Abstract

Objectives

To determine which stimuli are 1) most engaging 2) most often refused by nursing home residents with dementia, and 3) most appropriate for persons who are more difficult to engage with stimuli.

Methods

Participants were 193 residents of seven Maryland nursing homes. All participants had a diagnosis of dementia. Stimulus engagement was assessed by the Observational Measure of Engagement.

Results

The most engaging stimuli were one-on-one socializing with a research assistant, a real baby, personalized stimuli based on the person’s self-identity, a lifelike doll, a respite video, and envelopes to stamp. Refusal of stimuli was higher among those with higher levels of cognitive function and related to the stimulus’ social appropriateness. Women showed more attention and had more positive attitudes for live social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, and artistic tasks than did men. Persons with comparatively higher levels of cognitive functioning were more likely to be engaged in manipulative and work tasks, whereas those with low levels of cognitive functioning spent relatively more time responding to social stimuli. The most effective stimuli did not differ for those most likely to be engaged and those least likely to be engaged.

Conclusion

Nursing homes should consider both having engagement stimuli readily available to residents with dementia, and implementing a socialization schedule so that residents receive one-on-one interaction. Understanding the relationship among type of stimulus, cognitive function, and acceptance, attention, and attitude toward the stimuli can enable caregivers to maximize the desired benefit for persons with dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, engagement, nursing home residents, stimuli

Nursing home residents spend a large majority of their day unoccupied. This has been linked to a decline in their physical, behavioral, and cognitive functioning, as well as their quality of life.1 More specifically, verbal and physical agitation have been directly correlated with understimulation in this population.2–4 In long-term care settings, problem behaviors were shown to increase when the person was inactive and to decrease when structured activities were offered.5

Methods have been devised for decreasing agitation using engagement with a wide range of stimuli. Exploring the efficacy of such nonpharmacological approaches to intervention is important because some drugs such as atypical antipsychotics have been associated with limited efficacy, negative side effects, and increased mortality in persons with dementia.6,7 Furthermore, according to the principles of dementia care delineated by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, nonpharmacological interventions should always be tried first.8 The selection of specific nonpharmacological therapies should be based on the unique characteristics of the patient, the caregiver, the availability of the therapy, the severity of the neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the likelihood that the specific symptoms will respond to the specific therapy.8

Buettner9,10 created a list of stimuli for engagement of persons with dementia termed “simple pleasures,” which could be used to reduce agitation and increase the amount of time spent in purposeful activity. These stimuli included 23 handmade objects that were appealing, safe, and therapeutic. Buettner identified those that were the most helpful with particular behaviors among residents with dementia. Other research showed various benefits of engagement of older persons with dementia. Using a crossover experimental design, one study found that engagement and positive affect were both significantly higher when the participants, 15 nursing home residents with dementia, were matched with stimuli corresponding to their skill and interest level.3 A number of studies have found that mental activity plays a protective role against cognitive decline,11,12 and further research is being performed to see whether there is a causal relationship between low activity levels and dementia development.13

In this article, we describe which stimuli (out of a possible 25) are most engaging to persons with dementia and how responses vary with respect to personal background (sex, education, and level of cognitive function). In addition, we examine the characteristics of persons who do not respond to any stimuli, the subgroups of stimuli that are most engaging to the persons who are least likely to respond, and how these differ from the stimuli that attract persons who are responsive.

METHODS

Participants

Research staff members approached the administrators of 10 Maryland nursing homes, regarding participation in the study and three refused. For the seven nursing homes that agreed to participate, research staff provided nursing home personnel with consent forms and nursing home staff members distributed the consent forms to guardians of residents with dementia. We received 211 consents of which 18 were excluded because of exclusion criteria (seven had bipolar disorder, one had schizophrenia, one was younger than 60 years, five had high Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] scores, and four could not use their hands) and 193 participated in the study. One hundred fifty-one participants were women (78%) and age averaged 86 years (range: 60–101). A majority of participants were white (81%) and most were widowed (65%). Activities of daily living performance, assessed through the Minimum Data Set,14 averaged 3.6 (standard deviation: 1.0; range: 1–5; where 1 = “independent,” 5 = “complete dependence”). Cognitive functioning averaged 7.2 (standard deviation: 6.3; range: 0–23) on the MMSE.15 Participants had an average of 6.7 medical diagnoses.

Assessments

Data pertaining to background variables were retrieved from the residents’ charts at the nursing homes and from the Minimum Data Set. The MMSE was administered by a trained research assistant. The Self-Identity Questionnaire16,17 was administered through a phone interview with the closest relative to determine enjoyable activities from the past and present. Engagement was assessed using the Observational Measurement of Engagement (OME).18 OME data were recorded through direct observations using a specially designed software installed on a handheld computer, the Palm One Zire 31. Specific OME outcome variables are attention to the stimulus during an engagement trial (four-point scale: not attentive to very attentive); attitude to the stimulus during an engagement trial (seven-point scale: very negative to very positive); duration referred to the amount of time that the participant was engaged with the stimulus (in seconds). This measure started after stimulus presentation and ended at 15 minutes or whenever the study participant was no longer engaged with the stimulus.

Finally, the amount of time that we observed stimulus manipulation by the study participant as well as talking to or about the stimulus during an engagement trial were recorded (four-point scale: none of the time to most/all the time). For the purpose of analysis, we recoded these into 0 and 1, where 0 = none and 1 = all other responses.

Interrater reliability of the OME was assessed by six dyads of research assistants’ ratings of the engagement measures during 48 engagement trials with nursing home residents. The interrater agreement rate for exact agreement was 75% for the five engagement measures. Intraclass correlation averaged 0.840 (range: 0.579–0.996) for the engagement outcome variables.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained for all the study participants from their relatives or other responsible parties, as described previously.19 Our criterion for inclusion was a diagnosis of dementia from the medical chart or attending physician. Criteria for exclusion were diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, no dexterity movement in either hand, inability to be seated in a chair or wheelchair, and age younger than 60 years.

