Abstract

Objective

To examine how presentation of different stimuli impacts affect in nursing home residents with dementia.

Method

Participants were 193 residents aged 60 to 101 years from 7 Maryland nursing homes who had a diagnosis of dementia (derived from the medical chart or obtained from the attending physician). Cognitive functioning was assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and data pertaining to activities of daily living were obtained through the Minimum Data Set. Affect was assessed using observations of the 5 moods from Lawton’s Modified Behavior Stream. Baseline observations of affect were performed for comparisons. During the study, each participant was presented with 25 predetermined engagement stimuli in random order over a period of 3 weeks. Stimuli were categorized as live social, simulated social, manipulative, work/task-related, music, reading, or individualized to the participant’s self-identity. The dates of data collection were 2005–2007.

Results

Differences between stimulus categories were significant for pleasure (F6,144 = 25.137, P < .001) and interest (F6,144 = 18.792, P < .001) but not for negative affect. Pleasure and interest were highest for the live social category, followed by self-identity and simulated social stimuli for pleasure, and for manipulative stimuli in terms of the effect on interest. The lowest levels of pleasure and interest were observed for music. Participants with higher cognitive function had significantly higher pleasure (F1,97 = 6.27, P < .05). Although the general trend of the impact of the different categories was similar for different levels of cognitive function, there were significant differences in pleasure in response to specific stimuli (interaction effect: F6,92 = 2.31, P < .05). Overall, social stimuli have the highest impact on affect in persons with dementia.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study are important, as affect is a major indicator of quality of life and this study is the first to systematically examine the impact of specific types of stimuli on affect. As live social stimuli are not always readily available, particularly in busy nursing home environments, simulated social stimuli can serve as an effective substitute, and other stimuli should have a role in the activity tool kit in the nursing home. The relative ranking of stimuli was different for interest and pleasure. The findings demonstrate the differential effect of presentation of different types of stimuli on the affect of persons with dementia, and that, while the impact is greater on persons with higher levels of cognitive function, there is a different effect of varying stimuli even in persons with MMSE scores of 3 or lower. Future research should attempt to ascertain a person’s degree of interest in stimuli prior to developing an intervention.

Nursing home residents often find themselves in an understimulating environment, spending the majority of their time unengaged in any meaningful activity.1–3 When coupled with a lack of social contact, this state of inactivity results in boredom, loneliness, and behavioral problems,2 which can then translate to depression.4 Prolonged states of inactivity and understimulation can be particularly damaging to persons in nursing homes who suffer from dementia, serving to intensify the apathy, boredom, depressed mood, and loneliness that often accompany the progression of dementia.5,6 It has been demonstrated, however, that offering appropriate activities to older persons with dementia results in increased positive emotions, improvement in activities of daily living (ADL), improvement in quality of life,6–8 the development of constructive attitudes toward dementia among nursing staff members,9 and a decrease in manifestations of problem behaviors among nursing home populations.10

The positive impact of engagement with stimuli on the affect of nursing home residents has been reported.8,10–14 Moore and colleagues12 presented a variety of engagement activities to 3 nursing home residents and found that the residents’ levels of happiness increased with every activity presented, when comparing preactivity and postactivity affect. Some researchers have examined the impact of individualized interventions on affect. Kolanowski et al15 reported more positive affect after implementing activities that were tailored to meet individual needs. In a study of 167 nursing home residents with dementia, Cohen-Mansfield and colleagues10 created individualized interventions that matched each person’s physical and cognitive abilities as well as lifelong interests, hobbies, and past roles and found that these interventions significantly increased pleasure and interest and decreased agitation. These findings are supportive of Lawton and Nahemow,16 who have posited that adaptive behavior and positive affect are optimized when environmental press (ie, demands of the environment) approximates older adults’ levels of competence. Conversely, maladaptive behavior and negative affect result when the environmental press is so far beneath or exceeds an individual’s competence that boredom and atrophy of skills occur.

As previous research has found that stimuli in general are beneficial to persons with dementia, the next step is to identify the effectiveness of specific stimuli attributes. In the present article, we aim to illuminate the effect of stimuli on the affect of nursing home residents with dementia and focus on the following 3 hypotheses:

For Clinical Use.

-

♦

In this sample of 193 nursing home residents with dementia and a mean score of 7 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, presentation of any stimulus resulted in significantly more interest and pleasure than that observed during usual care.

-

♦

Pleasure and interest were highest for live human or pet companionship. Other engaging stimuli included, for pleasure, stimuli personalized to tap the self-identity of the person with dementia and simulated social stimuli (eg, robotic animals, respite videos) and, for interest, manipulative stimuli.

