Abstract

Background

Overweight and obesity are substantial problems in the U.S., but few national studies exist on primary care physicians’ (PCPs) clinical practices regarding overweight and obesity.

Purpose

To profile diet, physical activity and weight control practice patterns of PCPs who treat adults.

Methods

A nationally representative survey of 1,211 PCPs sampled from the American Medical Association’s Masterfile was conducted in 2008 and analyzed in 2010. Outcomes included: PCPs’ assessment, counseling, referral, and follow-up of diet, physical activity and weight control in adult patients with and without chronic disease; PCPs’ use of pharmacologic treatments and surgical referrals for overweight and obesity.

Results

The survey response rate was 64.5%. Half of PCPs (49%) reported recording BMI regularly. Fewer than 50% reported always providing specific guidance on diet, physical activity, or weight control. Regardless of patients’ chronic disease status, <10% of PCPs always referred patients for further evaluation/management, and <22% reported always systematically tracking patients over time concerning weight or weight-related behaviors. Overall, PCPs were more likely to counsel on physical activity than on diet or weight control (ps<0.05). More than 70% of PCPs reported ever using pharmacologic treatments to treat overweight and 86% had referred for obesity-related surgery.

Conclusions

PCPs’ assessment and behavioral management of overweight and obesity in adults is at a low level relative to the magnitude of the problem in the U.S.

Introduction

Managing obesity is one of the biggest health challenges facing healthcare providers today, as almost 70% of the adult population in the U.S. is now considered overweight or obese.1 Obesity increases risks of many medical conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and some cancers, as well as total morbidity and mortality.2,3 Poor diet and physical inactivity increase the risk of obesity. Yet, data show that approximately 60% of the U.S. adult population gets insufficient regular physical activity4 and that few Americans are consuming diets consistent with guidelines.5 To combat the epidemic of overweight and obesity, research on clinical practices related to “energy balance,” (i.e., regulating energy intake (diet) and expenditure (physical activity) for healthy weight), has recently increased.2,3, 6–20

Research consistently documents that physician recommendations have a strong influence on individual health behaviors, and that physicians are an important source of information on preventive healthcare.14,17 Evidence also suggests that physician recommendations are associated with patient efforts to increase physical activity8 and to lose weight.11 Further, current clinical guidelines support the need for healthcare providers to identify and treat overweight/obesity.3 However, studies that have examined primary care physicians’ (PCPs’) counseling practices regarding preventive care show patterns of relatively low emphasis on general prevention, and on weight control, nutrition, or exercise counseling.6,7, 9,10, 12,13, 15,16, 18, 20 These data suggest a need to better understand physicians’ energy-balance clinical practices, such as counseling for diet, physical activity and weight control, particularly given their relationship to disease burden. To date, no national U.S. surveys have comprehensively examined PCPs’ assessment, counseling and follow-up of patients’ diet, physical activity, and weight. To address these gaps, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the NIH, developed the National Survey of Energy Balance Related Care among Primary Care Physicians (EB-PCP), with cosponsorship from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and the CDC. This survey is the first to specifically examine four primary care specialties and to address differences in practice among clinicians treating adults with and without weight-related chronic illness and clinicians treating children. Given major recent health policy changes and the shifting healthcare landscape, this survey provides baseline information to better understand the influence of healthcare reform policies. For example, screening for overweight and obesity is a public health priority and is a Healthy People 2020 objective.21 This survey will inform this objective and better identify subgroups of physicians who could be targets for interventions to increase routine energy-balance clinical practices.

The overall goal was to obtain nationally representative data on PCPs’ use of energy-balance clinical practices, defined as: risk-assessment, counseling, follow-up, and referral patterns, and to identify characteristics of physicians who routinely incorporate these practices in patient care.

Methods

Sample Design

The EB-PCP survey target population was non-Federal, office-based, actively practicing PCPs in the U.S. Physicians were selected from the following primary care specialties: family practice (FP), internal medicine (IM), obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN) and pediatrics (PEDS). A systematic stratified sample of PCPs was obtained using the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physician Masterfile as the sampling frame. The Masterfile contains demographic and practice-related data on all allopathic and most osteopathic physicians in the U.S.22 Eligible respondents were aged ≤75 years with an active medical license who provided at least 20 hours of patient care per week. Additional information on sample selection, survey fielding, and honorarium is in Appendix A (available online at www.ajpm-online.net).