As to the engagement protocol, each participant was presented with 25 predetermined engagement stimuli during a 3-week period (approximately four stimuli per day, presented throughout the day). Stimuli were categorized as: live social stimuli, which included a real dog, real baby, and one-on-one socializing with a research assistant; simulated social stimuli, which included a lifelike (real) baby doll, childish-looking doll, plush animal, robotic animal (~$78 from retail stores), and respite video20,21; a reading stimulus, which included a large-print magazine; manipulative stimuli, which included a squeeze ball, tetherball, expanding sphere, activity pillow, building blocks, fabric book, wallet (males)/purse (females), and puzzle; a music stimulus, which included listening to music; artistic task-related stimuli, which included flower arrangement and coloring with markers; work-related stimuli, which included stamping envelopes, folding towels, and an envelope sorting task; and two different self-identity stimuli that were matched to each participant’s past identity with respect to family, occupation, hobbies, or interests. These stimuli were determined on the basis of the Self-Identity Questionnaire administered to family members and residents. Self-identity stimuli varied across study participants, such that a book ledger could be given to a former accountant or fabric samples could be presented to a former seamstress. In the majority of instances, the first self-identity stimulus tapped family identity and was either family photographs or videotape/DVD of a conversation with a family member. With the exception of the self-identity stimuli (which were always individualized) and the music stimulus (which was, whenever possible, individualized), stimuli were standardized across study participants.

Five research staff members independently rated the social appropriateness of 23 stimuli (self-identity stimuli were not included) for the study participants using this scale: 1 = low appropriateness (i.e., considered appropriate for children rather than adults), 2 = moderately acceptable, 3 = highly acceptable. Ratings were based on perceptions of the extent to which each stimulus was an appropriate stimulus to present to an adult. A median was calculated for the ratings of each stimulus.

Stimuli were presented between 9:30 A.M.–12:30 P.M. and 2:00 P.M.–5:30 P.M. Individual engagement trials were separated by a washout period of at least 5 minutes. The order of stimulus presentation was randomized for each participant. Most often, two stimuli were presented in the morning and two in the evening. Each trial lasted a minimum of 3 minutes. If the participant showed no interest in the stimulus after 3 minutes, the trial was terminated. If the participant became engaged with the stimulus, the trial lasted throughout the extent of the participant’s engagement— up to a cutoff time of 15 minutes.

Statistical Analysis

To clarify which stimuli were most engaging, we rank ordered the different stimuli on the six indicators of engagement: stimulus acceptance, duration, attention, attitude, stimulus manipulation, and talking to or about the stimulus. Stimulus acceptance was derived as the percentage of trials for which a stimulus was not refused. Stimulus acceptance ranking of one indicates that the stimulus was refused least often. To understand the potential influence of social appropriateness on engagement, we correlated Spearman’s correlations between social appropriateness with the rankings of the four indicators of engagement.

To clarify the impact of type of stimulus, we compared the engagement value of stimuli from the eight categories (live social, simulated social, self-identity, reading, manipulative, music, artistic task, and work related) by repeated-measures analyses of variance in which the dependent measures were duration, attention, attitude, and stimulus acceptance. Post-hoc Bonferroni analyses were used to check which categories resulted in significantly longer durations of engagement than others.

To examine the effect of sex, cognitive function, and education on engagement, we examined the rank order of stimuli for men and women, for those with the highest and lowest thirds of cognitive function and those with high and low education on engagement duration and attitude. The higher level of cognitive function corresponded to MMSE levels of 10 or higher (34.6% of the sample) and the lowest corresponded to MMSE score of <3 (31.9% of the sample). The high level of education was an education beyond high school and the low level was high school or less. In addition, we conducted two types of statistical analysis. We correlated the ranking order of stimuli between men and women and between high and low levels of cognitive function for duration and for attitude using Spearman’s correlations. In addition, we performed two-way analyses of variance in which the dependent measures were duration, attention, attitude, and stimulus acceptance, the within-person factor was category of stimulus and the between-subject factor was sex or high and low level of cognitive functioning or high and low level of education.

To understand unresponsiveness, we identified the least responsive participants as those who responded (i.e., engagement time greater than 0) to the fewest stimuli to which they were presented and characterized them in terms of their age, cognitive function, and stimuli with which they were involved with. We then divided the sample into receptive (engaged during at least two-thirds of trials) and unresponsive (those who were engaged in a third or fewer trials) and examined stimulus rankings for these two groups. We correlated the stimuli rankings for the receptive and unresponsive study participants for engagement duration and attitude using Spearman’s correlations.

RESULTS

Which Stimuli are Most Engaging Overall, and Which are Accepted Most Often?

Rankings of the 25 engagement stimuli are presented in Table 1. The seven stimuli that were accepted most often were one-on-one socializing with a research assistant, a real baby, the first personalized self-identity stimulus (in 77% of the cases, this stimulus tapped family identity, e.g., family photos, audiotape, or video/DVD), envelopes to stamp, a fabric book, the second personalized self-identity stimulus, and music. With the exception of the fabric book, the aforementioned stimuli had received the highest rating of social appropriateness. Stimuli that were refused most often included the plush animal, coloring with markers, robotic animal, childish-looking doll, and activity pillow, and all had received the lowest appropriateness rating.

TABLE 1.

Overall Responsiveness to 25 Stimuli: Ranking of Different Aspects of Engagementa Ordered by Engagement Duration

| Type of Stimulus |

Social Appropriatenessb |

Stimulus Acceptancec |

Engagement Durationd |

Attentiond | Attituded | Stimulus Manipulatione |

Talking to or About Stimuluse |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-on-one socializing with a research assistant | Live social | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | 1 |

| Real baby | Live social | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 3 |

| Personalized—based on self-identity 1 | Identity | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | NA | 6 | |

| Personalized—based on self-identity 2 | Identity | 6 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 18 | 9 | |

| Respite video | Simulated social | 3 | 18 | 5 | 17 | 8 | NA | 8 |

| Lifelike doll | Simulated social | 2 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Envelope sorting | Work | 2 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 17 | 9 | 18 |

| Folding towels | Work | 3 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 16 | 6 | 16 |

| Stamping envelopes | Work | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 23 | 4 | 11 |

| Large-print magazine | Reading | 3 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 22 |

| Coloring with markers | Task | 1 | 24 | 11 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 20 |

| Flower arrangement | Task | 3 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 13 |

| Building blocks | Manipulative | 1 | 14 | 13 | 21 | 24 | 14 | 24 |

| Fabric book | Manipulative | 1 | 5 | 14 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 12 |

| Robotic animal | Simulated social | 1 | 23 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| Real pet | Live social | 3 | 9 | 16 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 2 |

| Childish doll | Simulated social | 1 | 22 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 7 |

| Wallet/purse | Manipulative | 3 | 11 | 18 | 14 | 18 | 8 | 19 |

| Puzzle | Manipulative | 2 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 21 | 11 | 17 |

| Squeeze ball | Manipulative | 1 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 2 | 15 |

| Music | Music | 3 | 7 | 21 | 25 | 25 | NA | 25 |

| Plush animal | Simulated social | 1 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 11 | 16 | 10 |

| Expanding sphere | Manipulative | 1 | 17 | 23 | 23 | 20 | 19 | 21 |

| Tetherball | Manipulative | 2 | 20 | 24 | 19 | 22 | 15 | 23 |

| Activity pillow | Manipulative | 1 | 21 | 25 | 24 | 15 | 10 | 14 |

Notes:

The seven highest rankings are bolded for stimulus acceptance, engagement duration, attention, attitude, stimulus manipulation, and talking to or about the stimulus.

