Abstract

The microbial capsular polysaccharide glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) from the opportunistic fungus Cryptoccocus neoformans is able to alter the innate and adaptive immune response through multi-faceted mechanisms of immunosuppression. The ability of GXM to dampen the immune response involves the induction of T cell apoptosis, which is dependent on GXM-induced up-regulation of Fas ligand (FasL) on antigen-presenting cells. In this study we elucidate the mechanism exploited by GXM to induce up-regulation of FasL. We demonstrate that (i) the activation of FasL is dependent on GXM interaction with FcgammaRIIB (FcγRIIB); (ii) GXM induces activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 signal transduction pathways via FcγRIIB; (iii) this leads to downstream activation of c-Jun; (iv) JNK and p38 are simultaneously, but independently, activated; (v) FasL up-regulation occurs via JNK and p38 activation; and (vi) apoptosis occurs via FcγRIIB engagement with consequent JNK and p38 activation. Our results highlight a fast track to FasL up-regulation via FcγRIIB, and assign to this receptor a novel anti-inflammatory role that also accounts for induced peripheral tolerance. These results contribute to our understanding of the mechanism of immunosuppression that accompanies cryptococcosis.

Keywords: apoptosis, capsular polysaccharides, Fc receptors, monocytes/macrophages, signal transduction

Introduction

Compounds that interact with the immune system to up-regulate or down-regulate specific aspects of the host response can be classified as immunomodulators or biological response modifiers [1]. Peptides such as cytokines and chemokines are well-known examples of such molecules. Recently, certain polysaccharides of microbial origin have been described as potent immunomodulators with specific activity for both antigen-presenting cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, and T cells. To date, relatively few polysaccharides have been identified as immunomodulators [2].

Glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) is the most important component of the Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide capsule and is found bound to the fungal cell to form a capsule, or shed in soluble form during growth in vivo and in vitro. GXM interaction with several natural effector cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells has been described. Furthermore, monocytes/macrophages show long-lasting storage of GXM in the intracellular compartment. GXM directly affects multiple functions of innate immune cells by reducing major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression [3,4], dendritic cell maturation [5] and proinflammatory cytokine production [6]. Moreover, GXM induces production of inhibitory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10 [7,8]. Indeed, by reducing the activity of antigen-presenting cells, GXM inhibits T cell proliferation [9,10], dampens T helper type 1 (Th1) response [10,11] and induces apoptosis of T cells [12,13]. In addition, in a recent report we demonstrated that GXM displays potent anti-inflammatory properties when evaluated in an in vivo experimental model of rheumatoid arthritis. This beneficial effect is accompanied by a drastic decrease in proinflammatory cytokine production as well as inhibition of Th17 differentiation [14].

GXM interaction with immune cells is mediated by several receptors such as CD14, Toll-like receptor (TLR-4), CD18 and FcγRIIB; all these, with the exception of FcγRIIB, are considered activating receptors [15]. However, the final outcome of GXM interaction with the immune system is severe suppression of both innate and adaptive immunity [16]. Notably, FcγRIIB is an important inhibitory receptor and a major receptor for GXM. In a recent paper we demonstrated that GXM transduces inhibitory effects through FcγRIIB via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) involvement and Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5′ phosphatase (SHIP) recruitment [17].

In a previous report, we demonstrated that GXM, as well as inducing immunosuppression, also induces apoptosis of T cells via up-regulation of Fas ligand (FasL) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [12]. In particular we demonstrated that: (i) GXM induces up-regulation of the death receptor FasL in GXM-loaded macrophages and (ii) these cells induce apoptosis of activated T cells and Jurkat T cells via the FasL/Fas pathway. Despite the wealth of studies regarding the pathway leading to apoptosis via caspase activation, little is known about the mechanism that induces FasL up-regulation. Previous studies found that signal transduction by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) plays a key role in a variety of cellular responses, including proliferation, differentiation and cell death [18,19]. In this study we analyse the mechanism involved in GXM-mediated FasL up-regulation and apoptosis. In particular, the role of GXM/FcγRIIB interaction and the signal transduction that leads to FasL up-regulation are studied.

Materials and methods

Reagents and media

RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine was obtained from Gibco BRL (Paisley, Scotland, UK). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin–streptomycin solution and irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Blocking goat polyclonal IgG to FcγRIIB was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA), rabbit polyclonal antibodies to FasL, phospho-c-Jun (Ser 63/73) and actin (H-300) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal IgG to phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185, Thr221/Tyr223) and to phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) were purchased from Upstate Cell Signaling (NY, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories. P38 inhibitor (SB 203580) and JNK inhibitor (SP 600125) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) to FasL (IgG1 isotype) was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Cyanine 3 (Cy3)-conjugated rabbit polyclonal anti-goat IgG was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA). Mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER) and Restore Western blot stripping buffer were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Immun-Star™ HRP chemiluminescent kit was purchased from Bio-Rad. PHA was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

All media used for cell culture were negative for endotoxin as detected by Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Sigma-Aldrich), which had a sensitivity of approximately 0·05–0·1 ng of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) per ml.

MonoMac6 cell line

The human MonoMac6 cell line [20] (DSMZ ACC 124) was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Culture. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine medium supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cryptococcal polysaccharides

GXM was isolated from the culture supernatant fluid of serotype A strain (CN 6) grown in liquid synthetic medium in a gyratory shaker for 4 days at 30°C. GXM was isolated by differential precipitation with ethanol and hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) [21]; the procedure has been described in detail previously [22]. Soluble GXM isolated by the above procedure contained < 125 pg LPS/mg of GXM as detected by Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (QCl-1000; BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis of FasL expression on MonoMac6 cells

MonoMac6 (1 × 106/ml) cells were incubated with antibody to FcγRIIB (0·1 µg/ml) or irrelevant goat polyclonal IgG (0·1 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C in RPMI-1640, or in the presence and absence of JNK inhibitor SP 600125 (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (1 µM) for 30 min at 37°C, and then incubated in the presence and absence of GXM (100 µg/ml) in RPMI-1640 for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation, fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS containing 0·5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0·4% sodium azide (fluorescence buffer, FB) and stained with PE-labelled mAb to FasL (20 µl/106 cells) in FB for 40 min on ice. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with FB, then 5000 events were analysed by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACScan) (BD Biosciences). Autofluorescence was assessed using untreated cells.