Survey Instruments and Survey Yields

The EB-PCP survey consisted of three questionnaires: two versions of a physician questionnaire and a separate questionnaire focusing on the physician’s practice environment. One version of the physician questionnaire was tailored to PCPs who treat adults, and one for PCPs who treat children. Each took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Data for this analysis are derived from the adult version of the physician questionnaire, plus two items from the questionnaire on the physicians’ practice environment. The full questionnaires can be obtained from the NCI website.23 This paper presents data about PCPs’ energy-balance clinical practices: general counseling, specific guidance, referral, tracking patients, risk assessment, and pharmacologic/surgical treatments. Descriptions of the questions are provided in Appendix B (available online at www.ajpm-online.net). Each question was asked twice, once in relation to “adult patients without weight-related chronic disease who have an unhealthy diet, are insufficiently active, or are overweight” and again for “adult patients with weight-related chronic disease who have an unhealthy diet, are insufficiently active, or are overweight.”

PCPs’ background characteristics (specialty, years since medical school, graduation from an international medical school, board certification, and census region) were obtained from the AMA Masterfile. Demographic information (age, race/ethnicity, gender), and the patient population that he/she treated were obtained from the physician questionnaire. Information on the practice urbanicity, type (single/multi-specialty), and percentage of patients in managed care were obtained from the practice environment questionnaire.

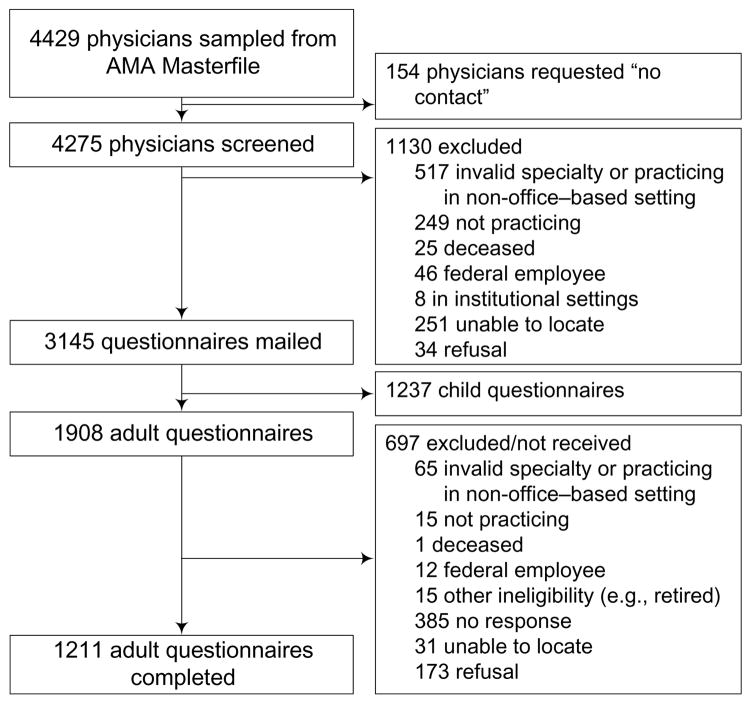

Data collection was from March–December 2008 and data were analyzed in 2010. For the entire survey (adult and child), 4,429 physicians were drawn from the AMA file and 3,145 questionnaires were mailed. A total of 2,027 questionnaires were completed. Figure 1 shows survey yields for the adult version of the questionnaire, 1,908 were mailed and 1,211 were completed (IM: n=403, OB/GYN: n=420, FP: n=388).

Figure 1.

Survey yields and data collection

Note: AMA, American Medical Association

Data Analysis

Sample weights were developed to compensate for differential selection probabilities, nonresponse, and undercoverage of the target population. For variance estimation, replicate weights were generated using the Jackknife replication method24 and used SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 10.0)25 for analyses. Frequency tables compare the distribution of the PCPs’ energy-balance clinical practices by PCP specialty. Chi-square tests were conducted to test for independent associations between PCP specialty and energy-balance clinical practices.

Ordinal logistic regressions were conducted to examine relationships between background characteristics and the frequency of PCPs’ counseling, follow-up and referral practices. Ordinal logistic regression models were chosen because of the ordinal nature of the scaled variables. The proportional odds assumption of these models was examined using standard methods comparing ordinal models to corresponding binary models,26 and confirmed that the proportional odds assumption was met. Covariates included in the final models were specialty, years since medical school (an alternative to age), PCPs’ gender, race/ethnicity, Census region, and practice urbanicity. Two-way interactions of PCP and patient characteristics were examined but were excluded from the final models because none were significant. To preserve sample size and reduce potential bias, missing values for each covariate were treated as a separate category in analyses, and were not interpreted in the results. For the risk-assessment practices (assessment of diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and body size), only univariate tests were performed, due to small cell sizes.