Social appropriateness: five staff members independently rated the social appropriateness of the stimuli as 1 = low appropriateness, 2 = moderately appropriate, or 3 = highly appropriate, and a median of the ratings was calculated for each stimulus.

Percentage of stimulus acceptance out of the total trials.

Based on means.

Based on frequency 0 = No, 1 = Yes.

NA, not available.

The engagement stimuli with the highest rankings for duration, attention, and/or attitude included one-on-one socializing, a real baby, and both personalized self-identity stimuli (Table 1). Duration was high for a respite video, and attitude was relatively high for a real pet, lifelike doll, and robotic animal. Interestingly, the respite video, lifelike doll, and robotic animal received comparatively low rankings with regard to stimulus acceptance (i.e., these were refused relatively often). As to stimulus manipulation, the seven stimuli with the highest rankings were a fabric book, squeeze ball, robotic animal, envelopes to stamp, large-print magazine, towels to fold, and lifelike doll. Finally, the seven stimuli that evoked the most talking by the study participants were one-on-one socializing, a real pet, real baby, lifelike doll, robotic animal, the first personalized self-identity stimulus, and childish-looking doll.

Taken together, some interesting findings emerged for individual stimuli. In the case of the lifelike looking doll, we found that rankings for engagement duration, attention, and attitude were all high, but this stimulus was refused often (i.e., had a relatively low stimulus acceptance ranking). Similarly, the respite video had a relatively low stimulus acceptance ranking, even though it had high rankings of engagement duration and positive attitude. An examination of Table 1 reveals that refusal tended to be highest (i.e., high stimulus acceptance rankings) with stimuli that had low social appropriateness, such as those that are considered appropriate for children (27.2% for the childish doll, 28.6% for the plush animal, and 28% for the coloring with markers). The correlation between appropriateness and ranking of rate of acceptance was r = −0.682, p <0.001, N = 23 (the two self-identity stimuli were excluded); the correlation with ranking of duration was −0.491, p = 0.017, and with attention −0.467, p = 0.025 (all p values two-tailed). Correlations with ranking of attitude, talking to or about stimulus, and stimulus manipulation were not statistically significant.

The comparisons of the eight categories of stimuli by repeated-measures analyses of variance are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in the first four rows of the Table 2, the main effect of stimulus category was statistically significant for the four engagement-dependent measures, with the live social and self-identity stimuli emerging as most engaging, followed by work for engagement duration and simulated social for attitude, and then by reading and artistic task for both. Post-hoc Bonferroni analyses (available from authors) showed that, for engagement duration, engagement with live social stimuli was significantly longer than with all other stimuli; engagement duration with stimuli based on self-identity was significantly longer than all remaining stimuli with the exception of work stimuli; work, reading, artistic task, and simulated social stimuli were all significantly more engaging (in terms of duration) than music and manipulative stimuli but were not significantly different from each other.

TABLE 2.

Means and F Scores for Engagement Duration, Attention, Attitude, and Stimulus Acceptance as a Function of Stimuli Category, Sex, and Cognitive Function

| Live Social |

Self- Identity |

Work | Reading | Artistic Task |

Simulated Social |

Manipulative | Music |

F Statistic (Main Effect of Group) |

F Statistic (Main Effect Stimulus Category) |

F Statistic (Interaction Term) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||||||||||

| Duration | 389 | 234 | 183 | 164 | 161 | 159 | 109 | 100 | F[7,181] = 66.98a | ||

| Attention | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | F[7,139] = 40.83a | ||

| Attitude | 5.4 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.6 | F[7,138] = 34.71a | ||

| Acceptance | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.81 | F[7,181] = 11.28a | ||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Duration | |||||||||||

| Female | 393 | 232 | 189 | 161 | 178 | 173 | 114 | 108 | F[1,186] = 2.29 | F[7,180] = 44.80a | F[7,180] = 1.57 |

| Male | 372 | 241 | 162 | 175 | 100 | 107 | 90 | 73 | |||

| Attention | |||||||||||

| Female | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.7 | F[1,144] = 2.40 | F[7,138] = 26.02a | F[7,138] = 2.30b |

| Male | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.7 | |||

| Attitude | |||||||||||

| Female | 5.4 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | F[1,143] = 1.47 | F[7,137] = 21.43a | F[7,137] = 2.16b |

| Male | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.6 | |||

| Acceptance | |||||||||||

| Female | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.81 | F[1,186] = 0.01 | F[7,180] = 11.05a | F[7,180] = 1.66 |

| Male | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.82 | |||

| Cognitive functionc | |||||||||||

| Duration | |||||||||||

| Low | 316 | 197 | 91 | 127 | 104 | 145 | 84 | 65 | F[1,119] = 14.87a | F[7,113] = 36.21a | F[7,113] = 6.89a |

| High | 423 | 237 | 247 | 205 | 195 | 153 | 121 | 176 | |||

| Attention | |||||||||||

| Low | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | F[1,92] = 52.12a | F[7,86] = 23.93a | F[7,86] = 6.12a |

| High | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 | |||

| Attitude | |||||||||||

| Low | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.5 | F[1,92] = 29.46a | F[7,86] = 19.35a | F[7,86] =1.95 |

| High | 5.7 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.8 | |||

| Acceptance | |||||||||||

| Low | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.91 | F[1,120] = 38.13a | F[7,114] = 9.63a | F[7,114] =4.93a |

| High | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.72 |

p <0.001.

p <0.05.

Cognitive function levels include the highest and lowest thirds of the sample.

Does Responsiveness to Stimuli Vary With Respect to Gender, Education, and Level of Cognitive Function?

The Impact of Gender

As can be seen in Table 3, there was a general concordance in the ranking of stimuli between men and women. The correlations between the rankings were positive and significant for duration (r = 0.827, N = 25, p <0.001) and for attitude (r = 0.672, N = 25, p <0.001). There were, however, differences between men and women, as can be seen in Table 3 (e.g., an average duration spent engaged with a baby was longer for women by about 120 seconds, and although the simulated baby i.e., the lifelike doll was ranked five for attitude by both genders, women were, on an average, engaged for 90 more seconds). Social stimuli, e.g., a respite video and childish doll, were shown a similar preference by women, whereas men were more likely to be involved with the large-print magazine and in the work activity of stamping envelopes.

