Abstract

BACKGROUND

Since the identification of xenotropic murine leukemia virus–related virus (XMRV) in prostate cancer patients in 2006 and in chronic fatigue syndrome patients in 2009, conflicting findings have been reported regarding its etiologic role in human diseases and prevalence in general populations. In this study, we screened both plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) collected in Africa from blood donors and human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals to gain evidence of XMRV infection in this geographic region.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

A total of 199 plasma samples, 19 PBMNC samples, and 50 culture supernatants from PBMNCs of blood donors from Cameroon found to be infected with HIV-1 and HIV-1 patients from Uganda were screened for XMRV infection using a sensitive nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay.

RESULTS

Using highly sensitive nested PCR or RT-PCR and real-time PCR assays capable of detecting at least 10 copies of XMRV plasmid DNA per reaction, none of the 268 samples tested were found to be XMRV DNA or RNA positive.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results failed to demonstrate the presence of XMRV infection in African blood donors or individuals infected with HIV-1. More studies are needed to understand the prevalence, epidemiology, and geographic distribution of XMRV infection worldwide.

Xenotropic murine leukemia virus–related virus (XMRV), the first gamma retrovirus known to infect humans, was identified in prostate cancer patients in 20061,2 and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) patients in 2009,3 although a causal relationship has not yet been established and several conflicting findings have been reported.4–8 XMRV has also been detected in 3.7% of healthy individuals3 and 4% of non–prostate cancer patients2 in the United States, and approximately 1% of control groups in Germany,6 the United Kingdom,8 and Japan,9 indicating possible widespread yet low-level distribution of the virus.10 Negative findings of XMRV infection could be attributed to restricted geographic distribution of XMRV worldwide and possible genetic variation of this virus.

Similar to human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 (HIV-1), XMRV may be potentially transmitted through sexual contact as semen has been found to be positive for this virus and prostatic acid phosphatase fragments have been shown to enhance infectivity of XMRV in vitro.11 Blood transfusion and intravenous drug use may likely be other transmission modes since both peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) and plasma from XMRV-positive CFS patients are able to infect cells.3 These results highlight the need for studies on blood donors and risk groups with HIV-1 infection who could be co- or superinfected with XMRV. Recently, a German study reported that XMRV could be detected in respiratory secretions.12 It is not clear whether the presence of XMRV in the respiratory tract indicates that the virus can be transmitted by the respiratory route. In general, retroviruses, like HIV-1, are rarely transmitted through respiratory secretions.

The prevalence of XMRV infection in different populations and geographic areas and its implications for human diseases and public health deserve further study. Therefore, we set out to investigate the prevalence of XMRV infection in African individuals by using sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays to test samples previously collected for monitoring HIV-1 infection in Cameroon and Uganda, which are two geographically distinct regions in Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples

A total of 236 plasma samples were tested including 105 HIV-1 antibody–positive samples (by a rapid HIV-1 antibody assay) from blood donors collected from 2006 to 2009 in Cameroon and 94 HIV-1 antibody–positive plasma samples collected in 2005 in Uganda. Thirty-eight percent of the Ugandan subjects were on antiretroviral therapy with a combination pill containing nevirapine, lamivudine (3TC), and either stavudine (D4T) or zidovudine (AZT) and had fully suppressed HIV viral levels (viral load <400 copies/mL).13 Nineteen PBMNC samples from HIV-1-positive blood donors collected in 2007 in Cameroon were also included in the current study. Blood was collected aseptically into an ethylenediaminetetraacetate vacutainer, and PBMNCs and plasma were separated using Ficoll gradient centrifugation. In addition, 50 cell culture supernatants collected from cultured PBMNCs of 50 HIV-1-positive Cameroonian blood donors were screened for infection with both XMRV and HIV-1. All samples tested were from unique donors.

