EC proliferation with cells capable of undergoing many population doublings after transfection.63 These data indicate that approximately twofold greater EPC numbers (compared to native EPCs) would be required before adenoviral transfection and material seeding. When transfected EPCs were seeded at confluent densities, we did not observe any change in total cell coverage over 21 days in our long-term TM expression tests or 2 day laminar flow experiments, suggesting that the transfected cells remain adherent.

Second, adenoviral transfection can also result in adaptive immune responses against viral proteins produced by the transfected cells resulting in inflammation and tissue necrosis.64 Third, transfection may be inhibited in many patients as the body contains preexisting immunity against the adenoviral vector. Approximately 50% of adults in the United States have neutralizing antibodies toward adenovirus type 5.65,66 Clearly, another transfection vehicle will have to be employed before human trials can be considered.

Conclusions

This study provides in vitro support for future animal testing of synthetic vascular grafts endothelialized with human EPCs overexpressing TM. We are currently conducting studies where the lumens of expanded small-diameter polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) vascular grafts are sodded with the native and TM-transfected EPCs that have been characterized in the current study. The sodded patient-derived EPCs are allowed to form confluent endothelial monolayers on the graft lumen, followed by surgical implantation as an interpositional graft in the femoral artery of an athymic rat to assess graft patency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dawn Bowles for supplying the TM adenoviral vector along with Bruce Klitzman and George Truskey for helpful discussions. We thank Michael Nichols for critical reading of the article. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL-44972.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Meinhart J.G. Deutsch M. Fischlein T. Howanietz N. Fröschl A. Zilla P. Clinical autologous in vitro endothelialization of 153 infrainguinal ePTFE grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:S327. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott-Burden T. Tock C.L. Bosely J.P. Clubb F.J., Jr. Parnis S.M. Schwarz J.J., et al. Nonthrombogenic, adhesive cellular lining for left ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 1998;98:II339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt D. Mol A. Breymann C. Achermann J. Odermatt B. Gossi M., et al. Living autologous heart valves engineered from human prenatally harvested progenitors. Circulation. 2006;114:I-125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannan R.Y. Salacinski H.J. Butler P.E. Hamilton G. Seifalian A.M. Current status of prosthetic bypass grafts: a review. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;74:570. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuigan A.P. Sefton M.V. The influence of biomaterials on endothelial cell thrombogenicity. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2547. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin M.-C. Almus-Jacobs F. Chen H.-H. Parry G.C.N. Mackman N. Shyy J.Y.J., et al. Shear stress induction of the tissue factor gene. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:737. doi: 10.1172/JCI119219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen S. Khan S. Al-Mohanna F. Batten P. Yacoub M. Native low density lipoprotein- induced calcium transients trigger VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1064. doi: 10.1172/JCI445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroncek J.D. Grant B.S. Brown M.A. Povsic T.J. Truskey G.A. Reichert W.M. Comparison of endothelial cell phenotypic markers of late-outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells isolated from patients with coronary artery disease and healthy volunteers. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3473. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guven H. Shepherd R.M. Bach R.G. Capoccia B.J. Link D.C. The number of endothelial progenitor cell colonies in the blood is increased in patients with angiographically significant coronary artery disease. J Am Coll of Cardiol. 2006;48:1579. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asahara T. Murohara T. Sullivan A. Silver M. van der Zee R. Li T., et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Y. Weisdorf D.J. Solovey A. Hebbel R.P. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:71. doi: 10.1172/JCI8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingram D.A. Mead L.E. Tanaka H. Meade V. Fenoglio A. Mortell K., et al. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104:2752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abou-Saleh H. Yacoub D. Theoret J.-F. Gillis M.-A. Neagoe P.-E. Labarthe B., et al. Endothelial progenitor cells bind and inhibit platelet function and thrombus formation. Circulation. 2009;120:2230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen J.B. Khan S. Lapidos K.A. Ameer G.A. Toward engineering a human neoendothelium with circulating progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:318. doi: 10.1002/stem.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaushal S. Amiel G.E. Guleserian K.J. Shapira O.M. Perry T. Sutherland F.W., et al. Functional small-diameter neovessels created using endothelial progenitor cells expanded ex vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1035. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griese D.P. Ehsan A. Melo L.G. Kong D. Zhang L. Mann M.J., et al. Isolation and transplantation of autologous circulating endothelial cells into denuded vessels and prosthetic grafts: implications for cell-based vascular therapy. Circulation. 2003;108:2710. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096490.16596.A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He H. Shirota T. Yasui H. Matsuda T. Canine endothelial progenitor cell-lined hybrid vascular graft with nonthrombogenic potential. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:455. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(02)73264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimmeler S. Leri A. Aging and disease as modifiers of efficacy of cell therapy. Circ Res. 2008;102:1319. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conboy I.M. Conboy M.J. Wagers A.J. Girma E.R. Weissman I.L. Rando T.A. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature. 2005;433:760. doi: 10.1038/nature03260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y. Herbert B.-S. Rajashekhar G. Ingram D.A. Yoder M.C. Clauss M., et al. Premature senescence of highly proliferative endothelial progenitor cells is induced by tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} via the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. FASEB J. 2009;23:1358. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coughlin S. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258. doi: 10.1038/35025229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esmon C.T. The protein C pathway. Chest. 2003;124:26S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.26s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murakami K. Okajima K. Uchiba M. Johno M. Nakagaki T. Okabe H., et al. Activated protein C attenuates endotoxin-induced pulmonary vascular injury by inhibiting activated leukocytes in rats. Blood. 1996;87:642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirose K. Okajima K. Taoka Y. Uchiba M. Tagami H. Nakano K., et al. Activated protein C reduces the ischemia/reperfusion-induced spinal cord injury in rats by inhibiting neutrophil activation. Ann Surg. 2000;232:272. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grey S.T. Tsuchida A. Hau H. Orthner C.L. Salem H.H. Hancock W.W. Selective inhibitory effects of the anticoagulant activated protein C on the responses of human mononuclear phagocytes to LPS, IFN-gamma, or phorbol ester. J Immunol. 1994;153:3664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grinnell B.W. Hermann R.B. Yan S.B. Human Protein C inhibits selectin-mediated cell adhesion: role of unique fucosylated oligosaccharide. Glycobiology. 1994;4:221. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosnier L.O. Griffin J.H. Inhibition of staurosporine-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells by activated protein C requires protease-activated receptor-1 and endothelial cell protein C receptor. Biochem J. 2003;373:65. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujiwara Y. Tagami S. Kawakami Y. Circulating thrombomodulin and hematological alterations in type 2 diabetic patients with retinopathy. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1998;5:21. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.5.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laszik Z.G. Zhou X.J. Ferrell G.L. Silva F.G. Esmon C.T. Down-Regulation of endothelial expression of endothelial cell protein C receptor and thrombomodulin in coronary atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:797. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61753-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner D.D. Burger P.C. Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2131. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095974.95122.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gawaz M. Langer H. May A.E. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3378. doi: 10.1172/JCI27196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broxmeyer H.E. Srour E. Orschell C. Ingram D.A. Cooper S. Plett P.A., et al. Cord blood stem and progenitor cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:439. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozen S. Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, editor; Misener S, editor. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Truskey G.A. Proulx T.L. Relationship between 3T3 cell spreading and the strength of adhesion on glass and silane surfaces. Biomaterials. 1993;14:243. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90114-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng C. Helderman F. Tempel D. Segers D. Hierck B. Poelmann R., et al. Large variations in absolute w all shear stress levels within one species and between species. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:225. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woo Y.J. Gardner T.J. Revascularization with cardiopulmonary bypass. In: Cohn L.H., editor; Edmunds L.H., editor. Cardiac Surgery in the Adult. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 581–607. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim A.Y. Walinsky P.L. Kolodgie F.D. Bian C. Sperry J.L. Deming C.B., et al. Early loss of thrombomodulin expression impairs vein graft thromboresistance: implications for vein graft failure. Circ Res. 2002;90:205. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.105097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabuchi N. Shichiri M. Shibamiya A. Koyama T. Nakazawa F. Chung J., et al. Non-viral in vivo thrombomodulin gene transfer prevents early loss of thromboresistance of grafted veins. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:995. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waugh J.M. Li-Hawkins J. Yuksel E. Kuo M.D. Cifra P.N. Hilfiker P.R., et al. Thrombomodulin overexpression to limit neointima formation. Circulation. 2000;102:332. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waugh J.M. Yuksel E. Li J. Kuo M.D. Kattash M. Saxena R., et al. Local overexpression of thrombomodulin for in vivo prevention of arterial thrombosis in a rabbit model. Circ Res. 1999;84:84. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J.J. Chen Y.M. Kurokawa T. Gong J.P. Onodera S. Yasuda K. Gene expression, glycocalyx assay, and surface properties of human endothelial cells cultured on hydrogel matrix with sulfonic moiety: effect of elasticity of hydrogel. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2010;95A:531. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Z. Kumar A. SenBanerjee S. Staniszewski K. Parmar K. Vaughan D.E., et al. Kruppel- like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates endothelial thrombotic function. Circ Res. 2005;96:e48. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159707.05637.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kishida A. Ueno Y. Fukudome N. Yashima E. Maruyama I. Akashi M. Immobilization of human thrombomodulin onto poly(ether urethane urea) for developing antithrombogenic blood-contacting materials. Biomaterials. 