-

♦

As live social stimuli are not always readily available, particularly in the busy nursing home environment, simulated social stimuli can serve as an effective substitute, and other stimuli should be part of the activity tool kit.

Stimuli that are based on the person’s self-identity will result in more positive affect than other stimuli. This hypothesis is based on findings from a previous study17 of older adults with dementia that showed a significant increase in interest, pleasure, and involvement, as well as fewer agitated behaviors, with activities designed to correspond to each participant’s most salient identity as compared to nonindividualized activities.17

Social stimuli will have a more positive impact on affect than will other stimuli. The rationale for this hypothesis comes from our analyses18 of engagement to stimuli, which revealed that social stimuli are the most potent stimuli for engaging persons with dementia.

The impact of stimuli on affect will be greater for those persons with comparatively higher cognitive functioning. The rationale for this hypothesis is that individuals with comparatively higher cognitive functioning show more reactivity to the environment because apathy tends to increase as dementia progresses.19

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 193 residents of 7 Maryland nursing homes. All participants had a diagnosis of dementia (either derived from the medical chart or obtained from the attending physician). A total of 151 participants (78%) were female, and the mean age was 86 years, with a range from 60 to 101 years. The majority of participants (81%) were white, and most (65%) were widowed. Performance of ADL, which was obtained through the Minimum Data Set (MDS),20 had a mean rating of 3.6 (SD= 1.0; range, 1–5; scale ranged from 1 [independent] to 5 [complete dependence]). Cognitive functioning, as assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),21 had a mean rating of 7.2 (SD = 6.3; range, 0–23). Participants had a mean of 6.7 medical diagnoses. This project received Institutional Review Board approval.

Background Assessment

Data pertaining to background variables were retrieved from the residents’ charts at the nursing homes by a trained research assistant; these data included gender, age, marital status, medical information (medical conditions from which the resident suffers and a list of medications taken), and performance on ADL (from the MDS). Performance on ADL was assessed for 10 activities (bed mobility, transferring, locomotion on the unit, dressing, eating, toilet use, personal hygiene, bathing, bladder incontinence, and bowel incontinence) utilizing a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 representing maximum dependence; a mean ADL score was calculated for each participant. The MMSE was administered to each participant by a research assistant who was trained with regard to standardized administration and scoring procedures.

Assessment of Affect

As it is often impossible to elicit self-reported affect from persons with advanced dementia, affect was observationally assessed using the 5 moods from Lawton’s Modified Behavior Stream22: (1) pleasure—when the study participant smiles, laughs, or shows other outward manifestation of happiness; (2) interest—when the study participant is focused on someone or something, ie, eye tracking; visual scanning; facial, motoric, or verbal feedback; or eye contact; (3) depression—when the study participant appears upset or “down,” ie, cries, tears, or moans, or if the study participant verbally expresses depression, such as “I want to die”; (4) anxiety—when the study participant appears uptight, ie, motoric restlessness, furrowed brow, repeated motions, and facial expressions of fear or worry; and (5) anger—when the study participant exhibits explicit signs of anger, ie, clenched teeth, grimace, shouting, cursing, berating, punching, or physical aggression. In a previous study,23 we calculated an interrater agreement of 87.5% for the assessments of mood (n = 20).23 The 5 moods were measured on this 5-point scale: (1) never, (2) < 16 seconds, (3) less than half of the observation, (4) more than half of the observation, and (5) all or nearly all of the observation.

Data pertaining to affect were recorded through direct observations using specially designed software installed on a handheld computer, the PalmOne Zire 31 (Palm Inc, Sunnyvale, California).

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained for all study participants from their relatives or other responsible parties. Additional information on the informed consent process is available elsewhere.24 Our main criterion for inclusion was a diagnosis of dementia (either derived from the medical chart or obtained from the attending physician). The criteria for exclusion were (1) the resident had an accompanying diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, (2) the resident had no dexterity movement in either hand, (3) the resident could not be seated in a chair or wheelchair, and (4) the resident was younger than 60 years of age.

Once consent was obtained for eligible participants, background information was obtained from each participant’s chart in the nursing home. In addition, the MMSE was administered to each participant.

Baseline observations (when no stimulus was presented) of mood and behavior were performed daily for each study participant prior to the introduction of stimuli, once at the beginning of a morning engagement session and again at the beginning of an afternoon engagement session on another day. Each baseline observation lasted 3 minutes; these were used as comparison observations.