Nucleic acid extraction and amplification

Viral RNA and genomic DNA were extracted from 200 μL of plasma, cell culture supernatants, or PBMNC samples using a virus spin kit (QIAamp MiniElute, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed with a for first-strand synthesis system (SuperScript III, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using 8 μL of viral RNA and random hexamer primer. For amplification of XMRV gag gene, first-round PCR was performed in a 30 μL volume containing 5 μL of cDNA or 200 to 500 ng of genomic DNA, 15 μL of 2× PCR buffer (Extensor Hi-Fidelity ReddyMix PCR Master Mix, ABgen House, Surrey, UK), and 2.5 pmol of each primer (GAG-O-F and GAG-O-R).1 Reaction conditions were as follows: one cycle at 94°C for 5 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 45 seconds; and one cycle at 72°C, 7 minutes. Two microliters of first-round PCR products was added to the second-round PCR with the same reaction conditions as those in the first PCR procedure except that the different primers (GAG-I-F and GAG-I-R) and the annealing temperature of 60°C were used.1 Each PCR run included both XMRV-positive control (XMRV plasmid DNA) and negative control (water). PCR amplification products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and sequenced. Primers for the XMRV env gene (5922F/6273R and 5942F/6200R) and HIV-1 gp41 gene (GP40F1/GP41R1 and GP46F2/GP47R2) have been described previously.11,14 The PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle at 94°C for 5 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C, 45 seconds; and one cycle at 72°C for 7 minutes. To ensure integrity of extracted DNA, human GAPDH gene was amplified using the same PCR primers (hGAPDH-66F and hGAPDH-291R) and conditions published previously.1 In addition, a quantitative (q)PCR was adapted from the article of Schlaberg and coworkers2 to amplify XMRV DNA with one forward primer and two reverse primers within the pol gene of XMRV.

RESULTS

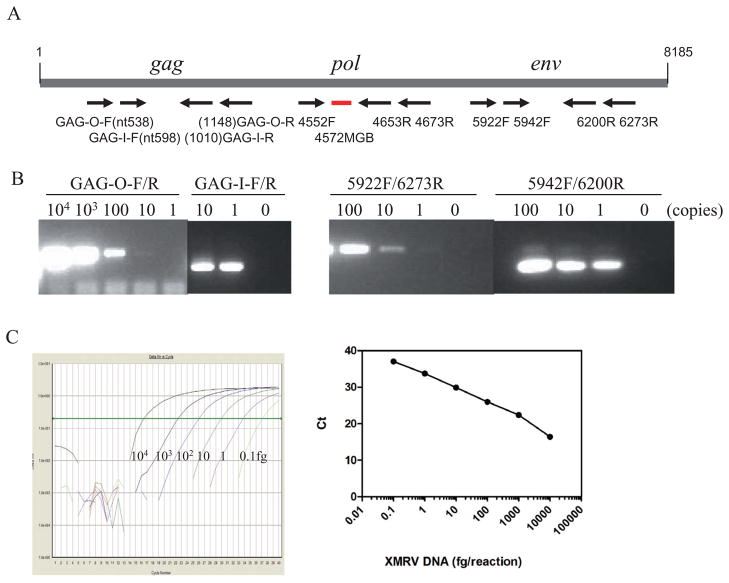

When XMRV plasmid DNA was amplified by both nested PCR and (q)PCR, specific bands with the expected size and (q)PCR curves were observed (Fig. 1). After amplification and analysis of serial 1:10 dilutions of XMRV DNA with known copy numbers based on A260 of the purified plasmid VP62, 10 copies and one copy of plasmid DNA were detected in the first- and second-round PCR, respectively, suggesting a lower detection limit of one copy of proviral DNA using our current nested PCR conditions. The sensitivity of the PCR assays was also evaluated using XMRV DNA extracted from a series of 1:10 dilutions of 22Rv1 cells (CRL-2505, ATCC, Gaithersburg, MD) that harbor multiple copies of integrated XMRV provirus and constitutively produce infectious virus.15 The current nested PCR assay could detect XMRV DNA from single 22Rv1 cells (data not shown). The RT-PCR assay was able to amplify XMRV gag and env genes from cell culture supernatants of 22Rv1 culture with known copy numbers. Our (q)PCR assay could detect 1 to 10 copies of XMRV plasmid DNA, which is comparable to the results reported by Schlaberg and coworkers.2

Fig. 1.

PCR for XMRV detection. (A) Primer sets for nested PCR and (q)PCR are indicated or numbered according to the XMRV vp62 sequence (GenBank Accession Number EF185282). The primer sequences have been previously published.1,2 (B) PCR products. Left panel shows XMRV gag gene products. The first and second PCR products are 612 and 413 nucleotides, respectively. Right panel shows PCR products for XMRV env gene. The first and second PCR products are 325 and 259 nucleotides, respectively. The detection limits of first and second PCR for both XMRV gag and env gene were 10 and 1 copy, respectively. (C) (q)PCR. XMRV plasmid was serially diluted 1:10 from 104 to 0.1 fg and tested. The curves show the sensitivity of the assay, which was 0.1 fg or 6.7 copies in this experiment.