Flow cytometry analysis of JNK, p38 and c-Jun activation

MonoMac6 (1 × 106/ml) cells were incubated with antibody to FcγRIIB (0·1 µg/ml) or irrelevant goat polyclonal IgG (0·1 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C in RPMI-1640 and in the presence and absence of JNK inhibitor SP 600125 (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (1 µM) for 30 min at 37°C, and then incubated in the presence or absence of GXM (100 µg/ml) in RPMI-1640 for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were collected by centrifugation, fixed in 1·5% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and treated with ice-cold methanol (500 µl/106 cells) for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice in PBS containing 1% BSA and stained with polyclonal antibodies to p-JNK (1:200), p-p38 (1:100) or p-c-Jun (1:20) in PBS 1% BSA for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS 1% BSA, stained with FITC-conjugated goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG (1:200) or Cy3-conjugated rabbit polyclonal anti-goat IgG (1:100), washed twice more in PBS 1% BSA, then 5000 events were analysed by FACScan (BD Biosciences). Autofluorescence was assessed using untreated cells.

Western blotting for phospho-JNK, phospho-p38 MAP kinase, phospho-c-Jun and FasL

MonoMac6 (1 × 106/ml) cells were incubated alone or with JNK inhibitor SP 600125 (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (1 µM) for 30 min at 37°C, or with antibody to FcγRIIB or irrelevant goat polyclonal IgG (0·1 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C. After culture, the cells were incubated alone or with GXM (100 µg/ml) in RPMI-1640 for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were washed and lysed with M-PER in the presence of protease inhibitors (BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations were determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent kit (Pierce). The lysates (100 µg of each sample) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pierce) for 1 h at 100 V in a blotting system (Bio-Rad) for Western blot analysis. Membranes were then placed in blocking buffer, and incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal antibody to phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185, Thr221/Tyr223) (1:1000). Membranes were stripped, blocked and incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody to phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) (1:1000) in blocking buffer, stripped, blocked and incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody to phospho-c-Jun (Ser 63/73) (1:1000) in blocking buffer, stripped again and incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody to FasL (1:1000). Immunoblotting with the rabbit polyclonal anti-actin antibody (H-300) (1:200) was performed in the same membrane and was used as an internal loading control to ensure equivalent amounts of protein in each lane. Detection was achieved using appropriate HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG, followed by Immun-Star™ HRP chemiluminescent kit (Bio-Rad). Immunoreactive bands were visualized and quantified by Chemidoc Instruments (Bio-Rad).

Preparation of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL)

Heparinized venous blood was obtained from healthy donors. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia), as described previously [23]. For lymphocyte purification, PBMC were plated on culture flasks for 1 h in RPMI-1640 plus 5% FCS at 37°C and 5% CO2. After incubation, the non-adherent fraction was collected and cells (5 × 106/ml) were treated with PHA (5 µg/ml) for 48 h at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Apoptosis

MonoMac6 (1 × 106/ml) cells were incubated alone or with antibody to FcγRIIB (0·1 µg/ml) or irrelevant goat polyclonal IgG (0·1 µg/ml) in RPMI-1640 at 10% of FCS for 30 min at 4°C, or alone or with JNK inhibitor SP 600125 (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor SB 203580 (1 µM) in RPMI-1640 at 10% of FCS for 30 min at 37°C. After this the cells were stimulated with GXM (100 µg/ml) for 2 h. Cells were washed and incubated successively with lymphocytes (PBL) treated previously with PHA, as described above, at an effector : target ratio (E : T) = 10/1. The percentage of lymphocytes (PBL) undergoing apoptosis was quantified after 24 h of incubation by staining with propidium iodide (PI) (50 µg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich). The PI analysis was performed because, unlike annexin V, which detects the early stages of apoptosis [24], it measures total apoptosis rate [25]. Briefly, cells were centrifuged, resuspended in hypotonic PI solution and kept for 1 h at room temperature. Apoptosis was evaluated as described previously [26].

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) from three to seven replicate experiments. Data were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (anova). Post-hoc comparisons were made with Bonferroni's test. A value of P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Role of FcγRIIB in GXM-induced FasL overexpression

We have demonstrated previously that GXM elicits a potent increase in cell surface FasL expression in macrophages, and this effect was achieved by increasing the FasL synthesis [12]. GXM is recognized by several surface receptors including TLR-4, CD14 and CD18, as well as FcγRIIB [15]. Indeed, FcγRIIB is responsible for 70% of macrophage uptake. As a consequence, the possible role of FcγRIIB in GXM-mediated FasL up-regulation was assessed.