To further investigate PCPs’ specific guidance practices, pair-wise likelihood tests among the three topic areas (diet, physical activity, and weight control) were conducted using t-statistics to test for significance. For each topic area, one binary logistic regression model (Always + Often versus all other levels) was estimated and the likelihood of each counseling practice was computed as the predicted probabilities from the corresponding logistic regression model.

Finally, binary logistic regression analyses were used to examine PCPs’ reported use of pharmaceutic treatments (Yes/No) and referrals for surgical procedures for weight control (Yes/No). Covariates were specialty, years since medical school, and PCPs’ gender, race/ethnicity, Census region, and practice urbanicity.

Results

The response rate for the entire EB-PCP survey was 64.5%. For the adult-focused questionnaire, response rates by specialty were: IM=63.0%, OB/GYN=66.1%, FP=64.2%. The cooperation rate (excluding PCPs listed as “no-contact” by the AMA and those for whom we did not have valid contact information) was 69.8%. The response and cooperation rates were calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research RR3 and COOPR3 formulas.27 The majority of respondents were non-Hispanic white, male, and the mean age was 49 years. PCPs’ demographic and background characteristics are in Appendix C (available online at www.ajpm-online.net).

Appendix D (available online at www.ajpm-online.net) presents frequencies of PCPs’ provision of energy-balance clinical practices including general counseling, specific guidance on diet, physical activity, and weight control; referral for further evaluation/management of diet, physical activity and weight control; and systematic tracking/follow-up, for adult patients with and without chronic disease. PCPs in all specialties were less likely to report “always” providing specific guidance to their patients without weight-related chronic disease (21%–30%) than to those with weight-related chronic disease (39%–49%). However, less than 10% reported “always” referring their patients (even those with chronic disease) for further evaluation/management. Approximately half of PCPs reported “always” providing general counseling and physical activity-specific guidance to their patients with weight-related disease, with fewer reporting specific guidance on diet (43.4%) or weight control (38.7%). Similar patterns were seen for PCPs’ counseling of patients without chronic disease. Significantly more IMs reported “always” providing general counseling compared with other specialties (Appendix D, available online at www.ajpm-online.net). These relationships were largely confirmed by multivariate logistic regression models presented in Table 1. Models indicated that specialty had significant associations with counseling and systematic tracking of patients on diet, physical activity, weight, (all ps<0.0001), after adjusting for other variables. For patients without chronic disease, OB/GYNs were less likely than IMs to provide general counseling and specific guidance, and both OB/GYNs and FPs were less likely than IMs to systematically track patients on weight-related issues. For patients with chronic disease, both OB/GYNs and FPs less frequently reported providing general counseling, specific guidance, or systematically tracking patients than did IMs. Female physicians were more likely than male physicians to provide general counseling or specific guidance on diet to all patients, and to refer patients with chronic disease for further evaluation and management (ps<0.01). Asian American and Hispanic physicians, and physicians in large cities were more likely than other physicians to provide general counseling or specific guidance (ps<0.05). In general, PCPs who were out of medical school longer were more likely than recent graduates (<10 years) to provide energy-balance clinical practices. Physicians in the South less often reported providing general or specific guidance to adults without chronic disease and referrals for all patients. Likelihood test results indicated that all PCPs were more likely to often or always provide counseling on physical activity than on diet or weight control (predicted probabilities = 0.85, 0.77, and 0.69, respectively, ps<0.05 for all pair-wise differences).

Table 1.

Characteristics associated with counseling, referral, and follow-up practices for adult patients a

| Provide general counseling | Provide specific guidance on diet/nutrition | Provide specific guidance on physical activity | Provide specific guidance on weight control | Refer patients for further evaluation and management | Systematically track/follow patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Characteristics | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | OR (CI) | OR (CI) |

| Patients without chronic disease

| ||||||

| Primary specialty | ||||||

| Internal Medicine | 1.00 (REF) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Family Practice | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | 0.99 (0.73, 1.34) | 0.85 (0.62, 1.17) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.05) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25) | 0.57 (0.41, 0.79)** |

| OB/GYN | 0.42 (0.32,0.55)*** | 0.61 (0.46, 0.82)** | 0.46 (0.34, 0.64)*** | 0.43 (0.32, 0.57)*** | 1.41 (0.96, 2.08) | 0.18 (0.12, 0.25)*** |

| Years since medical school | ||||||

| <10 years | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 11–20 years | 1.19 (0.83, 1.72) | 1.53 (1.02, 2.28)* | 1.36 (0.91, 2.03) | 1.64 (1.04, 2.59)* | 0.79 (0.50, 1.24) | 1.21 (0.81, 1.82) |