1994;15:848. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grunkemeier J.M. Tsai W.B. Horbett T.A. Hemocompatibility of treated polystyrene substrates: Contact activation, platelet adhesion, and procoagulant activity of adherent platelets. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:657. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980915)41:4<657::aid-jbm18>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGuigan A.P. Sefton M.V. The thrombogenicity of human umbilical vein endothelial cell seeded collagen modules. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2453. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streller U. Sperling C. Hübner J. Hanke R. Werner C. Design and evaluation of novel blood incubation systems for in vitro hemocompatibility assessment of planar solid surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater. 2003;66B:379. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao D. Wang X. Lin P.H. Yao Q. Chen C.J. Covalent linkage of heparin provides a stable anti-coagulation surface of decellularized porcine arteries. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2736. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amiji M. Park K. Surface modification of polymeric biomaterials with poly(ethylene oxide), albumin, and heparin for reduced thrombogenicity. J Biomater Sci, Polym Ed. 1993;4:217. doi: 10.1163/156856293x00537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai C.-C. Chang Y. Sung H.-W. Hsu J.-C. Chen C.-N. Effects of heparin immobilization on the surface characteristics of a biological tissue fixed with a naturally occurring crosslinking agent (genipin): an in vitro study. Biomaterials. 2001;22:523. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin J.-C. Tseng S.-M. Surface characterization and platelet adhesion studies on polyethylene surface with hirudin immobilization. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2001;12:827. doi: 10.1023/a:1017937304964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seifert B. Romaniuk P. Groth T. Covalent immobilization of hirudin improves the haemocompatibility of polylactide-polyglycolide in vitro. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1495. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oltrona L. Eisenberg P.R. Abendschein D.R. Rubin B.G. Efficacy of local inhibition of procoagulant activity associated with small-diameter prosthetic vascular grafts. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:624. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lahann J. Pluster W. Klee D. Gattner H.G. Hocker H. Immobilization of the thrombin inhibitor r-hirudin conserving its biological activity. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2001;12:807. doi: 10.1023/a:1013929103147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang I.K. Kwon O.H. Kim M.K. Lee Y.M. Sung Y.K. In vitro blood compatibility of functional group-grafted and heparin-immobilized polyurethanes prepared by plasma glow discharge. Biomaterials. 1997;18:1099. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunn P.F. Newman K.D. Jones M. Yamada I. Shayani V. Virmani R., et al. Seeding of vascular grafts with genetically modified endothelial cells. Secretion of recombinant TPA results in decreased seeded cell retention in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 1996;93:1439. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conway E.M. Rosenberg R.D. Tumor necrosis factor suppresses transcription of the thrombomodulin gene in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5588. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore K.L. Esmon C.T. Esmon N.L. Tumor necrosis factor leads to the internalization and degradation of thrombomodulin from the surface of bovine aortic endothelial cells in culture. Blood. 1989;73:159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J.-m. Singh M.J. Nelson P.R. Hendricks G.M. Itani M. Rohrer M.J., et al. Immobilization of human thrombomodulin to expanded polytetrafluoroethylene. J Surg Res. 2002;105:200. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sperling C. Salchert K. Streller U. Werner C. Covalently immobilized thrombomodulin inhibits coagulation and complement activation of artificial surfaces in vitro. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5101. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong G. Li J.-m. Hendricks G. Eslami M.H. Rohrer M.J. Cutler B.S. Inhibition of experimental neointimal hyperplasia by recombinant human thrombomodulin coated ePTFE stent grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:608. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kealy B. Liew A. McMahon J.M. Ritter T. O'Doherty A. Hoare M., et al. Comparison of viral and nonviral vectors for gene transfer to human endothelial progenitor cells. Tissue Eng Part C: Methods. 2009;15:223. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murasawa S. Llevadot J. Silver M. Isner J.M. Losordo D.W. Asahara T. Constitutive human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression enhances regenerative properties of endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1133. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027584.85865.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van den Biggelaar M. Bouwens E.A.M. Kootstra N.A. Hebbel R.P. Voorberg J. Mertens K. Storage and regulated secretion of factor VIII in blood outgrowth endothelial cells. Haematologica. 2009;94:670. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zaiss A.K. Machado H.B. Herschman H.R. The influence of innate and pre-existing immunity on adenovirus therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:778. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sumida S.M. Truitt D.M. Lemckert A.A.C. Vogels R. Custers J.H.H.V. Addo M.M., et al. Neutralizing antibodies to adenovirus serotype 5 vaccine vectors are directed primarily against the adenovirus hexon protein. J Immunol. 2005;174:7179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parker A.L. Waddington S.N. Buckley S.M.K. Custers J. Havenga M.J.E. van Rooijen N., et al. Effect of neutralizing sera on factor X-mediated adenovirus serotype 5 gene transfer. J Virol. 2009;83:479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01878-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]