Viral RNA in the plasma samples was used to amplify both XMRV and HIV-1 sequences. HIV-1 RNA was detected in 51% (54/105) and 52% (49/94) of plasma samples from Cameroon and Uganda, respectively (Table 1). However, none of the 199 plasma samples and 50 PBMNC culture supernatants were positive for XMRV RNA using either the gag or the env primer sets of XMRV although the positive control was successfully amplified in each PCR run (Fig. 2A). Genomic DNA from PBMNCs of 19 HIV-1-infected Cameroonian blood donors was also tested but found to be negative for XMRV using both nested PCR and (q)PCR assays (Fig. 2B and Table 1). Among them, 42% (8/19) were positive for HIV-1 RNA. A specific hGAPDH gene was amplified from all 19 samples (Fig. 2B). All of the 50 PBMNC culture supernatants were HIV-1 RNA positive, but negative for XMRV.

TABLE 1.

Detection of XMRV and HIV-1 in the plasma and PBMNC samples in Africa*

| Sample | Number tested | PCR positive (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | XMRV | ||

| Cameroon | |||

| Plasma | 105† | 54 (51) | 0 (0) |

| PBMNCs | 19 | 8 (42) | 0 (0) |

| PBMNC culture supernatants | 50 | 50 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Uganda | |||

| Plasma | 94‡ | 49 (52) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 268 | 161 (60) | 0 (0) |

Viral RNA isolated from plasma was analyzed for XMRV and HIV-1 using RT-nested PCR while genomic DNA extracted from PBMNCs was analyzed for XMRV and HIV-1 using nested PCR and (q)PCR. GAPDH was amplified in parallel as an internal control.

Anti-HIV–positive by rapid HIV-1 assay.

Among the Ugandan subjects, 38% were on antiretroviral therapy and had fully suppressed HIV viral levels (viral load <400 copies/mL).

Fig. 2.

PCR screening for XMRV and HIV-1. (A) RT-PCR products of 11 plasma samples (Lanes 1–11) collected in South Africa with XMRV gag gene primer pair (top panel) and HIV-1 gp41 primer pair (bottom panel). Lanes 12 and 13 = negative and positive controls of XMRV, respectively. (B) PCR products of 12 PBMNC samples (Lane 1–12) collected in Cameroon with XMRV gag (top panel), HIV-1 gp41 (middle panel), and hGAPDH gene (bottom panel). Lane 13 and 14 = negative and positive controls of XMRV, respectively.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the study reported here is the first attempt to evaluate the presence of XMRV in plasma or PBMNC samples collected from HIV-1-infected blood donors or individuals in African countries. We chose to use PCR methods for this study primarily because they had been shown to be more reliable and sensitive than other methods for detection in plasma and PBMNCs.3 Assay sensitivity was also evaluated in a collaborative study and determined by testing an analytical panel consisting of plasma spiked with cell culture supernatant containing XMRV. No substantial differences were observed compared with plasma assays from other participating laboratories in terms of sensitivity (unpublished data). The failure to detect XMRV in these African samples is unlikely due to assay methods including extraction and amplification of XMRV RNA and DNA because HIV-1 RNA and DNA were successfully amplified in parallel and GAPDH gene was positive in all of the PBMNC samples. Furthermore, our PCR assays have been shown to be at least as sensitive as those previously reported.1–3 Extra care has been taken to avoid possible contamination by including negative (water) controls in each round of PCR and using different work areas for nucleic acid extraction, PCR processing, and gel electrophoresis. It is possible that among the Ugandan subjects, ART may affect XMRV detection because XMRV has been shown to be susceptible to inhibition by AZT at relatively high concentration;16,17 however, only some patients in our study received AZT treatment and no evidence of XMRV was seen in any of the samples regardless of antiretroviral therapy suppression. It has been reported that activated PBMNCs can release XMRV particles.3 However, we were unable to detect XMRV RNA from the PBMNC culture supernatants, although they were positive for HIV-1 RNA. Another likely explanation for the negative results in our study is the likelihood of strain variation in African populations, which could affect detection by PCR-based methods. Finally, it is possible that some of the donors may have been infected with XMRV, but with transient viremia or without a significant infection in blood. Regardless, no evidence of XMRV infection was obtained in the African samples we studied using highly sensitive PCR methods. Further investigations on different populations and larger sample sizes are needed to fully determine the prevalence and distribution of XMRV in Africa and worldwide.