Each participant was presented with 25 predetermined engagement stimuli in random order over a period of 3 weeks (approximately 4 stimuli per day). Stimuli were categorized as live social, simulated social, manipulative, work/task-related, music, reading, or individualized to the study participant’s self-identity.

The category of live social stimuli included a real dog, a real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant. The category of simulated social stimuli included a life-like (“real”) baby doll, a childish-looking doll (ie, less real looking), a plush animal, a robotic animal (approximately $78 from stores such as Toys“R”Us), and a respite video.25,26 The category of manipulative stimuli included a squeeze ball, a tetherball, an expanding sphere, an activity pillow, building blocks, a fabric book, a wallet (for men) or purse (for women), and a puzzle. Work- or task-related stimuli included stamping envelopes, folding towels, flower arrangement, an envelope sorting task, and coloring with markers. The music category included only listening to music, and the reading category included only reading a large-print magazine. The final category of self-identity included 2 different stimuli that were matched to each participant’s past identity with respect to occupation, hobbies, or interests. Self-identity stimuli therefore varied across study participants, such that a ledger book could be given to a former accountant, while fabric samples could be presented to a former seamstress. In the majority of instances, the first self-identity stimulus tapped family identity and was either a videotape/DVD of a conversation with a family member of the study participant or family photographs.

With the exception of the self-identity stimuli, all stimuli were standardized across study participants. Treatment fidelity was checked through random unannounced checks and observations by the project coordinator or principal investigator.

Analytic Approach

For the analyses, we examined pleasure and interest as separate dependent variables and derived a new dependent measure, negative affect, which was the maximum value observed for sadness, anxiety, or anger. Data were examined using paired t tests and multivariate repeated measures of variance analysis via SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

To examine the first hypothesis, which asserts that stimuli that are based on the person’s self-identity will result in more positive affect than other stimuli, the levels of affect associated with the self-identity stimuli were compared to mean levels of affect associated with other stimuli in our study. For this analysis, the “other” stimuli category was made up of all stimuli presented to participants, excluding the self-identity stimuli and the live social stimuli. Our hypothesis was supported in that pleasure was significantly higher when residents were presented with the self-identity stimuli (mean = 1.50) as compared to the other stimuli (mean = 1.27) (t182 = 5.16, P < .001). Similarly, interest was significantly higher when residents were presented with the self-identity stimuli (mean = 3.55) as compared to the other stimuli (mean = 3.15) (t182 = 5.64, P <.001). There was no significant relationship for negative affect.

The second hypothesis asserts that social stimuli will have a more positive impact on affect than will other stimuli. To examine this hypothesis, we utilized the following 3 stimulus categories: live social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, and nonsocial stimuli (including music, reading, manipulative, and work- or task-related stimuli). We performed repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) in which the dependent variables were pleasure, interest, and negative affect. Differences between stimulus categories were significant for pleasure and interest but not for negative affect. In the case of pleasure, post hoc analyses (performed using Bonferroni pairwise comparisons; P <.001) revealed significant differences between all 3 stimulus categories; specifically, pleasure was highest for the live social category (mean= 1.916), followed by the simulated social category (mean =1.516) and the nonsocial category (mean = 1.192) (F2,189 = 85.353, P < .001). Additionally, Bonferroni pairwise comparisons revealed that interest was significantly higher in response to stimuli in the live social category (mean = 3.866) than to stimuli in either the simulated social category (mean = 3.232) or the nonsocial category (mean = 3.136) (F2,189 = 41.588, P < .001). There was no significant relationship for negative affect.

We further examined the impact of social stimuli (live as well as simulated) relative to the other categories of stimuli examined separately (self-identity stimuli, manipulative stimuli, music, reading, and work/task-related stimuli) via repeated-measures ANOVAs in which the dependent variables were pleasure, interest, and negative affect. Differences between stimulus categories were significant for pleasure and interest but not for negative affect (Table 1). In the case of pleasure, post hoc analyses (performed using Bonferroni pairwise comparisons; P < .001) revealed that pleasure was significantly higher for live social stimuli than for the other 6 stimulus categories; moreover, the pleasure elicited by simulated social and self-identity stimulus categories was significantly higher than that elicited by the other 4 stimulus categories, ie, they resulted in significantly more pleasure than music, manipulative, reading, and work/task stimuli (Table 1). As to interest, Bonferroni pairwise comparisons showed that live social stimuli and self-identity stimuli produced significantly more interest than the other stimulus categories (except for the difference between self-identity and reading, which was not significant). Music produced significantly less interest than all other stimulus categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Means for 7 Stimulus Categories and Results of Repeated-Measures Analyses of Variance Comparing Pleasure, Interest, and Negative Affect to These 7 Stimulus Categories

| Variable | Live Social |

Simulated Social |

Self- Identity |

Music | Manipulative | Reading | Work/ Task |

F(df = 6,144) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasure | 1.879 | 1.534 | 1.513 | 1.273 | 1.213 | 1.197 | 1.184 | 25.137*** |

| Interest | 3.827 | 3.235 | 3.587 | 2.657 | 3.150 | 3.317 | 3.221 | 18.792*** |

| Negative affect | 1.117 | 1.118 | 1.130 | 1.080 | 1.102 | 1.103 | 1.112 | 0.409 |

P <.001.