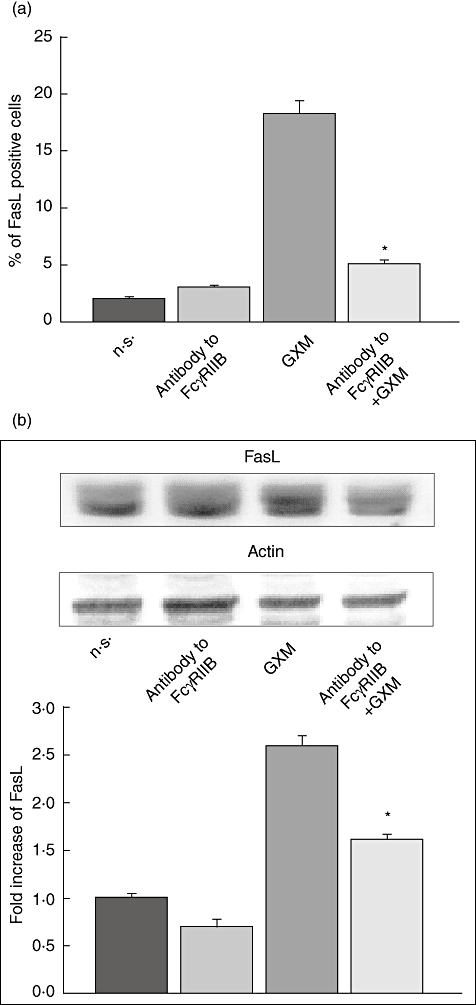

In a first series of experiments, MonoMac6 cells were treated for 30 min at 4°C with antibody to FcγRIIB and then incubated with 100 µg/ml of GXM for 2 h at 37°C. This was the concentration found in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of a group of cryptococcosis patients [27]. FasL expression was measured by cytofluorimetric analysis. The results (Fig. 1) show that, as expected, GXM induced up-regulation of FasL. A significant (P < 0·05) reduction in FasL expression, evidenced as the percentage of FasL-positive cells, was produced by blocking FcγRIIB (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, a significant (P < 0·05) reduction in FasL protein expression levels was also observed in Western blotting experiments (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Role of FcγRIIB on glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-induced Fas ligand (FasL) surface up-regulation. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), pretreated and non-treated with antibody to FcγRIIB (0·1 µg/ml) were cultured for 2 h in the presence or absence of GXM (100 µg/ml) and analysed by flow cytometry or Western blotting. (a) Percentage of FasL-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. (b) Western blotting for FasL. Actin was used as loading control. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the actin intensity in the same lane. FasL level was quantified in relation to untreated cells. Blots are representative of results obtained from five separate experiments with similar results. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m. of five experiments. (a,b) Incubation with irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G did not affect FasL expression. *P < 0·05 (antobody to FcγRIIB plus GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

JNK and p38 MAPK are activated by GXM

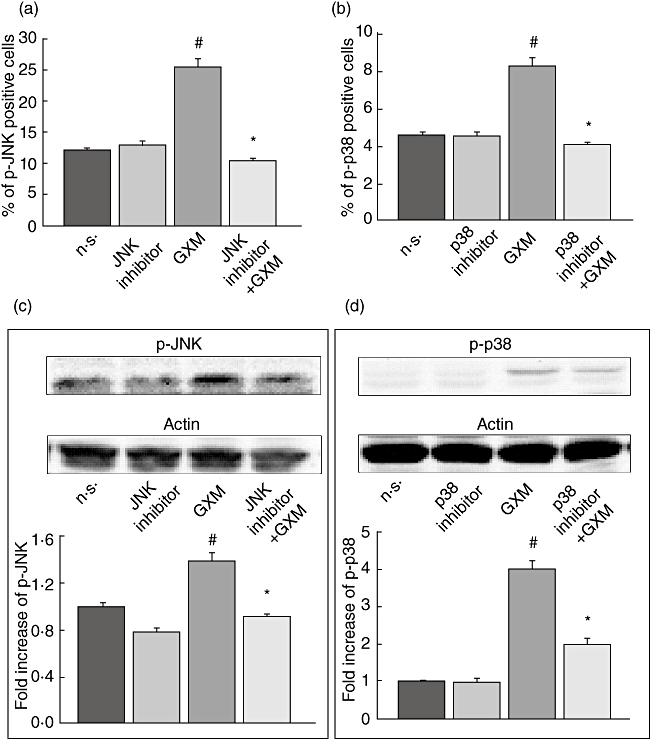

It has been reported that p38 MAPK and JNK may be involved in the regulation of FasL expression [28–30]. Therefore, MonoMac6 cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C both in the presence and absence of SP 600125, a specific inhibitor of JNK catalytic activity [31], or SB 203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 catalytic activity [32], then GXM was added to the cells for 2 h. The optimal dose of the specific inhibitors (SP 600125 or SB 203580) was determined in preliminary experiments. On the basis of these results, 0·5 µM was used for JNK inhibitor and 1 µM was used for p38 MAPK inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 2, GXM induced activation of JNK and p38 MAPK; this activation was blocked by using specific inhibitors. Activation was demonstrated by cytofluorimetric analysis (Fig. 2a,b), which showed an increase in the percentage of p-JNK as well as p-p38-positive cells after GXM treatment. The effect was completely lost in the presence of specific inhibitors. Up-regulation of p-JNK and p-p38 expression, and the inhibition of this effect in the presence of specific inhibitors was also observed through Western blotting analysis (Fig. 2c,d).

Fig. 2.

Effect of glucuronoxylomamman (GXM) treatment on c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 activation. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml) pretreated or not with JNK inhibitor (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor (1 µM), were incubated for 2 h in the presence or absence of GXM (100 g/ml) and analysed by flow cytometry or Western blotting. (a,b) Percentage of p-JNK and p-p38-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. (c,d) Western blotting for p-JNK and p-p38. Cells treated with diluent (dimethylsulphoxide) were also run in parallel; the results were similar to those obtained in absence of inhibitors. Actin was used as loading control. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the actin intensity in the same lane. Blots are representative of five independent experiments with similar results. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m. of five experiments. (a,b,c,d) #P < 0·05 (GXM treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (JNK or p38 inhibitor plus GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