TABLE 3.

Ranking of Engagement Duration and Attitude by Sex and Cognitive Function

| Ranking Females | Ranking Males | Ranking: High Cognitive Functioninga (MMSE Score of 10 or Higher) |

Ranking: Low Cognitive Functioninga (MMSE Score <3) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus | Duration | Attitude | Duration | Attitude | Duration | Attitude | Duration | Attitude |

| One-on-one socializing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Real baby | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Self-identity 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Lifelike doll | 4 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Respite video | 5 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 6 |

| Self identity 2 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| Envelope sorting | 7 | 18 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 14 | 14 | 17 |

| Folding towels | 8 | 13 | 9 | 22 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 21 |

| Coloring with markers | 9 | 17 | 19 | 25 | 11 | 19 | 15 | 20 |

| Flower arrangement | 10 | 12 | 16 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| Stamping envelopes | 11 | 23 | 6 | 15 | 7 | 22 | 13 | 18 |

| Building blocks | 12 | 24 | 13 | 23 | 9 | 24 | 20 | 24 |

| Large-print magazine | 13 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 13 |

| Robotic animal | 14 | 7 | 17 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 11 | 10 |

| Fabric book | 15 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 17 | 12 | 7 | 8 |

| Childish doll | 16 | 6 | 23 | 20 | 21 | 7 | 9 | 7 |

| Real pet | 17 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 22 | 4 |

| Wallet/purse | 18 | 20 | 14 | 13 | 20 | 21 | 12 | 23 |

| Puzzle | 19 | 21 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 22 |

| Squeeze ball | 20 | 16 | 18 | 10 | 19 | 13 | 23 | 11 |

| Music | 21 | 25 | 21 | 24 | 15 | 25 | 24 | 25 |

| Plush animal | 22 | 9 | 22 | 21 | 22 | 10 | 17 | 14 |

| Tetherball | 23 | 22 | 24 | 14 | 25 | 23 | 18 | 15 |

| Activity pillow | 24 | 14 | 25 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 16 | 12 |

| Expanding sphere | 25 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 23 | 20 | 25 | 16 |

We divided the cognitive function of the population into thirds.