To clarify the variability within each category of stimuli, we examined the rank order of the stimuli in terms of pleasure, interest, and negative affect. As can be seen in Table 2, in many cases, specific stimuli within a category are indeed clustered together in terms of the ranking of their impact. There are, however, exceptions. For example, whereas the plush animal and respite video have a similar ranking in their impact on pleasure, these have very different rankings in terms of capturing the interest of the participant, in that the respite video had a high ranking and the plush animal had one of the lowest.

Table 2.

Means and Rankings of Pleasure, Interest, and Negative Affecta

| Stimulus | Category | Pleasure, Mean |

Pleasure Rank, 1 = Highest |

Interest, Mean |

Interest Rank, 1 = Highest |

Negative Affect, Mean |

Negative Affect Rank, 1 = Lowest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real baby | Live social | 3.03 | 1 | 4.58 | 1 | 1.05 | 1 |

| Real pet | Live social | 1.88 | 2 | 3.48 | 6 | 1.09 | 10 |

| 1-on-1 socializing with a research assistant | Live social | 1.84 | 3 | 4.15 | 2 | 1.14 | 20 |

| Life-like doll | Simulated social | 1.74 | 4 | 3.45 | 7 | 1.15 | 24 |

| Personalized, based on self-identity # 1 | Self-identity | 1.69 | 5 | 3.60 | 3 | 1.08 | 6 |

| Robotic animal | Simulated social | 1.56 | 6 | 3.29 | 11 | 1.09 | 9 |

| Childish doll | Simulated social | 1.48 | 7 | 3.21 | 15 | 1.13 | 18 |

| Respite video | Simulated social | 1.44 | 8 | 3.48 | 5 | 1.11 | 14 |

| Plush animal | Simulated social | 1.34 | 9 | 2.94 | 24 | 1.09 | 7 |

| Tetherball | Manipulative | 1.33 | 10 | 3.06 | 21 | 1.15 | 25 |

| Personalized, based on self-identity #2 | Self-identity | 1.31 | 11 | 3.51 | 4 | 1.16 | 26 |

| Flower arrangement | Work/task | 1.27 | 12 | 3.18 | 16 | 1.14 | 22 |

| Fabric book | Manipulative | 1.27 | 13 | 3.38 | 8 | 1.09 | 8 |

| Music | Music | 1.26 | 14 | 2.66 | 25 | 1.07 | 5 |

| Expanding sphere | Manipulative | 1.23 | 15 | 2.98 | 23 | 1.05 | 2 |

| Squeeze ball | Manipulative | 1.19 | 16 | 3.14 | 17 | 1.13 | 17 |

| Activity pillow | Manipulative | 1.19 | 17 | 3.02 | 22 | 1.10 | 13 |

| Wallet/purse | Manipulative | 1.19 | 18 | 3.23 | 13 | 1.13 | 19 |

| Folding towels | Work/task | 1.18 | 19 | 3.29 | 10 | 1.10 | 12 |

| Large-print magazine | Reading | 1.18 | 20 | 3.23 | 12 | 1.13 | 16 |

| Stamping envelopes | Work/task | 1.16 | 21 | 3.30 | 9 | 1.15 | 23 |

| Puzzle | Manipulative | 1.16 | 22 | 3.07 | 20 | 1.11 | 15 |

| Envelope sorting | Work/task | 1.14 | 23 | 3.22 | 14 | 1.07 | 4 |

| Coloring with markers | Work/task | 1.14 | 24 | 3.07 | 18 | 1.14 | 21 |

| Baseline | Baseline | 1.10 | 25 | 2.29 | 26 | 1.10 | 11 |

| Building blocks | Manipulative | 1.09 | 26 | 3.07 | 19 | 1.06 | 3 |

Table is organized by the ranking of pleasure.