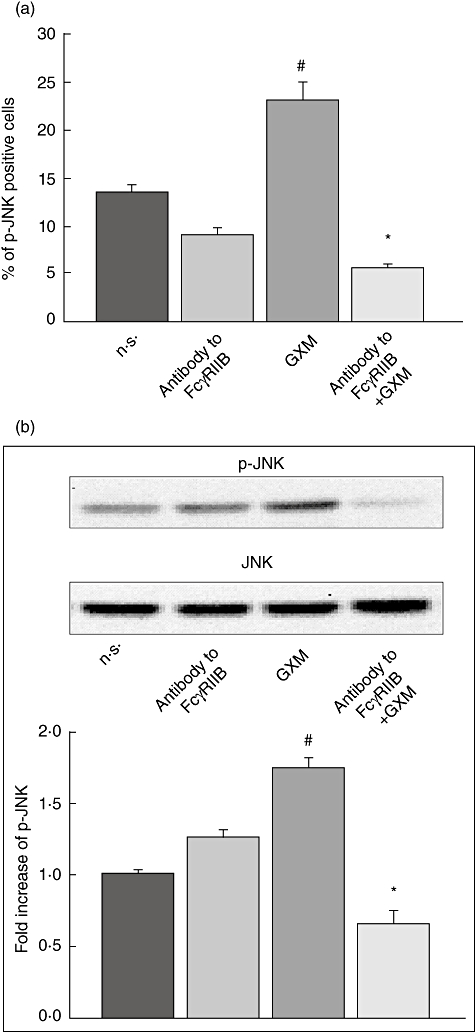

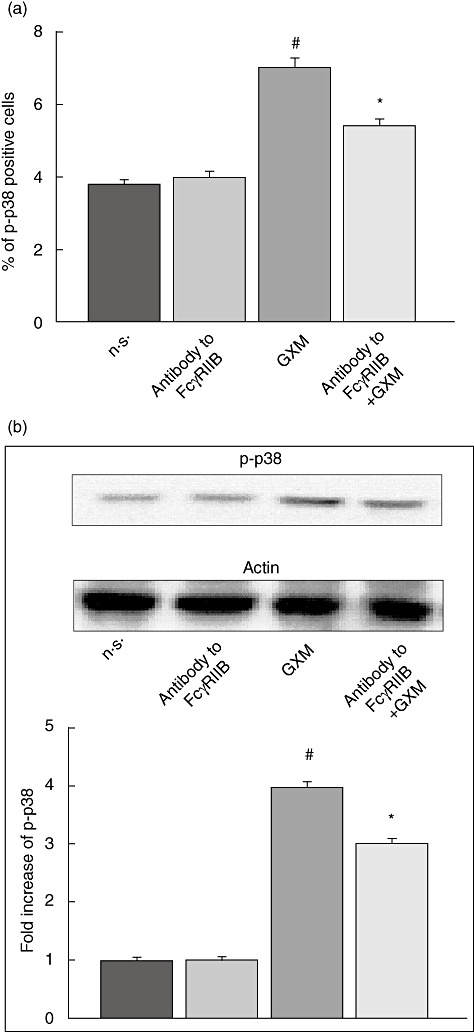

To determine whether these kinases were activated via FcγRIIB engagement, MonoMac6 cells were treated with polyclonal antibody to FcγRIIB for 30 min at 4°C and then GXM was added for 2 h at 37°C. As shown in Fig. 3 the GXM-mediated up-regulation of p-JNK was completely abrogated by blocking the interaction of GXM with FcγRIIB whereas, as shown in Fig. 4, the up-regulation of p-p38 was inhibited significantly even if not completely blocked. These results were obtained by using cytofluorimetric analysis (Figs 3a and 4a) and Western blotting analysis (Figs 3b and 4b).

Fig. 3.

Role of FcγRIIB in glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) activation. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), treated as described in Fig. 1, were stained with antibodies to p-JNK and analysed by flow cytometry or Western blotting. (a) Percentage of p-JNK-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. (b) Western blotting for p-JNK. JNK was used as loading control. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the JNK intensity in the same lane. Blot is representative of results obtained from five separate experiments. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m. of five experiments. (a,b) The incubation with irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G did not affect JNK activation. #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (antibody to FcγRIIB plus GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

Fig. 4.

Role of FcγRIIB in glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-induced p38 activation. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), treated as described in Fig. 1, were stained with antibodies to p-p38, and analysed by flow cytometry or Western blotting. (a) Percentage of p-p38-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. (b) Western blotting for p-p38. Actin was used as loading control. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the actin intensity in the same lane. Blots are representative of results obtained from five separate experiments. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m. of five experiments. (a,b) The incubation with irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G did not affect p38 activation. #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (antibody to FcγRIIB plus GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

C-Jun is activated by GXM

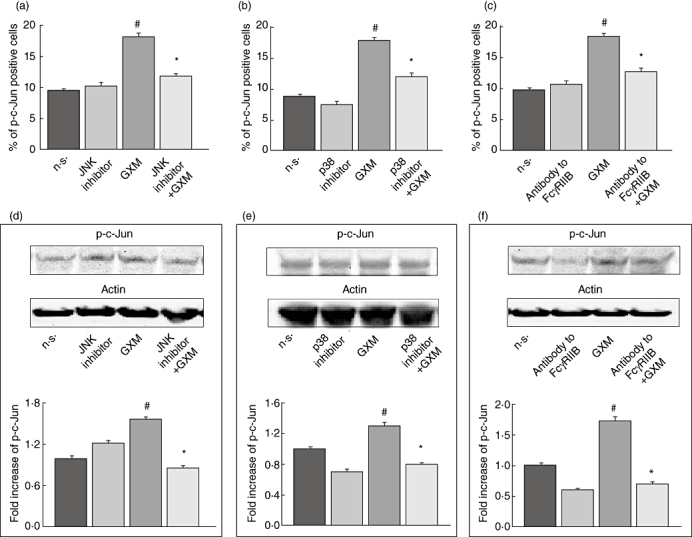

C-Jun is an important component of the activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factor complex whose induction is mainly mediated directly by JNK and indirectly by p38 MAPK cascades [18,33–35]. Thus, MonoMac6 cells were incubated alone or with GXM for 2 h. The results obtained by cytofluorimetric analysis showed that GXM induced activation of c-Jun (Fig. 5a–c). Similar results were obtained by Western blotting (Fig. 5d–f). In addition, treatment of cells with specific inhibitors of JNK or p38 resulted in a significant reduction of c-Jun activation. These results were obtained by cytofluorimetric analysis (Fig. 5a,b) and confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 5d,e). To investigate the possibility that activation of c-Jun is mediated, at least in part, by the GXM uptake via FcγRIIB, we blocked GXM binding to FcγRIIB. For this purpose, cells were treated with polyclonal antibody to FcγRIIB and then GXM was added for 2 h. The results showed that activation of c-Jun was down-regulated when FcγRIIB engagement was blocked. Results obtained by using cytofluorimetric analysis were similar to those obtained by Western blotting (Fig. 5c,f).

Fig. 5.