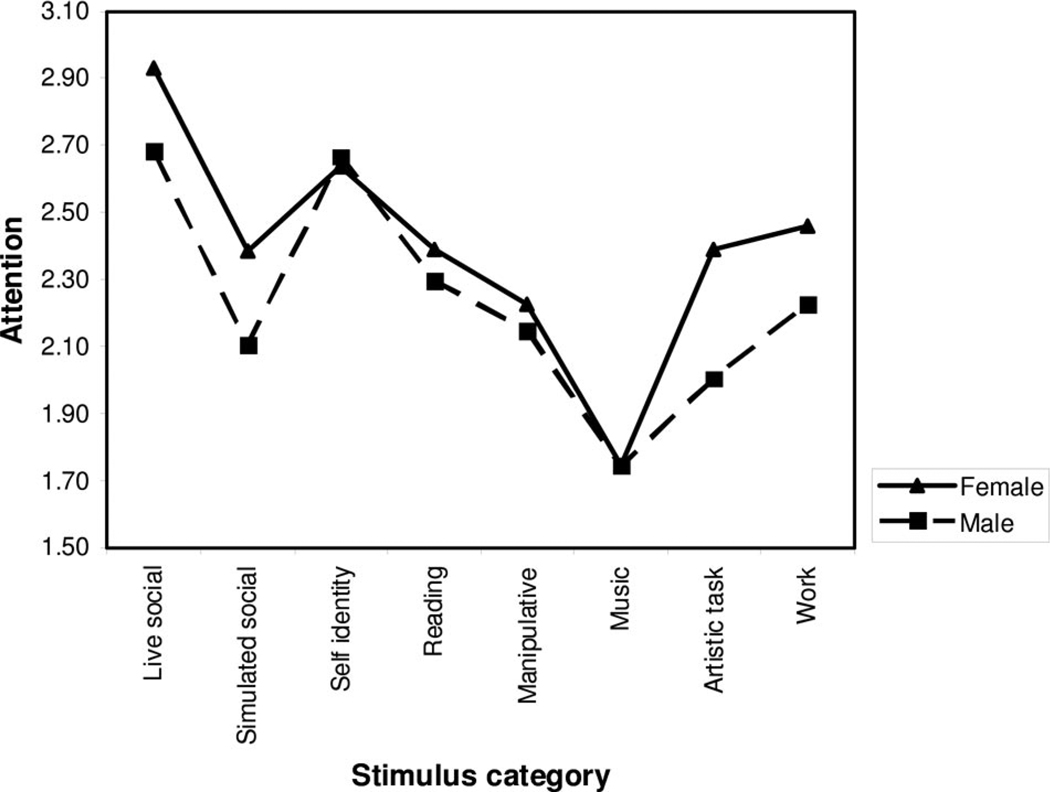

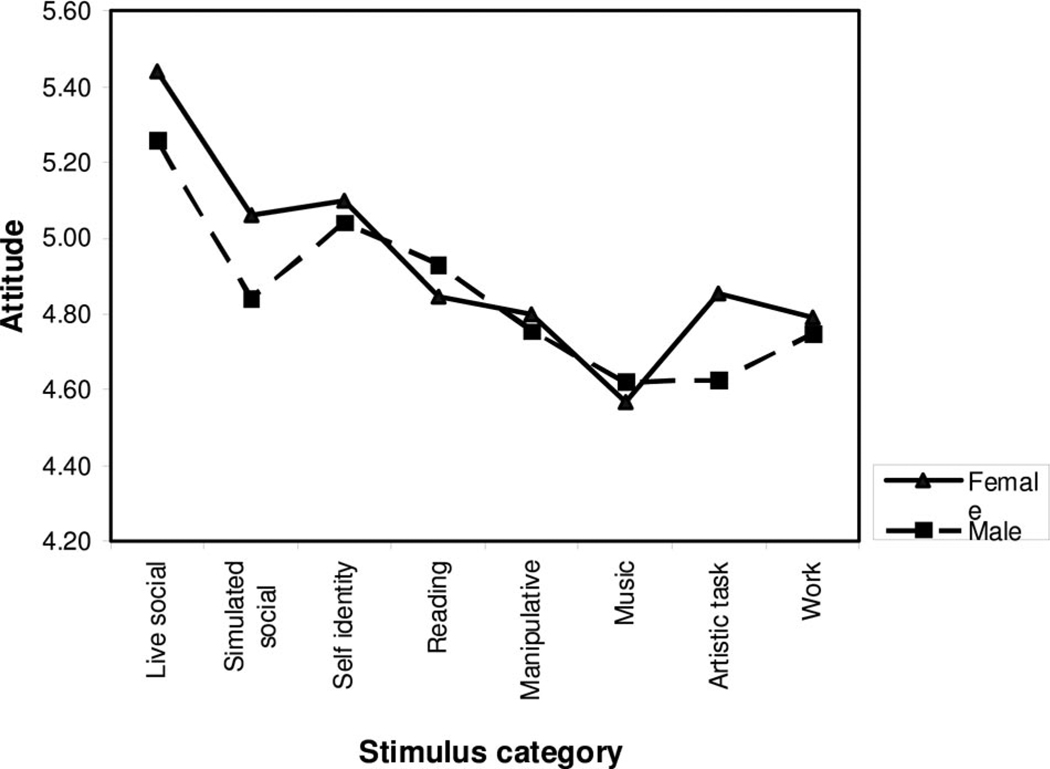

The two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance with stimulus category and sex as the within and between factors, respectively are presented in Table 2. The main effect of stimulus category was statistically significant for the four engagement-dependent measures as were the interaction terms for analyses pertaining to attention and attitude (F[7,138] = 2.304, p <0.05; F[7,137] = 2.163, p <0.05, respectively). Male and female study participants had comparable responses to some of the stimulus categories, but females showed more attention and had more positive attitudes for live social stimuli, simulated social stimuli, and artistic tasks than did men. In addition, with respect to work-related stimuli, women were observed to show more attention than did men (Figs. 1 and 2). The main effect of sex did not reach statistical significance for any of the four dependent measures.

FIGURE 1.

Mean Attention to the Eight Stimulus Categories as a Function of Gender

FIGURE 2.

Mean Attitude to the Eight Stimulus Categories as a Function of Gender

The Impact of Cognitive Function

Live social and self-identity stimuli were among the most highly ranked items regardless of cognitive level. Persons with comparatively higher levels of cognitive functioning were also more likely to spend the longest amounts of time being engaged in active, work-related tasks, such as sorting envelopes, stamping envelopes, and folding towels; however, simulated social stimuli, which permit less active responses, resulted in some of their most positive attitude scores (Table 3). In contrast, simulated social stimuli, such as the lifelike doll and the respite video, were among the most highly ranked items for both duration and attitude among those with low levels of cognitive functioning. The correlations between the rankings of those with comparatively higher and those with low levels of cognitive functioning were significant and positive for duration (r = 0.494, N = 25, p <0.05) and attitude (r = 0.793, N = 25, p <0.001).