The third hypothesis asserts that the impact of stimuli on affect will be greater for those persons with comparatively higher cognitive functioning. To perform these analyses, we divided our sample into comparatively higher-functioning study participants (highest third [34.6%] of our sample, with an MMSE score of ≥ 10 [mean = 14.6]) and comparatively lower-functioning study participants (lowest third [31.9%] of our sample, with an MMSE score of < 3 [mean = 0.5]). We then looked at whether or not affect was impacted differently by level of cognitive function at baseline, ie, when no stimulus was presented to the study participant, by performing t tests in which pleasure, interest, and negative affect at baseline were the dependent measures and MMSE (highest third vs lowest third) was the grouping factor. Results revealed that pleasure and interest were significantly higher at baseline for the comparatively higher-functioning study participants (mean =1.14 vs mean=1.06 [t105 = 2.14, P < .05] and mean = 2.47 vs mean = 2.01 [t123 = 3.04, P < .01], respectively).

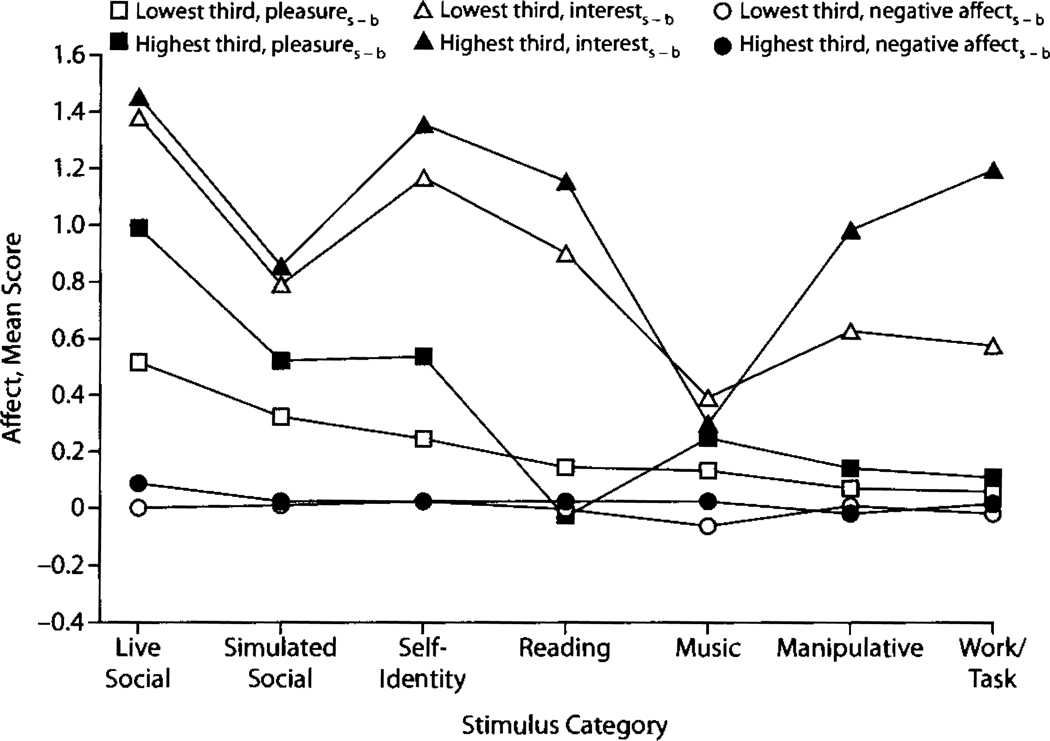

Because pleasure and interest at baseline were significantly greater for those residents with a higher level of cognitive function (ie, the highest third), we calculated new dependent variables to use for subsequent analyses. Specifically, we subtracted the level of affect during baseline from the level of affect during stimulus presentation trials, creating these variables: pleasures − b (ie, stimulus minus baseline), interests − b and negative affects − b. Repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed in which the within-subject factor was the 7 different stimulus categories and the between-subject factor was the level of cognitive functioning (lowest third vs highest third as determined by MMSE score). As can be seen in Table 3 and Figure 1, those with higher cognitive function had significantly higher pleasures − b than those with lower cognitive function (F1,97 = 6.27, P < .05). Moreover, both the main effect of stimulus category and the interaction of stimulus category with level of cognitive function were statistically significant (F6,92 = 16.19, P < .01; and F6,92 = 2.31, P < .05, respectively), reflected by study participants with higher cognitive functioning who had higher pleasures − b for 6 of the 7 stimulus categories, with the exception being reading. As to interests − b, the main effect of stimulus category was significant (F6,92 = 11.38, P < .01), with study participants, regardless of level of cognitive function, showing the highest and lowest mean levels of interests − b for live social stimuli and music stimuli, respectively (see Table 3). Although the interaction term for interest did not reach statistical significance (P= .07), the stimulus for which the gap in interest was greatest between those with low and high cognitive function was work/task (Figure 1). No other significant test statistics emerged from these analyses.