| 21–30 years | 1.49 (1.02, 2.19)* | 1.71 (1.19, 2.48)** | 1.61 (1.11, 2.34)* | 1.66 (1.08, 2.55)* | 0.78 (0.48, 1.29) | 1.78 (1.20, 2.64)** |

| >30 years | 1.36 (0.85, 2.17) | 1.76 (1.10, 2.81)* | 1.62 (1.00, 2.63) | 2.44 (1.50, 3.98)*** | 0.90 (0.57, 1.42) | 2.28 (1.49, 3.50)*** |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | 1.45 (1.09, 1.93)* | 1.54 (1.17, 2.02)** | 1.06 (0.79, 1.43) | 1.05 (0.78, 1.42) | 1.40 (1.02, 1.94)* | 1.26 (0.95, 1.66) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White/non-Hispanic | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American/non-Hispanic | 1.69 (0.96, 2.99) | 1.17 (0.72, 1.92) | 0.92 (0.56, 1.51) | 1.33 (0.88, 2.01) | 1.05 (0.46, 2.36) | 1.23 (0.79, 1.90) |

| Asian American, non-Hispanic | 1.24 (0.88, 1.74) | 1.92 (1.35, 2.72)*** | 1.81 (1.27, 2.58)** | 1.86 (1.29, 2.68)** | 0.94 (0.58, 1.51) | 1.15 (0.74, 1.78) |

| Hispanic | 1.99 (1.15, 3.44)* | 2.15 (1.17, 3.95)* | 1.88 (1.13, 3.13)* | 3.27 (1.85, 5.79)*** | 0.95 (0.43, 2.10) | 0.89 (0.43, 1.87) |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Midwest | 0.92 (0.63, 1.35) | 0.83 (0.57, 1.20) | 0.92 (0.65, 1.30) | 1.06 (0.72, 1.56) | 0.91 (0.57, 1.45) | 1.25 (0.88, 1.78) |

| South | 0.65 (0.44, 0.97)* | 0.66 (0.46, 0.94)* | 0.74 (0.51, 1.07) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.24) | 0.58 (0.36, 0.93)* | 0.98 (0.67, 1.44) |

| West | 0.80 (0.54, 1.19) | 0.63 (0.43, 0.92)* | 0.69 (0.44, 1.07) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.07) | 0.95 (0.60, 1.49) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.25) |

| Practice urbanicity | ||||||

| Large city | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Medium city | 0.58 (0.38, 0.90)* | 0.54 (0.36, 0.81)** | 0.59 (0.39, 0.88)* | 0.66 (0.44, 1.01) | 0.70 (0.44, 1.12) | 0.66 (0.44, 0.99)* |

| Small city | 0.73 (0.49, 1.07) | 0.59 (0.40, 0.86)** | 0.73 (0.50, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.69, 1.48) | 0.77 (0.49, 1.19) | 0.83 (0.56, 1.23) |

| Rural | 0.69 (0.43, 1.11) | 0.56 (0.34, 0.93)* | 0.54 (0.33, 0.89)* | 0.73 (0.47, 1.16) | 0.49 (0.24, 0.98)* | 0.84 (0.49, 1.43) |

|

| ||||||

| Patients with chronic disease

| ||||||

| Primary specialty | ||||||

| Internal Medicine | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Family Practice | 0.66 (0.49, 0.89)** | 0.73 (0.55, 0.98)* | 0.67 (0.49, 0.92)* | 0.69 (0.52, 0.92)* | 1.08 (0.78, 1.47) | 0.67 (0.51, 0.90)** |

| OB/GYN | 0.26 (0.19, 0.36)*** | 0.29 (0.21, 0.40)*** | 0.26 (0.19, 0.37)*** | 0.27 (0.20, 0.37)*** | 1.17 (0.87, 1.57) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.18)*** |

| Years since medical school | ||||||

| <10 years | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 11–20 years | 1.26 (0.85, 1.86) | 1.67 (1.13, 2.47)* | 1.34 (0.90, 1.98) | 1.34 (0.92, 1.94) | 1.05 (0.72, 1.53) | 1.39 (0.91, 2.13) |

| 21–30 years | 1.39 (0.95, 2.04) | 1.50 (1.02, 2.21)* | 1.41 (0.99, 2.03) | 1.51 (1.02, 2.23)* | 0.91 (0.61, 1.36) | 1.75 (1.24, 2.47)** |