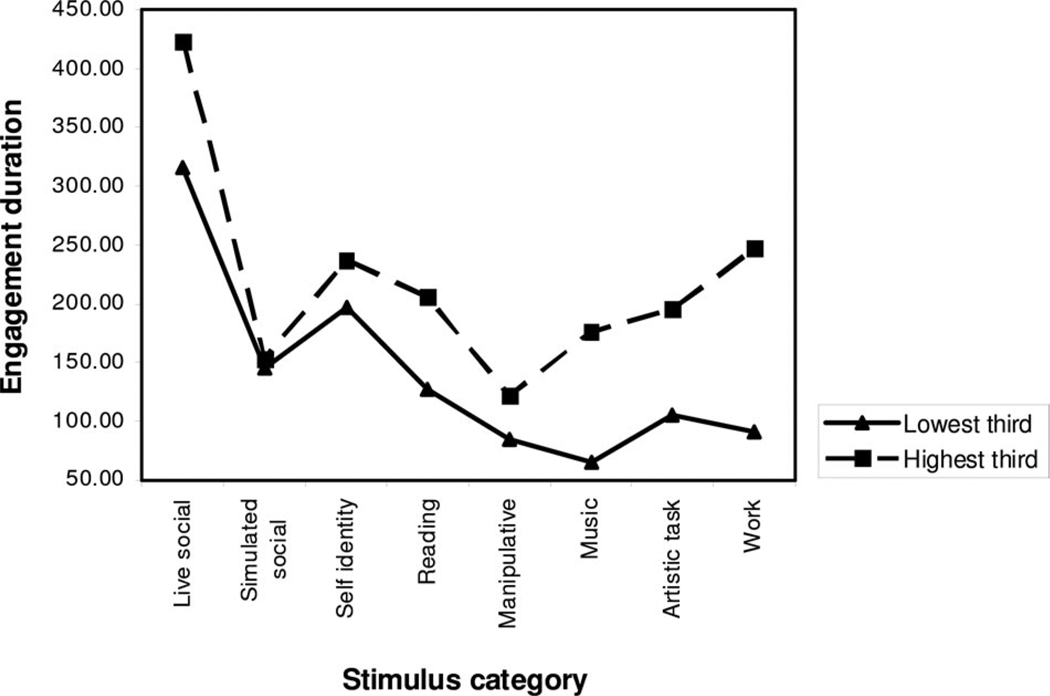

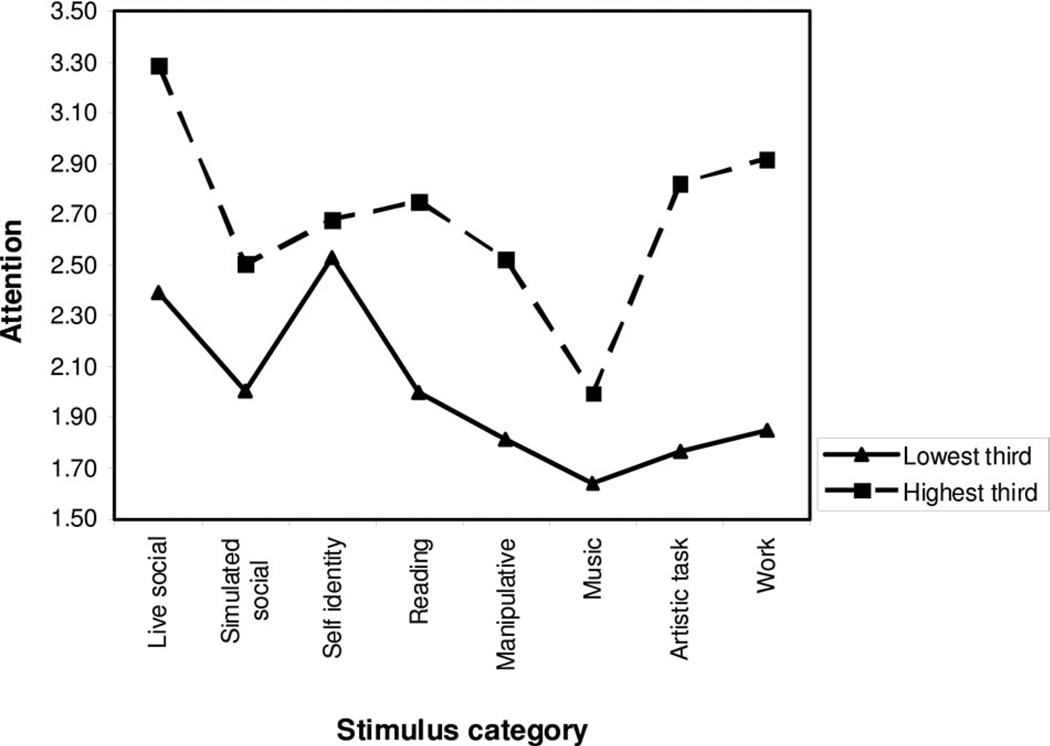

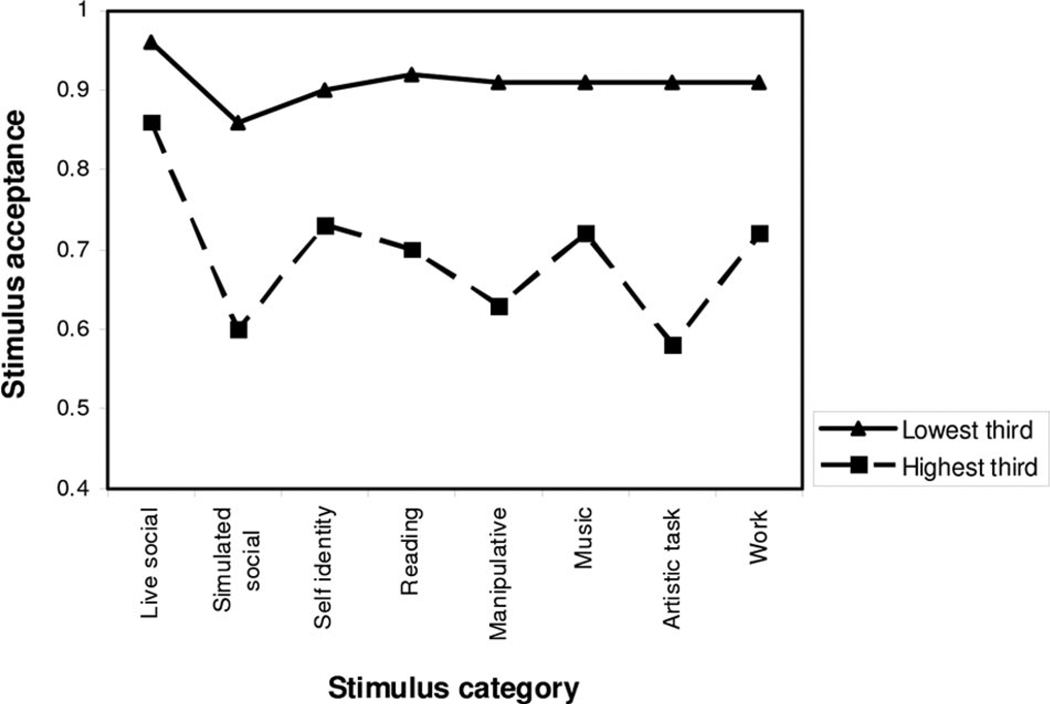

In the two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance, with cognitive functioning as the between-subjects variable, the main effects for both group and stimulus category for duration, attention, attitude, and acceptance were significant (Table 2). The significant interaction term for duration (Table 2) is reflected in Fig. 3, where study participants with comparatively higher cognitive functioning were engaged longer for seven of the stimulus categories, the exception being the category of simulated social stimuli where mean engagement duration did not appear to be influenced by level of cognitive functioning. The interaction term for attention was also significant (Table 2). Overall, participants with comparatively higher cognitive functioning had higher levels of attention for all eight categories of stimuli, most noticeably for live social stimuli, artistic tasks, work-related stimuli, and reading; the smallest difference between residents with higher and lower levels of cognitive functioning was seen with attention to self-identity stimuli (Fig. 4). Finally, the interaction term for stimulus acceptance was statistically significant (Table 2). As can be seen in Fig. 5, study participants with low cognitive functioning had consistently higher stimulus acceptance; in contrast, those with comparatively higher cognitive functioning had lower stimulus acceptance, refusing stimuli more often (roughly 30% of the time). However, mean scores for both groups were closest for live social stimuli, indicating that this is the most acceptable stimulus regardless of level of cognitive impairment. Analyses pertaining to education suggested that education did not affect engagement (these results are available from the authors).

FIGURE 3.

Mean Engagement Duration Toward the Eight Stimulus Categories for the Lowest Versus Highest Levels of Cognitive Function

FIGURE 4.

Mean Attention Toward the Eight Stimulus Categories for the Lowest Versus Highest Levels of Cognitive Function

FIGURE 5.

Mean Stimulus Acceptance Across the Eight Stimulus Categories for the Lowest Versus Highest Levels of Cognitive Function

Are Those Who are Least Likely to Respond to Any Stimuli More Likely to Respond to Different Stimuli Than the Stimuli That Attract Persons Who are Responsive?

There were three participants who were engaged in fewer than five trials (two engaged in only four trials and one engaged in only two trials). All three were women, white, widowed, and had finished high school. They were 89, 95, and 96 years, with MMSE scores of 0, 6, and 10. The only activity in which all three were engaged was one-on-one socializing. Two of the three were engaged in the individualized self-identity activities. The other activities that resulted in their engagement were the puzzle, stamping envelopes, folding towels, and building blocks.

Stimulus ranking for receptive (engaged during at least two-thirds of trials) and unresponsive (those who were engaged in a third or fewer trials) participants are presented in Table 4. For the receptive study participants, social stimuli, both live and simulated, and the task-oriented activities were engaging for the longest amount of time. The unresponsive participants appeared to be more selective in that higher levels of engagement were reserved for those stimuli that were real (real baby or real pet) as opposed to the simulated social stimuli. They also showed relatively high responsiveness to music and to the large-print magazine, both real-world activities in which they would have engaged in the past in contrast to the other stimuli that were more contrived. Both groups showed comparatively high levels of engagement with the self-identity stimuli. There was a high correlation between the rankings for the receptive and unresponsive study participants for engagement duration (r = 0.678, N=25, p <0.001) and for attitude (r = 0.747, N = 25, p <0.001).

TABLE 4.