Table 3.

Means for 7 Stimulus Categories and Results of Repeated-Measures Analyses of Variance Comparing Pleasure, Interest, and Negative Affect to These 7 Stimulus Categories for Study Participants With Comparatively Higher Versus Lower Levels of Cognitive Functioninga,b

| Variable | MMSE | Live Social |

Simulated Social |

Self- Identity |

Reading | Music | Manipulative | Work/ Task |

Main Effect of the 7 Stimulus Categories, F(df= 6,92) |

Main Effect of Cognitive Function, F(df = 1,97) |

Interaction, F(df = 6,92) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasures − b | 16.19** | 6.27* | 2.31* | ||||||||

| Lowest third | 0.517 | 0.322 | 0.246 | 0.142 | 0.133 | 0.069 | 0.060 | ||||

| Highest third | 0.991 | 0.521 | 0.537 | −0.023 | 0.249 | 0.140 | 0.106 | ||||

| Interests − b | 11.38** | 2.49c | 2.03d | ||||||||

| Lowest third | 1.374 | 0.787 | 1.167 | 0.902 | 0.393 | 0.626 | 0.575 | ||||

| Highest third | 1.455 | 0.855 | 1.355 | 1.154 | 0.306 | 0.984 | 1.194 | ||||

| Negative affects − b | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.91 | ||||||||

| Lowest third | −0.002 | 0.016 | 0.029 | −0.009 | −0.065 | 0.008 | −0.022 | ||||

| Highest third | 0.086 | 0.015 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.021 | −0.018 | 0.014 | ||||

The level of affect during baseline was subtracted from the level of affect during stimulus presentation trials, creating these variables: pleasures − b, (ie, stimulus minus baseline), interests − b, and negative affects − b.

We divided our sample into comparatively higher-functioning participants (highest third [34.6%] of our sample, with an MMSE score of ≥ 10 [mean= 14.6]) and comparatively lower-functioning participants (lowest third [31.9%] of our sample, with an MMSE score of <3 [mean = 0.5]).

P =.118.

P =.070.

P <.05,

P < .01.

Abbreviation: MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Figure 1.

Affect (pleasure, interest, and negative affect) as a Function of the 7 Stimulus Categories for Study Participants With Comparatively Higher Levels (highest third) Versus Comparatively Lower Levels (lowest third) of Cognitive Functioning

Pleasure and interest generally showed a similar pattern of reaction to stimuli. For instance, self-identity stimuli had relatively high means for pleasure and interest, with both of these values being higher than those for other stimulus categories with the exception of the social stimulus categories (see Table 3). However, for some stimuli, the rankings diverged, as in the case of the work/task activities, which tended to have a higher ranking on interest than on pleasure (Figure 1 and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The hypothesis that stimuli based on self-identity would result in more positive affect was confirmed in that pleasure was indeed significantly higher in response to this category of stimuli. This result is congruent with previous findings by Cohen-Mansfield and colleagues,27 and Cohen-Mansfield et al.17 The hypothesis that social stimuli would have a more positive impact on affect as compared with other stimuli was also supported, consistent with previous findings.28 Confirmation of the first 2 hypotheses with prior research lends support to our methodology and findings. In terms of the third hypothesis, our results are not congruent with those of Lawton,29,30 whose environmental docility hypothesis states that “the less competent the individual, the greater the impact of environmental factors on that individual. ”29(p14) We found that those with comparatively higher cognitive function derived significantly more pleasure and interest from the environment (ie, the engagement stimuli) than did those with lower cognitive function. There was a significant interaction between the type of stimuli and level of cognitive functioning in the effect on pleasure. However, the ranking of stimuli associated with pleasure is similar for those with higher and lower levels of cognitive functioning. The main difference is that the impact is higher, or more easily evident, in those with higher levels of cognitive functioning.