| >30 years | 1.33 (0.83, 2.11) | 1.22 (0.75, 1.98) | 1.34 (0.83, 2.16) | 1.82 (1.18, 2.79)** | 0.90 (0.61, 1.32) | 1.94 (1.26, 2.97)** |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Female | 1.39 (1.04, 1.86)* | 1.29 (0.98, 1.69) | 1.17 (0.88, 1.55) | 1.06 (0.82, 1.38) | 1.47 (1.10, 1.97)** | 1.15 (0.86, 1.53) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White/non-Hispanic | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| African American/non-Hispanic | 1.24 (0.65, 2.36) | 1.80 (1.02, 3.17)* | 1.19 (0.67, 2.11) | 1.26 (0.71, 2.26) | 1.15 (0.64, 2.06) | 1.27 (0.77, 2.10) |

| Asian American/non-Hispanic | 1.63 (1.18, 2.25)** | 1.92 (1.40, 2.63)*** | 1.87 (1.32, 2.66)*** | 2.58 (1.86, 3.58)*** | 1.33 (0.96, 1.85) | 1.25 (0.88, 1.78) |

| Hispanic | 3.84 (1.74, 8.47)** | 3.96 (1.97, 7.93)*** | 4.02 (1.83, 8.85)*** | 3.01 (1.24, 7.34)* | 1.26 (0.66, 2.41) | 1.22 (0.63, 2.39) |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Midwest | 0.94 (0.63, 1.39) | 0.89 (0.62, 1.29) | 0.98 (0.68, 1.43) | 1.09 (0.74, 1.62) | 0.64 (0.45, 0.91)* | 1.03 (0.72, 1.47) |

| South | 0.92 (0.62, 1.37) | 0.87 (0.60, 1.24) | 0.89 (0.62, 1.28) | 0.96 (0.67, 1.37) | 0.46 (0.33, 0.65)*** | 0.92 (0.65, 1.30) |

| West | 0.90 (0.57, 1.43) | 0.89 (0.59, 1.33) | 0.92 (0.62, 1.37) | 0.76 (0.50, 1.16) | 0.72 (0.52, 1.01) | 0.68 (0.45, 1.02) |

| Practice urbanicity | ||||||

| Large city | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Medium city | 0.74 (0.47, 1.17) | 0.61 (0.39, 0.95)* | 0.65 (0.40, 1.06) | 0.73 (0.47, 1.12) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.03) |

| Small city | 1.05 (0.75, 1.47) | 0.83 (0.59, 1.17) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.26) | 0.95 (0.69, 1.33) | 0.88 (0.61, 1.26) | 0.92 (0.64, 1.31) |

| Rural | 1.02 (0.65, 1.61) | 0.62 (0.39, 0.97)* | 0.66 (0.41, 1.05) | 0.74 (0.48, 1.13) | 0.64 (0.39, 1.05) | 0.86 (0.54, 1.38) |

Each model includes the following covariates: physician primary specialty, physicians’ years since medical school, physician gender, physician race/ethnicity, Census region, and practice urbanicity.

p<0.05.

p <0.01.

p < 0.001

Table 2 shows the frequency of PCPs’ assessment of diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and body size. More than 80.0% of PCPs reported some assessment of food intake and amount of physical activity; 64% reported assessing sedentary activities. A greater percentage of OB/GYNs reported no assessment of diet (19.0% vs 5.5%–6.7% of other specialties), no assessment of physical activity (8.6% vs 2.8% of other specialties), and no assessment of sedentary behavior (52.2% vs 36.7% of IMs and 27.8% of FPs). Detailed measurements of diet and physical activity using standardized questionnaires were rare regardless of specialty (<12.0%). Almost all PCPs (95.2%) reported measuring body weight regularly, although fewer (48.7%) regularly reported BMI assessment. FPs were most likely to report regular BMI assessment compared to other specialties (55.1% vs 46.4% of IMs and 38.7% of OB/GYNs, p<0.001). Regular assessment of waist or hip circumferences, or recording of patient self-reported weight was rare in all specialties.

Table 2.

Univariate associations for diet, physical activity, and weight status/body size assessment behaviors by primary care specialty

| Total N=1,211 | Internal Medicine n=403 | Family Practice n=388 | OB/GYN n=420 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Diet a | |||||

| Standardized diet questionnaire | 135 (11.1) | 53 (13.2) | 58 (11.9) | 24 (5.7) | <0.01 |

| General questions about food groups | 985 (81.3) | 350 (86.8) | 332 (68.0) | 303 (72.1) | <0.05 |

| General questions about dietary patterns | 1020 (84.2) | 362 (89.8) | 349 (71.5) | 309 (73.4) | <0.001 |

| Specific questions about diet components | 764 (63.1) | 266 (66.0) | 250 (51.2) | 248 (59.0) | 0.864 |

| Other (written in) assessment | 159 (13.1) | 63 (15.6) | 65 (13.3) | 31 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| I do not assess diet | 134 (11.1) | 27 (6.7) | 27 (5.5) | 80 (19.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity a | |||||