Stimuli Most Engaging to Persons Who are Receptive (Engaged in Two-Thirds of the Trials or More) and to Persons Who are Relatively Unresponsive (Engaged in a Third or Fewer of the Trials)

| Receptive, n = 82 | Unresponsive, n = 35 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus | Percentage of Residents Responded to the Stimulus |

Engagement Duration |

Attitude | Percentage of Residents Responded to the Stimulus |

Engagement Duration |

Attitude | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Rank | Mean | SD | Rank | Mean | SD | Rank | Mean | SD | Rank | |||

| One-on-one socializing | 98.8 | 758.44 | 259.01 | 1 | 5.75 | 0.63 | 2 | 85.7 | 447.57 | 360.76 | 1 | 5.09 | 0.57 | 2 |

| Self-identity 1 | 95.0 | 350.76 | 262.53 | 2 | 5.44 | 0.60 | 4 | 64.7 | 108.31 | 156.45 | 3 | 4.83 | 0.66 | 3 |

| Lifelike doll | 96.3 | 343.15 | 258.74 | 3 | 5.47 | 0.70 | 3 | 28.6 | 30.9 | 80.76 | 9 | 4.52 | 0.70 | 7 |

| Respite video | 96.3 | 342.41 | 292.09 | 4 | 5.21 | 0.50 | 8 | 37.1 | 29.57 | 65.14 | 10 | 4.53 | 0.60 | 6 |

| Self identity 2 | 97.5 | 328.64 | 273.45 | 5 | 5.08 | 0.50 | 13 | 31.4 | 51.7 | 139.23 | 6 | 4.55 | 0.74 | 5 |

| Real baby | 90.5 | 323.24 | 318.43 | 6 | 6.1 | 0.70 | 1 | 75.0 | 113.25 | 129.97 | 2 | 5.83 | 0.76 | 1 |

| Envelope sorting | 95.1 | 311.22 | 264.86 | 7 | 5.06 | 0.43 | 15 | 20.0 | 28.14 | 87.06 | 11 | 4.16 | 0.44 | 24 |

| Folding towels | 95.1 | 296.38 | 265.70 | 8 | 5.04 | 0.44 | 17 | 31.4 | 26.79 | 70.16 | 12 | 4.4 | 0.51 | 13 |

| Flower arrangement | 95.1 | 284.52 | 254.71 | 9 | 5.14 | 0.49 | 11 | 20.0 | 31.79 | 102.60 | 8 | 4.37 | 0.71 | 15 |

| Coloring with markers | 85.4 | 281.20 | 259.11 | 10 | 4.98 | 0.50 | 22 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 13.66 | 25 | 4.12 | 0.27 | 25 |

| Large-print magazine | 97.6 | 269.73 | 258.23 | 11 | 5.03 | 0.46 | 19 | 31.4 | 61.63 | 136.00 | 5 | 4.39 | 0.55 | 14 |

| Stamping envelopes | 98.8 | 268.48 | 248.03 | 12 | 4.95 | 0.53 | 23 | 22.9 | 25.4 | 78.38 | 13 | 4.17 | 0.68 | 22 |

| Robotic animal | 96.3 | 265.57 | 237.85 | 13 | 5.32 | 0.62 | 6 | 34.3 | 17.79 | 40.49 | 18 | 4.46 | 0.62 | 9 |

| Building blocks | 93.9 | 257.30 | 261.72 | 14 | 4.88 | 0.44 | 24 | 11.4 | 23.96 | 102.44 | 16 | 4.17 | 0.37 | 23 |

| Fabric book | 96.3 | 239.33 | 191.88 | 15 | 5.16 | 0.44 | 10 | 37.1 | 24.37 | 42.15 | 15 | 4.42 | 0.51 | 11 |

| Childish doll | 96.3 | 205.86 | 209.78 | 16 | 5.27 | 0.68 | 7 | 31.4 | 19.34 | 36.28 | 17 | 4.45 | 0.47 | 10 |

| Real pet | 81.0 | 181.14 | 253.83 | 17 | 5.42 | 0.92 | 5 | 27.3 | 62.76 | 185.71 | 4 | 4.78 | 0.97 | 4 |

| Wallet/purse | 91.5 | 173.04 | 177.28 | 18 | 4.98 | 0.51 | 21 | 31.4 | 24.76 | 56.67 | 14 | 4.4 | 0.47 | 12 |

| Puzzle | 92.7 | 172.83 | 158.10 | 19 | 5 | 0.44 | 20 | 22.9 | 12.47 | 48.03 | 20 | 4.3 | 0.45 | 19 |

| Squeeze ball | 95.1 | 165.15 | 187.81 | 20 | 5.04 | 0.38 | 16 | 45.7 | 16.39 | 30.79 | 19 | 4.5 | 0.42 | 8 |

| Stuffed animal | 91.5 | 152.97 | 171.24 | 21 | 5.21 | 0.59 | 9 | 22.9 | 10.71 | 25.92 | 21 | 4.33 | 0.47 | 17 |

| Music | 75.6 | 144.52 | 201.95 | 22 | 4.71 | 0.55 | 25 | 37.1 | 44.66 | 96.35 | 7 | 4.35 | 0.45 | 16 |

| Activity pillow | 93.9 | 139.73 | 154.11 | 23 | 5.06 | 0.44 | 14 | 22.9 | 3.54 | 9.49 | 24 | 4.32 | 0.42 | 18 |

| Tetherball | 89.0 | 132.99 | 167.70 | 24 | 5.04 | 0.63 | 18 | 22.9 | 3.6 | 13.82 | 23 | 4.24 | 0.41 | 20 |

| Expanding sphere | 95.1 | 128.80 | 159.51 | 25 | 5.09 | 0.42 | 12 | 22.9 | 7.51 | 21.12 | 22 | 4.2 | 0.41 | 21 |

SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study indicate that persons with dementia can indeed be effectively engaged by stimuli. Of those used in our study, the most engaging stimuli (based on engagement duration) were the one-on-one socializing, a real baby, both personalized self-identity stimuli, the respite video, and the lifelike doll. The stimuli refused most often included the plush animal, coloring with markers, robotic animal, childish-looking doll, and activity pillow, and all of these also received the lowest appropriateness rating.

Although we are cautious about generalizing to the entire population of persons with dementia, because dementia has a unique progression in each person, it appears that most persons with dementia can be engaged with some stimulus. In our sample, one-third had MMSE scores of 3 or lower and were nevertheless engaged with the stimuli for some period of time. We encountered participants who refused more often than not, but there was nonetheless always some stimulus that was able to engage them. There was no stimulus that was refused by 100% of the participants; all stimuli used in this study had someone who was engaged by them.