Our results concerning music are of note, as we found that music produced low levels of interest and pleasure in comparison to other stimuli. To our knowledge, there are no other studies of music that utilize pleasure as a specific outcome measure in this population. Several studies have linked music to a decrease in agitation and/or apathy in persons with dementia31–33 and an increase in positive social behaviors.34 Gotell et al35 found that music increased awareness of and interest in their environment in persons with dementia. Our results agree with those findings in that music produced significantly higher levels of interest and pleasure than the baseline condition (P < .001 for both in paired-sample t tests; results are available from the authors). The finding that the impact of music was smaller than that of several other categories of stimulation maybe explained in several ways. First, social stimuli have a greater impact than music alone. Indeed, many music therapy interventions combine music and social stimuli. Second, although we inquired about participants’ preferences in music, most participants and caregivers did not provide such information, and, therefore, the music was not individualized. Research shows that individualized music can be more effective than music that is not specific to participant interests.36 Third, we utilized an observational tool, and it was sometimes difficult to assess interest and pleasure with certain stimuli, such as listening to music. In the case of an auditory stimulus, it can be difficult to determine whether or not a person is truly focusing on the stimulus. It is often easier to see the reaction to a stimulus such as a pet; in this case, the interest of the participant in the stimulus can be shown when the participant approaches or touches the pet, and the pleasure is more likely to be verbally expressed than with music. Consequently, the results should be compared to the impact of these stimuli on behavior such as agitation, which is more easily observable. Future research might also consider expanding the range of stimuli and settings, such as an adult daycare center or a person’s home.

The findings of the present study are important, as affect is a major indicator of quality of life. Consequently, it is beneficial to caregivers to understand which stimuli are most highly associated with pleasure and interest in persons with dementia. We found that both pleasure and interest levels were highest in responses to the live social category, which included the real dog, real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant. However, we recognize that it is often difficult or unrealistic to utilize live stimuli each time a nursing home resident is not engaged in any activity, and our results reveal additional effective, low-cost stimuli. The potent live social stimuli were followed, in their effect on pleasure, by simulated social stimuli, which included the lifelike baby doll, a childish-looking doll (ie, less real looking), a plush animal, a robotic animal, and a respite video. Stimuli based on the person’s present and past identity were similarly potent. This finding may be partially explained by the fact that many of those included simulated social stimuli such as a video of a family member talking to the resident. However, other stimuli, such as a tetherball and flower arrangement had similar levels of impact on pleasure. These stimuli are relatively easy to obtain and can be utilized at times when live social stimuli are unavailable. The relative ranking of stimuli was different for interest and pleasure. For example, even when stimuli groups were not associated with high rankings in the effect on levels of pleasure, eg, reading and task/work stimuli, they still produced relatively high levels of interest. Other stimuli that had a lower ranking in their effect on interest, like plush animals or dolls, can be useful for their greater relative impact on pleasure.

Future research should attempt to ascertain a person’s degree of interest in stimuli prior to developing an intervention. As the present study focused on the impact of stimulus type, interest level is not included in this article but is important for the efficacy of interventions.37 A limitation of the study is the substantial number of refusals received, and, for these individuals, affect was not assessed. However, these refusals underscore the important point that persons with dementia can and should exercise freedom of choice. Several researchers have written about the constraints and choices imposed on older persons in nursing homes,38,39 and professionals have a tendency to communicate with relatives rather than the patients themselves.38 In early and even moderate stages of dementia, persons can be capable of expressing meaningful opinions about their quality of care and quality of life40,41 and have preferences that can affect activity involvement.42

Although prior research had shown that the presentation of stimuli can influence affect,43,44 this study is the first to systematically examine the impact of specific types of stimuli on affect. The findings of the study are important in furthering the next step in research on stimulus engagement; that is, what specific stimuli or aspects of stimuli tend to be most effective in engaging persons with dementia. Our findings demonstrate the differential effect of presentation of different types of stimuli on the affect of persons with dementia, and, while the impact is greater on persons with higher levels of cognitive function, there is a differential effect of varying stimuli even in persons with MMSE scores of 3 or lower.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG R01 AG021497.

Footnotes

Disclosure of off-label usage: The authors have determined that, to the best of their knowledge, no investigation al information about pharmaceutical agents that is outside US Food and Drug Administration–approved labeling has been presented in this article.