Role of FcγRIIB, p38 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) in glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-induced c-Jun activation. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), pretreated and non-treated, with antibody to FcγRIIB (0·1 µg/ml) or JNK inhibitor (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor (1·0 µM) were incubated for 2 h in the presence or absence of GXM (100 µg/ml). The analysis was performed by flow cytometry and Western blotting. (a,b,c) Percentage of p-c-Jun-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. (d,e,f) Western blotting for p-c-Jun. Actin was used as loading control. Cells treated with diluent (dimethylsulphoxide) were also run in parallel; the results were similar to those obtained in absence of inhibitors. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the actin intensity in the same lane. C-Jun activation was quantified relative to untreated cells. Blots are representative of five independent experiments with similar results. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m of five experiments. The incubation with irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G did not affect c-Jun activation. (a,b,c,d,e,f) #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (JNK inhibitor, p38 inhibitor or antibody to FcγRIIB plus GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

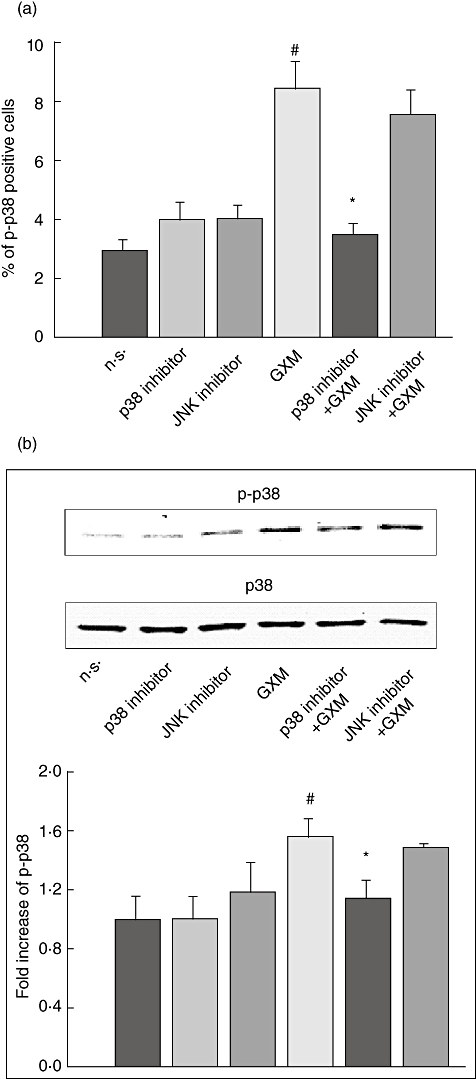

P38 MAP kinases are activated by GXM independently of JNK

Given that both JNK and p38 MAPK are activated simultaneously by GXM, we wanted to determine whether these two pathways were activated independently. For this purpose, GXM-induced activation of p38 MAPK was tested in the presence or absence of JNK inhibitor (SP 600125). Cells were treated with JNK inhibitor or p38 inhibitor (SB 203580) for 30 min at 37°C and then GXM was added for 2 h. As shown in Fig. 6, JNK inhibition did not affect the GXM-induced activation of p38.

Fig. 6.

p38 activation induced by glucuronoxylomamman (GXM) is not inhibited by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) blockade. MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml) pretreated and non-treated, with JNK inhibitor (0·5 µM) or p38 inhibitor (1 µM) were incubated for 2 h in the presence or absence of GXM (100 µg/ml). Cells were stained with antibodies to p-p38 and analysed by flow cytometry or Western blotting. (a) Percentage of p-p38-positive cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (p38 inhibitor GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated). (b) Western blotting for p-p38. P38 was used as loading control. Cells treated with diluent (dimethylsulphoxide) were also run in parallel and the results were similar to those obtained in the absence of inhibitors. Optical density (OD) of reactive bands was measured and normalized by the p38 intensity in the same lane. P38 activation was quantified relative to untreated cells. The blot is representative of three independent experiments with similar results. The fold increase is the mean ± s.e.m. of three experiments. #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 (p38 inhibitor GXM-treated, versus GXM-treated).

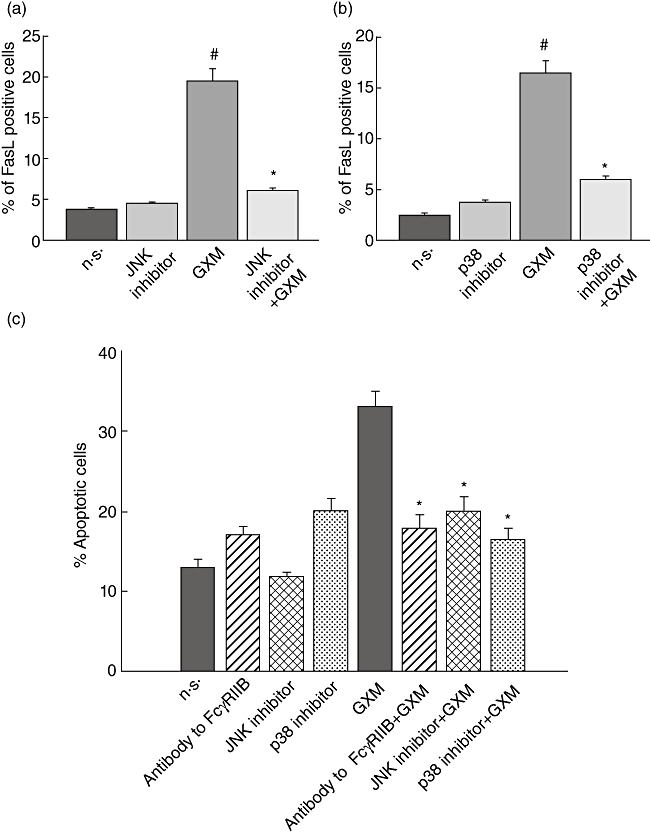

JNK and p38 MAPK are necessary for GXM-induced up-regulation of FasL expression

Several studies have found that JNK and p38 are involved in the regulation of FasL expression [28–30]; therefore, we tested whether these intracellular signals were involved in GXM-induced FasL up-regulation in our experimental conditions. Cells were treated with inhibitors of JNK or p38 and then GXM was added to the cells for 2 h. Cytofluorimetric analysis was performed; the results showed that inhibition of JNK or p38 activation resulted in inhibition of FasL up- regulation (Fig. 7a,b).