XMRV was first identified and has been confirmed in prostate cancer patients with a frequency of 10% to 27% in the United States.1,2,18 It has a high prevalence of 40% in prostate cancer patients carrying a homozygous R462Q mutation in the RNaseL gene.1 However, it was rarely detected in nonfamilial prostate cancer patients from Northern Europe (0.95%)6 and not detected at all in sporadic prostate cancer patients in Germany4 and Ireland.19 XMRV was also reported with high prevalence (67%) in CFS patients in the United States.3 However, another US study,20 two groups from the United Kingdom,5,8 and one Dutch group7 could not detect XMRV DNA or RNA in CFS patients. XMRV infection has been detected in non–prostate cancer or CFS individuals and healthy individuals including blood donors in the United States (3.75% by PCR),3 Germany (1.42%–3.2% by PCR),6,12 United Kingdom (0.76% by neutralization assay),8 and Japan (1.7% by serologic assay).9 These results indicate that approximately 1% to 4% of the general population may be infected with XMRV. However, our study and several other studies have been unable to demonstrate the presence of XMRV infection in the general population.4,7,8,20 There could be several possible reasons for these conflicting results. One possibility is a restricted geographic distribution of XMRV infection worldwide or focal outbreaks of XMRV infection in specific populations and areas. For example, XMRV is currently exclusively detected in the prostate cancer patients in the United States21 and CFS patients in one US study,3 but rarely in Europe except that a recent German study found XMRV infection in 2.3% to 9.9% of patients with respiratory tract infections.12 A second explanation could be the lower sensitivity and specificity of testing assays, in particular the serologic assays. There are currently no reference reagents for standardization of assays; therefore, it is difficult to make comparisons of results obtained in different laboratories using various methods. Hohn and colleagues4 were unable to detect XMRV-specific antibodies against XMRV env (gp70) and gag (pr65) proteins in prostate cancer patients and healthy control sera. Groom and coworkers8 reported a significant cross-reactivity between XMRV and other viruses including vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) in their neutralization assay. All of the serologic-positive samples are XMRV DNA and RNA negative.8 Third, the potential genetic variation of XMRV could result in “false-negative” detection.22 Although the current sequence data indicate that XMRV is highly conserved,3,10 it is possible that distinct strains of XMRV may exist.10,22 Finally, XMRV was identified within the past 5 years, and the epidemiologic data are limited pointing to the need for additional studies using well-standardized assays.

In summary, we screened 199 plasma samples, 19 PBMNC samples, and 50 cultured PBMNC supernatants of HIV-1-infected blood donors from Cameroon and HIV-1-positive individuals from Uganda for XMRV infection using sensitive PCR assays. None of the samples were found to be XMRV DNA or RNA positive. Therefore, our results failed to demonstrate the presence of XMRV in the African population we studied. However, it should be noted that the small sample size, and its heterogeneous nature, limits the statistical power of the study and the conclusions. Additional more extensive studies are needed to understand the epidemiology and geographic distribution of XMRV infection worldwide.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH.

We acknowledge Dr Robert H. Silverman for providing the XMRV infectious clone VP62 and Dr Kathryn S. Jones for the XMRV plasmid DNA. We thank Dr Eric Y. Wong and Hira Nakhasi for review of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CFS

chronic fatigue syndrome

- (q)PCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- XMRV

xenotropic murine leukemia virus–related virus

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

The findings and conclusions in this article have not been formally disseminated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and should not be construed to represent any Agency determination or policy.