In general, less engaged participants showed higher engagement when the stimulus was real (e.g., a live pet) or when it was representative of real-world tasks (e.g., listening to music and reading a magazine). The most engaged participants generally responded best to social stimuli and the task-oriented activities.

We found that personal characteristics affect engagement. With regard to sex, both men and women had the most positive attitude toward a real baby. For women, the six stimuli with the highest rankings for duration included social stimuli, both real and simulated, along with stimuli based on self-identity; for men, the longest durations occurred with real social stimuli, self-identity stimuli, the large-print magazine, and stamping envelopes, a work-related task. As to stimulus categories, women showed more attention and had more positive attitudes toward both live and simulated social stimuli and toward artistic tasks. Attention was also comparatively higher for women for work-related stimuli. Cognitive functioning also played a role in engagement, as participants with comparatively higher levels of cognitive functioning were more likely to spend time engaged in work activities, whereas those with low levels of cognitive functioning were more engaged by simulated social stimuli (e.g., the respite video), which does not require active responses.

In terms of tailoring stimuli to specific individuals, personal characteristics such as sex and cognitive function should be taken into account. Cognitive function is of interest in that it increases engagement in general, but it also increases refusal (low stimulus acceptance). Stimulus acceptance appears to vary with social appropriateness of the stimulus. It is, therefore, imperative to consider the social appropriateness of the stimulus, especially for higher-functioning persons with dementia. Even more important is sensitivity to the person’s attitude toward social appropriateness. For example, a person who rejects a doll as childish is sending a message that he or she should be respected as an adult.

Manipulation of the stimuli was a function of the materials used and the ease of manipulation; i.e., the most manipulative stimuli were the fabric book, squeeze ball, and robotic animal. Therefore, the specific goal of stimulation needs to be stipulated when choosing a stimulus, i.e., is the goal to maximize positive attitude, duration, manipulation, another measure, or a combination of goals?

Based on our findings, it would behoove nursing homes to have some sort of socialization schedule in place, so that residents get the one-on-one interaction that appears to be so beneficial. In addition, staff should be trained to maximize socialization during activities of daily living performance (e.g., dressing, bathing, and feeding). Although one-to-one interaction and activities based on one’s self-identity were the most well received, these interventions can be challenging to deliver. In particular, they are more demanding of staff’s time, which can be especially difficult in understaffed establishments. Ways of incorporating these into current staff activities and ways of assisting staff members in preparing and delivering these stimuli need to be explored. Various stimuli should also be available to residents with dementia, such as easy work-related stimuli (e.g., stamping envelopes), a fabric book, music, and personalized stimuli.

Future research could examine the impact of other types of stimuli as well as study methods to maintain engagement beyond the short periods generally found in this study, such as which stimuli can be presented repeatedly, and for how many times, before they no longer elicit engagement. Previously, we found that although cognitively impaired residents with problematic behaviors benefited from repeated stimuli, those with relatively higher levels of cognitive function were more likely to register stimulus repetition, displaying responses such as boredom or increased complaining after only a few days.22,23 The research assistants conducting the trials had the impression that, with few exceptions, the washout period of 5 minutes was sufficient. The few who needed a longer washout usually remembered the trial even on the following day. However, future research could specifically study the impact of different washout periods and potential carryover effects. Overall, persons with dementia can indeed be engaged with stimuli and it is important to conduct these types of studies to continue to identify effective and safe treatments in response to the growing prevalence of dementia.24 Given the much lower levels of engagement in those with poorer cognitive function, it behooves future research to explore how stimuli can be modified and optimized with the progression of cognitive and functional decline associated with Alzheimer disease.8 Understanding the relationship among type of stimulus, cognitive function, and acceptance, attention, and attitude toward the stimuli can enable caregivers to maximize the desired benefit for persons with dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nursing home residents, their relatives, and the nursing homes’ staff members and administration for their help, without which this study would not have been possible.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AG R01 AG021497.

References

- 1.Kolanowski AM, Buettner L, Litaker M, et al. Factors that relate to activity engagement in nursing home residents. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:15–22. doi: 10.1177/153331750602100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutner NG, Brown PJ, Stavisky RC, et al. “Friendship” interactions and expression of agitation among residents of a dementia care unit. Res Aging. 2000;22:188–205. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolanowski AM, Buettner L, Costa PT, et al. Capturing interests: therapeutic recreation activities for persons with dementia. Ther Recreation J. 2001;35:220–235. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buettner LL, Fitzsimmons S, Atav AS. Predicting outcomes of therapeutic recreation interventions for older adults with dementia and behavioral symptoms. Ther Recreation J. 2006;40:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Management of verbally disruptive behaviors in the nursing home. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M369–M377. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.6.m369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serby MJ, Roane DM, Lantz MS, et al. Current attitudes regarding treatment of agitation and psychosis in dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:174. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818cd38f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos C, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:561–573. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buettner LL. Simple pleasures: a multi-level sensorimotor intervention for nursing home residents with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1999;14:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson NM. Short takes on long-term care: simple pleasures: a new intervention transforms one long-term care facility. Am J Nurs. 2005;105:54–55. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200507000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valanzuela M, Sachdev P. Brain reserve and dementia: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:451–454. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valanzuela M, Sachdev P. Can cognitive exercise prevent the onset of dementia? Systematic review of randomized clinical trials with longitudinal follow-up. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:179–187. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181953b57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallacher J, Bayer A, Ben-Shlomo Y. Commentary: activity each day keeps dementia away—does social interaction really preserve cognitive function? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:872–873. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris J, Hawes C, Murphy K, et al. MDS Resident Assessment. Natick MA: Eliot Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen-Mansfield J, Golander H, Arnheim G. Self-identity in older persons suffering from dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:381–394. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H. Utilization of self-identity roles for designing interventions for persons with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:P202–P212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen-Mansfield J, Dakheel-Ali M, Marx MS. Engagement in persons with dementia: the concept and its measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:299–307. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818f3a52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen-Mansfield J, Kerin P, Pawlson LG, et al. Informed consent for research in the nursing home: processes and results. Gerontologist. 1988;28:355–359. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall L, Hare J. Video respite™ for cognitively impaired persons in nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1997;12:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lund DA, Hill RD, Caserta MS, et al. Video respite™: an innovative resource for family, professional caregivers, and persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 1995;35:683–687. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, Fisher J. Characterization of family-generated videotapes for the management of verbally disruptive behaviors. J Appl Gerontol. 2000;19:42–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P. Environmental influences on agitation: an integrative summary of an observational study. Am J Alzheimers Care Relat Dis Res. 1995;10:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavretsky H. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease and related disorders: why do treatments work in clinical practice but not in the randomized trials? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:523–527. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318178416c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]