Fig. 7.

Evaluation of Fas ligand (FasL) surface up-regulation and glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-induced apoptosis. (a,b) MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), treated as described in Fig. 2, were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled monoclonal antibody (mAb) to FasL and percentage of FasL-positive cells was analysed by flow cytometry. Bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of three experiments. #P < 0·05 (GXM-treated versus untreated); *P < 0·05 [c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) or p38 inhibitor GXM- treated, versus GXM-treated]. (c) MonoMac6 cells (1 × 106/ml), treated as described in Fig. 5, were incubated with peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), pretreated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) as described in Materials and methods, at an effector : target ratio (E : T) = 10/1. The percentage of PBL undergoing apoptosis was quantified after 24 h of incubation by propidium iodide (PI) staining and analysed using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACScan) flow cytofluorometer. The PBL apoptosis rate resulted similar whether in the presence or absence of MonoMac not treated with GXM. Bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. of seven experiments. The incubation with irrelevant goat polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)G did not affect PBL apoptosis *P < 0·05 (antibody to FcγRIIB, or JNK or p38 inhibitors plus GXM-treated versus GXM-treated).

Apoptosis is induced by FcγRIIB engagement

Given that FasL up-regulation is greatly responsible for apoptosis induction, we evaluated the effect of FcγRIIB blockade on GXM-induced apoptosis of cells. MonoMac6 cells were treated with antibody to FcγRIIB or with inhibitors of JNK or p38 MAPK, then GXM was added. After 2 h of incubation, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), both activated and not activated, were added, and apoptosis was evaluated after 1 day of culture. The results (Fig. 7c) showed that an inhibition of apoptosis was observed in the presence of Ab to FcγRIIB as well as with inhibitors of JNK or p38 MAPK. Conversely, cells not treated with PHA did not show significant variations in apoptosis.

Discussion

Microbial polysaccharides from bacteria or fungi are an inexhaustible source of biopharmaceutical compounds. Some of these have received attention, such as curdlan, which shows anti-tumour and anti-viral activity [36]. In addition, many of these compounds are classified as biological response modifiers [1]. This study is devoted to clarifying the immunoregulatory mechanism ascribed to GXM, a capsular polysaccharide of the opportunistic fungus C. neoformans. The ability of GXM to induce immunosuppression has been reported previously and mechanisms contributing to immunosuppression have, at least in part, been elucidated. GXM can interact with macrophages via cell surface receptors such as TLR-4, CD14, CD18, FcγRIIB [15], and the main immunosuppressive effects are mediated by GXM uptake via FcγRIIB. The capacity of GXM to dampen the immune response involves the induction of T cell apoptosis. This effect is dependent on GXM-induced up-regulation of FasL on antigen-presenting cells [15]. In the present study we describe the mechanism exploited by GXM to induce up-regulation of FasL, which leads to apoptosis induction. In particular, we demonstrate that: (i) activation of FasL is dependent on GXM interaction with FcγRIIB; (ii) GXM is able to induce activation of JNK and p38 signal transduction pathways; (iii) this leads to downstream activation of c-Jun; (iv) JNK and p38 are simultaneously, but independently, activated; (v) activation of JNK, p38 MAPK and c-Jun is dependent on GXM interaction with FcγRIIB; (vi) FasL up- regulation occurs via JNK and p38 activation; and (vii) apoptosis occurs via FcγRIIB engagement with consequent JNK and p38 activation.

FcγRIIB, via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM) in its intracytoplasmatic domain, is responsible for negative immunoregulation [37]. This action is consistent with our previous data demonstrating GXM uptake via FcγRIIB and the consequent inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine release by phagocytic cells. These effects are lost completely when the interaction of GXM with FcγRIIB is blocked [17]. Moreover, we have demonstrated previously the capacity of GXM to dampen the immune response in an experimental model of collagen-induced arthritis [14], an effect that possibly occurs upon engagement of FcγRIIB [38].

FcγRIIB engagement by GXM, with consequent SHIP activation, appears to be a critical event that produces anti-inflammatory effects by blocking nuclear factor κB (NFκB) activation [14]. Moreover, it has been reported that FcγRIIB is a regulator of apoptosis [39]. In this paper, for the first time, we provide evidence that FcγRIIB is involved in the up-regulation of FasL, with consequent induction of apoptosis. In particular, we demonstrate that the mechanism controlling FasL up-regulation is ascribed principally to GXM/FcγRIIB interaction and is mediated by activation of JNK, p38 and c-Jun. JNK and p38 are activated independently, but both induce c-Jun activation. In addition, activation of c-Jun is regulated by FcγRIIB; therefore, FasL overexpression is dependent, at least in part, on c-Jun activation. These observations are supported by recent studies showing that FcγRIIB engagement induces phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic molecule JNK [40]. However, no evidence has yet been provided that FcγRIIB is involved in regulation of FasL expression. The processes that regulate FasL up-regulation were, in fact, largely unknown. Here we report for the first time that there is a direct relationship between FcγRIIB and FasL regulation. Indeed, a proteolytic release of FasL from the cellular membrane has already been documented [41], thus the possibility arises that soluble FasL could be generated during GXM stimulation. The shedding of FasL could account for the relative difficulty in detecting a strong increase in the percentage of FasL-positive cells.We cannot exclude the possibility that additional cellular receptors such as TLR-2, TLR-4, CD14 and CD18, which are exploited by GXM, might participate in the activation of JNK and p38 and, as a consequence, may also contribute to FasL up-regulation. This is conceivable for three reasons. First, an involvement of TLR in JNK and p38 phosphorylation has been reported [42,43]. Secondly, activation of JNK and p38 is crucial for the up-regulation of FasL, as demonstrated by the effect of pharmacological inhibitors of both JNK and p38 MAPK. Finally, we have demonstrated previously that multiple receptors such as TLR-4, CD14 and CD18 are possibly involved in GXM-mediated FasL up-regulation [12]. Therefore, it is conceivable that the signal pathway that involves Myd88 with consequent activation of p38 and c-Jun contributes to up-regulation of FasL. In this paper, however, it is reported that FcγRII did not seem to be involved in this phenomenon [12]. This apparent discrepancy is due probably to the use of different experimental conditions. In particular, the antibody used in the previous paper was specific for FcγRII, which recognizes both FcγRIIA and FcγRIIB. These two isoforms are related closely in structure, but functionally distinct. In the present study we used a specific blocking antibody to FcγRIIB. Moreover, in the present study a different dose of GXM (100 µg/ml versus 50 µg/ml), different types of cells (MonoMac6 cell line versus monocyte-derived macrophages) and different incubation times (2 h versus 2 days) were used.