| Standardized physical activity questionnaire | 85 (7.0) | 40 (9.9) | 33 (6.8) | 12 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| General questions about amount of physical activity | 1142 (94.3) | 389 (96.5) | 373 (76.4) | 380 (90.3) | 0.087 |

| Specific questions about duration, intensity, type of physical activity | 991 (81.8) | 352 (87.3) | 344 (70.5) | 295 (70.1) | <0.001 |

| Other (written in) assessment | 51 (4.2) | 25 (6.2) | 19 (3.8) | 7 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| I do not assess physical activity | 57 (4.7) | 10 (2.5) | 11 (2.3) | 36 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Sedentary behavior | |||||

| I do assess | 697 (64.4) | 245 (63.2) | 270 (72.2) | 182 (47.8) | <0.001 |

| Weight measured on scale in office | |||||

| Regularly b | 1156 (95.2) | 378 (94.0) | 369 (95.1) | 409 (97.4) | 0.19 |

| As clinically indicated | 46 (4.2) | 20 (5.0) | 15 (4.3) | 11 (2.6) | |

| Never | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Weight measured by patient self-report | |||||

| Regularly b | 177 (15.9) | 86 (22.4) | 43 (11.8) | 48 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| As clinically indicated | 407 (38.0) | 146 (37.7) | 154 (43.2) | 107 (27.2) | |

| Never | 550 (45.3) | 150 (38.6) | 161 (44.3) | 239 (60.4) | |

| Other | 8 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Height measured in office | |||||

| Regularly b | 908 (77.0) | 299 (74.5) | 316 (81.9) | 293 (70.9) | <0.001 |

| As clinically indicated | 214 (17.6) | 78 (19.6) | 61 (15.8) | 75 (17.7) | |

| Never | 56 (3.5) | 15 (3.9) | 4 (1.0) | 37 (8.6) | |

| Other | 25 (1.8) | 8 (2.0) | 5 (1.3) | 12 (2.8) | |

| BMI | <0.001 | ||||

| Regularly b | 554 (48.7) | 186 (46.4) | 209 (55.1) | 159 (38.7) | |

| As clinically indicated | 457 (38.0) | 158 (39.0) | 148 (37.8) | 151 (36.3) | |

| Never | 180 (12.3) | 54 (13.8) | 23 (5.6) | 103 (24.5) | |

| Other | 10 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Waist circumference | <0.001 | ||||

| Regularly b | 72 (6.5) | 33 (8.3) | 26 (6.4) | 13 (3.1) | |

| As clinically indicated | 327 (31.2) | 133 (33.5) | 137 (36.8) | 57 (14.4) | |

| Never | 787 (61.5) | 227 (57.2) | 217 (55.9) | 343 (82.3) | |

| Other | 8 (0.8) | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | |

Diet and physical activity assessment categories are not mutually exclusive.

Body size assessments are mutually exclusive. “Regularly” = every well-patient visit, every visit, and annually.

Finally, a high prevalence was observed of PCPs’ ever-using pharmacologic treatments for weight control (71.2%) and ever-referring for surgical treatments for obesity (86.0%). OB/GYNs were less likely to prescribe weight-loss medications than IMs (43.7% vs 73.6%; OR=0.23, 95% CI=0.18, 0.35), while the difference between IMs and FPs was not significant (73.6% vs 81.4%; OR=1.34, 95% CI=0.90, 2.00). Compared to IMs, OB/GYNs also were less likely to refer patients for surgical procedures for obesity (86.7% vs 73.8%; OR=0.37, 95% CI=0.24, 0.55), with no significant difference between IMs and FPs (86.7% vs 90.9%; OR=1.15, 95% CI=0.70, 1.91). Female and Asian physicians (compared to male and white physicians), as well as those longer from medical school, were less likely to prescribe medications. Asian physicians were also less likely than white physicians to refer for surgical treatments.

Discussion

This study provides nationally representative data describing energy-balance clinical practices among U.S. PCPs regarding their adult patients’ diet, physical activity, and weight control. Results suggest that PCPs’ energy-balance clinical practice is fairly low and needs improvement. While the majority of PCPs report regularly assessing weight and height, less than half are converting that information into BMI. Similarly, while most PCPs report providing some kind of counseling, less than half always provide specific guidance, even for patients who have weight-related chronic conditions. Few PCPs consistently refer patients for further management or systematically track these behaviors over time, although more PCPs provide care and management for patients with chronic disease than those without. However, almost three quarters of physicians report ever prescribing pharmacologic treatments for weight control and even more (almost 90%) report having ever referred a patient for surgical procedures for obesity. These data track with increases in surgery and drug treatments seen in national studies28,29. Taken together, the current data, although consistent with prior research6, 9,10, 12,13, 15, 18, suggest a need to understand reasons for low levels of energy-balance clinical practices in primary care settings.