Financial disclosure: Drs Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Thein, and Dakheel-Ali have no personal affiliations or financial relationships with any commercial interest to disclose relative to the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgio LD, Scilley K, Hardin JM, et al. Studying disruptive vocalization and contextual factors in the nursing home using computer-assisted real-time observation. J Gerontol. 1994;49(5):230–239. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.p230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Werner P. Observational data on time use and behavior problems in the nursing home. J Appl Gerontol. 1992;11(1):111–121. doi: 10.1177/073346489201100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ice GH. Daily life in a nursing home: has it changed in 25 years? J Aging Stud. 2002;16(4):345–359. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, et al. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buettner LL, Lundegren H, Lago D, et al. Therapeutic recreation as an intervention for persons with dementia and agitation: an efficacy study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1996;11(5):4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelman K, Altus D, Mathews R. Increasing engagement in daily activities by older adults with dementia. Appl Behav Anal. 1999;32(1):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buettner L, Martin S. Global Therapeutic Recreation III. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press; 1994. Never too old, too sick, or too bad for therapeutic recreation; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orsulic-Jeras S, Schneider NM, Camp CJ. Special feature: Montessori-based activities for long-term care residents with dementia. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2007;16(1):78–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sifton CB. Making dollars and sense: the cost-effectiveness of psychosocial therapeutic treatment. Alzheimers Care Q. 2001;2(4):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen-Mansfield J, Libin A, Marx MS. Nonpharmacological treatment of agitation: a controlled trial of systematic individualized intervention. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(8):908–916. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libin A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Therapeutic robocat for nursing home residents with dementia: preliminary inquiry. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(2):111–116. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore K, Delaney JA, Dixon MR. Using indices of happiness to examine the influence of environmental enhancements for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. J Appl Behav Anal. 2007;40(3):541–544. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams CL, Tappen RM. Effect of exercise on mood in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(5):389–397. doi: 10.1177/1533317507305588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeks S, Looney SW, Van Haitsma K, et al. BE-ACTIV: a staff-assisted behavioral intervention for depression in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):105–114. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolanowski AM, Litaker M, Buettner L. Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nurs Res. 2005;54(4):219–228. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawton MP, Nahemow LE. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H. Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;61(4):202–212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. The value of social attributes of stimuli for promoting engagement in persons with dementia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(8):586–592. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e9dc76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME. Prevalence of apathy, dysphoria, and depression in relation to dementia severity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(3):342–349. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris J, Hawes C, Murphy K, et al. Minimum Data Set. Natick, MA: Eliot Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Van Haitsma K, Klapper J. Observed affect in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1996;51(1):3–14. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. The effects of an enhanced environment on nursing home residents who pace. Gerontologist. 1998;38(2):199–208. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen-Mansfield J, Kerin P, Pawlson G, et al. Informed consent for research in a nursing home: processes and issues. Gerontologist. 1988;28(3):355–359. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall L, Hare J. Video respite for cognitively impaired persons in nursing homes. Am J Alzheimer Dis. 1997;12(3):117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lund DA, Hill RD, Caserta MS, et al. Video respite: an innovative resource for family, professional caregivers, and persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 1995;35(5):683–687. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen-Mansfield J, Golander H, Arnheim G. Self-identity in older persons suffering from dementia: preliminary results. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(3):381–394. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. Can persons with dementia be engaged with stimuli? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(4):351–362. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181c531fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawton MP. Environment and Aging. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawton MP. Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In: Lawton MP, Windley PG, Byerts TO, editors. Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches. New York, NY: Springer; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi AN, Lee MS, Cheong KJ, et al. Effects of group music intervention on behavioral and psychological symptoms in patients with dementia: a pilot-controlled trial. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119(4):471–481. doi: 10.1080/00207450802328136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark ME, Lipe AW, Bilbrey M. Use of music to decrease aggressive behaviors in people with dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(7):10–17. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raglio A, Bellelli G, Traficante D, et al. Efficacy of music therapy in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(2):158–162. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181630b6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziv N, Granot A, Hai S, et al. The effect of background stimulative music on behavior in Alzheimer's patients. J Music Ther. 2007;44(4):329–343. doi: 10.1093/jmt/44.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Götell E, Brown S, Ekman SL. Influence of caregiver singing and back-ground music on posture, movement, and sensory awareness in dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15(4):411–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerdner LA. Effects of individualized versus classical “relaxation” music on the frequency of agitation in elderly persons with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(1):49–65. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Regier NG, et al. The impact of personal characteristics on engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):755–763. doi: 10.1002/gps.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitwood T. The experience of dementia. Aging Ment Health. 1997;1(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tadd W, Bayer T, Dieppe P. Dignity in health care: reality or rhetoric. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2002;12(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L, et al. Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: the Dementia Quality of Life Instrument (DQoL) Gerontologist. 1999;39(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feinberg LF, Whitlatch CJ. Are persons with cognitive impairment able to state consistent choices? Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):374–382. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voelkl JE, Fries BE, Galecki AT. Predictors of nursing home residents’ participation in activity programs. Gerontologist. 1995;35(1):44–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarrott SE, Gozali T, Gigliotti CM. Montessori programming for persons with dementia in the group setting. Dementia. 2008;7(1):109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolanoswki AM, Buettner L, Costa PT, Jr, et al. Capturing interests: therapeutic recreation activities for persons with dementia. Ther Recreation J. 2001;35(4):220–235. [Google Scholar]