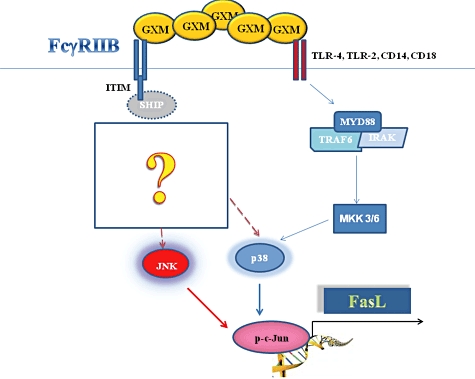

Our previous observations indicated that active SHIP, in cells treated with GXM, was responsible for reduction of NFκB transcriptional activation and negative regulation of inflammatory cytokines. This effect was mediated via GXM/FcγRIIB interaction [17]. The role of SHIP in FasL up-regulation and in GXM-induced apoptosis remains obscure, but we can assume that in our system SHIP activation induced by FcγRIIB engagement plays a direct role in apoptosis induction. Consistent with this hypothesis, early studies have shown a pro-apoptotic role of SHIP1 in several cell types, including B cells, myeloid and erythroid cells [44–46]. Moreover, Liu et al. have reported that myeloid cells from SHIP−/− mice are less susceptible to programmed cell death induced by various apoptotic stimuli via Akt activation [45]. In addition, a substantial amount of literature provides evidence that SHIP1 is required to inhibit Akt activation [45,47–49]. This inhibition is critical for the activation of JNK [50]. Akt negatively regulates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), which activates JNK and p38 transcriptional events [51], therefore inhibition of Akt could lead to ASK activation with consequent phosphorylation of downstream signalling molecules such as JNK and p38. In this study we demonstrated that GXM induces up-regulation of FasL expression by JNK or p38 signalling, which activate c-Jun independently of each other. In particular, JNK activation seems to be a consequence of GXM interaction with FcγRIIB, whereas p38 activation is also triggered by the binding of GXM with different pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). However, the capacity of GXM to engage multiple PRRs, such as TLR-4 and FcgRIIB, which simultaneously transmit activating and inhibitory signals, might justify the high level of complexity of these signalling networks. Indeed, more studies are necessary to unravel the complexity of the GXM-induced signalling pathways. A schematic representation of the proposed pathway is shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of intracellular signalling leading to glucuronoxylomamman (GXM)-mediated Fas ligand (FasL) up-regulation. GXM/FcγRIIB interaction leads to induction of a sequential phosphorylation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 and c-Jun.

Collectively, our results highlight a fast track to FasL up-regulation via FcγRIIB, and provide evidence for a mechanism involved in the activation of JNK, p38 and c-Jun. Moreover, the present study amplifies the spectrum of FcγRIIB-mediated effects, indicating that this receptor plays a critical role in transducing multiple signallings which contribute to inducing suppressive effects on innate and adaptive immunity. Given that GXM has been recovered in the body fluids of patients with cryptococcosis at a concentration similar to that used in our experimental system [52], the induction of GXM-induced T cell apoptosis could exacerbate the immunosuppressive status of patients. In this context, facilitation of the clearance of GXM by treatment with protective antibodies [53] could limit the deleterious effect produced by soluble GXM. These results highlight a novel mechanism of immunosuppression which partly explains the dysregulation of immune responses accompanying cryptococcal infection.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the European Commission: FINSysB Marie Curie Initial Training 16 Network, PITN-GA-2008-214004; and the National Health Institute: SPAL09AVEC. We thank Catherine Macpherson for editorial assistance.