References

- 1.Urisman A, Molinaro RJ, Fischer N, Plummer SJ, Casey G, Klein EA, Malathi K, Magi-Galluzzi C, Tubbs RR, Ganem D, Silverman RH, DeRisi JL. Identification of a novel Gammaretrovirus in prostate tumors of patients homozygous for R462Q RNASEL variant. Plos Pathog. 2006;2:e25. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Schlaberg R, Choe DJ, Brown KR, Thaker HM, Singh IR. XMRV is present in malignant prostatic epithelium and is associated with prostate cancer, especially high-grade tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16351–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906922106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3.Lombardi VC, Ruscetti FW, Das Gupta J, Pfost MA, Hagen KS, Peterson DL, Ruscetti SK, Bagni RK, Petrow-Sadowski C, Gold B, Dean M, Silverman RH, Mikovits JA. Detection of an infectious retrovirus, XMRV, in blood cells of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Science. 2009;326:585–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1179052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohn O, Krause H, Barbarotto P, Niederstadt L, Beimforde N, Denner J, Miller K, Kurth R, Bannert N. Lack of evidence for xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) in German prostate cancer patients. Retrovirology. 2009;6:92. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlwein O, Kaye S, McClure MO, Weber J, Wills G, Collier D, Wessely S, Cleare A. Failure to detect the novel retrovirus XMRV in chronic fatigue syndrome. Plos One. 2010;5:e8519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer N, Hellwinkel O, Schulz C, Chun FK, Huland H, Aepfelbacher M, Schlomm T. Prevalence of human gammaretrovirus XMRV in sporadic prostate cancer. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Kuppeveld FJ, Jong AS, Lanke KH, Verhaegh GW, Melchers WJ, Swanink CM, Bleijenberg G, Netea MG, Galama JM, van der Meer JW. Prevalence of xenotropic murine leukaemia virus-related virus in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome in the Netherlands: retrospective analysis of samples from an established cohort. BMJ. 2010;340:c1018. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groom HC, Boucherit VC, Makinson K, Randal E, Baptista S, Hagan S, Gow JW, Mattes FM, Breuer J, Kerr JR, Stoye JP, Bishop KN. Absence of xenotropic murine leukaemia virus-related virus in UK patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Retrovirology. 2010;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuta RA. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory. 2009. The prevalence of xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus in healthy blood donors in Japan Retroviruses. poster 100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffin JM, Stoye JP. Virology. A new virus for old diseases? Science. 2009;326:530–1. doi: 10.1126/science.1181349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong S, Klein EA, Das Gupta J, Hanke K, Weight CJ, Nguyen C, Gaughan C, Kim KA, Bannert N, Kirchhoff F, Munch J, Silverman RH. Fibrils of prostatic acid phosphatase fragments boost infections with XMRV (xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus), a human retrovirus associated with prostate cancer. J Virol. 2009;83:6995–7003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00268-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer N, Schulz C, Stieler K, Hohn O, Lange C, Drosten C, Aepfelbacher M. Xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related gammaretrovirus in respiratory tract. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1000–2. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.100066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spacek LA, Shihab HM, Kamya MR, Mwesigire D, Ronald A, Mayanja H, Moore RD, Bates M, Quinn TC. Response to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients attending a public, urban clinic in Kampala, Uganda. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:252–9. doi: 10.1086/499044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang C, Pieniazek D, Owen SM, Fridlund C, Nkengasong J, Mastro TD, Rayfield MA, Downing R, Biryawaho B, Tanuri A, Zekeng L, van der Groen G, Gao F, Lal RB. Detection of phylogenetically diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 groups M and O from plasma by using highly sensitive and specific generic primers. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2581–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2581-2586.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knouf EC, Metzger MJ, Mitchell PS, Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Tewari M, Miller AD. Multiple integrated copies and high-level production of the human retrovirus XMRV (xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus) from 22Rv1 prostate carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2009;83:7353–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00546-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakuma R, Sakuma T, Ohmine S, Silverman RH, Ikeda Y. Xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus is susceptible to AZT. Virology. 2010;397:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh IR, Gorzynski JE, Drobysheva D, Bassit L, Schinazi RF. Raltegravir is a potent inhibitor of XMRV, a virus implicated in prostate cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome. Plos One. 2010;5:e9948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold RS, Makarova NV, Osunkoya AO, Suppiah S, Scott TA, Johnson NA, Bhosle SM, Liotta D, Hunter E, Marshall FF, Ly H, Molinaro RJ, Blackwell JL, Petros JA. XMRV infection in patients with prostate cancer: novel serologic assay and correlation with PCR and FISH. Urology. 2010;75:755–61. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Arcy F, Foley R, Perry A, et al. No evidence of XMRV in Irish prostate cancer patients with the R462Q mutation. European Urology Supplements. 2008;7:271. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Switzer WM, Jia H, Hohn O, Zheng H, Tang S, Shankar A, Bannert N, Simmons G, Hendry RM, Falkenberg VR, Reeves WC, Heneine W. Absence of evidence of xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus infection in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy controls in the United States. Retrovirology. 2010;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman RH, Nguyen C, Weight CJ, Klein EA. The human retrovirus XMRV in prostate cancer and chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:392–402. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kean S. An indefatigable debate over chronic fatigue syndrome. Science. 2010;327:254–5. doi: 10.1126/science.327.5963.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]