Clinical guidelines3, 30,31 and the Surgeon General19,20, emphasize the need for physicians to screen for overweight/obesity. Although NIH guidelines3 provide detailed evidence and guidance for assessing and treating overweight and obesity, and have been endorsed by more than 50 medical and professional groups, PCPs receive mixed messages about counseling on diet and physical activity from other organizations. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and The Task Force on Community Preventive Services, for example, have found insufficient evidence related to the effectiveness of low-level provider-oriented diet and physical activity interventions for obesity or training for such interventions.30–32 The current data suggest that PCPs are not following NIH guidelines, particularly with respect to BMI screening. One possibility is that weight change (not BMI) is used to determine when to counsel about weight, or that PCPs do not want to use BMI defined labels such as obese or overweight with their patients. This may change, as BMI became a required HEDIS measure in 200933, just after the EB-PCP survey was fielded. Future research that documents why physicians are less likely to assess BMI than weight is needed.

In the current study, several factors were associated with PCPs’ clinical practices, and a few were particularly interesting. Consistent with previous research, the current study identified gender34,35 and specialty9, 36 differences. OB/GYNs were least likely to counsel their patients on diet, physical activity, or weight control. One reason may be because they feel they need additional training37. OB/GYNs also were least likely to record BMI, which is concerning, given the focus on BMI in recent guidance on weight gain during pregnancy.38

Irrespective of specialty, all PCPs were more likely to guide patients on physical activity than on diet or weight control, and more likely to provide guidance on diet than weight. This finding also was seen among PCPs who treat children (Huang et al., this issue). It is possible that physical activity is easier to discuss than diet, given the complexity of dietary recommendations and prior research suggests that health professionals are uncomfortable discussing weight or demonstrate weight-based stigmatization toward patients39,40. In the current study PCPs were more likely to intensively manage diet, physical activity, and weight control in patients with chronic disease than those without. Physicians may be concentrating on patients with the greatest problems while missing important prevention opportunities. Previous research has also documented a variety of barriers related to counseling including physician’s perceptions of insufficient skills or training, lack of time, lack of office supports, and perceptions that patients will not be able to change behaviors.15, 41,42 Future analyses from this survey will document whether these are barriers for U.S. physicians. Overall, results from the current analysis suggest that training, assessment and communication tools, and referral options are needed to increase the number of PCPs who routinely include diet and weight control in patient care.

This study has some important strengths and limitations. A notable limitation is the self-reported nature of the data. However, the current results are consistent with research that has examined physician patient discussions of diet, physical activity and weight control from various vantage points, including from the patient’s perspective,6, 11,12 from the physician’s perspective,9,10, 13, 15, 18 and in chart reviews of individual visits.7, 16, 20 Although it is not possible to directly compare the outcomes of these studies, they suggest that regardless of the unit of analysis, physician-initiated energy-balance clinical practice is not happening frequently. Important strengths of this study are that it provides current, nationally representative data derived from a survey with close to a 70% response rate. These data have implications for health policy and needed resources. For example, stronger messages requiring routine BMI assessment are needed, such as the newly enacted BMI HEDIS measure.33 A focus on energy-balance clinical practices in medical school and continuing education training should be considered. Greater linkage between PCPs and providers of ancillary medical services, such as nurses, dietitians, or exercise specialists, may be necessary to increase obesity prevention and treatment services. Improved tools are needed for assessing diet, physical activity, and weight control, as well as specific applications for their use in energy-balance clinical practices. Increased support for electronic medical records may assist clinicians in more readily assessing, tracking, and referring patients. Further, health policy related to payment reform may be needed to support reimbursement for energy-balance clinical practices.

In sum, the EB-PCP study provides an important indicator of current U.S. PCP energy-balance clinical practices in the areas of diet, physical activity and weight control of adult patients. Although most clinicians are providing some care in this area, they have much room for improvement. Additional research is needed to understand factors that influence PCPs’ energy-balance clinical practices. Data from the EB-PCP will be further explored to determine whether personal experiences (e.g., PCPs own diet and exercise behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge of guidelines), professional barriers (e.g., patient load) or external factors (e.g., staffing, reimbursement, practice-level policies and administration) help explain differences in clinical practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this survey was supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Contract No. N02-PC-61301.