Disclosure

There are no financial and commercial conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Tzianabos AO. Polysaccharide immunomodulators as therapeutic agents: structural aspects and biologic function. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:523–33. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.523-533.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vecchiarelli A. Fungal capsular polysaccharide and T-cell suppression: the hidden nature of poor immunogenicity. Crit Rev Immunol. 2007;27:547–57. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i6.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monari C, Kozel TR, Casadevall A, Pietrella D, Palazzetti B, Vecchiarelli A. B7 costimulatory ligand regulates development of the T-cell response to Cryptococcus neoformans. Immunology. 1999;98:27–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrella D, Monari C, Retini C, Palazzetti B, Kozel TR, Vecchiarelli A. HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp120 induces development of a T helper type 2 response to Cryptococcus neoformans. AIDS. 1999;13:2197–207. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199911120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vecchiarelli A, Pietrella D, Lupo P, Bistoni F, McFadden DC, Casadevall A. The polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans interferes with human dendritic cell maturation and activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:370–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Pietrella D, et al. Downregulation by cryptococcal polysaccharide of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1 beta secretion from human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2919–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2919-2923.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Monari C, Tascini C, Bistoni F, Kozel TR. Purified capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans induces interleukin-10 secretion by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2846–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2846-2849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Retini C, Kozel TR, Pietrella D, Monari C, Bistoni F, Vecchiarelli A. Interdependency of interleukin-10 and interleukin-12 in regulation of T-cell differentiation and effector function of monocytes in response to stimulation with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6064–73. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6064-6073.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syme RM, Bruno TF, Kozel TR, Mody CH. The capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans reduces T-lymphocyte proliferation by reducing phagocytosis, which can be restored with anticapsular antibody. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4620–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4620-4627.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retini C, Vecchiarelli A, Monari C, Bistoni F, Kozel TR. Encapsulation of Cryptococcus neoformans with glucuronoxylomannan inhibits the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:664–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.664-669.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retini C, Casadevall A, Pietrella D, Monari C, Palazzetti B, Vecchiarelli A. Specific activated T cells regulate IL-12 production by human monocytes stimulated with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 1999;162:1618–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monari C, Pericolini E, Bistoni G, Casadevall A, Kozel TR, Vecchiarelli A. Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan induces expression of fas ligand in macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174:3461–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monari C, Paganelli F, Bistoni F, Kozel TR, Vecchiarelli A. Capsular polysaccharide induction of apoptosis by intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2129–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monari C, Bevilacqua S, Piccioni M, et al. A microbial polysaccharide reduces the severity of rheumatoid arthritis by influencing Th17 differentiation and proinflammatory cytokines production. J Immunol. 2009;183:191–200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monari C, Bistoni F, Casadevall A, et al. Glucuronoxylomannan, a microbial compound, regulates expression of costimulatory molecules and production of cytokines in macrophages. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:127–37. doi: 10.1086/426511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monari C, Bistoni F, Vecchiarelli A. Glucuronoxylomannan exhibits potent immunosuppressive properties. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:537–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monari C, Kozel TR, Paganelli F, et al. Microbial immune suppression mediated by direct engagement of inhibitory Fc receptor. J Immunol. 2006;177:6842–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turjanski AG, Vaque JP, Gutkind JS. MAP kinases and the control of nuclear events. Oncogene. 2007;26:3240–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Thiel E, Futterer A, Herzog V, Wirtz A, Riethmuller G. Establishment of a human cell line (Mono Mac 6) with characteristics of mature monocytes. Int J Cancer. 1988;41:456–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cherniak R, Reiss E, Slodki ME, Plattner RD, Blumer SO. Structure and antigenic activity of the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A. Mol Immunol. 1980;17:1025–32. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(80)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houpt DC, Pfrommer GS, Young BJ, Larson TA, Kozel TR. Occurrences, immunoglobulin classes, and biological activities of antibodies in normal human serum that are reactive with Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2857–64. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2857-2864.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vecchiarelli A, Dottorini M, Pietrella D, et al. Role of human alveolar macrophages as antigen-presenting cells in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:130–7. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.2.8049074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, Keehnen RM, Pals ST, van Oers MH. Annexin V for flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on B cells undergoing apoptosis. Blood. 1994;84:1415–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccardi C, Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1458–61. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migliorati G, Nicoletti I, Pagliacci MC, D'Adamio L, Riccardi C. Interleukin-4 protects double-negative and CD4 single-positive thymocytes from dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Blood. 1993;81:1352–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eng RH, Bishburg E, Smith SM, Kapila R. Cryptococcal infections in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1986;81:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu SC, Gavrilin MA, Tsai MH, Han J, Lai MZ. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is involved in Fas ligand expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25769–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, et al. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19245–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhanasekaran DN, Reddy EP. JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6245–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JC, Kassis S, Kumar S, Badger A, Adams JL. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors – mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;82:389–97. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene. 2001;20:2390–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazzalin CA, Cano E, Cuenda A, Barratt MJ, Cohen P, Mahadevan LC. p38/RK is essential for stress-induced nuclear responses: JNK/SAPKs and c-Jun/ATF-2 phosphorylation are insufficient. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1028–31. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tibbles LA, Woodgett JR. The stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:1230–54. doi: 10.1007/s000180050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smelcerovic A, Knezevic-Jugovic Z, Petronijevic Z. Microbial polysaccharides and their derivatives as current and prospective pharmaceuticals. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:3168–95. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravetch JV, Lanier LL. Immune inhibitory receptors. Science. 2000;290:84–9. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura A, Takai T. A role of FcgammaRIIB in the development of collagen-induced arthritis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2004;58:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGaha TL, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV. FcgammaRIIB deficiency leads to autoimmunity and a defective response to apoptosis in Mrl–MpJ mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:5670–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang G, Gong P, Xu L, et al. Inhibitory receptor FcGRIIB is overexpressed, and its ligation by anti-FcGRIIB antibodies suppresses IgM production and induces apoptosis in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. 2009. 51st ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, New Orleans, USA.

- 41.Schulte M, Reiss K, Lettau M, et al. ADAM10 regulates FasL cell surface expression and modulates FasL-induced cytotoxicity and activation-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1040–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rincon M, Davis RJ. Regulation of the immune response by stress-activated protein kinases. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:212–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brauweiler A, Tamir I, Dal Porto J, et al. Differential regulation of B cell development, activation, and death by the src homology 2 domain-containing 5′ inositol phosphatase (SHIP) J Exp Med. 2000;191:1545–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Q, Sasaki T, Kozieradzki I, et al. SHIP is a negative regulator of growth factor receptor-mediated PKB/Akt activation and myeloid cell survival. Genes Dev. 1999;13:786–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boer AK, Drayer AL, Vellenga E. Effects of overexpression of the SH2-containing inositol phosphatase SHIP on proliferation and apoptosis of erythroid AS-E2 cells. Leukemia. 2001;15:1750–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalesnikoff J, Sly LM, Hughes MR, et al. The role of SHIP in cytokine-induced signaling. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;149:87–103. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerezo A, Martinez AC, Lanzarot D, Fischer S, Franke TF, Rebollo A. Role of Akt and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 in apoptosis induced by interleukin-4 deprivation. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3107–18. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levresse V, Butterfield L, Zentrich E, Heasley LE. Akt negatively regulates the cJun N-terminal kinase pathway in PC12 cells. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:799–808. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001215)62:6<799::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suhara T, Kim HS, Kirshenbaum LA, Walsh K. Suppression of Akt signaling induces Fas ligand expression: involvement of caspase and Jun kinase activation in Akt-mediated Fas ligand regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:680–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.680-691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim AH, Khursigara G, Sun X, Franke TF, Chao MV. Akt phosphorylates and negatively regulates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:893–901. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.893-901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monari C, Retini C, Casadevall A, et al. Differences in outcome of the interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan and human monocytes and neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1041–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casadevall A, Pirofski L. Insights into mechanisms of antibody-mediated immunity from studies with Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:421–33. doi: 10.2174/1566524054022567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]