We would like to thank the members of the DHHS survey development team:

National Cancer Institute: Ashley Wilder Smith, Steven Clauser, Rachel Ballard-Barbash, Carrie Klabunde, Susan M. Krebs-Smith, Laurel A. Borowski, Emily Dowling, Gordon Willis, Richard Troiano, Audie A. Atienza, Tanya Agurs-Collins, Bill Davis

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Terry Huang

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Mary Horlick, Myrlene Staten, Susan Yanovski

NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research: Deborah Olster

CDC: Beth Tohill, Deborah Galuska, Laura Kettel Khan

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Barbara Wells, Karen Donato

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Iris Mabry-Hernandez

We would also like to thank Richard Lee and James Todd Gibson for programming support.

The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the NIH or the CDC.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among U.S. adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DHHS. The surgeon general’s vision for a healthy and fit nation. DHHS, Office of the Surgeon General; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH and National Heart Lung Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Rockville, MD: DHHS, Public Health Service; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion and CDC. Physical activity and good nutrition: essential elements to prevent chronic disease and obesity. 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krebs Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. J of Nutr. 2010;140(10):1832–1838. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abid A, Galuska D, Khan LK, Gillespie C, Ford ES, Serdula MK. Are healthcare professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? A trend analysis. MedGenMed. 2005;7:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binns HJ, Lanier D, Pace WD, et al. Describing primary care encounters: the Primary Care Network Survey and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:39–47. doi: 10.1370/afm.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calfas KJ, Long BJ, Sallis JF, Wooten WJ, Pratt M, Patrick K. A controlled trial of physician counseling to promote the adoption of physical activity. Prev Med. 1996;25:225–233. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewing GB, Selassie AW, Lopez CH, McCutcheon EP. Self-report of delivery of clinical preventive services by U.S. physicians. Comparing specialty, gender, age, setting of practice, and area of practice. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:62–72. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank E, Wright EH, Serdula MK, Elon LK, Baldwin G. Personal and professional nutrition-related practices of U.S. female physicians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:326–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA. 1999;282:1576–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko JY, Brown DR, Galuska DA, Zhang J, Blanck HM, Ainsworth BE. Weight loss advice U.S. obese adults receive from health care professionals. Prev Med. 2008;47:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottke TE, Foels JK, Hill C, Choi T, Fenderson DA. Nutrition counseling in private practice: attitudes and activities of family physicians. Prev Med. 1984;13:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(84)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreuter MW, Chheda SG, Bull FC. How does physician advice influence patient behavior? Evidence for a priming effect. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:426–433. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546–552. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J, Urizar GG, Jr, Alehegn T, Stafford RS. Diet and physical activity counseling during ambulatory care visits in the U. S. Prev Med. 2004;39:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrella RJ, Lattanzio CN. Does counseling help patients get active? Systematic review of the literature. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:72–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer EH, Frank E, Elon LK, Hertzberg VS, Serdula MK, Galuska DA. Predictors of nutrition counseling behaviors and attitudes in U.S. medical students. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:655–662. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DHHS. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Rockville, MD: DHHS, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma J, Xiao L. Assessment of body mass index and association with adolescent preventive care in U.S. outpatient settings. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:502–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DHHS, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: the road ahead. [Accessed 2011 Jan 18]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Medical Association. [Accessed January 15, 2010];Physician Data Resources: AMA Physician Masterfile. 2006 www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.shtml.

- 23.Outcomes Research Branch National Cancer Institute. [Accessed March 20, 2010]; www.outcomes.cancer.gov/surveys/energy/2010.

- 24.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 10.0. 2008. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee ES, Forthofer RN. Analyzing Complex Survey Data. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standard Definitions-Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis MM, Slish K, Chao C, Cabana MD. National trends in bariatric surgery, 1996 2002. Arch Surg. 2006;141:71–74. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stafford RS, Radley DC. National trends in antiobesity medication use. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1046–1050. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote physical activity: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:205–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: Recommendations and rationale. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guide to Community Preventive Services, CDC. The community guide-obesity prevention. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Committee for Quality Assurance. State of Health Care Quality Report. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank E, Harvey LK. Prevention advice rates of women and men physicians. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:215–219. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329:478–482. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kristeller JL, Hoerr RA. Physician attitudes toward managing obesity: differences among six specialty groups. Prev Med. 1997;26:542–549. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman VH, Laube DW, Hale RW, Williams SB, Power ML, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists and primary care: training during obstetrics–gynecology residency and current practice patterns. Acad Med. 2007;82:602–607. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180556885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen K, Yaktine A, editors. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: physicians’ reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1246–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forman-Hoffman V, Little A, Wahls T. Barriers to obesity management: a pilot study of primary care clinicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kolasa KM, Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(5):502–9. doi: 10.1177/0884533610380057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.